Grey Bruce Boomers Fall 2021

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

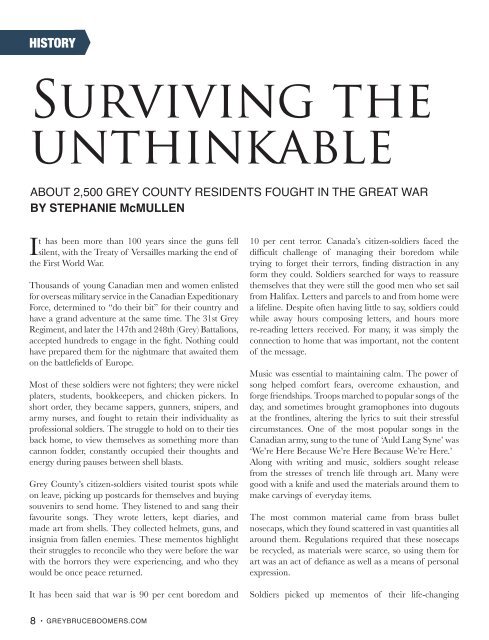

HISTORY<br />

Surviving the<br />

unthinkable<br />

ABOUT 2,500 GREY COUNTY RESIDENTS FOUGHT IN THE GREAT WAR<br />

BY STEPHANIE McMULLEN<br />

It has been more than 100 years since the guns fell<br />

silent, with the Treaty of Versailles marking the end of<br />

the First World War.<br />

Thousands of young Canadian men and women enlisted<br />

for overseas military service in the Canadian Expeditionary<br />

Force, determined to “do their bit” for their country and<br />

have a grand adventure at the same time. The 31st <strong>Grey</strong><br />

Regiment, and later the 147th and 248th (<strong>Grey</strong>) Battalions,<br />

accepted hundreds to engage in the fight. Nothing could<br />

have prepared them for the nightmare that awaited them<br />

on the battlefields of Europe.<br />

Most of these soldiers were not fighters; they were nickel<br />

platers, students, bookkeepers, and chicken pickers. In<br />

short order, they became sappers, gunners, snipers, and<br />

army nurses, and fought to retain their individuality as<br />

professional soldiers. The struggle to hold on to their ties<br />

back home, to view themselves as something more than<br />

cannon fodder, constantly occupied their thoughts and<br />

energy during pauses between shell blasts.<br />

<strong>Grey</strong> County’s citizen-soldiers visited tourist spots while<br />

on leave, picking up postcards for themselves and buying<br />

souvenirs to send home. They listened to and sang their<br />

favourite songs. They wrote letters, kept diaries, and<br />

made art from shells. They collected helmets, guns, and<br />

insignia from fallen enemies. These mementos highlight<br />

their struggles to reconcile who they were before the war<br />

with the horrors they were experiencing, and who they<br />

would be once peace returned.<br />

It has been said that war is 90 per cent boredom and<br />

10 per cent terror. Canada’s citizen-soldiers faced the<br />

difficult challenge of managing their boredom while<br />

trying to forget their terrors, finding distraction in any<br />

form they could. Soldiers searched for ways to reassure<br />

themselves that they were still the good men who set sail<br />

from Halifax. Letters and parcels to and from home were<br />

a lifeline. Despite often having little to say, soldiers could<br />

while away hours composing letters, and hours more<br />

re-reading letters received. For many, it was simply the<br />

connection to home that was important, not the content<br />

of the message.<br />

Music was essential to maintaining calm. The power of<br />

song helped comfort fears, overcome exhaustion, and<br />

forge friendships. Troops marched to popular songs of the<br />

day, and sometimes brought gramophones into dugouts<br />

at the frontlines, altering the lyrics to suit their stressful<br />

circumstances. One of the most popular songs in the<br />

Canadian army, sung to the tune of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ was<br />

‘We’re Here Because We’re Here Because We’re Here.’<br />

Along with writing and music, soldiers sought release<br />

from the stresses of trench life through art. Many were<br />

good with a knife and used the materials around them to<br />

make carvings of everyday items.<br />

The most common material came from brass bullet<br />

nosecaps, which they found scattered in vast quantities all<br />

around them. Regulations required that these nosecaps<br />

be recycled, as materials were scarce, so using them for<br />

art was an act of defiance as well as a means of personal<br />

expression.<br />

Soldiers picked up mementos of their life-changing<br />

8 • GREYBRUCEBOOMERS.COM