Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

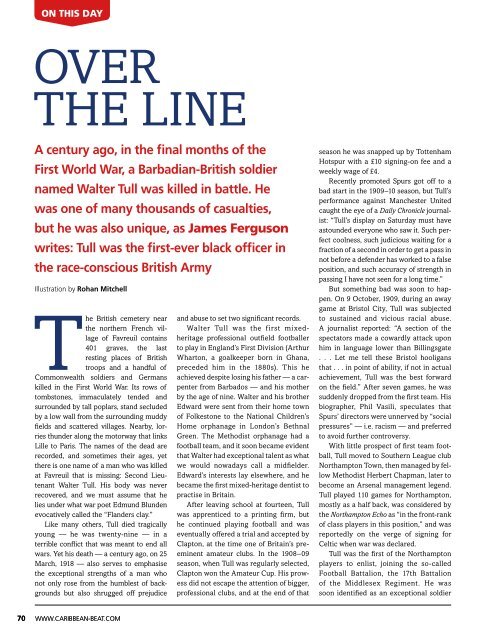

on this day<br />

Over<br />

the line<br />

A century ago, in the final months of the<br />

First World War, a Barbadian-British soldier<br />

named Walter Tull was killed in battle. He<br />

was one of many thousands of casualties,<br />

but he was also unique, as James Ferguson<br />

writes: Tull was the first-ever black officer in<br />

the race-conscious British Army<br />

Illustration by Rohan Mitchell<br />

The British cemetery near<br />

the northern French village<br />

of Favreuil contains<br />

401 graves, the last<br />

resting places of British<br />

troops and a handful of<br />

Commonwealth soldiers and Germans<br />

killed in the First World War. Its rows of<br />

tombstones, immaculately tended and<br />

surrounded by tall poplars, stand secluded<br />

by a low wall from the surrounding muddy<br />

fields and scattered villages. Nearby, lorries<br />

thunder along the motorway that links<br />

Lille to Paris. The names of the dead are<br />

recorded, and sometimes their ages, yet<br />

there is one name of a man who was killed<br />

at Favreuil that is missing: Second Lieutenant<br />

Walter Tull. His body was never<br />

recovered, and we must assume that he<br />

lies under what war poet Edmund Blunden<br />

evocatively called the “Flanders clay.”<br />

Like many others, Tull died tragically<br />

young <strong>—</strong> he was twenty-nine <strong>—</strong> in a<br />

terrible conflict that was meant to end all<br />

wars. Yet his death <strong>—</strong> a century ago, on 25<br />

<strong>March</strong>, 1918 <strong>—</strong> also serves to emphasise<br />

the exceptional strengths of a man who<br />

not only rose from the humblest of backgrounds<br />

but also shrugged off prejudice<br />

and abuse to set two significant records.<br />

Walter Tull was the first mixedheritage<br />

professional outfield footballer<br />

to play in England’s First Division (Arthur<br />

Wharton, a goalkeeper born in Ghana,<br />

preceded him in the 1880s). This he<br />

achieved despite losing his father <strong>—</strong> a carpenter<br />

from Barbados <strong>—</strong> and his mother<br />

by the age of nine. Walter and his brother<br />

Edward were sent from their home town<br />

of Folkestone to the National Children’s<br />

Home orphanage in London’s Bethnal<br />

Green. The Methodist orphanage had a<br />

football team, and it soon became evident<br />

that Walter had exceptional talent as what<br />

we would nowadays call a midfielder.<br />

Edward’s interests lay elsewhere, and he<br />

became the first mixed-heritage dentist to<br />

practise in Britain.<br />

After leaving school at fourteen, Tull<br />

was apprenticed to a printing firm, but<br />

he continued playing football and was<br />

eventually offered a trial and accepted by<br />

Clapton, at the time one of Britain’s preeminent<br />

amateur clubs. In the 1908–09<br />

season, when Tull was regularly selected,<br />

Clapton won the Amateur Cup. His prowess<br />

did not escape the attention of bigger,<br />

professional clubs, and at the end of that<br />

season he was snapped up by Tottenham<br />

Hotspur with a £10 signing-on fee and a<br />

weekly wage of £4.<br />

Recently promoted Spurs got off to a<br />

bad start in the 1909–10 season, but Tull’s<br />

performance against Manchester United<br />

caught the eye of a Daily Chronicle journalist:<br />

“Tull’s display on Saturday must have<br />

astounded everyone who saw it. Such perfect<br />

coolness, such judicious waiting for a<br />

fraction of a second in order to get a pass in<br />

not before a defender has worked to a false<br />

position, and such accuracy of strength in<br />

passing I have not seen for a long time.”<br />

But something bad was soon to happen.<br />

On 9 October, 1909, during an away<br />

game at Bristol City, Tull was subjected<br />

to sustained and vicious racial abuse.<br />

A journalist reported: “A section of the<br />

spectators made a cowardly attack upon<br />

him in language lower than Billingsgate<br />

. . . Let me tell these Bristol hooligans<br />

that . . . in point of ability, if not in actual<br />

achievement, Tull was the best forward<br />

on the field.” After seven games, he was<br />

suddenly dropped from the first team. His<br />

biographer, Phil Vasili, speculates that<br />

Spurs’ directors were unnerved by “social<br />

pressures” <strong>—</strong> i.e. racism <strong>—</strong> and preferred<br />

to avoid further controversy.<br />

With little prospect of first team football,<br />

Tull moved to Southern League club<br />

Northampton Town, then managed by fellow<br />

Methodist Herbert Chapman, later to<br />

become an Arsenal management legend.<br />

Tull played 110 games for Northampton,<br />

mostly as a half back, was considered by<br />

the Northampton Echo as “in the front-rank<br />

of class players in this position,” and was<br />

reportedly on the verge of signing for<br />

Celtic when war was declared.<br />

Tull was the first of the Northampton<br />

players to enlist, joining the so-called<br />

Football Battalion, the 17th Battalion<br />

of the Middlesex Regiment. He was<br />

soon identified as an exceptional soldier<br />

70 WWW.CARIBBEAN-BEAT.COM