Revitalization Edition - 1736 Magazine, Winter 2020

Revitalization of Downtown Augusta Edition - 1736 Magazine, Winter 2020

Revitalization of Downtown Augusta Edition - 1736 Magazine, Winter 2020

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

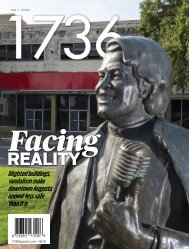

WINTER <strong>2020</strong><br />

The<br />

REVITALIZATION<br />

of DOWNTOWN<br />

AUGUSTA<br />

PRESERVATION EDITION<br />

• High cost, low payback<br />

constrain developers from<br />

tackling big projects<br />

<strong>1736</strong><strong>Magazine</strong>.com • $6.95<br />

• Historic Broad Street<br />

bank branch returning<br />

to former glory

MAGAZINE PARTNERS

A PRODUCT OF<br />

PRESIDENT<br />

TONY BERNADOS<br />

EDITOR<br />

DAMON CLINE<br />

DESIGNER<br />

CENTER FOR NEWS & DESIGN<br />

MAILING ADDRESS:<br />

725 BROAD STREET, AUGUSTA, GA 30901<br />

TELEPHONE:<br />

706.724.0851<br />

EDITORIAL:<br />

DAMON CLINE 706.823.3352<br />

DCLINE@AUGUSTACHRONICLE.COM<br />

ADVERTISING:<br />

706.828.2991<br />

©GANNETT All rights reserved. No part<br />

of this publication and/or website may be<br />

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or<br />

transmitted in any form without prior written<br />

permission of the Publisher. Permission is<br />

only deemed valid if approval is in writing.<br />

<strong>1736</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> and GANNETT buy all rights<br />

to contributions, text and images, unless<br />

previously agreed to in writing. While every<br />

effort has been made to ensure that information<br />

is correct at the time of going to print,<br />

GANNETT cannot be held responsible for the<br />

outcome of any action or decision based on the<br />

information contained in this publication.<br />

CONTENTS<br />

4<br />

PICTURE THIS<br />

6<br />

OUR VIEW<br />

11<br />

OTHER VOICES: PAUL KING<br />

14<br />

COVER STORY:<br />

THE PRICE OF PRESERVATION<br />

32<br />

AUGUSTA’S ARCHITECT:<br />

G. LLOYD PREACHER<br />

36<br />

BACK TO BANKING<br />

40<br />

15 PROPERTIES WITH POTENTIAL<br />

44<br />

LOST TO TIME<br />

70<br />

60<br />

54<br />

ALWAYS THERE<br />

60<br />

LIVING IN HISTORY<br />

70<br />

THE GREAT FIRE OF 1916<br />

76<br />

PARKING UPDATE<br />

78<br />

ON THE STREET:<br />

MARGARET WOODARD<br />

80<br />

BRIEFING<br />

82<br />

GRADING DOWNTOWN<br />

83<br />

FINAL WORDS<br />

COVER IMAGE BY: MICHAEL HOLAHAN<br />

IN THE NEXT ISSUE OF <strong>1736</strong><br />

Augusta’s urban core has nearly every type of business<br />

found in a typical city except one: a full-service<br />

supermarket. What will it take for the city in terms of<br />

population and demographics to attract – and retain – a<br />

grocery store to an area many have labeled a “food<br />

desert?”<br />

<strong>1736</strong>magazine.com | 3

PICTURE THIS<br />

4 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

The sun sets on downtown Augusta’s<br />

skyline as seen from the North<br />

Augusta Municipal Building in North<br />

Augusta, S.C. [MICHAEL HOLAHAN/<br />

THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

<strong>1736</strong>magazine.com | 5

OUR VIEW<br />

The home of Dr. Scipio S.<br />

Johnson, a prominent member<br />

of Augusta’s African-American<br />

community, sits at 1420<br />

Twiggs St. in the Bethlehem<br />

section of the Laney-Walker/<br />

Bethlehem neighborhood. The<br />

National Register of Historic<br />

Places-listed home is a prime<br />

candidate for certified historic<br />

rehabilitation. [DAMON CLINE/<br />

THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

MAKE PRESERVATION<br />

a city priority<br />

By DAMON CLINE<br />

LOSS OF BUILDINGS IN HISTORIC DISTRICTS<br />

ROBS FUTURE GENERATIONS OF CITY’S PAST<br />

Picture yourself as a tourist visiting Augusta for the first time.<br />

You and your spouse plan to stay at the James Hotel,<br />

a boutique inn fashioned from a century-old downtown<br />

building at the corner of Ninth and Telfair streets.<br />

After settling in, you meander across the scenic Barrett Plaza to<br />

have dinner at the trendy Locomotive restaurant inside Union Station,<br />

a turn-of-the-century train depot creatively re-purposed into a<br />

bustling mixed-use development.<br />

6 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

A row of shotgun shacks line a street in Olde Town. Some argue such structures are not worthy of<br />

preservation; others say they are cultural treasures that would be missed if demolished. [SPECIAL/<br />

HISTORIC AUGUSTA INC.-JAMES R. LOCKHART]<br />

You cap off your evening by sampling<br />

a couple of signature cocktails at Postal,<br />

an eclectic bar with rave reviews that’s<br />

housed in the Gothic Romanesqueinspired<br />

Federal Building just a block<br />

away.<br />

It sounds like a delightful experience,<br />

doesn’t it?<br />

Unfortunately, that particular alternative-reality<br />

scenario will never materialize.<br />

Those historic buildings no longer<br />

exist.<br />

Each was unceremoniously demolished<br />

long ago during an era when community<br />

leaders saw the old buildings as impediments<br />

to progress, rather than treasured<br />

architectural assets worth preserving.<br />

The city can never bring back the James<br />

Hotel, Union Station or the old Federal<br />

Building, but it can certainly work to prevent<br />

the neglect and destruction of other<br />

historic buildings in the central business<br />

district and its surrounding residential<br />

neighborhoods.<br />

It is a worthy endeavor. The link<br />

between economic development and the<br />

preservation of character-rich buildings<br />

and neighborhoods is undeniable.<br />

There is a reason Charleston, S.C.,<br />

and Savannah, Ga., perennially occupy<br />

slots in the top five U.S. cities to visit,<br />

as judged by readers of Travel + Leisure<br />

magazine.<br />

Those city’s historic preservation<br />

efforts, which began in the 1920s and<br />

1930s, have given them an incomparable<br />

“sense of place.”<br />

Increased tourism is merely one byproduct<br />

of historic preservation. Demographers<br />

have for years written about<br />

millennials’ penchant for living, working<br />

and playing in “unique” and “authentic”<br />

spaces.<br />

In Augusta, critical mass for such space<br />

can only be found in one area: the urban<br />

core.<br />

The metro area’s outer suburbs have<br />

their own quality-of-life benefits, but<br />

they lack the character, culture and<br />

charm found in the central business<br />

district and the historic neighborhoods of<br />

Olde Town, Harrisburg, Summerville and<br />

Laney-Walker/Bethlehem.<br />

Protecting these areas is paramount.<br />

Not all city officials and staffers “get it,”<br />

but fortunately, some do.<br />

“We want to make sure the majority<br />

of our neighborhoods in and around<br />

downtown are protected to the extent<br />

that they can be,” said Erik Engle, a senior<br />

planner with the Augusta Planning Commission<br />

who serves as staff liaison to the<br />

12-member city Historic Preservation<br />

Commission.<br />

Each section of the urban core has its<br />

own set of challenges. Olde Town, for<br />

example, is a city-designated historic district<br />

with preservation-minded rules and<br />

regulations that help protect its unique<br />

character. The other two urban neighborhoods<br />

have no such standards.<br />

In the historic Harrisburg-West End<br />

area – a once-vibrant working-class<br />

community whose decline was accelerated<br />

by the loss of the city’s textile industry<br />

– revitalization efforts are primarily the<br />

domain of grassroots organizations such<br />

as Turn Back The Block.<br />

But in the war against blight, such<br />

nonprofits face an uphill battle. The sheer<br />

volume of decaying late 19th and early<br />

20th century homes is overwhelming.<br />

“Unfortunately, we’re seeing a lot of<br />

those neighborhoods fall apart, in a way,”<br />

Engle said. “Would we like to see more<br />

preservation in those areas? Absolutely.<br />

But it really has to come from the neighborhood<br />

itself.”<br />

The Laney-Walker/Bethlehem neighborhood<br />

was a city-designated district<br />

until its residents voted to shed the<br />

designation years ago. Although the<br />

historically African-American neighborhood<br />

is currently the focus of a city hotel<br />

tax-funded revitalization initiative, the<br />

program’s primary solution to dealing<br />

with abandoned or dilapidated homes has<br />

been demolition rather than restoration.<br />

Vacant lots in the neighborhood are<br />

abundant. Some newer homes and multifamily<br />

developments built during the past<br />

several years – such as those developed<br />

by the quasi-governmental Augusta<br />

Neighborhood Improvement Corp.<br />

and a host of U.S. Housing and Urban<br />

Development-funded community housing<br />

development organizations – blend<br />

in nicely with the surrounding neighborhood.<br />

Others do not.<br />

<strong>1736</strong>magazine.com | 7

RIGHT: A cluster of stately Victorian-era homes line Greene Street<br />

in the locally designated downtown historic district, which offers<br />

special protection to historic structures. BELOW: A sunrise over the<br />

Harrisburg neighborhood illuminates historic commercial buildings<br />

at the corner of Broad Street and Crawford Avenue. [SPECIAL/<br />

HISTORIC AUGUSTA INC.-JAMES R. LOCKHART]<br />

“Even though the city has put a lot of<br />

money and time into restoring Laney-<br />

Walker, they’re not restoring it in the<br />

sense of historic preservation,” said Erick<br />

Montgomery, executive director of Historic<br />

Augusta Inc.<br />

To some Baby Boomers, the urban<br />

core’s century-old shotgun shacks are<br />

symbols of hardscrabble poverty that<br />

should be eliminated. As Augusta Commissioner<br />

Marion Williams famously said<br />

in 2015, the structures “are not history to<br />

any black man” worth preserving.<br />

Perhaps. But race aside, the modest<br />

row houses throughout the inner city<br />

are an integral part of Augusta’s history.<br />

They are unique. They tell the city’s<br />

story to future generations of visitors and<br />

residents.<br />

And from a practical standpoint, such<br />

homes have potential to be affordable<br />

“retro” housing solutions for a new generation<br />

of homeowners, who have shown<br />

an affinity for urban living in smaller<br />

dwellings.<br />

Is every old home and commercial<br />

building in the urban core worth saving?<br />

No. Some are far too gone to rehabilitate.<br />

Some pose a public-safety hazard. Some<br />

are dens of illicit activity. Some decrease<br />

the value of surrounding properties. And<br />

in some rare instances, some buildings<br />

do need to be torn down in the name<br />

of progress – such as the demolition of<br />

the old Belk department store and four<br />

others on the 800 block of Broad Street to<br />

make way for the Augusta Common, the<br />

urban park that city founder Gen. James<br />

Oglethorpe planned more than 250 years<br />

earlier.<br />

As much as it may pain preservationists,<br />

some old buildings do need to be removed.<br />

Maintenance appears to be the key to<br />

successfully preserving culturally-rich<br />

buildings in Augusta’s urban core. Simply<br />

put, buildings become dilapidated when<br />

the community allows them to become<br />

dilapidated.<br />

“Ideally, the No. 1 goal is to maintain<br />

what you have – maintain what is existing,”<br />

Engle said. “At the end of the day,<br />

it does honestly look better when people<br />

just kind of maintain what’s there.”<br />

When it comes to revitalizing the urban<br />

core, preservation should be the city’s<br />

default setting, particularly in the city’s<br />

central business district, where the vast<br />

majority of buildings are commercial<br />

properties.<br />

As the heart of the city, the central<br />

business district is the one place where<br />

people from all parts of the metro area<br />

congregate. It also is the place where<br />

most first-time visitors develop their<br />

impressions of Augusta.<br />

Code-enforcement is crucial. A certain<br />

level of tolerance for the cash-strapped<br />

homeowner who can’t properly maintain<br />

a home is understandable, but should<br />

real estate investors and businesspeople<br />

owning dilapidated commercial properties<br />

in the city center receive such leniency?<br />

8 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

The court of public opinion would likely say “no.”<br />

Some cities across the country have<br />

experimented with vacant-building fees and<br />

increased property tax assessments on unused<br />

or distressed properties to motivate owners to<br />

bring their buildings up to snuff or sell them.<br />

Such programs have seen mixed results, but<br />

some in Augusta would be willing to advocate<br />

for public-sector solutions to solve the problem<br />

of neglected private properties, some of<br />

which are historically, culturally and architecturally<br />

significant.<br />

“What is the city able to do and what are<br />

they willing to do to bring these do-nothing<br />

property owners to their senses – to either<br />

sell it, to let somebody else do it or to do some<br />

minimal thing to keep it from falling down from<br />

neglect?” Montgomery said.<br />

Augusta’s urban core has lost far too many<br />

architectural treasures during the past 60<br />

years, in both its residential areas and its central<br />

business district.<br />

After a decades-long period of decline, those<br />

areas are inching toward vibrancy in this new<br />

millennium. If there was ever a time for community<br />

leaders, public officials and the general<br />

public to unite behind historic preservation<br />

efforts, that time is now.<br />

It’s time to stop robbing future visitors and<br />

residents of the city’s storied past.<br />

A sign at the corner<br />

of Ninth and Hopkins<br />

streets in the Laney-<br />

Walker/Bethlehem<br />

neighborhood advertises<br />

future construction by<br />

one of several entities<br />

building new housing<br />

in the historic African-<br />

American neighborhood.<br />

[DAMON CLINE/THE<br />

AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

10 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

OTHER VOICES<br />

Paul King stands outside his Rex Property & Management LLC office on<br />

Monte Sano Avenue, where he oversees more than 200 residential units<br />

throughout Augusta’s urban core. [DAMON CLINE/THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

PAST IS PREVIEW:<br />

Historic preservation<br />

incentives kick-start<br />

downtown revitalization<br />

By PAUL KING<br />

Guest Columnist<br />

In a shockingly hot June 1981, a young engineer moved 1,100<br />

miles from coastal New Hampshire to Augusta.<br />

What he found when looking for a home were some nice<br />

new apartment complexes along Washington Road and some<br />

very attractive historic homes in the Olde Town neighborhood that<br />

had been recently rehabbed, converted to apartments through the<br />

preservation technique called “adaptive reuse.”<br />

Yes, that engineer was me.<br />

Not knowing the area, I took the conservative route and picked<br />

the apartment complex. One year later, I couldn’t move to Olde<br />

Town fast enough.<br />

<strong>1736</strong>magazine.com | 11

King Kat and the Elders perform at downtown Augusta’s Stillwater Taproom in this file image from 2018. Historic preservationists see a direct link between<br />

today’s vibrant downtown economy and tax-assisted building renovation efforts that began more than four decades ago. [THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

Young, fun and interesting people<br />

were moving into the changing neighborhood,<br />

where historic-preservationfor-profit<br />

pioneer Peter Knox Jr. –<br />

“Mr. Pete,” as many knew him – and<br />

his company, Downtown Augusta Inc.<br />

were changing the face of the neighborhood<br />

using the historic preservation tax<br />

credits created through the Tax Reform<br />

Act of 1976.<br />

A few small investors joined in<br />

the use of preservation tax credits to<br />

rehab downtown buildings – the initial<br />

efforts in revitalizing Augusta’s urban<br />

core had begun.<br />

In 1986, the Tax Reform Act created<br />

restrictions limiting the use of federal<br />

historic preservation tax credits. This<br />

led to a slowdown in tax credit projects<br />

nationally and in Augusta.<br />

Georgia state historic preservation<br />

tax credits first became available<br />

in 2002 and helped renew interest<br />

in redevelopment through historic<br />

preservation in Olde Town and the<br />

central business district, where Bryan<br />

Haltermann had led many Broad Street<br />

tax credit projects, including buildings<br />

housing the Pizza Joint, Metro, and Art<br />

on Broad, promoting a generational<br />

return to the urban core.<br />

Also, in 2002 the Georgia Cities<br />

Foundation revolving loan fund was<br />

created with a preference for downtown<br />

projects with historic preservation<br />

components. A Georgia Cities<br />

Foundation loan would then be used to<br />

help fund the initial construction work<br />

converting the former J.B. White’s<br />

department store on the 900 block of<br />

Broad into residential condominiums<br />

with first floor retail tenants.<br />

HISTORIC<br />

PRESERVATION<br />

CHALLENGES IN<br />

AUGUSTA<br />

• Conflicts between historic preservation<br />

and creating density<br />

• Fickle nature of tax credit programs<br />

• Economy-of-scale difficulties in using<br />

credits on small buildings<br />

• Ongoing public education challenges<br />

in urban core<br />

• Underutilized historic buildings<br />

with market-rate residential potential<br />

(i.e., the former Bon Air and<br />

Richmond hotels)<br />

• Large historic properties facing<br />

cost-prohibitive rehabilitations under<br />

current market conditions (i.e., the<br />

Marion and Lamar buildings)<br />

• Shortage of downtown parking and<br />

lack of a parking-management plan<br />

PRESERVATION continues on 42<br />

12 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

COVER STORY<br />

Price The of<br />

Preservation<br />

Saving Augusta’s old buildings comes with risks, rewards<br />

Story by DAMON CLINE<br />

Photos by MICHAEL HOLAHAN<br />

Architect Brad King, of 2KM<br />

Architects, stands outside his<br />

firm’s office, the historic Jacob<br />

Phinizy home in Augusta.<br />

14 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

<strong>1736</strong>magazine.com | 15

Mark Donahue, president of Peach Contractors, stands with before-and-after photos of the Lowrey Wagon Works building at<br />

912 Ellis St. Donahue’s company completed a historic restoration of the 160-year-old building into 19 loft-style apartments in 2016.<br />

Mark Donahue parks<br />

his SUV in front of<br />

the 102-year-old<br />

building at 941 Ellis<br />

St.<br />

He grabs a key from an oversize ring and<br />

unlocks the front door that leads to a dozen<br />

brand-new loft-style apartments.<br />

He knows every nook and cranny in the<br />

two-story building, which once housed a<br />

handkerchief factory, a piano store and a<br />

warehouse before entering a long period of<br />

vacancy.<br />

But Donahue is not a building resident –<br />

he’s the owner.<br />

His company, Peach Contractors,<br />

is responsible for turning the formerly<br />

dilapidated E.M. Andrews Furniture Co.<br />

warehouse into a 12-unit complex.<br />

“This building had a hole in the roof big<br />

enough to drop a car through when we<br />

purchased it,” Donahue says while climbing<br />

stairs his carpenters built not more than a<br />

year ago.<br />

After concluding his tour, Donahue gets<br />

back in his tool-littered Tahoe and heads<br />

east toward a Victorian-era home at 448<br />

Greene St.<br />

The 19th century residence – like the Ellis<br />

Street warehouse – is a property Donahue<br />

saved from irreparable decay.<br />

“This is the gem. I got an award from the<br />

state of Georgia for this one,” he says nonchalantly<br />

as he pulls to the curb.<br />

The elegant three-story home was built in<br />

the 1870s for Reuben B. Wilson, a wealthy<br />

Augusta grocer. It is known to preservationists<br />

as the Zachariah Daniel House,<br />

named for the home’s second owner, who<br />

also happened to be in the grocery business.<br />

16 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

Buildings on the corner of Ninth and Telfair streets in downtown Augusta are being<br />

marketed for renovation into office, retail and residential space.<br />

Donahue’s company meticulously<br />

restored the condemned<br />

property’s bracketed eaves, hooded<br />

windows and decorative marble<br />

masonry joints – called quoins – to<br />

restore the home into what some<br />

consider the city’s most outstanding<br />

example of Second Empire<br />

architecture.<br />

When asked about the condition<br />

of the property when he bought it<br />

in 2016, his answer is simple: “Very<br />

bad.”<br />

Today the 6,500-square-foot<br />

estate houses 10 income-producing<br />

apartments, all of which lease as<br />

quickly as those in his half-dozen<br />

other downtown buildings.<br />

Generating revenue is the<br />

ultimate goal for any real estate<br />

investor, but this native New<br />

Yorker also has ulterior motives.<br />

“I love this stuff – I restore these<br />

buildings because I love doing it.<br />

I feel like I’m giving something<br />

back, I really do,” says Donahue, an<br />

Augusta resident for more than 30<br />

years. “I know this sounds corny,<br />

but I feel like these buildings would<br />

have been lost. I feel like I’m a caretaker<br />

for the next generation.”<br />

Donahue isn’t the only developer<br />

to find financial success by restoring<br />

vacant buildings in Augusta’s<br />

downtown historic district. Local<br />

preservationists only wish there<br />

were more Mark Donahues in the<br />

city, which has dozens of historic<br />

buildings threatened by neglect,<br />

encroachment and abandonment.<br />

PRESERVATION<br />

OPPORTUNITIES ABOUND<br />

Founded by Gen. James<br />

Oglethorpe in <strong>1736</strong>, Augusta is a<br />

target-rich environment for historic<br />

preservation.<br />

“The architectural history of<br />

Augusta is interesting,” said Erick<br />

Montgomery, executive director<br />

of Historic Augusta Inc., the city’s<br />

lead preservation organization.<br />

“We have examples of every style<br />

since the Federal period. We don’t<br />

really have anything that survived<br />

the Colonial period, but there are<br />

a lot of historically significant<br />

buildings.”<br />

The city’s urban core is home to<br />

more than a half-dozen historic<br />

districts listed on the National<br />

Park Service’s National Register of<br />

Historic Places. Overlaying those<br />

National Register Historic Districts<br />

are three city-designated historic<br />

districts: Downtown, which<br />

encompasses the bulk of the central<br />

business district; Olde Town,<br />

which covers the east Augusta<br />

area also known as “Pinched Gut”;<br />

and Summerville, which includes<br />

most areas of the tony “Hill”<br />

neighborhood.<br />

Summerville’s city designation<br />

was established in 1994; Downtown<br />

in 2002; and Olde Town in 2006.<br />

Each area – to varying degrees<br />

– has architecturally, culturally or<br />

historically significant properties<br />

in danger of being lost to inappropriate<br />

alterations, demolition or<br />

decay.<br />

Many of those buildings have<br />

18 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

ABOVE: Davis Beman<br />

of Blanchard & Calhoun<br />

Commercial checks his cell<br />

phone inside one of the<br />

vacant buildings at Ninth<br />

and Telfair streets that he<br />

is marketing as mixed-use<br />

space.<br />

RIGHT: The interior of<br />

one of the 19th century<br />

buildings at Ninth and<br />

Telfair streets reveals<br />

decades of neglect.<br />

<strong>1736</strong>magazine.com | 19

Beverly Barnhart, founding principal for Davidson Fine Arts School, speaks to the crowd of alumni, faculty, and others gathered<br />

at the old school building in this November 2015 photo. The building was demolished two months later because of heavy water<br />

damage it suffered while vacant for 18 years. [FILE/THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

been documented since 2006<br />

by Historic Augusta’s annual<br />

“Endangered Properties” list.<br />

The Zachariah Daniel House,<br />

for example, made the list in 2015,<br />

a year before Donahue acquired<br />

it. The 160-year-old Lowrey<br />

Wagon Works building, across<br />

the street from the E.B. Andrews<br />

warehouse, had been listed since<br />

2008. Donahue turned the Lowrey<br />

building into a 19-unit apartment<br />

building in 2016.<br />

The three-story Lowrey building<br />

is particularly rich in history.<br />

Situated at the corner of Ninth and<br />

Ellis streets, it was confiscated by<br />

the Confederacy during the Civil<br />

War to be a shoe factory. After the<br />

war it served as a school for freed<br />

black children until J.H. Lowrey<br />

reestablished it as a wagon factory<br />

in 1866.<br />

It remained in the family until<br />

the death of Lowrey’s only son,<br />

Henry, in 1925, at which point it<br />

was purchased as a warehouse for<br />

the former J.B. White’s department<br />

store at 936 Broad St. It<br />

housed several other commercial<br />

operations before entering a<br />

decades-long period of neglect<br />

during downtown Augusta’s nadir.<br />

Compiling the Endangered<br />

Properties list is Historic Augusta’s<br />

primary means of trying to save<br />

properties it deems historically<br />

significant.<br />

Contrary to public perception,<br />

the nonprofit organization has no<br />

enforcement power. It also lacks<br />

the funds to acquire buildings it<br />

deems worthy of saving, though it<br />

has made rare exceptions for properties<br />

in urgent need of protection,<br />

such as the home of C.T. Walker in<br />

the historic Laney-Walker district.<br />

Unless a property is protected by<br />

one of Historic Augusta’s 42 preservation<br />

easements – something<br />

property owners grant to receive<br />

tax deductions – the organization<br />

can’t legally tell owners what to do<br />

with their buildings.<br />

“We have zero power except the<br />

power of public persuasion and<br />

public opinion,” Montgomery says.<br />

Even owners of federal National<br />

Register of Historic Places-listed<br />

properties – of which there are<br />

20 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

Historic Augusta Executive Director Erick<br />

Montgomery talks about new properties that<br />

have been added to the list of endangered<br />

properties during a press conference in Augusta<br />

on Nov. 7, including the former Augusta Trunk<br />

Factory building at 840 Reynolds St.<br />

more than four dozen in Augusta – are not forbidden<br />

from making architectural changes or demolishing such<br />

buildings unless the structures are in one of the three<br />

locally designated districts, in which case alterations<br />

and city-code violations become the purview of the<br />

city’s Historic Preservation Commission.<br />

The commission has the authority to regulate the<br />

outside appearance of properties as well as delay – but<br />

not always prevent – demolition.<br />

In some cases, Historic Augusta’s PR campaign and<br />

city enforcement actions aren’t enough to save structures<br />

from the wrecking ball or being allowed to implode<br />

on their own, something preservationists call “demolition<br />

by neglect.”<br />

Inclusion on Historic Augusta’s endangered list, for<br />

example, hasn’t stopped several buildings – such as the<br />

Denning House at 905 Seventh St. and the Southern<br />

Bell Exchange Building at 937 Ellis St. – from steadily<br />

deteriorating.<br />

Other buildings that were listed as endangered – such<br />

as the old John S. Davidson School at the corner of 11th<br />

and Telfair streets and the Immaculate Conception<br />

Academy building at 1016 Laney-Walker Blvd. – were<br />

demolished despite public protestations.<br />

Occasionally, the attention results in a victory,<br />

such as the five-year stay of execution for the former<br />

Congregation Children of Israel Synagogue, a cityowned<br />

building at 525 Telfair St., and the relocation of<br />

the Trinity Christian Methodist Episcopal Church at 731<br />

Taylor St.<br />

<strong>1736</strong>magazine.com | 21

Architect Brad King, of 2KM Architects, stands inside the historic Jacob Phinizy home in Augusta.<br />

The synagogue building, which<br />

the city used as extra office space, is<br />

scheduled to be demolished unless<br />

a grassroots organization follows<br />

through on its plans to turn the<br />

property into the Augusta Jewish<br />

Museum by 2021.<br />

The Trinity CME church was<br />

scheduled for demolition by<br />

Atlanta Gas Light as part of a soil<br />

remediation project near a former<br />

coal-gas plant until an Augusta<br />

Canal Authority-secured grant<br />

funded the building’s move onto<br />

a new foundation 250 feet away in<br />

2018.<br />

The best strategy to saving<br />

endangered properties is finding<br />

preservation-minded owners with<br />

the rare combination of vision and<br />

capital.<br />

Montgomery acknowledges it is<br />

much easier, cheaper and less risky<br />

for developers to invest in new<br />

construction than rehabilitate old<br />

buildings.<br />

“Money is almost always the<br />

issue,” he said. “Either they<br />

(property owners) don’t have it or<br />

they don’t want to spend it. Then<br />

you have people that are interested<br />

and willing who just don’t have<br />

the funds or the means to raise the<br />

funds.”<br />

MAKING THE<br />

NUMBERS WORK<br />

The biggest incentive for developers<br />

to invest in preserving old<br />

buildings are state and federal historic<br />

tax credits. When combined,<br />

the credits can knock off up to 45%<br />

of the cost for certified rehabilitation<br />

projects in Georgia.<br />

The preservation credits are<br />

“sold” to third parties – who use<br />

them to offset their state and federal<br />

income tax liabilities – creating<br />

cash-back incentives for historic<br />

rehabilitation projects that would<br />

otherwise be financially unfeasible.<br />

The tax credits’ multi-step<br />

approval process, which is managed<br />

by the National Park Service,<br />

requires developers to submit<br />

detailed pre-construction rehabilitation<br />

plans to ensure historic<br />

or architecturally significant<br />

characteristics are not altered.<br />

Owners also must prove the work<br />

was performed to detailed standards<br />

through photographs and<br />

inspection.<br />

Historic property investors also<br />

are able to take advantage of federal<br />

“Opportunity Zone” tax benefits<br />

created under the Tax Cuts and Jobs<br />

Act of 2017. The provision provides<br />

tax incentives for re-investing<br />

unrealized capital gains into economically-distressed<br />

census tracts.<br />

Virtually all of Augusta’s urban core<br />

falls within federal Opportunity<br />

Zone boundaries.<br />

Donahue said the preservation<br />

tax-credit process is complicated<br />

and takes about a year, but he<br />

acknowledges he couldn’t have<br />

22 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

PROFILES IN PRESERVATION<br />

The home of C.T. Walker at 1011 Laney-Walker Blvd. is being<br />

restored by Historic Augusta Inc. after years of dilapidation<br />

under private ownership. [SPECIAL PHOTOS]<br />

C.T. WALKER HOME<br />

1011 Laney-Walker Boulevard<br />

The Rev. Charles Thomas<br />

Walker (1858-1921) was an<br />

internationally acclaimed<br />

minister and a pillar of<br />

Augusta’s African-American<br />

community.<br />

One would not know that,<br />

however, by looking at the<br />

condition of the house he<br />

once called home at 1011<br />

Laney-Walker Blvd.<br />

The modest two-story<br />

house, which served as<br />

Walker’s residence from 1905<br />

until his death in 1921, spent<br />

so many years in disrepair<br />

that it was named one of<br />

10 “Places in Peril” by the<br />

Georgia Trust for Historic<br />

Preservation.<br />

But the property’s decadeslong<br />

decay came to an end in<br />

November 2016 when Historic<br />

Augusta Inc. was able to<br />

acquire the home after working<br />

for years with the heirs of<br />

The Rev. Charles T. Walker,<br />

founder of Tabernacle Baptist<br />

Church and the namesake of<br />

C.T. Walker Traditional Magnet<br />

School, was a nationally known<br />

minister in the early 20th<br />

century.<br />

its previous owner. The local preservation group is in the process of<br />

rehabilitating the 135-year-old house into a historic site, something<br />

that could be a catalyst for further preservation in the historic<br />

Laney-Walker neighborhood.<br />

The home is one of the few residences remaining on Laney-<br />

Walker Boulevard, which is named for Walker and renowned<br />

African-American educator Lucy Craft Laney.<br />

Walker also is the namesake for C.T. Walker Traditional Magnet<br />

School, and was the founder of Tabernacle Baptist Church, whose<br />

pews during the late 19th and early 20th centuries attracted everyone<br />

from freed slaves to President Taft.<br />

Walker’s widow, Violet Q. Franklin Walker, lived in the home until<br />

her death in 1928.<br />

Real estate investors find large, vacant buildings in the downtown historic<br />

district, such as the Marion Building, shown, too costly to renovate at current<br />

lease rates. [FILE/THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

financed most of his projects without them. Credits help foot the bill<br />

for costs that wouldn’t be encountered in new construction, such as<br />

restoring intricate millwork or bringing a century-old structure up to<br />

modern safety codes.<br />

Donahue said hundreds of thousands of dollars went toward<br />

improvements at the Lowrey, E.M. Andrews and Zachariah Daniel<br />

House buildings before he could even start building the income-producing<br />

loft apartments.<br />

“We spent $100,000 just on fire alarms and sprinklers,” Donahue<br />

said of the E.M. Andrews building. “Bringing everything up to meet<br />

all the current codes, that’s where a lot of the big money is. It’s more<br />

costly to do an old building than it is to do the identical building brand<br />

new.”<br />

Davis Beman, head of Blanchard & Calhoun Real Estate’s commercial<br />

division, is well-versed in helping investors and owners make<br />

historic redevelopment deals “work.” Beman himself is an investor in<br />

the historic Red Star Building at 531 Ninth St., a century-old building<br />

known for housing businesses catering to black train travelers during<br />

the segregation era. The property is now home to four residential<br />

units as well as the offices of attorney M. Austin Jackson and the<br />

contract-labor firm Austin Industrial.<br />

Beman said historic renovation projects are most convenient for<br />

property owners who will be the building’s end user, as they are not<br />

dependent on the ebbs and flows of the local rental market to recoup<br />

the investment.<br />

Notable end-user project examples include TaxSlayer’s purchase<br />

of the former Family Y building at 945 Broad St. to serve as its new<br />

headquarters, and Loop Recruiting’s purchase of the long-vacant Bee<br />

Hive building at 972 Broad St. to serve as its main office and that of its<br />

co-investor, Milestone Construction. Both structures far exceed the<br />

50-year-old threshold for a building to be considered historic.<br />

Investors restoring buildings strictly for rental income must weigh<br />

the redevelopment costs against Augusta’s current demand for<br />

24 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

commercial and residential space, Beman said. They also must take<br />

into account the city’s current lease rates, which are rising but still<br />

comparatively low compared to peer cities.<br />

A final consideration is a property’s potential “density” – the<br />

maximum number of income-generating units it can yield. New<br />

buildings are designed with density in mind; historic buildings are<br />

often constrained by their original footprints and interior floorplans.<br />

Beman is currently marketing an amalgam of 19th century structures<br />

for redevelopment just north of the Red Star Building. The<br />

properties, which occupy the northwest corner of Ninth and Telfair<br />

streets, are individually owned by Kevin Steffes, founder of Vision<br />

Wireless, and Frank and Adele Damiano, the proprietors of the<br />

Damiano Co. dry goods store.<br />

Steffes bought his vacant buildings, which include the former<br />

Georgia State Floral Distributors warehouse, in 2017 for $175,000 to<br />

house his managed mobile-services firm. He later chose to locate in<br />

the Augusta University office tower at 699 Broad St. The Damianos,<br />

which occupy space in one of two buildings it owns on the block, are<br />

seeking to sell so they can retire.<br />

Like many owners of older buildings, Beman said Steffes and the<br />

Damianos are hopeful increased demand for downtown Augusta real<br />

estate will produce an interested tenant or buyer. Each party has the<br />

luxury of waiting, as their cost basis in the properties are relatively<br />

low.<br />

“It’s a renovation project that is going to be pretty costly, and its<br />

going to take time for the rental rates to justify the cost of building<br />

it out,“ acknowledges Beman, who is marketing the buildings as a<br />

mixed-use package deal.<br />

The property cluster’s proximity to the Augusta Judicial Center,<br />

the U.S. District Court complex and the newly built Augusta Fire<br />

Department station make it a good candidate for upper-floor apartments<br />

with ground-level office and retail tenants.<br />

The former warehouse building is a wide-open “blank slate,”<br />

Beman’s colleague Alex Griffin said.<br />

“This could be an awesome restaurant or coffee shop on the<br />

corner,” he said.<br />

One of the block’s vacant buildings already has a residential lineage;<br />

it was used as a boarding house for railroad workers during the<br />

early 20th century. The buildings are a block away from the site of the<br />

former Union Station train depot, an ornate Spanish Renaissancestyled<br />

building demolished nearly five decades ago. The property on<br />

which it sat is now occupied by the U.S. Postal Service’s downtown<br />

office, a product of 1970s-era institutional architecture.<br />

Beman said the Steffes and Damiano buildings still retain their 19th<br />

century character. The warehouse, for example, has brick arches with<br />

cast-iron supports where large windows used to be. The adjoining<br />

building also has large windows that could once again be opened up to<br />

natural light.<br />

The building was bricked over after sustaining damage during<br />

the 1970 Augusta riot. Windows broken during the unrest were left<br />

untouched, and are still visible from the inside.<br />

“They never replaced the glass,” Beman said. “They just put bricks<br />

over the front.”<br />

OLD BUILDINGS, NEW CHALLENGES<br />

Some old buildings are easier to restore than others. An architect<br />

often is needed to determine just how much work is needed to breathe<br />

new life into a long-vacant property.<br />

ENTERPRISE MILL<br />

1450 Greene St.<br />

PROFILES IN PRESERVATION<br />

The historic renovation of Enterprise Mill in the late 1990s made<br />

it cool to “live, work and play” in downtown Augusta again.<br />

The former textile mill, whose oldest section dates back to an<br />

1848 flour mill, was purchased in 1997 by Augusta businessman<br />

Clayton P. Boardman III as an adaptive-reuse project to turn the<br />

19th century industrial property into a mixed-use facility with<br />

residential, office and retail units.<br />

Having been shuttered in 1983 by former owner The Graniteville<br />

Co., the $15 million project involved removing more than 5,000<br />

tons of debris, restoring the building’s original 500 windows and<br />

re-roofing the entire structure.<br />

Today, the 260,000-square-foot complex is home to dozens of<br />

residents, several large commercial tenants and the Augusta Canal<br />

National Heritage Area Interpretive Center, which gives visitors<br />

a glimpse of what mill life was like during the city’s Industrial<br />

Revolution heyday.<br />

The property is replete with vestiges of its past, including<br />

hand-painted signs on interior walls, hardwood floors embedded<br />

with metal pieces used during the spinning process and a working<br />

turbine powered by the flowing waters of the Augusta Canal.<br />

The massive project was not a high-profit venture for the developer<br />

– Boardman sold the property in 2006 for $13 million – but it<br />

did give Augusta one of its most treasured downtown assets.<br />

An aerial view of Enterprise Mil in 1994 shows it at the height of<br />

its decay. [FILE PHOTOS/THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

<strong>1736</strong>magazine.com | 25

PROFILES IN PRESERVATION<br />

Jack Weinstein, president of the Augusta Jewish Museum (left)<br />

stands outside the future Augusta Jewish Museum along with<br />

Studio 3 Design Group architect Ellen Pruitt and Historic Augusta<br />

Executive Director Erick Montgomery. [FILE/THE AUGUSTA<br />

CHRONICLE]<br />

CONGREGATION CHILDREN<br />

OF ISRAEL SYNAGOGUE<br />

525 Telfair St.<br />

Jewish families have been<br />

in Augusta since 1802. But<br />

a purpose-built synagogue<br />

for them to worship in didn’t<br />

come until 1869, when the<br />

cornerstone was laid for what<br />

would be the Congregation<br />

Children of Israel Synagogue<br />

on Telfair Street.<br />

The Greek Revival-style<br />

temple they completed in<br />

1872 is believed to be the<br />

oldest building in Georgia<br />

built as a synagogue.<br />

In 1950, after worshiping at<br />

the building nearly 80 years,<br />

the congregation moved to<br />

a new synagogue on Walton<br />

Way. The building was sold to<br />

engineering firm Patchen and<br />

Zimmerman, which used it<br />

as an office. It was later purchased<br />

by the city of Augusta<br />

to house various departments<br />

over the years.<br />

When the city announced<br />

plans in 2015 to demolish the<br />

building, and an even older<br />

adjacent building called the<br />

The Jewish Synagogue at 525<br />

Telfair St., depicted in this early<br />

20th century postcard, was<br />

dedicated in 1869. The building<br />

was used until the congregation<br />

moved to the Summerville<br />

neighborhood in the 1950s.<br />

[SPECIAL]<br />

Court of the Ordinary, area Jewish families and historic preservationists<br />

rallied to protest the destruction.<br />

The Augusta Jewish Museum board was organized to protect<br />

the buildings by creating an educational center for residents and<br />

visitors to learn about the Jewish community’s history and contributions<br />

to the metro area. <br />

The city agreed to give the newly formed group five years – until<br />

July 2021 – to raise the money, do the restoration and open the<br />

museum before the buildings revert back to city ownership and<br />

eventual demolition.<br />

Brad King, a project architect at Augusta’s 2KM Architects, has<br />

served as an adviser on several preservation projects, including his own<br />

employer’s move to 529 Greene St., the former home of Jacob Phinizy,<br />

a former Augusta mayor and Georgia Railroad Bank president.<br />

The property, built in 1882, also housed the Poteet Funeral Home<br />

during the latter half of the 20th century. The Second Empire-styled<br />

structure spent nearly a decade in decay before 2KM moved in during<br />

2012. The work, which included discovering previously hidden wall<br />

paintings, was completed in 2014.<br />

King, who received his historic preservation certificate while earning<br />

a master’s degree at the University of Cincinnati, said several<br />

“test fit” plans he has conducted for clients in downtown Augusta<br />

never came to fruition because they uncovered costs the investor<br />

hadn’t anticipated.<br />

“I don’t think owners always know, going into it, what they’re getting<br />

themselves into,” King said. “It’s our job as architects to educate<br />

them on what it’s going to take, especially if they’re trying to get tax<br />

credits.”<br />

The obstacles to bonafide historic renovations can be plentiful.<br />

Tax credit rules might require, for example, a developer spend more<br />

repairing old wood-frame windows instead of buying newer, more<br />

energy-efficient ones. Sometimes there is costly asbestos and lead<br />

abatement. And there are almost always compliance issues with<br />

modern safety codes and the Americans with Disabilities Act.<br />

“A lot of these buildings were not made ADA-accessible,” King<br />

said. “If it wasn’t built with an elevator shaft and your tenant space is<br />

on the second floor, you’ve got to put in an elevator.”<br />

Modern safety codes also require two forms of egress – unobstructed<br />

exit paths. That makes large, multi-story structures with<br />

only one stairwell extremely expensive to rehabilitate, King said.<br />

In the case of the Lamar and Marion buildings – two of downtown<br />

Augusta’s tallest vacant historic buildings – constructing a second<br />

stairwell in either building that would simultaneously meet code and<br />

satisfy tax-credit standards could easily top $1 million, a sum that<br />

equals the last recorded sales price of both buildings combined.<br />

Increasing construction costs, coupled with downtown Augusta’s<br />

current rental rates – which are roughly 30% below the national average,<br />

according to the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis – are the<br />

primary reason many of the city’s largest vacant buildings remain<br />

idle.<br />

Beman notes that Georgia’s tax-credit law creates a catch-22. The<br />

time and expense of obtaining state and federal credits is the same<br />

whether a developer rehabilitates a 1,000-square-foot building or<br />

a 100,000-square-foot building, creating a disincentive to obtain<br />

credits on small projects.<br />

Compounding the problem in Georgia is the large gaps in the<br />

maximum credits allowed under the state’s three-tier system for<br />

commercial buildings: $300,000, $5 million and $10 million.<br />

Many projects don’t easily fit into the boxes, making owners choose<br />

between a less-desirable piecemeal investment over time or potentially<br />

biting off more than they can chew.<br />

“So there’s this kind of dichotomy of being too small to be worth<br />

the trouble for tax credits, and being too big and having to stay under<br />

a threshold,” Beman said.<br />

Low-end credit caps are more generous in nearby states: South<br />

Carolina’s is $1 million; Alabama’s is $5 million; and North Carolina’s<br />

is $15 million.<br />

Augusta businessman and philanthropist Clay Boardman, best<br />

26 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

PROFILES IN PRESERVATION<br />

MILLER THEATER<br />

708 Broad St.<br />

Mark Donahue, president of Peach Contractors, stands at 448 Greene St., a<br />

historic Victorian-era estate his company renovated into 10 apartment units.<br />

known for rehabilitating the long-vacant Enterprise Mill into a successful<br />

mixed-use property and purchasing the historic Houghton<br />

School building for Heritage Academy, is a partner in the company<br />

that owns the Marion Building.<br />

Boardman said the building has been under contract to sell at least<br />

four times during the past five years. Each time the deal fell though<br />

after the prospective developer ran a pro forma to rehabilitate the<br />

10-story mid-rise into an income-producing property.<br />

Even contributing the building at cost for an equity stake in the<br />

proposed developments wasn’t enough to sway investors.<br />

“I have many friends in (South Carolina) and elsewhere that want<br />

to invest in Augusta and they have visited many times,“ Boardman<br />

said. ”They simply can’t make the numbers work.”<br />

Augusta’s low-cost real estate market is a double-edged sword:<br />

Residents benefit from affordable prices, but investors have less<br />

incentive to take on the costly challenges of turning older buildings<br />

into livable residences.<br />

“If you want hip, cool, innovative developments in Augusta, the<br />

risks often don’t justify the potential reward. It’s just a fact,” he said.<br />

“I hate it because I love Augusta and stand ready to invest further, but<br />

given a choice, and a limited pool of investment funds, it can prove far<br />

smarter to invest elsewhere.”<br />

Donahue makes his projects work financially by seeking out rightsized<br />

properties and by acting as his own general contractor and<br />

The Miller Theater was one of the biggest victims of urban<br />

decay in Augusta during the 1980s – but few seemed to realize it<br />

until the historic theater reopened in grand style on Jan. 6, 2018.<br />

It was only then that people realized what they had been missing<br />

all those years; the Italian marble terrazzo, the black walnut<br />

millwork and the stellar acoustics that made the Miller one of the<br />

finest theaters in the Southeast.<br />

The Art Moderne-style venue Frank J. Miller opened in 1940 was<br />

the second-largest in the state, behind only Atlanta’s Fox Theatre.<br />

The Broad Street theater played host to scores of performances<br />

and hundreds of films from Hollywood’s golden era, including the<br />

world premiere of “The Three Faces of Eve” in 1957.<br />

Suburban multiplexes led to the Miller’s downfall and the venue<br />

closed for good in 1984, starting a two-decade period of dilapidation<br />

that went unabated until 2005 when Augusta philanthropist<br />

Peter Knox IV purchased and mothballed the building to stave off<br />

further damage.<br />

Three years later the theater and an adjoining building – the former<br />

Cullum’s department store – were offered as a permanent home to<br />

the Augusta Symphony through a $23 million community campaign<br />

that culminated with the theater’s historic reopening in 2018.<br />

With the exception of state and federal historic tax credits and<br />

$5.1 million from a special purpose local option sales tax package,<br />

the money was contributed from individuals, corporations and<br />

foundations.<br />

It remains Augusta’s largest historic preservation project to date.<br />

A 2009 photo of the Miller Theater’s lobby shows its dilapidation<br />

from more than three decades of neglect.<br />

[FILE PHOTOS/THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

<strong>1736</strong>magazine.com | 27

PROFILES IN PRESERVATION<br />

A photo from 2018 shows the Trinity CME Church building sitting in<br />

the middle of Taylor Street on its way to a new site. [FILE PHOTOS/<br />

THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

TRINITY CHRISTIAN METHODIST<br />

EPISCOPAL CHURCH<br />

731 Taylor St.<br />

Moving a 400-ton church building from the 19th century 250<br />

feet onto a new foundation is not an ordinary undertaking. But the<br />

Trinity CME church on Taylor Street is not your ordinary building.<br />

The 130-year-old church, known as “Mother Trinity,” is the birthplace<br />

of the CME denomination. And before it was hoisted on steel girders<br />

and rolled on special dollies to its new location near the Augusta<br />

Canal’s third level in June 2018, it was destined for the wrecking ball.<br />

The historic church where a young James Brown learned to play<br />

the piano was targeted for demolition for nearly 20 years under a<br />

plan to remediate the soil underneath that was contaminated by<br />

the century-long operation of a nearby Atlanta Gas Light plant.<br />

An Augusta Canal Authority-negotiated plan enabled the church<br />

built by former slaves in the 1890s to move to its new location,<br />

enabling the cleanup of coal tar to resume while giving the old<br />

building new life as a community center, arts venue or trail head.<br />

Earlier remediation phases leveled all buildings in the area<br />

except the church, whose congregation relocated to a new building<br />

on Glenn Hills Drive.<br />

“What a glorious day it is,” said the Rev. Herman “Skip” Mason,<br />

pastor of Augusta’s new Trinity CME, as he watched the old church<br />

slowly roll across Taylor Street to its new site on June 13, 2018. “We<br />

give glory to God, but we also must give thanks to the Augusta<br />

Canal Authority.”<br />

Broken glass and other debris litter the floor near the banister at<br />

Trinity CME Church in this photo from 2014.<br />

property manager. Master carpenter Mitch Kirkendohl manages<br />

Donahue’s construction crews while office manager Michele<br />

Meehan oversees the leasing.<br />

“I wouldn’t be able to do these things without them,” Donahue<br />

said.<br />

Until Augusta reaches a point where demand for downtown<br />

real estate creates greater yields for investors, King said the city’s<br />

best chance for redeveloping vacant historic properties lies with<br />

end-user occupants and long-term investors with a soft spot for<br />

preservation.<br />

“I think the whole thing behind it is people have so much instant<br />

gratification these days – that people aren’t willing to wait until<br />

things are profitable,” he said. “You could do a (large project) and<br />

it might be a 15-year payback instead of a five-year payback. So<br />

there has to be an intention behind the economics of it; there has<br />

to be a passion as well.”<br />

WHEN PRESERVATION AND PROGRESS COLLIDE<br />

Few locals seemed to notice the unassuming brick building<br />

that’s been crumbling for decades at the northwest corner of the<br />

Augusta Common.<br />

That is, until the building’s current owner – Augusta-based<br />

Azalea Investments – discovered it was in danger of collapsing<br />

and petitioned for demolition last fall.<br />

Suddenly, many people became highly interested in the<br />

building.<br />

The long-vacant property quickly appeared on Historic<br />

Augusta’s <strong>2020</strong> Endangered Properties list.<br />

Research determined the building at 840 Reynolds St. had a<br />

peculiar origin: It was constructed at the turn-of-the-century as<br />

the Augusta Trunk Factory for Mary Cleckley, making the twostory<br />

structure the site of one of the city’s earliest woman-owned<br />

enterprises.<br />

“She had a very successful business at a time when very few<br />

women had businesses and very few women built buildings of<br />

their own,” Montgomery said of Cleckley during a November<br />

press conference highlighting the list.<br />

Azalea soon found itself in a place no real estate developer wants<br />

to be: owning a building whose cultural value exceeds its financial<br />

worth.<br />

The Augusta Historic Preservation Commission generally<br />

frowns on the demolition of historic buildings in the three citydesignated<br />

districts, except in extreme cases.<br />

“We know what the commission will say, in a way,” said Erik<br />

Engle, a senior planner with the Augusta Planning Commission<br />

who serves as staff liaison to the 12-member preservation board.<br />

“We really do try to work with (owners) so if there is an absolute<br />

need for demolition, we know why.”<br />

The preservation commission has historically encouraged<br />

owners to explore ways to save at least parts of structurally compromised<br />

buildings, as it has in the case of 840 Reynolds.<br />

“We’re always trying to figure out how to work with whatever<br />

their pro forma says to find out how to incorporate (the historic)<br />

elements into the site,” Engle said. “Like, why not try to stabilize<br />

two of the facades and incorporate that into the design somehow.”<br />

When demolition is the only option, city ordinances require<br />

owners submit a redevelopment plan to ensure properties<br />

do not become vacant lots in perpetuity. The “certificate of<br />

28 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

Mark Donahue, from right, president of Peach<br />

Contractors, stands with office manager<br />

Michele Meehan and his master carpenter<br />

Mitch Kirkendohl at 448 Greene St., a historic<br />

Victorian-era estate his company renovated<br />

into 10 apartment units.<br />

appropriateness” process also strives<br />

to verify replacement structures<br />

will aesthetically conform to its<br />

surroundings.<br />

Azalea President Derek May said<br />

the firm is currently studying how it<br />

can redevelop the site while preserving<br />

elements of the 4,600-square-foot<br />

building, which was cordoned off and<br />

put under 24-hour security after it was<br />

condemned in September.<br />

The two-story, 120-year-old<br />

building fronts Reynolds Street and<br />

is book-ended by the Common and<br />

the former parking lot of the old Belk<br />

department store. Its south end abuts<br />

841 Broad St., a Sprint Food Storesowned<br />

building that housed its Metro<br />

Market convenience store until it closed<br />

in early 2018.<br />

Azalea’s initial plan was to renovate<br />

840 Reynolds as a pub for Riverwatch<br />

Brewery. The plan fell through after<br />

Azalea’s contractors discovered renovation<br />

work could trigger a collapse.<br />

“When we determined it was just in<br />

much worse shape than we thought,<br />

the first thing we did was go to the city<br />

and tell them we thought the building<br />

was a public-safety hazard, and they<br />

agreed,” said May, whose firm acquired<br />

the property from the estate of Augusta<br />

businessman Julian Osbon in 2016.<br />

May said it’s possible parts of the<br />

rectangular-shaped structure could<br />

be incorporated into a multi-family<br />

project Azalea is pursuing on adjacent<br />

lots at the corner of Ninth and Reynolds<br />

streets, the former site of the Augusta<br />

Police Department.<br />

The Great Depression-era police<br />

building – which was severely damaged<br />

and had no roof when an Azaleaaffiliated<br />

entity purchased it in 2016<br />

– was demolished in early 2017.<br />

Azalea, which is owned by the<br />

children of former Augusta Chronicle<br />

owner William S. Morris III, previously<br />

had plans to build a Marriott-branded<br />

hotel on the old police station site. May<br />

said the firm has since pivoted to a<br />

multi-family concept because demand<br />

for downtown apartments is greater<br />

than hotel rooms.<br />

He said the company’s owners – all<br />

native Augustans – are committed to<br />

historic preservation and are evaluating<br />

their options for 840 Reynolds and the<br />

adjacent vacant lots.<br />

“We don’t have a firm plan yet,” May<br />

said. “It could be something completely<br />

different than what we originally had in<br />

mind.”<br />

He said making the old Trunk<br />

Factory building a component of a<br />

new development – similar to the way<br />

city officials incorporated the former<br />

Harrison family warehouse into the<br />

Augusta Convention Center five years<br />

ago – could make partial restoration<br />

financially feasible.<br />

But rehabilitating the condemned<br />

building in its current condition as a<br />

stand-alone development would be a<br />

long-term money loser based on current<br />

Augusta lease rates, May said.<br />

Historic preservationists and developers<br />

often clash, but May describes<br />

discussions regarding the Trunk<br />

Factory building as a “cordial process.”<br />

“All of these groups have been great<br />

to work with,” May said. “I compliment<br />

the folks we’ve worked with on<br />

this. They have been very open and<br />

accommodating.”<br />

Two decades into its resurgence,<br />

downtown Augusta finds itself at an<br />

odd juncture.<br />

Public officials, developers and<br />

the general public universally agree<br />

increasing the number of people living<br />

downtown is the linchpin to boosting<br />

commerce and revitalization in the<br />

urban core.<br />

But the supply of downtown residential<br />

units is still below the demand, as<br />

evidenced by the Augusta Downtown<br />

Development Authority’s estimated<br />

98% occupancy rate for apartments in<br />

the central business district.<br />

Property owners, developers<br />

and commercial real estate brokers<br />

overwhelmingly agree many young<br />

professionals being drawn to Augusta’s<br />

military-fueled cybersecurity industry<br />

yearn for urban living.<br />

But they are wary of gambling on<br />

future employment projections, given<br />

the time and expense of rehabilitating<br />

historic buildings into office, business<br />

and apartment spaces – especially in a<br />

low-rate atmosphere.<br />

Economic development officials<br />

and business leaders acknowledge the<br />

buying and selling of downtown real<br />

estate is on a steep upward trajectory.<br />

But only a handful of transactions<br />

have yielded new developments. And<br />

the central business district’s inventory<br />

of vacant space, which ranges from<br />

move-in ready to the severely dilapidated,<br />

exceeds 1 million square feet – a<br />

space roughly the size of Augusta Mall.<br />

THE ILLUSIVE TIPPING POINT<br />

Is the wait for downtown Augusta’s<br />

boom getting in the way of the boom?<br />

Many of downtown’s long-vacant<br />

historic properties sit idle, even as<br />

plans are being drawn up for newlyconstructed<br />

office, retail and residential<br />

buildings, such as Ivey Development’s<br />

30 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

An artist rendering depicts fully renovated buildings at the<br />

northwest corner of Ninth and Telfair streets. All properties<br />

depicted are for sale and 90 percent vacant. [SPECIAL/<br />

BLANCHARD & CALHOUN COMMERCIAL CORP.]<br />

155-unit Millhouse Station, Azalea<br />

Investments’ proposed multi-family<br />

midrise and the on-again off-again<br />

Riverfront at the Depot mixed-use<br />

complex.<br />

There appears to be no firm date on<br />

the economic tipping point that will<br />

coax property owners and developers<br />

into rehabilitating historic buildings.<br />

But the floodgates of preservation<br />

activity likely won’t open until demand<br />

for space – particularly residential –<br />

starts pushing Augusta’s rental rates<br />

toward parity with other Southeastern<br />

markets.<br />

“I am happy that housing costs are<br />

very low in Augusta – it helps many<br />

people,” Boardman says. “But, it comes<br />

at a price – fewer new developments,<br />

fewer higher risk developments, fewer<br />

housing choices.”<br />

King, the architect, said he understands<br />

the conundrum owners and<br />

investors face on historic renovation<br />

projects. Until the stars align, he<br />

believes the slow-but-steady growth<br />

that has typified redevelopment activity<br />

in the city’s urban core during the<br />

past several years will persist.<br />

Unless someone is willing to take a<br />

The orange glow of the setting sun is reflected off the Lamar Building, right, and the Marion<br />

building, left, in downtown Augusta. Bringing the old buildings up to modern codes is too costly<br />

for many investors at current lease rates. [FILE/THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

major leap of faith.<br />

“I think a few people own a lot of<br />

the buildings downtown and they’re<br />

waiting for the right tenant with big<br />

enough pockets to say, ’I’ll pay for XYZ<br />

renovation to occur,’ ” he said. “And<br />

maybe those tenants are waiting for<br />

the population density of downtown<br />

to grow up, which is waiting on the<br />

apartments to get more people living<br />

downtown.<br />

“You get to a certain number, and<br />

that sparks the need for a grocery<br />

store,” King says. “In my opinion, you<br />

hit that number and the new growth<br />

will begin to get exponential.”<br />

<strong>1736</strong>magazine.com | 31

G. Lloyd Preacher’s architectural<br />

career was launched in 1911<br />

after winning a competition<br />

to design the Augusta Fire<br />

Department headquarters,<br />

a building that now holds<br />

apartments and The Marbury<br />

Center meeting hall.<br />

[FILE/THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE]<br />

32 | <strong>1736</strong>magazine.com

By DAMON CLINE<br />

Augusta’s<br />

ARCHITECT<br />

Augusta was very much an architectural<br />

blank slate in the early 20th<br />

century.<br />

Much of the city center had been<br />

destroyed by the Great Fire of 1916. Wide<br />

swaths of the countryside were opening up<br />

for development. And economic prosperity<br />

was ushering in the decade that would come<br />

to be known as the Roaring Twenties.<br />

It was during this era that one of the most<br />

famous architects to ever work in Augusta –<br />

G. Lloyd Preacher – would make a mark that<br />

can still be seen today.<br />

The creative force behind hundreds of<br />

buildings throughout the Southeast cut his<br />

teeth in Augusta by working on such structures<br />

as the Imperial Theatre, the Marion<br />

Building and the Houghton School.<br />

Noted local historian Ed Cashin wrote<br />

in his book, “The Story of Augusta,” that<br />

Preacher “more than anyone else left his<br />

mark on modern Augusta.”<br />

Preacher was born 60 miles southeast<br />

of Augusta in the Allendale County town<br />

of Fairfax, S.C. He moved to Augusta to<br />

work as a draftsman at Lombard Iron Works<br />

shortly after graduating with an engineering<br />

degree from Clemson College in 1904.<br />

Marrying a local girl, Fannie McDaniel, in<br />

1905 would help keep Preacher in Augusta<br />

for the next 15 years, resulting in the creation<br />

of some of the city’s most recognizable<br />

buildings.<br />

He was working as a civil engineer in 1909<br />

when he won the contest to design the city’s<br />

fire department headquarters on the 1200<br />

block of Broad Street. The three-story building<br />

now houses apartment units on the upper<br />

floors and the Marbury Center event space at<br />

the ground level.<br />

Preacher followed up the success by designing<br />

Harlem, Ga.’s Masonic Lodge building in<br />

1911 and by collaborating with W.L. Stoddart<br />

on downtown Augusta’s Marion Building (constructed<br />

as the Chronicle Building in 1912) and<br />

GEOFFREY LLOYD PREACHER<br />

Born: May 11, 1882; Fairfax, S.C.<br />

Died: June 17, 1972; Atlanta<br />

Alma mater: Clemson University (then Clemson College),<br />

engineering and architecture<br />

Family: Wife, Fannie; sons, Geoffrey Jr. and Jack<br />

Years active: 1904-1954<br />

Notable Augusta buildings:<br />

• Partridge Inn (first expansion), 1907<br />

• Marbury Center (originally Augusta Fire Department headquarters), 1909<br />

• Marion Building (originally the Chronicle Building), 1912*<br />

• Lamar Building (originally the Empire Life Insurance Building), 1913*<br />

• James Hotel (originally the Plaza Hotel), 1914**<br />

• University Hospital, 1915**<br />

• Modjeska Theater, 1916<br />

• Heritage Academy (originally the Houghton School), 1916<br />

• Cobb House (originally the Shirley Hotel), 1916<br />

• News Building (originally the Augusta Herald building), 1917<br />

• Imperial Theatre, 1917<br />

• Tubman Education Center (originally Tubman High School), 1918<br />

• Rialto Theater, 1918**<br />

• Lenox Theater, 1921**<br />

• Richmond Summit (originally the Richmond Hotel), 1923<br />

* Co-designed<br />

** Demolished<br />

Source: Staff research<br />

<strong>1736</strong>magazine.com | 33

The G. Lloyd Preacher-designed Houghton School opened in 1916 when the previous school named for Augusta businessman John W.<br />

Houghton was destroyed by Augusta’s great fire. The building now houses the Heritage Academy private school. [FILE/THE AUGUSTA<br />

CHRONICLE]<br />

the Lamar Building (built as the Empire<br />

Life Insurance Building in 1913). The<br />

latter would hold the title of the city’s<br />

tallest structure for more than a halfcentury.<br />

After being commissioned to<br />

design University Hospital and the<br />

Lincoln County Courthouse, both in<br />

1915, Preacher embarked on a string<br />

of theater projects in downtown<br />

Augusta, including the Modjeska in<br />

1916, the Imperial in 1917 (originally<br />

the Wells Theater) and the Lenox in<br />

1921. The Lenox – condemned and<br />

demolished in 1978 – was regarded as<br />

one of the finest black movie theaters<br />

in the segregation-era South.<br />

Other notable projects from this<br />

period include the Cobb House (originally<br />

the Shirley Hotel), the Richmond<br />

Summit (built as the Richmond<br />

Hotel) and numerous private homes<br />

in the Summerville neighborhood.<br />

Influenced by the Chicago school<br />

of architecture, Preacher’s commercial<br />

buildings often relied on<br />

elaborate ornamentation and lightcolored<br />

brick to soften sharp edges.<br />

By the early 1920s, Atlanta had<br />

The Chronicle Building was constructed<br />

in 1914 and was gutted by the Great<br />

Fire of 1916. It was renamed the Marion<br />

Building when it reopened in 1922.<br />

[SPECIAL]<br />

become such a steady source of<br />

work that Preacher decided to live<br />