Movement-153

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

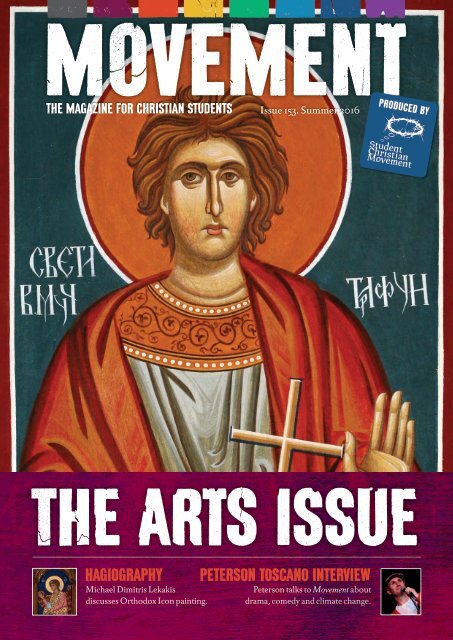

MOVEMENTPRODUCED BY<br />

the magazine for christian students Issue <strong>153</strong>. Summer 2016<br />

the ARTS issue<br />

Hagiography<br />

Michael Dimitris Lekakis<br />

discusses Orthodox Icon painting.<br />

Peterson Toscano Interview<br />

Peterson talks to <strong>Movement</strong> about<br />

drama, comedy and climate change.

SCM is seeking to employ a<br />

new development worker<br />

in Manchester to engage<br />

a generation of university<br />

students with inclusive student<br />

communities and local churches<br />

in the North West of England.<br />

The appeal is being match funded, which<br />

means all donations will be doubled and<br />

ensure even more students are welcomed<br />

into communities that are open, diverse<br />

and committed to justice. Please consider<br />

making an online donation today to<br />

support this work.<br />

Thank you for your support.<br />

contents<br />

Make a donation at www.movement.org.uk/northwest

Pages 2-7 Editorial • COMING UP<br />

• NEWS • international • GROUPS<br />

issue <strong>153</strong><br />

8-9 faith in action<br />

10-11 Interview<br />

With With Peterson Toscano<br />

12-13 the theology of fantasy<br />

By Taylor Driggers<br />

14-15 Hagiography<br />

By Michael Dimitris Lekakis<br />

16-17 The Bard & the bible<br />

By Ellie Wilde<br />

18-19 three perspectives<br />

on music in worship<br />

With Feylyn Lewis, Mark Russ & Sarah Derbyshire<br />

20 Faith & Art<br />

Ruth Naylor<br />

21 Groovement<br />

12-13<br />

10-11<br />

16-17<br />

14-15

Welcome to this issue of <strong>Movement</strong>, which takes a look at the arts.<br />

For many of us, exams (sorry for mentioning the E word!) are just<br />

about beginning to rear their heads at us, and I think that using our<br />

own creativity can be a really relaxing way to spend time between<br />

revision sessions. We might choose a colouring book, playing an<br />

instrument, or appreciating others’ work; through listening to music,<br />

going to an art gallery or reading a book. Prayer is also a good way<br />

for expressing our inner artist: SCM has often been made up of creative types, and<br />

those of us who would consider ourselves ‘artistically challenged’ have discovered<br />

a different kind of creativity through the ways we explore faith.<br />

We are really excited to have an interview with Peterson Toscano; who is a<br />

playwright and actor. He talks about the intersection of faith and sexuality<br />

through plays and workshops, and how he uses the platform that the dramatic<br />

arts gives him in order to talk about his experiences of gay conversion therapy and<br />

get his audiences thinking in a different way.<br />

Another way in which Christians experience art is through icons, and Michael<br />

Lekakis takes us through the Orthodox Church’s use of these and the process<br />

of hagiography. In addition, we have packed this issue with a piece from Taylor<br />

Driggers about fantasy literature and desert spirituality, and a feature on the use<br />

of music in different worship traditions.<br />

As if that wasn’t enough, we are also very pleased to bring the return of the<br />

crossword. I for one am very much<br />

looking forward to having a good go<br />

at this while sat with a cup of tea!<br />

Clare Wilkins<br />

I really hope you all enjoy this<br />

issue. For those of you with exams,<br />

coursework deadlines, vivas, job<br />

interviews and all the things that<br />

come with this time of year – all the<br />

best with these, and I hope that this<br />

issue of <strong>Movement</strong> will<br />

be just what you need<br />

to help you chill out.<br />

the sidebar<br />

SCM office:<br />

Grays Court<br />

3 Nursery Road, Edgbaston<br />

Birmingham B15 3JX<br />

Tel: 0121 426 4918<br />

scm@movement.org.uk<br />

www.movement.org.uk<br />

Advertising<br />

scm@movement.org.uk<br />

Tel: 0121 426 4918<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> is published by the<br />

Student Christian <strong>Movement</strong><br />

(SCM) and is distributed free to<br />

all members, supporters, local<br />

groups, Link Churches and affiliated<br />

chaplaincies.<br />

SCM is a student-led movement<br />

seeking to bring together students<br />

of all denominations to explore the<br />

Christian faith in an open-minded<br />

and non-judgemental environment.<br />

SCM staff:<br />

National Coordinator: Hilary Topp,<br />

Finance and Projects Officer:<br />

Lisa Murphy, Groups Worker:<br />

Lizzie Gawen, Fundraising and<br />

Communications Officer: Ellis<br />

Tsang, Faith in Action Project<br />

Worker: Ruth Wilde, Administration<br />

Assistant: Ruth Naylor<br />

Editorial Team:<br />

Debbie White and Lisa Murphy.<br />

The views expressed in <strong>Movement</strong><br />

magazine are those of the particular<br />

authors and should not be taken<br />

to be the policy of the Student<br />

Christian <strong>Movement</strong>. Acceptance of<br />

advertisements does not constitute<br />

an endorsement by the Student<br />

Christian <strong>Movement</strong>.<br />

ISSN 0306-980X<br />

Charity number 1125640<br />

© 2016 Student Christian<br />

<strong>Movement</strong><br />

Designed by<br />

penguinboy.net &<br />

morsebrowndesign.co.uk<br />

Do you have problems reading <strong>Movement</strong>? If you find it hard<br />

to read the printed version of <strong>Movement</strong>, we can send it to<br />

you in digital form. Contact editor@movement.org.uk

coming up<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> 2016:<br />

Stories of Faith<br />

10–12 JUNE 2016<br />

WOKINGHAM<br />

Group Leaders’<br />

Training<br />

8-9 SEPT 2016, BIRMINGHAM<br />

Are you part of your group committee<br />

for the next academic year? Want to<br />

learn more about making your group the<br />

best it can be? There are two free places<br />

per group, so look out for the booking<br />

form in your mailing and return it to<br />

the office as soon as possible!<br />

For more information about the<br />

training, visit<br />

www.movement.org.uk/events<br />

Join us in the beautiful Berkshire countryside for our mini-festival!<br />

We’ve got an amazing line up, and more speakers and workshops<br />

are being confirmed each week.<br />

Our speakers include Professor David Ford, Padraig O’Tuama,<br />

Revd Rose Hudson-Wilkin, Selina Stone, Richard Goode, Jake<br />

Mahal, Jessica Dalton and Graham Maule from<br />

the Wild Goose Resource Group.<br />

There will be workshops from Christian<br />

Aid, CAFOD, Church Action on Poverty<br />

and The Esther Collective, as well as live<br />

music from Clutching at Straws and<br />

Mary Anna.<br />

SCM FRIENDS Gathering:<br />

Wokingham 11 June<br />

Effective<br />

Student Work<br />

Training<br />

8-9 SEPT 2016, BIRMINGHAM<br />

Do you have a Chaplaincy Assistant<br />

or Student Worker joining you this<br />

year? Interested in chaplaincy<br />

work, or have a heart for student<br />

ministry? SCM’s Effective<br />

Student Work training is a twoday<br />

interactive and intense course<br />

that covers everything you need to<br />

know about student work. To find<br />

out more and book your place visit<br />

www.movement.org.uk/events<br />

Come along to meet other SCM Friends and join with students to hear from our speakers at <strong>Movement</strong> 2016: Stories of Faith.<br />

Children welcome! For more details, visit www.movement.org.uk/stories-of-faith<br />

Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter for all the latest updates!<br />

facebook.com/StudentChristian<strong>Movement</strong><br />

@SCM_Britain<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong> Page 3

EWS<br />

New partnership<br />

between SCM and<br />

Greenbelt Festival<br />

SCM is pleased to announce it will become an associate of the Greenbelt<br />

festival. The partnership aims to get more students involved in the festival<br />

this year and provide more student-friendly spaces and content that directly<br />

address issues that students and young adults are passionate about.<br />

‘SCM are really excited to be partnering with Greenbelt,’ said Hilary Topp,<br />

SCM’s National Coordinator. ‘As well as giving a voice to students at the<br />

festival, we want to make sure students find a bit of the Greenbelt spirit near<br />

them all year round, in every city and on every campus.’<br />

‘We’re excited to work together with a grassroots student body that so<br />

closely resonates with our theology, vision and values,’ said Paul Northup,<br />

Greenbelt’s Creative Director. ‘Our hope is that this new relationship helps<br />

strengthen our reach into student communities up and down the country.’<br />

Further details of SCM’s activities at Greenbelt this year will be announced<br />

in due course – keep updated with all the news by following us on Twitter<br />

(@SCM_Britain) or Facebook (StudentChristian<strong>Movement</strong>), or checking<br />

online at www.movement.org.uk<br />

Mourning the<br />

loss of Revd<br />

Dr Andrew<br />

Morton,<br />

former SCM<br />

Scottish<br />

Secretary<br />

SCM is saddened to learn of the death of<br />

Revd Dr Andrew Morton, a former staff<br />

member in the 1950s. Dr Morton, who<br />

died aged 87 on 7 January 2016, joined the<br />

movement in 1953 as Scottish Secretary and<br />

was appointed chaplain at the University of<br />

Edinburgh in 1964.<br />

During the 1950s, SCM had a national<br />

staff team of around 30 secretaries, working<br />

in different regions within universities,<br />

colleges and schools. Dr Morton was one of a<br />

number of ‘travelling secretaries’, who moved<br />

within the region to support and coordinate<br />

grassroots student mission work that included<br />

organising an annual conference in Scotland.<br />

Revd Jim Wilkie, President of SCM<br />

Aberdeen at the time, met Dr Morton at the<br />

Scottish Council in 1953. He said, ‘Andrew<br />

was a highly articulate, theologically well<br />

trained leader who was especially good in<br />

small groups of students such as those we<br />

enjoyed in SCM. All his life he was totally<br />

committed to persuading Christians from all<br />

denominations to modernise their theology<br />

together, and to relate it to social and political<br />

issues. We miss him.’<br />

SCM Friend William Farquhar, who joined<br />

SCM Aberdeen in 1954 and met Dr Morton<br />

during his involvement in the group, said,<br />

‘He was a fine man and throughout a great<br />

supporter of SCM.’<br />

A service for Dr Morton was held at St Giles’<br />

Cathedral in Edinburgh on Thursday 14<br />

January.<br />

Page 4 <strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong>

NEWS<br />

Students<br />

and SCM<br />

members<br />

join Stop<br />

Trident Rally<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> SUMMER 2016<br />

Hundreds of students, including<br />

SCM members, joined peaceful<br />

demonstrations in London on Saturday<br />

27 February, calling on the British<br />

government to scrap the renewal of the<br />

Trident nuclear programme.<br />

Before the march, Christians joined<br />

members of different faiths at an<br />

interfaith service at Hinde Street<br />

Methodist church at 11am. Christians<br />

and Buddhist monks were among the<br />

hundreds of people who packed the<br />

church to hear readings and reflections<br />

on the issues of peace and nuclear<br />

disarmament.<br />

Emma Temple, an SCM member who<br />

attended the event, led the litany at the<br />

interfaith service. She said, ‘I was so<br />

encouraged to see thousands of people<br />

coming together at the Stop Trident<br />

march. It gave me hope that people feel<br />

so strongly about the devastating effects<br />

renewing Trident will have for so many<br />

reasons.’<br />

SCM and Taizé<br />

gathering: a weekend<br />

of learning, reflection<br />

and action<br />

What does it mean to be courageous<br />

and merciful? This was one of<br />

many questions at the heart of<br />

SCM’s gathering in London on 4<br />

– 5 March, in partnership with the<br />

Taizé community and Oasis Church<br />

Waterloo.<br />

More than one hundred people<br />

gathered on Friday evening for a<br />

Taizé service that included Lenten<br />

Prayer around the Cross. Participants<br />

came from different walks of life,<br />

including students and young people,<br />

parents and children, musicians,<br />

churchgoers, and volunteers from<br />

the Taizé community in France.<br />

Around 25 students and young<br />

people met together on Saturday<br />

to hear from Revd Steve Chalke,<br />

founder of Oasis UK, and Brother<br />

Paolo from the Taizé community.<br />

Participants joined volunteers from<br />

Harvest for Hope, a local charity,<br />

to load an articulated lorry with<br />

food and resources that will travel to<br />

Greece and be distributed to refugees<br />

fleeing conflict in the Middle East.<br />

Debbie White, a PhD student who<br />

came to the event, said: ‘I really<br />

enjoyed coming together with<br />

other students from across the UK<br />

in London for the Taizé event.<br />

Throughout the weekend, I felt a<br />

strong sense of being surrounded by<br />

a loving, Christ-centred community<br />

as we shared worship, fellowship<br />

and time together. I took part in so<br />

many discussions about what makes<br />

something a good community and it<br />

was great to see that borne out not<br />

just in our words but in our practice<br />

as well.’<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong> Page 5

International<br />

Student Sunday 2016: SCM Colombia<br />

On 20 February, SCM Colombia celebrated the<br />

Universal Day of Prayer for Students (UDPS),<br />

joining with hundreds of other students and<br />

Christians around the world. The movement in<br />

Colombia is one of the newest affiliated SCMs in<br />

the World Student Christian Federation (WSCF),<br />

created last year at the 35th General Assembly of<br />

the WSCF. It has two branches – one in Bogota<br />

and one in Barranquilla.<br />

We asked Diana Cruz, a member of the movement,<br />

to tell us a bit more about how SCM Colombia<br />

celebrated Student Sunday.<br />

‘Student Sunday was a very important event for<br />

the SCM in Bogota because it was our first official<br />

activity as an SCM. It was celebrated in a small<br />

service on 20 February 2016. Around 15 people<br />

participated and around half of them were college<br />

or school students. We had a photo gallery on the<br />

theme ‘student struggles’ around the world, with a<br />

special emphasis on the struggles in Latin America.<br />

WSCF Europe Staff and Officers’ Meeting<br />

On 2 March I was lucky enough to be able to fly out<br />

to Oslo for four nights in order to attend this year’s<br />

WSCF Europe Staff and Officers’ Meeting.<br />

On the first evening we spent time getting to know<br />

one another, and had a time of meditation and worship,<br />

led by Lutheran minister-to-be Are from Sweden, who<br />

also invited contributions from other participants. I<br />

found this a very helpful space for contemplation and<br />

quiet in the midst of a very busy schedule.<br />

Thursday consisted of educational sessions led by senior<br />

employees from the Communications department at<br />

the World Council of Churches (WCC). We learnt<br />

about how we can use media, and especially social<br />

People who entered the church could see the photos<br />

and spend some time in reflection.<br />

During the service we set up a few stations that used<br />

different symbols and forms of prayer. For example,<br />

we used a mirror in the station about students<br />

around the world to recognise that students share<br />

similar experiences and struggles. To talk about<br />

popular education, we showed participants how to<br />

make an origami crane, symbolising that education<br />

also comes about when we make something.<br />

Even though it was a small group it was a very<br />

meaningful moment to pray for students in our<br />

country, continent and around the world, and we<br />

are glad we could be part of it.’<br />

Student Sunday was also celebrated here in Britain,<br />

with prayers and services being led at All Hallows’<br />

church in Leeds, Holy Innocents Fallowfield<br />

in Manchester, West Park URC, and SCM<br />

Cambridge, among many others. Thank you to all<br />

who participated this year!<br />

media, to our advantage in our SCMs. On Friday,<br />

we had more input from Marianne, the Director of<br />

Communications at the WCC. Francois, an expert<br />

in third sector volunteer management, led us on the<br />

final day. I felt we came away from the sessions with a<br />

better understanding of how to enable and work with<br />

volunteers, and also how to chair meetings successfully.<br />

Overall, it was a very helpful three days. I learnt new<br />

things, networked and enjoyed the food which Gabi<br />

from Slovakia kindly cooked for us. I would highly<br />

recommend WSCF events to all students and staff in<br />

SCM Britain!<br />

Ruth Wilde<br />

Page 6 <strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong>

GROUPS<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> SUMMER 2016<br />

Cambridge Methodist Society<br />

This term has seen some subtle changes to Cambridge<br />

MethSoc. We have been sharing several Friday evenings with<br />

the other local SCM group following the recent re-start of<br />

SCM Cambridge. It has been great getting to know everyone,<br />

and sharing our social evenings shares the work of hosting<br />

while also getting more of us together – a win-win situation!<br />

Our weekly Bible study has looked at topics including the<br />

cultural context in the parables of Jesus and the concept of<br />

God’s omniscience as described by C. S. Lewis. Next term we<br />

will be looking at the Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan.<br />

On the Universal Day of Prayer for Students one of our<br />

members Sarah led the evening service at our local church,<br />

with the help of many of the SCM resources. It was a thought<br />

provoking day, as well as a time of strong fellowship for<br />

students young and old.<br />

The future of the Methodist Society in Cambridge at the<br />

moment is uncertain. The national trend of decline permeates<br />

even to our generation it seems, but we are praying that our<br />

small university community can be inspiring and uplifting to<br />

as many as possible and may spring into new growth.<br />

William Collins<br />

SCM Manchester<br />

This term has been an interesting and thought provoking one<br />

in Manchester as we have had the opportunity to explore our<br />

faith and learn more about social justice issues.<br />

This term we held Eat, Pray, Act evenings where we ate<br />

together and learnt about different social justice issues,<br />

discussing how we might act on them. The issues we focused<br />

on this term included tax dodging and the effects of the palm<br />

oil industry, as we considered how our shopping habits affect<br />

the animals and people in Indonesia and Malaysia.<br />

In February we welcomed Symon Hill as our guest speaker,<br />

talking about his new book The Upside-Down Bible. We were<br />

challenged to look anew at some of the most well-known<br />

bible stories which led to some really interesting discussions.<br />

In March we learnt more about the theology of St Francis as we<br />

welcomed the Franciscans of the First and Third orders to speak<br />

to us about what Francis had to say about the environment.<br />

Overall, this term has been really interesting and we look<br />

forward to what the new term will bring.<br />

Sally Foxall<br />

SCM Leeds<br />

This has been exciting year for SCM Leeds! We<br />

started up again in September after not running<br />

last year, and the group has been really successful.<br />

We’ve been running Taizé services every other<br />

week, which have been great opportunities to<br />

relax and enjoy quieter worship. We’ve also had<br />

excellent workshops from SCM’s Ruth Wilde on<br />

theological reflection, and Matt Carmichael on his<br />

book with Alastair McIntosh, ‘Spiritual Activism’.<br />

This term we have held an interfaith prayer<br />

workshop, took part in activities for Christian<br />

Aid week, and attended the Stop Trident march<br />

in London. We’re also planning a trip to Taizé in<br />

the summer. Please pray that the group will keep<br />

going strong, and that more and more students<br />

will find us. Emma Temple<br />

Birmingham Methodist Society<br />

This term has been quite a packed one for MethSoc! We have<br />

been continuing to hold our weekly meeting with an increased<br />

membership, mixing social action, spending time socialising<br />

and worship. We have had curry nights, joint meetings with<br />

the University Atheist, Secularist and Humanist Society<br />

and we also hosted the Real Junk Food Project. Outside of<br />

our weekly meetings we have continued to run our Food<br />

Exchange Scheme, collecting left over food from campus on a<br />

Friday afternoon and passing it onto the homeless. We’ve also<br />

started a Sunday night Bible Study and have been increasing<br />

our work with CathSoc and AngSoc, holding a joint wine and<br />

cheese night and a board games night, which were a great<br />

success. We are looking forward to the summer term and<br />

everything it has in store!<br />

Rachel Allison<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong> Page 7

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

Refugee<br />

Campaign<br />

Day of<br />

Action<br />

MARK<br />

Going into the event, I was under the<br />

impression that I had a moral duty<br />

to make a difference, to act, in some way or another. I<br />

was also under the impression that I could not make<br />

a meaningful difference on my own. ‘I’ would have to<br />

change into ‘we’ in order for any progress to made. I<br />

may have a moral duty to act in the face of a refugee<br />

crisis, but it is our collective effort, our togetherness,<br />

which will bring about lasting change.<br />

Many issues were raised at the event, which makes it<br />

difficult to single out one specific issue to focus on.<br />

However, my current status as a university student<br />

means I am inclined to write about the issue of<br />

education. Being in higher education and having<br />

gone through a very good comprehensive secondary<br />

school, I know that I am fortunate to be in the<br />

situation I am in. However, I am also adamant that<br />

this shouldn’t be a privilege, but a right.<br />

Many times throughout the day, the problem of<br />

ignorance and media bias (if the conscious spreading<br />

of lies can be counted as bias) was raised. A lack of<br />

information and a warped perception of the refugee<br />

crisis have led to poisonous attitudes in our society;<br />

attitudes based on fear and hate. It is vital that,<br />

On 13th February, students from SCMs in Leeds, Birmingham<br />

and Worcester came together at St Chad’s Sanctuary in<br />

Birmingham to learn about the issues facing refugees. We<br />

heard stories from refugees themselves, learnt about what<br />

we can do, and reflected on what our faith has to say about<br />

how we should treat people who are seeking asylum.<br />

Sarah Derbyshire from Leeds SCM and Mark Birkett from<br />

Birmingham Methodist Society reflect on the experience.<br />

through education, we provide informed ideas and<br />

represent genuine circumstances. A very simple truth<br />

is that these refugees are humans, and vulnerable<br />

humans who need help. The choice we have is very<br />

simple: we either help them or ignore them.<br />

As a student in higher education I am fully aware<br />

of the benefits of attending university, and the<br />

influence universities have on society. The University<br />

of Edinburgh recently announced that it will be<br />

providing fully funded scholarships and a ‘significant<br />

reduction’ in costs to asylum seeking students. This is<br />

a powerful and progressive action that will hopefully<br />

influence more universities to take positive action in<br />

the current situation.<br />

Finally, I think that it is important to highlight the role<br />

that Christianity has in shaping my own views and the<br />

views of many Christians around the world. I believe<br />

Jesus is explicit in how we should treat those who need<br />

and ask for our help. ‘For I was hungry and you gave<br />

me something to eat; I was thirsty and you gave me<br />

something to drink; I was a stranger and you invited<br />

me in.’ (Matthew 25:35). Jesus didn’t exclude people<br />

from his message of hope, and neither should we.<br />

Page 8 <strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong>

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

Sarah<br />

The past decade has been described<br />

as one of the most quickly<br />

advancing of all times, and some say that no other<br />

decade in history has seen such rapid development<br />

in the fields of science, medicine and technology. It<br />

seems things are going from strength to strength,<br />

but in the excitement of learning and researching<br />

new areas, have we forgotten to look after the most<br />

important things on earth: each other?<br />

In the gospel of Matthew we see Jesus travelling to<br />

new places teaching and proclaiming his message<br />

to all people. When Jesus is told that his mother<br />

and sister are outside, he replies ‘whoever does<br />

the will of my father in heaven is my brother and<br />

sister and mother’ (Matthew 12:50). Here, it is my<br />

understanding that Jesus is making a simple but<br />

crucially important point – we are all brothers and<br />

sisters in Christ. We are all made in the image and<br />

likeness of God. We are all equal and we should be<br />

treated as such.<br />

The SCM Refugee Campaign Day began with a tour<br />

of St Chad’s Sanctuary, a place where refugees and<br />

asylum seekers can go to get food, clothes and personal<br />

welfare products. Walking through rooms filled with<br />

blankets, cleaning products and other basic living<br />

essentials we soon realised just how important it is for<br />

people to continue to donate items, how important St<br />

Chad’s and other similar projects really are, and how<br />

little the government and housing agencies are doing<br />

to help refugees and asylum seekers.<br />

We heard from Shari Brown at the charity Restore.<br />

Her talk started with a quiz, in which we learnt that in<br />

2014 there were 59.5 million refugees and internally<br />

displaced people in the world. We also learnt that<br />

less than 2% of the world’s refugee population came<br />

to Britain to seek asylum, making up only 0.23%<br />

of our population in 2013. I found these figures<br />

shocking, not only because of the enormous number<br />

of refugees, but because we could clearly see the<br />

extent to which the media exaggerates the number<br />

of asylum seekers who are really coming to Britain.<br />

Throughout the day we were extremely lucky and<br />

privileged to be joined by two people who had fled<br />

from their own countries and came to England as<br />

refugees. Listening to their stories, we learnt of the<br />

continuous struggles refugees face due to the hostile<br />

asylum system, the difficulties of leaving everything<br />

behind, including their careers and families, and how<br />

hard it is to pick up and continue life in a completely<br />

new country.<br />

Despite all of these problems and difficulties, one<br />

sentence stood out to me; a sentence repeated and<br />

emphasised by both refugees: no matter which part<br />

of England they go to, no matter what community<br />

they enter, and despite all of the negativity from<br />

the government and media, people are friendly,<br />

welcoming and willing to help.<br />

We ended the day with a theological reflection<br />

activity, and it became increasingly clear to me that<br />

people want to help, want their voices to be heard on<br />

issues such as the refugee crisis, and, despite the lack<br />

of urgency shown by the government, people want<br />

to get active in making change happen, until the day<br />

when refugees and asylum seekers are treated with<br />

the equality they want, need and deserve.<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong> Page 9

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

Peterson Toscano<br />

INTERVIEW<br />

Peterson Toscano is a theatrical performance activist using comedy and<br />

storytelling to address social justice concerns. Through his one-person<br />

comedies and lively lectures, he has delighted audiences throughout North<br />

America, Europe, and Africa as he humorously explores the serious topics of<br />

LGBTQ issues, sexism, racism, violence, gender, and climate change. He lives in<br />

Pennsylvania with his husband Glen, and blogs at www.petersontoscano.com<br />

Why do you think that the dramatic arts are<br />

a good way to pass on messages of faith and<br />

inclusion? What makes this medium effective?<br />

What is lovely about theatre and storytelling is that it helps<br />

the listener to get outside of their head. Good theatre moves<br />

the audience to feel about an issue and to not simply think<br />

about it. It can create empathy, and reveals when we are in<br />

collusion with oppressors. Also, we listen to stories with<br />

a different part of the brain, one that is not as critical and<br />

judgmental as when we listen to a lecture. We let our guard<br />

down and hear messages we often filter out or reject. In that<br />

way theatre can be a subversive art. I see the parables of<br />

Jesus working in this way, opening up the mind to a greater<br />

understanding, leading to critical thinking and deeper feeling.<br />

Many of your performances employ humour<br />

and comedy to make serious points about<br />

LGBTQ+ inclusion, gender, climate change and<br />

other issues close to your heart. How does<br />

humour help you tackle these and other issues?<br />

Humour relaxes the body and the brain. When we<br />

experience fear and shame, we physically tense up. This<br />

tension happens in the brain too – neural pathways close<br />

making it harder to reason and retrieve information.<br />

This is why when we begin to panic, it’s easy to forget<br />

simple instructions. Comedy helps to loosen us up. This<br />

is especially important when talking about hot topics like<br />

sexuality, faith, gender, climate change, and justice.<br />

You speak courageously and openly about your<br />

experiences of conversion therapy and being<br />

queer in evangelical environments. What would<br />

be the main message you would want people to<br />

take away from hearing you talk about these<br />

topics?<br />

Page 10 <strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong>

The main message I get back to over and over is that we<br />

need to be concerned about people, not politics. Much of the<br />

suffering I experienced in churches and ex-gay ministries was<br />

from people who truly believed they were doing the right<br />

thing, but they did it in an environment that insisted only<br />

heterosexual unions were blessed by God, and anything<br />

other was less than and needed to be destroyed. This in turn<br />

dehumanised lesbians and gays and bisexuals and transgender<br />

people. The political belief that it was wrong to be LGBTQ<br />

caused good people to act cruelly in the name of God.<br />

You are active in climate change activism and<br />

awareness – what role does your faith play in<br />

your work on this?<br />

I am curious about climate change as a<br />

pastoral care issue. Think of the emotional<br />

and spiritual needs of a people on a planet<br />

that is changing so rapidly. Consider the<br />

risks we face and the existential crisis of<br />

living in a world that seems ready to eject us.<br />

There are of course moral issues to consider<br />

too. I see climate change as a human rights<br />

issue that calls on people of faith respond<br />

with all the tools at our disposal.<br />

You grew up in evangelical<br />

environments and are now an<br />

active Quaker – what differences<br />

do you see between these<br />

traditions and what is the most valuable thing<br />

you can take from each?<br />

In the evangelical Church I was reminded over and over<br />

about how nothing particularly good lived inside of me. I had<br />

to be wary of the old man, my flesh, and the devil. My heart<br />

was deceitful above all things. Therefore, I needed to distrust<br />

myself and instead look outward – to God, as God was<br />

presented in the Bible as interpreted by the ministers. Perhaps<br />

because of my own insecurities and self-doubts I distrusted<br />

myself too much and trusted the ministers too much. This<br />

perspective though kept me locked up in the closet unwilling<br />

to raise any questions and terrified to come out.<br />

My experience among Quakers has been radically different,<br />

but actually not all that different from the teachings of Jesus<br />

that I overlooked for years. Quakers stress that each of us<br />

has the Light inside of us – that of God in us. Or as Jesus<br />

teaches in the Gospel, we have the Holy Spirit to guide us,<br />

the Kingdom of God inside of us. As St. Peter instructs, we<br />

have a treasure inside a clay vessel. My spiritual focus is now<br />

more inward, that the inner teacher Jesus instructs that inside<br />

us. Discernment, therefore, has become an important part of<br />

‘Gratitude happens<br />

when some kindness<br />

exceeds expectations,<br />

when it is undeserved.<br />

Gratitude is a sort of<br />

laughter of the heart<br />

that comes about<br />

after some surprising<br />

kindness’<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

my spiritual life, and fortunately I have Friends to help make<br />

sure I don’t come up with too many wacky notions.<br />

My time in the evangelical Church was not all bad. It<br />

was there I learned the Bible and studied it. While some<br />

Quakers know and read the Bible, the rich history of Biblical<br />

storytelling comes from my time in the evangelical Church.<br />

As a Quaker, you come from a rich tradition of<br />

spiritual activism and non-violence. How does<br />

this influence your work?<br />

I do comedy, and many people know comedy can be mean and<br />

mocking and dehumanising. In fact, that is the easiest type of<br />

humour and is in great demand. How better to bring low an<br />

opponent than to make fun of them. But<br />

this is not an option for me. Perhaps it is in<br />

part because of my temperament, but also<br />

because I worship in a peace church that<br />

actively seeks to be non-violent. Through<br />

the Quaker Advices and Queries, I am<br />

encouraged to see the humanity even<br />

in my opponent, which is very different<br />

than just being polite to an enemy. But<br />

this has challenged me to seek out new<br />

places for humour and storytelling.<br />

Who inspires you?<br />

My husband, Glen Retief, inspires me<br />

because of his discipline as an artist who<br />

is willing to explore trauma. He published<br />

a memoir a few years ago, The Jack Bank – A Memoir of a<br />

South African Childhood. It is about growing up white and<br />

gay during Apartheid South Africa. The book is a meditation<br />

of violence, including the extreme bullying he experienced<br />

in a government boarding school. His fearlessness to look<br />

at suffering on an individual and a national scale moved and<br />

inspired me. Now he is working on a novel about South<br />

African history. His commitment to the artistic process,<br />

the daily slog of writing along with the willingness to write<br />

whole chapters over from scratch serves as a challenging and<br />

encouraging model for me with my own art.<br />

If you could give one piece of advice to students,<br />

what would you say?<br />

Cultivate gratitude. As the New York Times Columnist David<br />

Brooks wrote: ‘Gratitude happens when some kindness exceeds<br />

expectations, when it is undeserved. Gratitude is a sort of laughter<br />

of the heart that comes about after some surprising kindness.’ 1<br />

This is just a small part of our interview with Peterson.<br />

Go online to read the whole thing, including more on<br />

comedy and climate change, and what Peterson is up to next –<br />

www.movement.org.uk/blog<br />

1 www.nytimes.com/2015/07/28/opinion/david-brooks-the-structure-of-gratitude.html<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong> Page 11

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

Beyond the Walls of the World<br />

The Theology of Fantasy<br />

Recently a friend and I were talking about how surprised we both were that fantasy<br />

literature and theology aren’t discussed together more often. While it’s true that as PhD<br />

students both specialising in theology and fantasy we’re a little bit biased, I definitely<br />

think it’s odd that whenever I try to describe my research, even to other academics, I’m<br />

often met with raised eyebrows.<br />

It’s no secret that some of the most popular fantasy texts of the past century have been<br />

written by devout Christians. The works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Madeleine L’Engle,<br />

and J.K. Rowling (to name just a few) have not only captured the imaginations of millions,<br />

but have sparked discussions on deeply spiritual themes in mainstream pop culture.<br />

While it is encouraging to hear people outside of Christian circles discuss sacrifice, belief,<br />

doubt, and radical acceptance and take these themes seriously, a question that’s not<br />

so often asked is, why fantasy? What is it about strange fairy-worlds (‘secondary worlds,’<br />

as Tolkien called them) and parallel societies that attracts authors<br />

and readers of faith?<br />

Could it be that fantasy is somehow inherently<br />

theological? Taylor Driggers<br />

Fantasy as recovery<br />

I’m fascinated by the desert fathers and mothers of early<br />

Christianity. Shortly after Constantine converted the<br />

Roman Empire to Christianity, these devotees led simple<br />

lives in monastic communities on the fringes of society as<br />

an act of protest against the new church of the empire.<br />

Every year during Lent, in reflection of Jesus’s forty days<br />

in the wilderness, the brothers and sisters would venture<br />

out into the desert alone, often experiencing mystical<br />

encounters.<br />

Even today, their reflections on these journeys read<br />

as strikingly subversive; the encounters they describe<br />

see them wrestling with more than just spiritual<br />

demons. Whenever someone comes face-to-face with<br />

a supernatural being, their entire understanding of the<br />

world, its social-spiritual order, and where they stand in it<br />

is also completely upended, turned inside-out. What was<br />

traditionally seen as dark and unclean is revealed to be a

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

trace of the divine, and what appears pure and spotless<br />

is revealed to be harmful and exclusionary.<br />

I think as readers, and especially readers of faith, our<br />

experience of fantasy literature can be very similar.<br />

Tolkien called this process – in which journeying into<br />

an alien world reveals divine, but uncomfortable truths<br />

about ourselves and the ‘reality’ we take for granted –<br />

‘recovery’: the ‘regaining of a clear view.’ His novel The<br />

Lord of the Rings dramatizes this beautifully; the simple<br />

hobbit Frodo trusts a frightening-looking stranger<br />

because, in his words, a servant of the enemy ‘would –<br />

well, seem fairer and feel fouler.’ As those familiar with<br />

the story will know, he is more than proven right.<br />

This theme of recovery crops up even in less overtly<br />

religious fantasies. Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere and<br />

Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus both revolve<br />

around underground collectives of people who have<br />

been rejected by society because of their strangeness,<br />

and in both novels, these communities offer profound<br />

challenges to the main character’s worldview. As<br />

Christians, we can understand these stories as reflections<br />

of the incarnation: divine truth revealing itself in the<br />

least likely of places. By embracing what is strange and<br />

‘other,’ fantasy reminds us that our faith is in something<br />

outside of ourselves, something that rarely fits into the<br />

safe and tidy categories we try to construct for it.<br />

Fantasy and creation<br />

Tolkien called the worlds of fantasy ‘secondary worlds’<br />

because he felt that the human artistic impulse mirrored<br />

God’s own role as creator. As inheritors of the divine<br />

image, we also must create, even though we largely have<br />

to borrow from and rearrange elements of the world we<br />

live in. Tolkien called this act ‘sub-creation,’ and it goes<br />

much deeper than just making something new out of<br />

existing elements. Instead, Tolkien saw sub-creation as<br />

a relational act, born out of a desire ‘to hold communion<br />

with other living things.’<br />

As a result, his own fantasy and many other fantasies<br />

concern themselves with the stewardship of creation.<br />

In The Lord of the Rings nature seems almost<br />

indistinguishable from myth itself; on entering the<br />

forest of Lothlórien, for example, Sam comments, ‘I feel<br />

as if I was inside a song.’ Later, the passage in which the<br />

forests of Isengard rise up against the wizard Saruman’s<br />

industrial military state has been interpreted both as an<br />

ecological parable and as a metaphor for the mythic and<br />

religious reclaiming a mechanised, violent modernity.<br />

Similar spiritual-ecological themes are found in the<br />

fantasy of Ursula K. Le Guin. The wizards in her<br />

Earthsea series have to practice humility and sensitivity<br />

in relation to their environment, carefully weighing the<br />

consequences of their actions. Her experimental novel<br />

Always Coming Home imagines a future society living<br />

simply with reverence toward the earth, allowing for<br />

greater sustainability. Just as the creation narratives in<br />

Genesis foreground the interrelatedness of creation, so<br />

the sub-creative impulse of fantasy can highlight our<br />

duty to look after creation.<br />

Fantasy, eucatastrophe, and<br />

the Christian story<br />

I want to conclude with what I think is one of the<br />

most profound parallels between fantasy literature<br />

and religious faith. Tolkien and many of his colleagues<br />

believed that at the core of any good fantasy story<br />

was the theme of radical, unlooked-for redemption,<br />

‘a sudden and miraculous grace’ that Tolkien called<br />

‘eucatastrophe.’ It was this that led C.S. Lewis to call the<br />

Christian narrative ‘myth become fact,’ and for Tolkien<br />

as well eucatastrophe suggested ‘a fleeting glimpse of<br />

[…] Joy beyond the walls of the world.’<br />

This, ultimately, is why I feel fantasy is at its core<br />

profoundly theological. In broadening and<br />

challenging our understanding of the divine, in<br />

showing us alternative ways we might live<br />

alongside creation and each other, fantasy<br />

points us towards the hope against all<br />

hope that constitutes the Christian<br />

message. By reading, creating, and<br />

experiencing mythic stories, we<br />

can learn to see our own dayto-day<br />

existence<br />

as small parts<br />

in a story that<br />

God is telling –<br />

one that is far<br />

from over.

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

Hagiography Orthodox Icon Painting<br />

The art of religious icons in the Orthodox Church is called<br />

hagiography as it depicts saints and religious scenes.<br />

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the religious icon<br />

paintings of Byzantium were considered primitive and<br />

unrefined compared to western Renaissance painting.<br />

It is only in the last few decades that art historians<br />

are realising the true worth of icons and the thinking<br />

behind them. The saying, ‘a picture paints a thousand<br />

words’ directly applies to hagiography. From the early<br />

days of Byzantium, icons have played an important role<br />

in church life. The wall paintings in an orthodox church<br />

are not purely decorative – they are there to assist the<br />

faithful to leap up from the mortal world to the kingdom<br />

of God during the holy liturgy. Many churches and<br />

chapels built during the height of the Byzantine Empire<br />

are still in use today. If you were to walk into one of<br />

these temples you would find a sea of colour and gold<br />

on every surface. You would be surrounded by a heavy<br />

aroma of incense and the glow of candle light reflecting<br />

off the golden halos and decorations that cover the<br />

walls. The impressive wealth of art from floor to ceiling<br />

cannot possibly go unnoticed.<br />

In the Western church, the depictions of biblical scenes<br />

became naturalistic, realistic and contemporary. In the<br />

traditions of orthodox icon painting, things are quite<br />

different. The style of icons and the depictions of holy<br />

persons follows a strict set of rules and guidelines that<br />

have been in existence for almost two thousand years.<br />

Byzantine art has a spiritual element to it. The icon<br />

painter strips away the human elements of the person<br />

being depicted, presenting him or her as an unblemished<br />

role model with pure spirit. According to the great 20th<br />

century icon painter Fotis Kontoglou, Byzantine icon<br />

painting ‘isn’t naturalistic, because its purpose isn’t just<br />

to portray the natural, but also the supernatural’. Apart<br />

from the minor changes in equipment, the techniques of<br />

Byzantine icon painting have gone unchanged.<br />

In today’s hectic world, hagiography still offers a<br />

taste of a nostalgic lifestyle. When I began studying<br />

as an apprentice to a Greek icon painter, I started to<br />

understand what icons actually mean, and the amount<br />

of love and effort that goes into creating them. Icon<br />

painters won’t sit in front of a canvas and wait for<br />

inspiration to create something. Traditionally they fast,<br />

Page 14 <strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong>

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

pray, and embark on the spiritual journey of creating an<br />

icon. In the early days of icon painting, the works would<br />

go unsigned as a mark of respect to God. In the last few<br />

centuries the painter will sign the painting with ‘hand of’,<br />

and their name and year. This is done to show that God<br />

guides the hagiographer’s hand to create the icon just<br />

as he guided the evangelist Luke, the first icon painter.<br />

The process on which the painter embarks is just as<br />

unique as the materials used. The materials used in<br />

hagiography are the catalysts which enable the painting<br />

to reach a divine quality; they come from nature and<br />

have to be prepared with respect and care. The most<br />

natural material used is wood. Wood tends to warp<br />

and flex over time, therefore the application of gesso,<br />

which is a combination of white chalk and hide glue, is<br />

necessary before painting. This creates a buffer between<br />

the wood and the pigments in the paint. If paint was<br />

applied straight onto the wood, a few hundred years<br />

later the paint would probably have cracked under the<br />

stress of the warping. From a symbolic and theological<br />

perspective, the colour of gesso enhances the divinity<br />

of icons, as white is the colour of purity. By adding gold,<br />

the painting takes on a spiritual quality that allows the<br />

viewer to get closer to heaven.<br />

Once the wooden panel is prepared the design gets<br />

drawn out, traditionally in charcoal. If the hagiographer<br />

were painting onto a wall, they would trace the design<br />

onto a specially prepared piece of cloth called an<br />

‘anthivolo’, and use this to transfer the design. This<br />

would have been done by using a technique called<br />

pouncing, which involved using a sharp tool to make<br />

a series of tiny holes along the outline of the drawing.<br />

Wall paintings are done in fresco technique, which<br />

involves painting quickly directly onto wet plaster, as<br />

the painting must be finished before the plaster is dry.<br />

With the design laid out, the icon is then gilded using<br />

a process called water gilding. Traditionally, the painter<br />

would take red clay from Armenia and mix it with water<br />

and hide glue before applying it to the icon in layers. The<br />

gold would then be applied to the surface with alcohol.<br />

When dry, the gold is burnished with a tool made of<br />

agate. Although this method is very costly and laborious,<br />

it gives the icon a beautiful shine and ensures the gold<br />

is resilient to scrapes and surface damage. Nowadays,<br />

the method for gilding is much simpler. A varnish is<br />

coated onto the gesso and then a glue, known as size, is<br />

laid onto the surface and allowed to activate. After the<br />

gold is applied the surface is dusted and varnished. This<br />

method is known as oil gilding.<br />

Once the gold has been laid out, the hagiographer<br />

prepares to paint by preparing the medium. According<br />

to the Byzantine traditions, the pigments in the paint<br />

were bound with a mixture of egg yolk and vinegar. This<br />

type of paint is known as ‘egg tempera’ and is a very<br />

strong medium that doesn’t discolour over time and<br />

after a few years becomes water resistant. However,<br />

this means that it cannot be used on a flexible surface,<br />

and it is attractive to flies! Egg tempera is relatively easy<br />

to make as the ingredients can be taken from nature<br />

with little refinement required. It dries quickly, which<br />

means that the painter doesn’t have enough time to<br />

make the image too sensual.<br />

Due to this process, Icon painting has survived hundreds<br />

of years. The fact that some of the techniques used by<br />

icon painters today are older than the Roman Empire<br />

itself is mind blowing. John of Damascus claimed that,<br />

‘an icon looks like the original, but it is also different<br />

from it’. The divine is invisible, but the human idea of<br />

divine can be visible and tangible, which is why icons are<br />

still created today. The beauty of an icon is more than<br />

just the painting itself, rather it is the combination of<br />

techniques, effort and a way of thought that has lasted<br />

for centuries. Byzantine icon painting harnesses art<br />

and fuses it with faith. This beautiful combination has<br />

survived for hundreds of years, and will continue to be<br />

practiced as long as there is someone to appreciate it.<br />

MICHAEL DIMITRIS LEKAKIS IS A HAGIOGRAPHER<br />

BASED IN GLASGOW.<br />

Images © Michael Dimitris Lekakis.<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong> Page 15

The Bard<br />

& the Bible

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

SCM member Ellie Wilde explores what we can gain from reading the<br />

bible in the way that we read the works of Shakespeare.<br />

A<br />

s an English Literature graduate, I have always<br />

read the Bible and Shakespeare’s works in a<br />

similar way. My degree has taught me to look<br />

deeper at written texts; peeling away the layers behind<br />

the printed words comes naturally. At the simplest level,<br />

the Bible and Shakespeare are both written texts: or more<br />

accurately, collections of works, which come together as<br />

one exceptional whole. Both have shaped and enriched<br />

the English language and culture and both are national<br />

treasures of our country. As Robert McCrum observed<br />

in The Guardian: ‘Shakespeare and the Good Book have<br />

been informally linked as supreme expressions of the<br />

English language.’1 Any level of analysis, especially with<br />

words this precious, must be faithful to the spirit of the<br />

text. This includes the intentions of the author and the<br />

context in which it was written. So, how can we read the<br />

Bible and Shakespeare’s works in the same way? How can<br />

we search for the essential meaning behind these words,<br />

after so many years?<br />

Shakespeare’s England would seem a strange country to<br />

us. Not just the sights, sounds and smells of 16th century<br />

London, but the way the people understood the nature<br />

of life itself. Kings were divinely appointed, and man sat<br />

between angel and animal in a strict hierarchy. Reading<br />

was a privilege of the rich, and Shakespeare was very lucky<br />

to have the right social status to be taught how to read and<br />

write. The ordinary Elizabethan received their education,<br />

moral instruction and entertainment through stories,<br />

songs, plays and sermons. They were highly attuned to the<br />

sound, shape and rhythm of words. This is why much of<br />

Shakespeare’s genius is lost in translation. We read from a<br />

page rather than speaking on a stage. We don’t pronounce<br />

words the same way, or know the same in-jokes and<br />

cultural references that he grew up with.<br />

So, if we are to read the Bible in the same way, what we<br />

must really try to do is hear it. Certain parts of the Bible<br />

are meant to be read out loud, or set to music. The Psalms<br />

are one obvious example – there are even instructions for<br />

which instrument to use included in the text. The Song<br />

of Solomon compares to some of Shakespeare’s most<br />

beautiful sonnets, and even perhaps inspired them. There<br />

is a theory that Genesis was originally a Hebrew poem.<br />

When translated we lose the rhythm of the words – and<br />

perhaps, some of the meaning. Indeed, the Torah is sung in<br />

the Jewish tradition, using special melodies to accentuate<br />

the original sense of the words. Jesus used stories and<br />

speeches regularly in his ministry, often ‘performing’<br />

before a crowd, trying to communicate religious and<br />

moral truths. Many stories in the Bible can be seen as<br />

allegories or myths, and many arose from an oral history.<br />

Some stories would have gone through countless retellings<br />

before being written down; they were told in community<br />

and committed to memory.<br />

Each actor in an Elizabethan play only had their own<br />

part of the script: it told them their cue to speak, their<br />

lines, and nothing else. In the same way, the writers of<br />

the Biblical texts couldn’t possibly have seen or predicted<br />

their part in the whole text we now call the Bible. They<br />

couldn’t have imagined the impact their words would have<br />

on generations of believers. Paul was writing to specific<br />

churches; David wrote prayers and songs for worship; the<br />

Gospels document one remarkable man’s life. Keeping<br />

this in mind, it becomes almost impossible to read the<br />

Bible as one consistent whole. Many Christians believe<br />

that, like Shakespeare’s plays, there was a guiding hand<br />

bringing all these separate parts together – that God in<br />

some way orchestrated the Bible as a whole. Even if we<br />

believe this to be true, we must also recognise that each<br />

book of the Bible came from a different context.<br />

There have been years of speculation over the identity<br />

of Shakespeare. We’ve formed theories about his social<br />

status, his literacy and even his sexuality. Much has also<br />

been speculated about the character of God. Reading the<br />

Bible, we could be said to be searching for the identity of<br />

God, the ultimate inspiration. As a whole, the Bible shows<br />

us overarching themes and clues, a breadcrumb trail to<br />

follow. To follow this trail, we should first acknowledge<br />

that we only have one tiny piece of the puzzle. We live in<br />

the modern world, with its own moral code, structures and<br />

cultures. We bring this with us to any text, seeing through<br />

the filter of our own worldview. Just as we will never truly<br />

understand Shakespeare’s worldview, we are far removed<br />

from the Biblical writers’ daily lives.<br />

To really connect with the spirit of Shakespeare’s works,<br />

English Literature students are encouraged to go back in<br />

time, to study the context in which Shakespeare wrote.<br />

They read aloud, listen, perform and engage with the<br />

texts in an authentic a way as possible. Only then can<br />

they truly grasp his meaning and intentions. If we are to<br />

find the spirit of the Biblical texts, to truly connect with<br />

their message for us as Christians, perhaps we should do<br />

the same thing. Perhaps we can go back in time, to the<br />

original language and context – and discover a whole new<br />

dimension to the Bible we know and love.<br />

1. Robert McCrum,‘What I learned from the word of the Bard, by Rowan Williams’ 28th Dec 2014, The Observer: bit.ly/shakespeare-bible<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong> Page 17

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

Three perspectives on…<br />

Music in Worship<br />

PENTECOSTAL<br />

I hail from the southern state of Tennessee in the United States of America. I grew up as an active member in the Church<br />

of God in Christ, a Pentecostal denomination started in 1907. Today, the Church of God in Christ is the United States’<br />

largest predominately African American denomination. I come from a long line of Church of God in Christ pastors,<br />

preachers, and missionaries — five generations, in fact. As a child I would help lead the Friday night worship service in<br />

my great uncle’s church, beating a tambourine and singing off-key.<br />

In true ‘black church’ tradition, the music played during our worship services utilises gospel and congregational<br />

hymns. A choir is a main feature of the worship service and leads the church into an atmosphere of praise. Expressive<br />

demonstrations of emotion are welcomed and encouraged, and you will likely see church attendees raise their hands<br />

in the air, clap, and sing loudly. The music is meant to be inspiring and uplifting, offering a promise of eternal hope to<br />

those who trust in God to deliver them from their earthly troubles. In reflecting upon the history of African-Americans<br />

in the United States, the encouraging themes found in the music of the black church are both intentional and purposeful.<br />

African-Americans have endured slavery and the Jim Crow era; the fight for equality continued through the Civil Rights<br />

QUAKER<br />

After pacifism and the man on the Quaker Oats packet, the next most common association with the Religious Society of<br />

Friends is probably that we worship in silence. If you visit a Quaker Meeting House in Britain you won’t find hymn books<br />

readily available. What is music’s place in a tradition where silence is a core component of worship?<br />

From the beginnings of the Quaker movement in 17th century England, music was viewed with suspicion. Instrumental<br />

music was avoided, as time spent striving for excellence on a musical instrument could be better spent on something<br />

else. Solomon Eccles, a music teacher when he became a Quaker in the 1660s, burned and crushed his violins with an<br />

incredulous crowd looking on because he saw ‘a difference between the harps of God and the harps of men’. George<br />

Fox, an early Quaker leader, wrote that music ‘burdened the pure life, and stirred people’s minds to vanity.’ Singing was<br />

more acceptable, as long as songs arousing inappropriate emotions were avoided. Singing had a place within Quaker<br />

worship, but only when prompted by the Holy Spirit and never from a book.<br />

Attitudes in Britain softened in the 20th century, with the formation of the Quaker performing arts group ‘The Leaveners’<br />

in the 1970s, and music is no longer seen as a vain distraction. Music and song will often be found at Quaker gatherings<br />

CATHOLIC<br />

To me, the Catholic Church is unique in that no matter which church you go to, in any city or in any country, every<br />

Catholic mass that is said on that day will have exactly the same structure; the same readings, creeds, prayers and<br />

actions in exactly the same part of the mass. The only thing that differs is the music, the hymns and songs that are used<br />

and whether certain prayers are said or sung.<br />

I think this is why music has such an important role in my Christian identity. Music is the one thing that gives each church<br />

its uniqueness, and is the one thing that all denominations seem to have in common.<br />

When I tell people I’m Catholic, the first thing they usually ask is if the services are as long, boring and structured as<br />

they’re said to be. And although the Catholic Church is known for keeping its structure and tradition, to me, mass doesn’t<br />

feel like this at all – it’s a place of love, joy and freedom.<br />

Page 18 <strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong>

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> of the 1960s and in many ways, the fight continues today. Throughout this history,<br />

the church has played a monumental role in the lives of African-Americans, providing<br />

refuge and sanctuary from the cruel injustices of the outside world. It was during the Sunday<br />

morning church service that African-Americans received a re-filling of faith and motivation<br />

to endure the week ahead. All parts of the service were directed towards this goal, from the<br />

uplifting praise songs to the fiery, passionate words of the sermon. With this understanding<br />

of the church’s connection to activism, it is undoubtedly fitting that Dr. Martin Luther King<br />

Jr. delivered his final sermon, ‘I’ve Been to the Mountaintop’ at Mason Temple, the Church<br />

of God in Christ church headquarters in Memphis, Tennessee, the day before he was<br />

assassinated. In acknowledging the historical significance of the black church and specifically<br />

the Church of God in Christ, I remain proud that the music powerfully sung every Sunday<br />

embodies the spirit of resilience, hope, and a commitment to justice. FEYLYN LEWIS<br />

and several Quaker songbooks have been published. The suspicion of ‘prepared ministry’<br />

(planning what you’re going to say in worship beforehand) persists. In my experience, sung<br />

‘ministry’ in worship is rare, and is always spontaneous and from memory. The worldwide<br />

picture is somewhat different, with ‘Programmed’ and ‘Evangelical’ Quakers (who form the<br />

majority of Quakers in the world) having a rich tradition of hymn singing.<br />

I would love to see British Quakers embrace music more readily in our worship, and that<br />

means finding more opportunities to sing together. Simple, repetitive chants (such as those<br />

from Taizé), beginning or ending as the Spirit moves, fit well with Quaker practice. As in<br />

jazz improvisation, we can only play around with material we already know. The richer our<br />

musical vocabulary, the more readily we’ll be able to use song to express the workings of the<br />

Spirit in our worship. To quote a song much loved by Quakers, ‘since love is Lord of heav’n and<br />

earth, how can I keep from singing?’ MARK RUSS<br />

For me, singing is an expression of joy. In my local church, mass seems to be incorporated<br />

around the singing rather than singing being incorporated into the mass. With singing at least<br />

three hymns and most of the prayers, and having a church choir, I can definitely say it’s music<br />

that brings my church together in unity.<br />

Whenever I come out of any kind of worship where there has been a lot of music or singing,<br />

I’m always reminded of the time when, walking out of Church in Taizé, France, one of the<br />

visiting nuns whispered in my ear ‘those who sing pray twice’. I later found out that this was<br />

an ancient proverb, and I think it sums up perfectly just how important and special music in<br />

the church really is. SARAH DERBYSHIRE<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong> Page 19

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

Faith and Art<br />

The secular is seen as lesser in value and not as worthy of our<br />

There is a tendency amongst<br />

Christians to separate life – our<br />

work, our hobbies, our relationships<br />

– into that of either secular or sacred.<br />

in the home, doing their jobs well to the best of their ability and<br />

attention or energy, whilst the sacred is set above everything demonstrating the love of God to those they are in contact with<br />

else and elevated to a position of importance. This mind-set is on a day-to-day basis.<br />

no less prominent in the Arts, with many Christians believing<br />

My faith informs my art as much as it informs every other<br />

that unless the subject matter is overtly Christian, the object<br />

aspect of my life and it is important for me to actively remember<br />

or work is of inherently less value or even in some cases<br />

this as I create – to invite God in to what I am making and ask<br />

potentially dangerous as it reflects ‘worldly’ values or beliefs.<br />

Him to inspire me, encourage me, and lead me in the right<br />

As both a Christian and a self-employed Fine Artist I find this<br />

direction. I strive to use the gifts that I believe God has given<br />

way of thinking extremely unhelpful. I don’t view my career as<br />

me in order to create ‘Good Art’ that will fulfil the calling I<br />

an artist as something fundamentally separate from my faith;<br />

have been given, serve and love others well, and, first and<br />

rather I see the two as intrinsically connected. I believe that<br />

foremost bring glory to the original Creator. Francis Schaeffer<br />

the gospel permeates every aspect of my life as a Christian,<br />

put it best when he said, ‘A Christian should use these arts<br />

and what I do in the studio is just as important to God as what<br />

to the glory of God—not just as tracts, but as things of beauty<br />

I do in a Church meeting on a Sunday; He is as much involved<br />

to the praise of God’. Whether indirectly or otherwise, I hope<br />

in my painting process as my Bible reading. I believe that it is<br />

that to some degree my paintings invite people in to consider<br />

hugely important to have Christians working out their faith in<br />

both creation and its Creator more deeply. I want my paintings<br />

all areas of life, be that in cafés or in parliament, in schools or<br />

to communicate something of the truth of God, and the true<br />

hope, joy, and freedom that can be found in Christ.<br />

We have been made in God’s image, and thus we are inherently<br />

creative beings (though this may be truer of some than others!)<br />

Through the act of painting I am mirroring on a small scale<br />

what God initiated at the very beginning of time. I paint as an<br />

overflow of God’s creative Spirit within me, and in response to<br />

the world around me which is full to the brim with inspiration.<br />

Having studied and lived in Cornwall for the last five years my<br />

art, and indeed my faith, have been inspired by the stunning<br />

coastlines and vistas of this beautiful county with its unique<br />

and enchanting light. I hope that my work demonstrates<br />

something of the beauty of the world we live in, and the joy<br />

that can be found therein.<br />

As a Christian I also recognise God’s presence and hand at<br />

work throughout all of life, and as such the work I produce<br />

is born out of this conviction. Artists often create work that<br />

is an expression of the deepest part of themselves – for me<br />

this deepest part is my identity as a Christian and so in some<br />

ways, regardless of the subject matter of my paintings or the<br />

message I may want to communicate, the work is emerging<br />

out of this renewed life and personhood that I have in Christ,<br />

making it inherently Christian in what I believe to be the truest<br />

sense of the word.<br />

Ruth Naylor is a self-employed Fine Artist and, as of February 2016, a part-time Administration Assistant at SCM.<br />

She studied Fine Art at Falmouth University in Cornwall and now lives and works in Birmingham. You can find her<br />

work at ruthnaylor.co.uk<br />

Page 20 <strong>Movement</strong> – Issue <strong>153</strong>

groovement<br />

Across<br />

6. Back for improvement - same again (7)<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> summer 2016<br />

7. This conducts a stream away (7)<br />

9,15. Somehow, amazingly arty tiger gets 7 of 12 10 (5,9-4)<br />

10. Plan on losing first of two earrings with band (9)<br />

11 . Weirdly bloated, I replaced energy with something<br />

like an iPad (7)<br />

13 . See 24<br />

15 . See 9<br />

19 . Fresh secondary burns (6)<br />

20 . Permitted marshmallow edible in part (7)<br />

23 . A great egg scrambled whole (9)<br />

24,13. Dubious tonal merits of 9, 15’s predecessor (5,6)<br />

26 . Zero tax on charged particle gets a rousing reception (7)<br />

27 . Keys that jingle when 11 overs bowled (7)<br />

Down<br />

1. Beats up in fight (4)<br />

2. Japanese Emperor crazy about Indian King Oscar (6)<br />

3. Taping band around electric cable (9)<br />

4. Our elephant sounds apposite (8)<br />

5. Reservists show disappointment in Wales reversing<br />

acts of parliament (7,3)<br />

6. Distant return section of route to merge (6)<br />

7. False ridicule (4)<br />

8. Arouse knowledge under central section of seawall (6)<br />

12 . Bring ham, I’m cooking in the city (10)<br />

14 . Tactical tiger acts strangely (9)<br />

16 . An old blimp follows musical LED (8)<br />

17 . Zero tax rises in business - you could write a book,<br />

this size, on it! (6)<br />

18 . Youthful beauty makes fuss over flipping<br />

transgression (6)<br />

21 . Reading class (6)<br />

22 . Deserve to hear noisy extract (4)<br />

25 . Principal aroma ingeniously concealed (4)<br />

Crossword problems?<br />

Don’t know where to start? Try<br />

solving-cryptics.com or the<br />

Guardian ‘Cryptic crosswords<br />

for beginners’ blog.<br />

This CartoonChurch.com cartoon by<br />

Dave Walker originally appeared in the<br />

Church Times.

<strong>Movement</strong> Issue <strong>153</strong> spring 2016<br />

acts of the imagination<br />

Great deals<br />

for 18– 25s<br />

Details online<br />

Music NaHKo & MediciNe for tHe PeoPle kitty, daisy & lewis Hot 8 Brass BaNd<br />