Issue 95 / Dec18/Jan19

Dec 2018/Jan 2019 double issue of Bido Lito! magazine. Featuring: CHELCEE GRIMES, REMY JUDE ENSEMBLE, AN ODE TO L8, BRAD STANK, KIARA MOHAMED, MOLLY BURCH, THE CORAL, PORTICO QUARTET, JACK WHITE and much more.

Dec 2018/Jan 2019 double issue of Bido Lito! magazine. Featuring: CHELCEE GRIMES, REMY JUDE ENSEMBLE, AN ODE TO L8, BRAD STANK, KIARA MOHAMED, MOLLY BURCH, THE CORAL, PORTICO QUARTET, JACK WHITE and much more.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Varaidzo illustrates some of the people and stories from Liverpool’s<br />

historic black community that she feels should not just be celebrated<br />

during Black History Month, but always.<br />

Varaidzo is a best-selling writer, editor, podcaster and artist from London. Her essay was featured in the award-winning anthology<br />

The Good Immigrant in 2016, and her words have appeared in the New Statesman, Complex, Dazed and Gal-Dem, for which<br />

she previously served as Arts and Culture Editor. Last year, her mum’s move to Liverpool sparked Varaidzo’s curiosity in our city’s<br />

history. Upon learning that Liverpool was likely home to the oldest black community in Europe, she became interested in researching<br />

the city’s historical black figures. As part of her Instagram project over the duration of this year’s Black History Month – where she illustrated<br />

and profiled the lives and attainments of pre-Windrush black people from across the UK – she profiled five black people who either lived or<br />

were born in Liverpool.<br />

Black History Month has now ended, but our attempts as a city to educate ourselves about our past should be never stop. Liverpool’s<br />

involvement in the slave trade is embedded into the architecture around us, built on the back of the prosperity of those times – the opulence of<br />

St. George’s Hall and Liverpool Town Hall obscures an unacknowledged human cost. Even today, many of our street names honouring slave<br />

traders and anti-abolitionists remain unchanged, with Penny Lane and Rodney Street being just two of the most prominent. This history of<br />

racism has meant that the lives and successes of Liverpool’s black people have often been overlooked and undervalued.<br />

By drawing these figures out of obscurity in the format of the times, Varaidzo offers Bido Lito! readers an education of our city’s past that<br />

should be part of an essential history curriculum. She is now extending her research into the black people of Liverpool’s past and present for<br />

her podcast series Search History, with an episode dedicated to Liverpool scheduled for the early months of next year.<br />

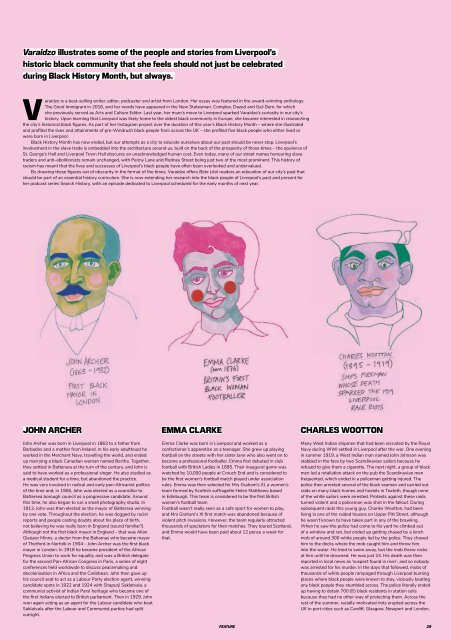

JOHN ARCHER<br />

John Archer was born in Liverpool in 1863 to a father from<br />

Barbados and a mother from Ireland. In his early adulthood he<br />

worked in the Merchant Navy, travelling the world, and ended<br />

up marrying a black Canadian woman named Bertha. Together,<br />

they settled in Battersea at the turn of the century, and John is<br />

said to have worked as a professional singer. He also studied as<br />

a medical student for a time, but abandoned the practice.<br />

He was very involved in radical and early pan-Africanist politics<br />

of the time and, in 1906, John was elected as a councillor to<br />

Battersea borough council as a progressive candidate. Around<br />

this time, he also began to run a small photography studio. In<br />

1913, John was then elected as the mayor of Battersea winning<br />

by one vote. Throughout the election, he was dogged by racist<br />

reports and people casting doubts about his place of birth,<br />

not believing he was really born in England (sound familiar?).<br />

Although not the first black mayor in England – that was Allan<br />

Glaisyer Minns, a doctor from the Bahamas who became mayor<br />

of Thetford in Norfolk in 1904 – John Archer was the first black<br />

mayor in London. In 1918 he became president of the African<br />

Progress Union to work for equality and was a British delegate<br />

for the second Pan-African Congress in Paris, a series of eight<br />

conferences held worldwide to discuss peacemaking and<br />

decolonisation in Africa and the Caribbean. John then gave up<br />

his council seat to act as a Labour Party election agent, winning<br />

candidate spots in 1922 and 1924 with Shapurji Saklatvala, a<br />

communist activist of Indian Parsi heritage who became one of<br />

the first Indians elected to British parliament. Then in 1929, John<br />

won again acting as an agent for the Labour candidate who beat<br />

Saklatvala after the Labour and Communist parties had split<br />

outright.<br />

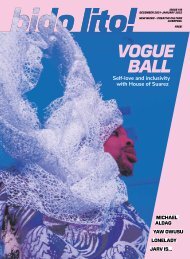

EMMA CLARKE<br />

Emma Clarke was born in Liverpool and worked as a<br />

confectioner’s apprentice as a teenager. She grew up playing<br />

football on the streets with her sister Jane who also went on to<br />

become a professional footballer. Emma first debuted in club<br />

football with British Ladies in 18<strong>95</strong>. Their inaugural game was<br />

watched by 10,000 people at Crouch End and is considered to<br />

be the first women’s football match played under association<br />

rules. Emma was then selected for Mrs Graham’s XI, a women’s<br />

team formed by Scottish suffragette Helen Matthews based<br />

in Edinburgh. This team is considered to be the first British<br />

women’s football team<br />

Football wasn’t really seen as a safe sport for women to play,<br />

and Mrs Graham’s XI first match was abandoned because of<br />

violent pitch invasions. However, the team regularly attracted<br />

thousands of spectators for their matches. They toured Scotland,<br />

and Emma would have been paid about 12 pence a week for<br />

that.<br />

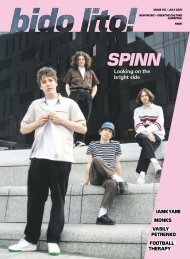

CHARLES WOOTTON<br />

Many West Indian shipmen that had been recruited by the Royal<br />

Navy during WWI settled in Liverpool after the war. One evening<br />

in summer 1919, a West Indian man named John Johnson was<br />

stabbed in the face by two Scandinavian sailors because he<br />

refused to give them a cigarette. The next night, a group of black<br />

men led a retaliation attack on the pub the Scandinavian men<br />

frequented, which ended in a policeman getting injured. The<br />

police then arrested several of the black seamen and carried out<br />

raids on many black homes and hostels in Toxteth, though none<br />

of the white sailors were arrested. Protests against these raids<br />

turned violent and a policeman was shot in the fallout. During<br />

subsequent raids this young guy, Charles Wootton, had been<br />

living in one of the raided houses on Upper Pitt Street, although<br />

he wasn’t known to have taken part in any of the brawling.<br />

When he saw the police had come to his yard he climbed out<br />

of a window and ran, but ended up getting chased by a lynch<br />

mob of around 300 white people led by the police. They chased<br />

him to the docks where the mob caught him and threw him<br />

into the water. He tried to swim away, but the mob threw rocks<br />

at him until he drowned. He was just 24. His death was then<br />

reported in local news as ‘suspect found in river’, and so nobody<br />

was arrested for his murder. In the days that followed, mobs of<br />

thousands of white people rampaged through Liverpool burning<br />

places where black people were known to stay, viciously beating<br />

any black people they stumbled across. The police literally ended<br />

up having to detain 700 (!!!) black residents in station cells<br />

because they had no other way of protecting them. Across the<br />

rest of the summer, racially-motivated riots erupted across the<br />

UK in port cities such as Cardiff, Glasgow, Newport and London.<br />

FEATURE<br />

29