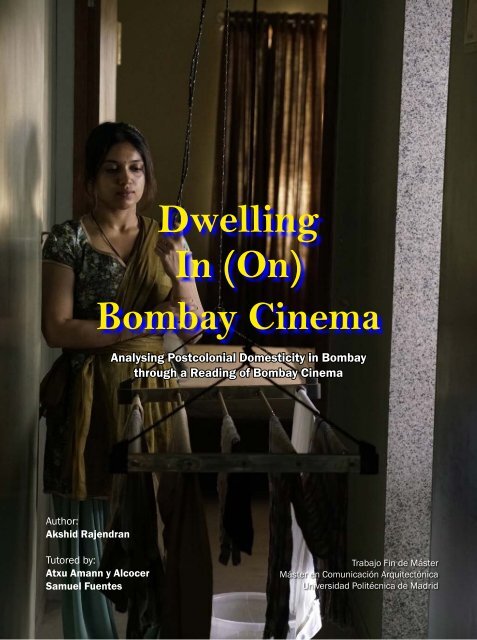

Dwelling In (On) Bombay Cinema

Dwelling In (On) Bombay Cinema is an experimental research into the domestic condition of Bombay through a reading of Bombay cinema. It composes of an audio-visual product and the following textual documentation of the investigation methodology. These two entities are intended to be archived together digitally and physically. This work is part of the final assignment (trabajo fin de máster) of the masters programme in architectural communication or MAca (Máster Universitario en Comunicación Arquitectónica ) in the Superior Technical School of Architecture of Madrid (Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid) under the Technical University of Madrid (Universidad Politécnica de Madrid). The following document is to accompanied by the digital essay-film available through the following link: https://youtu.be/OO8dxD5Ypos The investigation is authored by Akshid Rajendran. And tutored by Atxu Amann y Alcocer and Samuel Fuentes. January 2019.

Dwelling In (On) Bombay Cinema is an experimental research into the domestic condition of Bombay through a reading of Bombay cinema. It composes of an audio-visual product and the following textual documentation of the investigation methodology. These two entities are intended to be archived together digitally and physically. This work is part of the final assignment (trabajo fin de máster) of the masters programme in architectural communication or MAca (Máster Universitario en Comunicación Arquitectónica ) in the Superior Technical School of Architecture of Madrid (Escuela Técnica Superior de

Arquitectura de Madrid) under the Technical University of Madrid (Universidad Politécnica de Madrid).

The following document is to accompanied by the digital essay-film

available through the following link: https://youtu.be/OO8dxD5Ypos

The investigation is authored by Akshid Rajendran.

And tutored by Atxu Amann y Alcocer and Samuel Fuentes.

January 2019.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Dwelling</strong><br />

<strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>)<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

Analysing Postcolonial Domesticity in <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

through a Reading of <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

Author:<br />

Akshid Rajendran<br />

Tutored by:<br />

Atxu Amann y Alcocer<br />

Samuel Fuentes<br />

Trabajo Fin de Máster<br />

Máster en Comunicación Arquitectónica<br />

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid

ii

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

https://youtu.be/wMxVQrqA1XY

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong> is an experimental research into the<br />

domestic condition of <strong>Bombay</strong> through a reading of <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema.<br />

It composes of an audio-visual product and the following textual documentation<br />

of the investigation methodology. These two entities are<br />

intended to be archived together digitally and physically.<br />

This work is part of the final assignment (trabajo fin de máster) of the<br />

masters programme in architectural communication or MAca (Máster<br />

Universitario en Comunicación Arquitectónica ) in the Superior Technical<br />

School of Architecture of Madrid (Escuela Técnica Superior de<br />

Arquitectura de Madrid) under the Technical University of Madrid<br />

(Universidad Politécnica de Madrid).<br />

The following document is to accompanied by the digital essay-film<br />

available through the following link:<br />

https://youtu.be/wMxVQrqA1XY<br />

The investigation is authored by Akshid Rajendran.<br />

And tutored by Atxu Amann y Alcocer and Samuel Fuentes.<br />

January 2019.<br />

iv

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

To an inaccessible domesticity from the past,<br />

obsessed with Bollywood.<br />

v

vi

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong>(<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

Acknowledgements<br />

As an architect, I began this investigation with the intention of gaining<br />

insight into an already well-studied and documented topic while<br />

swaying away from the traditional, academic and disciplined methodologies<br />

customarily proposed in architecture schools. For initially believing<br />

in these ideas and offering to tutor me, I am grateful to Atxu.<br />

Atxu played a vital role in this research by constantly trying to push<br />

me out of my rational and logical boundaries yet remain in control<br />

of a dazzling intuition within me that at times was difficult to grasp.<br />

Sam, unfortunately can’t be thanked enough. While initially agreeing<br />

to help me with only the audiovisual aspects of my research, he<br />

became a much more intrinsic part of the project involving himself<br />

with everything from skimming through books with me at the library<br />

to sending me shiba memes at 3am to pacify my pre-deadline stress.<br />

This research would be lacking in essence without Sam’s constant<br />

presence.<br />

Perhaps she would say it is merely her job, but Antonella, throughout<br />

the investigation, has been an incredible guiding force helping me to<br />

find direction during every moment of the investigation from precisely<br />

hypothesising to preparing the final presentation down to the last<br />

word.<br />

Lastly, I owe this work to the MACA-3 family without whom, the last<br />

year-and-a-half would be unrecognisable.<br />

vii

Contents<br />

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

Preface to the Study 1<br />

Hypothesis and Objectives 3<br />

Project Scope 4<br />

Theoretical Framework 5<br />

To Dwell in <strong>Bombay</strong> is to Survive 5<br />

Domesticity in <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong> 15<br />

Confronting the Archives 19<br />

The Image on the Screen 19<br />

Postcolonial <strong>Bombay</strong> 20<br />

Identifying Parameters 22<br />

Communication Strategy and Methodology 27<br />

The Formats 29<br />

The Narrative 30<br />

Part B: The Film-Essay<br />

Constructing the Narrative 33<br />

Finding a Home in the City 33<br />

The City is not Wholeheartedly Urban 35<br />

Scattered Domesticity 38<br />

Maids, Housewives and Queens of the Havelis 40<br />

Storytelling in the Scenic Haveli 43<br />

Another Surrealist Escape from Urban Claustrophobia 46<br />

Social Reform in <strong>Bombay</strong> and <strong>Cinema</strong> 49<br />

The Deeply Political Lives of the Urban Poor 53<br />

The Antagonist and Personifying Power 56<br />

Structuring the Essay 59<br />

Achieving Narrative Fluidity 59<br />

viii

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

Guided and “Free” Storytelling 60<br />

The Verbal Essay 63<br />

Prelude to the Text 63<br />

The Text 63<br />

Music and Soundtrack 68<br />

Minimalism and Hindustani Classical Music 68<br />

Vande Mataram 69<br />

M.I.A. and the Slum as a Labyrinth 70<br />

City Slums Slums 71<br />

Pacing with the Storyboard 74<br />

Editing 74<br />

Cuts and Transitions 74<br />

Transitioning Sound 75<br />

Part C: Conclusions<br />

Reflections 81<br />

Studying the Narrative 83<br />

Revisiting the Video Essay 83<br />

Looking for Balance 84<br />

Roleplaying 85<br />

Final Meditations 85<br />

Appendices<br />

Bibliography 91<br />

<strong>On</strong>line References 96<br />

Audiovisual References 98<br />

Films Referenced 98<br />

<strong>On</strong>line Audiovisual References 106<br />

Documentaries and T.V. Series 107<br />

ix

List of Figures<br />

Figure 1.1: An aerial view that depicts the asymmetry of housing in <strong>Bombay</strong>.<br />

Source: businessinsider. (2018, October 2). Drone photos of Mumbai reveal the<br />

places where extreme poverty meets extreme wealth. Retrieved January 14, 2019,<br />

from https://www.businessinsider.es/aerial-drone-photos-mumbai-extreme-wealthslums-2018-9<br />

Figure 1.2: An archetypical street in the slums of <strong>Bombay</strong>. Source: https://www.<br />

flickr.com/photos/urbzoo/29001316384/<br />

Figure1.3: A still from ‘Vertical City’ (Kishore, 2010) depicting the dystopia of slum<br />

rehabilitation architecture and obsolete buildings. https://www.d-word.com/images/film_images/04.jpg?1304577183<br />

Figure 1.4: A still from the viral song, “Mere Gully Mein” performed by DIVINE<br />

and Naezy, rappers from the “streets” of Dharavi and proponents of <strong>Bombay</strong>’s hiphop<br />

culture. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bK5dzwhu-I<br />

Figure 1.5: A chart showing the chronological organisation of <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

from the 1950s to the 2000s (Wright, 2017, p. 22)<br />

Figure 1.6: Diagram depicting the seven parameters idetified, classified into environmental,<br />

social and economic parameters and their corresponding observations enlisted.<br />

Figure 2.1: A still from Lust Stories depicting, from a low-angle shot, the silence that<br />

populates a middle-class house during a typical working day.<br />

Figure 2.2: A scene from Salaam <strong>Bombay</strong>! depicting the amalgamated nature of the<br />

footpath<br />

Figure 2.3: A scene from Salaam <strong>Bombay</strong>! showing a young girl who is asked to<br />

wait outside her house as her mother, an escort, is teasing a client<br />

Figure 2.4: Khabi Khushi Khabie Gham... used spatial vastness to reinforce ideas of<br />

social and familial hierarchy. Source: Khabi Khushi Khabie Gham...<br />

Figure 2.5: Rohan Raichand (Hrithik Roshan) struts down a street in London with<br />

a dozen women assisting him in forgetting the urban chaos in <strong>Bombay</strong>, but remembering<br />

the colours of the <strong>In</strong>dian flag. Source: Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham...<br />

Figure 2.6: Vicky’s father storms towards him as he dances, cross-dressed, his family<br />

watching him amused and unsuspecting. Source: <strong>Bombay</strong> Talkies.<br />

8<br />

9<br />

11<br />

13<br />

21<br />

25<br />

34<br />

29<br />

39<br />

44<br />

47<br />

51<br />

x

Figure 2.7: Krishna from Salaam <strong>Bombay</strong>! buys a ticket to <strong>Bombay</strong> before he becomes 54<br />

Chaipau, the teaboy. Source: Salaam <strong>Bombay</strong>!<br />

Figure 2.8: A scene featuring Anil Kapoor being watched in a theatre in Dharavi 56<br />

reclaiming the life of his mother and his destroyed criminal lifestyle from Babia, a<br />

random underworld don. Source: Dharavi<br />

Figure 2.9: The newly created chapters interconnect with the initial parameters in a 49<br />

seamless fashion<br />

Figure 2.10: Structuring the linear narrative 67<br />

Figure 2.11: The crossfade transition used to move to London 76<br />

Figure 2.12: The water-splashing-transition used to exit the title screen 76<br />

Figure 2.13: Silence and a dusty afternoon before Paper Planes by M.I.A. 76<br />

Figure 2.15: Final storyboard 78

xii<br />

This page is intentionally left blank

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

This page is intentionally left blank<br />

xiii

Part A:<br />

An Extended<br />

Prologue

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

Preface to the Study<br />

With the intention of addressing the condition of the “dwelling”<br />

in the city of Mumbai 1 (<strong>In</strong>dia), through an analytical criticism of<br />

the cinema shot and produced in the city, <strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

<strong>Cinema</strong> elaborates an experiment in architectural communication<br />

involving a practical undertaking, succeeded by a theoretical reflection.<br />

The film industry of <strong>Bombay</strong>, not including its success as a diverse<br />

and interdisciplinary medium of mass entertainment, has<br />

been an object of academic scrutiny for decades (Chakravarty,<br />

1989; Prasad, 2000; Mishra, 2002; Wright, 2017). The film industry<br />

produces close to 400 films every year, accounting to about<br />

43% of the net turnout of <strong>In</strong>dian cinema (“Bollywood revenues<br />

may cross Rs 19,300 cr by FY17,” 2016). It is this vast number<br />

of films that constitutes the alternate realm of the “cinematic<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong>” 2 and it is precisely this “<strong>Bombay</strong>” that will be explored<br />

throughout this investigation.<br />

The following study deals with the symbolic relationship between<br />

cinema and city. While much has been written about this “power-couple”<br />

(Leigh & Kenny, 1996; Clarke, 1997; Sawhney, 2012;<br />

Edelman, 2016), the precise nature of their relationship is constantly<br />

in flux. <strong>Cinema</strong> is known to influence cities and their visual<br />

identities, economies and built environments (Shiel, 2011,<br />

p.2). The city, on the other hand, simultaneously gives place to<br />

the movie, helps in storytelling, and in some cases, as does Rome<br />

in The Great Beauty (Sorrentino, 2013), Hiroshima in Hiroshima,<br />

My Love (Resnais, 1959) and the fictitious Gotham city in the film<br />

adaptations of the Batman DC comic book series, the city is found<br />

to seemingly become a vital part of the original cast.<br />

1. <strong>Bombay</strong> was renamed<br />

to Mumbai in an attempt<br />

to ethnicise urban space<br />

in 1993 by the Hindu<br />

political right as part<br />

of the Hindu-Muslim<br />

riots that gripped<br />

the city in December<br />

1992. <strong>In</strong> this study, the<br />

“<strong>Bombay</strong>” referred to<br />

is the cinematic urban<br />

space that has defined<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong> cinema since its<br />

inception.<br />

2. Bollywood is part<br />

of a larger <strong>In</strong>dian film<br />

industry. Hindi cinema<br />

is often metonymously<br />

referred to as Bollywood.<br />

<strong>In</strong> this study, <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

cinema refers to the<br />

body of Hindi cinema<br />

produced in <strong>Bombay</strong>.<br />

1

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

3. The term “dwell”<br />

has been defined by<br />

Heidegger in ‘Building<br />

<strong>Dwelling</strong> Thinking’<br />

(2009, p. 145) and<br />

referred to in the<br />

‘Theoretical Framework’<br />

chapter of this<br />

document.<br />

The object of concern in this study is not the entire city, rather it<br />

focusses on the domestic scale. The house, although emphatically<br />

varying in typology both in cinema, is often the primary seat<br />

of the character’s urban adventures. The characters are found to<br />

scale the urban arena in an attempt to combat the sociocultural<br />

dynamics found both within the city and the film, only to return<br />

home repeatedly as a necessary means of recovery. Curiously, to<br />

actually find a house in the city is a demanding process that films<br />

generally assume for granted. It is well known that housing in<br />

developing cities like <strong>Bombay</strong> is a multifarious social issue. <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

experiences wide disparities in housing conditions between<br />

the affluent and the lower-middle income groups living in the city.<br />

Despite a vibrant economic growth in the city since independence<br />

(“GDP growth (annual %) | Data,” 2019), housing conditions have<br />

not improved proportionately in postcolonial <strong>Bombay</strong> (Appadurai,<br />

2000, p. 629). With comfortable living conditions accessible<br />

at a premium and the working class often residing in cramped<br />

and poor-quality spaces, the poor inevitably take to the footpaths.<br />

Notwithstanding this crippling housing crisis, <strong>Bombay</strong> continues<br />

to attract migrants in search of new opportunities (“2018 Revision<br />

of World Urbanization Prospects,” 2018), causing further<br />

demands in housing, thereby contributing to a cycle that becomes<br />

increasingly difficult to disrupt.<br />

To dwell 3 “in” <strong>Bombay</strong> is to confront this reality of urban claustrophobia.<br />

It is to innocently step into the city, attempting to search<br />

for order from within the chaotic, oily machine that is <strong>Bombay</strong>.<br />

To dwell “on” <strong>Bombay</strong> is to reflect on its cinema. It is to confront<br />

an alternate reality and therefore to dive into the depths of one<br />

the largest resources available to use for social introspection in<br />

the city.<br />

2

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

The study is carried out in a manner that facilitates its own communication.<br />

There are two components to the envisioned final<br />

product:<br />

a. A film-essay combining content from a selection of <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

films is to help create a narrative wherein the viewer<br />

is to glimpse the “dwelling” in <strong>Bombay</strong> solely through its<br />

story told by <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema.<br />

b. A verbal or textual account of the investigation process.<br />

Owing to cinema’s complexity and the absence of an instruction<br />

manual, in order to attain its full functioning capacity as a legitimate<br />

resource, the tools used to interpret cinema need to be constantly<br />

reinvented. Although the final audio-visual product can<br />

exist on its own, it must, whenever possible, be accompanied by a<br />

pictorial, graphic or the following textual account of the process<br />

of investigation as a necessary means to facilitate the use of cinema<br />

as an archival resource in urban study.<br />

Hypothesis and Objectives<br />

Although the issue of housing in <strong>Bombay</strong> is complex and distressing,<br />

there is a certain clarity that arises from consolidating the relationship<br />

between city and cinema. The city is clearly not perfect.<br />

<strong>In</strong> its entirety, the city is a damaged organism because its constituent<br />

units are damaged. The city is thus required to regularly heal<br />

itself through various methods of introspection. Out of precisely<br />

this triangular link between cinema, city and introspection, one<br />

can thereby hypothesize the following:<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong> cinema can function as an effective, valuable<br />

and interdisciplinary resource in order to better<br />

visualize the city’s urban domestic condition<br />

and its various facets.<br />

3

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

4. The components and<br />

academic framework of<br />

this work is outlined on<br />

page ii.<br />

Synthesizing the need to communicate the analytical study in order<br />

to create knowledge that contributes to the body of academic<br />

investigations into housing in <strong>Bombay</strong> and additionally, if <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

cinema were to indeed be a legitimate means of social introspection,<br />

the primary objective becomes evident:<br />

To communicate the domestic condition of the<br />

“dwelling” in <strong>Bombay</strong> through a reading of its cinema<br />

using an audio-visual discourse to an urban<br />

and academic audience.<br />

Project Scope<br />

The following study is developed within the Master in Architectural<br />

Communication programme at the Technical University in<br />

Madrid.<br />

The project 4 proposed is an experimental exercise in architectural<br />

communication wherein the product (the audio-visual) is designed<br />

to convey the findings of an analytical study to a partly<br />

pre-defined public. The study doesn’t merely involve communicating<br />

existing observations. Rather, the observations themselves<br />

are organised with an awareness of their capability of being communicated.<br />

Although the archives are required to be filtered and<br />

navigated in a logical way, there is no unique method that can be<br />

followed in order to filter the films that are to be analysed. The<br />

filtering and selection methodology is outlined in the chapter1.3<br />

entitled: “Confronting the Archives.”<br />

The project shall consist of two phases: the first including the research<br />

within the realm of <strong>Bombay</strong>’s cinematic universe including<br />

popular cinema shot and recording in <strong>Bombay</strong>. Consequently, the<br />

second phase involves production of the communicative product<br />

using digital film editing proceeded by an analytical critique of<br />

the same product in order to arrive at the relevant conclusions.<br />

4

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

The communicative product, in this case from a constructionist<br />

perspective, should include both the product and the developmental<br />

process within the product itself. Thereby the entirety of the<br />

product is not restricted to the audio-visual film. It is the audio-visual<br />

film, the physical object that stores a digital version of the<br />

audio-visual film, a textual account of the investigation process,<br />

and wherever necessary, a verbal presentation of the investigation<br />

process that all constitute the entirety of the product.<br />

Theoretical Framework<br />

To Dwell in <strong>Bombay</strong> is to Survive<br />

Those few people who have had the privilege to find a home in<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong> would recognise merely by stepping out of their houses<br />

that to find intimacy and shelter in the city is not undemanding.<br />

Paradoxically, a city like <strong>Bombay</strong>, with its unconstrained urban velocity,<br />

is precisely one that requires more than any other, that the<br />

city’s housing market be highly operational. Observing the city’s<br />

traits, immediately what we find is an eccentric disjunction; one<br />

that has often been attributed to the coalescing between the dynamisms<br />

of corrupt politics, real-estate investors or arbitragers, and<br />

organised crime networks (Appadurai, 2000, p. 648). To address<br />

this asymmetry in the availability of the basic human necessity<br />

of a dwelling is to demand that the city self-medicate, that it consciously<br />

take on a process of self-inquiry and introspection, one<br />

that the city is evidently already engaged with. However, delving<br />

deeper into this process, we find that there are innumerable<br />

tools that can be used to help us with our task of introspection.<br />

<strong>On</strong> one hand we have oceans of academic scientific literature on<br />

the domestic condition of <strong>Bombay</strong> (Sen, 1976; Appadurai, 2000;<br />

Dwivedi, 2001; Padora, 2016). <strong>On</strong> the other hand, we have an im-<br />

5

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

mense, alternate archive of documentation of an altered reality<br />

of <strong>Bombay</strong> in the form of literary and cinematic fiction. These<br />

alternate imaginaries have repeatedly given us insight into a <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

that we previously struggled to find access to (Upstone, 2007;<br />

Mazumdar, 2007; Raj & Sreekumar, 2017). Consequently, finding<br />

ourselves strung between two universes we can enable ourselves<br />

to bring a more meditated and considerate discernment into the<br />

complex matter of what it means to dwell in <strong>Bombay</strong>.<br />

When Heidegger, in the setting of the poetics of domesticity,<br />

morphologically analysed the German word “bauen” (2009, p. 145),<br />

what this meant for readers was a consolidation of two concepts,<br />

i.e., to “dwell” and to “exist.” The act of inhabiting the earth became<br />

the very meaning of human existence and thereby, the verb<br />

“to inhabit” began to assume a similar connotation as the verb “to<br />

be.” To dwell however is not simply to occupy space. To confront<br />

the complexities of manifesting one’s own shelter in flawless harmony<br />

with one’s environment is to begin to dwell.<br />

This very hypothesis of shelter is one that postulates the moral<br />

superiority of order over chaos. The house tends to, in addition<br />

to providing technological shelter from nature’s climatic turmoil,<br />

create order against nature’s spatiotemporal sense. Houses permit<br />

orderly human activity not only spatially within the city but also<br />

temporally within human lives. It has been pointed out that the<br />

phrase “to go back home” uses the word “back” in a non-instinctive<br />

fashion to express future arrival (Dovey, 1985, p. 37). What Dovey<br />

emphasised as the house’s sinusoidal nature along a constant<br />

time continuum was further explored in the same issue of Home<br />

Environments centring on several dimensions of domestic temporality<br />

(Werner, Altman, & Oxley, 1985). While the house clearly<br />

occupies infinite places on a linear timeline, perhaps in the context<br />

of domesticity, time is not meant to be seen as linear. The periodic<br />

temperament of time is perhaps tremendously more significant to<br />

6

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

human life and its cyclicity. Salman Rushdie, in his magical realist<br />

masterpiece, Midnight’s Children (1981) which was set partly in<br />

postcolonial <strong>Bombay</strong> and furthermore through later essays (Rushdie,<br />

1991, p. 12), has emphasized how our homes can become a<br />

temporal place from the past. Affectionately, he identifies his readers<br />

as immigrants of this distant country that presently manages<br />

to share a common humanity. The identity of the “home” thereby<br />

becomes amorphous over time, rendering perhaps its momentary<br />

functions more stable objects of observation insofar as they be<br />

viewed outside of their larger context of human life.<br />

Phenomenologist Gaston Bachelard has argued that the primary<br />

function of home is to allow the human being to observe or to<br />

“daydream”, going on further to verbalise his objective (Bachelard,<br />

Jolas, & Stilgoe, 1994, p. 6) as:<br />

I must show that the house is one of the greatest powers<br />

of integration for the thoughts, memories and dreams of<br />

mankind. The binding principle in this integration is the<br />

daydream. Past, present and future give the house different<br />

dynamisms, which often interfere, at times opposing, at<br />

others, stimulating one another.<br />

5. Tononi’s theory is<br />

mathematical framework<br />

to understand the<br />

subject-object duality<br />

of experience. For<br />

Bachelard, experience<br />

didn’t have this<br />

character. Consiousness<br />

in the external domestic<br />

space didn’t “feel” like<br />

something in the inside,<br />

nor did it appear to be<br />

perceivable from another<br />

standpoint. Rather, it just<br />

directly “felt”. The space<br />

appeared directly “on the<br />

inside.” His first-person<br />

observations were coming<br />

from the object istelf.<br />

The role that the house is to assume in Bachelard’s study, and<br />

his principle of integration is reminiscent of the experientialist,<br />

mathematical theory of information integration of consciousness<br />

5 (Tononi, 2008). Tononi does not speak of domesticity. He<br />

does however assist us in verbalising what philosophers like Descartes<br />

were confused about in their meditations, i.e., that there is<br />

an “internal” subjective experience that can be observed while observing<br />

the “outside” world. For Bachelard, it was the same role<br />

that daydreaming would play. So important for him was this role,<br />

that the entire function of the house was to provide the peacefulness<br />

necessary to conduct this daydreaming. What appears to be<br />

7

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

6. <strong>Bombay</strong>’s socioeconomic<br />

hierarchies<br />

are not the traditional<br />

<strong>In</strong>dian ones. Traditional<br />

rural Hindu <strong>In</strong>dia is<br />

known for its temple<br />

towns wherein social<br />

identities are based on<br />

religious roles and family<br />

history. <strong>Bombay</strong> however,<br />

is a globalised capitalist<br />

metropolitan city.<br />

an experientialist view of domestic space reveals itself to be compatible<br />

with a utilitarian one wherein the domestic space is seen as<br />

a space for shelter. <strong>In</strong> effect, not only was the utilitarian view compatible,<br />

it was rudimentary for Bachelard. The spatiotemporal order<br />

that the house intends to impose arises from a predictable set<br />

of human necessities. Cleanliness, nurture, nutrition, self-identity<br />

and belongingness all have a footing in domestic space.<br />

After independence, in a <strong>Bombay</strong> subject to a multitude of socio-political<br />

tensions after independence, what it meant it have<br />

some place in the city to “go back to” and to sleep at was in constant<br />

flux. Urbanisation simply meant urgently moving into the<br />

most affordable home in the city, irrespective of its discomfort,<br />

and building one’s way up a familiar social hierarchy, found today<br />

in most globalised metropolitan cities. For some, this openness<br />

and scalability of the social hierarchy was a new liberation<br />

in contrast to rural religious ideologies that assigned hierarchical<br />

positions by the mere luck of birth 6 (Dumont & Sainsbury, 2010,<br />

p.83). For others it was just a matter of confronting the city’s cha-<br />

8<br />

Figure 1.1: An aerial view that<br />

depicts the asymmetry of housing<br />

in <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

Source: businessinsider. (2018,<br />

October 2). Drone photos of<br />

Mumbai reveal the places where<br />

extreme poverty meets extreme<br />

wealth. Retrieved January<br />

14, 2019, from https://www.<br />

businessinsider.es/aerial-dronephotos-mumbai-extremewealth-slums-2018-9

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

Figure 1.2: An archetypical<br />

street in the<br />

slums of <strong>Bombay</strong>.<br />

Source: https://www.<br />

flickr.com/photos/urbzoo/29001316384/<br />

otic answers to the question of basic human necessities. However,<br />

the experientialist fragment of Bachelard’s notion of daydreaming<br />

was out of question. Even as the city was populated with millions<br />

of comfortable houses and apartments, the spaces between<br />

these homes came to shelter not an insignificant proportion of the<br />

population, but half of the city’s population (Lewis, 2015). They<br />

lived either in shanty, ad-hoc, handmade (not the romantic kind)<br />

shelters or directly on the streets. Today footpaths accommodate<br />

a large percent of <strong>Bombay</strong>’s residential as well as commercial activity.<br />

9

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

According to the World’s Cities data booklet published by the<br />

UN, <strong>Bombay</strong> houses 21.4 million people at a density of around<br />

21,000 /sq.km (2016). However about 60% of this figure consists<br />

of regular citizens living in informal housing, slums and other<br />

unhygienic living conditions. This 60% population is concentrated<br />

on parcels of land that cover a mere 6-8% of the city’s land. Dharavi,<br />

a slum located in the heart of <strong>Bombay</strong>, is Asia’s largest slum<br />

and informally houses between 300,000 to 1 million people, the<br />

exact number being unknown (“Dharavi,” 2019). Many of these<br />

dwellers simply occupy footpaths and construct chawls (informal<br />

houses), sometimes incrementally over decades.<br />

Although, the majority of research on housing in <strong>Bombay</strong> has focussed<br />

on the current poignant state of affordability, there is a<br />

real lacking in architectural study on the homeless. <strong>In</strong> <strong>Bombay</strong>,<br />

the homeless have been handled in literature and film through a<br />

depiction of inner conflict (Nandy, 2007, p. 25).<br />

However Nandy’s exposing of the celebration of homelessness in<br />

the <strong>Bombay</strong>’s imaginaries does not substitute the need for ethnographic<br />

study of the homeless in <strong>Bombay</strong>. A recent study (Dutta,<br />

Lhungdim, & Prashad, 2016) pointed out that more than four out<br />

of five homeless persons, defined as those who reside not within a<br />

census house, are migrants. For a city whose urban space is occupied<br />

by migrants who have been unsuccessful in finding a home,<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong> doesn’t seem to slow down its rate of urbanisation or<br />

increase availability within its housing market.<br />

Migration however is merely a correlation, not the cause of the<br />

housing crisis in <strong>Bombay</strong>. Attempts to point fingers in complex<br />

issues such as housing shortage are easily thwarted by opposing<br />

stakeholders (Shlay & Rossi, 1992, p. 132). Nevertheless, homelessness<br />

seems to only be approached socio-politically while it is<br />

really a story of familial conflict, social oppression, inaccessibility<br />

10

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

Figure1.3: A still from ‘Vertical City’ (Kishore, 2010) depicting the dystopia of slum rehabilitation<br />

architecture and obsolete buildings.<br />

https://www.d-word.com/images/film_images/04.jpg?1304577183<br />

to hygiene or basic infrastructure, and a largely overlooked exclusion<br />

from their communities. Psychologically, the homeless are often<br />

described as lacking identity (Nair & Raghavan, 2014) but the<br />

“pavement” and “slum” dwellers are empowering labels that have<br />

fuelled social movements within localities like Dharavi.<br />

It is not usually the homeless’ lives that are of academic interest.<br />

Various documentaries and video essays have been produced exposing<br />

the lives within the slums of <strong>Bombay</strong>; some professionally<br />

made while others have been published on YouTube by curious<br />

tourists. Dharavi, Slum for Sale (Konermann, 2010) introduces<br />

Dharavi to strangers, from its origins to its rise as an economic<br />

powerhouse in <strong>Bombay</strong>. The documentary exposes the perceived<br />

futility of the lives of the people of Dharavi and their threat of<br />

eviction favouring the Maharashtrian government’s decision to<br />

11

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

use Dharavi land for economic benefit in public-private partnership<br />

projects under the image of slum rehabilitation. A similar<br />

story is told in Vertical City (Kishore, 2010), a film-essay that outlines<br />

the dystopic vertical rehabilitative architecture proposed for<br />

slum dwellers. The documentary successfully communicates the<br />

spatial oppression and repetitive failure of the government in<br />

dealing with the issue of rehabilitating slums. <strong>In</strong> many ways, the<br />

documentary demolishes any hope that government-run projects<br />

that relocate the poorly housed can benefit anyone with the exception<br />

of private investors. The replaced houses are often far from<br />

useful infrastructure like water, building maintenance usually not<br />

included as part of the contract, and houses are usually provided<br />

miles from their original workplaces, thereby disrupting an otherwise<br />

regular economy. Days of malfunctioning elevators eventually<br />

become years of malfunctioning elevators, resulting finally<br />

in paralysed dystopic buildings that have come to symbolise the<br />

displaced, economically-paralysed urban poor.<br />

Many a time, foreign intervention has helped reveal unique and<br />

otherwise concealed aspects of slum life. Notwithstanding the<br />

work done by Danny Boyle in his Oscar-nominated Slumdog Millionaire<br />

(2008), the most popular of such work is the two-part<br />

Kevin McCloud series called Slumming It (Simpson, 2010). Slumming<br />

It is one of the first such audio-visual investigation to have<br />

been labelled “poverty porn” (Thompson, 2010). Perhaps under<br />

the same label, one can categorize the new wave of YouTube videos<br />

that have surfaced such as the video by the channel “bald and<br />

bankrupt” called “Exploring An <strong>In</strong>dian Slum // Dharavi Mumbai”:<br />

the video features an adventurous western male walking<br />

around the <strong>Bombay</strong> streets attempting to comprehend the chaotic<br />

organisation of Dharavi. Similar videos have been made as part of<br />

foreign research interests or personal documentary interests like<br />

“We Spent A Day <strong>In</strong> The Largest Slum <strong>In</strong> <strong>In</strong>dia | ASIAN BOSS”<br />

12

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

Figure 1.4: A still from the viral song, “Mere Gully Mein” performed by DIVINE and Naezy, rappers<br />

from the “streets” of Dharavi and proponents of <strong>Bombay</strong>’s hip-hop culture<br />

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bK5dzwhu-I<br />

by “Asian Boss”, “Documentary - The Way Of Dharavi 2014” by<br />

“Sse Productions bvba” and “My Daily Life in the SLUMS OF<br />

MUMBAI (Life-Changing 5 Days)” by “Jacob Laukaitis”.<br />

Films dealing with the community-empowering hip-hop and “gully<br />

rap” culture of Dharavi that has gripped the city in the previous<br />

decade have also emerged in the last few years such as, “Dharavi<br />

Hustle: Official Documentary” by “Bajaao”, and the slightly more<br />

comprehensive “Vice Asia” documentary, “Kya Bolta Bantai? - The<br />

Rise of Mumbai Rap”. The Zoya Akhtar film Gully Boy (2019) (unreleased<br />

at the time of writing) tackles the same social aspect of<br />

life in Dharavi. What one finds is that there is plenty of informal<br />

sociological study on the issue of Dharavi and plenty of formal<br />

study on the typological and architectural matter but seldom are<br />

the governing bodies writing policy out of a synthesis of the two.<br />

13

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

7. For more information,<br />

watch the YouTube video<br />

entitled, “Why Mumbai<br />

Has Slums” by “Scroll.<br />

in”(https://youtu.be/<br />

jPZp_ICmfhE). We are<br />

explained how politics<br />

and slum rehabilitation<br />

have interplayed to<br />

perpetuate the housing<br />

crisis of <strong>Bombay</strong>.<br />

According to the Economic Survey of <strong>In</strong>dia 2017-18, <strong>Bombay</strong>’s<br />

housing market tolerated about 0.48 million vacant houses 7 (“Economic<br />

survey says not many people are taking up houses in Mumbai”,<br />

2018). “The phenomenon of high vacancy rates is not fully<br />

understood, but unclear property rights, weak contract enforcement<br />

and low rental yields may be important factors. The spatial<br />

distribution of the new real estate may also be an issue, as the vacancy<br />

rates generally increase with distance away from the denser<br />

urban core,” the Survey pointed out.<br />

Clearly the issue of housing in <strong>Bombay</strong>, as with any other globalised<br />

city of such scale in developing countries, is one that requires<br />

a rigorously multi-disciplinary approach to solution. The issue is<br />

not merely one to do with influencing the governing bodies in the<br />

right manners. Rather it is to do with recognising urban vulnerabilities<br />

(Parthasarathy, 2009, p. 116) and thereby studying the<br />

spatial consequences of the capitalist pyramid that defines cities<br />

like <strong>Bombay</strong>. Although many have pointed toward global trends<br />

that have influenced <strong>Bombay</strong>’s asymmetric growth, the true culprits<br />

are the open market policies that changed <strong>In</strong>dian in the late<br />

80s and early 90s (Nijman, 2000, p.582). Liberalism in the new<br />

urbanised <strong>In</strong>dian city fermented a hierarchy that the poor were<br />

perhaps used to but only beginning to accept. <strong>On</strong> the other hand,<br />

the working upper-middle-class in search of a complacent city life<br />

largely ignored these struggles while the academics and intellectuals<br />

wrote books and made films about them. Perhaps most accurately<br />

described in the scientific study on the “Matthew Effect”<br />

and allocation of resources (Merton, 1968, p.62), as the rich get<br />

bigger houses, the poor have to fight to keep the shanty structures<br />

they currently own. Ethnographic studies of <strong>Bombay</strong>’s poor and<br />

homeless have helped us understand to a limited extent the nature<br />

of the city’s chaotic street life but have not given us insight<br />

comparable to that received from the fictions produced in <strong>Bombay</strong>.<br />

14

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

This is partly because the architects and sociologists studying the<br />

housing crisis in <strong>Bombay</strong> are not storytellers. The storytellers,<br />

on the other hand, do know how to graciously combine interdisciplinary<br />

study with compelling narratives and produce popular<br />

media that eventually is understood by the masses. Consequently,<br />

investigation into <strong>Bombay</strong>’s domestic condition would remain incomplete<br />

without turning to its massive produce of films. Ranjani<br />

Mazumdar has aptly called <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema an “archive of the<br />

city” (2007), emphasising how cinema in <strong>Bombay</strong> is a momentous<br />

cultural force that not only documented the city as it flourished<br />

but also participated in the “feedback loop” that allowed cultural<br />

transformation to occur. Looking into this archive, we begin to<br />

comprehend the true complexity of domesticity in <strong>Bombay</strong>.<br />

Domesticity in <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

Since the first silent film was released in <strong>Bombay</strong> in 1913, the city’s<br />

cinema industry mastered the art of sensorial communication and<br />

accumulated a wealth of subjective insights into <strong>Bombay</strong>’s urban<br />

life film by film. The movie-making business in <strong>In</strong>dia is the world’s<br />

largest 8 by measure of its quantity of output 9 (Punathambekar,<br />

2013, p.51). By the 1930s, <strong>In</strong>dian cinema was already producing<br />

more than 200 films a year. Today that figure is close to 2000 including<br />

all <strong>In</strong>dian languages. <strong>Bombay</strong> and its cinema have grown<br />

significantly over the last century; however, it would be difficult to<br />

assert which influenced the other to a greater degree.<br />

8. Bollywood has often<br />

been called the world’s<br />

largest film industry.<br />

However, Bollywood is<br />

restricted to the Hindi<br />

film industry. What<br />

is being referred is<br />

generally a combined<br />

“<strong>In</strong>dian film industry”<br />

that comprised in 2017<br />

of 1986 films in 27<br />

different languages.<br />

(Film Feredation of<br />

<strong>In</strong>dia, 2017)<br />

9. The measure here is<br />

the output of the film<br />

industry. <strong>In</strong> terms of<br />

ticket sales, the <strong>In</strong>dian<br />

film industry outsells<br />

Hollywood by about<br />

900,000 tickets (“<strong>Cinema</strong><br />

of <strong>In</strong>dia,” 2019).<br />

However Hollywood is a<br />

higher-grossing industry.<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong> cinema has not attained its scholastic position in modern<br />

sociological and filmographic study by simply following a preconceived<br />

blueprint of an appropriate social trajectory. To say that<br />

the industry does not have its own purpose, would likely make it<br />

difficult to identify common patterns of intentionality over any<br />

single period of time, but it is not to say that there have not been<br />

any trends in film genre evolution. <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema commenced<br />

15

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

with projection the silent films broadcasting culturally familiar<br />

religious narratives (Jamal, 1991) but as a postcolonial <strong>In</strong>dia<br />

struggled to find its place globally, and urbanisation began slowly<br />

altering century-long rural conventions, numerous films like<br />

Mother <strong>In</strong>dia (Khan, 1957) began to change the social perception<br />

of suppressed sections of society and even empowering urban<br />

women. These nationalist themes began to find themselves in a<br />

progressively socio-politically-tense <strong>In</strong>dia and consequently, the<br />

working-class’ long-muffled anger was personified in the “angry<br />

man” genre, as in Deewaar (Chopra, 1975) and Zanjeer (Mehra,<br />

1973). Subsequent to the communal tensions of the early 90s,<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong> would continue to secularly publicise the damage<br />

caused by the fundamentalist communal terror inflicted upon the<br />

city in <strong>Bombay</strong> (Ratnam, 1995), Black Friday (Kashyap, 2007), and<br />

the The Attacks of 26/11 (Varma, 2013). While film has obviously<br />

influenced popular culture, fashion and the music industry alike,<br />

the film industry has served as an archive “deeply saturated with<br />

urban dreams” of the city’s history (Mazumdar, 2007, p. xxxv).<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong> has been shown by numerous scholars to be the<br />

greatest reservoir of the urban experience of <strong>Bombay</strong> at our disposal,<br />

and with good reason. From high-budget to low-budget,<br />

every film representing the city of <strong>Bombay</strong> has recreated or rethought<br />

urban space to craft a unique cinematic archive of the city.<br />

Not only has <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema successfully acted as a sort of escape<br />

from the troubles of a city-life, it has acted as a self-reflexion<br />

of the collective urban vision of <strong>Bombay</strong>. <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema has remained<br />

through the turn of the millennium as the clearest, most<br />

immediate and entertaining medium of communication with the<br />

masses.<br />

Owing to its characteristic captivating nature, <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema as<br />

a medium of communication for social change has been explored<br />

by various filmmakers. <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema since its inception has<br />

16

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

stuck close to social issues and interpreted them through visual<br />

art, drama, song and dance.<br />

<strong>In</strong> the introduction to The Secret Politics of our Desires (Nandy,<br />

1999), the author cleverly recognizes the metaphorical relation between<br />

<strong>In</strong>dian cinema and the slum, claiming that the political climate<br />

in <strong>In</strong>dia is influenced by the sheer power of numbers of the<br />

slum and their closeness to the realities of urban life. The slum<br />

and the cinema thereby become not only a mirror of each other,<br />

but effective tools of study for introspection. As has been demonstrated<br />

(Young, 1969), in the late 60s and early 70s, fictional film<br />

was often devoid of any sort of complicated socio-cultural statement.<br />

Such a conclusion comes from a quick analysis of films such<br />

as Weekend (1967) by Godard or Shame (Bergman, 1968). Young<br />

goes on to criticise filmmakers such as Godard stating that although<br />

later films tackled social issues, they have done so in a quasi-journalistic<br />

style using characters that overshadowed the real<br />

issues themselves. <strong>In</strong> an ethnographic study (2007), Shakuntala<br />

Rao recognises the relation of the slum to its larger social and urban<br />

context. She argues like Nandy that <strong>In</strong>dian cinema represents<br />

the tastes and longings of the slums which dominate the urban<br />

public sphere. However, she goes on to assert, using various interviews<br />

to back up her ethnography, that social messages often get<br />

lost in the commercialisation of <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema.<br />

Today, cinema deals with a far more composite society. While a<br />

voluminous quantity of films tackle a broad assortment of social<br />

issues, others feed into an assortment of social desires for specific<br />

genres including everything from breakneck-speed action sequences<br />

to pseudo-pornographic item numbers, often effortlessly<br />

combining the two in the same genre. <strong>In</strong> this sense, the cinema<br />

industry was the first open marketplace, in its true sense for the<br />

proliferation of ideas, that <strong>In</strong>dia ever managed to create. Although<br />

the entire cinematic archive can be easily regarded as a single or-<br />

17

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

ganisation or entity, it is more precisely a collective reflection of<br />

the city’s subjectivities (Mazumdar, 2007, p. 1). At times, <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

cinema performed the role of a drug, providing an escape from<br />

the unruly troubles of a chaotic city life, while at others, it acted<br />

successfully as a tool for mass introspection. <strong>In</strong> the following<br />

study, <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema shall be scrutinised thoroughly with the intention<br />

of gaining insight into the city’s peculiar urban domestic<br />

condition. To create a framework within which we can analyse the<br />

two-dimensional moving images of this cinematic archive, and in<br />

addition, as the archive is composed of around 400 annual films on<br />

average since the inception of the artform, the process of selection<br />

of our cases for study is of primary importance.<br />

18

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

Confronting the Archives<br />

The Image on the Screen<br />

It has been shown that to be lost in space has only to do with our<br />

humane objectives (Tuan, 2011, p.36). If we find ourselves within<br />

an unfamiliar density of a thick forest with tall canopies and darkness<br />

in every direction, the notions of front and back are rendered<br />

meaningless. However, the moment a flickering light appears in<br />

the distance, we find that we are immediately oriented to a common<br />

spatial objectivity.<br />

The human being, by his mere presence, imposes a schema<br />

on space. Most of the time he is not aware of it. He notes<br />

its absence when he is lost.<br />

<strong>In</strong> cinema, distances and angles remind us of our worldly three-dimensional<br />

spaces on a constrained two-dimensional area. However,<br />

what we define as “spaces” is a metonymic expression for a<br />

complex set of experiential characteristics. <strong>In</strong> the natural environment,<br />

we see objects located in “space”. This spatiality comes<br />

from a unification of the location of the eye and the location of<br />

the object. However, the location of the subject need not be equivalent<br />

to the location of the eye. <strong>In</strong> fact, the subject has no defined<br />

location. The “becoming aware” of the object is separate from the<br />

function and position of the eye.<br />

As the camera mimics the eye in cinema, the location of the camera<br />

needn’t signify the location of the subject. The subject-object<br />

distinction is easily broken in cinema and what is experienced is<br />

not a duality but rather a single final image on screen that communicates<br />

space not as an object or background to be observed<br />

but rather as a characteristic symptom of existence. Hence, our<br />

outlook is inevitably that of a child who is still trying to focus<br />

19

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

on what the outside world is trying to show us; a child who does<br />

not necessarily feel the need to approach reality from a dualist<br />

perspective. Essentially, cinema is not a set of images of the real<br />

world projected on a screen in a dark room. Rather it is a constantly<br />

evolving multi-dimensional reality with its own spatial<br />

and temporal parameters.<br />

Postcolonial <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

<strong>Bombay</strong> cinema shows us its people, its environments and its stories<br />

as we are reading them not as scholars but as citizens of this<br />

cinematic city. Following Tuan’s ideas, the vastness of <strong>Bombay</strong>’s<br />

cinematic space need be no cause for disorientation. Our focus remains<br />

on the cinematic representation of the domestic space of<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong> in all possible senses within the realm of audio-visual<br />

communication. This means that we shall only restrict our focus<br />

to cinematic production that occurs within <strong>Bombay</strong> and the general<br />

group of films that use the “<strong>Bombay</strong> house” as a part of the<br />

cinematographic set and/or as a character within the movie. The<br />

following step is to place chronological constraints.<br />

The very task of classifying <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema has been attempted<br />

in the past through varying methodologies resulting in a large<br />

spectrum of insightful sub-genres. Perhaps the most ambiguous<br />

yet documented genre is the masala genre that surged in popularity<br />

from the 60s onwards (Wright, 2017, p. 23). Wright provides us<br />

with a flowchart that begins at the inception of <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema in<br />

the first decade of the 20 th century to the current postmodern era<br />

of <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema warning however that “the decades that tend<br />

to be skimmed over in <strong>In</strong>dian cinema timelines are the ones that<br />

have produced less politically oriented and more populist films.”<br />

Although, our initial filter is the temporal characteristic of postcolonial<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong>, a purely chronological view of <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema<br />

20

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

1910s–20s Mythologicals (Films like Raja Harichandra,<br />

based on Hindu texts: Ramayana, Mahabharata)<br />

1930s–40s Stunt movies (Star persona: Fearless<br />

Nadia)<br />

1950s Socials: the ‘Golden Era’ (Directors: Raj Kapoor,<br />

Guru Dutt, Bimal Roy)<br />

Figure 1.5: A chart<br />

showing the chronological<br />

organisation<br />

of <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

from the 1950s to the<br />

2000s (Wright, 2017,<br />

p. 22)<br />

[1960s: overlap with 1950s]<br />

1970s ‘Angry Man’ era and Parallel <strong>Cinema</strong> movement<br />

peak (Social retribution action films; directors<br />

Shyam Benegal and Ritwik Ghatak)<br />

[1980s: overlap with 1970s. Dip in cinema-going due<br />

to rise of television] (Doordarshan channel launches<br />

successful Ramayana TV series)<br />

1990s NRI and Family Movies (Diaspora-oriented<br />

productions; patriotic, traditionalist, family-oriented<br />

‘multi-starrers’)<br />

[2000s: continuation of 1990s?]<br />

does not help classify films, rather it helps perhaps simply gather<br />

an understanding of various trends. The postcolonial city begins<br />

with the “Golden Age” of <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema. This has been shown<br />

in Vitali’s Not a Biography of “<strong>In</strong>dian <strong>Cinema</strong>” to be an era where<br />

cinematic trends were began to be influenced by western and external<br />

sources, thereby rendering film study problematic (as cited<br />

in Wright, 2017, p. 26).<br />

Taking on a more humanist perspective, Mazumdar divided her<br />

book, <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong>: An Archive of the City (2007) into five<br />

chapters namely, ‘Rage on Screen’, ‘The Rebellious Tapori’, ‘Desiring<br />

Women’, ‘The Panoramic <strong>In</strong>terior’ and ‘Gangland <strong>Bombay</strong>’.<br />

21

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

Brilliantly, she walks us through a non-chronological winding<br />

path through the multiple thematical subjects that she finds the<br />

cinema of <strong>Bombay</strong> to archive only to reveal how these five subjects<br />

have been of utmost social importance to <strong>Bombay</strong> as a megapolis.<br />

<strong>Bombay</strong> is an enormous city, but perhaps not as large as the<br />

fictional reality created by its film industry. <strong>Bombay</strong>’s cinematic<br />

archive is one that spans thousands of films in a multitude of<br />

genres and multi-genres.<br />

The following list can be compiled taking into account merely the<br />

temporal “postcolonial” period, and the use of the city-scape as a<br />

space for production and/or setting. Further parameters can be<br />

examined in order to create a balance between, independent and<br />

popular films, foreign and national productions, female and male<br />

producers and directors, etc.<br />

Identifying Parameters<br />

Our question of domesticity involves a wide range of cinematic<br />

objects. From women to footpaths to large doors. The intention<br />

mustn’t be to merely meditate on architectural and domestic<br />

elements visible on the screen. Rather it is to use cinema as the<br />

inter-disciplinary, narrative medium it was designed to be. The<br />

idea is to observe the full spectrum of cinematic objects and their<br />

context with the intent to identify the elements that help tell the<br />

story of housing in <strong>Bombay</strong>. Looking for apt objects for studying<br />

the “dwelling”, <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema is seen to talk generously about<br />

the following facets.<br />

The #interiors of the house are spatially insulated from the dense<br />

claustrophobic city. This is vital not only architecturally for the<br />

city to function, but also in cinema as the characters tackle the<br />

complexities of the various realms of cinematic spatial reality.<br />

Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (Barjatya, 1994) shows us how through<br />

22

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

clever production, the modern consumerist, globalised aesthetic<br />

can coexist with tradition and nostalgia. This is the same juxtaposition<br />

that was further explored and seemed to work well commercially<br />

in the millennial family films like Kabhi Khushi Kabhie<br />

Gham… (Johar, 2001), Baghban (Chopra, 2003) or Kabhi Alvida<br />

Naa Kehna (Johar, 2006). Non-Resident <strong>In</strong>dians (NRI) audiences<br />

received these high-budget productions with open arms and<br />

revelled in the nostalgia they deeply identified with (Mazumdar,<br />

2007). <strong>Cinema</strong> finds ways to tackle this either through surreal<br />

filming locations or through extravagant panoramic sets. The<br />

family film movie genre could not have succeeded without the<br />

architecture of vastness of the #Haveli(mansion). They allowed<br />

space for <strong>Bombay</strong> to disappear and for the new modern <strong>In</strong>dian to<br />

dream the ideal lifestyle.<br />

Often the spatial separation exists around the abode, but urban<br />

chaos manages to bleed into the home. This is especially true for<br />

the slums of <strong>Bombay</strong>. The #lower_middle-class dwells in this<br />

blended city space uninsulated from the chaotic synergies of <strong>Bombay</strong>.<br />

The house is often shared by large joint families. And the private<br />

space, although successfully separated from the public, ironically<br />

becomes almost as dense as it. <strong>In</strong> Dharavi (Mishra, 1992),<br />

the #protagonist is seen vigorously battling the puppet strings<br />

attached to him within the socio-economic hierarchy. His plans to<br />

open his own factory while supporting his family by being a <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

taxi-driver are expectedly thwarted as the plot develops. But<br />

we see that as his mother visits his house in the city, how a shanty<br />

one-room house with a temporary roof quickly becomes crowded<br />

with conflicting interests and narratives.<br />

The #people of the house are often the central focus of domestic<br />

narratives. Female roles although domestic tend to be experimental<br />

within the domestic realm. <strong>Cinema</strong>tic experimentation<br />

was seen from the very beginning of <strong>In</strong>dian cinema, to defy so-<br />

23

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

ciety’s preconceptions of femininity. Fearlessness and women’s<br />

anger were often the expected domestic character in cinema. The<br />

females played often authoritative mothers who sought to climb<br />

the power hierarchy of the family tree. As individualism rose, and<br />

women stopped playing queens of the Haveli, owning a housemaid<br />

instead became the new middle-class aspiration.<br />

The house is often deeply tied to the #livelihoods of the lower<br />

middle class. It is used by cinema to describe a specific socio-economic<br />

story. The #homeless protagonist negotiates the political<br />

landscape and often uses their living-on-the-#footpath as a metaphor<br />

that justifies the use of violence as therapy. For their suffering<br />

needs no justification. It is the city that is harsh. And the<br />

domestic condition of the slums verily fuels anger against the established<br />

systems of power in the inevitably corrupt city. When<br />

cinema shows us instead the settled-abroad, complacent lives of<br />

the “middle-class” what we find is a socio-economic ambiguity that<br />

opposes the rural tendency to rely on livelihoods for storytelling.<br />

The <strong>Bombay</strong> home is #private insofar that it separates public spaces<br />

of the city from the familial, protected space of a home. However,<br />

the city’s density means that intimacy is not always achieved<br />

easily. <strong>In</strong> fact, while the city is populated with an extremely large<br />

number of houses, the amount of intimate spaces is scarce. They<br />

are scattered into various pockets of the city where intimacy is<br />

either rented or borrowed. Sexual expression is a constant slave<br />

of this domestic situation.<br />

<strong>In</strong> Life in a... Metro (Basu, 2007), the character Rahul, played by<br />

Sharman Joshi, owns a lavish apartment space in downtown <strong>Bombay</strong>.<br />

We get a glimpse of Rahul’s job as one that exerts diligence<br />

and discipline and his home inevitably, a luxuriant 2- or 3-bedroom<br />

apartment with wide corridors and floor-to-ceiling windows.<br />

Rahul, being a single successful man, lives alone. His house<br />

24

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

Figure 1.6: Diagram depicting the seven parameters idetified, classified into environmental,<br />

social and economic parameters and their corresponding observations enlisted.<br />

functions as a #flexible_space that accommodates him and friends<br />

of his that are trying to find a place to have sex in the city. Because<br />

even hotels in <strong>Bombay</strong> moral polices. Various characters in the<br />

movie borrow the keys to Rahul’s apartment and use his bedroom<br />

as an intimate space, including by his boss who cheats on his wife<br />

and sleeps with a friend of Rahul’s. The home thus makes itself<br />

25

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

intimate only temporarily in concentrated pockets of the city’s<br />

housing spectrum.<br />

The idea of the #scattered_domus transforms the city into a single<br />

domestic space where toilets, dining and intimacy are all outsourced<br />

to the available infrastructure. The home eventually becomes<br />

the city itself.<br />

<strong>In</strong> Lust Stories (Kashyap, Akhtar, Banerjee & Johar, 2018), the segment<br />

directed by Karan Johar shows us how the typical <strong>Bombay</strong><br />

home houses a joint family. And the newly-married couple doesn’t<br />

necessarily obtain the intimacy that they would expect when<br />

starting a new life together. Rather, the bride typically shares<br />

space with the groom’s extended family. This becomes even more<br />

challenging when the houses are smaller in the denser areas of<br />

the city.<br />

When the dwelling is an integral part of the film, the #political<br />

discourse also tends to be. The new #slum_architecture was<br />

inextricably tied to politics in the city. Films don’t tell us what<br />

the newspapers do. But Kaala (Ranjith, 2018), a film featuring<br />

the Tamil superstar Rajinikanth, talks extensively about how the<br />

slum dwellers of <strong>Bombay</strong> constantly struggle with a navigation<br />

problem within the political field; one that their day-to-day existence<br />

is based on. The film goes on to ostentatiously criticise the<br />

top-down approach to affordable housing in the city.<br />

Looking broadly at the parameters identified, <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema<br />

presents itself as an assortment of thematically varied audio-visual<br />

resources. The parameters can be grouped into spatial and<br />

socio-economic tags. <strong>In</strong> order to organise our archival material,<br />

the following tags can be utilised to better classify the footage.<br />

There might be #economic factors such as the livelihoods of the<br />

characters, often the central synopsis of the film. #environmental<br />

factors like housing typologies and housing interiors that can but<br />

26

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

not necessarily point towards other socioeconomic markers. Lastly,<br />

there are #social themes that generally occupy a large portion<br />

of screen-time and eye-tracked area of the frame. They are usually<br />

the basic cog work of storytelling and generally function as the<br />

mirror through which the viewer enters the cinematic world, and<br />

thereby the vehicle through which she can explore this universe.<br />

Communication Strategy<br />

and Methodology<br />

Film study has in recent years, through the ease of technological<br />

requirements for video-editing and the incentivising of fan-made<br />

content, has grown popular steadily. <strong>Cinema</strong> being an audio-visual<br />

artform, can be communicated effectively through a reincarnated<br />

medium that uses images, audio and language to communicate<br />

the proposed ideas. This reinvented medium, the essay film, video<br />

essay, or essay video must combine a set of selected audio-visual<br />

elements in a particular order to tell a story or to sew the observations<br />

together.<br />

The investigation is to be carried out in an experimental fashion<br />

wherein the film-essay does not serve as a means to communicate<br />

the product of a thorough investigation. Rather the film-essay itself<br />

is part of the investigation process insofar that it integrates<br />

various methods of reflecting on the state of cinema as a means<br />

both of social interpretation and mass communication. The film<br />

essay does not guarantee a unique method of conveying a rigid<br />

investigation. <strong>In</strong>stead, it is the outcome of a particular selection<br />

of precise criteria. Owing to the wide subjectivity built within the<br />

cinematic format, the study would be perhaps radically different<br />

yet equally valid if it were to be carried out with a different set of<br />

parameters.<br />

27

Part A: An Extended Prologue<br />

The targeted audience can be tagged loosely into two groups. <strong>On</strong><br />

one hand, the resident of <strong>Bombay</strong> and its cinematic world; one<br />

who has visited the city physically or through any of its films, one<br />

who has formed a mental image of the city. <strong>On</strong> the other hand, we<br />

have the curious scholar to whom the city-cinema relationship is<br />

of academic interest.<br />

As the observations are reorganised, a linear, parallel multi-linear,<br />

non-linear or circular narrative can be found in order to link up<br />

the observations. Using the same audio-visual tools used in cinema<br />

may not always bring a positive outcome, however since film is<br />

the primary medium being recycled, the potential tools need to be<br />

given enough attention.<br />

Whether the narrative is visual, aural or verbal, we have hypothesized<br />

that <strong>Bombay</strong> cinema can be studied as a resource to understand<br />

housing in the city and hence the study is inevitably always<br />

a subjective view of the city through cinema, an already subjective<br />

view of the city.<br />

These urban subjectivities cannot be presented as axioms. They<br />

are indeed perspectives from multiple points of view, tied together<br />

by a single point of view. Subjective observations out of a subjective<br />

medium are always haphazard. Hence it is this single point of<br />

view that can guide an audience through the cacophonic assortment<br />

of films that talk about the homes of <strong>Bombay</strong>.<br />

The following process inevitably requires the researcher to take<br />

up various roles. The researcher needs to be aware of an extremely<br />

large cinematic archive and use specialised knowledge to make<br />

a primary selection. Simultaneously, the same person is required<br />

to assume the role of the producer and organise the necessary<br />

resources, permissions, music and other skills necessary to complete<br />

the task. As the pieces come together, the director is required<br />

verify the script and prepare the tonality of the voice-over while<br />

28

<strong>Dwelling</strong> <strong>In</strong> (<strong>On</strong>) <strong>Bombay</strong> <strong>Cinema</strong><br />

guiding the editor to correctly organise the collected data all while<br />

constantly verifying the same with the researcher.<br />

The Formats<br />

The essay video is a medium that incorporates theoretical framework,<br />

citations and references, and employs an audio-visual rhetoric<br />

to communicate ideas (van den Berg, 2013). <strong>On</strong>e of the primary<br />

objectives being to generate an effective means to communicate<br />

the study, carefully deciding the medium of communication becomes<br />

vital. Uploading the finished product onto an online video<br />

streaming service like “vimeo” can allow it to blend seamlessly<br />

into a pre-existing academic realm of audio-visual and film study.<br />

This would require for the video to be as consumable as possible.<br />

A length between 12 - 15 minutes should prove enough to communicate<br />

the observations. Longer than this would equate to appealing<br />

to a more academic audience and shorter would not suffice<br />

to cover the relevant observations.<br />

<strong>In</strong> order to step out of the finished essay video product and attempt<br />

to also communicate the process, the format for process-communication<br />

becomes equally important. Accommodating for flexibility<br />

of format here can become essential to obtain the largest reach.<br />

The communication of the process can also happen in an audio-visual<br />

format, but in the case that there is a live screening to a public,<br />

the presentation can be made personal depending on the needed<br />

situation. The format can vary from a written account, to schematic<br />

illustrations of processes to a short video summarising the<br />

relevant rhetoric. This can then be attached to the uploaded file,<br />

to the disc, or uploaded along with the finished video onto a social<br />

media platform. However, in order to effectively consolidate both<br />