26_1-8

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

6<br />

No.<strong>26</strong> APRIL 24, 2018<br />

CULT URE<br />

WWW.DAY.KIEV.UA<br />

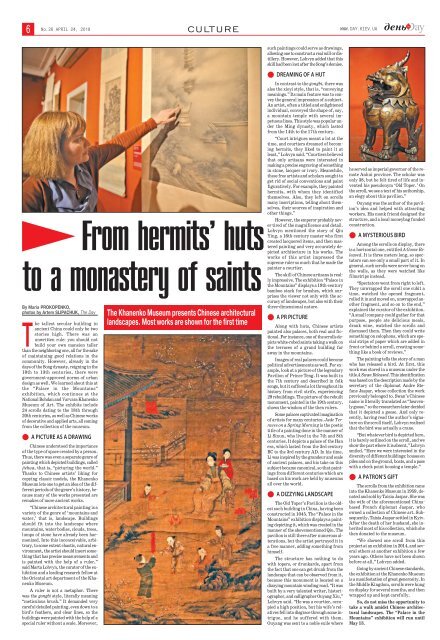

From hermits’ huts<br />

to a monastery of saints<br />

By Maria PROKOPENKO,<br />

photos by Artem SLIPACHUK, The Day<br />

The tallest secular building in<br />

ancient China could only be two<br />

stories high. There was an<br />

unwritten rule: you should not<br />

build your own mansion taller<br />

than the neighboring one, all for the sake<br />

of maintaining good relations in the<br />

community. However, already in the<br />

days of the Song dynasty, reigning in the<br />

10th to 13th centuries, there were<br />

government-approved norms of urban<br />

design as well. We learned about this at<br />

the “Palace in the Mountains”<br />

exhibition, which continues at the<br />

National Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko<br />

Museum of Art. The exhibits include<br />

24 scrolls dating to the 18th through<br />

20th centuries, as well as Chinese works<br />

of decorative and applied arts, all coming<br />

from the collection of the museum.<br />

● A PICTURE AS A DRAWING<br />

Chinese understood the importance<br />

of the type of space created by a person.<br />

Thus, there was even a separate genre of<br />

painting which depicted buildings, called<br />

jiehua, that is, “picturing the world.”<br />

Thanks to Chinese artists’ liking for<br />

copying classic models, the Khanenko<br />

Museum lets one to get an idea of the different<br />

periods of the genre’s history, because<br />

many of the works presented are<br />

remakes of more ancient works.<br />

“Chinese architectural painting is a<br />

variety of the genre of ‘mountains and<br />

water,’ that is, landscape. Buildings<br />

should fit into the landscape where<br />

mountains, water bodies, clouds, trees,<br />

lumps of stone have already been harmonized.<br />

Into this inconceivable, arbitrary,<br />

to some extent chaotic, natural environment,<br />

the artist should insert something<br />

that has precise measurements and<br />

is painted with the help of a ruler,”<br />

said Marta Lohvyn, the curator of the exhibition<br />

and a leading research fellow at<br />

the Oriental art department of the Khanenko<br />

Museum.<br />

A ruler is not a metaphor. There<br />

was the gongbi style, literally meaning<br />

“meticulous brush.” It demanded very<br />

careful detailed painting, even down to a<br />

bird’s feathers, and clear lines, so the<br />

buildings were painted with the help of a<br />

special ruler without a scale. Moreover,<br />

The Khanenko Museum presents Chinese architectural<br />

landscapes. Most works are shown for the first time<br />

such paintings could serve as drawings,<br />

allowing one to constructareal mill or distillery.<br />

However, Lohvyn added that this<br />

skill had been lost after the Song’s demise.<br />

● DREAMING OF A HUT<br />

In contrast to the gongbi, there was<br />

also the xieyi style, that is, “conveying<br />

meanings.” Its main feature was to convey<br />

the general impression of a subject.<br />

An artist, often a titled and enlightened<br />

individual, conveyed the shape of, say,<br />

a mountain temple with several impetuous<br />

lines. This style was popular under<br />

the Ming dynasty, which lasted<br />

from the 14th to the 17th century.<br />

“Court intrigues meant a lot at the<br />

time, and courtiers dreamed of becoming<br />

hermits, they liked to paint it at<br />

least,” Lohvyn said. “Courtiers believed<br />

that only artisans were interested in<br />

making a precise engraving of something<br />

in stone, lacquer or ivory. Meanwhile,<br />

these free artists and scholars sought to<br />

get rid of social conventions and paint<br />

figuratively. For example, they painted<br />

hermits, with whom they identified<br />

themselves. Also, they left on scrolls<br />

many inscriptions, telling about themselves,<br />

their sources of inspiration and<br />

other things.”<br />

However, the emperor probably never<br />

tired of the magnificence and detail.<br />

Lohvyn mentioned the story of Qiu<br />

Ying, a 16th-century master who first<br />

created lacquered items, and then mastered<br />

painting and very accurately depicted<br />

architecture in his works. The<br />

works of this artist impressed the<br />

supreme ruler so much that he made the<br />

painter a courtier.<br />

The skill of Chinese artisans is really<br />

impressive. The exhibition “Palace in<br />

the Mountains” displays a 19th-century<br />

bamboo stack for brushes, which surprises<br />

the viewer not only with the accuracy<br />

of landscapes, but also with their<br />

three-dimensional nature.<br />

● A PR PICTURE<br />

Along with huts, Chinese artists<br />

painted also palaces, both real and fictional.<br />

For instance, one of the scrolls depicts<br />

white-robed saints taking a walk on<br />

the terraces of a grand building far<br />

away in the mountains.<br />

Images of real palaces could become<br />

political advertisements as well. For example,<br />

look at a picture of the legendary<br />

Pavilion of Prince Teng. It was built in<br />

the 7th century and described in folk<br />

songs, but it suffered a lot throughout its<br />

history from civil strife, experiencing<br />

29 rebuildings. The picture of the rebuilt<br />

monument, painted in the 19th century,<br />

shows the wisdom of the then rulers.<br />

Some palaces captivated imagination<br />

of artists for many centuries. Jade Terraces<br />

on a Spring Morning is the poetic<br />

title of a painting done in the manner of<br />

Li Sixun, who lived in the 7th and 8th<br />

centuries. It depicts a palace of the Han<br />

era, which lasted from the 3rd century<br />

BC to the 3rd century AD. In his time,<br />

Li was inspired by the grandeur and scale<br />

of ancient palaces, and his take on this<br />

subject became canonical, so that paintings<br />

from different centuries which are<br />

based on his work are held by museums<br />

all over the world.<br />

● A DIZZYING LANDSCAPE<br />

The Old Toper’s Pavilion is the oldest<br />

such building in China, having been<br />

constructed in 1045. The “Palace in the<br />

Mountains” exhibition displays a painting<br />

depicting it, which was created in the<br />

manner of the abovementioned Qiu. The<br />

pavilion is still there after numerous alterations,<br />

but the artist portrayed it in<br />

a free manner, adding something from<br />

himself.<br />

The structure has nothing to do<br />

with topers, or drunkards, apart from<br />

the fact that one can get drunk from the<br />

landscape that can be observed from it,<br />

because this monument is located on a<br />

dizzying mountain winding road. “It was<br />

built by a very talented writer, historiographer,<br />

and calligrapher Ouyang Xiu,”<br />

Lohvyn said. “He was a courtier, occupied<br />

a high position, but his wife’s relatives<br />

fell into disgrace through some intrigue,<br />

and he suffered with them.<br />

Ouyang was sent to a noble exile where<br />

he served as imperial governor of the remote<br />

Anhui province. The scholar was<br />

only 38, but he felt tired of life and invented<br />

his pseudonym ‘Old Toper.’ On<br />

the scroll, we see a text of his authorship,<br />

an elegy about this pavilion.”<br />

Ouyang was the author of the pavilion’s<br />

idea and helped with attracting<br />

workers. His monk friend designed the<br />

structure, and a local moneybag funded<br />

construction.<br />

● A MYSTERIOUS BIRD<br />

Among the scrolls on display, there<br />

is a horizontal one, entitled A Goose Released.<br />

It is three meters long, so spectators<br />

can see only a small part of it. In<br />

general, such scrolls were never hung on<br />

the walls, as they were watched like<br />

filmstrips instead.<br />

“Spectators went from right to left.<br />

They unwrapped the scroll one cubit a<br />

time, watched the opened fragment,<br />

rolled it in and moved on, unwrapped another<br />

fragment, and so on to the end,”<br />

explained the curator of the exhibition.<br />

“A small company could gather for that<br />

purpose, people ate delicious meals,<br />

drank wine, watched the scrolls and<br />

discussed them. Then they could write<br />

something on colophons, which are special<br />

strips of paper which are added in<br />

front or behind a scroll, creating something<br />

like a book of reviews.”<br />

The painting tells the story of a man<br />

who has released a bird. At first, this<br />

work was stored in a museum under the<br />

title A Swan Released. This identification<br />

was based on the description made by the<br />

secretary of the diplomat Andre Stefane<br />

Jaspar, whose collection the work<br />

previously belonged to. Swan’s Chinese<br />

name is literally translated as “heavenly<br />

goose,” so the researchers later decided<br />

that it depicted a goose. And only recently,<br />

having read the author’s signature<br />

on the scroll itself, Lohvyn realized<br />

that the bird was actually a crane.<br />

“But whatever bird is depicted here,<br />

it is barely outlined on the scroll, and we<br />

show the part where it is absent,” Lohvyn<br />

smiled. “Here we were interested in the<br />

diversity of different buildings: houses on<br />

piles and on the ground, boats, and a pass<br />

with a check point housing a temple.”<br />

● A PATRON’S GIFT<br />

The scrolls from the exhibition came<br />

into the Khanenko Museum in 1959, donated<br />

and sold by Taisia Jaspar. She was<br />

the wife of the aforementioned Chinabased<br />

French diplomat Jaspar, who<br />

owned a collection of Chinese art. Subsequently,<br />

Taisia Jaspar settled in Kyiv.<br />

After the death of her husband, she inherited<br />

most of his collection, which she<br />

then donated to the museum.<br />

“We showed one scroll from this<br />

project at an exhibition in 2014, and several<br />

others at another exhibition a few<br />

years ago. Others have not been shown<br />

before at all,” Lohvyn added.<br />

Going by ancient Chinese standards,<br />

the exhibition at the Khanenko Museum<br />

is a manifestation of great generosity. In<br />

the Middle Kingdom, scrolls were hung<br />

on display for several months, and then<br />

wrapped up and kept carefully.<br />

So, do not miss the opportunity to<br />

take a walk amidst Chinese architectural<br />

landscapes. The “Palace in the<br />

Mountains” exhibition will run until<br />

May 13.