Aziz Art August 2018

https://issuu.com/home/docs/aziz_art_august_2018/edit/links

https://issuu.com/home/docs/aziz_art_august_2018/edit/links

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

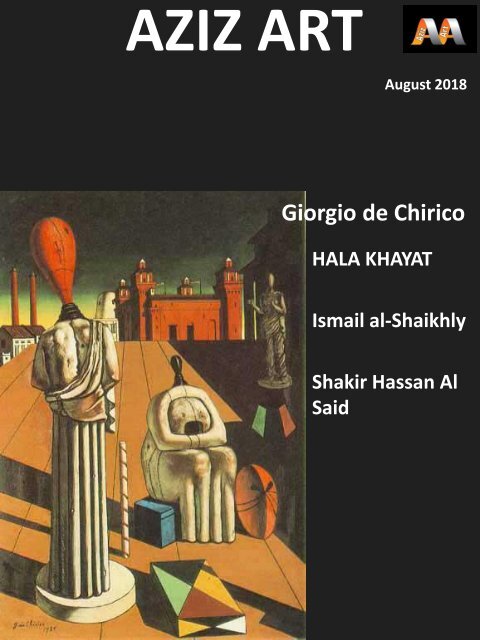

AZIZ ART<br />

<strong>August</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

Giorgio de Chirico<br />

HALA KHAYAT<br />

Ismail al-Shaikhly<br />

Shakir Hassan Al<br />

Said

1-Giorgio de Chirico<br />

11-Hala Khayat<br />

13-Ismail al-Shaikhly<br />

19-Shakir Hassan Al Said<br />

Director: <strong>Aziz</strong> Anzabi<br />

Editor : Nafiseh Yaghoubi<br />

Translator : Asra Yaghoubi<br />

Research: Zohreh Nazari<br />

http://www.aziz_anzabi.com

Giorgio de Chirico<br />

10 July 1888 – 20 November 1978<br />

was an Italian artist and writer. In<br />

the years before World War I, he<br />

founded the scuola metafisica art<br />

movement, which profoundly<br />

influenced the surrealists. After<br />

1919, he became interested in<br />

traditional painting techniques,<br />

and worked in a neoclassical or<br />

neo-Baroque style, while<br />

frequently revisiting the<br />

metaphysical themes of his earlier<br />

work.<br />

Life and works<br />

De Chirico was born in Volos,<br />

Greece, to a Genoan mother and a<br />

Sicilian father.[After studying art at<br />

Athens Polytechnic—mainly under<br />

the guidance of the influential<br />

Greek painters Georgios Roilos<br />

and Georgios Jakobides—and<br />

Florence, he moved to Germany in<br />

1906, following his father's death<br />

in 1905. He entered the Academy<br />

of Fine <strong>Art</strong>s in Munich, where he<br />

studied under Max Klinger and<br />

read the writings of the<br />

philosophers Nietzsche, <strong>Art</strong>hur<br />

Schopenhauer and Otto<br />

Weininger. There, he also studied<br />

the works of Arnold Böcklin.<br />

He returned to Italy in the summer<br />

of 1909 and spent six months in<br />

Milan. At the beginning of 1910, he<br />

moved to Florence where he<br />

painted the first of his<br />

'Metaphysical Town Square' series,<br />

The Enigma of an Autumn<br />

Afternoon, after the revelation he<br />

felt in Piazza Santa Croce. He also<br />

painted The Enigma of the Oracle<br />

while in Florence. In July 1911 he<br />

spent a few days in Turin on his way<br />

to Paris. De Chirico was profoundly<br />

moved by what he called the<br />

'metaphysical aspect' of Turin,<br />

especially the architecture of its<br />

archways and piazzas. De Chirico<br />

moved to Paris in July 1911, where<br />

he joined his brother Andrea.<br />

Through his brother he met Pierre<br />

Laprade, a member of the jury at<br />

the Salon d'Automne, where he<br />

exhibited three of his works:<br />

Enigma of the Oracle, Enigma of an<br />

Afternoon and Self-Portrait. During<br />

1913 he exhibited paintings at the<br />

Salon des Indépendants and Salon<br />

d’Automne; his work was noticed<br />

by Pablo Picasso and Guillaume<br />

Apollinaire, and he sold his first<br />

painting, The Red Tower. In 1914,<br />

through Apollinaire, he met the art<br />

1

dealer Paul Guillaume, with whom<br />

he signed a contract for his artistic<br />

output.<br />

At the outbreak of World War I,<br />

he returned to Italy. Upon his<br />

arrival in May 1915, he enlisted in<br />

the army, but he was considered<br />

unfit for work and assigned to the<br />

hospital at Ferrara. Here he met<br />

with Carlo Carrà and together they<br />

founded the pittura metafisica<br />

movement.[2] He continued to<br />

paint, and in 1918, he transferred<br />

to Rome. Starting from 1918, his<br />

work was exhibited extensively in<br />

Europe.<br />

De Chirico is best known for the<br />

paintings he produced between<br />

1909 and 1919, his metaphysical<br />

period, which are characterized<br />

by haunted, brooding moods<br />

evoked by their images. At the<br />

start of<br />

this period, his subjects were still<br />

cityscapes inspired by the bright<br />

daylight of Mediterranean cities,<br />

but gradually he turned his<br />

attention to studies of cluttered<br />

storerooms, sometimes inhabited<br />

by mannequin-like hybrid figures.<br />

In autumn, 1919, de Chirico<br />

published an article in Valori plastici<br />

entitled "The Return of<br />

Craftsmanship", in which he<br />

advocated a return to traditional<br />

methods and iconography.This<br />

article heralded an abrupt change<br />

in his artistic orientation, as he<br />

adopted a classicizing manner<br />

inspired by such old masters as<br />

Raphael and Signorelli, and became<br />

an outspoken opponent of modern<br />

art.<br />

In the early 1920s, the Surrealist<br />

writer André Breton discovered one<br />

of de Chirico's metaphysical<br />

paintings on display in Guillaume's<br />

Paris gallery, and was<br />

enthralled.Numerous young artists<br />

who were similarly affected by de<br />

Chirico's imagery became the core<br />

of the Paris Surrealist group<br />

centered around Breton. In 1924 de<br />

Chirico visited Paris and was<br />

accepted into the group, although<br />

the surrealists were severely critical<br />

of his post-metaphysical work.

De Chirico met and married his<br />

first wife, the Russian ballerina<br />

Raissa Gurievich in 1925, and<br />

together they moved to Paris.His<br />

relationship with the Surrealists<br />

grew increasingly contentious, as<br />

they publicly disparaged his new<br />

work; by 1926 he had come to<br />

regard them as "cretinous and<br />

hostile".They soon parted ways in<br />

acrimony. In 1928 he held his first<br />

exhibition in New York City and<br />

shortly afterwards, London. He<br />

wrote essays on art and other<br />

subjects, and in 1929 published a<br />

novel entitled Hebdomeros, the<br />

Metaphysician. Also in 1929, he<br />

made stage designs for Sergei<br />

Diaghilev.<br />

De Chirico in 1970,<br />

photographed by Paolo Monti.<br />

Fondo Paolo Monti, BEIC<br />

In 1930, de Chirico met his<br />

second wife, Isabella Pakszwer Far,<br />

a Russian, with whom he would<br />

remain for the rest of his life.<br />

Together they moved to Italy in<br />

1932 and to the US in 1936,[2]<br />

finally settling in Rome in 1944.<br />

In 1948 he bought a house<br />

near the Spanish Steps which is<br />

now a museum dedicated to his<br />

work.<br />

In 1939, he adopted a neo-Baroque<br />

style influenced by Rubens.De<br />

Chirico's later paintings never<br />

received the same critical praise as<br />

did those from his metaphysical<br />

period. He resented this, as he<br />

thought his later work was better<br />

and more mature. He nevertheless<br />

produced backdated "selfforgeries"<br />

both to profit from his<br />

earlier success, and as an act of<br />

revenge—retribution for the critical<br />

preference for his early work.He<br />

also denounced many paintings<br />

attributed to him in public and<br />

private collections as forgeries. In<br />

1945, he published his memoirs.<br />

He remained extremely prolific<br />

even as he approached his 90th<br />

year. During the 1960s,<br />

Massimiliano Fuksas worked in his<br />

atelier. In 1974 de Chirico was<br />

elected to the French Académie des<br />

Beaux-<strong>Art</strong>s. He died in Rome on 20<br />

November 1978.<br />

His brother, Andrea de Chirico, who<br />

became famous under the name<br />

Alberto Savinio, was also a writer<br />

and a painter.

Style<br />

In the paintings of his<br />

metaphysical period, de Chirico<br />

developed a repertoire of<br />

motifs—empty arcades, towers,<br />

elongated shadows, mannequins,<br />

and trains among others—that he<br />

arranged to create "images of<br />

forlornness and emptiness" that<br />

paradoxically also convey a feeling<br />

of "power and freedom<br />

".According to Sanford<br />

Schwartz, de Chirico—whose<br />

father was a railroad engineer—<br />

painted images that suggest "the<br />

way you take in buildings and<br />

vistas from the perspective of a<br />

train window. His towers, walls,<br />

and plazas seem to flash by, and<br />

you are made to feel the power<br />

that comes from seeing things<br />

that way: you feel you know them<br />

more intimately than the people<br />

do who live with them day by day."<br />

In 1982, Robert Hughes wrote<br />

that de Chirico<br />

could condense voluminous feeling<br />

through metaphor<br />

and association ... In The Joy of<br />

Return, 1915, de Chirico's train has<br />

once more entered the city ... a<br />

bright ball of vapor hovers directly<br />

above its smokestack. Perhaps it<br />

comes from the train and is near<br />

us. Or possibly it is a cloud on the<br />

horizon, lit by the sun that never<br />

penetrates the buildings, in the last<br />

electric blue silence of dusk. It<br />

contracts the near and the far,<br />

enchanting one's sense of space.<br />

Early de Chiricos are full of such<br />

effects. Et quid amabo nisi quod<br />

aenigma est? ("What shall I love if<br />

not the enigma?")—this question,<br />

inscribed by the young artist on his<br />

self-portrait in 1911, is their<br />

subtext.<br />

In this, he resembles his more<br />

representational American<br />

contemporary, Edward Hopper:<br />

their pictures' low sunlight, their<br />

deep and often irrational shadows,<br />

their empty walkways and<br />

portentous silences creating an<br />

enigmatic visual poetry.

legacy<br />

De Chirico won praise for his work<br />

almost immediately from the<br />

writer Guillaume Apollinaire, who<br />

helped to introduce his work to<br />

the later Surrealists. De Chirico<br />

strongly influenced the Surrealist<br />

movement: Yves Tanguy wrote<br />

how one day in 1922 he saw one<br />

of de Chirico's paintings in an art<br />

dealer's window, and was so<br />

impressed by it he resolved on the<br />

spot to become an<br />

artist—although he had never<br />

even held a brush. Other<br />

Surrealists who acknowledged de<br />

Chirico's influence include Max<br />

Ernst, Salvador Dalí, and René<br />

Magritte. Other artists as diverse<br />

as Giorgio Morandi, Carlo Carrà,<br />

Paul Delvaux, Carel Willink, Harue<br />

Koga and Philip Guston were<br />

influenced by de Chirico.<br />

De Chirico's style has influenced<br />

several filmmakers, particularly in<br />

the 1950s through 1970s. The<br />

visual style of the French animated<br />

film Le Roi et l'oiseau, by Paul<br />

Grimault and Jacques Prévert, was<br />

influenced by de Chirico's work,<br />

primarily via Tanguy, a friend of<br />

Prévert. The visual style of Valerio<br />

Zurlini's film The Desert of the<br />

Tartars (1976) was influenced by de<br />

Chirico's work. Michelangelo<br />

Antonioni, the Italian film director,<br />

also claimed to be influenced by de<br />

Chirico. Some comparison can be<br />

made to the long takes in<br />

Antonioni's films from the 1960s, in<br />

which the camera continues to<br />

linger on desolate cityscapes<br />

populated by a few distant figures,<br />

or none at all, in the absence of the<br />

film's protagonists.<br />

Writers who have appreciated de<br />

Chirico include John Ashbery, who<br />

has called Hebdomeros<br />

"probably...the finest [major work<br />

of Surrealist fiction]."Several of<br />

Sylvia Plath's poems are influenced<br />

by de Chirico. In his book Blizzard of<br />

One Mark Strand included a poetic<br />

diptych called "Two de Chiricos:"<br />

"The Philosopher's Conquest" and<br />

"The Disquieting Muses."<br />

Gabriele Tinti has composed three<br />

poemsinspired by Giorgio de<br />

Chirico’s paintings; The Nostalgia of<br />

the poet (1914),The Uncertainty of<br />

the Poet (1913) and Ariadne<br />

(1913),respectively in the<br />

collections of Peggy Guggenheim<br />

Collection.

Tate and Metropolitan Museum of <strong>Art</strong>. The poems were read by actor<br />

Burt Young at The Met in New York<br />

The box art for Fumito Ueda's PlayStation 2 game Ico used in Japan and<br />

Europe was strongly influenced by de Chirico.The cover art of New<br />

Order's single "Thieves Like Us" is based on de Chirico's painting The<br />

Evil Genius of a King.<br />

Honours<br />

1958: Member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine <strong>Art</strong>s<br />

of Belgium.<br />

Academie de France.

Selected works<br />

Flight of the Centauri, Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon and Enigma of<br />

the Oracle (1909)<br />

Ritratto di Andrea de Chirico (Alias Alberto Savinio) (1909–1910)<br />

The Enigma of the Hour (1911)<br />

The Nostalgia of the Infinite (1911), or 1912–1913<br />

Melanconia, The Enigma of the Arrival and La Matinée Angoissante<br />

(1912)<br />

The Soothsayers Recompense, The Red Tower, Ariadne, The Awakening<br />

of Ariadne, The Uncertainty of the Poet, La Statua Silenziosa, The<br />

Anxious Journey, Melancholy of a Beautiful Day, Le Rêve Transformé,<br />

and Self-Portrait (1913)<br />

The Anguish of Departure (begun in 1913), Portrait of Guillaume<br />

Apollinaire, The Nostalgia of the Poet, L'Énigme de la fatalité, Gare<br />

Montparnasse (The Melancholy of Departure), The Song of Love, The<br />

Enigma of a Day, The Philosopher's Conquest, The Child's Brain, The<br />

Philosopher and the Poet, Still Life: Turin in Spring, Piazza d'Italia<br />

(Autumn Melancholy), and Melancholy and Mystery of a Street (1914)<br />

The Evil Genius of a King (begun in 1914), The Seer (or The Prophet),<br />

Piazza d’Italia, The Double Dream of Spring, The Purity of a Dream, Two<br />

Sisters (The Jewish Angel) and The Duo (1915)<br />

Andromache, The Melancholy of Departure, The Disquieting Muses,<br />

Metaphysical Interior with Biscuits (1916)<br />

Metaphysical Interior with Large Factory and The Faithful Servitor (both<br />

began in 1916), The Great Metaphysician, Ettore e Andromaca,<br />

Metaphysical Interior, Geometric Composition with Landscape and<br />

Factory and Great Metaphysical Interior (1917)<br />

Metaphysical Muses and Hermetic Melancholy (1918)<br />

Still Life with Salami and The Sacred Fish (1919)<br />

Self-portrait (1920)<br />

The Disquieting Muses (1947), replica of the 1916 painting, University<br />

of Iowa Museum of <strong>Art</strong>

Italian Piazza, Maschere and Departure of the Argonauts (1921)<br />

The Prodigal Son (1922)<br />

Florentine Still Life (c. 1923)<br />

The House with the Green Shutters (1924)<br />

The Great Machine (1925) Honolulu Museum of <strong>Art</strong><br />

Au Bord de la Mer, Le Grand Automate, The Terrible Games,<br />

Mannequins on the Seashore and The Painter (1925)<br />

La Commedia e la Tragedia (Commedia Romana), The Painter's Family<br />

and Cupboards in a Valley (1926)<br />

L’Esprit de Domination, The Eventuality of Destiny (Monumental<br />

Figures), Mobili nella valle and The Archaeologists (1927)<br />

Temple et Forêt dans la Chambre (1928)<br />

Gladiatori (began in 1927), The Archaeologists IV (from the series<br />

Metamorphosis), The return of the Prodigal son I (from the series<br />

Metamorphosis) and Bagnante (Ritratto di Raissa) (1929)<br />

I fuochi sacri (for the Calligrammes) 1929<br />

Illustrations from the book Calligrammes by Guillaume Apollinaire<br />

(1930)<br />

I Gladiatori (Combattimento) (1931)<br />

Milan Cathedral, 1932<br />

Cavalos a Beira-Mar (1932–1933)<br />

Cavalli in Riva al Mare (1934)<br />

La Vasca di Bagni Misteriosi (1936)<br />

The Vexations of The Thinker (1937)<br />

Self-portrait (1935–1937)<br />

Archeologi (1940)<br />

Illustrations from the book L’Apocalisse (1941)<br />

Portrait of Clarice Lispector (1945)<br />

Villa Medici – Temple and Statue (1945)<br />

Minerva (1947)<br />

Metaphysical Interior with Workshop (1948)<br />

Venecia, Puente de Rialto<br />

Fiat (1950)

Piazza d'Italia (1952)<br />

The Fall – Via Crucis (1947–54)<br />

Venezia, Isola di San Giorgio (1955)<br />

Salambò su un cavallo impennato (1956)<br />

Metaphysical Interior with Biscuits (1958)<br />

Piazza d'Italia (1962)<br />

Cornipedes, (1963)<br />

La mia mano sinistra, (1963), Chianciano Museum of <strong>Art</strong><br />

Manichino (1964)<br />

Ettore e Andromaca (1966)<br />

The Return of Ulysses, Interno Metafisico con Nudo Anatomico and<br />

Mysterious Baths – Flight Toward the Sea (1968)<br />

Il rimorso di Oreste, La Biga Invincibile and Solitudine della Gente di<br />

Circo (1969)<br />

Orfeo Trovatore Stanco, Intero Metafisico and Muse with Broken<br />

Column (1970)<br />

Metaphysical Interior with Setting Sun (1971)<br />

Sole sul cavalletto (1973)<br />

Mobili e rocce in una stanza, La Mattina ai Bagni misteriosi, Piazza<br />

d'Italia con Statua Equestre, La mattina ai bagni misteriosi and Ettore e<br />

Andromaca (1973)<br />

Pianto d'amore – Ettore e Andromaca and The Sailors' Barracks (1974)

HALA KHAYAT<br />

Hala Khayat is the Head of Sales<br />

at Christie's Middle East. She has a<br />

BA in Fine <strong>Art</strong>s & Visual<br />

Communications from the<br />

University of Damascus, Syria and<br />

an MA in Design Studies from<br />

Central St Martin's College of <strong>Art</strong> &<br />

Design, London. She has held a<br />

variety of roles in the world of art<br />

and journalism, including working<br />

as an <strong>Art</strong> Consultant for galleries in<br />

Damascus. She is a regular speaker<br />

on the history of Arab art and the<br />

Middle Eastern <strong>Art</strong> Market.<br />

It is not often that a private<br />

collection dedicates itself entirely<br />

to providing a full overview of<br />

almost a century of art from one<br />

region. However, during many long<br />

years living in the United Kingdom,<br />

Syrian-British couple Rona and<br />

Walid Jalanbo viewed art collecting<br />

as a natural link back to their<br />

heritage and culture.<br />

When the Jalanbos began<br />

acquiring art some 30 years ago,<br />

they did so with a view that Middle<br />

Eastern art - particularly that from<br />

Syria - was beautiful, rich in<br />

diversity, and lacking basic support<br />

from the international art world.<br />

From early on, Rona and Walid<br />

were devoted patrons of<br />

contemporary art from the region,<br />

encouraging many young artists<br />

early in their careers with a buying<br />

power that enabled them to<br />

continue to plan exhibitions and<br />

create. All works were bought with<br />

an insightful curatorial eye – they<br />

meshed important modern art<br />

pieces with pieces from the<br />

developing contemporary art<br />

scene.<br />

11

The more I got to know and work<br />

with the Jalanbos, the more I saw<br />

that they were choosing works<br />

with a larger vision of eventually<br />

setting up a public art foundation.<br />

The idea was that this space<br />

would one day develop into a<br />

creative hub for all young<br />

enthusiasts to come, share<br />

ideas, and take inspiration from<br />

the works on display. The plans<br />

and location for the creative<br />

space were in order but were<br />

sadly halted when the Syrian<br />

conflict began in 2011. Until that<br />

point, the collection had only been<br />

on view privately in the homes of<br />

Rona and Walid. It was then that<br />

their son, Khaled, took the<br />

initiative to archive and<br />

document the collection and<br />

replace the plans for the physical<br />

domain with this website.<br />

The importance of a collection of<br />

this scale going public cannot be<br />

overstated. Not only is it<br />

unearthing modern Middle Eastern<br />

masterpieces by artists such as<br />

Chaura, Moudarres, Kayyali and<br />

Yagan that have never been<br />

publically viewed before, but it is<br />

also shedding light on<br />

contemporary and emerging artists<br />

from our region and increasing<br />

their reach. This is a tremendously<br />

exciting project for everyone in the<br />

Middle Eastern art world,<br />

particularly given the educational<br />

and forward-thinking direction it is<br />

taking.

Ismail al-Shaikhly<br />

is considered an early pioneer of<br />

Iraqi modern art. He developed a<br />

unique style that resulted from a<br />

diverse set of influences. His<br />

mature works are instantly<br />

recognizable for their abstracted<br />

human figures, vibrant color<br />

combinations, and obscured<br />

backgrounds. However,<br />

there were many iterations of al-<br />

Shaikhly's favored subject matter,<br />

Iraqi village life, over the course of<br />

his career. Like others of his<br />

generation of artists, al-Shaikhly<br />

was a versatile painter who<br />

experimented with various modes<br />

of representation. As a result, his<br />

oeuvre exhibits a range of stylistic<br />

references and negotiations.<br />

Al-Shaikhly was educated at the<br />

Institute of Fine <strong>Art</strong> in Baghdad<br />

and was a member of the first<br />

graduating class of 1945. At the<br />

institute, the artist studied under<br />

Faiq Hassan, one of the leading<br />

figures in the Iraqi art world, and<br />

was his most gifted student. After<br />

graduating, al-Shaikhly became its<br />

first alumnus to study abroad,<br />

attending the École Nationale<br />

Supérieure des Beaux-<strong>Art</strong>s in Paris<br />

in 1951. He returned to Baghdad<br />

and was an influential member of<br />

the Pioneers Group, an artist<br />

society founded by Faiq Hassan. He<br />

became the group's leader in 1962<br />

after Hassan stepped down. Al-<br />

Shaikhly was also a founding<br />

member of the Society of Iraqi<br />

Plastic <strong>Art</strong>ists and joined the Iraqi<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ist Society. Professionally, his<br />

most distinguished position was as<br />

the director general of the<br />

Directorate of Plastic <strong>Art</strong>s in<br />

Baghdad.<br />

Al-Shaikhly's early work reflects the<br />

influence of his mentor, Faiq<br />

Hassan, and the artistic production<br />

of these two painters has often<br />

been compared. Indeed, there are<br />

striking similarities between the<br />

work of the master and pupil. They<br />

both favored the Iraqi countryside<br />

and village life as subject matter.<br />

Likewise, the quaint,<br />

impressionistic treatment of people<br />

and nature in each of their<br />

canvases hints at a close didactic<br />

relationship between the artists.<br />

However, this resemblance<br />

characterizes an early period in al-<br />

Shaikhly's career,<br />

13

after which he would venture out<br />

into his own artistic realm. His<br />

mature style is abstract,<br />

demonstrating the artist's interest<br />

in form and color at the willing<br />

expense of narrative but not<br />

subject matter.<br />

Women figure prominently as a<br />

central theme in al-Shaikhly's<br />

work. Throughout his various<br />

experiments with representations,<br />

he remained faithful to the<br />

feminine form. He seems to have<br />

been interested in the exploration<br />

of a singular subject, perhaps<br />

desiring to unleash its aesthetic<br />

potential. It is significant that he<br />

selected a subject that has<br />

occupied artistic expression since<br />

the daybreak of humanity, the<br />

female body.<br />

Oftentimes painting them in<br />

groupings, the artist's females<br />

gaze out at the viewer with<br />

pointed stares. Simplified with<br />

oval faces and generic bodies,<br />

they seem to be in various states<br />

of coming and going: to the<br />

mosque, to the souq, to some<br />

domestic chore. Yet they pause for<br />

the painter to capture their<br />

individual attitudes along with their<br />

homogenous shapes. There is a<br />

rhythm implied in the repetition of<br />

ovals, squares, and strong curved<br />

lines that reflects the pace of the<br />

women's daily lives, as well as the<br />

artist's interest in patterning within<br />

the Islamic ornamental tradition.<br />

In the artist's more iconic paintings,<br />

produced in the last two decades of<br />

the twentieth century, the female<br />

groups move in and out of a fading<br />

background. His subjects seem to<br />

be wanderers in a hazy landscape,<br />

sometimes dotted with triangular<br />

shapes hinting at tent structures<br />

and sometimes obscured<br />

altogether. The women in these<br />

later works occupy huddled spaces,<br />

identifiable only by the Iraqi abaya<br />

draped over their bodies. Color<br />

occupies a premier place in each of<br />

these canvases as he reduces his<br />

figures to flesh-colored circles,<br />

bright rectangular bodies, and black<br />

coverings. These expressions are<br />

filled with kinetic energy. By virtue<br />

of the hurried brushstrokes and<br />

color highlights, the feminine forms<br />

seem to vibrate even as the<br />

background fades.

Al-Shaikhly exhibited his work<br />

prodigiously throughout the<br />

world. He actively participated in<br />

Baghdadi exhibitions by the<br />

Pioneers and other artist<br />

organizations in which he was a<br />

part. Thus his work was highly<br />

visible domestically.<br />

Al-Shaikhly was also a part of<br />

several group exhibitions abroad<br />

and his work was displayed<br />

in cities like Paris, London,<br />

Ankara, Belgrade, Madrid, Jakarta,<br />

and Delhi.<br />

In 1955 and 1958, al-Shaikhly's<br />

artwork toured counties like China,<br />

Russia, Bulgaria, Poland, and India.<br />

The artist's paintings were also<br />

widely appreciated in the Arab<br />

world as he exhibited in almost<br />

every Arab capital. Al-Shaikhly's<br />

works are held in the collections of<br />

Mathaf: The Arab Museum of<br />

Modern <strong>Art</strong> in Doha, Qatar and at<br />

the Jordan National Gallery of Fine<br />

<strong>Art</strong> in Amman.<br />

Exhibitions<br />

1976 Against Discrimination, Baghdad, Iraq<br />

1974 Arab Biennial, Baghdad, Iraq<br />

1958 Contemporary Iraqi <strong>Art</strong> Tour: China, Russia, Bulgaria, Poland,<br />

former Yugoslavia<br />

1955 Contemporary Iraqi <strong>Art</strong> Tour: India<br />

1954 - 1956 Al-Mansour Club, Baghdad, Iraq<br />

1953 Exhibition in Alexandria, Egypt<br />

1952 All 22 exhibitions of the Pioneers, National Museum of<br />

Modern <strong>Art</strong>, Al-Riwaq Gallery, and the Institute of Fine <strong>Art</strong>, Baghdad,<br />

Iraq<br />

_____ Exhibition in Beirut, Lebanon<br />

1946 Exhibition of the Society of the Friends of <strong>Art</strong>, Baghdad, Iraq

Shakir Hassan Al Said (1925–<br />

2004), an Iraqi painter, sculptor<br />

and writer, is considered one of<br />

Iraq's most innovative and<br />

influential artists. An artist,<br />

philosopher, art critic and art<br />

historian, he was actively involved<br />

in the formation of two important<br />

art groups that influenced the<br />

direction of post-colonial art in<br />

Iraq. He, and the art groups in<br />

which he was involved,<br />

shaped the modern Iraqi art<br />

movement and bridged the gap<br />

between modernity and heritage.<br />

His theories charted a new Arabic<br />

art aesthetic which allowed for<br />

valuations of regional art through<br />

lenses that were uniquely Arabic<br />

rather than Western.<br />

Biography<br />

Al Said was born in Samawa,<br />

Iraq; a rural area. He spent most<br />

of his adult life living and working<br />

in Bagdad.His rural upbringing<br />

was an important source of<br />

inspiration for his art and his<br />

philosophies. He wrote about his<br />

daily trek to school in the<br />

following terms:<br />

"On my way from school, I used to<br />

see scores of faces, brown faces,<br />

painful and toiling faces. How close<br />

they were to my heart! They<br />

pressed me and I passed them<br />

again and again. They suffered and I<br />

felt their suffering. The peasants<br />

with their loose belts were pricked<br />

by thorns. They were so close to my<br />

heart!"<br />

In 1948, he received a degree in<br />

social science from the Higher<br />

Institute of Teachers in Baghdad<br />

and in 1954, a diploma in painting<br />

from the Institute of Fine <strong>Art</strong>s in<br />

Baghdad where he was taught by<br />

Jawad Saleem.He continued his<br />

studies at the École nationale<br />

supérieure des Beaux-<strong>Art</strong>s in Paris<br />

until 1959,where he was taught by<br />

Raymond Legueult.[8] During his<br />

stay in Paris, he discovered Western<br />

modern art in galleries and<br />

Sumerian art at the Louvre.After his<br />

return to Baghdad in 1959, Al Said<br />

studied the work of Yahya ibn<br />

Mahmud al-Wasiti,sufismand<br />

Mansur Al-Hallaj.He gradually<br />

abandoned figurative expressions<br />

and centered his compositions on<br />

Arabic calligraphy.<br />

19

With Jawad Saleem,<br />

he co-founded Jama'et<br />

Baghdad lil Fann al-Hadith<br />

(Baghdad Modern <strong>Art</strong> Group) in<br />

1951; one of the most unusual<br />

arts movements in the<br />

Middle East in the post–World<br />

War II,that aimed to achieve an<br />

artistic approach both modern<br />

and embracing of tradition.This<br />

specific approach was called<br />

Istilham al-turath (Seeking<br />

inspiration from tradition),<br />

considered as "the basic point of<br />

departure, to achieve through<br />

modern styles, a cultural<br />

vision".These artists were inspired<br />

by the 13th-century Baghdad<br />

School and the work of<br />

calligraphers and illustrators such<br />

as Yahya Al-Wasiti who was active<br />

in Baghdad in the 1230s. They<br />

believed that the Mongol invasion<br />

of 1258 represented a "break in<br />

the chain of pictorial Iraqi art"<br />

and wanted to recover lost<br />

traditions.After the death of<br />

Saleem in 1961, al-Said headed<br />

the group.<br />

Al Said wrote the manifesto for the<br />

Baghdad Modern <strong>Art</strong> Group and<br />

read it at the group's first<br />

exhibition in 1951. It was the<br />

first art manifesto to be published<br />

in Iraq. Scholars often consider this<br />

event to the birth of the Iraqi<br />

modern art movement.<br />

Al Said also wrote the manifesto for<br />

an art group he founded in 1971.<br />

After suffering from a spiritual<br />

crisis, the artist broke away from<br />

the Baghdad Modern <strong>Art</strong> group and<br />

formed the Al Bu'd al Wahad (or<br />

the One Dimension Group)", which<br />

was deeply infused with Al Said's<br />

theories about the place of art in<br />

nationalism.The objectives of the<br />

One Dimension Group were multidimensional<br />

and complex. At the<br />

most basic level, the group rejected<br />

two and three-two dimensional<br />

artwork in favour of a single "inner<br />

dimension". In practice, a single<br />

inner dimension was difficult to<br />

manifest because most artworks<br />

are produced on two-dimensional<br />

surfaces. At a more profound level,<br />

"one dimension" refers to<br />

"eternity". Al Said explained:<br />

"From a philosophical point of view,<br />

the One-Dimension is eternity, or<br />

an extension of the past to the time<br />

before the existence of pictorial<br />

surface; to the non-surface.

Our consciousness of the world is a<br />

relative presence. It is our selfexistence<br />

while our absence is our<br />

eternal presence."<br />

Al Said actively searched for<br />

relationships between time and<br />

space; and for a visual language<br />

that would connect Iraq's deep art<br />

traditions with modern art<br />

methods and materials. The<br />

incorporation of callij (calligraphy)<br />

letters into modern artworks was<br />

an important aspect of this. The<br />

letter became part of Al Said's<br />

transition from figurative art to<br />

abstract art. Arabic calligraphy<br />

was charged with intellectual and<br />

esoteric Sufi meaning, in that it<br />

was an explicit reference to a<br />

Medieval theology where letters<br />

were seen as primordial signifiers<br />

and manipulators of the cosmos.<br />

This group was part of a broader<br />

Islamic art movement that<br />

emerged independently across<br />

North Africa and parts of Asia in the<br />

1950s and known as the hurufiyah<br />

art movement. Hurufiyah refers to<br />

the attempt by artists to combine<br />

traditional art forms, notably<br />

calligraphy as a graphic element<br />

within a contemporary<br />

artwork.Hurufiyah artists rejected<br />

Western art concepts, and instead<br />

searched for a new visual languages<br />

that reflected their own culture and<br />

heritage. These artists successfully<br />

transformed calligraphy into a<br />

modern aesthetic, which was both<br />

contemporary and indigenous.<br />

Al Said, used his writing, lectures<br />

and his involvement in various art<br />

groups to shape the direction of<br />

the modern Iraqi art movement<br />

and bridged the gap between<br />

modernity and heritage.In so doing,<br />

Al Said "charted a new Arabo-<br />

Islamic art aesthetic, and thus<br />

initiated a possible alternative for<br />

art valuating for local and regional<br />

art other than those allowed<br />

through an exclusionary Western<br />

canon of art history."

http://www.aziz_anzabi.com