BCJ_SUMMER17 Digital Edition

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

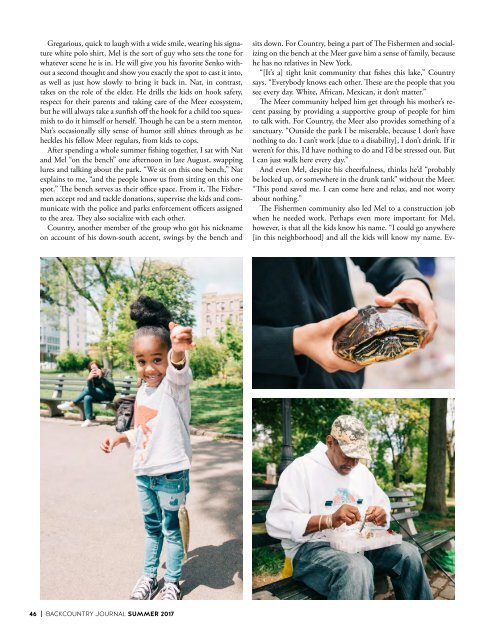

Gregarious, quick to laugh with a wide smile, wearing his signature<br />

white polo shirt, Mel is the sort of guy who sets the tone for<br />

whatever scene he is in. He will give you his favorite Senko without<br />

a second thought and show you exactly the spot to cast it into,<br />

as well as just how slowly to bring it back in. Nat, in contrast,<br />

takes on the role of the elder. He drills the kids on hook safety,<br />

respect for their parents and taking care of the Meer ecosystem,<br />

but he will always take a sunfish off the hook for a child too squeamish<br />

to do it himself or herself. Though he can be a stern mentor,<br />

Nat’s occasionally silly sense of humor still shines through as he<br />

heckles his fellow Meer regulars, from kids to cops.<br />

After spending a whole summer fishing together, I sat with Nat<br />

and Mel “on the bench” one afternoon in late August, swapping<br />

lures and talking about the park. “We sit on this one bench,” Nat<br />

explains to me, “and the people know us from sitting on this one<br />

spot.” The bench serves as their office space. From it, The Fishermen<br />

accept rod and tackle donations, supervise the kids and communicate<br />

with the police and parks enforcement officers assigned<br />

to the area. They also socialize with each other.<br />

Country, another member of the group who got his nickname<br />

on account of his down-south accent, swings by the bench and<br />

sits down. For Country, being a part of The Fishermen and socializing<br />

on the bench at the Meer gave him a sense of family, because<br />

he has no relatives in New York.<br />

“[It’s a] tight knit community that fishes this lake,” Country<br />

says. “Everybody knows each other. These are the people that you<br />

see every day. White, African, Mexican, it don’t matter.”<br />

The Meer community helped him get through his mother’s recent<br />

passing by providing a supportive group of people for him<br />

to talk with. For Country, the Meer also provides something of a<br />

sanctuary. “Outside the park I be miserable, because I don’t have<br />

nothing to do. I can’t work [due to a disability], I don’t drink. If it<br />

weren’t for this, I’d have nothing to do and I’d be stressed out. But<br />

I can just walk here every day.”<br />

And even Mel, despite his cheerfulness, thinks he’d “probably<br />

be locked up, or somewhere in the drunk tank” without the Meer.<br />

“This pond saved me. I can come here and relax, and not worry<br />

about nothing.”<br />

The Fishermen community also led Mel to a construction job<br />

when he needed work. Perhaps even more important for Mel,<br />

however, is that all the kids know his name. “I could go anywhere<br />

[in this neighborhood] and all the kids will know my name. Everyone<br />

respects us when they see us – ‘Oh, there go The Fishermen!’”<br />

This good will extends from local parents and their children<br />

to the mostly white police who patrol the Meer. They have a<br />

noticeable rapport with The Fishermen, characterized by inside<br />

jokes and gear donations. Nat is confident that the park uplifts<br />

the community. “We walk down the block and the parents say,<br />

‘Thank you for keeping my son away from the building.’”<br />

Spending time with the fishing community at the Meer makes<br />

it easy to understand these feelings. Instead of being stuck in their<br />

apartments or on their blocks with nothing to do, men like Mel,<br />

Nat and Country have the Meer to thank for their evolution from<br />

under- or unemployed locals, to public figures and respected mentors.<br />

The organization is unregistered, unfunded and informal, yet<br />

The Fishermen form an institution that provides valuable services<br />

to nearby families and, even more so, to the men of the organization<br />

themselves, who derive a very real sense of self worth from<br />

what they do for their neighbors and for local kids. The Meer<br />

gives The Fishermen a safe, green sanctuary away from the stresses<br />

of both work and home that allows them to form long-lasting<br />

and meaningful social networks with other regulars. Because of<br />

these networks, the Meer becomes a place that offers Nat and<br />

Mel more than just largemouth bass and a good time. Mel knows<br />

when he needs it, the other Fishermen can come through with<br />

opportunities for jobs and housing, as well as emotional support<br />

in tough times.<br />

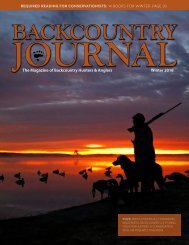

As the day comes to a close the lamps above the bench light up.<br />

The convivial atmosphere The Fishermen enjoy runs on into the<br />

night as they chat and joke. Occasionally, one of them even catches<br />

a fish. Mel jumps up to help a young girl who is wandering a<br />

bit too close to the water’s edge while Nat shows me grainy cell<br />

phone photos of the monster crappie his son caught in the Meer<br />

last year. “It’s a big feeling,” Nat tells me, reflecting on his years of<br />

fishing with local children. “When you see their eyes open up like<br />

50-cent pieces when they catch their first fish, that’s what really<br />

gets ’em. They’re hooked for life.”<br />

Taimur grew up in New York City fishing the Harlem Meer. He<br />

researched this piece on The Fishermen as part of his senior thesis<br />

in sociology at Princeton University. The biggest breakthrough in his<br />

research came from catching a big catfish that everyone at the Meer<br />

wanted to hear about.<br />

46 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL SUMMER 2017<br />

SUMMER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 47