Exquisite Reality: Photography and the Invention of Nationhood, 1851–1900

Review the publication that accompanies "Exquisite Reality: Photography and the Invention of Nationhood, 1851-1900."

Review the publication that accompanies "Exquisite Reality: Photography and the Invention of Nationhood, 1851-1900."

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

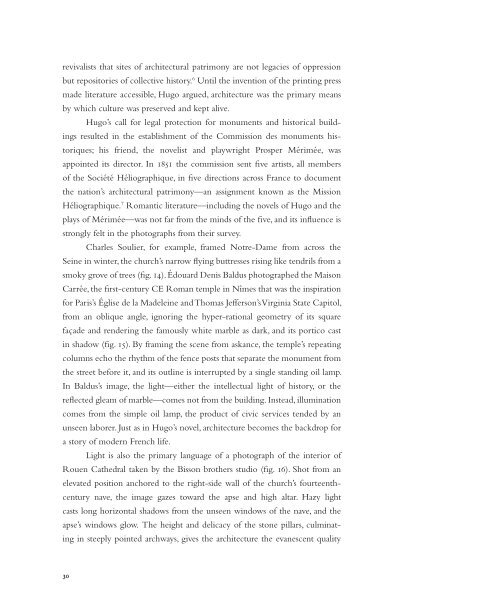

evivalists that sites <strong>of</strong> architectural patrimony are not legacies <strong>of</strong> oppression<br />

but repositories <strong>of</strong> collective history. 6 Until <strong>the</strong> invention <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> printing press<br />

made literature accessible, Hugo argued, architecture was <strong>the</strong> primary means<br />

by which culture was preserved <strong>and</strong> kept alive.<br />

Hugo’s call for legal protection for monuments <strong>and</strong> historical buildings<br />

resulted in <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Commission des monuments historiques;<br />

his friend, <strong>the</strong> novelist <strong>and</strong> playwright Prosper Mérimée, was<br />

appointed its director. In 1851 <strong>the</strong> commission sent five artists, all members<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Société Héliographique, in five directions across France to document<br />

<strong>the</strong> nation’s architectural patrimony—an assignment known as <strong>the</strong> Mission<br />

Héliographique. 7 Romantic literature—including <strong>the</strong> novels <strong>of</strong> Hugo <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

plays <strong>of</strong> Mérimée—was not far from <strong>the</strong> minds <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> five, <strong>and</strong> its influence is<br />

strongly felt in <strong>the</strong> photographs from <strong>the</strong>ir survey.<br />

Charles Soulier, for example, framed Notre-Dame from across <strong>the</strong><br />

Seine in winter, <strong>the</strong> church’s narrow flying buttresses rising like tendrils from a<br />

smoky grove <strong>of</strong> trees (fig. 14). Édouard Denis Baldus photographed <strong>the</strong> Maison<br />

Carrée, <strong>the</strong> first-century CE Roman temple in Nîmes that was <strong>the</strong> inspiration<br />

for Paris’s Église de la Madeleine <strong>and</strong> Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia State Capitol,<br />

from an oblique angle, ignoring <strong>the</strong> hyper-rational geometry <strong>of</strong> its square<br />

façade <strong>and</strong> rendering <strong>the</strong> famously white marble as dark, <strong>and</strong> its portico cast<br />

in shadow (fig. 15). By framing <strong>the</strong> scene from askance, <strong>the</strong> temple’s repeating<br />

columns echo <strong>the</strong> rhythm <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fence posts that separate <strong>the</strong> monument from<br />

<strong>the</strong> street before it, <strong>and</strong> its outline is interrupted by a single st<strong>and</strong>ing oil lamp.<br />

In Baldus’s image, <strong>the</strong> light—ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> intellectual light <strong>of</strong> history, or <strong>the</strong><br />

reflected gleam <strong>of</strong> marble—comes not from <strong>the</strong> building. Instead, illumination<br />

comes from <strong>the</strong> simple oil lamp, <strong>the</strong> product <strong>of</strong> civic services tended by an<br />

unseen laborer. Just as in Hugo’s novel, architecture becomes <strong>the</strong> backdrop for<br />

a story <strong>of</strong> modern French life.<br />

Light is also <strong>the</strong> primary language <strong>of</strong> a photograph <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> interior <strong>of</strong><br />

Rouen Ca<strong>the</strong>dral taken by <strong>the</strong> Bisson bro<strong>the</strong>rs studio (fig. 16). Shot from an<br />

elevated position anchored to <strong>the</strong> right-side wall <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> church’s fourteenthcentury<br />

nave, <strong>the</strong> image gazes toward <strong>the</strong> apse <strong>and</strong> high altar. Hazy light<br />

casts long horizontal shadows from <strong>the</strong> unseen windows <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nave, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

apse’s windows glow. The height <strong>and</strong> delicacy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stone pillars, culminating<br />

in steeply pointed archways, gives <strong>the</strong> architecture <strong>the</strong> evanescent quality<br />

30