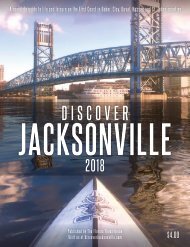

J Magazine Summer 2018

The magazine of the rebirth of Jacksonville's downtown

The magazine of the rebirth of Jacksonville's downtown

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ADDING UP<br />

THE VACANT<br />

DOWNTOWN<br />

BUILDINGS<br />

11<br />

Number<br />

of vacant<br />

buildings<br />

owned by<br />

the city.<br />

14<br />

Percentage<br />

of buildings<br />

that are<br />

vacant.<br />

62<br />

Percentage<br />

of buildings<br />

that are<br />

more than<br />

50 years old.<br />

73<br />

Number<br />

of vacant<br />

buildings.<br />

81<br />

Percentage<br />

of buildings<br />

locally<br />

owned.<br />

130<br />

Number<br />

of vacant<br />

areas<br />

owned by<br />

the city.<br />

160<br />

Number<br />

of acres<br />

of vacant<br />

land.<br />

more on how dilapidated Downtown really<br />

is,” said Ehas, a former chief administrative<br />

officer for the Duval County Property Appraiser’s<br />

Office. “It really is. It’s terrible.”<br />

Civic philanthropy<br />

can make a difference<br />

The Elena Flats building had been vacant<br />

for at least a decade when Meeks and<br />

Tredennick bought it in 2015. He believes it<br />

is one of two apartment buildings that were<br />

built in the decade after the Great Fire of<br />

1901.<br />

Meeks wasn’t looking for another renovation<br />

project, but Tredennick was concerned<br />

because the owner had sought a<br />

permit to tear it down. So the married couple<br />

began what Meeks calls a “love project,”<br />

restoring the building knowing they aren’t<br />

likely to recoup their investment.<br />

“We’ve lost so many old buildings Downtown,<br />

it was just a shame to see another one<br />

lost,” he said.<br />

Plus, he added, as vice chairman of the<br />

DIA, “I wanted to put my money where my<br />

mouth was.”<br />

Over the decades, the building at 122 E.<br />

Duval St. evolved from four spacious apartments<br />

to a rooming house with more than<br />

20 small units. The current renovation will<br />

return the building to a four-unit complex,<br />

with each two-bedroom apartment being<br />

about 2,000 square feet, including the front<br />

and back porches.<br />

Some developers believe the restrictions<br />

and guidelines tied to historic preservation<br />

projects are overly cumbersome. But Meeks<br />

disagrees.<br />

“If people have the right attitude going<br />

in, I think they’ll find them more of a help<br />

than a hindrance,” he said.<br />

Those guidelines also help protect the<br />

historic character in a neighborhood.<br />

Meeks knows restoring a historic building<br />

costs more — sometimes substantially<br />

more — than what it will be worth, based<br />

on current rent levels. That prevents most<br />

developers from taking on those types of<br />

projects.<br />

And he understands the city doesn’t<br />

have the money to fill every hole that exists<br />

in that differential.<br />

Meeks was hoping that gap could be<br />

partially filled by people in town with the<br />

resources to take on a project, seeing it as a<br />

source of civic philanthropy.<br />

But that hasn’t happened.<br />

In several cities, those efforts are successfully<br />

driven by nonprofits that help<br />

developers fill the financing gap through<br />

revolving loan funds donated by corporations.<br />

Discussions about that approach for<br />

Jacksonville began in 2014 with InvestJax,<br />

which hasn’t yet funded a project.<br />

What has worked<br />

in other cities<br />

Fifteen years ago, Cincinnati officials<br />

took the bold step of creating a nonprofit<br />

real estate development company to focus<br />

on revitalizing its dilapidated Central<br />

Business District and restoring an adjacent<br />

neighborhood once considered one of the<br />

most dangerous in the country.<br />

Cincinnati Center City Development<br />

Corp., known as 3CDC, soon took control of<br />

two private investment funds that provided<br />

loans to help bolster Downtown and distressed<br />

neighborhoods.<br />

It also received generous support from<br />

the city’s business community, including<br />

Procter & Gamble, Kroger, Fifth Third Bank<br />

and Western & Southern Financial Group.<br />

Each year since 3CDC was formed in<br />

2003, corporations have contributed $1.2<br />

million toward the nonprofit’s operating<br />

budget, said Joe Rudemiller, communications<br />

director for 3CDC.<br />

That amount covered the entire operating<br />

budget in 2003, when there were six to<br />

10 employees, he said. Now, as 3CDC has<br />

grown to 70 full-time staff members and 120<br />

seasonal temporary workers, the amount<br />

accounts for 15 percent of the operating<br />

budget. While 3CDC receives no taxpayer<br />

money for operating costs, it does receive<br />

government grants and loans on a project-by-project<br />

basis.<br />

In addition, corporations contributed<br />

$250 million for 3CDC to use as a revolving<br />

low-interest loan fund for projects.<br />

The results have been staggering, leading<br />

to an investment of more than $1.3 billion<br />

in Cincinnati’s Downtown and Overthe-Rhine<br />

neighborhood. The first major<br />

project was completed in 2006, just three<br />

years after 3CDC began.<br />

Rudemiller said the nonprofit’s work has<br />

The exterior of the Elena Flats building during its renovation into its original four-unit complex.<br />

CONTINUED ON PAGE 96<br />

SUMMER <strong>2018</strong> | J MAGAZINE 79