3. - Schlösser-Magazin

3. - Schlösser-Magazin

3. - Schlösser-Magazin

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

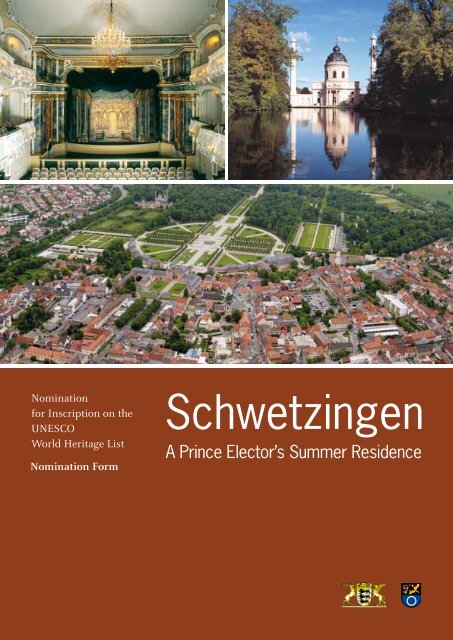

Nomination<br />

for Inscription on the<br />

UNESCO<br />

World Heritage List<br />

Nomination Form<br />

Schwetzingen<br />

A Prince Elector’s Summer Residence

Nomination<br />

for Inscription on the<br />

UNESCO<br />

World Heritage List<br />

Nomination Form<br />

Schwetzingen<br />

A Prince Elector’s Summer Residence

Contents<br />

Nomination Form<br />

1. Identification of the Property 7<br />

2. Description 11<br />

<strong>3.</strong> Justification for Inscription 33<br />

4. State of Conservation and Factors Affecting the Property 117<br />

5. Protection and Management of the Property 125<br />

6. Monitoring 149<br />

7. Documentation 157<br />

8. Contact Information 161<br />

9. Signatures on Behalf of the State Party 165<br />

Statements on the Nomination<br />

I. Report on the Architectural and Art Historical Importance: Prof. Dr. Michael Hesse 167<br />

II. Report on the Historical Importance of the Garden: Prof. Dr. Géza Hajós 185<br />

III. Report on the Excellence of Garden Conservation in Schwetzingen:<br />

Dr. Klaus von Krosigk 194<br />

IV. Report on the Historical Importance: Dr. Kurt Andermann 200<br />

V. Report on the Music Historical Importance: Dr. Bärbel Pelker 209<br />

VI. Interpretation of the Palace Gardens as a whole: Dr. Michael Niedermeier 233<br />

About the Experts 265<br />

Imprint, Photo Credits 268

ARION FOUNTAIN<br />

Prof. Dr. Géza Hajós<br />

„ “<br />

… nowhere in the world is it possible to experience the confrontation of the two attitudes<br />

towards Nature as directly and immediately as at Schwetzingen. The Trianon at Versailles<br />

may offer a similar situation, but the Baroque gardens of Louis XIV and Marie<br />

Antoinette’s landscape park are not immediately adjacent to each other, and artistically<br />

less in tune with each other than the Baroque garden created by Petri and Pigage and the<br />

landscape garden added by Sckell – for which Pigage continued to create buildings.

1. Identification of the Property<br />

1.a)<br />

Country<br />

Federal Republic of Germany<br />

1.b)<br />

State, Province or Region<br />

State of Baden-Württemberg, Karlsruhe<br />

Administrative Region, European<br />

Metropolitan Region Rhine-Neckar<br />

Federal Republic of Germany<br />

Schwetzingen<br />

Baden-<br />

Württemberg<br />

Topographical location of<br />

Schwetzingen.<br />

1.<br />

7

1. 1.c)<br />

8<br />

1. Identification of the Property<br />

Name of Property<br />

Schwetzingen: A Prince Elector’s Summer<br />

Residence<br />

1.d)<br />

Geographical Coordinates to the<br />

Nearest Second<br />

Approx. centre of property (centre of Arion<br />

fountain in palace gardens):<br />

North: 49°23’01’’<br />

East: 8°34’05’’<br />

1.e)<br />

Maps and Plans Showing the<br />

Boundaries of the Nominated<br />

Property and Buffer Zone<br />

Map 1 shows the precise delineation of the<br />

boundaries of the property nominated for<br />

inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage<br />

List, along with the boundaries of the<br />

surrounding buffer zone.<br />

The delineation of the property reflects the<br />

integral chararacter of the palace buildings,<br />

palace grounds, and Baroque town centre with<br />

its historic lines of sight. The property begins<br />

in the east with the original Baroque axis,<br />

taking in the road and the nineteenth-century<br />

buildings lining it, which give way to Baroque<br />

buildings on each side. Following this comes<br />

the Schlossplatz (palace square) aligned<br />

along the same axis, including the Baroque<br />

buildings along the square. The palace<br />

and gardens are delimited by boundaries<br />

unchanged for over two hundred years, and<br />

the property continues along these bounds,<br />

with the exception of an arm extending out<br />

to the north along the road marking the<br />

transverse axis.<br />

The buffer zone encompasses the historic foci<br />

of settlement which flank the main axis in the<br />

east. It surrounds the nominated property so<br />

as to preserve the historic views of and from<br />

the palace gardens; this applies particularly to<br />

the view out over the open countryside to the<br />

west of the gardens. In the south the buffer<br />

zone includes the historic hunting park with<br />

its star-shaped arrangement of avenues, part<br />

of the Baroque cultural landscape created<br />

in Elector Carl Theodor’s time. Monument<br />

protection legislation rules out any alterations<br />

which would adversely affect the gardens,<br />

both inside and outside the buffer zone.<br />

1.f)<br />

Area of Nominated Property (ha.)<br />

and Proposed Buffer Zone (ha.)<br />

Area of property: 78,23 ha<br />

Area of buffer zone: 471,54 ha

1. Identification of the Property<br />

1.<br />

Map 1, Boundaries of the<br />

nominated property (red) and<br />

the buffer zone (green).<br />

9

1.<br />

10<br />

1. Identification of the Property<br />

TEMPLE OF APOLLO<br />

Prof. Dr. Michael Hesse<br />

„… among the most original architectural creations at Schwetzingen is the Apollo precinct with<br />

the temple (from 1765/66) which belongs to two different spheres. From the terraced basement<br />

facing the canal in the west the visitor must accomplish a quasi-ritualistic ascent through dark<br />

tunnels lined with rough stone – as it were, through the sphere of the narrow, obscure, unfinished –<br />

towards the sunlit upper platform with its ideal, Classical monopteros sheltering the god of order,<br />

clarity and reason. At the same time and viewed from the other side, that is to say from the green<br />

theatre, the temple surmounts the stage. Here Apollo is the god of the arts, leader of the muses<br />

on Mount Helicon, where the hoof of Pegasus had called forth the well of Hippocrene. Its sacred<br />

waters are represented at Schwetzingen by a small waterfall offered to humanity by two naiads.

2. Description<br />

2.a)<br />

Description of the Property<br />

Geographical Position<br />

Schwetzingen is located in the north west of<br />

the state of Baden-Württemberg, on the lower<br />

terrace of the Rhine plain, approx. 18km<br />

southeast of Mannheim and 12km west of<br />

Heidelberg. To the north of Schwetzingen<br />

is the alluvial fan of the Neckar, which<br />

flows from Heidelberg to join the Rhine<br />

by Mannheim; to the west is the Rhine<br />

flood plain, and there are extensive areas<br />

of forest to the south. The historic lines of<br />

communication of the Rhine itself and the<br />

Bergstrasse, an old German trade route, along<br />

with the contemporary Karlsruhe-Frankfurt<br />

Neustadt<br />

Kalmit<br />

railway and the A5 and A6 motorways bear<br />

testament to the importance of the Rhine<br />

valley as a connection between north and<br />

south.<br />

Schwetzingen`s ease of access made it an<br />

obvious focus of industrialisation in the<br />

nineteenth and twentieth-centuries, a<br />

process which brought with it an increase in<br />

population density, and this is clearly visible<br />

in the dense network of roads and the densely<br />

built-up areas around the town, which extend<br />

to the surrounding towns and villages of<br />

Oftersheim, Plankstadt, Hirschacker, Brühl<br />

and Ketsch.<br />

Mannheim<br />

Schwetzingen<br />

Heidelberg<br />

2.<br />

Topographic map of the<br />

Rhine Valley with the cities of<br />

‘Neustadt an der Weinstraße’<br />

(far left), Mannheim and<br />

Heidelberg (far right). Shown<br />

here is the axis, approx. 50km<br />

in length, cutting through<br />

the town, the palace and the<br />

gardens and linking the hills of<br />

Königstuhl and Kalmit (mapped<br />

1994).<br />

Top = north.<br />

Königstuhl<br />

11

92<br />

12<br />

88<br />

87<br />

89<br />

90<br />

91<br />

16<br />

8<br />

86<br />

52<br />

15<br />

14<br />

50<br />

51<br />

61<br />

60<br />

64 68<br />

67<br />

55 23<br />

32 31 31 32 33<br />

57 56 57<br />

30<br />

32 31 31 32 33<br />

22 24<br />

29<br />

28<br />

11<br />

12 9 13<br />

4<br />

80<br />

2<br />

85<br />

79<br />

40<br />

49<br />

53<br />

58<br />

59<br />

65 66<br />

38 38<br />

57 56 57<br />

44 43 37 39 37<br />

48<br />

47<br />

36<br />

42<br />

41 38 35 38<br />

36<br />

45<br />

46<br />

33<br />

33<br />

34<br />

10<br />

3<br />

1<br />

80<br />

29 29<br />

29<br />

6<br />

5<br />

54<br />

34<br />

17 20<br />

7<br />

84<br />

18<br />

19<br />

81<br />

63<br />

62<br />

21<br />

83<br />

25<br />

69<br />

70<br />

73<br />

26<br />

82<br />

71 72<br />

74<br />

78<br />

77<br />

N<br />

76<br />

75<br />

27

Captions (italics denote a<br />

selection of sculptures and<br />

fountains):<br />

A THE TOWN<br />

1 Central Axis ‘Basis Palatina’<br />

(Carl-Theodor-Straße)<br />

2 Stables<br />

3 Palace square<br />

4 Former barracks of the<br />

mounted guard<br />

5 Rabaliatti House<br />

6 Palais Hirsch<br />

7 St. Pankratius<br />

8 Ysenburg Palais<br />

B THE PALACE AND<br />

OUTBUILDINGS<br />

9 Court of honour<br />

10 Guardhouses<br />

11 Palace (central block)<br />

12 Kitchens<br />

13 Upper Waterworks and<br />

ice cellar<br />

14 South quarter-circle<br />

pavilion<br />

15 Seahorse garden<br />

16 Service yard and<br />

Greenhouses<br />

17 North quarter-circle<br />

pavilion<br />

18 Palace restaurant<br />

19 Palace theatre<br />

20 Ambassadors’ House<br />

21 Coachman’s house<br />

22 Court gardener’s house<br />

23 New Orangery<br />

24 Building materials<br />

storehouse<br />

25 Disabled soldiers’ barracks<br />

26 Orangery<br />

26 Dreibrückentor<br />

27 Lower Waterworks<br />

C CIRCULAR PARTERRE<br />

28 Ages of the World urns<br />

29 Parterres à l’angloise<br />

30 Arion fountain<br />

31 Parterres de broderie<br />

32 Obelisks<br />

33 Allées en arcades<br />

34 Arbour walks (berceaux<br />

en treillage)<br />

35 Stag fountain<br />

D ANGLOISES, BOSQUETS<br />

AND ORANGERY GARDEN<br />

36 Allées en terrasse<br />

37 Lime walks (galeries de<br />

verdure)<br />

38 Four elements<br />

39 Former mirror basin<br />

40 Avenue of balls<br />

41 Southern angloise<br />

42 Temple of Minerva<br />

43 Avenue of urns<br />

44 Lycian Apollo<br />

45 Northern angloise<br />

46 Galatea basin<br />

47 Birdbath<br />

48 Pan<br />

49 Southern bosquet<br />

50 Boulingrin<br />

51 Monument in honour of<br />

gardening<br />

52 Monument commemorating<br />

archaeological finds<br />

53 Northern bosquet<br />

54 Former Quincunx<br />

55 Orangery square<br />

56 Green arcades<br />

57 Four seasons<br />

E BATHHOUSE GARDEN<br />

58 Natural theatre<br />

59 Sphinxes<br />

60 Cascade<br />

61 Temple of Apollo<br />

62 Apollo canal<br />

63 View from the temple of<br />

Apollo<br />

2. Description<br />

64 Wild boar fountain<br />

65 Water bell<br />

66 Porcelain cabinet<br />

67 Bathhouse kitchen<br />

68 Bathhouse<br />

69 Water-spouting birds<br />

70 Pheasant yard<br />

71 Pavilion and grotto<br />

72 Diorama<br />

73 Arboretum<br />

F ARBORIUM<br />

THEODORICUM/<br />

MEADOW VALE<br />

74 Meadow vale<br />

75 Roman water tower<br />

76 Obelisk<br />

77 Temple of Botany<br />

78 Basin, “Schwarzes Meerle”<br />

(“Little Black Sea”)<br />

G GREAT POND<br />

79 Great Pond<br />

80 Rhine and Danube<br />

81 Chinese bridge<br />

82 Tree nursery<br />

83 Belt Walk<br />

84 View to the village Brühl<br />

85 Central Axis ‘Basis<br />

Palatina’<br />

86 View to the „Feldherrenwiese“<br />

H TEMPLE OF MERCURY<br />

AND MOSQUE<br />

87 Temple of Mercury<br />

88 View from the Temple of<br />

Mercury<br />

89 Mosque pond<br />

90 Mosque with Turkish<br />

Garden<br />

91 Orchard<br />

92 Zähringen canal<br />

2.<br />

13

2. An<br />

14<br />

View across the town, square,<br />

palace and palace garden<br />

looking west.<br />

2. Description<br />

Aerial Perspective<br />

Schwetzingen’s appearance today, however,<br />

is still largely determined by the landscaping<br />

and building work carried out in the<br />

eighteenth-centuries. This is particularly<br />

impressive when viewed from above: an<br />

axis of approx. 50km in length leads from the<br />

Königstuhl hill above Heidelberg in the east<br />

through the whole of the Rhine plain to the<br />

Kalmit hill in the west-southwest (above the<br />

town of Neustadt an der Weinstraße). The<br />

town, the palace and the palace gardens are<br />

aligned along this axis.<br />

A road which originally led uninterrupted<br />

from Heidelberg to Schwetzingen but which<br />

is now only partially usable (extant sections:<br />

Kurfürstenstrasse and Carl-Theodor-Strasse)<br />

lends structure to the town centre and runs<br />

through the Schlossplatz (Palace Square)<br />

directly to the palace. The present pattern<br />

of roads still bears testimony to how this<br />

axis was originally made to run between<br />

two irregular settlements in what is now the<br />

town centre. Rectangular blocks of buildings<br />

along the axis now connect the two original<br />

settlements.<br />

The axis broadens out into an elongated<br />

square, the Schlossplatz, in front of the palace,<br />

which is transected by the Leimbach stream<br />

and the Karlsruher Straße and Schlossstraße<br />

roads running alongside it (B36). At the west<br />

of the square is the cour d’honneur of the<br />

palace; the sides of the square leading into the<br />

town are flanked with an almost unbroken<br />

frontage of buildings.<br />

The palace marks the end of the road<br />

originally running from Heidelberg, but the<br />

axis continues to the west in the form of paths<br />

and lines of sight running through the entire<br />

palace gardens. The palace stands at the<br />

periphery of a large circular garden made up<br />

of beds grouped around paths and avenues.<br />

This great circular parterre is technically the<br />

centre of the gardens, and is framed by two<br />

quarter-circle pavilions and two similarly<br />

shaped pergolas. The great east-west axis is<br />

transected in the centre of the parterre by<br />

an transverse axis which leads to the outer<br />

limits of the gardens in the south and extends<br />

into the town in the form of an avenue to the<br />

north.<br />

The gardens extend to the north and south<br />

asymetrically. To the west, the great circular<br />

parterre is bordered by geometrically arranged<br />

bosquets, and it is surrounded on all sides by<br />

a belt of landscape gardens. Bordering the<br />

palace and the town to the east, the outer edge<br />

of the gardens leads into the open countryside<br />

in the west. The Leimbach stream, whose<br />

course largely determines the boundary<br />

between the palace gardens and the town, is<br />

fed into channels running the whole length<br />

of the boundary; in the west the watercourses<br />

flow into an asymmetrical lake which<br />

interrupts the central axis leading from the<br />

palace. From here the axis continues along<br />

a path leading beyond the gardens to the A6<br />

motorway. The path is bordered by Ketsch<br />

Forest to the south and by farmland to the<br />

north.<br />

Detailed Description of Property<br />

Carl-Theodor-Straße<br />

From the east one enters the property via the<br />

Carl-Theodor-Straße road, which forms part of<br />

the principal east-west axis. The road is lined<br />

by espalier-trained lime trees (re-planted in<br />

2004). Apart from a few nineteenth-century<br />

buildings situated east of the Marstallstraße<br />

junction, Carl-Theodor-Straße is flanked<br />

by buildings originating in the latter half

of the eighteenth-centuries. Most of these<br />

are two-storey side-gabled houses of simple<br />

design. Alongside these, the electoral stables<br />

stands out as particularly worthy of note, a<br />

U-shaped two-storey construction of 96 metres<br />

in length, with a three-storey pavilion at each<br />

corner and a richly ornamented archway<br />

in the centre (built 1750-1752; designed by<br />

Artillery Major L’Angé). The building is<br />

now put to commercial and residential use.<br />

Further to the west, Carl-Theodor-Straße<br />

widens into the Schlossplatz, or Palace Square.<br />

Schlossplatz<br />

The square is rectangular; it measures approx.<br />

80 m x 120 m, with the shorter sides running<br />

parallel to the street. Each side is lined with<br />

two rows of chestnut trees. The southern end<br />

is characterised by two-storey, side-gabled<br />

buildings forming a continuous frontage.<br />

Built as a barracks in 1752-56 for the mounted<br />

guards (design: L’Angé), the original building<br />

was divided into five residential houses in<br />

183<strong>3.</strong> The slightly protruding corner building,<br />

which now houses the Erbprinz Hotel, was<br />

originally also part of the barracks.<br />

The north side of the square is less densely<br />

built up. In the north-eastern corner is<br />

the Palais Rabaliatti, a two-storey mansion<br />

with an arched doorway and balcony<br />

(built in 1755; designed by Franz Wilhelm<br />

Rabaliatti, Electoral Architect). Next to it is<br />

the Kaffeehaus, a neo-Baroque addition from<br />

1896, set back slightly from the square. Of<br />

particular note is the neighbouring Palais<br />

Hirsch (built in 1749; former ‚Palais Seedorf‘,<br />

probably designed by Alessandro Galli da<br />

Bibiena), a two-storey building standing apart<br />

from the Kaffeehaus in the centre of the<br />

north side of the square. Its door is framed<br />

by pilasters on each side and an ornamental<br />

panel above, and the corners of the house are<br />

adorned with rusticated pilaster strips. In the<br />

west corner stands the two-storey, front-gabled<br />

Ritter inn (construction started 1789, hall<br />

added in 1825), which leads into Schlossstraße<br />

to the north.<br />

2. Description<br />

Cour d’honneur and Palace<br />

The visitor enters the cour d’honneur, which<br />

is almost as wide as the palace square, via<br />

a bridge over the Leimbach stream. The<br />

entrance is framed by two one-storey<br />

guardhouses curving out towards the square.<br />

The courtyard is dominated by the four-storey<br />

main wing of the palace with its towers at<br />

each side. The right-angled north and south<br />

wings (built 1711-1712) resemble, with their<br />

mansard roofs, the style of the buildings<br />

in the palace square, but are set apart by<br />

a central projecture with pointed gable in<br />

the centre of each wing and four doorways<br />

framed with aediculae.<br />

The north wing now houses Schwetzingen’s<br />

Tax Office, and the south wing the School of<br />

Court Registrars.<br />

2.<br />

View from the palace roof over<br />

the court of honour, palace<br />

square and town.<br />

The Carl-Theodor-Straße west<br />

towards the palace square.<br />

15

2. The<br />

16<br />

Cour d’honneur of the palace.<br />

View from the palace roof west<br />

towards the parterre.<br />

2. Description<br />

main wing originates in the fourteenthcenturies;<br />

repeatedly altered since then and<br />

extended to the west, its current form dates<br />

from 1716. It displays a clear contrast to the<br />

two side wings, with rusticated stonework<br />

extending up to the first floor in the centre<br />

and to the eaves on the two symmetrical<br />

towers, which are adorned with cambered<br />

turrets. The building is set back in the centre,<br />

creating a courtyard enclosed on three sides.<br />

Here we find the east facade of the main<br />

wing, positioned at a slight angle to the other<br />

facades in the cour d’honneur. The ground<br />

floor houses the palace administration and<br />

the Building and Maintenance Department<br />

(Schwetzingen branch) of the State Agency for<br />

Property Assets and Construction. The upper<br />

floors are accessed via two straight flights of<br />

stairs. They form the palace museum and are<br />

furnished in the style of the latter half of the<br />

eighteenth-centuries. The main wing retains<br />

stucco ceilings from the reign of Carl Philipp<br />

(1716-1742) and furnishings from the reign of<br />

Carl Theodor (1742-1799). The second floor<br />

has retained rare panorama wallpaper in situ,<br />

put up by the Zuber company from Rixheim<br />

at the beginning of the nineteenth-centuries<br />

(1804).<br />

The main wing’s east-facing facade has an<br />

archway in the centre, through which one<br />

enters the gardens.<br />

Circular Parterre<br />

Since the palace gardens are not visible<br />

from the cour d’honneur, the archway<br />

to the gardens resembles a threshold to<br />

another world: after the enclosed space of<br />

the courtyard, the gardens fan out in a wide<br />

open space beyond the slightly raised terrace.<br />

Immediately visible are the gravel paths,<br />

lawns, flower beds, ornamental box hedges<br />

and geometrically clipped lime trees of the<br />

great circular parterre. At the centre is a<br />

fountain with jets attaining almost 14m in<br />

height. The parterre has a diameter of approx.<br />

322m and is framed by two quarter-circle<br />

pavilions, by arcades of clipped lime, and by<br />

quarter-circle trellised walks (“bercaux en<br />

treillage”) facing the pavilions.<br />

The quarter-circle pavilions (north pavilion<br />

built 1748-50, designed by Alessandro da<br />

Bibiena; south pavilion built 1752-54, designed<br />

by Franz Wilhelm Rabaliatti) are one-storey<br />

constructions with large, arched French doors<br />

along their whole length and each have five<br />

projecting sections. These sections have<br />

hipped mansard roofs, contrasting with the<br />

plain gabled roofs of the sections joining<br />

them. While the south pavilion’s two halls<br />

(the Hunt Hall and the Mozart Hall) boast<br />

richly ornamented stucco ceilings, those in the<br />

north pavilion are plain in style. The north<br />

pavilion leads to the palace theatre (Nicolas de<br />

Pigage, 1752-1753), which has no facade of its<br />

own. The auditorium is made of wood and is<br />

shaped in the form of a horseshoe, with two

projecting galleries, and stalls gently sloping<br />

towards the stage. The curved balcony rails<br />

are covered in fabric, and the entire interior<br />

of the theatre is decorated in shades of grey<br />

and ochre, with neoclassical elements such as<br />

lions‘ heads moulded in papier-mâché. The<br />

proscenium arch is defined by Corinthian<br />

pilasters in blue-green marbling. Resplendent<br />

above the stage is the coat of arms of Prince<br />

Elector Carl Theodor.<br />

The circular parterre itself is transected by<br />

a central path (allée principale) and two<br />

parallel paths (allées secondaires), which are<br />

crossed in the centre by three identical paths<br />

running at right angles to them. There are<br />

also paths running diagonally through the<br />

circle and along its cirumference in front of<br />

the quarter-circle pavilions; these paths define<br />

eight sections in the form of sunken lawns<br />

(boulingrins).<br />

From the slightly raised terrace in the east, a<br />

broad strip stretches to a fountain with two<br />

water-spouting stags in the west (known as the<br />

stag fountain, Peter Anton von Verschaffelt,<br />

1766-1769). While the lateral paths take the<br />

form of tree-lined avenues, the centre path<br />

is free of trees. The east-west extension is<br />

emphasised within the circular parterre by<br />

two lawn parterres lined with flower beds<br />

(parterres a l’angloise), the central, circular<br />

pool (the Arion Fountain: approx. diameter<br />

30m, attributed to Barthélemy Guibal, first<br />

half of the 18th-centuries, probably from the<br />

gardens of Lunéville Palace), four parterres<br />

de broderie surrounding the fountain, and<br />

a symmetrical pattern of lawn parterres<br />

stretching to the west. The transversal paths<br />

are all flanked with trees, including the path<br />

in the centre. The elongated lawns between<br />

the paths are also lined with a row of trees<br />

on each side, so that altogether there are ten<br />

parallel rows of trees along the transverse<br />

(north-south) axis. Oval lawns mark the ends<br />

of the lateral paths at the edge of the circular<br />

parterre; only the central avenue continues<br />

beyond the parterre to the north and south<br />

boundaries of the gardens.<br />

2. Description<br />

The circular parterre is rich in statuary. The<br />

four oval pools in the centre of the lawn<br />

parterre are adorned with cherubs sitting<br />

on swans and herons, from whose beaks<br />

revolving water jets spout forth (attributed<br />

to Barthélemy Guibal, first half of the<br />

18th-centuries, probably from the gardens<br />

of Lunéville Palace). Further decorative<br />

elements are found in the form of the four<br />

urns on the terrace symbolising the four Ages<br />

of the World (Peter Anton von Verschaffelt,<br />

2.<br />

Obelisk in the transverse axis.<br />

South quarter-circle pavilion,<br />

exterior facing the circular<br />

parterre.<br />

17

2. 1762-1766),<br />

18<br />

Southern angloise, Temple<br />

of Minerva.<br />

Northern angloise, Rock of Pan.<br />

2. Description<br />

and four obelisks with teardrop<br />

rustication on the lawns of the transverse axis<br />

(Peter Anton von Verschaffelt, 1766-1769).<br />

By the time the visitor reaches the Arion<br />

fountain, he is forced to abandon the idea<br />

that the gardens are as straightforward as<br />

a first impression from the terrace would<br />

suggest. At this point it becomes clear that he<br />

has entered another world, entirely separate<br />

from the town. The many and varied views<br />

and glimpses (the transverse avenue, the<br />

spires in the town, the Temple of Minerva,<br />

the orangery, the cupolas and minarets of<br />

the mosque, etc.) tempt the visitor to explore<br />

further, while other paths, new focal points<br />

and unexpected finds are hinted at but still<br />

remain largely hidden. It is this hidden world<br />

beyond the circular parterre that constitutes<br />

the unique appeal of the palace gardens.<br />

Principal Axis up to the Lake<br />

The principal axis provides the initially<br />

most obvious route to take. The central<br />

path ends at the stag fountain, closing the<br />

circle of the great parterre. The ground to<br />

the west is approximately one metre lower;<br />

but the transition is gentle, and although the<br />

wide strip leading from the palace becomes<br />

narrower at this point, it continues along the<br />

same axis, extending the line of sight beyond<br />

the circular parterre towards the west. The<br />

lateral paths of the circular parterre extend<br />

a little beyond its boundaries, but soon end<br />

in low-set arcades of clipped limes (berceaux<br />

naturels en arcades), forming a U-shaped<br />

terrace with a rectangular lawn, from which<br />

steps lead down to the lower-lying area. Up<br />

to the beginning of the nineteenth-centuries,<br />

an area of water fed by the stag fountain and<br />

known as the mirror pool was to be found<br />

here. The terrace is adorned with cone-shaped<br />

yews and a total of eight lead vases (Peter<br />

Anton von Verschaffelt, before 1773), and<br />

framed by four seated figures, personifications<br />

of the four elements (Peter Anton von<br />

Verschaffelt, 1766-69). Ramps from the lawns<br />

of the circular parterre lead to two parallel<br />

paths forming an avenue which continues<br />

to the lake located at the western edge of the<br />

gardens.<br />

The avenue is flanked externally by hedges,<br />

and between the two paths lies a lawn with<br />

eight herm pedestals, which are topped by<br />

golden spheres rather than busts (Konrad<br />

Linck, c. 1760?). Two paths cross the avenue at<br />

right angles, enticing the visitor to explore the<br />

bosquets to the north and south.<br />

Angloises<br />

Next to the circular parterre to the west are<br />

small landscape areas known as angloises<br />

on account of the meandering paths which<br />

were originally to be found here. The centre

pavilion of the southern arbour walk frames<br />

the view of the Temple of Minerva (Nicolas<br />

de Pigage, 1767-1773, in collaboration with<br />

the sculptor Konrad Linck), a prostylos with<br />

Corinthian columns. It stands in a grove of<br />

irregularly planted trees and has a pool in<br />

front of it. A further feature of the southern<br />

angloise is the “avenue of urns”, an area lined<br />

by tall hedges to form a salle de verdure,<br />

whose focal point is a marble sculpture of the<br />

Lycian Apollo (Paul Egell, c.1746). The avenue<br />

is adorned with eight lead urns (Konrad Linck,<br />

before 1769) und pillar-shaped thujas.<br />

In the northern angloise, the Galathea<br />

fountain (Gabriel de Grupello, 1716, brought<br />

to Schwetzingen from Düsseldorf in 1767<br />

at the behest of Carl Theodor), stands in the<br />

location occupied by the Temple of Minerva<br />

in the south. The counterpart of the southern<br />

avenue of urns is the birdbath or “zig-zag<br />

pool”, a long hedged area in which shallow<br />

watercourses meander from each end towards<br />

a central pool, which sports two cherubs<br />

riding sea monsters (attributed to Barthélemy<br />

Guibal, first half of the 18th-centuries). There<br />

are eight lead vases (Anton von Verschaffelt,<br />

c. 1770) and four benches placed in the oval<br />

hedged area around the pool. The whole area<br />

is dominated by an oversized marble statue of<br />

Bacchus (Andrea Vacca, prob. first quarter of<br />

the 18th-centuries, brought to Schwetzingen<br />

around 1766). A path leads off at right<br />

angles to the birdbath and ends at a tufa rock<br />

discharging water into a semi-circular pool,<br />

atop which sits a statue of Pan (Peter Simon<br />

Lamine, 1774).<br />

Bosquets<br />

The bosquets in the west of the angloises<br />

are crisscrossed by a symmetrical pattern of<br />

paths, all of which are lined with hornbeam<br />

hedges. There are stone benches at the ends<br />

of the paths, and various types of topiary.<br />

At the centre of the southern bosquet is an<br />

oval sunken lawn (“boulingrin”) with two<br />

monuments standing nearby (Peter Anton von<br />

Verschaffelt, 1771). The monument at the<br />

south end marks archaeological finds, and the<br />

2. Description<br />

north monument celebrates Carl Theodor as<br />

the creator of the garden (“Look and admire,<br />

wanderer! She who did not beget this also<br />

marvels, the great mother of all things, Nature.<br />

Carl Theodor created this place as a refuge<br />

from his labours for himself and his own. He<br />

erected this monument in 1771.”)<br />

At the centre of the northern bosquet is an<br />

open square space originally featuring a<br />

quincunx pattern of sculpted trees.<br />

The bosquets are bordered to the north,<br />

west and south by a raised avenue flanked<br />

by chestnut trees (an allée en terrasse). Two<br />

longer north-south paths run through the<br />

bosquets to two large independent gardens:<br />

the open-air theatre with the Temple of<br />

Apollo and adjacent bathhouse in the north,<br />

and in the south the Turkish garden with the<br />

mosque.<br />

Open-Air Theatre and Apollo Temple<br />

The open-air theatre (Nicolas de Pigage,<br />

1762) has a low-lying auditorium watched<br />

over by six sphinx figures (Peter Anton von<br />

Verschaffelt, before 1773) and a moderately<br />

elevated stage framed by rows of hedges<br />

forming the wings. Behind the stage, the<br />

Temple of Apollo (Nicolas de Pigage, 1762)<br />

rises above a wide artificial waterfall.<br />

2.<br />

The natural theatre and Temple<br />

of Apollo, east to west.<br />

19

2.<br />

View of the bathhouse from the<br />

wild boar basin.<br />

20<br />

Bathhouse, bathroom.<br />

2. Description<br />

Flights of steps lead up on both sides of the<br />

waterfall, but the temple can only be reached<br />

via a complex network of irregular steps or<br />

via the grotto-like passageways built into<br />

the artificial rock on which it stands. From<br />

the theatre side, then, the temple appears to<br />

stand upon a large rock; but on the east side<br />

the base is revealed as a multi-level platform,<br />

with the temple on the top level. The temple,<br />

with its twelve Corinthian columns and<br />

coffered ceiling, is named after the marble<br />

statue of Apollo which it houses (Peter Anton<br />

von Verschaffelt, before 1773). The elaborate<br />

lattice designs adorning the platform take up<br />

the theme of the sun god, with golden reliefs<br />

depicting a face surrounded by rays.<br />

Bathhouse<br />

To the north of the Temple of Apollo is the<br />

bathhouse complex, with a grotto containing<br />

the sculpture of a wild boar (sculpture<br />

attributed to Barthélemy Guibal, first half<br />

of the 18th-centuries, probably from the<br />

gardens of Lunéville Palace), the bathhouse<br />

itself, an oval pool with water-spouting<br />

birds, and a pavilion housing a diorama, a<br />

trompe-l’oeil feature creating the illusion of<br />

a vista through an artificial grotto out into<br />

the open countryside. The various elements<br />

of the complex, which are all aligned along<br />

a longitudinal axis, come together to create<br />

an overall work of art, with architecture,<br />

sculpture, landscape gardening and painting<br />

complementing each other to perfection.<br />

The ingenious layout of the bathhouse and<br />

its elaborate décor obscure the boundaries<br />

between exterior and interior: the semicircular<br />

anterooms connecting each side of the<br />

building with the central oval reception<br />

room reduce the time taken to walk through<br />

the bathhouse to the briefest of sojourns<br />

along the length of the otherwise open-air<br />

complex; and the oval painting entitled<br />

‘Aurora banishes the night’ which covers the<br />

ceiling (artist: Nicolas Guibal, between 1768<br />

and 1775) creates the illusion of a space open<br />

to the sky. Only by deviating from the linear<br />

layout of the complex does one gain access to

the other rooms in the bathhouse, which all<br />

retain the original décor. Carl Theodor’s study<br />

is lined with mirrors and landscape murals<br />

(Ferdinand Kobell, c. 1775) which serve to<br />

soften the limits imposed by the walls. The<br />

tea room is decorated with ornate Chinese<br />

wallpaper. A resting room and a bathroom<br />

with a large walk-in bath complete the picture<br />

as far as the number of rooms is concerned;<br />

but it is impossible to do justice in such a<br />

description to the wealth of detail afforded by<br />

the bathhouse décor and furnishings. Suffice<br />

to say that all the elements contributing to the<br />

overall impression, from the bronze griffons<br />

supporting the console tables in the oval room<br />

through the neoclassical furnishings of the<br />

side rooms to the snake’s-head taps in the<br />

bathroom, bear testament to artistic skills of<br />

the highest degree.<br />

The sculptors Peter Anton Verschaffelt (1710-<br />

1793) and Konrad Linck (1730-1793), painters<br />

Ferdinand Kobell (1740-1799) and Nicolas<br />

Guibal (1725-1784), stucco craftsman Joseph<br />

Anton Pozzi (1732-1811), and the cabinet<br />

makers Franz Zeller and Jacob Kieser were all<br />

involved in the creation of the bathhouse; but<br />

their works gain immeasurably from being<br />

integrated into a whole, and for this the credit<br />

must go to the designer Nicolas de Pigage<br />

(1723-1796). Pigage’s creation is characterised<br />

by the skilful integration of genuine and<br />

artificial elements, such as real marble<br />

and marble-effect stucco, tear-drop reliefs<br />

and trompe l’oeil paintings of such reliefs,<br />

bronze and bronzed stucco, which constantly<br />

challenge the visitor’s judgment while<br />

ensuring that the “fake” elements hold their<br />

own alongside the “genuine”. This interplay<br />

continues outside the bathhouse.<br />

2. Description<br />

Fountain with water-spouting birds, diorama<br />

Leaving the bathhouse by the north entrance,<br />

one finds oneself at a remarkable fountain<br />

known as that of the water-spouting birds. A<br />

semicircular arbour with elaborate latticework<br />

frames an oval pool; in the centre of this pool<br />

is an eagle-owl with prey, which is bombarded<br />

from above with water spouting from the<br />

beaks of birds perched on the top of the<br />

latticework. Around the pool are two small<br />

pavilions with ornately decorated seating<br />

areas, and four aviaries. The song of the real<br />

birds kept in the aviaries rounds off the effect<br />

of the scene. Paths lined in latticework lead<br />

from this space to small balconies affording<br />

views of the surrounding parts of the gardens.<br />

A courtyard leads from the water-spouting<br />

birds to a long arbour walk (berceau en<br />

treillage). At its end is a pavilion with an<br />

artificial grotto decorated with shells and<br />

semi-precious stones, aligned as an extension<br />

of the walkway. The far wall of the grotto has<br />

a semi-circular opening, and beyond this is a<br />

slightly concave free-standing wall on which a<br />

fresco of a landscape is painted. In reality, the<br />

visitor’s view ends at this wall; but the effect<br />

Bathhouse complex, waterspouting<br />

birds.<br />

2.<br />

21

2.<br />

22<br />

Mosque and cloister<br />

looking west.<br />

Temple of Mercury.<br />

2. Description<br />

is of a vista out over a distant paradisiacal<br />

landscape.<br />

Mosque<br />

To the south of the bosquets is the Turkish<br />

garden with its mosque. The mosque<br />

complex consists of a cloister-like latticework<br />

colonnade on the east side (Nicolas de Pigage,<br />

1779-1784) and a main building (Nicolas de<br />

Pigage, 1782-1786) flanked by two minarets<br />

(Nicolas de Pigage, c. 1786-1795) in the west.<br />

The minarets project slightly from the west<br />

facade of the main building, to which they<br />

are connected by inward-curving walls. They<br />

resemble oversized columns whose smooth<br />

shaft is interrupted only by a single ring<br />

and whose leaf-adorned capitals support an<br />

additional structure. It is this additional<br />

structure that establishes the columns as<br />

minarets: they are crowned with two onionshaped<br />

forms above a turret surrounded by a<br />

fenced balcony.<br />

The facade proper consists of a cube-shaped<br />

single storey with parapet. Entry is gained<br />

through a portico, and any severity in the<br />

overall effect is obviated by windows with<br />

round and pointed arches, and panels with<br />

Arabic inscriptions. Behind the entrance<br />

towers a round tambour capped with a slatecovered<br />

dome. The interior of the mosque<br />

consists of a circular central room with eight<br />

columns and four niches. A door facing the<br />

entrance leads off to the cloister to the east,<br />

and two further openings at the sides lead<br />

to adjoining rooms. The interior is richly<br />

ornamented, with particularly salient Arabic<br />

inscriptions (which here too are translated<br />

into German) and unusual oriental-style<br />

motifs such as crescent moons, rosettes and<br />

five-pointed stars surrounded by rays.<br />

Over the adjoining rooms are galleries<br />

connected to the central room by a window.<br />

A passage leads from the main building<br />

to the rectangular cloister, which is clad<br />

in trelliswork screens and is open on both<br />

sides. In contrast to the berceaux en treillage,<br />

however, the cloister is covered with an<br />

intricately designed slate roof supported

y wooden columns. The trellises, too, are<br />

elaborate in design and are adorned with<br />

various decorative elements. At the corners of<br />

the cloister stand octagonal pavilions capped<br />

with oval tambours and domes. The interior<br />

walls of the pavilions have mock supports in<br />

the shape of palm trees, and the ceilings of<br />

the domes feature a night sky with moon and<br />

stars. The cloister ceilings, too, are decorated<br />

with a pattern of stars.<br />

Pavilions are integrated into the centre of<br />

each long side of the cloister, at the point of<br />

entry from the main building in the west,<br />

and to mark access from the garden in the<br />

east. They are decorated with aphorisms in<br />

Arabic and German. Six more pavilions are<br />

located beyond the cloister, connected to it at<br />

right angles by covered passages. The most<br />

remarkable attribute of the pavilions is the<br />

“priests’ closets” they contain, small rooms<br />

decorated so as to create the illusion of costly<br />

stone materials, with stained-glass domes<br />

set in the centre of the ceiling. Perhaps the<br />

most eye-catching feature of the mosque is<br />

the intricate roof, with its interplay of various<br />

roof types all covered in slate, four gold-leaf<br />

crowns on the domes of the corner pavilions,<br />

and countless gold-leaf crescents dotted across<br />

the whole structure. Seen from the east, the<br />

roofscape gains in grandeur, set as it is against<br />

a background of the central dome flanked by<br />

minarets.<br />

The cloister is embedded in an oriental-style<br />

garden with meandering paths sloping gently<br />

upwards as one leaves the mosque.<br />

Landscape Gardens and Landscape Areas<br />

Outside Gardens<br />

The formal gardens have a geometrical layout<br />

and are surrounded by a belt of landscape<br />

gardens. To the west of the mosque is<br />

a pond, and behind this a hill on which<br />

the Temple of Mercury (Nicolas de Pigage,<br />

1787-1792) is located. The south side of the<br />

hill is fashioned in the form of a cliff, with a<br />

narrow passage leading into a vaulted area<br />

under the temple. The temple itself is an<br />

artificial ruin in the form of a three-storey<br />

2. Description<br />

2.<br />

View from the Roman water<br />

tower into the ‘Wiesentälchen’.<br />

Temple of Botany.<br />

23

2.<br />

24<br />

Lower waterworks.<br />

Upper waterworks.<br />

2. Description<br />

belvedere with a triangular form allowing<br />

the visitor to look out over both the mosque<br />

and the surrounding landscape. A belt walk<br />

meanders along the boundary of the gardens<br />

to the section of the lake which bulges out<br />

to the west, and beyond this through an<br />

assortment of clumps to what is known<br />

as the Wiesentälchen, or Meadows. At its<br />

western end are the Temple of Botany, the<br />

Roman water-fort and the obelisk. Embedded<br />

in a landscape including canals, bridges<br />

and artificial rocks, the overall effect of this<br />

group of buildings is very picturesque. The<br />

Temple of Botany (Nicolas de Pigage, 1778) is<br />

a cylindrical building whose exterior surface<br />

resembles the trunk of an oak tree. Two<br />

sphinx figures (Konrad Linck, c. 1778) flank<br />

the steps leading up to the entrance. Inside<br />

there are two decorative vases (Konrad Linck?)<br />

and a marble statue of Ceres (Francesco<br />

Carabelli, c. 1775). The walls are decorated<br />

with stuccoed-relief portraits of the botanists<br />

Theophrastus, Pliny the Elder, Linnaeus and<br />

Tournefort; between these and the coffered<br />

ceiling are representations of the twelve signs<br />

of the zodiac.<br />

Nearby are the artificial ruins of a Roman<br />

water-fort set (Nicolas de Pigage, 1779) within<br />

arches reminiscent of an ancient aqueduct. A<br />

waterfall emanates from the centre of the far<br />

wall into the canal flowing in front of the fort.<br />

Steps lead to a vantage point from which the<br />

whole complex is visible: one sees a second<br />

aqueduct connecting the water-fort with the<br />

lower waterworks located beyond the gardens.<br />

To the west one sees the Arborium<br />

Theodoricum, also known as the<br />

Wiesentälchen or Meadows, a narrow strip of<br />

land bordered by a canal on both sides and<br />

resembling a forest clearing with a variety of<br />

clumps; two paths lead along the Meadows,<br />

ending at the Dreibrückentor, the point at<br />

the northern end of the gardens where the<br />

transverse axis crosses over into the town.

Areas Bordering the Gardens, and<br />

Buildings Directly Adjacent to the Gardens:<br />

Waterworks, Envoys’ Lodgings, Palais<br />

Ysenburg<br />

The palace gardens are enclosed on all sides<br />

in the original fashion, with moats, fences and<br />

ha-has; these devices protect the gardens from<br />

trespass while often blurring the boundaries<br />

between outside and inside the grounds.<br />

The upper and lower waterworks immediately<br />

adjacent to the gardens continue to fulfil<br />

their original function, powered by the<br />

Leimbach stream. The lower waterworks<br />

(built after 1774 by Nicolas de Pigage), which<br />

is connected to the Roman water-fort via an<br />

aqueduct, retains a large part of the original<br />

pump machinery and a bone mill (dated 1779).<br />

The upper waterworks (built by Nicolas de<br />

Pigage around 1760-1771) is immediately<br />

adjacent to the north cour d’honneur wing of<br />

the palace. The ground floor today houses the<br />

customer service centre of the Tax Office. As<br />

in the lower waterworks, the original pump<br />

technology has been preserved; additionally,<br />

the upper waterworks also retains a two-storey<br />

icehouse originating in the period when the<br />

waterworks was built.<br />

Schwetzingen’s status as home to the court is<br />

underlined by the presence of mansions such<br />

as the envoys‘ lodgings (built around 1723)<br />

and the Palais Ysenburg (around 1769).<br />

2. Description<br />

2.<br />

25

2. 2.b)<br />

26<br />

2. Description<br />

History and Development<br />

Early History<br />

Schwetzingen’s history can be traced back<br />

to the Neolithic period (c. 5000 BC). Finds<br />

from the Celtic (300 BC), the Suebi Nicrenses<br />

(100 AD) and the Merovingioan (500-700 AD)<br />

periods attest to the fact that its favourable<br />

location in the alluvial cone of the Neckar<br />

continued to be exploited by later settlers.<br />

It was first mentioned as “Suezzingen”<br />

(“belonging to Suezzo’s homestead”) in<br />

the Lorsch codex for the year 766, and<br />

in the records of 805 and 807 there was<br />

an upper and a lower village. These two<br />

foci of settlement can still be discerned in<br />

Schwetzingen’s street layout.<br />

From 1350 there is evidence of a castle in<br />

Schwetzingen belonging to the aristocratic<br />

Von Erlickheim family; in 1427 it passed<br />

into the possession of the Counts Palatine<br />

and started to be regularly used as a base for<br />

hunting in the surrounding forests.<br />

The village and the castle were razed to the<br />

ground in 1635, during the Thirty Years War.<br />

The castle was rebuilt from 1656 by Prince<br />

Elector Carl Ludwig, but destroyed again<br />

in 1689 during the War of the Palatinian<br />

Succession.<br />

Eighteenth-Century:<br />

Conversion to Summer Residence<br />

Prince Elector Johann Wilhelm (1658-1716;<br />

Prince Elector from 1690) commissioned<br />

the rebuilding of the site from 1698 to 1717<br />

and had it extended as a Baroque palace: on<br />

the east side the wings overlooking the cour<br />

d’honneur were added, on the west the main<br />

wing doubled in size. These additions to the<br />

original complex were designed to stand in<br />

strict alignment with the axis formed by a<br />

line drawn across the Rhine plain between<br />

the Königstuhl and Kalmit hills. When<br />

Carl Philipp (1661-1742) became Prince<br />

Elector in 1716, the main electoral residence<br />

moved from Heidelberg to Mannheim,<br />

and Schwetzingen was used as a hunting<br />

lodge and summer residence. In 1718, Carl<br />

Philipp’s architect Alessandro Galli da Bibiena<br />

constructed an orangery to the west of the<br />

palace (demolished around 1754) and created<br />

a pleasure garden between the orangery and<br />

the palace.<br />

1742-1799: The Era of Carl Theodor, the<br />

“Golden Age of the Electoral Palatinate”<br />

The accession to power of Carl Theodor (1724-<br />

1799) in 1742 marked the beginning of a new<br />

era in Schwetzingen’s history. For several<br />

months every summer between 1743 and<br />

1778, Schwetzingen was home to the electoral<br />

household along with the court orchestra, thus<br />

functioning as the focal point of the Electoral<br />

Palatinate. Work was carried out throughout<br />

these thirty-five years to transform the palace<br />

and gardens into an ideal summer residence,<br />

one in which pleasure (recreation, enjoyment<br />

and amusement) and necessity (the business<br />

of ruling) could be perfectly combined.<br />

From the 1750s onwards, the main residence<br />

of Carl Theodor in Mannheim and his<br />

summer residence in Schwetzingen evolved<br />

into a centre of scientific and artistic<br />

excellence of Europe-wide significance.<br />

Schwetzingen’s function as a “court of<br />

muses”, a space in which the arts and sciences<br />

were patronised and given free reign to<br />

flourish, played an important part in this<br />

process. Schwetzingen offered a scope for<br />

experimentation which would have been<br />

unthinkable at Mannheim, bound as the main<br />

court was to strict protocol; Schwetzingen<br />

provided a space for the implementation<br />

of ideas that in Mannheim were fostered<br />

through the establishment of academies<br />

(1763: Academy of Sciences; 1757: Sculptors‘<br />

Academy; 1770: Drawing Academy; 1775:<br />

German Society). This is attested not only<br />

by the rich artistry found at the summer<br />

residence, but also by projects such as the<br />

surveying of the Electoral Palatinate, which<br />

used as its base the axis running from<br />

Heidelberg to Schwetzingen (Christian Mayer,<br />

1763: publication of the manuscript Basis

Palatina; 1773: publication of the survey map<br />

Map of Palatine at a Scale of 1:75000) In 1761<br />

Schwetzingen was one of approximately 120<br />

places across the world in which the Transit of<br />

Venus (the passage of Venus across the face of<br />

the sun) was observed and measured.<br />

The advancement of theatre and music also<br />

contributed to Schwetzingen’s European<br />

standing: nowhere in Europe was the<br />

programme of a theatre more varied. It<br />

was in Schwetzingen that the first opera<br />

was written and staged in German (Ignaz<br />

Holzbauer, 1776: Günther von Schwarzburg),<br />

and Schwetzingen’s theatre and opera<br />

repertoire was generally critical of the<br />

established hierarchy, presenting the public<br />

with Enlightenment ideals. Visitors such<br />

as Voltaire (1753), whose tragedy Olimpie<br />

premiered in the palace theatre in 1762,<br />

Leopold Mozart with his children Wolfgang<br />

und Nannerl (1763), and Casanova (1767)<br />

all bear witness to the appeal Schwetzingen<br />

exerted during this period.<br />

Prince Elector Carl Theodor was the focal<br />

point of Electoral Palatinate society. Born<br />

at Drogenbos Palace near Brussels in 1724,<br />

Carl Theodor spent his childhood in Belgium.<br />

After his father’s death in 1733 he succeeded<br />

to the status of heir to the Electoral Palatinate,<br />

and from 1734 onwards he was educated<br />

in Mannheim by tutors including the Jesuit<br />

Francois de Fegely, known as “Father Seedorf”<br />

(1691-1758), who retained considerable<br />

influence over Carl Theodor right up until<br />

his death in 1758. Another figure who<br />

enjoyed a position of influence at the court<br />

was Carl Theodor’s wife, Elisabeth Auguste, a<br />

cousin and grandchild of Prince Elector Carl<br />

Philipp who had grown up in Mannheim and<br />

Schwetzingen.<br />

2. Description<br />

Creation of Carl Theodor’s<br />

“Garden Residence”<br />

Finding in Mannheim an already functioning<br />

courtly residence with what was at the time<br />

one of the largest castles in existence, Carl<br />

Theodor chose Schwetzingen as the place<br />

to exercise his architectural whims, and<br />

commissioned the building of an entirely<br />

new kind of residence, one that incorporated<br />

already existing structures but which focused<br />

on the gardens.<br />

The expansion of Schwetzingen that started in<br />

1748 was planned so as to extend features of<br />

the cour d’honneur eastwards into the town;<br />

this is visible in the height of the buildings<br />

and the roof types chosen. Square blocks<br />

of houses were built along the main axis to<br />

connect the two original mediaeval settlement<br />

foci. With the annual use of Schwetzingen as<br />

the Prince Elector’s summer residence came<br />

the construction of small mansions at the<br />

boundary of palace and town: Palais Hirsch<br />

(1749; built for Carl Theodor’s confessor, the<br />

Jesuit priest Franz Joseph Seedorf), Palais<br />

Rabaliatti (1755; built for the court architect<br />

Franz Wilhelm Rabaliatti); the Forestry<br />

Office (1760; originally home to the electoral<br />

gamekeeper), Palais Ysenburg (construction<br />

started 1769; built for the electoral chief<br />

gardener Van Wynder).<br />

2.<br />

Portrait of Prince Elector Carl<br />

Theodor by Johann Georg<br />

Ziesenis, 1758.<br />

27

2. The<br />

28<br />

Plan for the circular parterre.<br />

Johann Ludwig Petri, 175<strong>3.</strong><br />

2. Description<br />

expansion of the palace which also began<br />

in 1748 focused entirely on the gardens: the<br />

existing orangery was sacrificed to make way<br />

for the north quarter-circle pavilion (1748-<br />

1750). After several rounds of planning,<br />

the south quarter-circle pavilion including<br />

ballrooms was added to mirror the north<br />

pavilion (1750-1752). By this time Nicolas<br />

de Pigage (1723-1796) was an established<br />

figure at Schwetzingen, having first been<br />

commissioned in 1749. Pigage, a Paris-trained<br />

architect originally from Lunéville (Lorraine),<br />

was involved in various construction projects<br />

before eventually being appointed as director<br />

of garden construction in 1761. The palace<br />

theatre was constructed in the course of one<br />

year (1752-1753); and Schwetzingen was<br />

made a market town in 1759, an indication of<br />

the growth in status the town had experienced<br />

since becoming Carl Theodor’s summer<br />

residence.<br />

Between 1761 und 1764 the palace was<br />

extended again, this time through the addition<br />

of the “kitchen wing“.<br />

In 1768, in conscious deviation from what<br />

was accepted practice at existing courtly<br />

residences, Pigage commenced construction<br />

of a small maison de plaisance known as<br />

Carl Theodor’s bathhouse. The bathhouse<br />

was built in its own walled-off garden, and<br />

with its reception rooms, study, bedroom<br />

and bathroom, along with the freestanding<br />

“bathhouse kitchen“ located nearby, it<br />

provided a self-contained retreat for the<br />

prince, still within the gardens but shielded<br />

from the hustle and bustle of the palace.<br />

While elaborately appointed, the bathhouse<br />

testifies to a certain modesty on Carl<br />

Theodor’s part, demonstrating as it does a<br />

renunciation of absolutist self-aggrandisement<br />

and confirming Carl Theodor as a man of the<br />

Enlightenment.<br />

Extension of the Gardens<br />

In 1753, Johann Ludwig Petri (1714-1794), a<br />

landscape gardener who initially worked at<br />

Zweibrücken, delivered a plan for a circular<br />

parterre which was to be positioned so as<br />

to be framed by the quarter-circle pavilions.<br />

This plan was largely implemented, and the<br />

circular parterre now forms the centre of the<br />

palace gardens.<br />

The parterre was conceived as a richly<br />

decorated feature from the beginning, as is<br />

demonstrated by a string of contracts drawn<br />

up with the sculptor Peter Anton Verschaffelt.<br />

1761 saw the construction of a new orangery,<br />

and work was started in the following year on<br />

the Temple of Apollo and the open-air theatre.<br />

Water supply to the eastern half of the<br />

gardens, along with the level of water pressure<br />

necessary for the water-spouting birds to

function, was guaranteed by the construction<br />

in 1771 of the Upper Waterworks in the<br />

immediate vicinity of the palace, a hydropowered<br />

pumping station with elevated<br />

water tank. By 1774 the Lower Waterworks<br />

had been added at the north-west edge of the<br />

gardens.<br />

In 1776 Nicolas de Pigage travelled to<br />

England, where he met Friedrich Ludwig<br />

von Sckell (1750-1823), a young man who<br />

had grown up in Schwetzingen and who<br />

had spent several years studying English<br />

landscape gardening at Carl Theodor’s behest.<br />

The following year, Pigage and Sckell started<br />

work together on the Arborium Theodoricum<br />

(known locally as the Wiesentälchen, or<br />

Meadows), a narrow strip of land that was<br />

fashioned so as to be reminiscent of natural<br />

landscapes: the resulting masterpiece was the<br />

first landscape garden in Southern Germany.<br />

In 1778, Carl Theodor moved to Munich.<br />

Although the prince took a number of artists<br />

with him, Nicolas de Pigage and Friedrich<br />

Ludwig von Sckell stayed at Schwetzingen in<br />

order to complete their work on the gardens,<br />

Pigage remaining there until his death in<br />

1796, while Sckell eventually left in 1804.<br />

That the gardens at Schwetzingen were<br />

considered outstanding even during<br />

their creation is borne out by the detailed<br />

disquisition dedicated to them in the fifth<br />

volume of Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld’s<br />

Theorie der Gartenkunst (Theory of Garden<br />

Design), published in Leipzig in 1779-1785.<br />

The years between 1779 and 1795 saw the<br />

construction of the garden mosque, which is<br />

now the last extant example of its kind.<br />

The 1783 as-is plan by Friedrich Ludwig von<br />

Sckell gives a precise outline of the largely<br />

completed gardens (Munich, Bavarian Dept.<br />

for State Castles, Gardens and Lakes).<br />

The Temple of Mercury, which stands on an<br />

artificial hill across a lake from the mosque,<br />

was built between 1784 and 1792.<br />

Work on the gardens was eventually<br />

completed around 1795. A comprehensive<br />

inspection lasting several weeks was carried<br />

2. Description<br />

out during this year, and the report, the<br />

protocollum commissionale, has been<br />

preserved. It lists the entire inventory of<br />

buildings, gardens and features, and stipulates<br />

how the gardens are to be used and preserved.<br />

2.<br />

As-is plan of the palace gardens<br />

by Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell,<br />

178<strong>3.</strong><br />

29

2. The<br />

Title of the first guide to the<br />

gardens, compiled in 1809 by<br />

Johann Michael Zeyher (Photo:<br />

Palace Library Schwetzingen).<br />

30<br />

2. Description<br />

19th-Century: a Period of Dormancy<br />

Napoleon Bonaparte’s rearrangement of southwestern<br />

Germany in 1803 meant that the<br />

Electoral Palatinate east of the Rhine – which<br />

included Schwetzingen – fell to the House of<br />

Baden. Johann Michael Zeyher (1770-1843)<br />

was now responsible for the gardens in<br />

Schwetzingen, and one or two final alterations<br />

were carried out under his direction: in<br />

1804 he created an arboretum to the rear of<br />

the orangery, and in 1823-1824 he had the<br />

large rectangular basin at the west end of<br />

the gardens converted into a lake of natural<br />

appearance.<br />

The gardens had been opened to the public<br />

since around 1787 (this being the date of the<br />

first set of regulations for visitors to the site),<br />

and public interest in Schwetzingen remained<br />

high throughout the whole of the nineteenthcenturies.<br />

It is hardly surprising, then, to read in<br />

Zeyher’s first garden guide, published in<br />

1809: “No distinguished visitor has travelled<br />

through the area without tarrying in<br />

Schwetzingen; almost all princes, all the great<br />

and the famous have flocked to this German<br />

Versailles, this St. Cloud, this Aranjuez, for<br />

want of a better term for such a remarkable<br />

place.“ Friedrich Schiller, Joseph von<br />

Eichendorff and Ivan Turgeniev, to name just<br />

three renowned visitors, all thematised the<br />

palace gardens in their works.<br />

The huge interest enjoyed by Schwetzingen<br />

as a tourist destination throughout the<br />

nineteenth-century is further documented<br />

by the numerous engravings and countless<br />

guides to the gardens dating from this period.<br />

While the palace and gardens retained their<br />

eighteenth-century character, the town of<br />

Schwetzingen expanded as a result of latenineteenth-century<br />

industrialisation (in 1870<br />

Schwetzingen was linked to the Karlsruhe-<br />

Mannheim railway line); nevertheless,<br />

the Baroque features of the principal axis<br />

remained unaltered.<br />

Conservation and Maintenance in the<br />

20th-Century<br />

Interest in Schwetzingen remained high<br />

throughout the twentieth-century. Numerous<br />

articles published at the turn of the century<br />

in the journals Gartenkunst (Garden Design)<br />

and Gartenwelt (World of Gardens) bear<br />

witness to “the great significance of the<br />

gardens at Schwetzingen”, praising it as<br />

“the best-preserved gardens of post-Classical<br />

times“. Early interest in the heritage<br />

value of the gardens is borne out by the<br />

publication in 1933 of Kurt Martin’s seminal<br />

500-page work Die Kunstdenkmäler des<br />

Amtsbezirks Mannheim – Stadt Schwetzingen

(Monuments in the Administrative District<br />

of Mannheim: The Town of Schwetzingen).<br />

Major work was carried out on the palace<br />

theatre during this period, and it resumed<br />

business in the 1930s.<br />

Schwetzingen was spared major damage<br />

during the Second World War, with only<br />

a few individual buildings (including the<br />

railway station) bombed. The latter half of the<br />

twentieth-century saw the implementation of<br />

comprehensive measures designed to ensure<br />

preservation of the property. Buildings were<br />

meticulously restored; the statuary in the<br />

gardens was replaced with reproductions<br />

(the originals being moved to a permanent<br />

exhibition in the orangery); the palace was<br />

renovated (structural repairs to the main wing<br />

1975-1982; restoration of interior 1984-1991).<br />

The compilation of a management plan for<br />

the gardens was followed by a judicious<br />

programme of regeneration starting in 1970,<br />

whose aim it is to conserve the character<br />

intended by the original designers.<br />

The annual, two-month Schwetzingen<br />

Festival organised since 1952 by the regional<br />

broadcasting corporation Südwestrundfunk<br />

takes up the musical tradition of<br />

Schwetzingen’s summer-residence heyday,<br />

commissioning and staging contemporary<br />

opera in addition ot the established Baroque<br />

repertoire and thus continuing the tradition<br />

of patronage cultivated by Carl Theodor.<br />

With over 700 radio broadcasts every year,<br />

Schwetzingen Festival is the largest radio<br />

festival for classical music in the world.<br />

2. Description<br />

2.<br />

31

2.<br />

BATHHOUSE<br />

32<br />

Dr. Bärbel Pelker<br />

2. Description<br />

„ “<br />

… it is a place of mental and spiritual regeneration, one in which the ideas of the Enlightenment<br />

and of Freemasonry play an important part. Carl Theodor derived great pleasure<br />

from spending the afternoon hours in the bathhouse philosophising with scholars of both<br />

noble and common birth; contemporary sources attest principally to discussions on musical<br />

theory and musical aesthetics. It was in the room at the centre of the bathhouse that Carl<br />

Theodor himself tried his hand as a musician, playing the flute together with selected court<br />

musicians or travelling virtuosos with complete disregard for established social boundaries.

<strong>3.</strong> Justification for Inscription<br />

3 a)<br />

Criteria under which Inscription<br />

is Proposed (and Justification for<br />

Inscription under these Criteria)<br />

The title proposed in the tentative list, “Palace<br />

and Gardens at Schwetzingen”, has been<br />

altered and redefined in the course of the<br />

preparations for nomination of the property.<br />

The new title, “Schwetzingen: A Prince<br />

Elector’s Summer Residence”, takes account<br />

of Schwetzingen’s outstanding status as an<br />

example of an eighteenth-century summer<br />

residence on the one hand; on the other it still<br />

acknowledges the unique status of the garden,<br />

created within a clearly defined, specific time<br />

period and in close connection with this<br />

“summer residence” function and preserved<br />

in this identity as a monument. Moreover,<br />

the spatial layout of the garden embodies<br />

exceptional aspects of a past cultural tradition.<br />

Criterion (iii). Schwetzingen bears an exceptional<br />

testimony to a cultural tradition which<br />

has disappeared.<br />

Under the rule of Elector Carl Theodor of the<br />

Palatinate, Schwetzingen represents a classic<br />

example of the cultural phenomenon of a<br />

summer residence of the Enlightenment era<br />

and inspired by its ideas – ideas expressed<br />

by the iconography of the garden as much<br />

as by the Elector’s fostering of the sciences.<br />

The founding of the Palatinate Academy of<br />

the Sciences, the opening of the library to<br />

the public, the systematic investigation and<br />

documentation of archaeological history<br />

that was in its day unique in Germany,<br />

the founding of scientific institutions like<br />

the “Physics Cabinet”, the astronomical<br />

observatory or a meteorological measuring<br />

station, and the remarkably precise survey<br />

of the Palatinate conducted in Carl Theodor’s<br />

reign are all outstanding accomplishments in<br />

the spirit of an Enlightenment considered to<br />

place obligations on the ruler, too.<br />

With the focus increasingly on learned<br />

institutions, the nature and appearance of<br />

courtly display changed. The number of<br />

holidays and lavish festivities was reduced.<br />

On the numerous occasions when aristocratic<br />

visitors came to stay at the summer residence,<br />

formerly taken as welcome excuses for courtly<br />

pomp and circumstance, “the celebrations<br />

are now no longer ostentatious but tasteful<br />

and well chosen” (Schubart). It was in<br />

the field of courtly music in particular, a<br />

personal hobby of the Elector, that this new<br />

cultural seriousness found its expression:<br />

in the opportunity offered to all children<br />

of the Palatinate domains to attend a music<br />

school, the “Tonschule”; in its trailblazing<br />

for what was to become the culture of the<br />

modern orchestra; in the cultivation of opera<br />

at Schwetzingen, where up to four different<br />

operas per season were performed, each of<br />

them more than once.<br />

In this way the cultural traditions of the<br />

summer residence found their expression<br />

in music, in an extraordinary manner that<br />

was unique throughout Europe. There are<br />

a number of traits that are singular to the<br />

summer residence, with its court orchestra<br />

invariably present for six months every year:<br />

1. A unique circumstance within the culture of<br />

18th-century courtly music is the programmatic<br />

distinction, within the opera repertory, between<br />

the main and the summer residences. The<br />

Schwetzingen season was reserved for comic<br />

opera, performances in German, and subjects<br />

pertaining to the Enlightenment.<br />

In contrast to the formally celebrated<br />

Mannheim operas, magnificently performed<br />

on the name days of the Electoral couple<br />

with much courtly display, the summer stays<br />

at Schwetzingen were characterized not<br />

only by a programmatic difference in the<br />

music that was being played. There was also<br />

a typological variety unique by European<br />

standards (Opera buffa, Opéra comique and<br />

German “Singspiel”), an extraordinary number<br />

of new pieces, a progressive attitude towards<br />