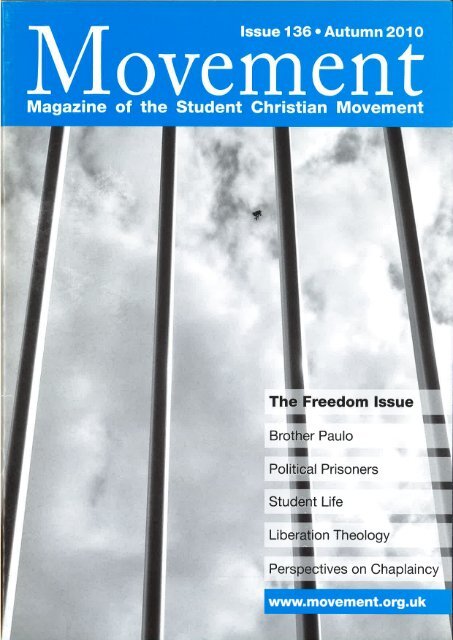

Movement 136

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

-** r [:<br />

fJ<br />

r].<br />

j<br />

H -#<br />

F *<br />

l<br />

e t €<br />

F<br />

The Freedom lssue<br />

i.I<br />

Brother Paulo<br />

il<br />

Political Prisoners<br />

,il<br />

Student<br />

n<br />

Life<br />

Liberation Theology<br />

::<br />

Pe<br />

il<br />

n<br />

T<br />

ives on Chaplaincy<br />

wvvw'movement.org,uk

o<br />

sddenr<br />

Christian<br />

<strong>Movement</strong><br />

SGM is a movement seeking<br />

to bring together students of all<br />

denominations to explore the<br />

Christian faith in an open-minded<br />

and non-judgemental environment.<br />

Editorial and Design: Thontas Worrall<br />

Proofreading: SCM Staff<br />

Gover photo; O H. Assaf<br />

SCM staffr National Co-ordinator<br />

Hilary Topp; Links Worker,9osre Venner;<br />

Administrator Matt Gardner<br />

SCM office; 30BF The Big Peg,<br />

120 Vyse Street, The Jewellery<br />

Quafter, Birmingham 81B 6ND<br />

. O'121 200 3355<br />

. scm@movement.org.uk<br />

. wwur.movement,org.uk<br />

Printed by: Henry Ling Limited, Dorchester<br />

lndividual membership of SCM (including<br />

<strong>Movement</strong>) costs t15 per year.<br />

Disclaimer: The views expressed in<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> are those of the pafticular authors<br />

and should tlot be taken to be the policy<br />

of the Student Christian <strong>Movement</strong>.<br />

<strong>Movement</strong> is a member of lNK, the<br />

lndependent News Collective, trade assoctation<br />

of the UK alternative press. ink.uk'com<br />

tssN 0306-980x<br />

Charity number 1 125640<br />

@ 2010 scM<br />

Do you have problems<br />

reading <strong>Movement</strong>?<br />

lf you find it hard to read the printed version<br />

o/ <strong>Movement</strong>, we can send it to you in digital<br />

fo r m. Co ntact edito r@ move m e nt.o rg. u k.<br />

-Na\e lrontiers shift like dese,'1 sa/ics<br />

\i/hile natians i,asn lhetr blaadied hands<br />

Ol la1,db. cf t rtc1,. .F

The Freedom lssue<br />

"ltts a free country."<br />

Think back to when you were a child. What were your dreams for<br />

the future? Perhaps you flitted between wanting to be an astronaut<br />

or a fireman as the whim took you. Or perhaps you had a more<br />

strongly held ambition that you clung to throughout the years.<br />

The message I rememberfrom my early childhood was one of hope<br />

and opportunity. The Berlin Wall came down. Thatcher resigned as<br />

Prime Minister. My working class parents went back to university<br />

to train as a teacher and a furniture restorer. ln my early teens, the<br />

dot-com bubble showed that any penniless whizz-kid with a good<br />

idea could make millions. The youth of Britain were truly free to do<br />

and be anything they set their minds to.<br />

To an extent, that was true. I was able to attend a university of<br />

my choice, to study anything I wanted. While there are differences<br />

from how, as a child, I anticipated my life at age 25, on the whole<br />

l've been able to make my own choices.<br />

lntrod uction<br />

Spare a thought for those without this luxury. As a child I had to<br />

eat my greens because of those poor starving children in Ethiopia.<br />

F' t<br />

.,t<br />

There have always been war-torn or povedy-ridden corners of the<br />

globe. Think of the children in this country who have been conditioned<br />

from an early age that learning is for wimps, or those who<br />

jump straight into a low-paying and boring job because their family<br />

needs the extra wage. The freedom I have always enjoyed comes<br />

with a small measure of guilt attached. But like many of my generation,<br />

I put it aside to face the difficult decisions my life requires:<br />

,<br />

what brand of shampoo to buy, or whether to go out for a few pints<br />

when I have a deadline tomorrow...<br />

Tom<br />

The future of <strong>Movement</strong><br />

<strong>Movement</strong> magazine is currently undergoing a big change. We are<br />

reviewing what goes inlo <strong>Movement</strong> and how it can best reflect<br />

the movement as a whole. Whilst we are doing this review we<br />

are going to produce one more magazine of this current format<br />

before a big change for the summer issue. One big thing that has<br />

already come out of this review is that we want our readers to get<br />

more involved. You can do this by writing for Movemenf, sending<br />

in photos or art, or by joining the editorial group that actually decides<br />

what goes into <strong>Movement</strong>. To get involved with any of these<br />

things or just to tell us what you think about <strong>Movement</strong> email<br />

publications@movement.org.uk, or visit SCM's website at<br />

movement,org.uk and chat with us on the blog or the forums.<br />

Autumn 2010 n <strong>Movement</strong> . 3

News<br />

Gelebrating the SCM community<br />

Heslington Church in York hosted this year's<br />

SCM AGM and summer gathering over the<br />

weekend of 4-6 June. SCM members came<br />

from all over the country to take pad in workshops,<br />

worship, bible study and discussions<br />

with the theme of Celebration at the heart<br />

-<br />

of the event, We were joined by speaker Theo<br />

Hobson, who stimulated much debate around<br />

the use of ritual and celebration in the church.<br />

A new General Council (GC)was elected; you<br />

can find out more about the new GC members<br />

in the autumn issue of Grassroofs or on the<br />

SCM website.<br />

Hello to Lisa, our new Administrator<br />

We welcome Lisa Murphy to the SCM office team as our new Administrator. She has a background in youth<br />

work and administration. Lisa has also been a chaplaincy assistant and a member of the Catholic Student Forum<br />

steering group, Lisa started working for SCM at the end of August, so we asked her to introduce herself:<br />

Where do you call home?<br />

l'm from Stoke on Trent originally, and even<br />

though I haven't lived there for four years now<br />

it's still where my heart is, Mainly because<br />

people there pronounce 'book' 'look' and<br />

'cook' the same as I do!<br />

What is your favourite film?<br />

I have too many favourites to choose from! lf<br />

I could only watch one more film ever though<br />

it'd probably be The Lord of the Rings.<br />

What are you reading at the moment?<br />

Probably emails!<br />

What is your favourite word?<br />

Chocolate. Especially in a sentence with 'do'<br />

'you''want' and'some'.<br />

What are you looking forward to most about<br />

working for SCM?<br />

Getting stuck in and meeting new people!<br />

4 . <strong>Movement</strong>. Autumn 2010

I<br />

Interview<br />

utith Taiz6's<br />

Brother Paolo<br />

f<br />

'nrtF<br />

.11<br />

i<br />

,,,,1,<br />

e<br />

I<br />

Many readers of this magazine will know of the Taizd Community, an ectlmenical monastic<br />

community which grew from the arrival of its founder, Brother Roger, in the French village<br />

of Taizd duringWorldWar Il. Since the 1-960s, whenlarge numbers of young adults started<br />

to visit, the community has developed a particular ministry of welcoming young people to<br />

share its life of prayer, work and fellowship. In October, SCM and Taizd will be hosting a<br />

weekend for students in Manchester (see back cover of Movem ent for more information).<br />

Brother Paolo, who will be part of that, kindly agreed to be interviewed for <strong>Movement</strong>.<br />

Where are you from originally, and what did<br />

you do before coming toTaiz6?<br />

I was born in Gloucester.In1,972, when I was 16,<br />

I came toTaiz6 for a week with a group organised<br />

by an Anglican youth chaplain. The experience<br />

there and the thinking which was started within<br />

me led to all sorts of things: getting involved in<br />

several volunteer projects in Britain, and joining<br />

SCM when I got to university!<br />

How did you discern the call to become a<br />

brother atTaiz6?<br />

Through a nagging sense, on the one hand, that I<br />

needed to discover a basis for my life, not just to<br />

do interesting and good things. And on the other<br />

hand, the discovery that prayer could be a kind<br />

of "letting go" of my own ideas and projects in<br />

order to see more clearly what was right for me<br />

and what was my deepest desire.<br />

How did your farnily and friends react to<br />

your decision?<br />

For quite a while after arrivingatTaiz6 to stay, I<br />

kept a low profile! I needed to mark a new beginning.<br />

When I had been atTaizl quite a while, over<br />

two years I think, my father came to stay - just for<br />

a few days. He had not been to church for about<br />

25 years. He was timid at first, but very quickly<br />

Autumn 2010 " <strong>Movement</strong> . 5

lnterview<br />

It's when people<br />

are free enough<br />

to be able to ask<br />

questions that<br />

good changes<br />

he was fascinated and began to feel at home. A<br />

few months after, I phoned hom a Sunday,<br />

because you phoned at weekends in those days,<br />

when it was cheaper and they were out. Later<br />

-<br />

on in the day, they were in, and he explained<br />

that they "must have been at church" when I<br />

first called. Somehow, his short stay here had<br />

removed little barriers which had been erected in<br />

his life, and given him more space and freedom.<br />

What might a typical day at Taizd involve<br />

for you?<br />

Well, we are together in the church f.or prayer<br />

three times a day: B:15am, 12:20pm, B:30pm.<br />

And most of the brothers of the community eat<br />

lunch together in silence with music. Some<br />

-<br />

days I work in the pottery, but not doing anything<br />

artistic, just preparing the clay for use! The<br />

community earns its own living aside from what<br />

visitors contribute for their<br />

COme.<br />

stay (which covers just the<br />

cost of the youth meetings),<br />

and the pottery we make and<br />

sell is our main work. Very<br />

often during the day I meet<br />

with a group, a bible-study<br />

group, or a work group, or a<br />

group visiting from Britain.<br />

Then, back in my room, where<br />

there is both a bed and a table with an internet<br />

connection, I may do some work on the community<br />

website which I program. After the evening<br />

prayff there is an open space: there is nothing<br />

more on the timetable, and the singing continues<br />

in a kind of vigil for those who discover, at<br />

the end of the more formal part of the prayer,<br />

that they want to remain and pray. Some of us<br />

stay in the church in the evening for those who<br />

want to speak about something personal.<br />

Why do you think so many young people are<br />

drawn to visit Taiz6?<br />

Although many young people come in groups<br />

especially the first time they visit, the majority<br />

are somehow conscious that they are coming on<br />

a personal journey of discovery: somehow this<br />

stay will be connected with important things,<br />

with the meaning of their life. When speaking<br />

with young people who are already here, they appreciate<br />

the freedom they have to be themselves,<br />

to talk with anybody, to approach people from<br />

different countries and backgrounds. Why the<br />

connection with the young? I don't know for sure,<br />

but I have an inkling that it is connected with a<br />

"search for meaning". Such a search is strong for<br />

young people who are beginning to take on more<br />

complete responsibility for their own lives. And a<br />

monastic commitment, if it is lived authentically,<br />

also places us in a situation where, because of a<br />

radical choice not to possess, we have to search<br />

for meaning over and over again.<br />

What do you think are the most important<br />

questions for young people today to be considering?<br />

I don't know. The important thing is, I believe,<br />

for young people to be able to look on the world<br />

and on their own experience, and dare to ask<br />

fundamental questions. It's when people are<br />

free enough to be able to ask questions not only<br />

in words, but to take the first steps by the way<br />

they live, without imposing them on anyone else,<br />

that good changes come. That freedom though,<br />

which is above all an inner freedom, needs to be<br />

anchored in a sense of belonging. And, for many,<br />

searching for that is one of the main questions.<br />

Where do you think the future of ecumenism<br />

lies?<br />

There is only one God and one Christ. So the<br />

unity that we seek is not anything we build, but<br />

rather discovering the unity which already exists<br />

in God. If we seek to discern Christ in others,<br />

we shall be led together. Ecumenism - seeking<br />

visible unity - also implies a trust in the Church<br />

which is unfashionable. Timothy Radcliffe has<br />

sometimes said that we live in an age of suspicion<br />

and that we also need to learn to "suspect<br />

the good". I think of the European Meetings<br />

which our community organises annually for<br />

f<br />

6. <strong>Movement</strong> . Autumn 2010

lnterview<br />

young adults as an exercise in<br />

this. In the autumn we set out<br />

to discover the hidden treasure<br />

of the Church in some large<br />

city (this year it is the turn of<br />

Rotterdam). And each year, for<br />

over 30 years now, thousands<br />

of families offer free accommodation<br />

to tens of thousands<br />

of young people for 5 nights.<br />

I ask myself: What other human<br />

organisation, apart from<br />

the Church, could provide the<br />

focus for such an expression of<br />

generosity?<br />

What advice would you give about living in<br />

community?<br />

Community is a word which is used in many ways.<br />

My own experience is that of a lifelong monastic<br />

community. Because of the lifelong commitment,<br />

there is plenty of time, we can be patient as we<br />

grow in understanding both of ourselves and of<br />

others. Three times a day we gather for community<br />

prayer and I think of two things which<br />

quite frequently happen in my own prayer which<br />

directly affect the way I relate to the others. First<br />

there is the astonishment at the beauty of life<br />

which can break out within. When that happens,<br />

differences and misunderstandings with others<br />

are swept awayby something large and deep. It is<br />

as Peter writes, "love covers a multitude of sins"<br />

(1 Peter 4:B). And the second experience is the<br />

consciousness of my own weakness and emptiness.<br />

And that realisation burns - burns away,<br />

gradually, a judgmental attitude towards others.<br />

It is not a pious platitude to say that our life at<br />

T aiz6. t ev olves around prayer: our community life<br />

could not be anything like it is without it.<br />

What is the place of freedom in vowed religious<br />

life?<br />

Women and men the world over continue to live<br />

a vowed religious life with great freedom. If you<br />

don't know this, it is probably worth going to<br />

visit a religious community near you. You may<br />

get a glimpse of a life, and a freedom, which you<br />

did not suspect. Brother Roger, who settled in<br />

Taiz6 in 1940, had an undoubted gift for fostering<br />

a close-knit community in which, nevertheless,<br />

each community member has the freedom<br />

to be who they are. In the "Rule of Taiz6", which<br />

he wrote in 1958, as well as in our community<br />

life today, there are no superfluous rules to force<br />

a kind of external unity. Brother Roger was<br />

clearly conscious of the necessity for the freedom<br />

of personal integrity when he wrote in the<br />

short introduction: "This Rule contains only the<br />

minimum necessary for a community seeking to<br />

build itself in Christ, and to give itself up to common<br />

service of God. This resolve to lay down only<br />

the essential disciplines involves a risk: that your<br />

liberty may become a pretext for living according<br />

to your own impulses." Without that freedom<br />

though, how could it be clear for anyone that<br />

the centre of our commitment is not a rule book<br />

or an ideal, but a deepening friendship with the<br />

Risen Christ?<br />

What are your hopes for the Taiz6lSCM<br />

weekend in Manchester?<br />

In a word: encouragement. When we try to hold<br />

our lives open, and to live with generosity, we<br />

need to know that we are not alone. We need<br />

confirmation. And that comes to us in the peace<br />

of prayet and the understanding of others.<br />

( The church at<br />

Taiz6. Photo by<br />

Solveig Olsson.<br />

SusannahRuilge<br />

didn't expect auteek<br />

inTaizd to lead<br />

where it did.<br />

Autumn 2010. <strong>Movement</strong> . 7

Freedom Featu re<br />

I<br />

m<br />

T-l<br />

I<br />

reedom in my lingua franca called Filipino is translated as<br />

L{ "Kalayaan." A word that is used often and mindlessly such as a<br />

name of a national road., numerous streets, bridges, buildings,<br />

of a pub, even a dormitory in a premier state university. I suppose<br />

the reason for this obsessive use of the word is for people to be<br />

reminded of its noble meaning, its history and intent. Sadly, this<br />

practice has gone awry and lost its potency to a generation ofyoung<br />

people who were born "free" and could not care much about the<br />

sacrifices that generations of people have made to gain freedom for<br />

themselves and the future in our country. The apathy and indiffer-<br />

e<br />

t<br />

dt<br />

;'r<br />

ence that has engulfed the youth of today is indeed debilitating.<br />

Freedom (and the lack or absence thereof) is one ofthose things that<br />

we take for granted until it hits you right in your face. This dawned<br />

I<br />

TF<br />

{rf I<br />

.r# I<br />

:fl<br />

)tl<br />

i!<br />

I'<br />

on me one day on February t2,20I0, when my 62year old uncle, a<br />

retired medical doctor, was arrested by the Philippine Military with<br />

42 other doctors, midwives, nurses while they were conducting a<br />

training for community health workers on emergency response in<br />

the outskirts of Manila, the capital of the Philippines. Without the<br />

knowledge of familyimembers and lawyers, they were brought to a<br />

Military Camp, handcuffed, blind-folded, interrogated and tortured<br />

for neatly a week. The Philippine Military was quick to accuse them<br />

of taking part in armed rebellion saying that the medical workers<br />

were conducting a training to make explosives and arrested them<br />

without a proper warrant. Hell-bent on destroying the credibility of<br />

my uncle and his colleagues, they launched a nationwide vilification<br />

campaign against the 43 health workers. Without any warning, 43<br />

q.,<br />

people lost all their rights and freedom, including my uncle. At first,<br />

I could not believe what had just happened. I was in denial of the<br />

',+<br />

situation until I watched my distraught aunt pleading to the government<br />

to release my uncle on national television. I asked myself<br />

I<br />

)<br />

l:<br />

how could this happen, now that we live in a democracy, now that<br />

we have freedom in the country.<br />

I was making this comparison in reference to an earlier period when<br />

my own father was arrested and became a political prisoner for<br />

nearly 5 years during my childhood for participating in a movement<br />

against the Martial Law of former Philippines Dictator Ferdinand<br />

Marcos from 1972 to 1985. The period of Martial Law was considered<br />

the darkest period in the history of my country, where almost<br />

all the freedom and civil liberties of the people were curtailed.<br />

Thousands were arrested, imprisoned, abducted, disappeared and<br />

killed. The Philippine legislature was closed and mass media was severely<br />

censored. I did not understand much of what was happening<br />

Autumn 2010 . <strong>Movement</strong> " 9

F:reeelorn l:eature<br />

back then. All I could remember was that I was<br />

free to visit my father in prison once a week and<br />

could play freely in the grounds of the Military<br />

detention camp with children of the other political<br />

detainees.<br />

Death Sggms tO<br />

be an acceptablg<br />

Things have changed after the "Popular Uprising"<br />

in February 1986, where I participated as a<br />

young student member of the<br />

StudentChristian<strong>Movement</strong>of<br />

the PhiliPPines. With a PoPular<br />

democraticgovernmentinplace,<br />

consequenceofahostoffreedomsguaranteed<br />

under the PhiliPPine Constitugxpfgssing<br />

and tion of 1987 can be enjoyed<br />

exgfGising yOUf bv the Filipino people' some<br />

- with a relativelY high degree<br />

fregdom of spegch of awareness, such as Freedom<br />

andopinion.ofReligion.orsolthought'<br />

-<br />

TwentY four Years later, with<br />

four democratic Presidents in<br />

succession at the helm, political freedom seems<br />

to have deteriorated gradually rather than improved.<br />

Basic freedom and the civil liberties of<br />

the people are constantly threatened and denied'<br />

Here is why.<br />

Freedom of Expression and Association.<br />

While Filipinos can express their political<br />

thoughts and sentiments in public, they run the<br />

risk of being harassed, intimidated, abducted<br />

and even killed for doing so. Such has been the<br />

case for more than 1,,192 activists and human<br />

rights defenders who have extra-judicially killed<br />

since 2001. Under a democratic government of<br />

President Gloria Macapagal Artoyo, they thought<br />

they had the freedom to express their political<br />

opinions, demand good governance and join political<br />

mass movements. Most of the victims of<br />

the killings belonged to the most progressive political<br />

organization in our country representing<br />

the farmers, students, workers, and even clergy.<br />

Freedom of the Press.<br />

Philippines is the second most dangerous place<br />

for journalists to practice their profession, next<br />

only to Iraq. As I write this article, three journalists<br />

have been killed in a span of six days, making<br />

a total of 103 journalists killed since 2001. In<br />

November 2009, 56 members of the media were<br />

brutally massacred by private armies belonging<br />

to a powerful political clan in one province in the<br />

Philippines. A culture of impunity exists in our<br />

country, where death seems to be an acceptable<br />

consequence of expressing and exercising your<br />

freedom of speech and opinion, even for the<br />

media practitioners.<br />

Freedom of <strong>Movement</strong>.<br />

Sure, Filipinos can travel anywhere in this age of<br />

globalization. They are in fact everywhere in the<br />

world, a good B million Filipino migrants work<br />

and live elsewhere, other than their own country<br />

of birth and nationality. This is propelled by the<br />

Philippine Government's Labor Export Policy<br />

(LEP), where 3,000 Filipinos leave the country<br />

every day to work as domestic helpers, nannies,<br />

nurses, factory workers abroad. Freedom of<br />

movement is relative to those who can affotd it,<br />

but it's hardly a choice for the millions of migrant<br />

workers who leave their families back home to<br />

earn a decent living for their survival. The reality<br />

of the grinding poverty an estimated 30% of<br />

-<br />

the country's population live below the poverty<br />

line and 1-0To of the 92 million population are<br />

unemployed<br />

-<br />

overseas work.<br />

has pushed many Filipinos for<br />

What does Freedom really means for us today? Is<br />

it merely the ability to exercise free will and make<br />

personal choices? Christian praxis has taught us<br />

much about the meaning of Freedom in the contemporary<br />

world. Freedom plays an important<br />

role in my identity as a Christian, it is central to<br />

my understanding of God, in the same breath as<br />

Justice and Peace. In Galatians 5:1-, "Freedom is<br />

what we have-Christ has set us free! Stand, then<br />

as free people and do not allow yourselves to become<br />

slaves again" the awareness of freedom is always<br />

placed within the context of people's experi-<br />

10 . <strong>Movement</strong> " Autumn 2010

I<br />

ence of struggle for liberation from oppression,<br />

marginalization and bondage like the Exodus or<br />

Salvation History in the Bible. It also means that<br />

freedom cannot be separated from the practice<br />

of justice and solidarity. In my opinion, personal<br />

or individual freedom is meaningless when we<br />

are unable to be in solidarity with the people<br />

who are oppressed, marginalized and discriminated.<br />

It also entails confronting the structural<br />

and systemic root causes of injustice that deny<br />

freedom in its entirety. My reflecting on freedom<br />

is a Faith journey, it is an affirmation of my belief<br />

that the God of justice and love is with us as we<br />

walk in solidarity with the people in the margins<br />

in our communities, the migrants and refugees,<br />

politically persecuted, the minorities.<br />

Two months after my uncle's arrest, I was finally<br />

able to visit him in prison in the Military Camp<br />

in the outskirts of the city. Since the arrest, we<br />

have been relentlessly campaigning to stop the<br />

torture and for their immediate release. In the<br />

15 minutes that I was allowed to see him, no<br />

words came out of my mouth. Seeing their miserable<br />

condition inside prison and the sadness in<br />

my uncle's eyes, I just broke down in tears. An<br />

,*<br />

?'1-,llr-rtt<br />

enormous feeling of injustice was swelling inside<br />

me, building-up like the molten lava from underneath<br />

the Earth lookingfor a way to release the<br />

tension, it came out as tears, flowing down my<br />

face. I knew we were up against the most powerful<br />

forces in the land, the Philippines Military<br />

and the Government. The Government, in its<br />

counter-insurgency plan called "Oplan Bantay<br />

Laya" or Operation Guard Freedom, aimed to<br />

wipe out rebellion at all cost, often at the expense<br />

of innocent civilians, and the Military for<br />

implementing the plan with total disregard of<br />

human rights and civil liberties of the people.<br />

Writing this reflection reminds me of the people<br />

whose freedom has been taken away and who<br />

have paid the ultimate sacrifice for freedom, like<br />

my uncle and the 42 co-health workers in the<br />

Philippines, the thousands of political prisoners,<br />

and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, Nobel Prize Winner<br />

for Peace from Burma. Under house arrest and<br />

physically constrained by the ruling Military<br />

Junta, she chose to free her mind and spirit from<br />

the debilitating control of fear to seek freedom<br />

and democracy f.or her country.<br />

^' Protestors<br />

demand the<br />

relese of the<br />

43 imprisoned<br />

health workers.<br />

Photo by<br />

Bulatlat.<br />

NectaMontes<br />

Rocas is from the<br />

Philippines and<br />

works for WSCF<br />

Asia Pacific.<br />

Autumn 2010 . <strong>Movement</strong> . 11

Freedom Feature<br />

A Free Student Life<br />

planning a life away from your parents for the first time? Hattie Hodgson has other<br />

things for You to think about.<br />

) Student life:<br />

all about having<br />

a room as messy<br />

as you want?<br />

Photo by Ben<br />

Babcock.<br />

f| xplore the notion of Freedom from a<br />

H ,t.,d"nt's perspective the task seemed<br />

-<br />

LJ somewhat straight forward. I'm a student,<br />

and I suppose my life is fai:.lry free. However,<br />

when I actually sat at my desk, notes, references<br />

and opinions by my side, I drew a massive blank'<br />

What is freedom? For a concept so widely accepted<br />

across the Western world as a fundamental<br />

human right, it is very hard to pin down' Is<br />

it to be free from something or free to do something?<br />

What does it mean to be free? How does<br />

this relate to me as a student? On one level, the<br />

freedom I gained by moving out of my parent's<br />

house is vast. I am living life on my terms for the<br />

first time: free to stay in bed until midday; to<br />

cook meals at obscure times and to let my bedroom<br />

get as messy as I can bear. These practical<br />

freedoms are liberating, exciting and sometimes<br />

scary- they are the ones that often spring to<br />

mind when we think about freedom as a student'<br />

Frequently forgotten though, are the underlying<br />

freedoms that make my life what it is. Freedoms<br />

of speech, thought, belief and faith are often<br />

taken for granted. Although, they are fundamental<br />

to the lifestyle that most of society leads,<br />

they are so ingrained in our society that they are<br />

rarely thought about let alone questioned' There<br />

is little doubt though that the lifestyle I have as<br />

a student would be very different if they did not<br />

exist.<br />

If you have been paying attention to the SCM<br />

website, you might have noticed the link on<br />

the home page to a YouTube video made by the<br />

members of the Student Christian <strong>Movement</strong> of<br />

Zimbabwe.In the video, the students speak of<br />

being arrested and even beaten for speaking out<br />

against the obvious injustice theywitness around<br />

them<br />

- in particular when campaigningfor fairness<br />

in the elections in 2008. It is apparent that<br />

their lifestyle as students is<br />

vastly different from ours; theY<br />

do not experience the same<br />

fundamental freedom that<br />

we do. The president of SCM<br />

Zimbabwe, quite aPtlY named<br />

Innocent, is quoted on the<br />

Christian Aid website saYing<br />

'There is no freedom of sPeech<br />

in Zimbabwe, because there is<br />

no freedom after sPeech'. Individuals'<br />

opinions are not welcome<br />

unless theY are the same<br />

t<br />

12 . <strong>Movement</strong>'Autumn 2010

Freedom Featu r<br />

t<br />

as the state's. Despite this, the students of Zimbabwe<br />

keep campaigning. In fact, proportionally<br />

a lot more students over there fight to have their<br />

voice heard -<br />

SCM Zimbabwe has around 5,000<br />

On l8th February 1943, however, they were<br />

discovered. Arrested, immediately put on trial<br />

and found guilty of treason, three of the group's<br />

leaders were executed. Moments before he died,<br />

members. Is it the lack of freedom that encour-<br />

one of them cried out: "Let freedom live".<br />

ages them to use their voices and campaign?<br />

The life of a student denied freedom is certainly<br />

Certainly it seems to be the case that, when<br />

faced with an inhibition of freedom, students<br />

are among the first to speak out. The Kent State<br />

shooting in 1970; the Tiananmen Square pro-<br />

very different to the lifestyle I experience. The<br />

superficial liberties that are so exciting and important<br />

to me and my peers are suddenly put into<br />

perspective if you are not allowed to say what<br />

tests in 1989, the uprisings in Iran in 2006: all<br />

are examples of students acting to oppose injus-<br />

you believe. The students in these circumstances<br />

have to fight for their liberty rather than it being<br />

tice. The student voice often provides one of the<br />

handed to them on a plate. They are inspired to<br />

most powerful oppositions in countries and regimes<br />

where freedom is restricted. This is plainly<br />

protest against injustice even though they may<br />

face dire consequences for doing so. Even without<br />

seen in the actions of the White Rose group.<br />

Set up in Munich under Nazi rule, this group of<br />

these restrictions, it does not feel as if students<br />

in the UK are inspired in the same way. Certainly<br />

students published and distributed leaflets con-<br />

we do not use our combined voices as effectively<br />

taining messages opposing the regime. The fi.rst<br />

of these was a printed version of a sermon from<br />

Bishop August von Galen, an outspoken critic of<br />

the Nazi's actions, decrying the euthanasia poli-<br />

as we might, with thoughts of the wider world<br />

often becoming masked by a do-what-l-wantwhen-I-want<br />

attitude. Young people arriving at<br />

university are faced with such extreme libera-<br />

a<br />

cies that had just been implemented in concentration<br />

camps. The Nazis shrouded their policies<br />

with a great deal of secrecy, implementing a<br />

vast array of censorship laws. By publishing the<br />

details of the atrocities that were occurring, the<br />

White Rose were not only educating<br />

the people of Germany,<br />

tion -<br />

often with few contact hours, rules and<br />

responsibilities -<br />

that frequently they do not<br />

know how to cope. With the student dropout<br />

rate getting higher every year, perhaps the student<br />

lifestyle in the UK is just too free?<br />

,:T"t ;Fl. 1<br />

Hattie Hoilgson<br />

has just finished her<br />

first year at Leeds,<br />

studying Managing<br />

Performance.<br />

but also protesting against the<br />

freedom of speech and belief<br />

they severely lacked. They were<br />

breaking the law and putting<br />

l^i<br />

themselves in incredible danger.<br />

The group successfully kept<br />

their anonymity and continued<br />

their campaign for 5 monthsdistributing<br />

leaflets as far as<br />

Stuttgart, Vienna and Berlin.<br />

.( The White<br />

Rose resistance<br />

movement before<br />

their execution in<br />

1 943.<br />

Autumn 2010 . <strong>Movement</strong> . 13

Freedom Feature<br />

The Truth Will Set You Free<br />

phil Bradford discovers a brand of theology founded on freedom and dignity<br />

Black Theologians:<br />

Robert Beckford<br />

(UK), Allan Boesak<br />

(South Africa),<br />

James H. Cone<br />

(USA), Dwight<br />

Hopkins (USA),<br />

Barney Pityana<br />

(South Africa) and<br />

Cornel West (USA).<br />

Dalit Theologians:<br />

Vedanayagam<br />

Devasahayam,<br />

Arvind P. Nirmal,<br />

M.E. Prabhakar<br />

fflhroughout<br />

I<br />

I<br />

history, people have striven<br />

f"t freedom, seeking to escape from situ-<br />

ations which enslave or constrain them.<br />

Such quests have not always been especially honourable,<br />

but fictionalheroes such as Don Quixote<br />

embody a human desire to be independent and<br />

free of subservience to outside forces. Freedom<br />

is a major theme in Christian theology and has<br />

a prominent place in the Bible, not least in the<br />

most prolific of the New Testament authors. ?or<br />

you were called to freedom, brothers and sisters; only<br />

do not use your freedom as an opportunity for selfindulgence,<br />

but through love become slaves to one<br />

another.'So wrote Paul to the Galatians (5:13),<br />

summing up the rather complicated approach<br />

he takes to the issue of freedom throughout his<br />

epistles. Freedom, for Paul, was found in submission<br />

to Christ, even as Christ was the source of<br />

our freedom. Christian freedom did not entail<br />

licence to do whatever an individual wished.<br />

However, Paul's opinion on the subject of actual<br />

bodily freedom was somewhat more ambiguous<br />

in a Roman Empire in which slavery was accepted<br />

and widespread. 'Were you a slave when<br />

called?'he asks in his letter to the Romans (7:21).<br />

'Do not be concerned about it' is his advice. Exactly<br />

what he counsels is unclear, because when he<br />

proceeds to say' even if you can gain your freedom',<br />

the Greek which follows can be translated to give<br />

two entirely different meanings: either 'make use<br />

of your present condition now more than ever' (i.e.<br />

stay a slave) or 'availyourself of the opportunity'.It<br />

is unlikely that he saw it as a pressing question.<br />

What mattered to Paul, in his belief that the end<br />

times were coming very soon, was that people<br />

devoted themselves to living for Christ rather<br />

than becoming distracted by worldly questions<br />

such as being a slave or a free person.<br />

As it became increasingly clear that Jesus would<br />

not return imminently and that the world was<br />

not about to end, the later New Testament<br />

authors became decidedly conservative on the<br />

issue of slavery and personal freedom. The author<br />

of Ephesians commanded slaves to 'obey<br />

your earthly masters with fear and trembling' (6:5;<br />

see also Colossians 3:22), whilst the writer of<br />

Titus thought that slaves ought tobe'submissive<br />

to their masters and to give satisfaction in every<br />

respect'(2:9). Throughout the middle ages, drawing<br />

on Romans 13:1, it would be the themes of<br />

obedience and submission to the king and the<br />

authorities (above all the Church authorities)<br />

which would be the most important in theology.<br />

Even after the Enlightenment, there was no<br />

widespread support for the freedom of humanity<br />

as a whole, and Christianity in particular proved<br />

reluctant to embrace the idea. In the debate<br />

over the abolition of the slave trade, the Bible<br />

provided support for both sides. The fact that<br />

there is very little (if any) explicit condemnation<br />

of the institution of slavery in the text, even in<br />

the New Testament, was problematic for those<br />

arguing that abolition was a Christian duty. The<br />

anti-abolitionists could sustain their campaign<br />

with Biblical evidence, and did so in the bitter<br />

debates in the UKwhich resulted in the abolition<br />

of the slave trade (1807) and slavery (1833) as<br />

well as in the struggle which led to the Civil War<br />

in the United States. Until well into the twentieth<br />

century, the Christian churches continued<br />

to maintain a doctrine of obedience and uphold<br />

traditional teaching on the subjects of authority.<br />

The greatest challenge to such teachings, and<br />

with it to traditional or classical models of theology,<br />

was an attempt to create theologies based<br />

on the concept of human freedom and dignity,<br />

14 . <strong>Movement</strong>. Autumn 20'10

Freedom Feature<br />

il<br />

which came in the second half of the twentieth<br />

century. Perhaps the most significant movement<br />

in this respect is liberation theology, which arose<br />

in staunchly Roman Catholic Latin America. The<br />

'founding father' of liberation theology is usually<br />

considered to be the Peruvian priest Gustavo<br />

Gutilrrez, whose Theology of Liberation (1971)<br />

was the pioneering text which laid the basis for<br />

the work of all subsequent practitioners in the<br />

field. At the heart of liberation theology was the<br />

idea of the 'preferential option for the poor', the<br />

belief that God took the side of the poor and dispossessed<br />

(which was supported theologically by<br />

the Exodus narrative in particular). The emphasis<br />

was placed on 'praxis': theology was informed by<br />

action, not vice-versa. Liberation<br />

theology was essentially<br />

a struggle for freedom by the<br />

majority of poor, often disenfranchised<br />

peoples in Latin<br />

America, which emphasised<br />

that spiritual and material<br />

liberation were inseparable.<br />

It arose in the context of a<br />

continent which was mainly<br />

under right-wing dictatorships<br />

whose basic policy was<br />

to preserve the status quo and the rights of the<br />

wealthy minority. Since liberation theologians<br />

employed Marxist language and models, they<br />

were deemed suspect by these regimes, and were<br />

looked on unfavourably (against the backdrop<br />

of the Cold War) by rabidly anti-Communist elements<br />

in the United States. The most famous<br />

casualty was Oscar Romero, the Archbishop of<br />

San Salvador, a critic of the human rights abuses<br />

of the El Salvadoran military authorities, who<br />

was shot dead whilst celebrating mass in 1980.<br />

Liberation theologians also encountered the displeasure<br />

of the Vatican, especially after the election<br />

of John Paul II in 1978: the Polish Pope was<br />

unable to distinguish between the oppressive,<br />

authoritarian Communist regime in his homeland<br />

and the use of Marxist ideas in a region<br />

subjected to right-wing dictatorships. The then<br />

Liberation theology<br />

was a struggle for<br />

freedomn which<br />

emphasised that<br />

a spiritual and<br />

material liberation<br />

were inseperable.<br />

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger led the campaign<br />

against the liberation theologians, and in 1985,<br />

acting in his role as head of the Congregation for<br />

the Doctrine of the Faith, he imposed a one-year<br />

silence on Leonardo Boff. To their credit, the<br />

Peruvian bishops resisted Ratzinger's attempts<br />

to bully them into denouncing Guti6rrez. It did<br />

not go unnoticed that at the same time as the<br />

Roman Catholic Church was demanding the<br />

right for its own voice of dissent to be heard<br />

in Communist Eastern Europe, it was acting in<br />

exactly the same way as the Communist regimes<br />

when the power dynamic was reversed. And the<br />

Vatican's effort failed to prevent liberation theology<br />

having a significant impact. Other oppressed<br />

groups, such as the Dalits in<br />

India, drew on such models<br />

to create indigenous liberation<br />

theologies applicable to<br />

their own situations. Kim<br />

Chi Ha, a South Korean dissident<br />

and playwright, wrote<br />

The Gold-Crowned Jesus as a<br />

protest against the policies of<br />

his government and the complicity<br />

of the Korean Church.<br />

In the English speaking<br />

world, there were some attempts to apply liberation<br />

theology to a Western context, particularly<br />

in the work of scholars such as John Vincent<br />

and Christopher Rowland in the UK. However,<br />

although there was poverty, especially in the inner<br />

cities, theological struggles for freedom were<br />

principally created by oppressed minority groups.<br />

In the United States, the civil rights movement<br />

of the 1960s led to the development of a specific<br />

tlpe of liberation theology: black theology. Its<br />

proponents asked how classical Christian theology<br />

could possibly address the experiences of<br />

African Americans who were essentially treated<br />

as non-existent and stripped of their dignity by<br />

the racist policies of the southern states. Theologians<br />

such as James H. Cone, the most famous<br />

name in this field, maintained that a return to<br />

Feminist<br />

Theologians:<br />

Kari Borresen<br />

(Norway), Mary<br />

Condren (Ireland),<br />

Mary Daly (USA),<br />

Mary Grey (UK),<br />

Elizabeth Schiissler<br />

Fiorenza (USA),<br />

Dorothee Stllle<br />

(Germany) and<br />

Rosemary Radford<br />

Ruether (USA).<br />

Liberation<br />

Theologians:<br />

Leonardo Boff<br />

(Brazil), Helder<br />

Camara (Brazil),<br />

Gustavo Gutidrrez<br />

(Peru), Ronaldo<br />

Muaoz (Chile),<br />

Oscar Romero (E1<br />

Salvador), Juan Luis<br />

Segundo (Uruguay)<br />

and Jon Sobrino<br />

(Spain/El Salvador).<br />

Autumn 2010. <strong>Movement</strong>. 15

Freedom Feature<br />

Native American<br />

Theologians:<br />

George E. Tinker,<br />

Robert Allen<br />

Warrior and Roy I.<br />

Wilson.<br />

Queer<br />

fheologians:<br />

Marcella Althaus-<br />

Reid (Argentina/<br />

UK), Chris Glaser<br />

(USA), Robert E.<br />

Goss (USA), Gerard<br />

Loughlin (UK),<br />

John J. McNeill<br />

(USA) and Elizabeth<br />

Stuart (UK).<br />

scripture was necessary, in particular a rereading<br />

of the Exodus narrative and the story of Jesus<br />

reaching out to the marginalised through the<br />

eyes of blacks. Black theology, they argued, had<br />

to arise from the specific circumstances of black<br />

oppression. It was a theology which was also<br />

important in South Africa, where the apartheid<br />

regime's policy of white supremacy saw millions<br />

disenfranchised and treated as second-class citizens<br />

simply because of the colour of their skin.<br />

At the same time, women also began to articulate<br />

the way in which theology was essentially a<br />

male-dominated discipline in the development<br />

of feminist theology. Feminist theology emerged<br />

principally from the late 1960s, because it was<br />

only from this period that women began to obtain<br />

the social and cultural freedoms which permitted<br />

them to be taken seriously as theologians.<br />

Despite massive strides towards equality, women<br />

remained at a disadvantage in the secular world<br />

(even in Western Europe, where in Switzerland<br />

- for example -<br />

they would not receive the vote<br />

until 1971), and more so in the Church. Feminist<br />

theologians challenge the forms of theology<br />

which justify male domination and the subjugation<br />

of women, including the use of solely male<br />

language to refer to God and the argument that<br />

only men can serve as leaders in the church. As<br />

with other forms of liberation theology, feminist<br />

theology seeks to challenge the use of theology<br />

as a means to preserve established powers and<br />

hierarchies, in this case the tradition of patriarchy<br />

which permeates the churches. As it is the<br />

Roman Catholic Church which has been most<br />

resistant to the idea of women in the priesthood<br />

and positions of leadership, a significant number<br />

of feminist theologians come from that tradition.<br />

Queer theology developed slightly later. Again,<br />

the starting point was the discrimination experienced<br />

by gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgendered<br />

people at the hands of the dominant heterosexual<br />

majority. It involved rereading Biblical texts<br />

from the perspective of minority, against the<br />

setting of the civil gay rights movement which<br />

saw the gradual decriminalisation of homosexuality<br />

in the West and the end of homosexuality<br />

being treated as some form of illness or deviancy.<br />

It also stressed the way in which sexuality (and<br />

consequently theological discussions of sexuality)<br />

was intricately tied up in social and cultural<br />

prejudice. However, more recent queer theology<br />

is not simply defensive, but instead seeks to<br />

build a positive theology which derives from the<br />

experience of LGBT communities and examines<br />

sexuality anew.<br />

Still other groups, although far smaller in number,<br />

have also started to articulate theologies which<br />

deviate from historic orthodoxies. One of the<br />

most interesting of these is Native American<br />

theology. Whereas liberation theology associates<br />

strongly with the Israelites in the Exodus stories,<br />

Native American theology identifies with the Canaanites,<br />

a people exterminated by the Israelites,<br />

'God's chosen people'. The idea of being 'God's<br />

new elect'was a common one in early modern<br />

Europe and was inherited by those who settled<br />

in the New World; the rhetoric of 'divine plan'<br />

underpinned the European expansion across the<br />

North American continent, at the expense of the<br />

indigenous peoples. Native American theology<br />

seeks to address the consequences ofthis and ask<br />

what it means to be those who find themselves<br />

not to be part of a self-declared divine elect'<br />

Naturally, these theologies meet and overlap,<br />

and the sketch above touches only on some of the<br />

major developments in theologies dealing with<br />

the issue of freedom. They have, of course, been<br />

criticised, and many scholars question whether<br />

liberation theology in particular still has a role<br />

in a post-Communist context. But in a world<br />

in which thousands of millions still live in poverty<br />

and in which women, LGBT people, ethnic<br />

minorities and other groups are still treated unequally<br />

or even persecuted (especially within the<br />

churches), it is easy to see that these theologies<br />

of freedom have a continuing and crucial role in<br />

the struggle to assert the value of each and every<br />

human life on this planet.<br />

lt<br />

'fi<br />

ill<br />

4<br />

16 . <strong>Movement</strong> . Autumn 2010

Mary Grey asks: ls Liberation Theology still relevant for the 21st century?<br />

I r<br />

,l<br />

\<br />

l<br />

L<br />

t<br />

/-l ome years ago, the "founding Father" of<br />

):':,",'*:*",","T';::J::T:"1"i'"':i:<br />

national Conference what he, the "founder", now<br />

thought of Liberation Theology's achievements.<br />

He replied: "The poor are even poorer and the rich<br />

care even less."<br />

Does that mean that Liberation Theology has<br />

failed and is no longer a valuable tool in the<br />

search for justice, freedom and an end to the<br />

vicious spirals of poverty suffered by the poor<br />

Southern countries? Will there be a straightforward<br />

answer to this question?<br />

Dramatic beginnings and key moments<br />

Liberation Theology began with great promise<br />

in Latin America. Even at this distance it seems<br />

to have been an almost incredible fact that the<br />

entire Conference of Bishops of Latin America<br />

(CELAM) committed themselves as a continent<br />

to Liberation Theology at Medellin (Columbia)<br />

in 1968 and then again at Puebla (Mexico), 1979.<br />

Of course, the context of oppressive military<br />

dictatorships and regimes was a catalyst, and the<br />

thousands of ecclesial basic communities was a<br />

source of great support. These both embraced<br />

"option for the poor" with enthusiasm, and were<br />

witness to Liberation Theology's methodology of<br />

empowering people at the grassroots level and<br />

encouraging them to become agents of their own<br />

destiny.<br />

From the outset, it seemed that this way of doing<br />

theology would not be confined to Latin America<br />

alone. Many different countries began to develop<br />

their own insights as to the embedding of Liberation<br />

Theology in their own settings. For example,<br />

Title image by<br />

Luiz Baltar.<br />

Autumn 20'10 . <strong>Movement</strong> . 17

I<br />

Freedom Feature<br />

in India, it has taken a more pluralist character,<br />

since Christianity represents only around 4To of<br />

the population. Even within India there are many<br />

varieties: Dalit Liberation Theology has emerged<br />

as the voice of the "former Untouchables" who<br />

claim to be excluded by the dominant Caste<br />

Hindus. Whereas there are links with the Black<br />

American struggle for equal rights, and with<br />

South Africa's apartheid struggle, many would<br />

claim that Liberation Theology has not taken<br />

root in a major way in the African continent. Yes,<br />

freedom and justice are crucial, but cultural concerns<br />

are more prominent for African identity.<br />

There are two more key moments: the first was<br />

called by Virginia Fabella, (a Filipina theologian)<br />

"the irruption within the irruption" in New Delhi<br />

-<br />

in 1981 at the Conference of the Ecumenical Association<br />

of Third World Theologians. Women<br />

protested that they were doubly oppressed<br />

- by<br />

society's structures and by their own men folk:<br />

the very categories of Liberation theology had<br />

ignored the specific ways in which women experienced<br />

injustice. So Feminist Liberation Theology<br />

was born, and has steadily developed its own<br />

networks regionally and on an international level.<br />

But there was another forgotten dimension -the<br />

earth itself. After the Earth Summit in 1992 the<br />

renowned Liberation theologian, Leonardo Boff,<br />

underwent a conversion, in which he recognised<br />

that the earth was the fundamental focus for<br />

liberation. This was spelt out in his book, Ecology<br />

and Liberation<br />

-<br />

a new Paradigm. As Sallie<br />

McFague<br />

- a feminist liberation theologian -<br />

proposed, nature is the new category of poverty.<br />

It seemed that Liberation Theology was unstoppable:<br />

even in the UK there was a movement<br />

called British Liberation Theology that brought<br />

together disparate groups working with Liberation<br />

Theology methods in diverse ways.<br />

Storm clouds gather<br />

But it was not to be plain sailing as storm clouds<br />

gathered from different quarters. First, Vatican<br />

opposition has made a powerful impact. Not only<br />

was the criticism of using Marxist categories a<br />

major one, but because of the official opposition,<br />

(The Vatican Instruction was written in 1984 by<br />

the future Pope, then Cardinal Ratzinger), but<br />

the appointment of conservative Bishops and<br />

heads of seminaries in Latin America made a<br />

damaging impact. Theologians like Leonardo<br />

Boff and Jon Sobrino (a Jesuit) came under Vatican<br />

scrutiny. The categories of Liberation Theology<br />

also came under fire. "Praxis" was thought to<br />

be too Marxist in tone; "option for the poor" was<br />

considered to be too particular and reductive for<br />

theology, too exclusivist what should happen<br />

-<br />

to the rich? Did God not want them too? The<br />

idea of the "poor" taking power, was thought to<br />

be too similar to Niezsche's "will to power". What<br />

happened to the peaceful and other-worldly attitude<br />

of Christ to power?<br />

There were also internal critiques within Liberation<br />

Theology itself. Had the theologians become<br />

too involved in "talk" and not in "action"? In<br />

interpreting the world and not changing it? In<br />

any case, in Latin America, politics had moved<br />

on: some military dictatorships such as Chile<br />

-<br />

had given way to socialist governments. The<br />

-<br />

war in El Salvador and Guatemala was over. At<br />

the same time, Pentecostalism seemed to have<br />

overtaken Liberation Theology in popularity in<br />

Latin America; whereas in Europe after 1989,<br />

and the fall of communism, capitalism appeared<br />

to reign supreme. There was now no alternative<br />

system. The 1990s became a decade of crisis for<br />

Liberation Theology. What could be salvaged?<br />

Signposts for the future<br />

The first point is that there is a fundamental<br />

authenticity about the approach of Liberation<br />

Theology. The Bible is permeated with the need<br />

to work for justice for the poor and vulnerable,<br />

from the teaching of the Jewish prophets, to<br />

Mary's Magnificat and the Sermon on the Mount.<br />

Catholic Social teaching from the Encyclical Rerum<br />

Novarum in 1893 has focused for more than<br />

a hundred years on social justice. Christian his-<br />

18 . <strong>Movement</strong> . Autumn 2010

Freedom Feature<br />

tory is full of prophetic figures from all denomi- Clearly a Human Rights-based approach will have<br />

nations who protest against abuse of power and a place in this new direction that Liberation Thestructures<br />

that oppress the poor, from Francis of ology takes. It may be flawed and inadequate, but<br />

Assisi, to the origins of Quakerism, to the Peace it has taken a long historical struggle to achieve<br />

movements that emerged after the World Wars and at the moment is the only international lan-<br />

I and II.<br />

guage of justice and freedom that we can share.<br />

secondly, it is unarguable that Christian NGos ..t^"''<br />

t argue that we need more and propose that<br />

(christian Aid, Cafod, Tearfund, sciaf in the uK "Reconciliation" is the place to which Liberation<br />

Theology brings us' Reconciliation has had a bad<br />

and. agencies like Misereor in Germany), have<br />

press with, activists because it has sometimes<br />

been inspired by the methodorogy of Liberation<br />

Theology both in their educational programme, -""t: a, sell-out with regard to justice' People -<br />

women have been forced to forgive<br />

and projects. They have been able to move on :to":ottl -<br />

f1r the sake of peace' Yet' rightly viewed' I see its<br />

from a more patronising approach of "helping the<br />

because it both offers the goal of the<br />

poor" to enabling poor communities to b"irrr" :Too:t""t",<br />

otltt* of peace and justice as well as the way<br />

agents of their own transformation. Liberation<br />

n *: freedom struggle may be lost or won'<br />

analysis has also been able to reach out beyond lt<br />

warri:lg factions then need to learn how to<br />

Christian categories to enable .o"litior* in :ut<br />

secular society: Jubilee 2000<br />

live together in one land' Rwanda is a poignant<br />

case in point. The Tutsis unmight<br />

not have been able to Reconciliation has a", nr"r,a"r,. n",rt Kagame<br />

be such a success without its<br />

base in Liberation Theology had a bad pfgss<br />

were able to end the formal<br />

- "cancel the debts"being a With aCtiviStS :;Tj;:";"i;:U;::*:;<br />

biblical principle drawn from<br />

Leviticus 19. because it has the Hutus who slaughtered<br />

- their families so brutally?<br />

Thirdly, it is also true that SOmgtimgS mgant a<br />

- This turns the argument<br />

Liberation Theologv can sell-out with rggard ,o *" ,rr.,e of power and<br />

learn from some of the criticisms<br />

to adopt a more flex-<br />

ible approach if it is to be of<br />

tO iuStiGe'<br />

violence' To struggle under<br />

he inspiration of Liberation<br />

*"-".ltt re-named as Reconciliation theology'<br />

use in widely disparate contexts that bear little<br />

resemblance to its own origins. For example, the or Liberation for the long haul - the name may<br />

not be the,vital category- is to re-think the kind<br />

Exodus symbol has been widely used. There has<br />

of power that is effective in achieving the goal of<br />

been a call for a new Moses to lead the oppressed<br />

out of "Egwt" to the promised Land. But what n."it"'It is to admit the truth-force of the nonmeaning<br />

has this, for example, in the context :i"t":t<br />

of the current Palestinian suffering, where the<br />

t::lttt"' practiced by Jesus' and others'<br />

like c.aldhi' inspired by him' The patient livingindigenous<br />

people do not want to go, but to have<br />

out of alternate forms of power as non-violence<br />

their right to stay in their own land recognised? may be ker to the practice of reconciliation<br />

fe<br />

what meaning has Exodus in the contemporary in pursuit of justice' As I hinted in the beginning'<br />

are not simple: struggling with com-<br />

enslavement to and idolatry of the Market, to tl" Tt*"1t<br />

money and profit? would not "Babylon" be a bet- l*Ttlt ld.ambisuity<br />

may be part of the answer'<br />

christian terms what we can trust' is that<br />

ter symbol, in the sense of idolatry of the "Beast" 1"1'<br />

God is :"<br />

in the process of reconciliation' as God<br />

of the Book of Revelation?<br />

was in Christ, reconciling the world to God's self.<br />

ProfessorMary<br />

Grey is an ecofeminist<br />

liberation<br />

theologian and professional<br />

research<br />

fellow at St Mary's<br />

University College,<br />

Twickenham.<br />

Autumn 2010 . <strong>Movement</strong> . 19

ee<br />

Perspectives<br />

JamesTebbut<br />

is...<br />

il ll yexperiencesinPrisonandUniversity munity, and a working with others. I cannot<br />

l\ / | Chaplaincies (there were some differ- now imagine being a chaplain in anything other<br />

I V I encesl) would suggest that chaplaincy than a multi-faith team; and as part of a wider<br />

can be offered in an infinite variety of contexts Student Services department; and in network<br />

and ways. For me, though, the offering of care or partnership with congregations and student<br />

and safe space would be two core principles.<br />

'care' means valuing each member of the institu- :""tt:"t<br />

societies (not least the wonderful SCM!). Whilst<br />

of course arise with multi-party worktion<br />

without exception, and<br />

ing' the diversity involved can lead to a greater<br />

responding appropriatery to ,Safe spacet is #::':::"#,lrlll "*|]-<br />

their needs with as much love<br />

andskilledlistening"r.""o" Something that We ::'":,:T::]::::,*t"T::<br />

chaDlarncv snould not restrrct<br />

musteredordeveloped' Iusu- can all carry with<br />

,n.-r"trr", to a single buildally<br />

failed!; and of course only<br />

managed to .o.,r,".t ;; us as part of our<br />

ing' the work of chaplaincv'<br />

sma' proportion of the Uni- discipleship. ;Jj:1il:';:1;11T::<br />

versity's 30,000 staff and stuconfined<br />

to chaplains alone.<br />

dents. Nonetheless, pastoral encounters were at<br />

the heart of my chaplaincy experience. It might Thus whilst the Chaplaincy itself can hopefully<br />

involve a chance encounter on the way to the Un- be a safe place, 'safe space' is something that we<br />

ion shop, or the longer accompanying that was can all carry with us, as part of our discipleship<br />

sometimes required. It might involve a familiar and the people that we become. The meaningful<br />

face and faith perspective, or sometimes neither. conversations over a cup of coffee, or the SCM<br />

Ithinkof conversationswiththosenewlyarrived meeting or meal, or the Chaplaincy Eucharist,<br />

from China, for whom 'God', let alone 'Christian- are all moments when, with care, we can become<br />

ity', was an alien concept, yet who needed to be safe enough together, and therefore free enough,<br />

aff,rmed and welcomed without precondition; or to explore life's meaning and faith's possibilities.<br />

I think of British and foreign students homesick It is those moments that we can know that we<br />

beyond measure, or facingdomestic violence, for are caredfor and loved, above all by the God who<br />

whom the Chaplaincy service, through adver- invites each of us to share in God's ministry, by<br />

tisement or referral, became an initial safe space. challenging spaces that are neither free nor safe,<br />

Like listening, 'safe space' also requires skilled .,ililJ:-:lturing<br />

reflection as to what it might truly mean. As<br />

a minimum, it does not involve imposition or<br />

pressure, but it does involve hospitality, com-<br />

spaces that are' in order that all<br />

"may rrave trfe, and life in all its fullness".<br />

20 o <strong>Movement</strong> . Autumn 2010

ON<br />

ChaV/ai<br />

T,'r my own fault -<br />

I<br />

I always wanted to be a<br />

university chaplain. It's not that I had any<br />

I rr"ry clear idea what they did, exactly. It was<br />

more that the chaplains I met during my own<br />

student days and after tended to be the kind of<br />

Christian I wanted to be- open to questioning,<br />

sympathetic but challenging, able to analyse and<br />

discuss faith without reducing it to an academic<br />

exercise. If vocation ever makes sense, then academic<br />

chaplaincy made sense of who I was and<br />

the Church I wanted to belong to.<br />

One term in, it's still making sense. There's been<br />

a lot to get used to: adjusting to the difference<br />

between institutions (I was a student at Cambridge<br />

at the end of the 1980s, which shaped<br />

my assumptions about chaplaincy in ways which<br />

don't always translate to a bigger and younger<br />

university); working with expectations (mine,<br />

my church's and my university's) of what a chaplain<br />

is. The world, the church and the 'academy'<br />

have all changed radically in the 20 years since<br />

my graduation, and the role of faith in those<br />

places has shifted in huge ways.<br />

Cultural changes affect the way it's possible to<br />

do chaplaincy, too. Do chaplains still prop up the<br />

college bar all night or would today's anxious,<br />

-<br />

deadline-ridden, career-focused students have<br />

gone to bed hours ago? My own college chaplain<br />

made a point of visiting every first-year student<br />

in their room. Concerns over privacy, not to<br />

mention the dreaded swipe-card access system,<br />

make that approach unthinkable now<br />

Some things don't change. The struggle between<br />

certainty and doubt, doctrinal basis or dangerous<br />

liberalism, looms as large as ever. There's still<br />

a place for discussion, for passionate argument<br />

about points of principle, and the chaplain still<br />

has a valuable role, not in giving answers or controlling<br />

the debate but in helping create spaces<br />

for the right questions to emerge- but while I'm<br />

convinced that 'just sitting talking' adds value<br />

to the university experience, it's not a value you<br />

can easily quantify. Whether your university is<br />

an ancient seat of 'religion and learning' (however<br />

much the fellows hate that description) or a<br />

monument to secular rationalism, chaplains are<br />

the ones who ensure that other voices are heard.<br />

But whose voice? Is chaplaincy still inclusive and<br />

welcoming to the unhappy, the inadequate and<br />

the dorky, or are they all locked in their rooms<br />

communing with Facebook? Chaplaincy would<br />

probably collapse overnight without electronic<br />

communication, but someone also needs to<br />

be available in the middle of the night for the<br />

student desperate to communicate with a real<br />

human being.<br />

Now more than ever, perhaps, chaplains enable a<br />

debate to take place, within and beyond the university,<br />

about what it means to be human, and<br />

the role of faith in encouraging us to discover our<br />

humanity. Chaplains have always known that<br />

religion is at its most alive on the margins, both<br />

of the church and of society. Our role is to make<br />

that a bearable place to be and to encourage<br />

-<br />

the rest of the church to catch us up.<br />

RowanWilliamsis<br />

Anglican Chaplain<br />

at York University .<br />

Autumn 2010 . <strong>Movement</strong>. 21

AnilyTreharneis<br />

a Ph.D. student at<br />

Southampton, and<br />

is actively involved<br />

in their SCM group.<br />

uring my time at university in Southampton,<br />

I've been privileged to be part<br />

of the Chaplaincy community here.<br />

I've seen our chaplaincy change from being a<br />

building only inhabited by user groups to an active<br />

community of people from many different<br />

backgrounds, ages and courses. Being part of<br />

this community has helped to shape who I am<br />

now, what I believe and has given me some of<br />

the best friends who I hope to keep for a lifetime.<br />

The sense of community support was something<br />

that got me through some of myworse times and<br />

I know that's true of manY others'<br />

Of the people I've met in Chaplaincy, the overriding<br />

feeling that they have is one of welcome and<br />

of a community that will support you no matter<br />

what has gone on in your life. It's important to<br />

share in the good times as well as the bad. Some<br />

have described our Chaplaincy to me as being<br />

like some of the earliest Christian communities.<br />

A group of people who eat, drink, socialise and<br />

worship together, living out Christ's message of<br />

loving our neighbour as ourselves. For me, the<br />

purpose of a Chaplaincy should not just be about<br />

providing space for worship on campus or support<br />

when you are down although it should do<br />

both of these things. It should be about nurturing<br />

an active community that people can interact<br />

with, not just'providing a service'. Obviously all<br />

Chaplaincies provide an element of pastoral support<br />

and this is a vital part of their mission on<br />

campus. However, I know many people who've<br />

drawn support not only from our Chaplains but<br />

also from our community and for some, that's<br />

why they're still at university and feel able to<br />

complete their studies.<br />

Chaplains are, of course, a vital part of any Chaplaincy.<br />

They offer the Chaplaincy their wisdom,<br />

expertise and pastoral support. The most effective<br />

Chaplains I've seen have provided all these<br />

things whilst also enabling students to form<br />

communities to support this vital work and going<br />

out into the university and engaging with<br />

students in their own environment. For many<br />

students, this is often the pub. I often wonder<br />

how many deep, life changing conversations I've<br />

had in church compared to over a cup of tea or a<br />

pint with a good friend.<br />

Our largely but not exclusively Christian community<br />

has brought many to consider Christianity<br />

in a new way. Our communion services have<br />

offered people a taste of experiencing worship on<br />

a smaller, more intimate scale and in a different<br />

way to being part of a large church where it can<br />

often be diff,cult to find your place. After finding<br />

a home in Chaplaincy, some have decided to<br />

become Christians, having a sense of belonging<br />

before they believe. It is also important to me,<br />

however, that non-Christians also continue to<br />

feel welcome and not constantly feel like we're<br />

trying to convert them. A community based<br />

around simply telling people things that they<br />

must then believe lacks a respect for individuals<br />

who should be made to feel welcome. Some<br />

have said to me that they've felt some churches<br />

are only being nice because they wanted them<br />

to become Christians, not because they valued<br />

them individually and genuinely wanted to interact<br />

with them. This, I think, is one of the main<br />