Voyage 5 Log

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

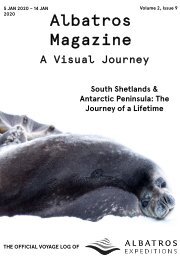

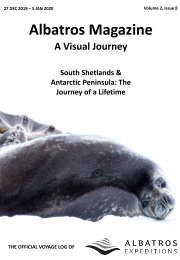

23-30 June, 2019 Volume 1, Issue 5<br />

The Albatros<br />

SVALBARD:<br />

LAST STOP<br />

BEFORE THE<br />

NORTH POLE<br />

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF

The Albatros<br />

Editor-in-Chief:<br />

Staff Writers:<br />

Layout & Design:<br />

Expedition Leader:<br />

Assistant Expedition Leader:<br />

Shop Manager:<br />

Expedition Photographer:<br />

Zodiac Master:<br />

Hiking Master:<br />

Kayak Master:<br />

Rifle Master:<br />

Expedition Guide/Lecturer:<br />

Front Cover Image:<br />

Back Cover Image:<br />

Photography Contributors:<br />

Gaby Pilson<br />

Amanda Dalsgaard<br />

Brian Seenan<br />

Gaby Pilson<br />

Bernabe Urtubey<br />

Steve Egan<br />

Lars Maltha Rasmussen<br />

Nadine Smith<br />

Yuri Choufour<br />

Steve Traynor<br />

Gaby Pilson<br />

Slava Nikitin<br />

Stefano Tricanico<br />

Amanda Dalsgaard<br />

Brian Seenan<br />

Rashidah Lim<br />

Gregers Gjersøe<br />

Wan Meng Chieh<br />

Basha Horyn<br />

Piotr Damski<br />

Thomas Bauer<br />

Diego Punta Fernandez<br />

Bearded Seal © Renato Granieri<br />

Ny-Ålesund © Gaby Pilson<br />

Renato Granieri Photography<br />

Gaby Pilson<br />

Yuri Choufour<br />

© Gaby Pilson<br />

23-30 June, 2019 Volume 1, Issue 5

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

The <strong>Voyage</strong><br />

By the Numbers<br />

Day 1: North to the Future<br />

The Seven Sisters of Szczecin<br />

The King of the Arctic<br />

Day 2: Bears & Belugas in Billefjord<br />

What makes an Expedition Guide?<br />

Day 3: Icy Fjords & Scenic Bays<br />

Ice is Nice – Glacier Fun Facts<br />

Day 4: Into the Ice<br />

Svalbard: A Breeding Ground for<br />

Migrant Birds<br />

Day 5: Krossfjord Adventures<br />

A Love Story<br />

Day 6: The Northernmost Settlement<br />

Polar Diplomacy<br />

Becoming an Expedition Guide<br />

Day 7: The Final Days<br />

A Brief History of the Zodiac<br />

Day 8: Home Again<br />

A Final Note<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

11<br />

12<br />

13<br />

14<br />

15<br />

16<br />

17<br />

18<br />

19<br />

20<br />

21<br />

22<br />

23

The <strong>Voyage</strong><br />

Page 4<br />

The following map traces the approximate route that the M/V Ocean Atlantic took during our<br />

voyage around Svalbard. You can find more information about our day to day activities, landings,<br />

and excursions on the following pages. We hope that this magazine serves as a reminder of all of<br />

the wonderful memories you made while experiencing the Arctic with us at Albatros Expeditions.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

By the Numbers…<br />

Page 5<br />

<strong>Voyage</strong> Statistics:<br />

Northernmost Point:<br />

Total Distance Travelled:<br />

79 o 50.541’N, 10 o 08.286’E<br />

578 nautical miles<br />

Longyearbyen: 78 o 12.651’N, 15 o 32.408’E<br />

Smeerenburg: 79 o 44.821’N, 11 o 05.908’E<br />

NW Svalbard: 79 o 50.541’N, 10 o 08.286’E<br />

Möllerfjorden: 79 º 16.502’N, 11 º 51.052’E<br />

Ny-Ålesund: 78 o 54.871’N, 11 o 59.759’E<br />

Alkhornet: 78 o 13.116’N, 13 o 52.718’E<br />

Excursion Locations:<br />

Billefjord: 78 º 28.702’N, 14 º 15.457’E<br />

Magdalenefjord: 79 o 35.485’N, 11 o 18.981’E<br />

Pack Ice Cruise: 79 o 37.137’N, 10 o 21.263’E<br />

14 Julibukta: 79 o 07.554’N, 11 o 48.352’E<br />

Ny-London: 78 o 56.237’N, 12 o 01.548’E<br />

Ymerbukta: 78 o 16.144’N, 13 o 59.390’E<br />

During our time on the M/V Ocean Atlantic, we consumed:<br />

Beef<br />

Lamb<br />

Pork<br />

Poultry<br />

Cold Cuts<br />

Fish & Seafood<br />

Eggs<br />

Milk<br />

Cheese<br />

Ice Cream<br />

Vegetables<br />

Fruit<br />

Wine<br />

Beer<br />

Toilet Paper<br />

400kg<br />

150kg<br />

350kg<br />

350kg<br />

150kg<br />

500kg<br />

4500pcs<br />

500L<br />

200kg<br />

250L<br />

2000kg<br />

2500kg<br />

450 bottles<br />

650 cans<br />

350 rolls<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

North to the Future<br />

23 June 2019 - Embarkation Day<br />

As our flights touched down on the runway in<br />

Longyearbyen, we were treated to delightful views of<br />

the Arctic landscape that will become our playground<br />

for the next week. Weary from our early morning<br />

flights, yet excited for the adventure to come, we<br />

immediately journeyed into town for some quick city<br />

exploration in Longyearbyen.<br />

The story of Longyearbyen is short, but industrial,<br />

although it didn’t start out that way. As the history<br />

books tell us, the notion of Longyearbyen as a<br />

potential settlement first came about when John<br />

Munro Longyear was on an arctic cruise with his<br />

family in 1903. While sailing around the many fjords<br />

that make Svalbard the picturesque landscape we<br />

know and love, Longyear spotted some potential coal<br />

mining opportunities in Isfjord. By 1906, he began his<br />

mining operations in what was then known as<br />

Longyear City.<br />

Page 6<br />

From the <strong>Voyage</strong> <strong>Log</strong><br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

Once we got our fill of the shopping and walking<br />

opportunities in Longyearbyen, we headed off to<br />

the pier to finally embark on our new home, the<br />

M/V Ocean Atlantic, via a short, but exciting zodiac<br />

ride - our first of many on this expedition. After the<br />

hotel check-in process was complete, we were<br />

treated to a scrumptious afternoon tea, before our<br />

mandatory safety drill in the late afternoon. Soon<br />

enough, we were casting away the bowlines,<br />

heading away from our safe harbour, and<br />

journeying out to sea, in true expedition style.<br />

After our safety drill, we had an opportunity to<br />

wander around the ship and acquaint ourselves<br />

with our new home. Before long, however, we<br />

gathered up in the Viking Lounge yet again for an<br />

introductory briefing with Expedition Leader Berna<br />

Urtubey and his 16 expedition staff members.<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

Although coal mining is no longer as abundant as it<br />

once was in Svalbard, it has forever left its mark on<br />

the region, least of all by creating the small, but<br />

bustling settlement of Longyearbyen. These days,<br />

however, Longyearbyen is a centre for international<br />

science efforts, tourism, and conservation, and, most<br />

importantly for us: the starting point on our journey.<br />

As we’re on an expedition, we know full well that<br />

there are no guarantees. We are at the mercy of the<br />

weather, the wildlife, and the landscape of this cold<br />

and often inhospitable place. But, as explorers know<br />

all too well, we can only ever experience true<br />

beauty in nature when we are brave enough to seek<br />

it out amongst the mountains and the seas in the<br />

world’s most remote places. It is with that<br />

sentiment in mind that we venture away from<br />

Longyearbyen and north, to the future and all the<br />

wonders it holds.<br />

“<br />

We can only ever experience true<br />

beauty in nature when we are<br />

brave enough to seek it out…<br />

”<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

23-30 June, 2019 Volume 1, Issue 5

The Seven Sisters of Szczecin<br />

David MacDonald, Lecturer (Geology) & Expedition Guide<br />

M/V Ocean Atlantic was launched in 1986 as the<br />

last-built of the ‘Shoshtakovich’ class of icestrengthened<br />

passenger vessels, alongside six sister<br />

ships, together known as the “Seven Sisters of<br />

Szczecin.<br />

Her original name was Konstantin Chernenko<br />

(Константин Черненко), after the President of the<br />

USSR (1984-1985). She was renamed Russ (Русс) in<br />

1989, and spent much of her life working in the<br />

Russian Far East.<br />

She was purchased by Albatros Expeditions and<br />

completely refitted in 2017. She is now a 200-<br />

passenger expedition vessel and is one of the<br />

strongest polar cruise ships afloat. Here are some<br />

fun facts about the “Seven Sisters”:<br />

• All seven ships were built by Stocnia Szczecinska<br />

shipyard in Szczecin, Poland between 1979-1986<br />

• Main engines: 4 x Skoda Sulzer 6LZ40 total power<br />

12800 kW, giving a maximum speed of 18 knots<br />

• Most of the class have one bow thruster (736 kW)<br />

and one stern thruster (426 kW); however, two<br />

ships, including ours, built in 1986, have two stern<br />

thrusters, each of 426 kW<br />

• Feature Siemens stabilisers for seaworthiness<br />

• Although built as ferries, they have a<br />

strengthened car deck for transport of tanks<br />

• Two of them had diving chambers<br />

• MV Mikhail Sholokov had hull demagnetising<br />

Page 7<br />

equipment so it could operate in minefields<br />

• All of these ships have been scrapped except ours<br />

and Konstantin Simonov – now Ocean Endeavour<br />

Our ship has had a complex history:<br />

1986-1987 In Baltic traffic, then Vladivostok to<br />

Japan & S Korea<br />

1989 renamed to Russ<br />

1997-1999 In traffic Stockholm-Riga; 2000<br />

Odessa-Haifa; 2002 back to<br />

Vladivostok transporting cars from<br />

Japan<br />

2007 Sold to Sea Ferry Shipping in Majuro<br />

and renamed 2010 to Atlantic;<br />

renovations in Italy and in traffic<br />

Stockholm-Helsinki-St.Petersburg<br />

during summer and laid up (October<br />

2010) in St Petersburg<br />

2012 Sold to ISP in Miami and renamed to<br />

Ocean Atlantic under Marshall<br />

Islands flag<br />

2013 Used as a hotel ship in the German<br />

bight wind farm project<br />

2015-2017 Laid up in Helsingborg and taken to<br />

Gdansk in Poland, where totally<br />

refitted<br />

2017 Chartered to Quark Expeditions<br />

2017-present Chartered to Albatros Expeditions.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

The King of the Arctic<br />

Gaby Pilson, Hiking Master & Expedition Guide<br />

Polar bears are the veritable king of the Arctic, despite their often elusive nature in front of human visitors.<br />

But, despite their cute, cuddly, and charismatic appearance, polar bears are fantastically well-adapted to live<br />

in their harsh Arctic landscape. Here are some great fun facts about polar bears:<br />

1<br />

Although those cute and cuddly little polar<br />

bear cubs look shiny and white in photos, polar<br />

bears are actually black! Polar bears have black<br />

skin with a thick coat of transparent fur rather<br />

than the white fur and skin we’ve always<br />

imagined. The black skin helps the bear absorb<br />

sunlight and retain heat in cold arctic<br />

conditions. Polar bear fur contains no white<br />

pigment and simply appears white because of<br />

how sunlight is reflected off of the bear. This<br />

fur is critical for a polar bear, as it allows them<br />

to hunt while staying well-camouflaged among<br />

snowdrifts.<br />

3<br />

Polar bears are patient hunters. Instead of<br />

chasing prey, they sit and wait for hours or<br />

days at seal breathing holes in the ice until the<br />

opportune moment arises. Seals surface every<br />

five to fifteen minutes at these breathing<br />

holes, so polar bears need to be ready at a<br />

moment’s notice. Luckily, polar bears can use<br />

their acute sense of smell to stalk prey without<br />

expending too much energy. Polar bears will<br />

sniff out a seal from up to a mile away and<br />

through the sea ice, so they can sit and wait by<br />

the right breathing hole. These bears show us<br />

that laziness can, indeed, be a virtue.<br />

Page 8<br />

2<br />

These<br />

graceful bears can be difficult to study in<br />

the wild, as harsh conditions and remote<br />

locales conspire against scientists. Fortunately,<br />

scientists have developed a new technique<br />

that allows them to extract DNA from polar<br />

bear footprints. Using just two tiny samples of<br />

snow from a polar bear footprint, scientists in<br />

Svalbard were able to extract DNA from the<br />

bear and its most recent seal-based meal. The<br />

scientific community hopes that this new<br />

technique can help contribute to research on<br />

polar bears and help make tracking and<br />

monitoring the animals more accurate and<br />

efficient.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

4<br />

After<br />

a long winter in a snow den, polar bear<br />

mothers emerge from their winter homes into<br />

the spring sunshine with up to three cubs.<br />

Although cubs emerge from the den about the<br />

size of a small dog, when they are born, they’re<br />

just 30cm (1ft) long and weigh only 450g (1lb).<br />

Newborn polar bear cubs are blind, toothless<br />

and completely dependent on mum for food<br />

and warmth. They nurse on their mother’s milk<br />

(which is nearly 30% fat!) to help them grow<br />

quickly. Polar bear cubs will continue nursing<br />

for nearly two years until they’re ready to start<br />

hunting and eating seals alongside their<br />

mothers.<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

Bears & Belugas in Billefjord<br />

24 June 2019 – Billefjord & Adolfbukta<br />

Today, the true ‘Albatros Expedition’ around<br />

Spitsbergan began. As the Ocean Atlantic pulled into<br />

Billefjord, staff and guests, alike, were greeted by over<br />

30 beluga whales swimming along the ice edge. A huge<br />

gift for all spectators, and a fantastic way to kick off<br />

the voyage, the sight of these beautiful beings is one<br />

we won’t soon forget. While some guests witnessed<br />

the beluga pods while enjoying their tea and breakfast<br />

in the Vinland Restaurant, others were up on deck in<br />

the elements, embracing and enjoying the wildlife<br />

show and the surrounding Arctic scenery.<br />

The beluga whale is one of only three whales that<br />

reside in the cold Arctic waters all year-round. They<br />

have adapted physiologically to be fantastic navigators<br />

in their ice-ridden environment with and have honed<br />

their survival abilities to take on the long, dark Arctic<br />

winters. With a strong dorsal ridge, in place of a top<br />

fin, these whales are capable of swimming under the<br />

ice without getting caught up, an advantage for a<br />

species that spends much of its time bumping up<br />

against the ice in search of breathing holes in the cold<br />

winter months.<br />

From the <strong>Voyage</strong> <strong>Log</strong><br />

Page 9<br />

© Gaby Pilson<br />

Once we finished up with our mandatory briefing, we<br />

snuck in a quick boot party to outfit us all with the<br />

rubber boots that we’ll need to stay dry during our<br />

upcoming landings. After the boot part, lunch came<br />

and went, and we soon made our way down to the<br />

gangway for our first excursion of the voyage: a<br />

zodiac cruise around Adolfbukta.<br />

During our zodiac cruise, we managed to spot, once<br />

again, the polar bear from our earlier sighting.<br />

Although our early views of the bear showed it<br />

sleeping soundly, after a short while, the bear got up<br />

for a stretch and a quick jaunt across the remaining<br />

fast ice, perhaps in search of its next meal. One<br />

walrus, and thousands of birds later, however, we<br />

were on our way back to the ship for an actionpacked<br />

evening of lectures, recap, cocktails with the<br />

captain and a scrumptious dinner to wrap up a<br />

fantastic day in the Arctic.<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

After this brilliant beluga encounter, the Ocean<br />

Atlantic maintained its position as we came across our<br />

first polar bear sighting of the voyage. The ship was<br />

already placed in a great viewing position, so everyone<br />

could hurry to the outer decks for a view of the<br />

Arctic’s apex predator. Soon enough, however, our<br />

furry friend settled in behind some rocks for a snooze<br />

in the sun, so we carried on with our scheduled<br />

programming and participated in a number of<br />

mandatory briefings for our time in the far north.<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

What Makes an Expedition Guide?<br />

Brian Seenan, Lecturer (Geology) & Expedition Guide<br />

A good expedition guide wants you to enjoy as much as of your<br />

destination as possible. You’ve chosen it carefully and you’re<br />

hungry for information: what do penguins eat, what kind of bird<br />

is that, is that a volcano, why are beluga whales white, does the<br />

sea go all the way around that island? So, we’d better be ready.<br />

Page 10<br />

“<br />

We each have a personal style and<br />

specialisation, but one thing unites us all:<br />

our curiosity for the natural world.<br />

”<br />

We find it so fascinating, we do it for a job. If we’re not guiding,<br />

you’ll find us checking out new and interesting places and<br />

things. Every day, we look forward to learning something new,<br />

like how people lived 5,000 years ago or how seals can delay<br />

gestation, so they only return to shore once to give birth and<br />

mate. This kind of thing fascinates us all.<br />

We want to share this stuff with you, so expect us to be<br />

enthusiastic. We’ll fess up if we don’t know every answer, but<br />

we’ll aim to find it – we don’t like uncertainty any more than<br />

you. We enjoy being with people, and talking about what we<br />

see and feel, even if it’s 2 o C below, with a biting wind.<br />

We take care of you, but not like your mom, and we make sure<br />

you don’t fall out of the Zodiac trying to get a perfect shot of a<br />

puffin. We take courses to drive our Zodiacs well. We learn first<br />

aid, so we can handle the unexpected.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

More than anything, we want you to enjoy your adventure.<br />

Everything is there in front of you - the scenery, the wildlife, the<br />

plants and the geology; as guides, we hope we bring them to<br />

life for you.<br />

© Gaby Pilson<br />

© Gaby Pilson © Gaby Pilson<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

Icy Fjords & Scenic Bays<br />

25 June 2019 – Smeerenburg & Magdalenefjord<br />

Overnight we travelled north through a gradually<br />

fading mist as we anchored in Smeerenburgfjord, a<br />

wide inlet framed by jagged mountains.<br />

Page 11<br />

From the <strong>Voyage</strong> <strong>Log</strong><br />

The mountains are gneisses and granites dating back<br />

about 1 billion years. Despite their age, their form is<br />

a recent phenomenon, a product of glaciation about<br />

27,000 years ago, during the last glacial maximum. A<br />

massive ice sheet, some kilometres thick, covered<br />

the northern hemisphere and hatched endless<br />

glaciers, which scoured the land. They left the glacial<br />

landforms we learned in school: u-shaped valleys,<br />

hanging valleys, and moraines.<br />

Whalers selected a gently undulating Pleistocene-era<br />

moraine as the centre of their land operations in the<br />

early 1600s. Smeerenburg, literally “Blubber Town,”<br />

was born. Seven Dutch companies and one Danish<br />

company operated ovens to render down whale<br />

blubber for oil. In its heyday, around 200 men<br />

worked here.<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

A small team of seven men successfully<br />

overwintered in 1633-34. The following year was<br />

disastrous, leaving another group of seven men dead<br />

from scurvy due to the lack of vitamin C in their diet<br />

up in the far north.<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

Arctic terns, eider ducks and guillemots were the<br />

most common birds, though a couple of walrus and<br />

some baby ringed seals popped out of the water and<br />

passed by, eyeing us with curiosity. The other groups<br />

stayed closer to the remains of the ovens and<br />

listened to different experts explain the history and<br />

makeup of the area.<br />

During lunch we repositioned to Magdalenefjord,<br />

which is usually ice-free thanks to the warming<br />

effects of the Gulf Stream. Cruising along in our<br />

trusty zodiacs, we saw a couple of walrus on the<br />

small peninsula near the fjord’s entrance, but most<br />

guests preferred the prospect of seeing<br />

Wagonwaybreen, the glacier at the head of<br />

Magdalenefjord.<br />

While en route to the glacier, we caught sight of a<br />

seal, multiple pairs of eider ducks, lots of guillemots<br />

and the odd tern dipping into the water for a small<br />

fish. A change in cloud cover and freshening of the<br />

wind reminded us that we are in the Arctic. The<br />

temperature dropped by at least 10 o C. It made<br />

sense to retreat to the Ocean Atlantic, to wrap up an<br />

exciting day in Svalbard.<br />

In a world removed from the whalers’ bleak<br />

existence, we scanned for polar bears from the<br />

comfort of M/V Ocean Atlantic before heading to<br />

land, though the constantly changing weather gave<br />

us insight into how difficult life must have been<br />

some 400 years ago.<br />

Some of us enjoyed a fast walk to one end of the<br />

plain, giving us the opportunity to see some bird life<br />

on the water.<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

Ice is Nice – Glacier Fun Facts<br />

Gaby Pilson, Hiking Master & Expedition Guide<br />

Glaciers have, quite literally, shaped our world. Without glaciers, the rolling hills and wide valleys we know<br />

today would look very different, but it turns out that these icy giants have a much longer and more storied<br />

history than many of us would initially suspect. Here are some of the best fun facts about glaciers:<br />

2<br />

4<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

Glaciers are formed by snowflakes. Although it’s<br />

crazy to think that a tiny snowflake can create<br />

something as large as a glacier, without snow,<br />

glaciers would never exist in the first place. To<br />

form a glacier, massive amounts of snow must<br />

accumulate and persist in a single location all<br />

year-long for hundreds, if not thousands of<br />

years. During this time, the individual snowflakes<br />

found in the snowpack change in a process<br />

known as snowflake metamorphosis, where<br />

individual ice grains fuse together and get bigger<br />

and air bubbles get smaller. Once the icepack<br />

builds up enough mass to start flowing downhill,<br />

then voila! We have a glacier.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

1<br />

3<br />

Page 12<br />

Not just anything can be a glacier. In fact, there’s<br />

a size requirement that a piece of ice has to<br />

meet to become a glacier. Anything considered a<br />

glacier must be at least 0.1 km 2 (nearly 25 acres)<br />

in area to be worthy of the name. Although<br />

there’s a minimum size requirement to be<br />

considered a glacier, there’s no upper limit to<br />

glacierhood. The longest glacier on earth is the<br />

Lambert Glacier of Antarctica, which measures<br />

out to some 434 km (270 mi) long. The world’s<br />

largest non-polar glacier is the Fedchenko<br />

Glacier of Tajikistan, which measures a<br />

respectable 77km (48mi) long.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

Glaciers are found all over the world, not just in<br />

the polar regions. While the majority of glaciers<br />

and glacial ice is concentrated in high northern<br />

and southern latitudes, glaciers are found even<br />

near the equator, such as on Mount Kilimanjaro<br />

in Tanzania and in the mountains of Ecuador.<br />

That being said, about half of the world’s<br />

200,000 glaciers are found in one place: Alaska.<br />

There, glaciers cover a whopping 72,500 km 2<br />

(28,000 mi 2 ) of the US state’s total area. That’s a<br />

lot of ice.<br />

Glaciers are basically really, really, really slow-moving rivers. To be considered a glacier, a large mass of ice<br />

must be physically moving downhill. This movement downhill is driven by gravity and is the main reason<br />

why glaciers also act as major agents of erosion. Since glaciers move downhill, they often remove and<br />

transport large boulders and chunks of rock, depositing them much further downhill then where they<br />

started.<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

Into the Ice<br />

26 June 2019 – Northwest Spitsbergen<br />

From the <strong>Voyage</strong> <strong>Log</strong><br />

Although we were at anchor for most of the evening,<br />

which provided us with an opportunity to get a solid<br />

night of sleep, soon after breakfast, the Ocean<br />

Atlantic made its way north, out of our safe<br />

anchorage in Magdalenefjord and into the ice.<br />

Page 13<br />

The sea ice in Svalbard is a magical place. In the north<br />

of Svalbard, only the bravest and hardiest of ships<br />

journey to the edge of the ice, while even fewer<br />

actually manage to venture into the pack ice itself.<br />

For those who do, however, the experience is surreal<br />

– densely packed ice as far as the eye can see create<br />

the perfect environment for a number of marine<br />

mammals that rely on the ice for a place to rest, a<br />

place to hunt, or both.<br />

While the sheer experience of sailing into the ice is a<br />

worthy enough reason to head north, like any true<br />

expedition, we travelled into the world of ice and<br />

snow for another chance to see the ever-elusive king<br />

of the arctic: the polar bear. Although we didn’t<br />

manage to spot any polar bears, just an hour or so<br />

into our ice-filled adventure, we spotted a trio of<br />

walruses, resting casually on a piece of drift ice.<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

Soon enough, however, we were back outside, but<br />

this time, to enjoy the scrumptious arctic barbecue,<br />

compliments of Chef Indra and his talented team.<br />

Braving the polar conditions once again, we<br />

bundled up in our many jackets so we could enjoy<br />

our lunch on the outer decks.<br />

Once lunchtime was all but a distant memory, it<br />

was time for our afternoon activity: a once-in-alifetime<br />

zodiac cruise through the pack ice. With<br />

our trusty zodiacs breaking through small floes of<br />

brash ice, we managed to get up close and personal<br />

with the frozen ocean, before the wind and the cold<br />

beckoned us back inside to the comfort of our ship<br />

once more.<br />

If all of that adventure wasn’t sufficient, soon<br />

enough, we gathered back up in the mudroom for<br />

the ultimate arctic experience: the Polar Plunge. For<br />

the brave few among us, a quick jump into the icy<br />

waters of northern Spitsbergen was a fantastic way<br />

to end a magical day in the ice.<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

Thanks to our captain’s skills and the walrus’ close<br />

proximity to the ship, we managed to snap some<br />

great photos of these gregarious mammals – tusks<br />

and all. After a while, however, many of us gave in to<br />

the cold, windy conditions, opting instead to head<br />

inside and warm up with a cup of tea as we listened<br />

to a handful of lectures about a variety of Arcticthemed<br />

topics, from glaciology to marine biology.<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

Svalbard: A Breeding Ground for Migrant Birds<br />

Dr. George Swan, Lecturer (Ornithology) & Expedition Guide<br />

Page 14<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

In 1594, when the Arctic was first being explored,<br />

Gerrit de Veer, an officer on a Dutch ship, noticed<br />

something strange. While the mammals he<br />

encountered were both new and bizarre (think: huge,<br />

tusked seals and massive white bears), some of the<br />

birdlife was very familiar. In fact, several species of<br />

geese seemed exactly the same as those he had seen<br />

grazing in the Netherlands during the winter. He<br />

hypothesised in his journal: could these birds winter in<br />

the Wadden area and summer in the Arctic? De Veer<br />

knew one thing to be certain, however: they certainly<br />

tasted similarly.<br />

We now know that de Veer’s tentative observation<br />

was spot-on and that the birds he encountered were<br />

probably Brent geese (Branta bernicla) who do,<br />

indeed, winter on the eastern coasts of the North Sea<br />

but spend the summer months breeding in the Arctic.<br />

They make their journey down south and up north<br />

every year and, in doing so, join a whole host of other<br />

migratory birds that make use of Svalbard’s short, but<br />

highly productive, breeding season.<br />

Although the geese arrive to forage on the mosses,<br />

saxifrages and other terrestrial plants, it is the<br />

productivity of the inshore waters and surrounding<br />

seas that draws the biggest crowds. Millions of<br />

seabirds arrive from the Barents Sea and the North<br />

Atlantic to breed on Svalbard’s cliffs and feast on the<br />

zooplankton that blooms in the summer’s 24-hour<br />

daylight. Some come from even further afield; Arctic<br />

terns breed on the coastal flats of Svalbard after<br />

making a staggering journey from their winter foraging<br />

grounds off the Antarctic coast.<br />

Although the summer season is short, and birds must<br />

hurry through the courtship, laying, incubation and<br />

chick rearing processes before the cold weather<br />

returns, those that time it right will head south in<br />

August with that year’s young following close behind.<br />

In acknowledgement of the importance of Svalbard for<br />

breeding birds, 65% of its land area is protected as by<br />

National Parks and Reserves, a testament to the<br />

immense biodiversity in the region.<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

Krossfjord Adventures<br />

27 June 2019 – Möllerfjord & 14 Julibukta From the <strong>Voyage</strong> <strong>Log</strong><br />

Page 15<br />

The morning greeted us with clear skies and a<br />

promising forecast. At 06:30, our Expedition Leader,<br />

Berna and his team disembarked the ship to<br />

undertake a scouting mission on the potential<br />

landing site we had chosen for the morning. As soon<br />

as the area was thoroughly scouted, we came<br />

ashore for a beautiful guided walk around the<br />

diverse and intricate Mollerfjord landscape.<br />

The walk was through some rocky terrain, where all<br />

participants had an opportunity to witness some of<br />

the first blossoms of Svalbard’s spring flowers.<br />

Nutrient leaching from the melting snow and ice<br />

provides excellent fertilizer for the ground below.<br />

These flowers are adored by the Svalbard reindeer,<br />

who also made an appearance this afternoon and<br />

provided an excellent encounter for the guests on<br />

shore.<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

After a fantastic morning, we started our afternoon<br />

with a zodiac cruise along the ridged sedimentary<br />

cliff line adjacent to a breathtaking glacial front,<br />

known as the 14 th of July Glacier (Fortjende<br />

Julibreen) - a significant and beautiful glacier that<br />

got its name from the French national holiday.<br />

Here, we were able to get a close-up view of the<br />

nesting sea birds in the area. There were guillemots,<br />

(both black and Brunnich’s), barnacle geese,<br />

glaucous gulls, kittiwakes, and even a few pairs of<br />

the charismatic Atlantic puffin! As the cruise<br />

continued, the guests got the chance to see a<br />

handful of Svalbard reindeer, sprinkled along the<br />

lichen covered and flower blossoming hillside.<br />

These reindeer are genetically unique to Svalbard<br />

and can be identified by their white fur and often<br />

long antlers. As the afternoon came and went, the<br />

wind picked up and zodiac riders held onto their<br />

seats as the expedition team brought everyone<br />

safely back to the Ocean Atlantic.<br />

After all the guests were onboard, thawed-out and<br />

dry, Lars (Assistant Expedition Leader and<br />

Ornithologist) held a lecture on the longest<br />

migratory species on the planet - the Arctic Tern.<br />

We wrapped up the evening with the daily recap<br />

and plans for tomorrow. Dinner was served while<br />

ship cruising along some incredible glacier fronts as<br />

we worked our way through the night to Ny-<br />

Ålesund, which we planned to make a landing at<br />

and explore first thing in the morning.<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

A Love Story<br />

Gregers Gjersøe, Snowshoe Master & Expedition Guide<br />

Anna Charlier and Niels Strindberg were very much in<br />

love in the spring of 1897. Their passion was music and<br />

they often played together; Anna played the piano<br />

while Niels played the violin. But, Niels also had<br />

another passion – his dream to fly to the geographical<br />

North Pole in a hydrogen balloon.<br />

After many years of effort, Niels’ dream was more<br />

than just a fantasy, however, it was an adventure<br />

waiting to happen. Eventually, a three-man crew,<br />

including Niels, Knut Frænkel, and August Salomon<br />

Andree, were ready to set off on the expedition of a<br />

lifetime in their trusty balloon, The Eagle.<br />

In July of 1897, the trio sailed to Danskøya, a little<br />

island in the northwestern part of Svalbard, and<br />

prepared their balloon for the attempt. Although his<br />

working hours were preoccupied with his upcoming<br />

journey while waiting, Niels read a book to pass the<br />

time. The bookmark he used was a card made by<br />

Anna, which showed the three men flying in a balloon<br />

and she had drawn herself. On the bottom of the card<br />

she wrote: “To where I cannot follow”. In his pocket,<br />

Niels kept her portrait and around his neck he wore a<br />

gold heart, complete her picture and a lock of her hair.<br />

On July 11, 1897, the trio took off from their little<br />

island. After the takeoff, the balloon started spinning<br />

and plunged toward the sea. Panicking, the crew<br />

ejected more than 200 kg of ballast, causing the<br />

balloon to fly too high and disappear behind the<br />

clouds. No one heard anything from the trio for the<br />

next thirty-three years…<br />

According to Andree’s calculations, the hydrogen<br />

balloon could stay afloat for at least 30 days, but the<br />

journey came to an end after just 65 hours. The three<br />

men had landed less than a third of the way to the<br />

North Pole, and now had a long way to walk on the ice<br />

back to Svalbard. The trio packed their sledges, but<br />

they were very heavy, making it difficult to walk more<br />

than a few kilometres at a time on the polar ice. Some<br />

days they worked hard for more than 10 hours, but<br />

they made no progress. In fact, they were moving<br />

further and further north, despite their best efforts,<br />

thanks to the drifting ice.<br />

Along the way, Niels kept writing to Anna. On July 24,<br />

1897, he wrote his last letter – a birthday<br />

© Gaby<br />

cardPilson<br />

for<br />

Anna. In it, he wrote that he was in the best of health<br />

and that she didn’t need to worry about the<br />

expedition.<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Page 16<br />

He promised that they would be make it home in<br />

the end. But, due to the drifting ice, Niels was<br />

constantly moving further away from Anna and<br />

toward the North Pole he so desperately wished to<br />

fly to.<br />

Eighty-eight days after they started, the three men<br />

finally made it to a small and isolated island called<br />

Kvitøya by floating on an ice floe. After only a few<br />

days on Kvitøya, all the three men died in October<br />

1897, although no one knows why.There are many<br />

different theories: carbon monoxide poisoning,<br />

polar bear attack, and scurvy, among others.<br />

But, it was only after ten years that Nils was<br />

declared dead. Two years later, Anna married the<br />

Englishman Gilbert Hawtrey, a 38-year-old French<br />

teacher. At the wedding Anna told Gilbert that she<br />

loved him, but her heart belonged to Niels.<br />

Finally, after thirty-three years (1930), the remains<br />

of the three explorers where found at Kvitøya, along<br />

with all their equipment. Niels’ letters to Anna were<br />

found in the camp and, after some examination,<br />

were sent to Anna. The bodies of the three<br />

explorers were brought back to Sweden, where<br />

thousands of people came to welcome them home.<br />

Anna died when she was 78 years old and is buried<br />

in Torquaq. Although she shares the grave with her<br />

husband, Gilbert Hawtrey, there is no heart in her<br />

body.<br />

The 4 th of September 1947 would have been Nils<br />

Strindberg`s seventy-seventh birthday. In the early<br />

morning, without seeking permission from the<br />

authorities, Nils brothers secretly carried out Anna<br />

Charlier’s final wish. After she died, her heart was<br />

operated out of her body and cremated. Without<br />

involving anyone, they opened Nils Strindberg`s<br />

grave and lowered a small silver chest into it. The<br />

chest held Anna Charlier’s heart, a final act<br />

demonstrating the love she had for a wanderlustfilled<br />

arctic explorer.<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

Page 17<br />

The Northernmost Settlement<br />

28 June 2019 – Ny-Ålesund & Ny-London From the <strong>Voyage</strong> <strong>Log</strong><br />

However, despite its coal mining background, Ny-<br />

Ålesund is one of the most important sites in the<br />

history of exploration of the North Pole. From here,<br />

Roald Amundsen vied with Richard Byrd to be first to<br />

fly over the North Pole. Byrd’s version of events<br />

remains contested, but Amundsen successfully<br />

crossed the pole with an Italian crew, provoking an<br />

argument as to which country should take the<br />

plaudits for the expedition.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

Ny-Ålesund’s scenery can only be described as<br />

dramatic - open vistas over Kongsfjord, jagged<br />

mountains topped with sandwich-neat layers of<br />

sediment, and glaciers inching their way to their<br />

inevitable finale on the fjord. What more could you<br />

ask for?<br />

These days, though, Ny-Ålesund is populated only by<br />

a group of international researchers, who use the<br />

town’s northerly location to study vital aspects of the<br />

Arctic’s environment, all of which is coordinated by<br />

the Norwegian Polar Institute.<br />

Few places have such incredible scenery, so Ny-<br />

Ålesund is much different than many of our homes,<br />

though it is somewhat typical of an Arctic settlement,<br />

with its combination of colourful houses and buildings<br />

sitting on top of a raw, barren landscape of gravel and<br />

tundra.<br />

The juxtaposition of the two is both breath-taking and<br />

intriguing, though we took it all in stride; we even<br />

handled disembarking on a quay like professionals: no<br />

beach, no wet landing. It was like a tightrope walker<br />

saying, “Look ma’, no hands!”<br />

Although Ny-Ålesund grew up on coal, only the<br />

remnants of mining remain: the old coal grading<br />

plant, a disused railway track, and a wonky train that<br />

lugged coal from 1917 to 1958, now restored and<br />

going nowhere.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

Soon enough, however, it was time to leave Ny-<br />

Ålesund behind. During lunch we repositioned to Ny-<br />

London on the other side of the fjord for a leisurely<br />

walk in the tundra.<br />

As we walked across tundra, we saw reindeer grazing<br />

in the distance, ptarmigans in flight, and snow<br />

buntings foraging on the ground At the lake, we were<br />

treated to some good views of nesting red throated<br />

divers, long–tailed ducks and purple sandpipers, while<br />

overhead we saw arctic terns and a solitary long<br />

tailed skua.<br />

All the while, evidence of a failed mining operation<br />

was more than plentiful, with an abundance of old<br />

machinery, railroad tracks, and other such miningrelated<br />

equipment paying homage to what was once<br />

a major economic focus of the region.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

Polar Diplomacy<br />

Thomas Bauer, Lecturer (Historian) & Expedition Guide<br />

The polar regions of the high Arctic and the Antarctic<br />

are some of the least explored parts of our planet<br />

Earth. Compared to the rest of the world, these<br />

regions have seen relatively few human inhabitants<br />

and their ecology is dominated by snow, ice and<br />

wind. The main inhabitants of these regions are polar<br />

bears, walrus, seals, whales, birds and reindeer in the<br />

high Arctic; and penguins, whales, seals and large<br />

flying seabirds, such as the wandering albatross, in<br />

Antarctica.<br />

The Svalbard Treaty<br />

The Svalbard (formerly known as Spitsbergen)<br />

archipelago and the Antarctic continent have one<br />

important commonality: they have never had a<br />

permanent human population. From this fact arose<br />

the interesting question of who owns these lands of<br />

ice and snow?<br />

In Svalbard this issue was settled on 9 February 1920<br />

when the Treaty Relating to Spitsbergen (Svalbard)<br />

Page 18<br />

was signed in Paris. The archipelago had previous<br />

been declared terra nullius or “no-man’s-land”<br />

because no country had laid claim to it. The Treaty<br />

recognized the sovereignty of Norway over all of<br />

Svalbard but at the same time declared that nationals<br />

of all the other signatory countries (USA, UK with its<br />

dominions, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan,<br />

Netherlands and Sweden) would have equal rights to<br />

those of Norwegians to carry out commercial or<br />

mining operations around the archipelago.<br />

The Treaty also specified that this was to be a region<br />

of peace where, according to Article 9: ‘Norway<br />

undertakes not to create nor to allow the<br />

establishment of any naval base in the territorial<br />

waters of Svalbard’. Thus, was created the first<br />

agreement between states to allow several countries<br />

to enjoy the privilege of using existing resources in<br />

Svalbard while at the same time maintaining the<br />

region as a place of peace.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

© Gaby Pilson<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

Becoming an Expedition Guide<br />

Gregers Gjersøe, Snowshoe Master & Expedition Guide<br />

Page 19<br />

Back in 1999, I crossed Greenland on skis with two of<br />

my Danish friends. When we finally made it to the top<br />

of the ice cap, we decided to celebrate by flying the<br />

Danish and the Greenlandic flag. Unfortunately, we<br />

ended up placing the Greenlandic flag upside down<br />

because none of us was sure which way was correct...<br />

During the remainder of the expedition, as we made<br />

our way down from the top of the ice cap, I started<br />

thinking more about why and how three Danish guys<br />

could possibly know so little about Greenland, despite<br />

the fact that it’s a part of the Kingdom of Denmark.<br />

When I returned home, I decided to learn all I could<br />

about Greenland and the polar regions, travelling<br />

extensively, not only to Greenland, but throughout the<br />

Arctic and the Antarctic. The polar areas became my<br />

passion and have been for the last twenty years. I<br />

became so fascinated by the polar regions, that I<br />

wanted to share my knowledge and love for these<br />

places with other people. There is so much to love and<br />

experience in the polar regions, from great scenery<br />

and wildlife to the culture of the peoples who have<br />

populated the Arctic since time immemorial.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

I haven’t always worked in the polar regions, though.<br />

Since childhood, I was very interested in navigation,<br />

aerodynamics, metrology and aviation. I acquired my<br />

pilot’s license in 1985 and worked as a commercial<br />

pilot for Scandinavian Airlines during a 30 year career.<br />

There, I was able to satisfy all of my interests while<br />

learning how to work as part of a team, bringing the<br />

aircraft from point A to point B in the safest way<br />

possible.<br />

After ending my pilot career, I took up yet another<br />

dream of mine that had occupied my mind since<br />

crossing Greenland. In Danish schools, there is very<br />

little focus on the history and cultures of Greenland<br />

and the Faroe Islands; thus, there is very little<br />

awareness within the Danish population about these<br />

countries. I wanted to create a much better awareness<br />

and, therefore, I started the Polar School<br />

(Polarskolen).<br />

The school is run as a non-profit organization with a<br />

board of nine members. I am chairman of the board<br />

and there are members from the Danish government,<br />

from Greenland, the Faroe Islands as well as teachers.<br />

We have received funding from the Royal Crown<br />

Prince Frederik and his wife, Crown Princess Mary.<br />

Now, I travel Denmark, visiting schools with our<br />

educational materials. Presently we teach 7 th graders,<br />

but we are working towards having materials for 1 st<br />

graders and 4 th graders.<br />

Based on my background and experience in aviation<br />

and in the polar regions, I could not think of a better<br />

way to combine my passions for the Arctic and the<br />

Antarctic then to become Expedition Guide. These<br />

days, I spend five weeks of the summer in the Arctic<br />

and five weeks of the winter in the Antarctic, so I can<br />

show our guests all the places that I truly love.<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

The Final Days<br />

29 June 2019 – Alkhornet & Ymerbukta<br />

Page 20<br />

From the <strong>Voyage</strong> <strong>Log</strong><br />

Although the midnight sun and the evening activities<br />

kept us up much too late the preceding night, it’s only<br />

fitting that we to got up early to make the most of our<br />

last full day in Svalbard. After some early morning<br />

pastries and a hearty breakfast, we got our cold<br />

weather gear back on to head out for a final landing at<br />

Alkhornet.<br />

High winds and cold temperatures provided us with a<br />

true arctic experience, as we bundled up for the<br />

bumpy zodiac ride to the landing site. As soon as we<br />

completed the steep, but thankfully short, climb up to<br />

the tundra-covered plateau, however, we were<br />

treated to some stunning views of a staggeringly tall<br />

bird cliff and the surrounding mountain landscape.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

Lunch came and went, and soon enough, it was time<br />

for the afternoon zodiac cruise at Ymerbukta. Our<br />

trusty zodiacs glided through the water, treating us to<br />

stunning views of the surrounding mountains, glaciers,<br />

and tundra-filled landscape.<br />

All in all, Alkhornet and Ymerbukta proved to be a<br />

glorious ending to a fantastic set of excursions during<br />

our voyage around Svalbard. Although we’d love to<br />

stay longer, life has other plans in store for many of us,<br />

so we waved a fond farewell to Svalbard and all of the<br />

adventures its wonderful landscape holds as we<br />

zoomed back to the ship for the final time.<br />

© Gaby Pilson<br />

As we head out on our final guided walk of the trip, we<br />

were treated to excellent views of the Svalbard<br />

reindeer (Spitsbergen’s charismatic ungulate), while a<br />

few of us even managed to enjoy a quick sighting of<br />

the ever-elusive arctic fox.<br />

Whether you were on the lookout for foxes, or were<br />

mesmerised by the abundant wildflowers sprawled<br />

across the tundra, it was hard, however, to miss the<br />

tens of thousands of nesting seabirds high up on the<br />

cliffs of Alkhornet. The cacophony of sounds of each of<br />

these birds as they try to find their nest is one that<br />

we’d be hard-pressed to forget.<br />

Once back on the ship, we enjoyed our last afternoon<br />

tea, a celebratory evening of cocktails and fine dining,<br />

which was capped off by a decadent spread of<br />

chocolate-based deserts to wrap up an amazing<br />

culinary experience, thanks to the talents our head<br />

chef, Indra.<br />

Finally, we packed our bags, organized our belongings,<br />

and prepared for disembarkation the next day and our<br />

journeys home - a bittersweet adieu to the Ocean<br />

Atlantic after a fantastic voyage in Svalbard.<br />

Like all good things, however, our final landing came<br />

to an end. After an equally exciting zodiac ride, we<br />

were finally back on the ship for a well deserved lunch<br />

and break before the afternoon’s activities.<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

A Brief History of the Zodiac<br />

Steve Traynor, Zodiac Master<br />

In expedition cruising, the most important tool we use is the Zodiac inflatable boat. These manoeuvrable,<br />

reliable, robust vessels are the workhorse of the expedition cruise industry, from the north of Svalbard to<br />

the southern end of the Antarctic Peninsula. They have a long history – as you can see from the stages<br />

below, many different inventions needed to come together to create the craft we use today.<br />

Page 21<br />

© Renato Granieri Photography<br />

1838 Charles Goodyear (USA) discovered the process for vulcanising rubber (a US patent was granted<br />

in 1844) – this process is used for hardening and strengthening rubber.<br />

1843 Goodyear’s process was stolen by Thomas Hancock (UK) using the process of reverse<br />

engineering; less controversially, Hancock invented the “masticator” – a machine for re-using<br />

rubber scraps – this made the rubber industry much more efficient.<br />

1845 The first successful inflatable boat (Halkett boat) was designed by Lieutenant Peter Halkett<br />

(UK), specifically for Arctic operations. Halkett Boats were used by the Orcadian explorer, John<br />

Rae, in his successful expedition to discover the fate of the Franklin Expedition.<br />

1866 Four men made the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean from New York to Britain on a threetube<br />

inflatable raft.<br />

1896 The original Zodiac company was founded by Maurice Mallet (France) to produce airships.<br />

1909 The first outboard motor was invented by Ole Evinrude in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.<br />

1912 The loss of the Titanic and subsequent shipping losses during World War 1 proved the need for<br />

inflatable rafts for use as supplementary lifeboats.<br />

1919 RFD firm (UK) and the Zodiac company (France) started building inflatable boats.<br />

1934 The airship company, Zodiac, invented the inflatable kayak and catamaran<br />

1942 The Marine Raiders – an elite unit of the US Marine Corps – used inflatable boats to carry out<br />

raids and landings in the Pacific theatre.<br />

1950 Alain Bombard first combined the outboard engine, a rigid floor and an inflatable boat (built by<br />

the Zodiac company).<br />

1952 Alain Bombard crossed the Atlantic Ocean with his inflatable; after this, his good friend, the<br />

famous diver Jacques-Yves Cousteau, started using them.<br />

1960 Zodiac licensed production to a dozen companies in other countries because of their lack of<br />

manufacturing capacity in France.<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

Home Again<br />

30 June 2019 - Longyearbyen<br />

After last night’s end-of-voyage festivities, we<br />

awoke much too early for our final morning on the<br />

Ocean Atlantic. As the Ocean Atlantic pulled into its<br />

anchorage in Longyearbyen, we started the process<br />

of leaving behind the ship and the people we’ve<br />

come to know so well over the past week.<br />

Our bags were packed and stowed in the corridors,<br />

ready for our early-morning busses and flights back<br />

to Oslo, Copenhagen, and everywhere in between.<br />

After seven whole days immersed in the landscapes<br />

and amongst the wildlife of the Arctic, it was time<br />

to return home or to wherever our life’s journeys<br />

bring us.<br />

And so – farewell, adieu, and goodbye. Together we<br />

have visited and incredible and vast wilderness. We<br />

have experienced magnificent mountain vistas,<br />

seen icebergs roll and crack, felt the power of the<br />

elements and seen how quickly they can change.<br />

We enjoyed wonder food and comfortable<br />

surroundings aboard the Ocean Atlantic. We<br />

Page 22<br />

From the <strong>Voyage</strong> <strong>Log</strong><br />

boarded zodiacs and cruised through icy fjords at<br />

the end of the Earth. We have shared unique<br />

moments, held engaging conversations, and<br />

laughed together over beers and coffees. We’ve<br />

made new friends and experienced the power of<br />

expeditionary travel.<br />

We hope the expedition team has helped make this<br />

the trip of a lifetime - one that will persist in your<br />

memories for weeks, months, and years, to come.<br />

Although we must say good-bye to these places we<br />

have come to know and love, it is a fond farewell as<br />

we are all true ambassadors for the Arctic and all<br />

the beauty it holds.<br />

On behalf of Albatros Expeditions, our captain and<br />

crew, the expedition team, and everyone else who<br />

helped make this journey a resounding success, it<br />

has been a pleasure travelling with you. We hope<br />

that you will come back and experience these<br />

wonderful places with us once again!<br />

© Yuri Choufour<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5

A Final Note…<br />

Page 23<br />

As any good expedition comes to a close, many of us experience the<br />

effervescent excitement that comes when we immerse ourselves<br />

completely in an adventure. Although we all came into this voyage with<br />

our own expectations and personal motivations, on the ship, we quickly<br />

learned that the best plan is the one that we end up doing.<br />

While weather and the landscape<br />

can conspire against us in the<br />

northern latitudes, the right mindset<br />

can make all of the difference.<br />

Wind, rain, sleet, and snow make<br />

no difference when we come<br />

prepared for an adventure and all<br />

the excitement it holds. Whether<br />

you saw what you came for or you<br />

experienced something else<br />

entirely, when you set out on an<br />

expedition, you come for the<br />

mountains and the wildlife, but<br />

stay for people and places you<br />

meet along the way.<br />

Although we all eventually have to<br />

leave behind our beloved Ocean<br />

Atlantic, there are always a few<br />

things we can take home from an<br />

expedition:<br />

• An acceptance and<br />

embracement of adversity and<br />

uncertainty when the natural<br />

world alters our plans.<br />

• A fondness for the wild and a<br />

strong desire to keep remote<br />

natural locations as beautiful<br />

and free as they can be.<br />

• An insatiable interest in learning<br />

more about the people, places,<br />

and cultures in some of the<br />

most remote parts of the world.<br />

As you unpack you bags, you may<br />

find souvenirs and keepsakes from<br />

your journey. Your camera may be<br />

filled with countless photos,<br />

however blurry, of the many<br />

animals and mountains that have<br />

crossed our paths. At the end of<br />

the day, however, what matters<br />

most is the experience of, the<br />

journey to, and the memories of<br />

these wild and wonderful places.<br />

Best wishes from all of us on the<br />

expedition team as you continue<br />

on with your adventures!<br />

Berna Urtubey<br />

Expedition Leader<br />

Lars Maltha Rasmussen<br />

Assistant Expedition Leader<br />

Thank you for experiencing the Arctic with us at Albatros<br />

Expeditions. We hope to see you aboard the Ocean Atlantic<br />

again in the future!<br />

Steve Egan<br />

Assistant Expedition Leader<br />

23-30 June, 2019<br />

Volume 1, Issue 5