BusinessDay 22 Mar 2018

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

24 BUSINESS DAY Thursday <strong>22</strong> <strong>Mar</strong>ch <strong>2018</strong><br />

Harvard<br />

Business<br />

Review<br />

Global Business Perspectives<br />

CONNECTING THE WORLD ONE BUSINESS AT A TIME<br />

Dispute resolution for India and Bangladesh<br />

KATIE SHONK<br />

Sometimes in international<br />

negotiations,<br />

disputes are<br />

left to fester for<br />

years until parties<br />

decide there is something<br />

to be gained from reaching<br />

a dispute resolution. In an<br />

example of a cross-cultural<br />

negotiation case study, the<br />

nations of Bangladesh and<br />

India seized an opportunity<br />

to push the restart button<br />

on their bumpy relationship<br />

by resolving one such<br />

ongoing international conflict.<br />

LIVING IN NO MAN’S<br />

LAND<br />

For decades, small plots<br />

of land belonging to India<br />

and Bangladesh were completely<br />

surrounded by the<br />

other nation’s territory on<br />

each side of the twisting<br />

4,000-kilometer border between<br />

the two countries.<br />

The origins of these socalled<br />

enclaves — 111 Bangladeshi,<br />

51 Indian — were<br />

obscure. The dots of land,<br />

just 15 square miles in total,<br />

may have been bargaining<br />

chips in a 1711 international<br />

negotiation in the region,<br />

according to The Economist<br />

magazine.<br />

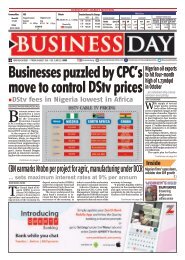

Villagers in Nalcity, Bangladesh, are pictured through the window of a Bangladeshi military helicopter as they greet<br />

the arrival of relief supplies from the U.S. on Nov. 23, 2007. The impact of cyclone Sidr on Bangladesh can be compared<br />

to a “mini-tsunami” and there is a continued urgent need for international aid, the United Nations humanitarian<br />

affairs office said Friday. (CREDIT: Ruth Fremson/The New York Times)<br />

Isolated from their home<br />

countries, the enclaves had<br />

long been neglected. With<br />

neither India nor Bangladesh<br />

allowing the other to<br />

administer the enclaves,<br />

residents were trapped<br />

without hospitals, schools,<br />

courts or travel privileges<br />

in the nation that surrounded<br />

them.<br />

In the 1970s, the Indian<br />

and newly formed Bangladeshi<br />

governments agreed<br />

to swap their territories,<br />

such that each would acquire<br />

the enclaves within its<br />

borders. India said it would<br />

forgo compensation for<br />

an approximate net loss of<br />

about 10,000 acres. Those<br />

living in the enclaves could<br />

decide whether to move to<br />

their homeland to remain<br />

its citizens or stay put and<br />

become nationals of their<br />

new country, according<br />

to Reuters. However, the<br />

international negotiation<br />

proved unpopular and remained<br />

unratified for decades.<br />

DUSTING OFF AN OLD<br />

DISPUTE — RESOLUTION<br />

FOR AN OLD DEAL<br />

That changed in 2015,<br />

when the prime ministers<br />

of both countries recognized<br />

that resolving the international<br />

conflict would<br />

benefit not only the enclaves’<br />

residents but also<br />

them personally. Indian<br />

Prime Minister Narendra<br />

Modi sought to deflect<br />

attention from domestic<br />

setbacks with the landswap<br />

agreement. And Bangladeshi<br />

Prime Minister<br />

Sheikh Hasina, who had<br />

been widely criticized for<br />

authorizing violent crackdowns<br />

against her political<br />

opposition, saw an opportunity<br />

to demonstrate<br />

her legitimacy through an<br />

international negotiation<br />

with the world’s largest democracy,<br />

according to the<br />

Observer.<br />

During a brief visit<br />

to Bangladesh’s capital,<br />

Dhaka, Modi oversaw<br />

the signing of about 20<br />

agreements with India’s<br />

neighbor, including the<br />

land-swap deal. Simultaneously,<br />

Indian conglomer-<br />

ates signed draft contracts<br />

to invest about $5 billion<br />

in improving Bangladesh’s<br />

aging power sector.<br />

Those who had been<br />

stranded in the enclaves,<br />

many for their entire lives,<br />

expressed relief that their<br />

fate had been finally settled.<br />

Most decided to stay<br />

put, accept a change in<br />

citizenship, and await the<br />

arrival of infrastructure and<br />

administration. “We didn’t<br />

have hospitals, schools,<br />

electricity — nothing,”<br />

Madhusudan Mohanto, a<br />

resident of an enclave in<br />

Bangladesh, told The Wall<br />

Street Journal. “Now we<br />

hope we’ll get our rights<br />

back.”<br />

Indian officials said the<br />

enclave agreement signaled<br />

that their nation was<br />

equipped to tackle more<br />

difficult border disputes<br />

with China and Pakistan.<br />

The deal also allowed India,<br />

long perceived by Bangladeshi<br />

leaders and citizens<br />

as overbearing on territorial<br />

and migration issues,<br />

to build trust and goodwill<br />

as it prepared to wrap up a<br />

more difficult dispute with<br />

Bangladesh about rights<br />

to the waters of the Teesta<br />

River, which flows through<br />

both countries.<br />

(Katie Shonk is the editor of the<br />

Program on Negotiation at Harvard<br />

Law School.)<br />

2017 Harvard Business School Publishing Corp. Distributed by The New York Times Syndicate