Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

30<br />

The <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

Medieval Feminism?<br />

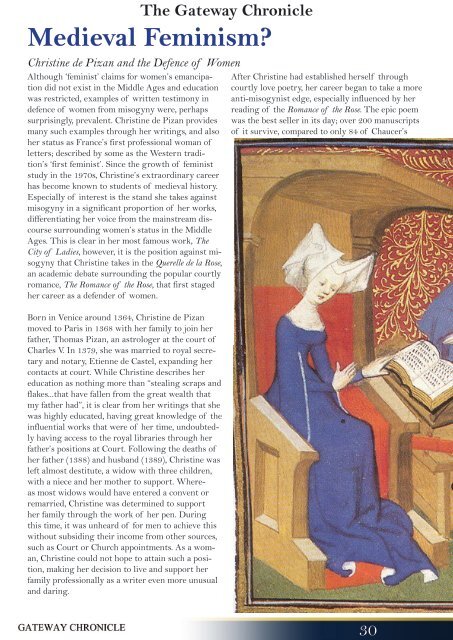

Christine de Pizan and the Defence of Women<br />

Although ‘feminist’ claims for women’s emancipation<br />

did not exist in the Middle Ages and education<br />

was restricted, examples of written testimony in<br />

defence of women from misogyny were, perhaps<br />

surprisingly, prevalent. Christine de Pizan provides<br />

many such examples through her writings, and also<br />

her status as France’s first professional woman of<br />

letters; described by some as the Western tradition’s<br />

‘first feminist’. Since the growth of feminist<br />

study in the 1970s, Christine’s extraordinary career<br />

has become known to students of medieval history.<br />

Especially of interest is the stand she takes against<br />

misogyny in a significant proportion of her works,<br />

differentiating her voice from the mainstream discourse<br />

surrounding women’s status in the Middle<br />

Ages. This is clear in her most famous work, The<br />

City of Ladies, however, it is the position against misogyny<br />

that Christine takes in the Querelle de la Rose,<br />

an academic debate surrounding the popular courtly<br />

romance, The Romance of the Rose, that first staged<br />

her career as a defender of women.<br />

Born in Venice around 1364, Christine de Pizan<br />

moved to Paris in 1368 with her family to join her<br />

father, Thomas Pizan, an astrologer at the court of<br />

Charles V. In 1379, she was married to royal secretary<br />

and notary, Etienne de Castel, expanding her<br />

contacts at court. While Christine describes her<br />

education as nothing more than “stealing scraps and<br />

flakes...that have fallen from the great wealth that<br />

my father had”, it is clear from her writings that she<br />

was highly educated, having great knowledge of the<br />

influential works that were of her time, undoubtedly<br />

having access to the royal libraries through her<br />

father’s positions at Court. Following the deaths of<br />

her father (1388) and husband (1389), Christine was<br />

left almost destitute, a widow with three children,<br />

with a niece and her mother to support. Whereas<br />

most widows would have entered a convent or<br />

remarried, Christine was determined to support<br />

her family through the work of her pen. During<br />

this time, it was unheard of for men to achieve this<br />

without subsiding their income from other sources,<br />

such as Court or Church appointments. As a woman,<br />

Christine could not hope to attain such a position,<br />

making her decision to live and support her<br />

family professionally as a writer even more unusual<br />

and daring.<br />

After Christine had established herself through<br />

courtly love poetry, her career began to take a more<br />

anti-misogynist edge, especially influenced by her<br />

reading of the Romance of the Rose. The epic poem<br />

was the best seller in its day; over 200 manuscripts<br />

of it survive, compared to only 84 of Chaucer’s