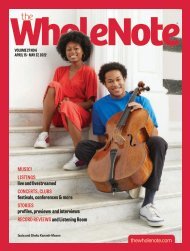

Volume 24 Issue 7 - April 2019

Arraymusic, the Music Gallery and Native Women in the Arts join for a mini-festival celebrating the work of composer, performer and installation artist Raven Chacon; Music and Health looks at the role of Healing Arts Ontario in supporting concerts in care facilities; Kingston-based composer Marjan Mozetich's life and work are celebrated in film; "Forest Bathing" recontextualizes Schumann, Shostakovich and Hindemith; in Judy Loman's hands, the harp can sing; Mahler's Resurrection bursts the bounds of symphonic form; Ed Bickert, guitar master remembered. All this and more in our April issue, now online in flip-through here, and on stands commencing Friday March 29.

Arraymusic, the Music Gallery and Native Women in the Arts join for a mini-festival celebrating the work of composer, performer and installation artist Raven Chacon; Music and Health looks at the role of Healing Arts Ontario in supporting concerts in care facilities; Kingston-based composer Marjan Mozetich's life and work are celebrated in film; "Forest Bathing" recontextualizes Schumann, Shostakovich and Hindemith; in Judy Loman's hands, the harp can sing; Mahler's Resurrection bursts the bounds of symphonic form; Ed Bickert, guitar master remembered. All this and more in our April issue, now online in flip-through here, and on stands commencing Friday March 29.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Something in the Air<br />

Saluting Musical Forebears<br />

without Replication<br />

KEN WAXMAN<br />

French actress Simone Signoret titled her memoirs, Nostalgia Isn’t<br />

What It Used to Be, and the number of uninspiring salutes to<br />

earlier jazz heroes or heroines easily bears out this sentiment.<br />

However, when the right player selects the right material to record<br />

from a celebrated predecessor’s music and – most importantly – puts<br />

his or her own spin on it, the release becomes more than an exercise<br />

in nostalgia. Each of these sessions shows how this feat can be<br />

accomplished.<br />

Ornette Coleman: Reflecting his influence on improvised music<br />

following his sudden arrival on the scene in the late 1950s, it’s no<br />

surprise that two of the sessions honour alto saxophonist Ornette<br />

Coleman (1930-2015). What is remarkable though is that neither<br />

group plays the same Coleman compositions. Plus each takes a<br />

diametrically opposite approach.<br />

Italian drummer Tiziano Tononi & the<br />

Ornettians’ Forms and Sounds: Air<br />

Sculptures (Felmay fy 7058 felmay.it)<br />

features an 11-piece band which, besides<br />

nine compositions by Coleman, interprets<br />

Tononi’s The Air Sculptures Suite. It’s not<br />

just Tononi’s indomitable rhythms from<br />

drum set and other percussion that animate<br />

his CD, but how soloists preserve their identities although immersed<br />

in Coleman’s sounds. Tracks such as the Tononi-composed Fireworks<br />

in N.Y.C and Fort Worth Country Stomp interpret aspects of Coleman’s<br />

music without copying. The latter track, for instance, is a country<br />

blues played with Italian panache featuring sharp staccato slurs and<br />

snorts from alto saxophonist Piero Bittolo Bon, spurred by backbeat<br />

drumming; while Fireworks in N.Y.C is straightforward swing,<br />

tempered by trumpeter Alberto Mandarini’s brassy and graceful solo<br />

plus hearty bass clarinet glissandi from Francesco Chiapperini. It<br />

climaxes with percussion outgrowths that are as African as American,<br />

highlighting Tononi’s cowbell and kalimba. This ingenuity remains<br />

with the Coleman compositions. The expected outlines of Peace<br />

for instance, are reconfigured when propelled by Tito Mangialajo’s<br />

walking bass line and penetrating twangs from Paolo Botti’s banjo (!).<br />

At breakneck tempo, Bittolo Bon’s high-pitched flute and Emanuele<br />

Parrini’s violin stops brighten the performance without losing the<br />

melody. Similarly Rushhour is played acoustically, but with a swelling<br />

sound reminiscent of Coleman’s electric band, and is led by Parrini’s<br />

sizzling double stops as Daniele Cavallanti’s bluesy tenor sax and the<br />

drummer drive everyone forward. Cavallanti brings the same intensity<br />

to Law Years paired with brassy upsurges from Mirko Cisilino’s<br />

trumpet. The lineup on Una Muy Bonita with Mangialajo and Silvia<br />

Bolognesi both playing bass plus Bittolo Bon and Chiapperini on alto<br />

saxophones, allows soloists to reconfigure Coleman with elevated<br />

tremolos or flutter tonguing as the dual basses propel the narrative.<br />

There are only six players on trumpeter Chris Pasin’s Ornettiquette<br />

(Planet Arts 301820 planetarts.org), but two of them, vibist/<br />

pianist Karl Berger and vocalist Ingrid Sertso worked with Coleman.<br />

Beside five Coleman tunes interpreted are two by Pasin and one by<br />

Albert Ayler.<br />

Mostly concentrating on Coleman’s earlier<br />

works, Pasin’s take on Ornettiquette is low<br />

key but inventive. For instance, as Karl<br />

Berger’s vibes elaborate Jayne’s theme, the<br />

band plays up its blues underpinnings at the<br />

same time as Pasin’s clarion blasts are<br />

pitched Maynard Ferguson-like high.<br />

Michael Bisio’s slap bass adds rhythmic<br />

emphasis and the finale is a timbral battle between Pasin and alto<br />

saxophonist Adam Siegel’s supersonic slurs. Ingrid Sertso’s scatting in<br />

tandem with vibraphone clangs and burbling horns almost transforms<br />

When Will the Blues Leave into jittery bebop. But her recitation of the<br />

title and response of “never” reasserts solemnity. Pasin’s OCDC,<br />

saluting Coleman and his trumpeter Don Cherry is more linear than<br />

the dedicatees’ compositions. Plus the trumpeter’s quirky configuration<br />

of Cherry’s role is original. Walking bass and drummer Harvey<br />

Sorgen’s positioned whacks hold the bottom so that the horns can<br />

improvise freely.<br />

Someone who never stinted on the improvisational<br />

or melodic content of his own<br />

compositions was Canadian-born, Londonbased<br />

trumpeter Kenny Wheeler (1930-<br />

2014). Fellow Canadian, trumpeter Ingrid<br />

Jensen and American tenor saxophonist/<br />

clarinetist Steve Treseler lead a seven-piece<br />

band on Invisible Sounds for Kenny<br />

Wheeler (Whirlwind Recordings WR 4729<br />

whirlwindrecordings.com) playing nine Wheeler tunes that are<br />

audible, not invisible. Bookended by a studio and a live version of<br />

Foxy Trot, which in its live incarnation trots along courtesy of Jon<br />

Wikan’s crisp drumming and an array of arpeggios spilling from<br />

Geoffrey Keezer’s piano, the set emphasizes Wheeler’s versatility.<br />

Expressive ballads like Where Do We Go from Here are buoyed by<br />

mellow saxophone swoops and upward puffs from the trumpeter, as<br />

piano chording brings out its swing underpinning. Meanwhile, Old<br />

Time is an out-and-out funk tune with a stop-time narrative, shuffle<br />

beat, slurs and snarls from the tenor saxophonist and acrobatic pitches<br />

from Jensen’s open horn. Still the most characteristic interpretation is<br />

of Wheeler’s best known tune, Everybody’s Song but My Own. A<br />

minor key lament, its essence is reflected in harmonic horn melding,<br />

slippery tremolos from Keezer and Jensen’s supple mid-range<br />

pitch slides.<br />

Another composer who has a Canadian<br />

connection via her late ex-husband is<br />

83-year-old Carla Bley. The 12 tunes played<br />

by Finns, pianist Iro Haarla and bassist Ulf<br />

Krokfors plus American drummer Barry<br />

Altschul on Around Again – The Music of<br />

Carla Bley (TUM CD 054 tumrecords.com)<br />

come mostly from her creative beginnings in<br />

the 1960s, coincidentally a time when the drummer was a member of<br />

Paul Bley’s bands that first played this music. Expressing the compositions’<br />

inflections, performances are almost uniformly unhurried and<br />

dampened with percussion accents, double bass stops and focused on<br />

piano-led themes played respectfully. That way motion and melody<br />

are exposed at the same time. The exposition on Batterie, for instance,<br />

picks up sonic colours from keyboard jumps and is extended with<br />

low-pitched bass-string stops and indirect percussion clatters, and<br />

then slyly redirected to the head. Squirming and swaying, Haarla uses<br />

kinetic glissandi to turn the title track into a fantasia that gives the<br />

bassist enough space for plump pumps. Appropriately and subversively,<br />

both And Now, the Queen and Ida Lupino are spun out in<br />

processional fashion, with the latter balancing Krokfors’ heated string<br />

stabs and Haarla’s cooler key manipulation; and the former cleanly<br />

sweeping up tempo with double bass prods that lead to unstoppable<br />

forward motion, soon intensified with variable and emphasized<br />

voicing from the keyboard. The only track to feature a drum solo that<br />

82 | <strong>April</strong> <strong>2019</strong> thewholenote.com