Omni College Plus Up to October 2019

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

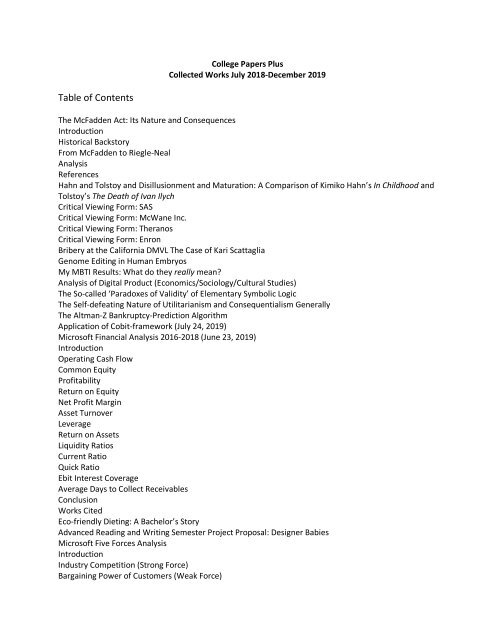

<strong>College</strong> Papers <strong>Plus</strong><br />

Collected Works July 2018-December <strong>2019</strong><br />

Table of Contents<br />

The McFadden Act: Its Nature and Consequences<br />

Introduction<br />

His<strong>to</strong>rical Backs<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

From McFadden <strong>to</strong> Riegle-Neal<br />

Analysis<br />

References<br />

Hahn and Tols<strong>to</strong>y and Disillusionment and Maturation: A Comparison of Kimiko Hahn’s In Childhood and<br />

Tols<strong>to</strong>y’s The Death of Ivan Ilych<br />

Critical Viewing Form: SAS<br />

Critical Viewing Form: McWane Inc.<br />

Critical Viewing Form: Theranos<br />

Critical Viewing Form: Enron<br />

Bribery at the California DMVL The Case of Kari Scattaglia<br />

Genome Editing in Human Embryos<br />

My MBTI Results: What do they really mean?<br />

Analysis of Digital Product (Economics/Sociology/Cultural Studies)<br />

The So-called ‘Paradoxes of Validity’ of Elementary Symbolic Logic<br />

The Self-defeating Nature of Utilitarianism and Consequentialism Generally<br />

The Altman-Z Bankruptcy-Prediction Algorithm<br />

Application of Cobit-framework (July 24, <strong>2019</strong>)<br />

Microsoft Financial Analysis 2016-2018 (June 23, <strong>2019</strong>)<br />

Introduction<br />

Operating Cash Flow<br />

Common Equity<br />

Profitability<br />

Return on Equity<br />

Net Profit Margin<br />

Asset Turnover<br />

Leverage<br />

Return on Assets<br />

Liquidity Ratios<br />

Current Ratio<br />

Quick Ratio<br />

Ebit Interest Coverage<br />

Average Days <strong>to</strong> Collect Receivables<br />

Conclusion<br />

Works Cited<br />

Eco-friendly Dieting: A Bachelor’s S<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

Advanced Reading and Writing Semester Project Proposal: Designer Babies<br />

Microsoft Five Forces Analysis<br />

Introduction<br />

Industry Competition (Strong Force)<br />

Bargaining Power of Cus<strong>to</strong>mers (Weak Force)

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Moderate Force)<br />

Threat of Substitutes (Weak Force)<br />

Threat of New Entrants (Moderate Force)<br />

Conclusion<br />

Wittgenstein on Language and Thought (Philosophy)<br />

Camus and Schopenhauer on the Meaning of Life (Philosophy)<br />

Are Late-term Abortions Ethical? (Philosophy)<br />

Exploring Music<br />

Assignment 1<br />

Second Music Assignment JG<br />

Music Assignment (Assignment 1 Resubmission) for J.G.<br />

Schopenhauer on Human Suffering<br />

Bertrand Russell on the Value of Philosophy (Philosophy)<br />

The Philosophical Value of Uncertainty (Philosophy)<br />

Logic Homework: Theorems and Models (Philosophy/Logic)<br />

Searle vs. Turing on the Imitation Game (Philosophy)<br />

Hume, Frankfurt, and Holbach on Personal Freedom (Philosophy)<br />

Manifes<strong>to</strong> of the University of Wisconsin, Madison Secular Society (Publicly Delivered Speech)<br />

Michael’s Analysis of the Limits of Civil Protections (Philosophy)<br />

Bentham and Mill on Different Types of Pleasure<br />

Set Theory Homework (Formal Logic)<br />

Aris<strong>to</strong>tle on Virtue: Final Exam (Philosophy)<br />

Nagel On the Hard Problem (Philosophy)<br />

Two Papers on Epistemology: Gettier and Bostrom<br />

Examination Questions for a Graduate Philosophy Course (Philosophy)<br />

Camus and Nagel on the Meaning (or Lack thereof) of Life (Philosophy)<br />

Camus’ Hero as Rebel without a Cause (Philosophy)<br />

Can we trust our senses? Yes we can (Philosophy)<br />

Descartes on What He Believes Himself <strong>to</strong> Be (Philosophy)<br />

The Role of Values in Science (Philosophy)<br />

Modern Science (Philosophy/His<strong>to</strong>ry/General Science)<br />

Kant’s Moral Philosophy (Philosophy)<br />

Five Short Papers on Mind-body Dualism (Philosophy)<br />

Arguments Concerning God and Morality (Philosophy/Religion)<br />

Introduction<br />

Two preliminary points:<br />

The Standard Arguments for God’s Existence<br />

Paradoxes Relating <strong>to</strong> God<br />

Is God Necessary for Morality?<br />

Agnosticism vs. Catholicism (Public Address)<br />

God’s Foreknowledge and Moral Responsibility (Philosophy)<br />

The Paradox of Religions Institutions (Religion/Theology)<br />

What is The Good Life? (Philosophy)<br />

J.S Mill on Liberty and Personal Freedom (Philosophy)<br />

Agnosticism vs. Catholicism (Public Address)<br />

Five Short Papers on Mind-body Dualism (Philosophy)<br />

Aris<strong>to</strong>tle’s Conception of the Good Life (Philosophy)<br />

Logic Lecture for Erika (Formal Logic)

Why Moore’s Proof of an External World Fails (Philosophy)<br />

Ethics Posting (Philosophy)<br />

Nagel On the Hard Problem (Philosophy)<br />

Two Papers on Epistemology: Gettier and Bostrom<br />

Examination Questions for a Graduate Philosophy Course (Philosophy)<br />

Three Essays on Medical Ethics (Philosophy)<br />

Mill vs. Hobbes on Liberty (Politics/Philosophy)<br />

Exam-Essays on the Moral Systems of Mill, Bentham, and Kant (Philosophy)<br />

A Defense of Nagel’s Argument Against Materialism (Philosophy)<br />

Nietzsche and Schopenhauer on the Meaning, or Lack thereof, of Life (Philosophy)<br />

Notes on Nietzsche for Sandra (Philosophy)<br />

Nietzsche on Punishment (Philosophy/Politics)<br />

Tracy Latimer’s Father had the Right <strong>to</strong> Kill Her<br />

Towards a doctrine of generalized self-defense (Philosophy/Current Events)<br />

A Utilitarian Analysis of a Case of Theft (Philosophy/Applied Ethics)<br />

Van Cleve on Epistemic Circularity (Philosophy)<br />

Pla<strong>to</strong>’s Theory of Forms (Philosophy)<br />

Early Modern Scientific Thought (Philosophy/General Science)<br />

An Ethical Quandary (Philosophy/Ethics)<br />

Superorganisms (Philosophy)<br />

Camus and Nagel on the Meaning (or Lack thereof) of Life: Long Version<br />

Clifford on Freedom (Philosophy)<br />

Different Perspectives on Religious Belief: O’Reilly v. Dawkins. v. James v. Clifford (Philosophy)<br />

Four Short Essays on Truth and Knowledge (Philosophy)<br />

The On<strong>to</strong>logical Argument: A Concise Explanation (Philosophy)<br />

The Tuskegee Experiment A Rawlsian Analysis (Philosophy/Current Events)<br />

Three Short Philosophy Papers on Human Freedom (Philosophy)<br />

Explain Stace’s ‘Compatibilism’. What is the major objection <strong>to</strong> that view and how would Stace deal with<br />

that objection?<br />

What is Galen Strawson’s ‘Basic Argument’ for our not being free? Does that argument go through?<br />

What evidence is there that the psychologically realm is causally deterministic?<br />

Kant’s Ethics (Philosophy)<br />

Blaise Pascal and the Paradox of the Self-aware Wretch (Philosophy)<br />

Three Short Papers on the Advent of Modern Science (Philosophy/General Science)<br />

Two Problems with the Hypothetico-deductive Method of Confirmation (Philosophy)<br />

Aris<strong>to</strong>tle on Virtue (Philosophy)<br />

Absolute Truth: What it is and how we know it (Philosophy)<br />

Different Perspectives on Religious Belief: O’Reilly v. Dawkins. v. James v. Clifford (Philosophy)<br />

Schopenhauer on Suicide (Philosophy)<br />

Schopenhauer’s Fractal Conception of Reality (Philosophy)<br />

Theodore Roszak’s Epistemology, Bicameral Consciousness, etc. (Anthropology)<br />

Locke, Aris<strong>to</strong>tle and Kant on Virtue (Philosophy)<br />

Different Perspectives on Religious Belief: O’Reilly v. Dawkins. v. James v. Clifford (Philosophy)<br />

Reflection Paper: Harvey on Commodity Fetishism (Politics/Economics)<br />

Reflection Paper: Defending Marxist Economist (Politics/Economics)<br />

Outline of Economics Paper on Contradictions in Free Market (Economics)<br />

Some Reflections on the Virtues of the Free Market (Economics/Politics/Current Events)<br />

When is wealth-redistribution legitimate? (Economics/Philosophy)

An Economic Argument for Drug-legalization (Economics)<br />

Hobbes, Marx, Rousseau, Nietzsche: Their Central Themes (Politics/Philosophy/Intellectual His<strong>to</strong>ry)<br />

De Tocqueville on Egoism (Politics/His<strong>to</strong>ry/Philosophy)<br />

Would the Founding Fathers Approve of Trump? (Politics/Current Events)<br />

The Most Basic Principles of Knowledge Management<br />

The ‘Free’ Market Isn’t Always So Free<br />

An Analysis of Barry Deutsch’s ‘Really Good Careers’ (Economics/Current Events)<br />

Knowledge Management and Information Economics in Relation<br />

<strong>to</strong> the Optimization of Instruction-markets (Economics/Business/Graduate Work)<br />

Chapter 1 Introduction <strong>to</strong> the Study<br />

Introduction<br />

Background <strong>to</strong> the Study<br />

Problem Statement<br />

Purpose of the Study<br />

Research Questions<br />

Advancing Scientific Knowledge and Significance of Study<br />

Rationale for Methodology<br />

Nature of the Research Design for the Study<br />

Research Questions<br />

Definitions of Terms<br />

Assumptions, Limitations, Delimitations<br />

Summary and Organization of the Remainder of the Study<br />

References<br />

Goldman, Rousseau and von Hayek on the Ideal State (Politics)<br />

Take-home Exam on Russian His<strong>to</strong>ry (Politics/His<strong>to</strong>ry/Current Events)<br />

Did the founding fathers support or oppose democracy? Was the Constitution a democratic document<br />

or an anti-democratic document? (His<strong>to</strong>ry/Politics)<br />

The Two Faces of China’s Negative Soft Power:<br />

China’s Belt and Road Initiative as a Case of Negative Soft Power (Politics)<br />

Interest Groups and Political Parties (Politics/Current Events)<br />

France<br />

Russia<br />

What led <strong>to</strong> the collapse of the Soviet Union? (Politics/His<strong>to</strong>ry/Current Events)<br />

Pla<strong>to</strong>’s Republic as Pol Potist Bureaucracy (Politics/Philosophy)<br />

Politics and Contemporary France and Russia (Politics/Current Events)<br />

Politics in the USA, Russia and France<br />

Harvard University Political Science Take-home Exam<br />

Political Parties in the United States: A Brief His<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

France’s Political System<br />

Russia’s Geography in Relation <strong>to</strong> its Political Development<br />

The Collapse of the Soviet Union?<br />

Russia’s Current Political System<br />

Russia’s Dependence on Strong Leaders<br />

Summary of Politics of Economic Growth in the States (Economics)<br />

Should the US have entered WWI? (His<strong>to</strong>ry)<br />

Mill and von Hayek on Free-market Economics (Economics/Philosophy)<br />

How is Colonialism different from Imperialism? Short Version (Politics)<br />

How is Colonialism different from Imperialism? Long Version (His<strong>to</strong>ry/Politics/Economics)

Was the US a World Leader Between 1946-1991? Long Version (His<strong>to</strong>ry/Politics)<br />

A Case for Environmental Regulation and against Carbon Taxes (Economics/Politics)<br />

Wolls<strong>to</strong>necraft vs. Marx on Religion (Intellectual His<strong>to</strong>ry)<br />

Galileo and Wolls<strong>to</strong>necraft on Religion (Religion/Intellectual His<strong>to</strong>ry)<br />

Carbon Taxes vs. Standing Regulations (Economics/Politics)<br />

Culture and Creativity (Sociology)<br />

The American Dream (Politics)<br />

Knowledge-capital (Politics/Economics/Philosophy)<br />

Four Essays on Modern His<strong>to</strong>ry (His<strong>to</strong>ry/Politics)<br />

Why is the United States so Energy-inefficient? (Sociology)<br />

Stalin’s Nationalism vs. Putin’s Nationalism (His<strong>to</strong>ry/Politics)<br />

The Economic Consequences of Minimum Wage (Economics/Public Policy)<br />

Why Minimum Wage is Wrong<br />

Pot Legalization in California: Prop 64 (Current Events)<br />

Zara’s Supply-chain Efficiency (Business)<br />

Microsoft Financial analysis 2016-2018 (Business/Accounting)<br />

Introduction<br />

Operating Cash Flow<br />

Common Equity<br />

Profitability<br />

Return on Equity<br />

Net Profit Margin<br />

Asset Turnover<br />

Leverage<br />

Return on Assets<br />

Conclusion<br />

Sources<br />

Case Studies in Corporate Fraud (Accounting/Fraud Examination)<br />

The Fraud Triangle<br />

Forensic Accounting Post-Enron (Business/Accounting)<br />

Using the Fraud Triangle <strong>to</strong> Prevent Fraud<br />

Money Laundering: Basic Principles (Business/Accounting)<br />

The Valeant Fraud<br />

An Actual Case of ID Theft<br />

A Case of Financial Fraud at a University<br />

The Olympus Fraud<br />

The Dixon Fraud<br />

Multinationals in Relation <strong>to</strong> the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act in Relation<br />

The ARCP Fraud<br />

The Basia Skudrzyk Fraud<br />

The Liberty Bell Fraud<br />

A Hypothetical Skimming Case<br />

Fraud Risk Fac<strong>to</strong>rs in a Hypothetical Multinational Company<br />

Cybercrime: How <strong>to</strong> Spot It and S<strong>to</strong>p It<br />

Fraud Interview Techniques<br />

Some Key Obstacles <strong>to</strong> Effective Fraud Risk Assessment<br />

Five Characteristics of Reliable Employees<br />

The “So What?” About your Industry Analysis (Business)

Analytical Assessment of Greg Toppo’s “Do Video Games Inspire Violence?”<br />

Why Barings Fell (Business/Economics)<br />

Internet Crime (Computer Security)<br />

Privatization in African Telecommunications<br />

Ethio Telecom Being Privatized (Business)<br />

The Economic Justification for America’s Involvement in WWI (Economics/His<strong>to</strong>ry)<br />

The Economics of Higher Education in the 21st Century (Economics/Business)<br />

The Economics of Higher Education in the 21st Century<br />

Part I<br />

Introduction <strong>to</strong> Part I<br />

Retention-rates and Graduation-rates: Introduc<strong>to</strong>ry Remarks<br />

Do Graduation- and Retention-rates Matter?<br />

Open-market Companies (OMC’s): How they Differ from Universities<br />

<strong>College</strong>s Sell Degrees, not Instruction<br />

Enrollment-rates Matter: Retention- and Graduation-rates Don’t<br />

Universities: Their Distinctive Business-model<br />

How Useful Do Students Really Want Their Educations To Be?<br />

The Paradox of Macroeconomic Efficiency<br />

When in Doubt, Drop Out: Dispelling the Myth that Only Losers Drop Out<br />

Knowledge-management: Introduc<strong>to</strong>ry Remarks<br />

Why Knowledge-management Cannot be of Assistance <strong>to</strong> Universities<br />

Key Points<br />

Conclusion of Part 1: How <strong>to</strong> Maximize Revenue by Optimizing Education<br />

The Economics of Higher Education in the 21st Century Part II<br />

Introduction <strong>to</strong> Part II<br />

What is Knowledge-management (KM)?<br />

An Actual Company that Could Benefit from KM<br />

Who Exactly Sounds the KM-alarm?<br />

KM as Preventative Measure<br />

KM in Relation <strong>to</strong> Organizations that Sell Results<br />

KM in Relation <strong>to</strong> Organizations that Sell Services<br />

Service-organizations Depend on Poor KM<br />

KM Impossible Unless Employment and Pay are Performance-dependent<br />

No KM without Financial Transparency<br />

Expense-padding in Relation <strong>to</strong> KM<br />

A Corollary: Education Must be Digitized Whenever Possible<br />

DMO: A New and Better Kind of University<br />

All Accreditations Examination-based<br />

How DMO Turns Non-STEM Students in<strong>to</strong> STEM Students<br />

Emphasis on Instruction as Opposed <strong>to</strong> Selection<br />

More Degree-levels at DMO<br />

Instruc<strong>to</strong>rs Never <strong>to</strong> Function as Gatekeepers<br />

Payments <strong>to</strong> Go Straight from Student <strong>to</strong> Instruc<strong>to</strong>r<br />

The Inverted Payment Pyramid<br />

25 Desiderata that DMO Must Satisfy<br />

Conclusion of Part 2<br />

Conclusion of the Present Work<br />

United Airlines vs. Alaska Airlines (Business)

Air Koryo VS United Airlines (accompanied by pho<strong>to</strong> of the smoldering wreckage of a crashed plane)<br />

Four Papers on Business-theory: Marketing Strategy, Joint Venture, Counter-trade, Ethnocentric Staffing<br />

What is strategy? How does strategy relate <strong>to</strong> a firm's profitability?<br />

What is a joint venture? What type of joint venture is most common? Provide an example of a joint<br />

venture.<br />

Explain countertrade and its purpose<br />

Why should a firm pursue an ethnocentric approach <strong>to</strong> staffing? What are the disadvantages of this<br />

approach? Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of a polycentric approach <strong>to</strong> staffing.<br />

The Secret of IKEA’s Success (Business)<br />

Strategy and Profitability (Business)<br />

Facebook: Why and How it Makes Money (Business)<br />

Gret Satell on Marketing (Business)<br />

An Exercise in Rational Decision-making (Business)<br />

Organizational Analysis of McDonals<br />

Including SWOT Analysis (Business)<br />

Analysis of Case 2: Why the Candidate Should Decline the Job Offer (Business/Ethics)<br />

Internal vs. External Stakeholders: An Analysis of Three Companies (Business/Finance)<br />

Variables in a Marketing-study (Business)<br />

Target: Corporate Case-study (Business)<br />

Prejudice as Psychological Resistance (Psychology)<br />

A Freudian Analysis of Prejudice (Psychology)<br />

Freud on Sublimation: Why His Analysis is Still Relevant (Psychology)<br />

Failure <strong>to</strong> Sublimate: A Freudian Analysis of the Peter Pan Syndrome (Psychology/Current Events)<br />

Psychology Assignment (Psychology)<br />

Attachment Theory and Mental Illness (Clinical Psychology)<br />

Why We Lie (Psychology/Evolutionary Theory)<br />

Unconditioned Stimuli (Psychology)<br />

Goring and Lombroso on Criminality (Psychology)<br />

The Chinese Mitten Crab: Portrait of an Invasive Species (Science: General)<br />

Meiosis and Mi<strong>to</strong>sis (General Science)<br />

Confounding Variables (General Science)<br />

Modern Science (Philosophy/His<strong>to</strong>ry/General Science)<br />

Evidence in Favor of Global Warming (General Science)<br />

Evolution Simply Explained (General Science)<br />

Early Modern Scientific Thought (Philosophy/General Science)<br />

Legal Brief (Law School)<br />

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES<br />

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION<br />

QUESTION PRESENTED<br />

STANDARD OF REVIEW<br />

STATEMENT OF THE CASE<br />

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT<br />

ARGUMENT<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

Motion <strong>to</strong> Quash<br />

Legal Negotiation Exercise Reflection Paper 2: The Negotiation – Clients (Law School)<br />

Adverse Possession

I am more than my LSAT Scores (Law School Application)<br />

Describe Your Background (<strong>College</strong> Application)<br />

Personal Statement (Law School)<br />

My Career as a Computer Security Expert (Job Application)<br />

Business School Application<br />

How I Benefited from this Course (Sociology)<br />

Personal Statement (Law School Application)<br />

Supplementary Essay (Law School Application)<br />

The American Dream (<strong>College</strong> Application)<br />

Geico Job Application (Application Essay)<br />

Personal Statement (Law School Application)<br />

The Crypts Beneath Rome (<strong>College</strong> GenEd)<br />

Breaching Patriarchal Throwness with a Hatpin (Feminist Theory/Politics)<br />

A Feminist Breaching Experiment<br />

Cornell West on Malcolm X (Politics)<br />

Fork etiquette (Anthropology)<br />

McClatchey on Race and IQ (Current Events)<br />

Freedom of Speech: Its Scope and Limits (Politics)<br />

Defending Freedom of Speech (Ethics/Politics)<br />

Shutter Island: A Social Scientist’s Perspective (Social Science/Media Studies)<br />

The Sad Case of Richard Cory: Analysis of a Poem (Literary Analysis)<br />

Why <strong>College</strong> Admissions Should Continue <strong>to</strong> be Based at least in<br />

part on Standardized Test Scores (Public Policy)<br />

Being a Voter in Texas (Current Events)<br />

Three Takeaways from The Young Turks’ ‘Iceland does the Unimaginable’ (Current Events)<br />

The Works of Modern Art (Art His<strong>to</strong>ry)<br />

Divan Japonais<br />

A Paradigm of the Art Nouveau Movement<br />

New Statendam<br />

Analysis of a piece of an Art Deco Work<br />

Lawn Tennis<br />

Analysis of a piece of an Art Deco Work<br />

Student-passage and my revision thereof (Pedagogy)<br />

Summary and Analysis of Toma<strong>to</strong>land (Politics/Current Events)<br />

A Demographic Analysis of Dropout-likelihood and Dropout-rationality<br />

List of Figures<br />

Chapter 1: Introduction <strong>to</strong> the Study<br />

Introduction<br />

Background of the Study<br />

Problem Statement<br />

Purpose of the Study<br />

Research Questions and/or Hypotheses<br />

Advancing Scientific Knowledge and Significance of the Study<br />

Rationale for Methodology<br />

Nature of the Research Design of the Study<br />

Definitions of Terms<br />

Assumptions, Limitations, Delimitations<br />

Summary and Organization of the Remainder of the Study

Chapter 2: Literature Review<br />

Introduction <strong>to</strong> the Chapter<br />

Identification of the Gap<br />

Identification of the Gap (Continued): The Statistical Data<br />

Theoretical Foundations and/or Conceptual Framework<br />

Review of the Literature<br />

Literature Review: Vocational Careers<br />

Literature Review: Earnings on the Part of Non-vocationally trained Non-graduates<br />

Literature Review: Financial Costs and Benefits of Low IQ Degree<br />

Summary<br />

Chapter 3 Methodology<br />

Introduction<br />

Statement of the Problem<br />

Research Questions and Hypotheses<br />

Research Methodology<br />

Research Design<br />

Population and Sample Selection<br />

Instrumentation<br />

Validity<br />

Reliability<br />

Data Collection and Management<br />

Data Analysis Procedures<br />

Ethical Considerations<br />

Limitations and Delimitations<br />

Summary<br />

Is the Turing Test a good test of intelligence? (philosophy)<br />

Is the Turing Test a good test of intelligence? Second Version (philosophy)<br />

Should Caffeine be a Controlled Substance?<br />

Who started the Cold War?<br />

Who was a better President? Eisenhower or JFK?<br />

Who was a better President? Nixon or LBJ?<br />

Technology-caused Job-shortages and the Need for Universal Welfare<br />

My Reaction <strong>to</strong> Schoenberg’s A Survivor from<br />

Warsaw https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DFXkc9AGoeU<br />

Statistics: Basic Principles and Theorems (Math/Statistics)<br />

Poem and Song Compared: To His Coy Mistress Compared with Don’t Be Cruel (Literary Analysis)<br />

Random Variables, Discrete Variables, Continuous Variables (Math/Statistics)<br />

Statistics Exam Prep Sheet<br />

Concert Report (Music/Musicology)<br />

Statistics Final Exam Review Sheet (Math/Statistics)<br />

Music Journal (Music/Musicology)<br />

References<br />

Appendix A.<br />

Ideas as Networks: Reflecting on Steven Johnson’s<br />

“Where Good Ideas Come From”<br />

Are we born good? Response <strong>to</strong>: “Born Good?” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FRvVFW85IcU)<br />

An Exercise in Legal Interpretation<br />

Posts for Business Ethics Class

Can you think of an example where someone has been honest but not ethical, as Carter (assigned<br />

reading) says?<br />

What was your decision in "Desperate Air?" Sell? Not sell? Why?<br />

How far would YOU have gone in the obedience experiment?<br />

Reactions <strong>to</strong> the Jones Day report on the rankings scandal at the Fox School<br />

Can you apply ideas from the Bazerman and Tenbrunsel article <strong>to</strong> McCoy's dilemma in the Parable of the<br />

Sadhu?<br />

Will it be possible for you <strong>to</strong> maintain your ethical values yet succeed in the business world?<br />

Have you ever been in the "Endgame" scenario?<br />

What is your "home base" ethical theory? (from the Deckop chapter)<br />

Is THE social responsibility of business <strong>to</strong> increase its profits? -- Who's right: Friedman or Mackey?<br />

Were WalMart <strong>to</strong> increase its pay and benefit level <strong>to</strong> those of Costco (S<strong>to</strong>ne article) or TJ's (Wilke<br />

article), or LaColumbe (Carmichael article) would it be more or less financially successful?<br />

Have you ever had a "Sadhu" dropped at your feet (so <strong>to</strong> speak). If so, what did you do?<br />

Do you think corporations are living up <strong>to</strong> their original purpose in society?<br />

Identify an argument in an article, book etc. that does poorly on TWO or more of the 7 standards Paul &<br />

Elder say help assess critical thinking. Briefly discuss.<br />

Response <strong>to</strong> Posts about Descartes’ Evil Demon (my material in italics)<br />

Economics Quiz on Elasticity<br />

Summary of Video about Milgram Experiment https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f97VYdkHZK8<br />

Racism and Sexism<br />

Answers <strong>to</strong> (somebody else’s) Questions about Orwell’s “Shooting and Elephant” (My content in italics)<br />

When is it a good for a company <strong>to</strong> decentralize?<br />

A Tough Business Decision<br />

An Ethical Quandry<br />

Legitimate Line Extensions as an Alternative <strong>to</strong> Front-businesses<br />

The Solution <strong>to</strong> the Pizza Puzzle<br />

Why is Sartre’s later work so bad? Response <strong>to</strong> “Human all <strong>to</strong>o human: Sartre”<br />

(http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4G4R_iAZWbQ)<br />

Summary and Analysis of The Yellow Wallpaper<br />

Summary and Analysis of James Baldwin’s Sonny’s Blues<br />

Dialogue about Sonny’s Blues and The Yellow Wallpaper<br />

The Purpose of Fiction<br />

Summaries with Analysis of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House and Hawthorn’s Young Goodman Brown<br />

BCG Matrix Bulletin Points<br />

Accounting Cheat Sheet<br />

Dennett and Skinner on the Human Condition<br />

Response <strong>to</strong> “Reading Minds” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8jc8URRxPIg) and<br />

“Neuroscience and Free Will” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VnGDrc_s6KA)<br />

Do we have free will? Response <strong>to</strong> “Operant Conditioning”<br />

(http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I_ctJqjlrHA)<br />

“Consciousness and Free Will” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PyWfVyoz7BQ)<br />

The Sociology of Epistemology<br />

Cartesian Skepticism<br />

Response <strong>to</strong> (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QE8dL1SweCw)<br />

What do I know with certainty?<br />

Response <strong>to</strong> http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ouk936EtkMc<br />

Internal vs. External Motiva<strong>to</strong>rs

Reflections on Dan Pink’s Ted Talk (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rrkrvAUbU9Y)<br />

Judith Ortiz Cofer’s “American His<strong>to</strong>ry” and the Evils of Prejudice<br />

Why was Socrates put <strong>to</strong> death? Response <strong>to</strong> (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zE7PKRjrid4)<br />

“The Trial of Socrates” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=380KSdkV6zY)<br />

The Problem of the One and the Many<br />

Response <strong>to</strong> : “The Pre-Socratics: Part 1” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=83kUMEjaCUA)<br />

“The Pre-Socratics: Part 2” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_IRy3E-BZhY)<br />

“The Pre-Socratics: Part 3” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qVrwRHSIRIg)<br />

What do we have that chimps don’t? Response <strong>to</strong> : “Ape Genius”<br />

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wg-mPjhCnc8)<br />

My Questions about “Dum Dum Boys”, by Cameron Joy, pp. 109-119<br />

The Meaning of Pla<strong>to</strong>’s Cave Allegory<br />

Response <strong>to</strong> (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=69F7GhASOdM)<br />

An Ethical Dilemma<br />

Answers <strong>to</strong> questions about documentary about how corporations are evil (Response <strong>to</strong><br />

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pin8fbdGV9Y)<br />

Answers <strong>to</strong> questions about documentary about the<br />

the Parable of the Sadhu (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nxXZEnR_JSM)<br />

Answers <strong>to</strong> Questions about Walmart-documentary (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jf-Sr3SjBzk)<br />

Advertising Assignment<br />

Does good employee treatment (SAS movie) usually mean more profit? If not, why not? If so, why, and<br />

why don't more companies treat their employees well?<br />

Should corporate executives be held criminally liable for deaths or injuries in the workplace? Discussion<br />

Post<br />

Is Money a Drug? Discussion Post<br />

The “Heaven Help Her” Scenario: Utilitarian and Universalist Perspectives<br />

Classification of Retailers<br />

Lewin Change Model<br />

Fac<strong>to</strong>rs that drive change<br />

The Strategic Planning Process<br />

Critical thinking traps<br />

Do we have free will? Responses <strong>to</strong> discussions posts (my content in bold-faced italics)<br />

Discussion Post #8 (worth 30 points; at least 200 words): Due by Saturday, Oct 26th, by 11:30 p.m. (my<br />

work in boldfaced italics)<br />

Summary and Analysis of The Yellow Wallpaper<br />

Dialogue about Sonny’s Blues and The Yellow Wallpaper<br />

Discussion Post #8<br />

Legal vs. Substantive Freedom and the Paradox of the Free Market<br />

Reflections on works by Hall, Debord, and Morgan & Tierney<br />

QUANTITATIVE Dissertation Research Plan<br />

Discussion Post #8 (worth 30 points; at least 200 words): Due by Saturday, Oct 26th, by 11:30 p.m.<br />

Discussion Post on the Statement “‘Whatever happens is meant <strong>to</strong> be” (my content in boldfaced italics)<br />

Whatever happens<br />

Is Everything Meant <strong>to</strong> be?<br />

Literature Discussion Post 9 Discussion Post # 9

Introduction<br />

The McFadden Act: Its Nature and Consequences<br />

The McFadden Act of 1927 gave so-called ‘national banks’ more power than they<br />

previously had, while limiting the power of so-called ‘state banks’ (Rajan et al., 2015). We must<br />

define the terms ‘national bank’ and ‘state bank’ before we can say more precisely what the<br />

McFadden Act did or what its ramifications were, and we must also make a few points of a<br />

general nature about the Federal Reserve System.<br />

A ‘state bank’ is one that is chartered by a given state and is subject <strong>to</strong> that state’s<br />

banking laws. By contrast, a ‘national bank’ is one that is part of the Federal Reserve System<br />

(Dou et al., 2015). Consequently, a ‘national bank’ need not have branches in more than one<br />

state. In fact, as we will presently discuss, the McFadden Act expressly prohibited banks,<br />

whether national or not, from having branches in more than one state (West <strong>2019</strong>).<br />

National banks function as an organized network—known as the Federal Reserve<br />

System---that ensures that any given one of its members always fulfills its fiduciary<br />

responsibilities <strong>to</strong> its cus<strong>to</strong>mers. This means that a given national bank is always able <strong>to</strong> let its<br />

cus<strong>to</strong>mers withdraw funds, even if there is a run on the bank (West <strong>2019</strong>). This in turn means<br />

that members of the Federal Reserve System loan one another money and do so knowing that<br />

they will be repaid. Consequently, national banks have <strong>to</strong> comply with an extremely strict set of<br />

guidelines that guarantee that they are always in a position <strong>to</strong> honor their commitments both <strong>to</strong><br />

their own cus<strong>to</strong>mers and <strong>to</strong> other national banks (Flannery et al., 2017).<br />

National banks therefore have both individuals as well as other banks for their clients,<br />

and the likelihood that a given national bank will default on its obligations is virtually nil. By<br />

contrast, state banks do not service other banks; they only service individuals. Moreover, state

anks can and sometimes do fail, leaving their credi<strong>to</strong>rs and deposi<strong>to</strong>rs in the lurch. This means<br />

that in some respects state banks have more discretion than national banks when it comes making<br />

loans or investments, and this means that national banks may be less able than state banks <strong>to</strong><br />

capitalize on risky but potentially lucrative opportunities. The other side of the coin is that state<br />

banks can fail, since they have no guarantee of an emergency bailout, whereas national banks<br />

cannot fail, since they do have such a guarantee (West <strong>2019</strong>).<br />

His<strong>to</strong>rical Backs<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

The Federal Reserve System was created in 1913 for the express purpose of providing the<br />

public with banks that would never fail. During the first 14 years of its existence, it seemed <strong>to</strong><br />

function very well and had a great deal of credibility, with both the financial sec<strong>to</strong>r and the<br />

general public (Bernanke 2017). At the same time, national banks began <strong>to</strong> resent being so much<br />

more strictly regulated than state banks, since it meant that national banks had <strong>to</strong> forego<br />

opportunities from which state banks could profit (Bernanke 2017). They consequently lobbied<br />

Congress <strong>to</strong> loosen some of these regulations; and they were successful, thanks largely <strong>to</strong> the<br />

public’s high level of trust in them, the result being the McFadden Act, the main provisions of<br />

which are as follows:<br />

(1) National banks had their charters renewed ahead of schedule. (They were not due for<br />

renewal until 1933.)<br />

(2) National banks were allowed <strong>to</strong> open branches in any state where state banks were<br />

allowed <strong>to</strong> have branches.

(3) National banks were allowed <strong>to</strong> engage in previously off-limits investing activities,<br />

including buying real estate and purchasing subsidiaries.<br />

(4) Both state and national banks were prohibited from having branches in more than one<br />

state.<br />

Provisions (1)-(3) gave national banks more power than they previously had, and<br />

provision (4) prevented state banks from becoming multi-state entities in an effort <strong>to</strong> regain their<br />

lost competitive advantage (Conti-Brown 2017).<br />

From McFadden <strong>to</strong> Riegle-Neal<br />

There were two sides <strong>to</strong> the McFadden Act, in that it gave national banks powers that<br />

they previously didn’t have, while subjecting all banks, including national banks, <strong>to</strong> severe<br />

restrictions, the most obvious one being the prohibition on having branches in multiple states.<br />

These two aspects of the McFadden Act reflect the public’s ambivalence at that time <strong>to</strong>wards<br />

banks (Rajan et al., 2015). On the one hand, the public was distrustful of banks and wished <strong>to</strong><br />

prevent the emergence of a banking monopoly or oligopoly: hence the fourth provision. On the<br />

other hand, the country was prospering, and the public believed the Federal Reserve System <strong>to</strong><br />

be at least partly responsible for this: hence the first three provisions (Bernanke 2017).<br />

According <strong>to</strong> some experts, the extra powers now had by national banks led <strong>to</strong> reckless<br />

behavior on their part that helped bring about the Crash of 1929. Whether or not this is true, the<br />

bill that led <strong>to</strong> the McFadden Act almost certainly would not have passed had Congress voted on<br />

it right after the 1929 Crash, instead of right before it (West <strong>2019</strong>).

In the ensuing decades, national banks circumvented the prohibition on interstate banking<br />

by buying controlling interests in banks in other states. This practice came <strong>to</strong> a halt in 1956 with<br />

the enactment of the Douglass Amendment of the Bank Holding Act. This amendment explicitly<br />

prohibited a bank in a given state from buying a controlling interest in an out-of-state bank<br />

except in cases where the laws of both states permitted it <strong>to</strong> be done. With this workaround shut<br />

down, national banks were simply unable <strong>to</strong> have multi-state markets, which in at least some<br />

cases obstructed the flow of investment capital <strong>to</strong> places where it was most needed (Epstein<br />

<strong>2019</strong>).<br />

In the mid-1970s banks from other countries started <strong>to</strong> become a major economic<br />

presence in the United States (Bernanke 2017). Such banks were not subject <strong>to</strong> the McFadden<br />

Act and were able <strong>to</strong> form branches in multiple states. This led <strong>to</strong> outrage on the part of<br />

American Banks, which led <strong>to</strong> legislation prohibiting foreign banks from forming branches in<br />

multiple states and, more importantly, led Congress <strong>to</strong> ask President Jimmy Carter <strong>to</strong> examine<br />

the banking system, the feeling being that McFadden and other similar regulations were<br />

preventing American banking from being able <strong>to</strong> compete in an increasingly global and dynamic<br />

financial environment. Carter did not himself do anything about this; nor did his successor<br />

Ronald Reagan. But legisla<strong>to</strong>rs were now very conscious of the possibility that problems with<br />

the financial sec<strong>to</strong>r were causing problems for the American economy as a whole (Epstein <strong>2019</strong>).<br />

In 1991 and 1992, laws were passed that gave national banks some latitude in the way of<br />

forming cooperative arrangements with banks in other states. But these various acts all left<br />

McFadden very much intact, and there was a growing consensus that, thanks <strong>to</strong> McFadden,<br />

American banking was a hyper-inefficient anachronism. In particular, Sena<strong>to</strong>r Donald Riegle<br />

(Michigan) and Congressmen Stephen Neal (North Carolina) urged the removal of McFadden’s

an on interstate banking, which they saw as responsible for the economic problems suffered by<br />

their respective constituencies. Finally, in 1994, the Riegle-Neal Act was passed, and banks were<br />

no longer prohibited from operating in multiple states (Epstein <strong>2019</strong>).<br />

Analysis<br />

In this context, two questions arise: How did McFadden affect Banks? And how did it<br />

affect the economy as a whole? It may well be that McFadden made banking less profitable than<br />

it would otherwise be, but that by itself gives us no information as <strong>to</strong> how McFadden affected the<br />

economy as a whole? So what was that effect? And what about Riegle-Neal? What were the<br />

macroeconomic consequences of these acts?<br />

Judging by the USA’s GDP over the last 100 years, the answer seems <strong>to</strong> be---none.<br />

Figure 1 American GDP 1929-2011<br />

Fernald, J., & Li, H. (<strong>2019</strong>). Is slow still the new normal for GDP growth?. FRBSF Economic<br />

Letter, 17.<br />

During the last century, American macroeconomic growth has been steady. There have<br />

been a few dips and a few spikes---but nothing that can be correlated either with McFadden or<br />

with Riegle-Neal. Those who lobbied for the removal of McFadden put forth the usual

arguments about the deep macroeconomic significance of ‘readily available credit’—the idea<br />

being that economies grind <strong>to</strong> a halt when loans cannot be made sufficiently quickly or<br />

abundantly (Fernald et al., <strong>2019</strong>). And there is no denying that borrowing and lending are<br />

necessary for macroeconomic health, simply because the people who recognize economic<br />

opportunities are unlikely <strong>to</strong> have the vast amounts of money needed <strong>to</strong> capitalize on them<br />

(Sowell 2017).<br />

That said, McFadden did not prevent individuals and companies from getting loans. What<br />

it did was <strong>to</strong> restrict what a given bank could do in the way of servicing a given person’s need for<br />

a loan. Under McFadden, a bank in Wyoming would not be able <strong>to</strong> loan money <strong>to</strong> someone in<br />

Utah; but that person could still get a loan—from a Utah bank (Bernanke 2017).<br />

It will be said that, under those circumstances, Utah banks won’t have <strong>to</strong> compete as hard<br />

for that person’s business and won’t do as good a job as they would if they had <strong>to</strong> compete with<br />

banks in other states (Sowell 2017). And maybe that is true. But if it is, there is no evidence of it.<br />

During the supposedly dark McFadden years, American companies were being founded, taken<br />

public, merged with, acquired, and sold at a rate unprecedented in human his<strong>to</strong>ry (Angilella et<br />

al., <strong>2019</strong>).<br />

Figure 2 Down Jones Industrial Average 1900-2012

Angilella, S., & Morelli, D. (<strong>2019</strong>). Are the s<strong>to</strong>ck prices influenced by the publication of<br />

the annual financial statements? Evidence from the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Operational<br />

Research, 1-10.<br />

To be sure, this growth did not s<strong>to</strong>p with Riegle-Neal. There is in fact no clear evidence<br />

that Riegle-Neal has slowed down economic growth. McFadden put limits on bank profits, and<br />

Riegle-Neal removed those limits, but there is otherwise little evidence that either one was of any<br />

real consequence. This is subject only <strong>to</strong> the qualification that by deregulating the credit market,<br />

Riegle-Neal and other deregula<strong>to</strong>ry measures might possibly have had a hand in the housing<br />

bubble responsible for the 2007-2010 recession (Conti-Brown 2017).<br />

Figure 3<br />

Figure 3 is identical with the curve in Figure 1. Is there anything about the shape of<br />

Figure 3 that indicates a change in banking regulations? The suggestive dimple near the end did<br />

not happen in the aftermath of any such changes, and no such changes happened in its aftermath.<br />

If we try <strong>to</strong> correlate GDP with specific banking regulations, we have little success. But<br />

when we compare al<strong>to</strong>gether different financial systems, the results are striking:

Figure 3 USA GDP vs. USSR GDP 1917-1990<br />

Guriev, S. (<strong>2019</strong>). Gorbachev versus Deng: A Review of Chris Miller's The Struggle <strong>to</strong><br />

Save the Soviet Economy. Journal of Economic Literature, 57(1), 120-46.<br />

What all of this suggests is that banking regulations appear <strong>to</strong> have more of an effect on<br />

banks than they do on the economy as a whole, with the possible qualification that a complete<br />

absence of regulation can lead <strong>to</strong> credit bubbles and brief subsequent dips. Advocates of Riegle-<br />

Neal would have us believe that McFadden was sapping the economy’s strength. But there is<br />

literally no evidence of this at all. Whatever effects McFadden and Riegle-Neal had, it is not<br />

clear what they are or what their significance is.<br />

References<br />

Angilella, S., & Morelli, D. (<strong>2019</strong>). Are the s<strong>to</strong>ck prices influenced by the publication of<br />

the annual financial statements? Evidence from the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Operational<br />

Research, 1-10.<br />

Bernanke, B. S. (2017). Federal reserve policy in an international context. IMF Economic<br />

Review, 65(1), 1-32.

Conti-Brown, P. (2017). The power and independence of the Federal Reserve. Prince<strong>to</strong>n<br />

University Press.<br />

Dou, Y., Ryan, S. G., & Zou, Y. (2018). The Effect of Credit Competition on Banks’<br />

Loan-Loss Provisions. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 53(3), 1195-1226.<br />

Epstein, G. (<strong>2019</strong>). Domestic stagflation and monetary policy: The Federal Reserve and<br />

the Hidden Election. Chapters, 2-56.<br />

Fernald, J., & Li, H. (<strong>2019</strong>). Is slow still the new normal for GDP growth?. FRBSF Economic<br />

Letter, 17.<br />

Flannery, M., Hirtle, B., & Kovner, A. (2017). Evaluating the information in the federal<br />

reserve stress tests. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 29, 1-18.<br />

Guriev, S. (<strong>2019</strong>). Gorbachev versus Deng: A Review of Chris Miller's The Struggle <strong>to</strong><br />

Save the Soviet Economy. Journal of Economic Literature, 57(1), 120-46.<br />

Pres<strong>to</strong>n, H. H. (1927). The McFadden banking act. The American Economic<br />

Review, 17(2), 201-218.

Rajan, R. G., & Ramcharan, R. (2015). Constituencies and legislation: the fight over the<br />

McFadden Act of 1927. Management Science, 62(7), 1843-1859.<br />

Press.<br />

Sowell, T. (2017). Education: Assumptions versus his<strong>to</strong>ry: Collected papers. Hoover<br />

West, R. C. (<strong>2019</strong>). Banking reform and the Federal Reserve, 1863-1923. Cornell<br />

University Press.<br />

Hahn and Tols<strong>to</strong>y and Disillusionment and Maturation: A Comparison of Kimiko Hahn’s In<br />

Childhood and Tols<strong>to</strong>y’s The Death of Ivan Ilych<br />

Hahn’s poem In Childhood (2003) is about disillusionment. We grow up<br />

believing in fairy tales---the primary one being that there is no such thing as death---<br />

and we come <strong>to</strong> realize that those fairy tales are just that. We grow up believing that<br />

our beloved dog ‘went <strong>to</strong> a better place’ and is residing happily in ‘dog heaven’, when,<br />

in actuality, he is simply gone.<br />

things don't die or remain damaged<br />

but return: stumps grow back hands,<br />

a head reconnects <strong>to</strong> a neck,<br />

a whole corpse rises blushing and newly elastic.<br />

Later this vision is not True:

the grandmother remains dead<br />

not hibernating in a wolf's belly.<br />

Or the blue parakeet does not return<br />

Lines 1-4 refer <strong>to</strong> the child’s belief that loved ones don’t die. Things don’t<br />

vanish; they merely go in<strong>to</strong> hiding. Limbs may ‘go away’, but they grow back, with the<br />

qualification that ‘limbs’ refer <strong>to</strong> any valuable extension of oneself—a relative, a pet,<br />

or, indeed, an actual limb. Lines 5-8 are <strong>to</strong> the effect that this is indeed an infantile<br />

fallacy. The truth is---the parakeet did die, and so did grandma. They didn’t ‘move out’<br />

or ‘go <strong>to</strong> a better place.’ They are gone, and that’s the cold hard truth of the matter, this<br />

being the whole point of the poem:<br />

Or the blue parakeet does not return<br />

from the little grave in the fern garden<br />

The point being that the bird is not ‘with grandmother.’ They were here; now<br />

they’re not; and that’s the end of the matter.<br />

But we can’t accept these cold, hard truths, so we rationalize:<br />

though one may wake in the morning<br />

thinking mother's call is the bird.<br />

Or maybe the bird is with grandmother

inside light.<br />

In other words, we tell more fairy tales <strong>to</strong> ourselves, rather than simply part with<br />

our delusions:<br />

Or grandmother was the bird<br />

and is now the dog<br />

gnawing on the chair leg.<br />

The point being that they are not all in ‘doggy heaven’ waiting for us, try as we<br />

might <strong>to</strong> believe otherwise.<br />

Of course, one’s belief that one’s loved ones don’t die is but one embodiment of<br />

an entire network of childish delusions. We grow up believing that the world is<br />

governed by moral laws—that justice is a force in much the same way as gravity. Most<br />

of us never part with this belief, at least not entirely. Even the most jaded criminal is<br />

surprised when one of his cohorts testifies against him or when the prosecuting<br />

at<strong>to</strong>rney renegs on a plea deal. Even s<strong>to</strong>ne psychopaths are genuinely shocked when<br />

they are on the receiving end of psychopathic conduct, showing how deeply ingrained<br />

our presumptions are as <strong>to</strong> the supposed ‘moral structure’ of the universe.<br />

Relatedly, even the most clear-sighted people never cease <strong>to</strong> idealize others. A<br />

husband does not want <strong>to</strong> believe that his beloved wife is cut from the same cloth as

himself---that she has lusts and weaknesses much as he does. Even hatred of another<br />

involves a certain idealization of them: we see the object of our hatred as a villain who<br />

knows exactly what he is doing, when in truth he is a weak person who is acting out of<br />

fear and confusion. And our hatred of people is often borne of betrayal, this being why<br />

former friends are often the objects of the most<br />

If we saw people as they are, instead of seeing them through the lens of our<br />

idealizations, we would neither love nor hate them; and so long as we do have<br />

emotional attachments <strong>to</strong> them, we do not see them for what they are. More generally,<br />

so long as we relate <strong>to</strong> the world in an emotion- as opposed <strong>to</strong> reason-based manner,<br />

we understand it in terms of fairy tales and therefore do not see it as it is. As we age,<br />

the fairy tales in question change form: the five-year-old boy believes that he is<br />

Superman, whereas his 35-year-old counterpart believes that he will be the next Bill<br />

Gates, but neither is any less deluded than the other.<br />

These principles are not specific <strong>to</strong> any culture or era. They hold universally.<br />

They are hold neither more nor less of the United States <strong>to</strong>day than they did of Sumer<br />

or Sparta---or, indeed, than they did of Russian in the late 19 th century, this being the<br />

setting of Tols<strong>to</strong>y’s The Death of Ivan Ilych, which, like Hahn’s In Childhood, is about<br />

parting with infantile illusions. The difference is that Ivan Ilych is about the<br />

rationalizations that adults use <strong>to</strong> cloak their continued acceptance of fairy tales,<br />

whereas Hahn’s poem is much less concerned with those rationalizations than with the<br />

child’s naïve and uncritical acceptance of those fairy tales themselves.

The fairy tale that Tols<strong>to</strong>y work targets is the idea that we if we do what is<br />

‘expected’ of us, then our lives will be good—as though social acceptance had the<br />

power <strong>to</strong> contravene psychological and biological reality. ‘Others may like us and even<br />

give us awards,’ Tols<strong>to</strong>y’s s<strong>to</strong>ry tells us, ‘but what does it matter if one is physically ill<br />

and in pain?’ Ivan Ilych was in pain and his health was gone; what good did his<br />

distinctions do him then? This is the point of the passage where Tols<strong>to</strong>y speaks<br />

admiringly of Gerasim, the simple<strong>to</strong>n who caretakes him in his dying days. “It’s God’s<br />

will”, Gerasim says:<br />

“We shall all come <strong>to</strong> it some day”, said Gerasim, displaying his teeth---the<br />

even white teeth of a healthy peasant---and, like a man in the thick of urgent work, he<br />

briskly opened the front door, called the coachman, helped [Ilych] in<strong>to</strong> the sledge, and<br />

sprang back <strong>to</strong> the porch as if in readiness for what he had <strong>to</strong> do next. Peter Ivánovich<br />

found the fresh air particularly pleasant after the smell of incense, the dead body, and<br />

carbolic acid. 1<br />

Gerasim has health and vigor; these things are real. Ilych has wealth and titles;<br />

these things are not. And Ilych’s life was based on the fairy tale that these unrealities<br />

could function as surrogates for the realities they displaced—the point of Tols<strong>to</strong>y’s<br />

1<br />

Abcarian, Richard; Klotz, Marvin; Cohen, Samuel. Literature: The Human<br />

Experience, Shorter Edition (p. 806). Bedford/St. Martin's. Kindle Edition.

novella being that they cannot. At the end of the day, life is life and death is death; a<br />

loveless marriage <strong>to</strong> a ‘respectable’ woman is still a loveless marriage, and a happy<br />

marriage <strong>to</strong> a woman of ill repute is still a happy marriage. What is real is real; and<br />

what isn’t, isn’t.<br />

Ivan Ilych is about the fairy tales that adults accept, long after they have parted<br />

with the fairy tales about deceased pets and the like. Another difference between these<br />

two works is that Ivan Ilych is about our losing souls by clinging <strong>to</strong> fairy tales about<br />

status and other unrealities, whereas In Childhood is simply about disillusionment.<br />

An even more striking difference is that whereas Hahn represents children as<br />

simply being deluded, Tols<strong>to</strong>y represents children as being less delusive than adults.<br />

When Ilych is about <strong>to</strong> die, he realizes that he hasn’t been happy since childhood, and<br />

considerations of social status were conspicuously absent from those experiences. “the<br />

further back in life he looked,” Ilych recalls, “the more good there was in it”, his life<br />

having becoming more and more drained of meaning as he got caught in an absurd maze<br />

of titles and distinctions and poses. 2<br />

Of course, both authors are right. Children are capable of being ‘real’ in a way<br />

that is impossible for world-weary adults. At the same time, children do a very<br />

car<strong>to</strong>onish conception of the world, believing it <strong>to</strong> be inhabited by the likes of Bugs<br />

Bunny and Elmer Fudd, whereas adults, for all their faults, including their many<br />

delusions, do not have comparably deep-seated misconceptions as <strong>to</strong> the nature of<br />

2<br />

Abcarian, Richard; Klotz, Marvin; Cohen, Samuel. Literature: The Human<br />

Experience, Shorter Edition (p. 838). Bedford/St. Martin's. Kindle Edition.

eality. At the same time, each author has articulated a way in which maturation involves<br />

the shedding of delusions, with the qualification that Hahn is concerned with transition<br />

–made by all human beings---from childhood <strong>to</strong> adolescence, whereas Tols<strong>to</strong>y is<br />

concerned with the transition---not made in most cases—from garden-variety adulthood,<br />

with its excessive regard for hollow social norms, <strong>to</strong> a state of veritable enlightenment.<br />

Critical Viewing Form: SAS

Instructions: Please address each item below for each movie. The <strong>to</strong>tal length of your critical viewing<br />

form responses should be approximately one-half <strong>to</strong> one page, single spaced. This form will be graded<br />

on a pass/fail basis. To pass, you need <strong>to</strong> provide reasonably detailed and insightful answers <strong>to</strong> the<br />

items below.<br />

1. Briefly summarize the basic plot, or issue that the movie addresses.<br />

This documentary concerned SAS, a North Carolina based software company that treats its employees<br />

phenomenally well and is also profitable. (‘SAS’ is short for ‘statistical analysis software’, this being the<br />

company’s signature product.)<br />

2. What do you think is the most interesting point in the movie?<br />

The attention <strong>to</strong> details, relating <strong>to</strong> employee welfare, e.g. the massages and M&M’s.<br />

3. What is the most controversial statement you’ve heard?<br />

The statement, made by the reporter, that people would be ‘shocked’ by the company’s positive ethos.<br />

This struck me as controversial precisely because it’s true, which shows how thoroughly the public has<br />

internalized the misguided notion that workers should be brutalized.<br />

4. What is the most important ethical issue that the movie is addressing? Please explain.<br />

That decency <strong>to</strong> one’s employees and colleagues is confluent with economic self-interest—a<br />

lesson I know from my own case. I run a small firm and, although I am the boss, I never<br />

issue orders and always treat everyone—clients and colleagues---utterly decently, simply<br />

because an unhappy employee, I found, can cause trouble and a happy one will go above<br />

and beyond the call of duty.<br />

Critical Viewing Form: McWane Inc.<br />

Instructions: Please address each item below for each movie. The <strong>to</strong>tal length of your critical viewing<br />

form responses should be approximately one-half <strong>to</strong> one page, single spaced. This form will be graded<br />

on a pass/fail basis. To pass, you need <strong>to</strong> provide reasonably detailed and insightful answers <strong>to</strong> the<br />

items below.<br />

1. Briefly summarize the basic plot, or issue that the movie addresses.<br />

This is the follow-up <strong>to</strong> a 2003 exposé, conducted by Frontline, of McWane Inc., the upshot being that<br />

McWane’s ownership and management were criminally negligent, with conditions in their plants being<br />

<strong>to</strong>tally inhumane, leading <strong>to</strong> routine worker-injuries, including burns and amputations, and death. In the<br />

intervening years, many senior staff went <strong>to</strong> jail, and the new management (or what was left of the old<br />

one) changed McWane for the better, seeing <strong>to</strong> it that the requisite safety guidelines were complied.

2. What do you think is the most interesting point in the movie?<br />

That McWane blamed worker-injuries on worker-incompetence, which I found <strong>to</strong> be utterly despicable.<br />

3. What is the most controversial statement you’ve heard?<br />

That even though nine workers died because of McWane’s criminal negligence, McWane was only tried<br />

for one of the deaths and, when found guilty, was given a misdemeanor conviction—less than what a<br />

drunk driver would receive.<br />

4. What is the most important ethical issue that the movie is addressing? Please explain.<br />

That heavy industry has <strong>to</strong> be moni<strong>to</strong>red, since, left <strong>to</strong> its own devices, it will treat its labor as so much<br />

chattel, not only <strong>to</strong> their detriment but <strong>to</strong> that of the moral fiber of society as a whole. I was heartened<br />

that, owing <strong>to</strong> the prequel <strong>to</strong> this documentary, McWane had changed its ways and also that many<br />

regula<strong>to</strong>ry and legal changes had been made; but I was dismayed that some of the principal laws<br />

relating <strong>to</strong> worker safety have not been changed, showing that, owing corporate lobbying, adequate<br />

oversight of industrial giants is not always forthcoming.<br />

Critical Viewing Form: Theranos<br />

Instructions: Please address each item below for each movie. The <strong>to</strong>tal length of your critical viewing<br />

form responses should be approximately one-half <strong>to</strong> one page, single spaced. This form will be graded<br />

on a pass/fail basis. To pass, you need <strong>to</strong> provide reasonably detailed and insightful answers <strong>to</strong> the<br />

items below.<br />

1. Briefly summarize the basic plot, or issue that the movie addresses.<br />

A young and seemingly brilliant woman, Elizabeth Holmes started Theranos, a bio-tech company, and<br />

raised billions from wide-eyed inves<strong>to</strong>rs, having convinced the world that she was the next Steve Jobs.<br />

But the product (a medicine delivery system) turned out not <strong>to</strong> work, as Holmes knew all along, as it<br />

turned out, and she was just a con-woman all along.<br />

2. What do you think is the most interesting point in the movie?<br />

That Holmes was able <strong>to</strong> change the timbre and pitch of her voice <strong>to</strong> suit her immediate business needs.<br />

3. What is the most controversial statement you’ve heard?<br />

That Holmes was an unusually convincing con-woman.<br />

This statement is true by the obviously metrics, given that she lied her way <strong>to</strong> billions.<br />

But when I saw and listened <strong>to</strong> her, I was struck by how unoriginal she was as a con-artist, with her<br />

crocodile fake tears and well-worn sales pitch about ‘never having <strong>to</strong> say goodbye <strong>to</strong>o soon.’

4. What is the most important ethical issue that the movie is addressing? Please explain.<br />

That the public, including inves<strong>to</strong>rs, should be more wary of fraudsters and not expect someone not <strong>to</strong><br />

be a fraudster simply because they are young and good looking. Investments, including investments of<br />

trust, should be based on results, not appearances.<br />

Critical Viewing Form: Enron<br />

Instructions: Please address each item below for each movie. The <strong>to</strong>tal length of your critical viewing<br />

form responses should be approximately one-half <strong>to</strong> one page, single spaced. This form will be graded<br />

on a pass/fail basis. To pass, you need <strong>to</strong> provide reasonably detailed and insightful answers <strong>to</strong> the<br />

items below.<br />

1. Briefly summarize the basic plot, or issue that the movie addresses.<br />

The movie documents the rise and extremely corrupt fall of Enron. Enron started out as a legitimate<br />

energy-company and then invested heavily in a number of concerns that went belly up. Instead of<br />

copping <strong>to</strong> its mistake, it cooked the books, with the assistance of accounting giant Arthur Anderson,<br />

and squeezed inves<strong>to</strong>rs and shareholder for money. Days before it collapsed, the <strong>to</strong>p brass liquidated<br />

their portfolios, knowing full well that everyone else who was invested would lose everything. The point<br />

of the movie is that corporate capitalism, especially when unregulated, can become psychopathized.<br />

2. What do you think is the most interesting point in the movie?<br />

The most striking part was around 69 minutes in, when the Enron employees were coolly discussing<br />

‘shutting down’ the California Power Grid, since this showed that it was not just about greed but a<br />

complete absence of morality.<br />

3. What is the most controversial statement you’ve heard?<br />

1:20 minutes in it was said that Ken Lay’s friendship with George W. Bush made is possible for Lay <strong>to</strong><br />

keep on perpetrating fraud with impunity. This well have been true (I suspect that it is), but it is<br />

obviously debatable and, in any case, controversial.<br />

4. What is the most important ethical issue that the movie is addressing? Please explain.<br />

Profits without integrity lead <strong>to</strong> large-scale financial loss and, therefore, that regulation is necessary <strong>to</strong><br />

prevent this.<br />

Bribery at the California DMVL The Case of Kari Scattaglia

Section I: The case I chose <strong>to</strong> discuss concerns a North Hollywood CA DMV<br />

employee, Kari Scattaglia, age 40, who used her position <strong>to</strong> sell commercial driver’s<br />

licenses (CDLs) <strong>to</strong> people who were not legally eligible <strong>to</strong> receive such licenses. In July<br />

<strong>2019</strong>, Scattaglia and a subordinate, Lisa Terraciano, age 52, pled guilty <strong>to</strong> issuing no less<br />

than 148 fraudulent CDLs in exchange for money. Scattaglia was sentenced <strong>to</strong> two years<br />

in prison. Terraciano has not yet been sentenced. Scattaglia and Terraciano were first<br />

arrested in November 2017. This paper will focus on Scattaglia.<br />

Scattaglia first joined the California DMV in 2007. During the subsequent 10<br />

years, she worked at several different California DMV locations and held several<br />

different positions. All of these positions were relating in some way or other <strong>to</strong> the<br />

issuing of licenses, and all of them involved Scattaglia having access <strong>to</strong> classified<br />

information, including the identities, addresses, phone numbers, and social securities of<br />

California residents who either had licenses or had lost their licenses or never had them<br />

<strong>to</strong> begin with.<br />

CDLs are enormously valuable. A CDL is needed <strong>to</strong> drive a vehicle that transports<br />

commercial inven<strong>to</strong>ry. All businesses that involve the transportation of goods need <strong>to</strong><br />

retain the services of drivers who have CDLs. Moreover, CDLs, unlike ordinary driver’s<br />

licenses, are hard <strong>to</strong> obtain. It is necessary <strong>to</strong> know how <strong>to</strong> operate and maintain<br />

different kinds of large trucks. It is also necessary <strong>to</strong> be familiar with complex<br />

regulations that are specific <strong>to</strong> such trucks, including regulations concerning the

transporting of hazardous substances, including dangerous chemicals, since a CDL is a<br />

legal prerequisite for transporting such substances.<br />

It therefore takes months of rather expensive training <strong>to</strong> acquire a CDL, with<br />

many of those who do undergo that training still unable pass the requisite tests, and<br />

there are therefore many people who have compelling financial reasons <strong>to</strong> obtain CDLs<br />

illicitly. Scattaglia knew who wanted CDLs, and she was able <strong>to</strong> provide them with CDLs.<br />

Because of the various clearances involved, Scattaglia needed some help, and she found<br />

a willing partner in Terraciano. Investiga<strong>to</strong>rs suspect that the two earned upwards of<br />

$200,000 from this scheme.<br />

CDLs are needed <strong>to</strong> operate buses, trac<strong>to</strong>r-trailers, and any vehicle that is<br />

transporting freight or hazardous materials, and serious disasters are therefore likely <strong>to</strong><br />

result from CDLs getting in<strong>to</strong> the wrong hands.<br />

Section II. <strong>Up</strong> <strong>to</strong> a point, Scattaglia’s motivations were clear: she wanted more<br />

money than she could possibly earn legitimately. She was stuck at a boring, low-paying,<br />

dead-end job. She had <strong>to</strong> work 40 hours/week, and commute another ten, for the<br />

privilege of earning just enough <strong>to</strong> pay rent on a studio apartment. She wanted more,<br />

but had no legitimate way of getting more; so she committed fraud.<br />

Of course, Scattaglia is not the only person who wants CEO-money but is stuck at<br />

a dead-end low-paying, the question arises. In fact, every single one of Scattaglia’s co-

workers would certainly have liked <strong>to</strong> make an extra few hundred thousand dollars. So<br />

why did Scattaglia commit fraud, whereas the others didn’t? Of course, a few of them<br />

might simply have lacked the requisite ingenuity, but what about the rest?<br />

Here we must point out that this case involved a pattern of fraud. This was not a<br />

single incident: it was ongoing criminal enterprise. A person of integrity might take<br />

conceivably take a single bribe—but not a hundred bribes. A single slip-up can be<br />

chalked up <strong>to</strong> exigent circumstances (e.g. an expensive life-critical medical procedure); a<br />

thousand incidents cannot be attributed <strong>to</strong> circumstance and must be explained in<br />

terms of a corrupt character. And that is what we are dealing with here. There are good<br />

people who make mistakes, but that is not what we are dealing with here, since 147<br />

cases of fraud are a criminal enterprise, not a mistake.<br />

Somebody who slips up once will not rationalize in the same way as a career<br />

criminal. To be sure, both will rationalize—but the rationalizations will be very different.<br />

First of all somebody who slips up just once is likely <strong>to</strong> feel remorse: somebody who<br />

commits one murder is likely <strong>to</strong> feel terrible guilt. A professional hitman is unlikely <strong>to</strong><br />

feel any guilt. Somebody who takes one bribe is likely <strong>to</strong> feel guilty about it, and they<br />

are likely <strong>to</strong> see their behavior as being due <strong>to</strong> exigent circumstances, coupled with<br />

weakness on their part. By contrast, somebody who commits theft or murder or fraud<br />

for a living is likely <strong>to</strong> rationalize by blaming ‘the system.’ ‘The whole system is corrupt,’

they may say. ‘I’m just getting my fair share.’ They may even self-identify as heroic<br />

Robin Hoods who are combatting an illegitimate system.<br />

Bazerman discusses cases of people ‘stumbling in<strong>to</strong> bad behavior’, saying that:<br />

[M]uch unethical conduct that goes on, whether in social life or work life,<br />

happens because people are unconsciously fooling themselves. They overlook<br />

transgressions — bending a rule <strong>to</strong> help a colleague, overlooking information that might<br />

damage the reputation of a client — because it is in their interest <strong>to</strong> do so (Bazerman,<br />

1).<br />

And surely what Bazerman is saying is true of many cases of misconduct—but not<br />

of the sort of misconduct involved in organized crime. Organized crime is not about<br />

lacking clarity; it is having it abusing it.<br />

Anand et al. mention various rationalizations and ploys used by wrong-doers:<br />

denial of responsibility (‘I didn’t do it’), denial of injuries (‘nobody was hurt’), denial of<br />

victim (‘nobody was hurt’), social weighing (‘in the big scheme of things, what I did<br />

wasn’t wrong and may even have been good’), appeal <strong>to</strong> a higher morality (‘petty laws<br />

are less important than existential fulfillment/religious dictates/…’), and the metaphor

of the ledger (‘I have done a lot of good, so I’m entitled <strong>to</strong> some slack’). Although we<br />

can’t know exactly what was going in in Scattaglia’s head, we know from investiga<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

that, first of all, she denied responsibility for as long as she could; and when that ceased<br />

<strong>to</strong> be an option, she did indeed tell them that she wasn’t hurting anybody and that, as<br />

she put when speaking <strong>to</strong> the lead investiga<strong>to</strong>r, ‘I don’t see why it’s such a big deal, I’m<br />

helping people, when you think about it.’ When she denied responsibility, she was<br />

obviously just lying; but she may well have believed, or half-believed, that she wasn’t<br />

really hurting anybody and that she was entitled <strong>to</strong> the bribe-money. But even though<br />

she may well have believed this, her ability <strong>to</strong> believe it was itself a consequence of a<br />

weak and corrupt character.<br />

Section III. The DMV, including the California DMV, does a creditable job of<br />

forestalling situations of this kind, this being why there have been extremely few such<br />

cases in the last forty years. In fact, the Scattaglia was in many ways unprecedented in<br />

DMV his<strong>to</strong>ry: for although there had been many cases of minor misconduct, this was<br />

the first documented case of organized and monetized fraud.<br />

In any case, the California DMV made the necessary changes. It altered its<br />

pro<strong>to</strong>cols so as <strong>to</strong> flag any cases of employee’s making unauthorized searches of records<br />

and also so as <strong>to</strong> require special clearances for records searches, usually involving a<br />

supervisor’s express consent. The California DMV also instituted au<strong>to</strong>mated internal

audits of records of licenses issued <strong>to</strong> people who had previously been denied them. Of<br />

course, we cannot how effective these measures, given that it’s barely been two years<br />

since Scattaglia’s arrest. But for what it’s worth, there has not been a single such<br />

incident during that time.<br />

Anand, V., Ashforth, B. E., & Joshi, M. (2004). Business as usual: The acceptance and<br />

perpetuation of corruption in organizations. Academy of Management<br />

Perspectives, 18(2), 39-53.<br />

Bazerman, Max and Tensbrunsel, Anne, 2011. Stumbling In<strong>to</strong> Bad Behavior New York<br />

Times. April 20, 2011<br />

Two DMV Employees Plead Guilty To Conspiring To Commit Bribery And Identity Fraud<br />

As Part Of Ongoing Investigation Of Commercial Licenses Issued To Unqualified Drivers.<br />

US Department of Justice. U.S. At<strong>to</strong>rney’s Office<br />

Eastern District of California. Nov. 3, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.justice.gov/usaoedca/pr/two-dmv-employees-plead-guilty-conspiring-commit-bribery-and-identity-fraud-part<br />

Stan<strong>to</strong>n, Sam. California DMV workers issued hundreds of bogus truck driving licenses<br />

for bribes, feds say. Sacramen<strong>to</strong> Bee. Nov. 2017. Retrieved from:<br />

https://www.sacbee.com/news/business/article180042781.html

Muller, Urs. The dirty dozen: how unethical behaviour creeps in<strong>to</strong> your organization.<br />

ESMT Berlin. Aug. 3, 2017. Retrieved from: https://esmt.berlin/knowledge/dirty-dozen-howunethical-behaviour-creeps-your-organisation<br />