1956 +The Crimson White: Legacy Edition, October 2021

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 21, <strong>2021</strong><br />

VOLUME CXXVIII | ISSUE IV<br />

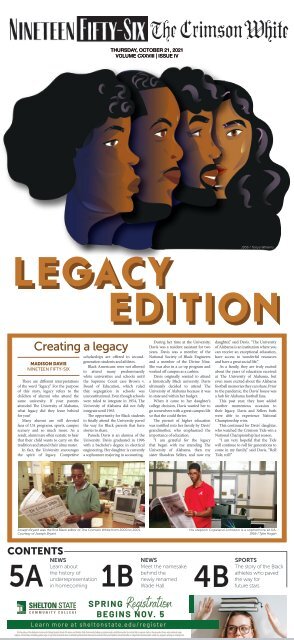

<strong>1956</strong> / Tonya Williams<br />

LEGACY<br />

EDITION<br />

Creating a legacy<br />

MADISON DAVIS<br />

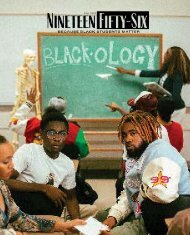

NINETEEN FIFTY-SIX<br />

There are different interpretations<br />

of the word “legacy.” For the purpose<br />

of this story, legacy refers to the<br />

children of alumni who attend the<br />

same university. If your parents<br />

attended The University of Alabama,<br />

what legacy did they leave behind<br />

for you?<br />

Many alumni are still devoted<br />

fans of UA programs, sports, campus<br />

scenery and so much more. As a<br />

result, alumni are often ecstatic to hear<br />

that their child wants to carry on the<br />

tradition and attend their alma mater.<br />

In fact, the University encourages<br />

the spirit of legacy. Competitve<br />

scholarships are offered to secondgeneration<br />

students and athletes.<br />

Black Americans were not allowed<br />

to attend many predominantly<br />

white universities and schools until<br />

the Supreme Court case Brown v.<br />

Board of Education, which ruled<br />

that segregation in schools was<br />

unconstitutional. Even though schools<br />

were ruled to integrate in 1954, The<br />

University of Alabama did not fully<br />

integrate until 1963.<br />

The opportunity for Black students<br />

to finally attend the University paved<br />

the way for Black parents that have<br />

stories to share.<br />

Pamela Davis is an alumna of the<br />

University. Davis graduated in 1996<br />

with a bachelor's degree in electrical<br />

engineering. Her daughter is currently<br />

a sophomore majoring in accounting.<br />

During her time at the University,<br />

Davis was a resident assistant for two<br />

years. Davis was a member of the<br />

National Society of Black Engineers<br />

and a member of the Divine Nine.<br />

She was also in a co-op program and<br />

worked off campus as a cashier.<br />

Davis originally wanted to attend<br />

a historically Black university. Davis<br />

ultimately decided to attend The<br />

University of Alabama because it was<br />

in state and within her budget.<br />

When it came to her daughter’s<br />

college decision, Davis wanted her to<br />

go somewhere with a great campus life<br />

so that she could thrive.<br />

The pursuit of higher education<br />

was instilled into her family by Davis’<br />

grandmother, who emphasized the<br />

importance of education.<br />

“I am grateful for the legacy<br />

that began with me attending The<br />

University of Alabama, then my<br />

sister Shandrea Sellers, and now my<br />

daughter,” said Davis. “The University<br />

of Alabama is an institution where you<br />

can receive an exceptional education,<br />

have access to wonderful resources<br />

and have a great social life.”<br />

As a family, they are truly excited<br />

about the years of education received<br />

at The University of Alabama, but<br />

even more excited about the Alabama<br />

football memories they can share. Prior<br />

to the pandemic, the Davis’ house was<br />

a hub for Alabama football fans.<br />

This past year, they have added<br />

another momentous occasion to<br />

their legacy. Davis and Sellers both<br />

were able to experience National<br />

Championship wins.<br />

This continued for Davis’ daughter,<br />

who watched the <strong>Crimson</strong> Tide win a<br />

National Championship last season.<br />

“I am very hopeful that the Tide<br />

will continue to roll for generations to<br />

come in my family,” said Davis. “Roll<br />

Tide, roll!”<br />

Joseph Bryant was the first Black editor of The <strong>Crimson</strong> <strong>White</strong> from 2000 to 2001.<br />

Courtesy of Joseph Bryant<br />

His stepson Copeland Johnson is a sophomore at UA.<br />

<strong>1956</strong> / Tyler Hogan<br />

CONTENTS<br />

5A<br />

Learn<br />

NEWS<br />

about<br />

the history of<br />

underrepresentation<br />

in homecoming<br />

1B<br />

NEWS<br />

Meet the namesake<br />

behind the<br />

newly renamed<br />

Wade Hall<br />

SPRING Registration<br />

BEGINS NOV. 5<br />

Learn more at sheltonstate.edu/register<br />

It is the policy of the Alabama Community College System Board of Trustees and Shelton State Community College, a postsecondary institution under its control, that no person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin,<br />

religion, marital status, disability, gender, age, or any other protected class as defined by federal and state law, be excluded from participation, denied benefits, or subjected to discrimination under any program, activity, or employment.<br />

4B<br />

SPORTS<br />

The story of the Black<br />

athletes who paved<br />

the way for<br />

future stars

2A<br />

NINETEEN FIFTY-SIX<br />

editor-in-chief Tionna Taite<br />

managing editor<br />

engagement editor<br />

photography editor<br />

visuals editor<br />

features & experiences<br />

editor<br />

assistant engagement<br />

editor<br />

assistant photography<br />

editor<br />

THE CRIMSON WHITE<br />

editor-in-chief<br />

managing editor<br />

engagement editor<br />

chief copy editor<br />

opinions editor<br />

news editor<br />

assistant news editor<br />

culture editor<br />

assistant culture editor<br />

sports editor<br />

assistant sports editor<br />

chief page editor<br />

chief graphics editor<br />

photo editor<br />

assistant photo editor<br />

multimedia editor<br />

Nickell Grant<br />

Madison Davis<br />

Tyler Hogan<br />

Ashton Jah<br />

Ashlee Woods<br />

Jolencia Jones<br />

Madison Carmouche<br />

Keely Brewer<br />

editor@cw.ua.edu<br />

Bhavana Ravala<br />

managingeditor@cw.ua.edu<br />

Garrett Kennedy<br />

engagement@cw.ua.edu<br />

Jack Maurer<br />

Ava Fisher<br />

letters@cw.ua.edu<br />

Zach Johnson<br />

newsdesk@cw.ua.edu<br />

Isabel Hope<br />

Jeffrey Kelly<br />

culture@cw.ua.edu<br />

Annabelle Blomeley<br />

Ashlee Woods<br />

sports@cw.ua.edu<br />

Robert Cortez<br />

Pearl Langley<br />

Victoria Buckley<br />

Lexi Hall<br />

David Gray<br />

Alex Miller<br />

ADVERTISING STAFF<br />

creative services Alyssa Sons<br />

The <strong>Crimson</strong> Wh is the community newspaper of<br />

The University of Alabama. The <strong>Crimson</strong> <strong>White</strong> is an<br />

editorially free newspaper produced by students.<br />

The University of Alabama cannot influence editorial<br />

decisions and editorial opinions are those of the<br />

editorial board and do not represent the official<br />

opinions of the University. Advertising offices of The<br />

<strong>Crimson</strong> <strong>White</strong> are in room 1014, Student Media<br />

Building, 414 Campus Drive East. The advertising<br />

mailing address is P.O. Box 870170, Tuscaloosa, AL<br />

35487.<br />

The <strong>Crimson</strong> <strong>White</strong>, Copyright © <strong>2021</strong><br />

by The <strong>Crimson</strong> <strong>White</strong>. The <strong>Crimson</strong> <strong>White</strong> is printed<br />

monthly, August through April by The University of<br />

Alabama, Student Media, Box 870170, Tuscaloosa, AL<br />

35487, Call 205-348-7257<br />

All material contained herein, except advertising or<br />

where indicated otherwise, is Copyright © <strong>2021</strong> by<br />

The <strong>Crimson</strong> <strong>White</strong> and protected under the “Work<br />

Made for Hire” and “Periodical Publication” categories<br />

of the U.S. copyright laws. Material herein may not be<br />

reprinted without the expressed, written permission<br />

of The <strong>Crimson</strong> <strong>White</strong>.<br />

Nov. 18 - Rumor <strong>Edition</strong><br />

Feb. 3 - Justice <strong>Edition</strong><br />

March 3 - Health <strong>Edition</strong><br />

April 21 - Environmental<br />

<strong>Edition</strong><br />

Tap in with CW!<br />

(We have an email newsletter now.)<br />

Subscribe to get our newsletter in your<br />

inbox on Monday and Thursday mornings.<br />

‘Before<br />

Stonewall’<br />

Safe Zone<br />

Student Lounge<br />

6 - 8PM<br />

21<br />

LEGACY<br />

<strong>October</strong> 21, <strong>2021</strong><br />

Tap in with <strong>1956</strong>!<br />

Check out their website and follow<br />

OCTOBER EVENTS<br />

Suicide<br />

26<br />

Prevention<br />

Training<br />

UA Student Center<br />

2408 10AM<br />

Keynote:<br />

Lydia X.Z.<br />

Brown<br />

Zoom<br />

6PM<br />

22 23<br />

26<br />

along on social media.<br />

Keep an eye out for their print<br />

edition in the spring.<br />

Career<br />

Coaching<br />

Zoom<br />

12PM<br />

UA vs.<br />

Tennessee<br />

Bryant-Denny<br />

Stadium<br />

6PM<br />

27<br />

25<br />

Fall Campus<br />

Assembly<br />

Bryant Conference<br />

Center 1:30PM<br />

Haunting at<br />

Gorgas<br />

Gorgas House<br />

Museum<br />

9AM - 4:30PM<br />

CW / Wesley Picard

LEGACY<br />

<strong>October</strong> 21, <strong>2021</strong><br />

3A<br />

CW File<br />

<strong>1956</strong> / Lyric Wisdom<br />

LETTERS FROM THE EDITORS<br />

KEELY BREWER<br />

The <strong>Crimson</strong> <strong>White</strong> and Nineteen<br />

Fifty-Six Magazine are the oldest and<br />

newest student publications on The<br />

University of Alabama campus. The CW<br />

has a 127-year-long history. Nineteen<br />

Fifty-Six is in its second year. Our<br />

histories differ, but the current staffs of<br />

both publications share the same goals:<br />

to leave a legacy of diversity and antiracism<br />

while advocating for all students.<br />

Under the guidance of some past<br />

editors, The CW has aligned itself with<br />

these values, but these values must be<br />

synonymous with our organization.<br />

Last year’s collaboration with Nineteen<br />

Fifty-Six was a step toward that goal,<br />

and this year’s edition is a continuation<br />

of what we hope will be a long-lasting<br />

and strong relationship with our<br />

sister publication.<br />

Since last year’s collaboration,<br />

The CW has published its first staff<br />

demographics report, which is publicly<br />

available on our website. We’ve hired<br />

our first race and identity reporters on<br />

the culture and news desks — which<br />

are funded through MASTHEAD, an<br />

alumni group supporting diversity<br />

in UA Student Media — and we’ve<br />

introduced systems to track the diversity<br />

of our sources. These are intended to be<br />

permanent fixtures at our organization.<br />

Nineteen Fifty-Six was founded<br />

with these principles in mind, and has<br />

already built a legacy on campus. This<br />

collaboration between our publications<br />

was created to recognize our own<br />

legacies and consider our trajectories.<br />

With consistency and intentionality,<br />

both publications can create a legacy<br />

worth being proud of.<br />

TIONNA TAITE<br />

The merging of these two publications<br />

signifies the progress that the University<br />

has made.<br />

This collaboration leaves behind a<br />

legacy for years to come. The notable<br />

Maya Angelou once said, “If you’re<br />

going to live, leave a legacy. Make a mark<br />

on the world that can’t be erased.” Maya<br />

Angelou left behind a legacy through her<br />

activism, poems and so much more. She<br />

is a prominent example of the impact<br />

both written and spoken words can have<br />

on society.<br />

This special edition dives into the<br />

numerous ways that alumni, students<br />

and public figures have created legacies<br />

at the University. As you read this special<br />

edition, you will see that there are many<br />

ways to leave behind a legacy.<br />

One way that I strive to do so is<br />

by creating a platform for students,<br />

particularly minority students, to have<br />

their voices heard. Another way that I<br />

strive to leave a legacy is by sharing the<br />

stories of those who may not have had<br />

the opportunity to do so themselves.<br />

Why is creating a legacy so important?<br />

Leaving behind a legacy allows those<br />

who come after you to have guidance<br />

and more opportunities. Some of you<br />

have already begun creating a legacy<br />

and just have not realized it. Some of<br />

you are the products of the legacy that<br />

your ancestors created. Truly, we all have<br />

a legacy to create and share.<br />

I am pleased to present this<br />

collaboration between Nineteen Fifty-<br />

Six and The <strong>Crimson</strong> <strong>White</strong>. I am certain<br />

that this special edition will educate and<br />

inspire you to leave behind a legacy of<br />

your own.<br />

JEFFREY KELLY<br />

THE CRIMSON WHITE<br />

“<strong>Legacy</strong>”<br />

By Jay-Z<br />

“<strong>Legacy</strong>” shares Jay-Z’s thoughts on<br />

what legacy he will leave his children.<br />

The lyrics are over an upbeat production,<br />

but they detail the various members of<br />

the Carter family and how they carried<br />

the name.<br />

“BLACK EFFECT”<br />

By The Carters<br />

Starting with advice from an older<br />

and wise woman, Beyoncé and Jay-Z lay<br />

out various aspects of Black history, such<br />

as the Chitlin Circuit and cornrows, to<br />

paint a picture of where Black people<br />

and our culture stand now. As our<br />

culture develops and shifts, it will always<br />

rely on aspects of our history.<br />

“Chaining Day”<br />

By J. Cole<br />

J. Cole explores the culture of people<br />

equating success to materialistic items<br />

such as expensive chains. He continues<br />

by explaining how such chains hinder<br />

individuals and prohibit them from<br />

leaving behind a true legacy that holds<br />

value.<br />

“If I Ruled the World”<br />

By Nas and Lauryn Hill<br />

Nas and Lauryn Hill dive into what<br />

they would do “if they ruled the world.”<br />

This song touches on the type of legacy<br />

The best songs to start your semester<br />

both Nas and Lauryn Hill would like to<br />

leave behind if they had all of the power<br />

to do so in the world. One topic the song<br />

touches on heavily is freeing people<br />

from the constraints of the world and<br />

revealing the power within the African<br />

diaspora.<br />

“What a Wonderful World”<br />

By Louis Armstrong<br />

As Louis Armstrong quaintly reflects<br />

on the aspects of this world and what<br />

makes it wonderful, he settles on the<br />

idea that it is people and the legacies<br />

they leave behind that allow the world to<br />

simply be “wonderful.”<br />

“BIGGER”<br />

By Beyoncé<br />

Beyoncé’s call to see that our purpose<br />

is bigger than our individual experience<br />

is woven into the lyrics of “BIGGER.”<br />

This song is one to pick you up off the<br />

ground and help you “step in your<br />

essence” and rise to meet your truest<br />

potential so that you may pass on what<br />

you have learned in this life.<br />

“I Am Blessed”<br />

By Nina Simone<br />

With “I Am Blessed,” a track from<br />

her third album, “Broadway-Blues-<br />

Ballads,” Nina Simone is in perfect<br />

form. Her dramatic silky vocals over the<br />

jazzy production have a cinematic “end<br />

credit” quality to them that feels serene.<br />

As she sings about “a love worth more<br />

than gold” her voice mimics the intense<br />

feelings of yearning and peace the lyrics<br />

discuss.<br />

“Good Golly, Miss Molly”<br />

By Little Richard<br />

Little Richard’s legacy in laying<br />

the foundations of rock ‘n’ roll is<br />

indisputable. With the simple swing<br />

beat and melodic piano work with a toetapping<br />

string bass to match, every aspect<br />

of modern rock music is foreshadowed<br />

in this track. Little Richard was just one<br />

of many Black artists who triumphed in<br />

the face of adversity and racism to create<br />

one of the most world-renowned and<br />

celebrated music genres of all time.<br />

“Turning Wheel”<br />

By Spellling<br />

“Turning Wheel” by Spellling, the<br />

Oakland artist otherwise known as<br />

Chrystia Cabrial, is the titular track<br />

of her third studio album. Its upbeat<br />

yet languid production makes for an<br />

ethereal track that resembles the work of<br />

'80s pop artist, Kate Bush.<br />

“Bad Blood”<br />

By Nao<br />

On Apple Music, English singer Nao<br />

describes her work as “wonky funk,” and<br />

with the track “Bad Blood” from her<br />

debut studio album, “For All We Know,”<br />

that definition seems to hold true. With<br />

the track, Nao’s angelic vocals skillfully<br />

dance between vocal registers as the<br />

bouncy funk production offers surprise<br />

after surprise until the track ends.<br />

“The Love I Need”<br />

By Girlhood<br />

In 2017, the London duo Girlhood<br />

was credited with making “some of<br />

London’s best new music” by Complex,<br />

and with their track “The Love I Need”<br />

from their 2020 album “Girlhood,” they<br />

continue to uphold that mantle.<br />

“Just the Two of Us”<br />

By Will Smith<br />

Will Smith dedicates this song to<br />

his first son Trey. It has a sample from<br />

a Bill Whithers song, also named, “Just<br />

the Two of Us” which is about a couple,<br />

but Smith’s rendition is about the love<br />

between father and son.<br />

“Mama”<br />

By Ray BLK<br />

From her debut album, “Empress,”<br />

BLK's single “Mama” is a smooth<br />

R&B track that interpolates 2Pac’s<br />

“Dear Mama." BLK’s poetic lyrics<br />

seem to perfectly match the midtempo<br />

production and the sentiment of love<br />

BLK seems to express in the song.

4A<br />

While many believe that colonization<br />

is something that happened centuries ago,<br />

the effects of colonization still run deep —<br />

and it’s apparent on college campuses.<br />

With almost no places left untouched,<br />

colonization has centered itself in<br />

academia, where it devalues people of<br />

color, ignores the history of colonialism<br />

and centers whiteness in everything that<br />

it does. Though it may be sparse, several<br />

departments and programs around The<br />

University of Alabama are working to<br />

decolonize their classrooms, mindsets and<br />

entire departments.<br />

Holly Horan, an assistant professor<br />

of anthropology and the chair of<br />

the Department of Anthropology’s<br />

Decolonization Committee, said she<br />

learned about the effects of marginalization<br />

on health and well-being early while being<br />

raised in a household with one white and<br />

one Puerto Rican parent.<br />

For her dissertation and her fieldwork<br />

in Puerto Rico, she studied the effect of<br />

perinatal stress on the timing of birth.<br />

“It was my lived experience of<br />

understanding what it’s like to be in a<br />

family with people of color and how<br />

they’re treated differently that has shaped<br />

my perspectives in this work,” Horan<br />

said. “From conversations that I had<br />

with my own mother about the history<br />

of the island, it was very clear to me<br />

the impact of colonization transcends<br />

geopolitical borders, generations and<br />

lived experiences.”<br />

During her research in Puerto Rico,<br />

Horan was deeply embedded in the<br />

country’s health care and perinatal<br />

care systems, which showcased to her<br />

the “explicit and insidious effects of<br />

colonization.” It was clear to her that “we<br />

do not live in a post-colonial world.”<br />

In the summer of 2020, during<br />

the pandemic and after the death of<br />

George Floyd, Horan and some of her<br />

anthropology colleagues at the University<br />

formed the Decolonization Committee<br />

to foster a department-level culture that<br />

emphasized the personal and collective<br />

responsibilities to fight oppression.<br />

“Decolonization is, at<br />

LEGACY<br />

<strong>October</strong> 21, <strong>2021</strong><br />

‘We do not live in a post-colonial world’:<br />

UA professors talk decolonization in academia<br />

ANNABELLE BLOMELEY & ETHAN HENRY<br />

THE CRIMSON WHITE<br />

minimum, a twofold process. The first is<br />

intention, and the second is action,” Horan<br />

said. “The intention of decolonization is<br />

to approach our work as anthropologists,<br />

being moral, being ethical and with a sense<br />

of justice, especially given the history of<br />

our discipline. The second piece of that is<br />

action. Decolonization is actively resisting<br />

oppressive systems in research, teaching<br />

and service. Decolonization is decentering<br />

standards and expectations that reinforce<br />

oppressive hierarchies.”<br />

On Friday, Nov. 5, the Decolonization<br />

Committee will hold a panel made up<br />

of students and professors to talk about<br />

decolonization, particularly for people<br />

who are unfamiliar with the topic.<br />

“Decolonization is also turning the<br />

lens inward and saying, ‘How do I, in my<br />

everyday interactions, attempt to decenter<br />

colonial ideologies and all that they<br />

represent?’” Horan said.<br />

Students are encouraged and welcome<br />

to support the decolonization process, but<br />

Horan said it’s important for professors,<br />

rather than students of color, to spearhead<br />

the department’s decolonization work.<br />

“Dismantling white supremacy, which<br />

is part of decolonization, should not<br />

have to be the work of people of color,”<br />

Horan said.<br />

Anthropology is one of the few<br />

departments on campus recognizing<br />

decolonization work, but professors in<br />

other departments are reexamining their<br />

colonial ties.<br />

Cindy Tekobbe, an Indigenous assistant<br />

professor in the Department of English,<br />

said decolonial theory takes a critical look<br />

at all western institutions built upon ceded<br />

land, including universities.<br />

They aim to take the focus away<br />

from the Eurocentrism that dominates<br />

Western academia. Tekobbe said there<br />

will need to be people who understand<br />

the model of Eurocentric knowledge<br />

and what it does to people.<br />

The values of these systems<br />

have created barriers<br />

that Tekobbe herself has been forced<br />

to confront.<br />

“My personal experience is that my<br />

value system is quite different from my<br />

colleagues’, and when we talk, we often<br />

miscommunicate because we’re not<br />

coming from the same place of knowing,”<br />

Tekobbe said. “For example, one of the<br />

things that’s really important is singleauthor<br />

scholarship. You’ve got to do the<br />

research yourself, and write it yourself, and<br />

produce it yourself, and put your name<br />

on it, but no one makes knowledge in<br />

a vacuum."<br />

Tekobbe, along with some of her<br />

colleagues, has attempted to create<br />

an Indigenous student organization.<br />

Indigenous students account for less than<br />

0.5% of the student population, and it is<br />

difficult to locate them because of the way<br />

they are registered.<br />

One of Tekkobbe’s colleagues, Heather<br />

Kopelson, an associate professor of history,<br />

also teaches classes that are informed by<br />

decolonial theory.<br />

Beyond the formation of an Indigenous<br />

student organization, Kopelson would<br />

like to see a Native studies or Indigenous<br />

studies minor added to the University’s<br />

course catalog.<br />

“I’ve been part of a group of faculty<br />

who have been talking about [adding<br />

an Indigenous studies minor], but it’s<br />

really hard to get a new program like that<br />

approved, especially because the question<br />

is always, ‘Well, can you show student<br />

interest?’” Kopelson said. “But I think one<br />

of the issues with indigenous studies in<br />

particular is that a lot of people have never<br />

even thought about it.”<br />

Kopelson said there have been small<br />

improvements in the Department<br />

of History in recent years. Other<br />

professors have incorporated Indigenous<br />

perspectives in their classrooms, and<br />

students have shown a renewed interest in<br />

Indigenous studies.<br />

Kopelson said she and<br />

Mairin Odle, an<br />

assistant professor in American studies<br />

who teaches Native American history,<br />

have full enrollment in their classes.<br />

Currently, Odle’s Native American<br />

studies course has 34 students, while<br />

Kopelson’s Native American history<br />

course has 38. Five years ago, the number<br />

of students in these classes barely reached<br />

double digits.<br />

Kopelson acknowledged the barriers<br />

that marginalized groups face when<br />

entering academic fields, but she wants<br />

students to know that they can ask for help.<br />

While decolonization seeks to eliminate<br />

these barriers, she said it’s important that<br />

students feel comfortable approaching<br />

faculty members for assistance.<br />

“In the history department, and in<br />

many others, the majority of faculty want<br />

students to ask for help and don’t see it<br />

as a weakness. And I think that’s a huge<br />

barrier in that the experiences of many<br />

marginalized groups have taught people<br />

that if they ask for help, that’s weakness,”<br />

Kopelson said.<br />

When colonial problems extend<br />

through the course material, it can be<br />

difficult for students to find help. This was<br />

the case for student Katherine Johnston,<br />

a junior majoring in kinesiology who<br />

identifies as Native American.<br />

“It’s hard to go into a class and hear<br />

somebody lecture to you about your own<br />

people’s history and for it to be completely<br />

inaccurate,” Johnston said. “As a Native<br />

student, I have had to take some history<br />

classes where the lessons taught on Native<br />

people are both very inaccurate and<br />

continue to feed into the ‘savage Indian’<br />

stereotype. It’s not just the teachers that<br />

feed that, but it’s the actual material that is<br />

being taught. It’s like we don’t matter. This<br />

is why the decolonization of education is<br />

so very important.”<br />

By recognizing the inherent effects of<br />

colonization and by<br />

decentering whiteness and<br />

colonial mindsets, students<br />

and faculty members<br />

alike can do their part to<br />

decolonize the Capstone.<br />

“There’s no way we can go back<br />

and fix the past. That is out of the<br />

question, but there’s always something<br />

that can be done to make the future<br />

better,” Horan said.<br />

Trailblazing footsteps<br />

<strong>1956</strong> / Ashton Jah<br />

RACHEL PARKER<br />

NINETEEN FIFTY-SIX<br />

College graduation is<br />

simultaneously the most joyous<br />

and nerve-wracking experience for<br />

college students. Joyous because after<br />

all the hard work and late nights, your<br />

academic achievements have finally<br />

led to this moment. Nerve-wracking<br />

because now you are faced with<br />

the reality of going out to embark<br />

on your career, utilizing all you’ve<br />

learned and putting it into action.<br />

Along with celebrating the<br />

graduates and their accomplishments,<br />

others such as family and friends feel<br />

they are a part of their success. Even<br />

more significance is attached when<br />

an embedded history of exclusion<br />

is now being changed through<br />

each graduate.<br />

Trailblazers such as 2007 graduate<br />

Sonequa Martin-Green, a native of<br />

Russellville, Alabama, have left a<br />

mark at The University of Alabama.<br />

Martin-Green received her degree<br />

in theater. She starred in a UA<br />

production of “Romeo and Juliet”<br />

as a gender-swapped Mercutio<br />

and was a part of the Alabama<br />

Forensics Council.<br />

Martin-Green has since collected<br />

acting credits in film and television.<br />

She had recurring roles on the second<br />

season of “Once Upon a Time” and<br />

as Sasha on the third season of “The<br />

Walking Dead.”<br />

These roles were a stepping stone<br />

to her biggest role to date as the<br />

lead actor in “Star Trek: Discovery”<br />

as First Officer Michael Burnham.<br />

Martin-Green made history as the<br />

first Black woman to lead the “Star<br />

Trek” series. Martin-Green was<br />

awarded for her performance with a<br />

Saturn Award in 2018.<br />

All of Martin-Green’s experiences<br />

at the University helped sharpen<br />

her skills. She credits her professors<br />

with supporting her and believing<br />

in her goals. In fact, she said her<br />

professors’ belief in her changed her<br />

in a prominent way.<br />

“I will always have a connection<br />

to UA. It’s where I come from; it’s<br />

where the seeds were sown,” Martin-<br />

Green said. “I brag about it all the<br />

time. I love it when people ask me<br />

where I’m from, and I love it when<br />

they ask if I went to school, and I<br />

go, ‘Oh yeah, yeah, I went to The<br />

University of Alabama, and I got<br />

my theater degree, and it was just an<br />

excellent education.’”<br />

The same can be said about<br />

Elliot Spillers. Spillers was a<br />

2016 graduate of The University<br />

of Alabama with a bachelor’s<br />

degree in commerce and business<br />

management. He was involved<br />

in various campus organizations<br />

such as First Year Experience, the<br />

Center for Sustainable Service<br />

and Volunteerism, the A-Book<br />

editorial board, and the Sustained<br />

Dialogue program.<br />

Along with this, Spillers was also a<br />

senate assistant and the assistant vice<br />

president of student affairs with the<br />

Student Government Association.<br />

Each of these previous positions<br />

prepared Spillers to become<br />

SGA President.<br />

Spillers’ presidency went beyond<br />

just his role on campus. Spillers was<br />

the second person of color to hold<br />

this position. Cleo Wade was the first<br />

and held the position in 1976. Over<br />

three decades had passed since a<br />

person of color was elected as SGA<br />

president. Spillers’ win was an<br />

example of how inclusive the<br />

University was becoming.<br />

Spillers’ campus work<br />

continued with advocacy<br />

for sexual assault survivors.<br />

He worked alongside<br />

the Women and Gender<br />

Resource Center. Spillers<br />

also campaigned for<br />

the creation of a<br />

Vice President of<br />

Diversity, Equity<br />

and Inclusion<br />

within SGA.<br />

Expanding<br />

upon a<br />

background of volunteer work and<br />

activism, Spillers is currently the<br />

project manager for the Equal Justice<br />

Initiative based in Montgomery,<br />

Alabama. He has worked on projects<br />

with the <strong>Legacy</strong> Museum: From<br />

Enslavement to Mass Incarceration.<br />

The museum informs individuals<br />

about the racial history of injustice.<br />

From formative beginnings, both<br />

Martin-Green and Spillers had the<br />

University as their stepping stone to<br />

showcase their talents and passions.<br />

Each step has left an<br />

impression behind<br />

for other students<br />

as guidance and<br />

encouragement<br />

that their goals<br />

are also possible<br />

to achieve.<br />

Pictured: Elliot Spillers CW File

LEGACY<br />

<strong>October</strong> 21, <strong>2021</strong><br />

CROWNED<br />

5A<br />

FARRAH SANDERS<br />

NINETEEN FIFTY-SIX<br />

As homecoming takes place at the<br />

University, we are swept with the air<br />

of tradition. Long-standing activities,<br />

competitions, parades and more await<br />

the student body every year in <strong>October</strong>.<br />

While students look forward to a good<br />

game of football, they also prepare for<br />

a much more charming and, at times,<br />

political tradition. That is the selection<br />

of the homecoming queen.<br />

Competitions of this nature have<br />

long had the stereotype of “all beauty,<br />

no brains,” but this is not the case at the<br />

University. Each hopeful homecoming<br />

queen must have a social platform, a<br />

strong educational standing backed<br />

by a favorable GPA, and time to<br />

serve her campus. The queen is<br />

expected to represent The University<br />

of Alabama and its student body as<br />

campus celebrates another year of<br />

excellence. Yet there is a long history<br />

of underrepresentation within the<br />

competition itself.<br />

“<br />

“<br />

I also got a phone call<br />

saying I was ‘too dark’ to<br />

run.<br />

JUDY<br />

BURROUGHS<br />

Black students have steadily taken<br />

part in the homecoming queen<br />

elections since Dianne Kirksey became<br />

the first Black member of the court in<br />

1970. Terry Points-Boney became the<br />

first Black homecoming queen in 1973,<br />

with Christa Valencia Hardy being the<br />

most recent Black queen in 1993. In this<br />

28-year gap, a Black student has been<br />

on the court every year representing<br />

causes and spaces that are close to their<br />

hearts. This includes Jordan Watkins,<br />

who ran in 2018.<br />

“I wanted to showcase the<br />

importance of mentorship, unity and<br />

inclusivity by contributing to diverse<br />

avenues of representation at The<br />

University of Alabama. Running for<br />

homecoming presented me<br />

with the phenomenal<br />

opportunity,”<br />

Wa t k i n s<br />

said.<br />

Watkins,<br />

a two-time<br />

graduate of<br />

the University<br />

and current doctoral<br />

candidate, centered her platform<br />

around Upward Bound, a communitybased<br />

organization that focuses on<br />

creating resources and providing<br />

support in science, mathematics,<br />

foreign language, college entrance<br />

and more. She has hope for better<br />

representation soon.<br />

“I was not only advocating for<br />

mentorship and the impact I have<br />

personally experienced but the<br />

tremendous impact it had left on<br />

countless amounts of<br />

students at UA, and<br />

because of this, yes,<br />

I felt as<br />

though I<br />

played a hand<br />

in representing<br />

a cause bigger<br />

than myself and the<br />

Black community on The<br />

University of Alabama’s campus,”<br />

Watkins said.<br />

One might ask: How has campus<br />

gone 28 years without a Black<br />

homecoming queen? It certainly isn’t<br />

due to a lack of effort.<br />

Judy Burroughs was a member of the<br />

2016 homecoming court.<br />

“To be honest, I had no intention<br />

Pictured: Christa Hardy CW Archives<br />

of running until my friend suggested I<br />

do it,” Burroughs said. “I was definitely<br />

nervous because I didn’t think I made<br />

that big of an impact on campus, but I<br />

had a lot of support along the way.”<br />

“<br />

I wanted to showcase<br />

the importance of<br />

mentorship, unity and<br />

inclusivity by contributing<br />

to diverse avenues of<br />

representation at The<br />

University of Alabama.<br />

JORDAN<br />

WATKINS<br />

“<br />

Burroughs was no stranger to<br />

conflict as an established student<br />

leader on campus. She recalled a tense<br />

incident during her campaign run.<br />

“One instance in particular was<br />

someone getting on my car while they<br />

didn’t notice that I was still in it. They<br />

were trying to erase my ‘Vote for Judy’<br />

sign on my car. I called UAPD, but<br />

that didn’t do much. I also got a phone<br />

call saying I was ‘too dark’ to run,”<br />

Burroughs said.<br />

She didn’t expect the campus to<br />

notice that she was running, but she<br />

talked to campus resources and decided<br />

to keep moving forward.<br />

This year’s homecoming festivities<br />

will be no stranger to representation.<br />

Savanah Lemon and Noelle Fall both<br />

made strong bids for homecoming<br />

queen, both being heavily involved<br />

and representing historically<br />

Black sororities.<br />

Regardless of what the future holds<br />

for Black homecoming queens at the<br />

University, we cannot forget those<br />

who came before. Terry Points-Boney,<br />

Joan Belinda Turner Woodard, Deidra<br />

Chastang, Opal Atonita Bush Butler,<br />

Kim Ashley and Christa Valencia<br />

Hardy created a legacy that will be<br />

remembered. They broke away from<br />

a perceived standard and held their<br />

crowns high.<br />

SPRING Registration<br />

BEGINS NOV. 5<br />

Learn more at sheltonstate.edu/register<br />

It is the policy of the Alabama Community College System Board of Trustees and Shelton State Community College, a postsecondary institution under its control, that no person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin, religion,<br />

marital status, disability, gender, age, or any other protected class as defined by federal and state law, be excluded from participation, denied benefits, or subjected to discrimination under any program, activity, or employment.

6A<br />

JACK MAURER<br />

THE CRIMSON WHITE<br />

It’s hard not to notice that The University<br />

of Alabama is growing. Just look at the<br />

endless parade of construction projects<br />

taking place on campus. Or ask one of the<br />

hundreds of students who were supposed<br />

to live on campus this fall, until a largerthan-expected<br />

incoming class of 7,593<br />

freshmen forced them and the University<br />

to make other arrangements.<br />

That record-breaking first-year class<br />

brought total enrollment to more than<br />

38,000 for the fourth time in the University’s<br />

history. The vast majority of UA students<br />

— some 30,700 — are undergraduates<br />

working toward a four-year degree.<br />

In the past 20 years, the number of<br />

degree-seeking undergraduates at the<br />

University has more than doubled. Yet the<br />

number of Black students in this group has<br />

risen by only 47%.<br />

Black students have been<br />

underrepresented at the University since<br />

its founding in 1831. For more than twothirds<br />

of its history, the University did not<br />

admit Black students. It was integrated<br />

less than 60 years ago, in 1963, when Gov.<br />

George Wallace stood at the door of Foster<br />

Auditorium in an unsuccessful last-ditch<br />

effort to block the entry of the University’s<br />

first two Black undergraduates.<br />

The proportion of Black degree-seeking<br />

undergraduates on campus peaked in<br />

2001, at 14.8%. Since then, it has fallen<br />

to 10.5%. Throughout the past 20 years,<br />

African Americans have accounted<br />

CW / Jack Maurer<br />

LEGACY<br />

<strong>October</strong> 21, <strong>2021</strong><br />

As UA grows, Black enrollment lags<br />

for a little more than a quarter of the<br />

state’s population.<br />

G. Christine Taylor, the University’s<br />

vice president and associate provost for<br />

diversity, equity and inclusion, declined<br />

to speculate on the reasons for this trend.<br />

During her four years at the University,<br />

the percentage of Black degree-seeking<br />

undergraduates has risen by about half a<br />

percentage point.<br />

“I just came and said, ‘Wow, we need to<br />

do better,’” Taylor said.<br />

In 2017, the University hired Taylor<br />

to lead its newly established Division of<br />

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, which<br />

was created in part to “recruit, retain and<br />

graduate more diverse students,” according<br />

to the division’s website. The following<br />

year, the share of Black degree-seeking<br />

undergraduates at the University hit a 28-<br />

year low. It has increased modestly each<br />

year since then.<br />

Gabby Kirk, a freshman majoring<br />

in secondary education, said she wasn’t<br />

surprised to hear that the share of Black<br />

students at the University had gone<br />

down in recent decades. She said she<br />

has seen Black students gravitate to<br />

historically Black colleges and universities<br />

as stigmas surrounding these institutions<br />

have eroded.<br />

“We were told that HBCUs weren’t<br />

as professional and they won’t be seen<br />

as serious in the professional world or<br />

whatever. So a lot of people went to PWIs<br />

[predominantly white institutions], but<br />

now I think ... people realize, ‘Hey, Howard<br />

can have the same credentials as Yale,’”<br />

Kirk said.<br />

She said Black students can sometimes<br />

feel unsafe at schools like The University<br />

of Alabama because of their fraught racial<br />

history and relative absence of Black<br />

faculty members and administrators. As<br />

of last year, 7.6% of faculty members at the<br />

University were Black.<br />

“Sometimes the student body has a<br />

racist history of behaving this way toward<br />

Black students,” Kirk said. “Why would I<br />

put myself in this position?”<br />

Matthew McLendon, who has served<br />

as the University’s associate vice president<br />

and executive director of enrollment<br />

management since <strong>October</strong> 2019, said the<br />

question of lagging Black enrollment is a<br />

complicated one.<br />

“I think that that’s one of those questions<br />

that researchers themselves are looking at,<br />

because I think there’s national trends that<br />

play into that,” McLendon said.<br />

A 2020 report from the Education<br />

Trust, a nonprofit focused on improving<br />

equity in education, found that between<br />

2000 and 2017, the share of Black students<br />

declined at 58% of selective public<br />

colleges, including The University of<br />

Alabama. According to the report, Black<br />

students remain underrepresented at<br />

more than 90% of selective public colleges<br />

compared to the states where these colleges<br />

are located.<br />

To alleviate such disparities, the report’s<br />

authors recommend that institutions<br />

take a number of steps, including<br />

changing recruitment strategies, offering<br />

more financial aid to students from<br />

underrepresented minorities, improving<br />

campus racial climates, and deemphasizing<br />

or ignoring standardized test scores in<br />

admission decisions.<br />

On the recruitment front, McLendon<br />

said his office has collaborated with the<br />

Division of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion<br />

to organize events such as the Multicultural<br />

Visitation Program, which took place<br />

Oct. 10, and Our Bama, an annual event<br />

for admitted minority students and their<br />

parents. He said the University plans to<br />

hire an assistant director for multicultural<br />

recruitment this year.<br />

McLendon said financial aid also<br />

plays a role in the University’s strategy<br />

for diversity, equity and inclusion. He<br />

pointed to the University’s participation in<br />

the College Board National Recognition<br />

Programs, which provide academic honors<br />

to underrepresented students based on<br />

their scores on the PSAT or Advanced<br />

Placement exams.<br />

Students who receive these honors<br />

qualify for a scholarship package from<br />

the University that includes four years of<br />

tuition, one year of on-campus housing<br />

and $4,000 in supplemental scholarships.<br />

As for standardized testing, the<br />

University stopped requiring SAT and<br />

ACT scores for undergraduate admission<br />

last year in response to the COVID-19<br />

pandemic, which made it difficult for<br />

many students to take either test.<br />

“<br />

Sometimes the student<br />

body has a racist history<br />

of behaving this way<br />

toward Black students.<br />

Why would I put myself in<br />

this position?<br />

GABBY KIRK<br />

“<br />

The Education Trust report advocates<br />

“a holistic admissions process that<br />

incorporates race as a significant factor<br />

in [admission] decisions.” The University<br />

currently does not consider race or<br />

ethnicity in its admission decisions.<br />

Taylor said the University’s diversity<br />

initiatives are driven by the idea that<br />

everyone benefits from a diverse<br />

student body.<br />

“[Diversity] makes for a better<br />

educational experience,” Taylor said. “You<br />

tend to be more civic-minded. You tend to<br />

be more critical thinkers. You tend to be<br />

more engaged in your communities.”<br />

According to a 2017 working paper<br />

from the Harvard-based research group<br />

Opportunity Insights, a UA student whose<br />

parents are in the bottom fifth of incomes<br />

has a 25% chance of entering the top fifth<br />

as an adult. That puts The University<br />

of Alabama at 600th out of 2,137<br />

U.S. colleges.<br />

Taylor said that, in general, the minority<br />

students the University hopes to attract<br />

don’t suffer from a lack of options.<br />

“Diverse students are going to college.<br />

They just may not be choosing to come<br />

to Alabama. ... It is not as if, if they’re not<br />

coming to Alabama, they’re on the side of<br />

the road,” she said. “Their choices are not<br />

us or a two-year [community college];<br />

their choices are us or Georgia Tech, us or<br />

UGA, us or Vanderbilt.”

LEGACY<br />

<strong>October</strong> 21, <strong>2021</strong><br />

Getting to know the namesake of<br />

WADE HALL<br />

1B<br />

Archie Wade standing in front of Wade Hall, a campus building recently renamed after him. CW / David Gray<br />

GRACE SCHEPIS<br />

THE CRIMSON WHITE<br />

In 1964, a young Archie Wade left<br />

an Alabama football game at halftime<br />

because of targeted racial harassment in<br />

the student section.<br />

In 1970, he was asked to help recruit<br />

Black athletes to play for the Alabama<br />

football team, where they would spend<br />

their Saturdays in the same stadium<br />

that left Wade feeling unwelcome six<br />

years prior.<br />

Last month, Wade, age 82, was<br />

recognized as the new namesake of the<br />

former Moore Hall by the UA Board of<br />

Trustees.<br />

President pro tempore of the Board<br />

of Trustees W. Stancil Starnes formed a<br />

working group last summer to conduct<br />

a “comprehensive review of all named<br />

buildings, structures, and spaces on our<br />

campuses relative to the University of<br />

Alabama System’s shared values: integrity,<br />

leadership, accountability, diversity,<br />

inclusion, and respect.”<br />

When the working group determined<br />

that Albert Burton Moore’s legacy was<br />

“inconsistent” with the current views of<br />

the University, it was time for the building<br />

on the corner of University Boulevard and<br />

Sixth Avenue to receive a new name.<br />

Trustee Emeritus John England Jr.,<br />

chair of the building names working<br />

group, led the search.<br />

“As we began our review of buildings<br />

and spaces on the System campuses, we<br />

started considering alternatives in the<br />

event we decided to recommend to the<br />

full Board of Trustees that a name be<br />

removed,” England said. “We also began<br />

receiving information from faculty<br />

and students suggesting names, which<br />

included Dr. Wade.”<br />

“<br />

We had to leave at<br />

halftime because people<br />

were throwing things and<br />

ice and cups and all that.<br />

I just thought it was best<br />

for us to leave. That was<br />

kind of a low point.<br />

ARCHIE WADE<br />

“<br />

Friends, colleagues and students<br />

advocated for Wade from the start<br />

of the process and created a petition<br />

shared across social media to encourage<br />

his selection.<br />

When the news got to Wade that he<br />

had been chosen, he was “elated.”<br />

“I had a visitation from the chairman<br />

of the committee, and one other member<br />

of the committee, earlier in the summer,”<br />

Wade said. “They just had mentioned<br />

that there was a possibility and they had<br />

submitted my name to the board, but<br />

I hadn’t heard anything else until that<br />

actually happened a couple weeks ago. I<br />

was happy.”<br />

On Sept. 17, the Board officially passed<br />

the resolution. Wade’s name is now be<br />

engraved into the campus he owes his best<br />

and worst days to.<br />

“It is my hope that students, faculty,<br />

staff, parents and visitors will want<br />

to inquire about Dr. Wade and learn<br />

about him and his contributions to The<br />

University of Alabama and the state of<br />

Alabama,” England said. “His is truly a<br />

Jackie Robinson story in the history of<br />

The University of Alabama.”<br />

Wade’s story may resemble Robinson’s<br />

in more ways than one. Sparking his<br />

interest in kinesiology and physical<br />

education was his own experience as<br />

a college baseball player. At Stillman<br />

College, a historically Black liberal arts<br />

college, Wade played four years, having<br />

never once participated in high school.<br />

“That was a blessing in itself,”<br />

Wade said.<br />

After graduating from Stillman, Wade<br />

was offered a professional contract,<br />

and played three years for the St. Louis<br />

Cardinals’ minor-league affiliate team.<br />

Following his time in the pros, Wade<br />

returned to what he felt was his true<br />

calling: education. After receiving his<br />

master’s degree at the University of West<br />

Virginia, he returned to Tuscaloosa and<br />

began both his doctorate studies and his<br />

teaching career.<br />

As professor of what was then<br />

the Health, Physical Education and<br />

Recreation Department, now known as<br />

the Department of Kinesiology, Wade<br />

cherished his time with students and<br />

enjoys staying in contact with them now.<br />

“I’ve always enjoyed the students there<br />

my whole 30 years,” Wade said. “The most<br />

enjoyable time I have now is hearing from<br />

some of those students who were in classes<br />

in 1974 and 1975. Just to hear from them.<br />

I mean I had someone visit me about two<br />

months ago that was in a class in 1974.”<br />

Wade also found his place among<br />

colleagues at a school that did not always<br />

accept him as a young Black man.<br />

“I worked with some wonderful people<br />

in our department and in the college,”<br />

Wade said. “I enjoyed all the people that<br />

treated me as well as I ever thought they<br />

would have. They accepted me. I thought<br />

at first I was being tolerated. But after five<br />

or six years, I felt like they at least accepted<br />

me for what I was and what I was trying<br />

to do and realized some things that I was<br />

going through.”<br />

Wade noticed when he was treated<br />

differently than others on campus. The<br />

University saw its first Black graduates in<br />

the ’60s, but racist attitudes were difficult<br />

to eliminate.<br />

“When I was walking down University<br />

Boulevard, there were some people that<br />

would change sides of the street just to<br />

avoid me,” Wade said. “I could tell that.<br />

But that’s okay. I just said, ‘They have a<br />

problem; I don’t.’ Because I always treat<br />

them the best I could, no matter who<br />

it was.”<br />

Wade said he believes in moving on<br />

from those experiences.<br />

“I guess in any career you’re going to<br />

have ups and downs and highs and lows<br />

and peaks and valleys and all that, but I<br />

just try to remember those things that<br />

were high, and let those things that were<br />

low kind of go away.”<br />

Among the lows was Wade’s first trip<br />

to an Alabama football game: one that<br />

was cut short due to harassment from<br />

other students among the crowd. At the<br />

time, Wade was a Tuscaloosa resident<br />

attending Stillman.<br />

“I was one of the three people who<br />

tried to go to the game at Denny Stadium,”<br />

Wade said. “The President gave us three<br />

tickets. I was one of those three that went<br />

out there, along with Dr. Joffre Whisenton<br />

and Nathaniel Howard. We were the three<br />

from Tuscaloosa who went to, in a way,<br />

integrate the stands. We had to leave at<br />

halftime because people were throwing<br />

things and ice and cups and all that. I just<br />

thought it was best for us to leave. That<br />

was kind of a low point.”<br />

“[The stadium has] been renovated,<br />

refurbished, and all that, but that’s that<br />

place where I was, where they didn’t want<br />

me to do it in 1964,” Wade said.“The year’s<br />

<strong>2021</strong>, and you see all the players, and you<br />

see their progress. I’m just amazed at it.<br />

And I know we still have a lot more to do<br />

and a lot more things to take care of, but at<br />

least I think we’re making strides towards<br />

our goal where everybody is treated fairly<br />

and equally.”<br />

Wade applauded the University’s efforts<br />

but said there is always room for more.<br />

“I grew up in a segregated [society]. I<br />

know nothing about going to school with<br />

a different race. That didn’t happen to me<br />

until I went to college,” Wade said.<br />

Growing up, Wade was used to playing<br />

with children of other races. He spent<br />

time with his best friend, then had to<br />

watch him go to a school Wade was not<br />

allowed to attend. Instead, he caught a<br />

bus, and was taken seven miles away to<br />

the Black school across town.<br />

While these experiences stick with<br />

Wade, he feels no need to publish them<br />

for others.<br />

“Some people have asked me why I<br />

haven’t written anything down, a book<br />

about things, about what happened and<br />

stuff, and I told them I didn’t really want to<br />

do that,” Wade said. “I’ve talked to people<br />

about it, but there were some bad times<br />

for me. But there were so few, I don’t even<br />

mention them. That’s the way I feel about<br />

it. I look at things and think if they’re<br />

important or not important. Even though<br />

it was important to me, I don’t think it’s<br />

important in the whole scheme of things,<br />

so I don’t mention it.”<br />

According to Wade, this aspect of his<br />

character can be credited to his parents,<br />

who are no longer around but continue to<br />

inspire him.<br />

“I always say I had wonderful parents,”<br />

Wade said. “They supported me; they did<br />

everything else I could ask a parent to<br />

do for their kid. They always told me to<br />

treat people right and do fair and work<br />

hard and stay focused, and it helped.<br />

They’re the ones that told me if things are<br />

important, take care of it; if things are not<br />

important, let it go. I think about it almost<br />

every day.”<br />

Wade is now surrounded by his wife<br />

of 60 years, his five children and nine<br />

grandchildren.<br />

Wade smiled as he reflected on his<br />

years at the University, on the field<br />

and since.<br />

“I’ve had a good life. I’ve enjoyed it,”<br />

Wade said. “I had a chance to meet a lot of<br />

great people. People I read about.”<br />

According to the UA Board of Trustees,<br />

the work of the building names working<br />

group is still ongoing in evaluating<br />

current namesakes.<br />

Shop Boots,<br />

Jeans, & Hats<br />

at The Wharf<br />

in Northport<br />

220 Mcfarland Blvd N (205)-752-2075

2B<br />

MORE THAN A CROWN<br />

CLAIRE YATES & RACHEL PARKER<br />

THE CRIMSON WHITE & NINETEEN FIFTY-SIX<br />

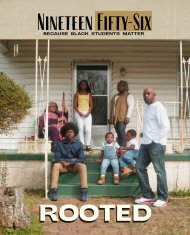

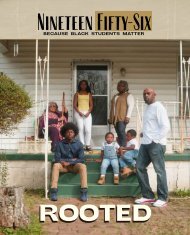

Farrah Sanders wins Miss Black and Old<br />

Gold. Courtesy of Farrah Sanders<br />

Pageants and homecoming courts<br />

may seem cliché, but there is a message<br />

behind the pursuit for royalty. Former<br />

UA students Tiara Pennington and<br />

E’talia Shakir, along with current student<br />

Farrah Sanders, broke stereotypes when<br />

they pursued the crown.<br />

All three women showcased Black<br />

royalty in unique ways by advocating<br />

for a cause, displaying sisterhood and<br />

sharing an impactful message.<br />

Pennington held the title of Miss<br />

Alabama 2019 and 2020. She said that<br />

her initial interest in pageants was<br />

the possibility of winning scholarship<br />

money. The financial incentive eased<br />

college expenses while also giving<br />

Pennington a chance to showcase her<br />

opera talents.<br />

The year that Pennington won<br />

the title, she also won the overall<br />

talent award, which is her favorite<br />

phase of competition. Not only did<br />

she enjoy competing, but she also<br />

loved the true friendships and bonds<br />

that she made throughout the Miss<br />

America Organization.<br />

“We do our makeup with each other,<br />

we don’t try to sabotage each other,<br />

we really understand that all of us<br />

have worked so hard to get here at this<br />

moment, and so we all should just be<br />

uplifting each other,” Pennington said.<br />

Pennington made history when she<br />

became the first Black woman to win<br />

Miss University of Alabama in 2019.<br />

Pennington wanted to inspire others<br />

who were timid about being involved<br />

with pageantry. The Miss America<br />

Organization provides a crown to the<br />

winner, and the crown can give women<br />

a voice.<br />

Pennington promoted her platform,<br />

Psoriasis Take Action Alabama. She also<br />

advocated for diversity within the Miss<br />

America Organization itself.<br />

“We are more than just beauty queens.<br />

We’re more than just pageant girls,”<br />

Pennington said. “This organization is<br />

filled with some of the most intelligent<br />

young women you will ever meet in your<br />

whole entire life.”<br />

Pennington’s thoughts are echoed by<br />

the current Miss Black and Old Gold,<br />

Farrah Sanders. Sanders won the title<br />

in 2019 and viewed her crowning as an<br />

opportunity bigger than herself.<br />

“Miss Black and Old Gold means<br />

another avenue of advocacy for me, and to<br />

me it offers a space to be able to represent<br />

my student body, my community of<br />

Tuscaloosa, my community of UA, my<br />

state of Alabama,” Sanders said.<br />

Sanders’ involvement in the Miss<br />

Black and Old Gold pageant began<br />

between conversations with friends in<br />

Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. who<br />

suggested she compete. She was initially<br />

apprehensive due to personal health<br />

struggles, but still decided to compete.<br />

“That was the first time that I felt<br />

somewhat like myself, and so I looked<br />

at that, and I said ‘Wow. I know I’m not<br />

the only Black woman that feels like that.’<br />

I know I’m not. This isn’t some singular<br />

experience,” Sanders said.<br />

Sanders expanded on her platform of<br />

mental health following her win through<br />

her organization, My Mind Matters.<br />

Focusing on the mental health of women<br />

of color along with societal expectations,<br />

this platform spoke to these challenges<br />

and the importance of mental and<br />

physical health.<br />

Sanders’ personal connection was<br />

strengthened when she considered how<br />

her position as Miss Black and Old Gold<br />

is viewed through the eyes of others,<br />

particularly young girls of color.<br />

“Having them see a physical<br />

embodiment of someone that they<br />

haven’t seen before, and being able<br />

to come up to little girls and be that<br />

inspiration,” Sanders said. “Having<br />

them say ‘I want that. I want that crown<br />

like yours.’ ... And it means being able<br />

to inspire, being able to advocate and<br />

being able to be present for the body<br />

and community of people that I love and<br />

respect so much.”<br />

From the impact on young girls to<br />

the campus community, Sanders’ victory<br />

felt inclusive of everyone. Sanders was<br />

reminded that her title went beyond her<br />

initial pageant win. She felt the pride<br />

and support from the Black community<br />

of the University as a representative<br />

of them and other students across<br />

the nation.<br />

“That in this moment, it was like we<br />

all felt seen, and I think they trusted me<br />

enough to know that I will continue to<br />

help you feel seen even with this crown,”<br />

Sanders said.<br />

E’talia Shakir was on The University<br />

of Alabama’s homecoming court in<br />

2019. Shakir was the only minority<br />

candidate and wanted to be a strong<br />

representative for other minorities. She<br />

represented her sorority, Delta Sigma<br />

Theta, and other historically Black<br />

Greek-letter organizations.<br />

Shakir was pleased with the amount of<br />

love and support she got from Alabama’s<br />

Panhellenic Association. They were able<br />

to support and help her impact others,<br />

regardless of the organization she was a<br />

LEGACY<br />

<strong>October</strong> 21, <strong>2021</strong><br />

part of. Being a minority, she appreciated<br />

the support she got and she wanted to<br />

give back to others who looked like her.<br />

“I was the only minority on<br />

homecoming court in 2019, and so<br />

I thought of it more [as] I was there<br />

representing people or women that<br />

look like me, and that was a huge thing,”<br />

Shakir said. “I was also in Capstone Men<br />

and Women, so getting questions in<br />

terms of recruiting at Alabama and what<br />

it is like being a minority at Alabama<br />

meant a little bit more when I thought of<br />

it in that way.”<br />

Along with the image she is projecting<br />

to others for encouragement, Shakir<br />

was also receiving her own through<br />

her network of self-described, “Bama<br />

Mamas.” This was a group of women,<br />

composed of her advisor and Kim<br />

Pettway, who offered support in the<br />

midst of stress.<br />

“You’re always leaving the door open<br />

for the people behind you,” Shakir said.<br />

“As you’re accomplishing, knocking<br />

down these new doors, these new<br />

barriers, always make sure you have that<br />

one hand extended behind to kind of<br />

pull the people up with you.”<br />

Through support, sisterhood and<br />

the ability to advocate for a cause, these<br />

women have shown that it is much more<br />

than just a sparkly crown at stake.<br />

Farrah Sanders is the culture<br />

and lifestyle director at Nineteen<br />

Fifty-Six Magazine.<br />

This is our water.<br />

Help UA protect it.<br />

Only rain down the drain.<br />

For questions, comments, or concerns about Storm<br />

Water, contact Environmental Health & Safety<br />

Phone: (205) 348-5905<br />

Website: ehu.ua.edu<br />

Twitter: EHS_UA<br />

2610 McFarland Blvd East<br />

McFarland Plaza<br />

Old Steinmart Location<br />

Your Party, Our Pleasure

LEGACY<br />

<strong>October</strong> 21, <strong>2021</strong><br />

THE TRUE ORIGINS OF ROCK ‘N’ ROLL<br />

3B<br />

SYM POSEY & MADDY REDA<br />

THE CRIMSON WHITE<br />

When most people hear rock ’n’ roll,<br />

they think of Elvis Presley, clad in his<br />

star-spangled jumpsuit, but they typically<br />

don’t think of the generations of Black<br />

musicians, like Little Richard or Fats<br />

Domino, who laid the foundations of<br />

rock music.<br />

Alexis Davis-Hazell, an assistant<br />

professor of voice and lyric diction said<br />

it is impossible to talk about American<br />

music without talking about the African<br />

American tradition that goes into it.<br />

“They are woven. You cannot talk about<br />

one without the other. It is a foundational<br />

element and it is part of what makes<br />

American music unique from other<br />

national music,” Davis-Hazell said.<br />

The culture of mainstream American<br />

music is closely intertwined with racism<br />

and segregation.<br />

According to the Oakland Public<br />

Library, Black music genres can be traced<br />

back to the days of slavery, when enslaved<br />

people would sing to each other to pass<br />

along messages and share their life stories.<br />

As Christianity gradually made its<br />

way into the culture of slaves in the<br />

United States, the hymns they sang would<br />

eventually be termed spirituals, which<br />

would later evolve into gospel music.<br />

This became the foundation of the blues,<br />

a genre of music that expressed the Black<br />

community’s disappointment in the lack<br />

of freedoms and rights that came in a postslavery,<br />

Jim Crow society.<br />

Eric Weisbard, a professor of American<br />

studies, said the international craze for<br />

American music — most notably, rock<br />

’n’ roll — began with minstrel shows, the<br />

theatrical act of white actors performing<br />

in blackface.<br />

“The phrase ‘Jim Crow’ came from the<br />

beginning of blackface minstrelsy in the<br />

1830s. An artist named Thomas Rice, a<br />

white artist, put tar on his face, pretended<br />

to be a Black person, and gave a songand-dance<br />

routine called Jim Crow,”<br />

Weisbard said.<br />

Weisbard said minstrel shows proved to<br />

be so internationally popular that Rice was<br />

taken to England to perform for royalty.<br />

“Every part of the United States had<br />

its own acts of people doing this kind of<br />

work. Jim Crow names segregation and<br />

names the beginning of commercial<br />

American music as this international<br />

craze,” Weisbard said. “So it’s there. 200<br />

years ago, it’s there practically from<br />

the beginning.”<br />

Davis-Hazell said that the genesis of<br />

rock ’n’ roll is not the first time aspects<br />

of Black culture have been co-opted by<br />

dominant white culture.<br />

“It is a pattern that goes all the way back<br />

to the very first popular music of America<br />

that was a truly American form, which was<br />

blackface minstrelsy,” Davis-Hazell said.<br />

“That lays the foundation for the comfort<br />

and the commoditization of Black culture,<br />

whether it’s authentic or not.”<br />

The overwhelming commercial success,<br />

prestige and recognition white rock ’n’<br />

roll singers received compared to Black<br />

pioneers of the same genre are staggering.<br />

There are many examples of white<br />

artists re-recording Black-owned songs,<br />

such as The Beatles covering “Please Mister<br />

Postman” by the Marvelettes, or Elvis<br />

Presley covering “Hound Dog,” which was<br />

originally written for Big Mama Thornton.<br />

These songs were copied and rearranged<br />

to be more digestible for a white audience.<br />

Davis-Hazell said early rock ’n’ roll’s<br />

popularity with white teenagers allowed<br />

the nomenclature to catch on, going<br />

beyond white artists doing covers and<br />

gradually turning into white artists actually<br />

attempting to emulate the style.<br />

“It’s absolutely the case that the history<br />

of American popular music turns on racial<br />

appropriation,” Weisbard said. “The idea<br />

that the same process of white people often<br />

loving Black music seems to constantly<br />

involve taking it and profiting from it in<br />

ways that many Black performers are not<br />

able to profit from.”<br />

As entertainment executives sought<br />

to make a profit, Black artists like Sister<br />

Rosetta Tharpe, commonly known as the<br />

“Godmother of Rock ’n’ Roll,” and their<br />

contributions to music were forgotten.<br />

Tharpe started playing and singing in<br />

church as a child prodigy at four years old,<br />

touring the South along with her mother’s<br />

evangelistic choir to hone her music skills.<br />

Tharpe skyrocketed during the 1930s<br />

and ’40s, attaining mass popularity with<br />

her gospel songs infused with electric<br />

guitar. These infusions laid the foundation<br />

for the sound of rock ’n’ roll today, as<br />

Tharpe is regarded to be one of the most<br />

dominant inspirations for artists like<br />

Little Richard, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins,<br />

Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley and Jerry<br />

Lee Lewis.<br />

Little Richard, a direct product of<br />

Tharpe’s musical inspiration, was one of<br />

the first Black rock ’n’ roll performers who<br />

catered to gay audiences both of which<br />

have become rock ’n’ roll staples.<br />

According to Florida State University,<br />

“Little Richard began garnering fans from<br />

both sides of the civil rights divide” after<br />

the release of his hit track “Tutti Frutti,”<br />

bringing Black and white fans together and<br />

challenging the harsh lines of segregation.<br />

Davis-Hazell said the record industry<br />

was terrible about awarding royalties<br />

to Black singers and songwriters, citing<br />

Little Richard as one of the first examples<br />

of Black artists having their work stolen<br />

by white artists and receiving little to<br />

no credit.<br />