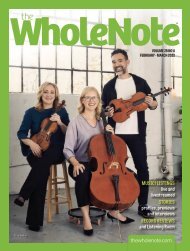

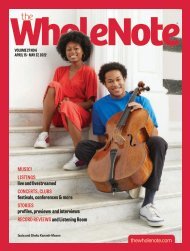

Volume 23 Issue 7 - April 2018

In this issue: we talk with jazz pianist Thompson Egbo-Egbo about growing up in Toronto, building a musical career, and being adaptive to change; pianist Eve Egoyan prepares for her upcoming Luminato project and for the next stage in her long-term collaborative relationship with Spanish-German composer Maria de Alvear; jazz violinist Aline Homzy, halfway through preparing for a concert featuring standout women bandleaders, talks about social equity in the world of improvised music; and the local choral community celebrates the life and work of choral conductor Elmer Iseler, 20 years after his passing.

In this issue: we talk with jazz pianist Thompson Egbo-Egbo about growing up in Toronto, building a musical career, and being adaptive to change; pianist Eve Egoyan prepares for her upcoming Luminato project and for the next stage in her long-term collaborative relationship with Spanish-German composer Maria de Alvear; jazz violinist Aline Homzy, halfway through preparing for a concert featuring standout women bandleaders, talks about social equity in the world of improvised music; and the local choral community celebrates the life and work of choral conductor Elmer Iseler, 20 years after his passing.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

where so much of what happens onstage is guided by performers’<br />

offstage social relationships. In a 2013 article for NewMusicBox, Ellen<br />

McSweeney talks about how women performers often pay a hidden<br />

“likability tax” when they come off as too self-promoting, assertive,<br />

or success-oriented. And in an ensemble situation, where performers<br />

rely on having both a supportive fan base and a network of collaborators<br />

to survive, being seen as unlikable can carry a high cost.<br />

“I’m doing ‘bitch’ in quotations right now, because I understand<br />

it’s a swear word as well,” says Homzy when she explains the project.<br />

“But for us, it’s reclaiming that word – especially as a woman leader,<br />

when women often get called that name for being too bossy.”<br />

It’s a mentality that impacts how women musicians operate within<br />

jazz culture – and one that extends to the way that they perform. In his<br />

book Swingin’ the Dream, Lewis Erenberg writes about how during<br />

the 1940s, women musicians were<br />

often seen as temporary, annoying<br />

replacements for the men who<br />

went to war – and that the<br />

prevailing opinion was that they<br />

should either act like “good girls”<br />

or “play like men.” Seventy-five<br />

years later, Homzy still encounters<br />

that attitude in the field.<br />

“I think one reason why a lot<br />

of women don’t show up to jam<br />

sessions is because you feel like<br />

you really have to prove yourself,”<br />

she says. “Everyone feels intimidated<br />

by that situation, but as a<br />

woman, it’s like – doubly that.<br />

And some people – some guys –<br />

will see a woman come in and<br />

on purpose count in the hardest<br />

tune, really fast, because they<br />

want to see you fail. It’s really<br />

discouraging to witness.<br />

“It becomes about [whether]<br />

you’re able to, we say, ‘Hang with<br />

the guys,’” she continues. “If you<br />

can ‘keep up’ then it’s like you’re<br />

considered ‘ok’ in the guys’ books.<br />

I think that some women take that<br />

position: ‘I’m like one of the guys.’<br />

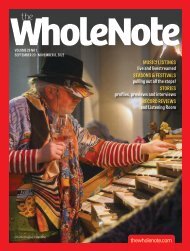

Clockwise from top left: Aline<br />

Homzy (violin), Emma Smith (bass),<br />

Anh Phung (flute), and Magdelys<br />

Savigne (drums/percussion)<br />

And I think it’s really dangerous. I’ve been in that situation too, where<br />

I’ve been like ‘I feel like the guys are accepting me.’ You soon realize<br />

that there are sometimes ulterior motives for that, which are quite<br />

disturbing.”<br />

Homzy says that it’s a particularly big problem for younger women<br />

artists who are early-career or still in school, because it can make it<br />

difficult for them to realize their worth. “It took a lot of work for me<br />

to realize that wanting to be in the ‘boys club’ was a really toxic way to<br />

think about myself,” she says. “I feel like it’s hard to know how good<br />

you are, when you first come out of school. As a female instrumentalist,<br />

you’re always told, ‘Play more like this,’ or relating to my instrument,<br />

‘Play more like a saxophone, play more like a horn.’ [I had to]<br />

come out of school and realize, no – that’s not what I’m doing. I’m a<br />

violinist, this is my sound and this is my style.<br />

“You [begin to] realize that sometimes you’re maybe even better<br />

than some of your male colleagues – which is interesting, because a<br />

lot of male colleagues tend to think that they’re better than you,” she<br />

adds. “And it can be really uncomfortable, because [those colleagues]<br />

really want to take over – in conversations, and in music.”<br />

Being heard<br />

For Homzy, that gendered feeling of being unheard has particular<br />

amplifications within the jazz world as a whole. It’s a big part of why<br />

she chose the Canadian Music Centre – a space not often seen as a jazz<br />

venue, and a first for the TD Toronto Jazz Festival – for this show.<br />

“Part of the reason that I applied for this project was that I wanted it<br />

to be at a venue that wasn’t just a bar or a club,” she explains. “I wanted<br />

it to be in a ‘listening room,’ where people listen and don’t talk – where<br />

we’re all there to listen to the music. All four of us write original music<br />

and we all consider ourselves artists. I wanted to provide a place to play<br />

where people are going to listen, as opposed to talking over you.”<br />

I ask if there are many spaces in Toronto like that for jazz; she says<br />

there aren’t.<br />

She mentions that she came to the violin from a classical background,<br />

and that the feeling of being undervalued as an artist is a<br />

chronic issue in the non-classical world. From her perspective, the<br />

difference is night and day.<br />

“We’re just not taken as seriously,” she says. “You see it with the way<br />

we get paid. You see it with how people think it’s ok to talk over what<br />

you’re doing [at any point]. I want to bridge that gap, and show people<br />

that improvised music can be – and is – really awesome.”<br />

‘Women’s music’<br />

In December, The New York Times published an article claiming<br />

that 2017 was a “year of reckoning”<br />

for women in jazz – a time when we<br />

saw a number of standout women<br />

instrumentalists presenting projects<br />

that were bold, musically inventive,<br />

and squarely their own. It’s an idea<br />

that shouldn’t be that shocking –<br />

but Homzy talks about how even<br />

today, people seem to have a hard<br />

time coming around to the idea of<br />

women authorship in music.<br />

“The info about this project is<br />

all there. But so many people have<br />

seen it and asked me, ‘Wow, so<br />

are you playing the whole Bitches<br />

Brew Miles Davis album?’” she<br />

laughs. “It’s funny, but also kind of<br />

disappointing in some way. Because<br />

they completely missed the point.”<br />

Still, Homzy is dedicated to lifting<br />

up the work of women creators. Not<br />

because there’s anything inherently<br />

distinctive about their music – far<br />

from it – but because there’s a lot<br />

of valid experience and perspective<br />

there. And when our music doesn’t<br />

represent the demographics of our communities, that perspective,<br />

and the power and beauty that go along with it, is something we<br />

miss out on.<br />

“I realized, after so many years: I’d been doing these things, playing<br />

or writing-wise – not specifically because I wanted to please other<br />

musicians, but because I’d been influenced by that [oppression],”<br />

she says. “And now, I’m writing music in a way that is influenced by<br />

those experiences. We’ve experienced different challenges; I think that<br />

makes a lot of women’s music sound unique and different.”<br />

That 2017 New York Times article references the same thing.<br />

“There’s nothing to suggest that these...musicians expressed themselves<br />

in any particular way because of their gender,” it reads, “but<br />

what we know is that until recently they might not have been in a<br />

position to stand up onstage alone, addressing the audience with<br />

generosity and informality, empowering the room.” As Homzy seems<br />

to attest, that’s its own rare and powerful thing – and an experience<br />

that, without question, is worth seeking.<br />

“The Smith Sessions presents: Bitches Brew,” featuring Aline<br />

Homzy, Emma Smith, Anh Phung and Magdelys Sevigne,<br />

will be presented on <strong>April</strong> 28 at the Canadian Music Centre’s<br />

Chalmers House in Toronto, as part of the <strong>2018</strong> TD Toronto Jazz<br />

Festival Discovery Series. The event will also be livestreamed<br />

by the Canadian Music Centre, at https://livestream.com/<br />

accounts/13330169/events/8050734.<br />

Sara Constant is a flutist and music writer based in Toronto,<br />

and is digital media editor at The WholeNote.<br />

She can be reached at editorial@thewholenote.com.<br />

18 | <strong>April</strong> <strong>2018</strong> thewholenote.com