You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

| DISCOVER<br />

in plain<br />

sight<br />

BY CHUCK GRAHAM<br />

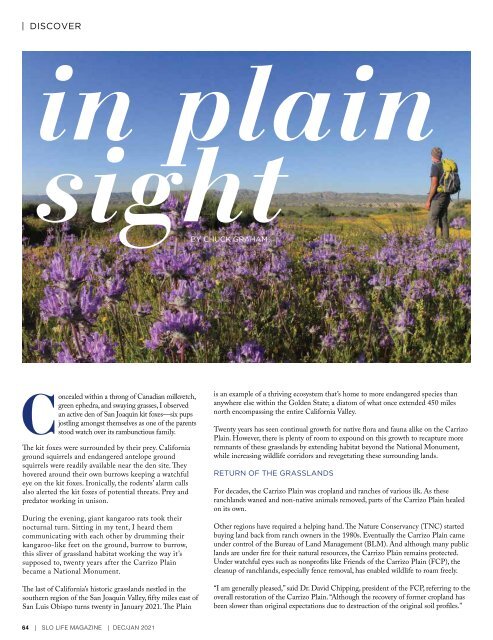

Concealed within a throng of Canadian milkvetch,<br />

green ephedra, and swaying grasses, I observed<br />

an active den of San Joaquin kit foxes—six pups<br />

jostling amongst themselves as one of the parents<br />

stood watch over its rambunctious family.<br />

The kit foxes were surrounded by their prey. California<br />

ground squirrels and endangered antelope ground<br />

squirrels were readily available near the den site. They<br />

hovered around their own burrows keeping a watchful<br />

eye on the kit foxes. Ironically, the rodents’ alarm calls<br />

also alerted the kit foxes of potential threats. Prey and<br />

predator working in unison.<br />

During the evening, giant kangaroo rats took their<br />

nocturnal turn. Sitting in my tent, I heard them<br />

communicating with each other by drumming their<br />

kangaroo-like feet on the ground, burrow to burrow,<br />

this sliver of grassland habitat working the way it’s<br />

supposed to, twenty years after the Carrizo Plain<br />

became a National Monument.<br />

The last of California’s historic grasslands nestled in the<br />

southern region of the San Joaquin Valley, fifty miles east of<br />

San Luis Obispo turns twenty in <strong>Jan</strong>uary <strong>20</strong><strong>21</strong>. The Plain<br />

is an example of a thriving ecosystem that’s home to more endangered species than<br />

anywhere else within the Golden State; a diatom of what once extended 450 miles<br />

north encompassing the entire California Valley.<br />

Twenty years has seen continual growth for native flora and fauna alike on the Carrizo<br />

Plain. However, there is plenty of room to expound on this growth to recapture more<br />

remnants of these grasslands by extending habitat beyond the National Monument,<br />

while increasing wildlife corridors and revegetating these surrounding lands.<br />

RETURN OF THE GRASSLANDS<br />

For decades, the Carrizo Plain was cropland and ranches of various ilk. As these<br />

ranchlands waned and non-native animals removed, parts of the Carrizo Plain healed<br />

on its own.<br />

Other regions have required a helping hand. The Nature Conservancy (TNC) started<br />

buying land back from ranch owners in the 1980s. Eventually the Carrizo Plain came<br />

under control of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). And although many public<br />

lands are under fire for their natural resources, the Carrizo Plain remains protected.<br />

Under watchful eyes such as nonprofits like Friends of the Carrizo Plain (FCP), the<br />

cleanup of ranchlands, especially fence removal, has enabled wildlife to roam freely.<br />

“I am generally pleased,” said Dr. David Chipping, president of the FCP, referring to the<br />

overall restoration of the Carrizo Plain. “Although the recovery of former cropland has<br />

been slower than original expectations due to destruction of the original soil profiles.”<br />

64 | <strong>SLO</strong> <strong>LIFE</strong> MAGAZINE | DEC/JAN <strong>20</strong><strong>21</strong>