Volume 24 Issue 7 - April 2019

Arraymusic, the Music Gallery and Native Women in the Arts join for a mini-festival celebrating the work of composer, performer and installation artist Raven Chacon; Music and Health looks at the role of Healing Arts Ontario in supporting concerts in care facilities; Kingston-based composer Marjan Mozetich's life and work are celebrated in film; "Forest Bathing" recontextualizes Schumann, Shostakovich and Hindemith; in Judy Loman's hands, the harp can sing; Mahler's Resurrection bursts the bounds of symphonic form; Ed Bickert, guitar master remembered. All this and more in our April issue, now online in flip-through here, and on stands commencing Friday March 29.

Arraymusic, the Music Gallery and Native Women in the Arts join for a mini-festival celebrating the work of composer, performer and installation artist Raven Chacon; Music and Health looks at the role of Healing Arts Ontario in supporting concerts in care facilities; Kingston-based composer Marjan Mozetich's life and work are celebrated in film; "Forest Bathing" recontextualizes Schumann, Shostakovich and Hindemith; in Judy Loman's hands, the harp can sing; Mahler's Resurrection bursts the bounds of symphonic form; Ed Bickert, guitar master remembered. All this and more in our April issue, now online in flip-through here, and on stands commencing Friday March 29.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

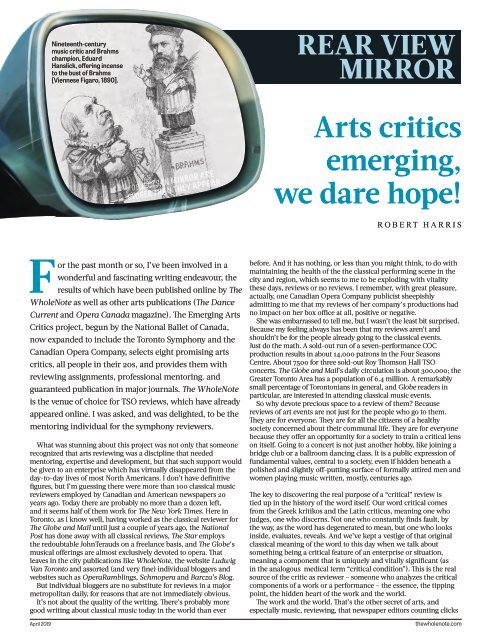

Nineteenth-century<br />

music critic and Brahms<br />

champion, Eduard<br />

Hanslick, offering incense<br />

to the bust of Brahms<br />

[Viennese Figaro, 1890].<br />

REAR VIEW<br />

MIRROR<br />

Arts critics<br />

emerging,<br />

we dare hope!<br />

ROBERT HARRIS<br />

For the past month or so, I’ve been involved in a<br />

wonderful and fascinating writing endeavour, the<br />

results of which have been published online by The<br />

WholeNote as well as other arts publications (The Dance<br />

Current and Opera Canada magazine). The Emerging Arts<br />

Critics project, begun by the National Ballet of Canada,<br />

now expanded to include the Toronto Symphony and the<br />

Canadian Opera Company, selects eight promising arts<br />

critics, all people in their 20s, and provides them with<br />

reviewing assignments, professional mentoring. and<br />

guaranteed publication in major journals. The WholeNote<br />

is the venue of choice for TSO reviews, which have already<br />

appeared online. I was asked, and was delighted, to be the<br />

mentoring individual for the symphony reviewers.<br />

What was stunning about this project was not only that someone<br />

recognized that arts reviewing was a discipline that needed<br />

mentoring, expertise and development, but that such support would<br />

be given to an enterprise which has virtually disappeared from the<br />

day-to-day lives of most North Americans. I don’t have definitive<br />

figures, but I’m guessing there were more than 100 classical music<br />

reviewers employed by Canadian and American newspapers 20<br />

years ago. Today there are probably no more than a dozen left,<br />

and it seems half of them work for The New York Times. Here in<br />

Toronto, as I know well, having worked as the classical reviewer for<br />

The Globe and Mail until just a couple of years ago, the National<br />

Post has done away with all classical reviews, The Star employs<br />

the redoubtable JohnTerauds on a freelance basis, and The Globe’s<br />

musical offerings are almost exclusively devoted to opera. That<br />

leaves in the city publications like WholeNote, the website Ludwig<br />

Van Toronto and assorted (and very fine) individual bloggers and<br />

websites such as OperaRamblings, Schmopera and Barcza’s Blog.<br />

But individual bloggers are no substitute for reviews in a major<br />

metropolitan daily, for reasons that are not immediately obvious.<br />

It’s not about the quality of the writing. There’s probably more<br />

good writing about classical music today in the world than ever<br />

before. And it has nothing, or less than you might think, to do with<br />

maintaining the health of the the classical performing scene in the<br />

city and region, which seems to me to be exploding with vitality<br />

these days, reviews or no reviews. I remember, with great pleasure,<br />

actually, one Canadian Opera Company publicist sheepishly<br />

admitting to me that my reviews of her company’s productions had<br />

no impact on her box office at all, positive or negative.<br />

She was embarrassed to tell me, but I wasn’t the least bit surprised.<br />

Because my feeling always has been that my reviews aren’t and<br />

shouldn’t be for the people already going to the classical events.<br />

Just do the math. A sold-out run of a seven-performance COC<br />

production results in about 14,000 patrons in the Four Seasons<br />

Centre. About 7500 for three sold-out Roy Thomson Hall TSO<br />

concerts. The Globe and Mail’s daily circulation is about 300,000; the<br />

Greater Toronto Area has a population of 6.4 million. A remarkably<br />

small percentage of Torontonians in general, and Globe readers in<br />

particular, are interested in attending classical music events.<br />

So why devote precious space to a review of them? Because<br />

reviews of art events are not just for the people who go to them.<br />

They are for everyone. They are for all the citizens of a healthy<br />

society concerned about their communal life. They are for everyone<br />

because they offer an opportunity for a society to train a critical lens<br />

on itself. Going to a concert is not just another hobby, like joining a<br />

bridge club or a ballroom dancing class. It is a public expression of<br />

fundamental values, central to a society, even if hidden beneath a<br />

polished and slightly off-putting surface of formally attired men and<br />

women playing music written, mostly, centuries ago.<br />

The key to discovering the real purpose of a “critical” review is<br />

tied up in the history of the word itself. Our word critical comes<br />

from the Greek kritikos and the Latin criticus, meaning one who<br />

judges, one who discerns. Not one who constantly finds fault, by<br />

the way, as the word has degenerated to mean, but one who looks<br />

inside, evaluates, reveals. And we’ve kept a vestige of that original<br />

classical meaning of the word to this day when we talk about<br />

something being a critical feature of an enterprise or situation,<br />

meaning a component that is uniquely and vitally significant (as<br />

in the analogous medical term “critical condition”). This is the real<br />

source of the critic as reviewer – someone who analyzes the critical<br />

components of a work or a performance – the essence, the tipping<br />

point, the hidden heart of the work and the world.<br />

The work and the world. That’s the other secret of arts, and<br />

especially music, reviewing, that newspaper editors counting clicks<br />

<strong>April</strong> <strong>2019</strong> thewholenote.com