Exquisite Reality: Photography and the Invention of Nationhood, 1851–1900

Review the publication that accompanies "Exquisite Reality: Photography and the Invention of Nationhood, 1851-1900."

Review the publication that accompanies "Exquisite Reality: Photography and the Invention of Nationhood, 1851-1900."

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

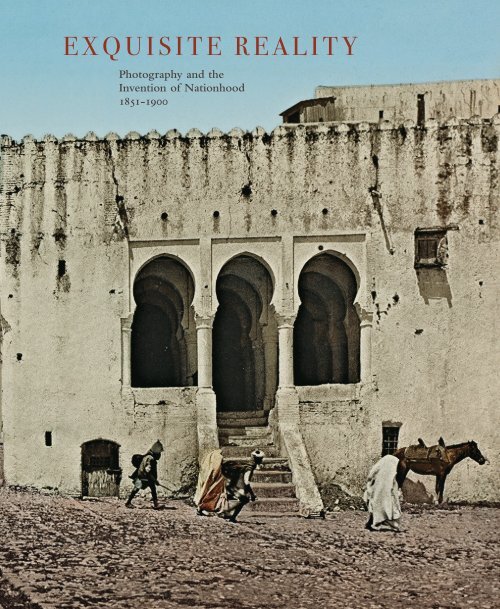

EXQUISITE REALITY<br />

<strong>Photography</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Invention</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nationhood</strong><br />

1851-1900

To view this online exhibition please visit<br />

http://cantor.2.vu/exquisite

EXQUISITE REALITY<br />

<strong>Photography</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Invention</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nationhood</strong><br />

1851-1900<br />

Danny Smith

EXQUISITE REALITY<br />

<strong>Photography</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Invention</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nationhood</strong><br />

1851-1900<br />

fig. 1<br />

Félix Bonfils (French,<br />

1831–1885), Caliph’s Tomb,<br />

19th century. Albumen<br />

print. Gift <strong>of</strong> Joseph Folberg,<br />

1994.86.10<br />

THE CITY OF THE DEAD<br />

In 1867, a young French bookbinder named Félix Bonfils opened a photography<br />

studio in Beirut. From <strong>the</strong> Lebanese capital he traveled across <strong>the</strong><br />

Middle East, making portraits <strong>and</strong> capturing architectural images <strong>and</strong> sweeping<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes. 1 On one visit to Cairo, Bonfils took a picture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mausolea <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> medieval Abbasid Caliphate in Cairo’s al-Qarafa ,(ةفارقلا) <strong>the</strong> sprawling<br />

cemetery known in English as <strong>the</strong> City <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dead (fig. 1). In <strong>the</strong> photograph,<br />

in front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> domed mausolea <strong>and</strong> minarets <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mosques, five camels<br />

st<strong>and</strong> in perfect pr<strong>of</strong>ile. A small child in dark robes holds <strong>the</strong> first camel on a<br />

lead. O<strong>the</strong>rs, similarly clad in Bedouin robes <strong>and</strong> turbans, congregate around<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r camels. Bonfils’s photograph is taken from a distance such that fully<br />

<strong>the</strong> bottom third shows Cairo’s dusty, rocky soil. The solemnity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> figures,<br />

<strong>the</strong> silence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tombs, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> almost geometric rigidity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> camels all<br />

project <strong>the</strong> formal air <strong>of</strong> a funeral. Bonfils’s own distance from <strong>the</strong> scene puts<br />

<strong>the</strong> viewer at a respectful remove. At <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> image, an inscription<br />

reads “Ensemble des tombeaux des Califes.” The figures <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir wellbehaved<br />

camels go unmentioned—<strong>the</strong>y are simply <strong>the</strong> anonymous, living parts<br />

<strong>of</strong> this funerary ensemble.<br />

5

Around <strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>the</strong> photographer Pascal Sébah framed an image<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same l<strong>and</strong>scape (fig. 2). His picture has no figures, simply <strong>the</strong> domes<br />

<strong>and</strong> minarets <strong>of</strong> al-Qarafa, stark against a white sky. In <strong>the</strong> earth in <strong>the</strong> foreground<br />

are rectilinear pylons, unmistakable signs <strong>of</strong> new construction. Unlike<br />

<strong>the</strong> French Bonfils, Sébah was an Ottoman, born in Istanbul to a Syrian fa<strong>the</strong>r<br />

<strong>and</strong> an Armenian mo<strong>the</strong>r. 2 Whereas Bonfils frequently stylized <strong>and</strong> dramatized<br />

an exotic Middle East for European audiences—in his studio, he <strong>and</strong> his wife<br />

<strong>and</strong> son dressed in robes <strong>and</strong> acted out scenes from <strong>the</strong> Bible against orientalizing<br />

backdrops—Sébah generally depicted <strong>the</strong> Middle East <strong>and</strong> its diversity<br />

as pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> breadth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ottoman Empire, which <strong>the</strong>n controlled Cairo.<br />

He captured l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> portraits, <strong>and</strong> even undertook an anthropological<br />

study <strong>of</strong> local fashion in <strong>the</strong> distant corners <strong>of</strong> Ottoman control for <strong>the</strong> painter<br />

Osman Hamdi Bey.<br />

fig. 2<br />

Pascal Sébah (Turkish,<br />

1823–1886), Tombs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Caliphs, Cairo, 19th century.<br />

Albumen print. Gift <strong>of</strong><br />

Joseph Folberg, 1994.68.115<br />

6

Bonfils framed his scene as a glimpse into a remote, oriental past despite<br />

<strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> Bedouins were likely hired for <strong>the</strong> purpose <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> tombs in<br />

<strong>the</strong> background were <strong>the</strong> burial sites not <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir elders but <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> leaders <strong>of</strong> a<br />

caliphate that hadn’t held power in Cairo since <strong>the</strong> mid-sixteenth century. He<br />

effectively rendered <strong>the</strong> buildings as part <strong>of</strong> a continuous <strong>and</strong> unchanging history<br />

in <strong>the</strong> present. Sébah’s photograph draws a hard line between <strong>the</strong> ancient<br />

tombs <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> new buildings soon to rise beside <strong>the</strong>m: a stone wall keeps<br />

history to one side <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> future in <strong>the</strong> foreground. Both Bonfils <strong>and</strong> Sébah<br />

catered in part to <strong>the</strong> tourist trade, selling <strong>the</strong>ir work to Europeans visiting <strong>the</strong><br />

Middle East <strong>and</strong> shipping prints to sell in <strong>the</strong> capitals <strong>of</strong> Europe. But European<br />

tourism funded a greater part <strong>of</strong> Bonfils’s work, <strong>and</strong> his photographs captured<br />

Cairo as Europeans imagined it. Before his lens, it was still a city in <strong>the</strong> past.<br />

Sébah, whose studio became <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficial photographer first to <strong>the</strong> Prussian<br />

state <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n to <strong>the</strong> Ottoman sultan, depicted Cairo as a modernizing city,<br />

part <strong>of</strong> an empire looking toward <strong>the</strong> future under <strong>the</strong> stabilizing force <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Ottoman government.<br />

Emerging as an art form just as <strong>the</strong> modern boundaries <strong>of</strong> Europe<br />

were being established in <strong>the</strong> nineteenth century, <strong>the</strong> medium <strong>of</strong> photography<br />

became an ideally modern means <strong>of</strong> illustrating what a nation was.<br />

Governments commissioned photographic surveys documenting <strong>the</strong> history<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir nations to build <strong>and</strong> bolster collective identity. O<strong>the</strong>r photographers<br />

ventured abroad, <strong>the</strong>ir images fueling popular support for foreign invasion<br />

<strong>and</strong> colonization in <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong> nation building. Sébah’s <strong>and</strong> Bonfils’s dueling<br />

images <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same setting reflect <strong>the</strong> ideological function <strong>of</strong> photography in<br />

nineteenth-century Europe. Both faithfully reproduce <strong>the</strong> same scene at <strong>the</strong><br />

same historical moment, but <strong>the</strong>y suggest two sharply different realities, <strong>and</strong><br />

serve two drastically divergent political goals.<br />

RIEN N’EST BEAU QUE LE VRAI<br />

In February 1851, sixteen years before Bonfils opened his studio in Beirut,<br />

France’s nascent Société Héliographique announced <strong>the</strong> birth <strong>of</strong> a new medium<br />

in <strong>the</strong> first issue <strong>of</strong> its new journal, La Lumière. They called <strong>the</strong> process heliography,<br />

a name drawn from <strong>the</strong> Greek words for sun (helios) <strong>and</strong> for drawing<br />

or writing (graphein). The medium used <strong>the</strong> careful exposure <strong>of</strong> light-sensitive<br />

material, invented in 1825 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, to create a faithful<br />

7

eproduction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world: a perfect drawing made by <strong>the</strong> sun itself. Writing in<br />

La Lumière’s introduction, <strong>the</strong> critic Francis Wey championed heliography as <strong>the</strong><br />

first modern art form: <strong>the</strong> true marriage <strong>of</strong> laboratory science <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> fine arts.<br />

The technique that Niépce had perfected in 1825 produced a single<br />

image through a lengthy <strong>and</strong> complicated process. In <strong>the</strong> decades between<br />

Niépce’s invention <strong>and</strong> La Lumière’s proclamation, <strong>the</strong> bulky camera obscura—<br />

<strong>the</strong> contraption that regulated <strong>the</strong> light reaching <strong>the</strong> prepared photosensitive<br />

material—was refined into a small wooden box fitted with glass lenses. In<br />

1839 Niépce’s partner, Louis Daguerre, adapted <strong>the</strong> camera obscura to expose<br />

small pieces <strong>of</strong> copper plated with light-sensitive silver. These images, called<br />

daguerreotypes, could be produced in as little as ten minutes, as opposed to <strong>the</strong><br />

hours-long exposure required <strong>of</strong> Niépce’s early experiments, but daguerreotypes<br />

are unique <strong>and</strong> cannot be reproduced. At almost <strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>the</strong><br />

English scientist Henry Fox Talbot applied a similar photosensitive silver iodide<br />

material to paper. When <strong>the</strong> treated paper was “drawn upon” by light in <strong>the</strong><br />

camera obscura, it created a translucent negative, an exact inversion <strong>of</strong> what it<br />

was exposed to. That paper negative could <strong>the</strong>n be used to create an infinite<br />

number <strong>of</strong> identical positive prints.<br />

Heliography was true to its name, Wey stressed—its result was a pure<br />

expression <strong>of</strong> reality, as if drawn by <strong>the</strong> sun. In La Lumière’s introduction he<br />

wrote that <strong>the</strong> medium would, <strong>the</strong>refore, be untouched by politics, that it<br />

would only ever tell <strong>the</strong> absolute, natural truth. The “steadfast motto” <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

new craft, he wrote, would be: “Nothing is beautiful but <strong>the</strong> truth.” Yet even<br />

as <strong>the</strong> Société Héliographique cheered <strong>the</strong> new process as a science, an art, an<br />

apolitical medium, Wey added a telling coda to his “steadfast motto”: “Nothing<br />

is beautiful but <strong>the</strong> truth, but it must be chosen” (Rien n’est beau que le vrai;<br />

mais il faut le choisir). 3 Heliography, or photography, as it later became better<br />

known, could reproduce <strong>the</strong> world in its exact, honest beauty, but it still<br />

needed <strong>the</strong> h<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> a discerning artist to “choose” <strong>the</strong> truth to depict: to guide<br />

<strong>the</strong> natural process <strong>of</strong> creating <strong>the</strong> honest <strong>and</strong> beautiful image.<br />

EXQUISITE REALITY<br />

In <strong>the</strong> decades that followed Wey’s pronouncement that photography would<br />

be an apolitical medium <strong>of</strong> honest beauty, quite <strong>the</strong> opposite proved true.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> late nineteenth century, as <strong>the</strong> newly formed <strong>and</strong> unified nations <strong>of</strong><br />

8

Europe <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle East sought to define <strong>the</strong>mselves <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir distinct<br />

histories, photography served a critical political role. Photographers in Italy, a<br />

state whose modern boundaries were only established in 1861, depicted <strong>the</strong><br />

monuments <strong>and</strong> legacies <strong>of</strong> disparate <strong>and</strong> once warring regions as <strong>the</strong> history<br />

<strong>of</strong> a common nation. In France, photographers were sent from Paris to rural<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nation to record <strong>the</strong> architectural history as part <strong>of</strong> a program <strong>of</strong><br />

centralizing political <strong>and</strong> cultural power in <strong>the</strong> capital. In Britain, photographers<br />

likewise took to <strong>the</strong> countryside, fueled by <strong>the</strong> popular Gothic Revival<br />

movement to document <strong>the</strong> monuments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle Ages, imagining<br />

<strong>the</strong>m as <strong>the</strong> source <strong>of</strong> modern British power <strong>and</strong> an antidote to <strong>the</strong> ills <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Industrial Revolution.<br />

At home, images <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> past stood for a collective history, <strong>the</strong> foundation<br />

<strong>of</strong> a modern state. Abroad, images <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> past represented an omnipresent<br />

<strong>and</strong> unchanging force that needed to be overcome, tamed in <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong><br />

modernization. In France in particular, a nation whose boundaries exp<strong>and</strong>ed<br />

dramatically in <strong>the</strong> nineteenth century through conquest <strong>and</strong> colonization,<br />

photographs like Bonfils’s <strong>of</strong> North Africa, <strong>the</strong> Middle East, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Holy L<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> Jerusalem fueled <strong>the</strong> popular imagination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Maghreb <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Levant<br />

as an exotic o<strong>the</strong>r trapped in <strong>the</strong> past, a l<strong>and</strong> equally alluring <strong>and</strong> repugnant, a<br />

region primed for <strong>the</strong> civilizing force <strong>of</strong> colonization.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> fifth issue <strong>of</strong> its journal, <strong>the</strong> Société Héliographique celebrated<br />

<strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong> its medium but failed to notice <strong>the</strong> full extent <strong>of</strong> its political<br />

ramifications. “Every day,” Wey wrote, “<strong>the</strong> Société Héliographique receives<br />

images representing distant <strong>and</strong> unknown sites, historical monuments, <strong>the</strong><br />

ruins <strong>of</strong> Greece, <strong>of</strong> Egypt, or <strong>of</strong> India; subjects indeed <strong>of</strong> a particular interest<br />

to a scholar, to a naturalist, to an artist, or to an antiquarian: subjects depicted<br />

for <strong>the</strong> first time in <strong>the</strong>ir exquisite reality, <strong>and</strong> that, <strong>of</strong>tentimes, defy precision<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most adroit pencil or <strong>the</strong> most minute brush. These images are, <strong>the</strong>mselves,<br />

revelations.” 4 But <strong>the</strong>se images <strong>of</strong> history <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> nationhood were not<br />

simply <strong>the</strong> purview <strong>of</strong> artists, scholars, <strong>and</strong> antiquarians; <strong>the</strong>y were tools for<br />

politicians, rulers, <strong>and</strong> kings, who saw in <strong>the</strong>ir “exquisite reality” <strong>the</strong> political<br />

ideologies <strong>the</strong>y wished to project. By depicting <strong>the</strong>se “distant <strong>and</strong> unknown<br />

sites”—monuments <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes both at home <strong>and</strong> abroad—photographers<br />

provided a visual language with which governments defined <strong>the</strong>ir nations <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir national desires.<br />

9

Pascal Sébah<br />

Pascal Sébah’s prolific photographic career blurred lines between nationalist<br />

documentation, anthropological illustration, <strong>and</strong> outright exoticizing orientalism.<br />

From his studio, known as El Chark Société Photographic (The Orient<br />

<strong>Photography</strong> Company), Sébah sold images <strong>of</strong> Istanbul primarily to French<br />

tourists. He also worked closely with <strong>the</strong> painter <strong>and</strong> curator Osman Hamdi<br />

Bey, who likewise promoted an orientalizing image <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle East popular<br />

with French audiences.<br />

The Ottoman government chafed at <strong>the</strong> simplistic <strong>and</strong> racialized image<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle East as a l<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> Bedouins, pyramids, <strong>and</strong> snake charmers that<br />

was marketed to European tourists. Eager to cast its empire as rooted in history,<br />

not trapped by it, <strong>the</strong> Ottoman state commissioned Sébah <strong>and</strong> Hamdi<br />

to write <strong>and</strong> illustrate a history <strong>of</strong> fashion <strong>and</strong> style across <strong>the</strong> empire for <strong>the</strong><br />

Ottoman pavilion at <strong>the</strong> 1873 Vienna Universal Exposition. Their volume, Les<br />

Costumes Populaires de la Turquie en 1873, shows <strong>the</strong> diverse people <strong>of</strong> Turkey<br />

<strong>and</strong> surrounding nations dressed in <strong>the</strong>ir traditional finery, <strong>and</strong> its French text<br />

<strong>and</strong> European distribution demonstrated <strong>the</strong> Ottoman interest in controlling<br />

<strong>the</strong> image <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir peoples abroad.<br />

After Sébah’s death in 1886, his son, Jean, carried on this project. He partnered<br />

with <strong>the</strong> French photographer Polycarpe Joiallier to depict <strong>the</strong> Ottoman<br />

Empire from a distinctly Ottoman perspective <strong>and</strong> eventually became Sultan<br />

Abdul Hamid II’s <strong>of</strong>ficial photographer. Their view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city <strong>of</strong> Bursa in<br />

northwestern Turkey, labeled with <strong>the</strong> city’s French name, Brousse, exemplifies<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir approach. The depicted l<strong>and</strong>scape could be any French village if not for<br />

<strong>the</strong> gleaming white mosque that anchors <strong>the</strong> center, asserting its Ottoman<br />

identity. These images have a political afterlife even today, as nationalists in<br />

Turkey’s ruling Justice <strong>and</strong> Development Party turn to Ottoman images not<br />

to illustrate <strong>the</strong> diversity <strong>of</strong> modern Turkey, but to stress <strong>the</strong> centrality <strong>of</strong> Islam<br />

in <strong>the</strong> secular state.<br />

Sébah & Joaillier (Turkish,<br />

active 1888–c. 1950),<br />

Panoramic View <strong>of</strong> Brousse,<br />

19th century. Albumen<br />

print. Gift <strong>of</strong> Joseph Folberg,<br />

1994.68.120<br />

10

THE GATE AND THE PYRAMID<br />

The <strong>the</strong>mes <strong>of</strong> nationalism <strong>and</strong> colonialism—building a nation at home <strong>and</strong><br />

exp<strong>and</strong>ing it abroad—were not separate or distinct in nineteenth-century photography.<br />

Often a single image or a portfolio <strong>of</strong> photographs could encompass<br />

both, as exemplified by a portfolio by a number <strong>of</strong> French <strong>and</strong> Italian photographers<br />

entitled Views <strong>of</strong> France, Algeria, <strong>and</strong> Italy, acquired by <strong>the</strong> Cantor Arts<br />

Center in 1980. The portfolio, which contains nineteen images taken between<br />

1875 <strong>and</strong> 1890, collapses <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> a tour <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mediterranean into<br />

a volume small enough to display at a dinner party. Through its images a<br />

viewer visits <strong>the</strong> ruins <strong>of</strong> Pompeii, sees <strong>the</strong> artistic marvels <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Vatican (with<br />

reproductions <strong>of</strong> a scene <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> martyrdom <strong>of</strong> Saint Sebastian by <strong>the</strong> painter<br />

Guido Reni <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> famed classical sculpture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Trojan Laocoön <strong>and</strong> his<br />

sons writhing beneath <strong>the</strong> bodies <strong>of</strong> sea serpents), <strong>and</strong> takes in sweeping views<br />

<strong>of</strong> urban life.<br />

The portfolio opens with an image <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bay <strong>of</strong> Marseille, <strong>the</strong>n bounces<br />

between sundrenched French cityscapes <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> romanticized ruins <strong>of</strong> ancient<br />

civilizations in Algeria. These <strong>the</strong>mes merge in images <strong>of</strong> Italy, which <strong>the</strong><br />

portfolio depicts as a kind <strong>of</strong> hybrid <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two: <strong>the</strong> roots <strong>of</strong> European identity<br />

shaped by foreign forces <strong>of</strong> history. A photograph by <strong>the</strong> Italian studio<br />

Fratelli d’Aless<strong>and</strong>ri <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Porta San Paolo in Rome depicts architectural<br />

marvels from two different eras side-by-side: a third-century CE gate in <strong>the</strong><br />

Aurelian walls that protected <strong>the</strong> city <strong>of</strong> Rome, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pyramid <strong>of</strong> Cestius,<br />

an Egyptian-style pyramid built in 12 BCE as a tomb for a Roman magistrate<br />

(fig. 3). Both illustrate moments in <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> Rome. Built less than two<br />

decades after Mark Antony’s establishment <strong>of</strong> a Roman colony in Egypt, <strong>the</strong><br />

pyramid was once a monument to <strong>the</strong> sprawling reach <strong>of</strong> Roman culture <strong>and</strong><br />

power. The gate, by contrast, was constructed in <strong>the</strong> waning days <strong>of</strong> Roman<br />

imperial power as a defensive perimeter.<br />

The Fratelli d’Aless<strong>and</strong>ri image inverts <strong>the</strong>se histories, celebrating <strong>the</strong><br />

gate <strong>and</strong> walls as Roman <strong>and</strong> framing <strong>the</strong> pyramid as <strong>the</strong> edifice <strong>of</strong> a distant,<br />

foreign past. Vines climb <strong>the</strong> sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pyramid, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> crenellations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

gate appear to be crumbling. But while <strong>the</strong> former appears forbidding <strong>and</strong><br />

ancient, solid <strong>and</strong> visually impenetrable, <strong>the</strong> city <strong>of</strong> Rome glows through <strong>the</strong><br />

open porta. The open gate operates as a kind <strong>of</strong> visual bridge, <strong>the</strong> city just<br />

fig. 3<br />

Fratelli d’Aless<strong>and</strong>ri (Italian,<br />

active 1870s), 144. ROMA–<br />

Piramide di Cajo Cestio e<br />

Porta S. Paolo, c. 1875–90.<br />

Albumen print. Art Gallery<br />

<strong>and</strong> Museum General Gift,<br />

1980.102.1.12.b<br />

12

visible through its archway. The image elegantly demonstrates how <strong>the</strong> political<br />

project <strong>of</strong> nineteenth-century photography leveraged <strong>the</strong> monuments <strong>of</strong><br />

history. The photograph simultaneously depicts <strong>the</strong> glorious past that frames<br />

a modern nation (<strong>the</strong> glowing city through <strong>the</strong> gateway) <strong>and</strong> a foreign o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

trapped in <strong>the</strong> past (<strong>the</strong> vine-covered pyramid). Although both are monuments<br />

<strong>of</strong> Roman history, <strong>the</strong>y are portrayed as two different pasts—one foreign<br />

<strong>and</strong> one domestic—only one <strong>of</strong> which leads to <strong>the</strong> present.<br />

13

DEPICTING A UNIFIED ITALY<br />

Italy’s history <strong>and</strong> artistic legacy had long made it a destination for French <strong>and</strong><br />

British artists who wished to study <strong>the</strong> ancient world within a safely European<br />

setting. In 1663 France’s King Louis XIV established <strong>the</strong> Gr<strong>and</strong> Prix de Rome,<br />

an annual prize awarded to painters <strong>and</strong> sculptors to travel to Italy to study <strong>the</strong><br />

legacies <strong>of</strong> classical antiquity <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Renaissance. In <strong>the</strong> eighteenth <strong>and</strong> early<br />

nineteenth centuries, members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> English upper class, <strong>and</strong> more than a few<br />

Americans, embarked on what became known as <strong>the</strong> Gr<strong>and</strong> Tour, traveling<br />

around <strong>the</strong> European continent, <strong>and</strong> particularly across <strong>the</strong> Italian peninsula, to<br />

study <strong>the</strong> monuments <strong>of</strong> classical <strong>and</strong> neoclassical art <strong>and</strong> culture.<br />

Artists <strong>and</strong> printmakers catered to <strong>the</strong> tastes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Gr<strong>and</strong> Tourists by<br />

making stylized souvenir views, known as vedute. An ink sketch by <strong>the</strong> Italian<br />

fig. 4<br />

Carlo Labruzzi (Italian,<br />

1748–1817), Ruins in <strong>the</strong><br />

Roman Forum, c. 1790. Ink<br />

on paper. Committee for Art<br />

Acquisitions Fund, 1974.208<br />

14

fig. 5<br />

Gaetano Pedo Studio<br />

(Italian, active 1880–90), The<br />

Roman Forum, Rome (Roma,<br />

Foro Romano), 19th century.<br />

Albumen print. Museum<br />

Purchase Fund, 1973.63.2<br />

artist Carlo Labruzzi made circa 1790, for example, depicts three men in togas<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ing amid <strong>the</strong> Roman Forum (fig. 4) Labruzzi’s scene conflates <strong>the</strong> Forum<br />

as a Gr<strong>and</strong> Tourist would have found it—largely in a state <strong>of</strong> ruin—with living,<br />

breathing figures <strong>of</strong> ancient Rome, as though <strong>the</strong> same senators who occupied<br />

<strong>the</strong> Forum in Caesar’s day still w<strong>and</strong>ered <strong>the</strong>re.<br />

A photograph <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same ruins by <strong>the</strong> nineteenth-century photography<br />

studio <strong>of</strong> Gaetano Pedo steps back, depicting <strong>the</strong> Forum in <strong>the</strong> foreground<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> city in <strong>the</strong> background behind it (fig. 5). Beyond <strong>the</strong> picturesque<br />

ruins rises <strong>the</strong> Palazzo Senatorio, built in <strong>the</strong> thirteenth century—largely from<br />

stones taken from <strong>the</strong> ruins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Forum—to house <strong>the</strong> Roman senate. The<br />

palazzo to this day is <strong>the</strong> seat <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Roman city council. Beyond that are <strong>the</strong><br />

15

apartments <strong>and</strong> commercial buildings <strong>of</strong> urban Rome. In Pedo’s image, Rome<br />

is hardly a city <strong>of</strong> toga-clad ghosts; it is a modern city with a lengthy history<br />

built upon, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten even from, its imperial foundation.<br />

Until 1861, when Italy was declared a unified nation under King Vittorio<br />

Emanuele II with Rome as its capital, <strong>the</strong> Italian peninsula had consisted <strong>of</strong> a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> separate republics, states, kingdoms, <strong>and</strong> duchies, each with a proud<br />

<strong>and</strong> distinct history. The gradual process <strong>of</strong> unification, known in Italian as<br />

<strong>the</strong> Risorgimento, had a precursor. During <strong>the</strong> Napoleonic wars <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1810s,<br />

Napoleon had conquered much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> peninsula <strong>and</strong> sought to unify it under<br />

a French governor. Keen to distinguish his own rule from that <strong>of</strong> a foreign<br />

power, Vittorio Emanuele sought to highlight <strong>the</strong> common cultural ancestry<br />

<strong>of</strong> his new state. He commissioned photographers, including <strong>the</strong> Alinari bro<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

in Florence <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> German expatriate Giorgio Sommer in Naples, to<br />

document <strong>and</strong> promulgate <strong>the</strong> patrimony <strong>of</strong> Italy as a shared cultural history.<br />

Sommer, several <strong>of</strong> whose photographs are included in <strong>the</strong> Cantor portfolio,<br />

took a particular interest in <strong>the</strong> ongoing excavations at Pompeii, <strong>the</strong><br />

Roman city near Naples buried by <strong>the</strong> eruption <strong>of</strong> Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE<br />

<strong>and</strong> preserved beneath <strong>the</strong> volcanic ash (fig. 6). 5 Sommer’s image renders <strong>the</strong><br />

ruins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> central basilica (Pompeii’s central administrative complex, built<br />

in <strong>the</strong> second century BCE) against Mount Vesuvius in <strong>the</strong> background. The<br />

excavated city is neat <strong>and</strong> orderly, its streets wide <strong>and</strong> empty, <strong>the</strong> dark dirt<br />

punctuated by <strong>the</strong> stark white <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> few surviving marble floor tiles <strong>of</strong> what<br />

was once a massive complex. Column bases, <strong>the</strong>ir shafts cut <strong>of</strong>f abruptly at<br />

uneven heights, recede into <strong>the</strong> background. Sommer took <strong>the</strong> image from an<br />

elevated position, st<strong>and</strong>ing on <strong>the</strong> raised platform at <strong>the</strong> basilica’s end—what<br />

would have been <strong>the</strong> seat <strong>of</strong> civic power in Roman times. The fine patterning<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brickwork, which once would have been covered with sheets <strong>of</strong> gleaming<br />

marble, is visible, as are <strong>the</strong> intricate networks <strong>of</strong> veins in <strong>the</strong> stone <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

surviving plinths <strong>and</strong> slabs. In <strong>the</strong> distance Vesuvius looms, dark <strong>and</strong> silently<br />

smoldering. Sommer’s camera, which captures <strong>the</strong> details <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> excavation in<br />

precise detail, renders <strong>the</strong> volcano simply as a hulking mass, <strong>the</strong> steam from its<br />

peak dissipating into <strong>the</strong> clouds.<br />

In a painting created a half-century earlier by Théodore Caruelle<br />

d’Aligny, a French painter who traveled <strong>of</strong>ten to Naples, a bored Gr<strong>and</strong> Tourist<br />

slumps against a low wall above <strong>the</strong> Bay <strong>of</strong> Naples while Vesuvius’s steam<br />

16

fig. 6<br />

Giorgio Sommer<br />

(Italian, born in Germany,<br />

1834–1914), 1202 Pompei,<br />

c. 1875–90. Albumen print.<br />

Art Gallery <strong>and</strong> Museum<br />

General Gift, 1980.102.1.7.b<br />

17

ises in <strong>the</strong> background (fig. 7). The scene is distinctly Italian only by dint <strong>of</strong><br />

Vesuvius’s subtle cameo; <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape is o<strong>the</strong>rwise nonspecific. But whereas<br />

d’Aligny includes Vesuvius as a kind <strong>of</strong> quote, a simple assertion that <strong>the</strong> body<br />

<strong>of</strong> water is indeed <strong>the</strong> Bay <strong>of</strong> Naples, Sommer’s remarkably similar-looking<br />

Vesuvius appears as a kind <strong>of</strong> foe, a lingering threat not only to Pompeii but to<br />

<strong>the</strong> century <strong>of</strong> effort <strong>and</strong> research devoted to excavating its remains.<br />

A photograph taken in <strong>the</strong> 1870s by <strong>the</strong> Florentine Giacomo Brogi from<br />

fig. 7<br />

Théodore Caruelle d’Aligny<br />

(French, 1798–1871), View<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bay <strong>of</strong> Naples, c. 1834.<br />

Oil on canvas. Committee<br />

for Art Acquisitions Fund,<br />

1978.164<br />

18

fig. 8<br />

Giacomo Brogi (Italian,<br />

1822–1881), View <strong>of</strong> Naples<br />

from Tolentino, 19th century.<br />

Albumen print. Gift <strong>of</strong><br />

Joseph Folberg, 1994.85.11<br />

nearly <strong>the</strong> same vantage point as d’Aligny’s painting echoes Sommer’s assertion<br />

that Vesuvius is far more than mere set dressing (fig. 8). Gone is <strong>the</strong> bored<br />

tourist, <strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong>ir place is <strong>the</strong> sweeping expanse <strong>of</strong> Naples itself. Sommer’s<br />

<strong>and</strong> Brogi’s images make clear both <strong>the</strong> stakes <strong>of</strong> Vesuvius’s threat <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

proud defiance <strong>of</strong> those who live in its shadow. Sommer’s Pompeii is not a<br />

haunted ruin but pro<strong>of</strong> that a civilization once flourished against <strong>the</strong> backdrop<br />

<strong>of</strong> Vesuvius’s constant threat. Brogi’s Naples is pro<strong>of</strong> that one still does.<br />

19

Fratelli Alinari<br />

In 1852 <strong>the</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>rs Leopoldo, Giuseppe, <strong>and</strong> Romualdo Alinari founded a<br />

photography studio in Florence dedicated to documenting <strong>the</strong> artworks <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> city’s churches, museums, <strong>and</strong> civic buildings. Their success at producing<br />

precise <strong>and</strong> detailed images <strong>of</strong> frescoes, sculptures, mosaics, <strong>and</strong> architectural<br />

elements led to a commission by King Vittorio Emanuele II to exp<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

scope <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir work to encompass all <strong>of</strong> newly unified Italy. This royal assignment<br />

afforded Fratelli Alinari access to aspects <strong>of</strong> Italy’s artistic <strong>and</strong> architectural<br />

heritage that would be impossible for an ordinary tourist to visit, as in this<br />

photograph, taken from <strong>the</strong> ro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> Milan’s ca<strong>the</strong>dral.<br />

In addition to working with <strong>the</strong> nascent Italian state, Fratelli Alinari<br />

also sold prints <strong>and</strong> glass plate slides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir photographs to academics across<br />

<strong>the</strong> world, particularly art historians who used <strong>the</strong>m to illustrate publications<br />

<strong>and</strong> slide lectures. The reach <strong>and</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir images is still felt across<br />

academia; more than a hundred <strong>and</strong> fifty years later, <strong>the</strong> company remains one<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> largest sources <strong>of</strong> high-resolution images <strong>of</strong> Italian artworks. Through<br />

Fratelli Alinari, Vittorio Emanuele II’s documentary campaigns <strong>of</strong> Italian patrimony<br />

influenced not only how Italians see <strong>the</strong>ir own nation, but how scholars<br />

around <strong>the</strong> world see Italy <strong>and</strong> its history.<br />

Fratelli Alinari (Italian, active<br />

1854–1920), The Ca<strong>the</strong>dral<br />

<strong>of</strong> Milan (Duomo di Milano),<br />

19th century. Albumen<br />

print. Gift <strong>of</strong> Joseph Folberg,<br />

1994.85.3<br />

20

PHOTOGRAPHING GOTHIC ENGLAND<br />

While Italy’s photographers sought to highlight <strong>the</strong> shared history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir new<br />

nation, in Britain <strong>the</strong>y took to <strong>the</strong> countryside to depict <strong>the</strong>ir nation as it once<br />

had been. As <strong>the</strong> Industrial Revolution swept through Engl<strong>and</strong>, Scotl<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong><br />

Wales, <strong>the</strong> once heavily agrarian rural economy rapidly urbanized. Workers<br />

moved in droves to cities, where <strong>the</strong>y lived in dense <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten dangerous<br />

conditions, close to <strong>the</strong> factories <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> mills that employed <strong>the</strong>m. Many,<br />

particularly artists <strong>and</strong> architects, opposed this rapid urban growth, decrying<br />

poverty <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> cramped, unsafe living conditions it forced upon laborers.<br />

In 1836 <strong>the</strong> architect Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin published a pamphlet<br />

<strong>of</strong> prints unfavorably comparing Engl<strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong> 1830s with Engl<strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong><br />

1530s. Called Contrastes, it promoted <strong>the</strong> Middle Ages as a time <strong>of</strong> plenty, elegant<br />

Gothic architecture, <strong>and</strong> independent workers skilled in a variety <strong>of</strong> crafts—<br />

radically distinct from <strong>the</strong> Industrial Revolution, <strong>the</strong> era <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poorhouse, <strong>the</strong><br />

unsanitary city, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> bored worker toiling over an automated loom. New<br />

architecture evoking <strong>the</strong> pointed arches <strong>and</strong> intricate stained glass <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Late<br />

Middle Ages had been popular in elite circles for several decades, but Pugin’s<br />

Contrastes proposed something different: that a Gothic revival could be at once<br />

an architectural <strong>and</strong> a social movement, a return to what he perceived as an idyllic<br />

medieval past. Commissioned in 1835, along with Charles Barry, to reconstruct<br />

fig. 9<br />

Artist unknown (English),<br />

Westminster Palace (Parliament<br />

Blgs), from Views in Europe<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States,<br />

1875–80. Albumen print.<br />

Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. George Liddle,<br />

1977.207.1.a<br />

22

fig. 10<br />

Artist unknown (English),<br />

The Old Rod Yard, Ely,<br />

c. 1880. Carbon print<br />

possibly. Gift <strong>of</strong> Joseph<br />

Folberg, 1994.68.17<br />

<strong>the</strong> Palace <strong>of</strong> Westminster in London (<strong>the</strong> meeting place <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Houses <strong>of</strong><br />

Parliament) after a fire destroyed it in 1834, Pugin designed <strong>the</strong> seat <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people’s<br />

power in Engl<strong>and</strong> as a many-spired Gothic castle (fig. 9). Reproducing <strong>the</strong><br />

aes<strong>the</strong>tics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle Ages, he hoped, would revive its ethos as well.<br />

As Pugin, alongside <strong>the</strong>orists like John Ruskin <strong>and</strong> designers like William<br />

Morris, promoted <strong>the</strong> Gothic Revival as <strong>the</strong> antidote to <strong>the</strong> ills <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> industrialized<br />

city, photographers around Engl<strong>and</strong> sought to dramatize <strong>the</strong> beauty<br />

<strong>and</strong> majesty <strong>of</strong> Engl<strong>and</strong>’s surviving medieval Gothic monuments. In Ely, a city<br />

in <strong>the</strong> swampy eastern fenl<strong>and</strong>, far from <strong>the</strong> industrial centers <strong>of</strong> Manchester,<br />

London, <strong>and</strong> Leeds, an anonymous photographer captured a scene <strong>of</strong> bucolic<br />

rural industry: basket weavers unloading sheaves <strong>of</strong> willow at a riverbank (fig. 10).<br />

In <strong>the</strong> background, <strong>the</strong> almost spectral presence <strong>of</strong> Ely’s monumental fourteenthcentury<br />

ca<strong>the</strong>dral watches over <strong>the</strong> laborers. From <strong>the</strong> flat-bottomed boat <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

reed ga<strong>the</strong>rers, to <strong>the</strong> picturesque pub at <strong>the</strong> shore, with its partially thatched<br />

23

o<strong>of</strong>, to <strong>the</strong> haunting ca<strong>the</strong>dral in <strong>the</strong> background, <strong>the</strong> scene could practically<br />

be <strong>the</strong> 1530s. None <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> modern drainage systems <strong>and</strong> levees that protected<br />

<strong>the</strong> low-lying town or <strong>the</strong> smokestacks <strong>of</strong> Ely’s ceramics industry are visible,<br />

nor is it clear from <strong>the</strong> image that <strong>the</strong> sheaves <strong>the</strong> workers hoist are bound for<br />

John Fear Basket Manufacturer <strong>and</strong> Rod Merchant, an industrial basket factory.<br />

<strong>Photography</strong>, with its promise <strong>of</strong> exquisite reality, casts as true a scene just as<br />

imaginary as Pugin’s mythologized sixteenth century.<br />

Not all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> photographers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Gothic Revival headed for <strong>the</strong> fens<br />

in search <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> idyllic Middle Ages. Whereas Pugin had imagined <strong>the</strong> Gothic as<br />

a lost <strong>and</strong> romantic past, o<strong>the</strong>rs sought to render <strong>the</strong> Gothic as part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fabric<br />

<strong>of</strong> modern Engl<strong>and</strong>—a cultural force that still shaped <strong>the</strong> nation. For both camps,<br />

Gothic architecture was more than simply a stylistic choice. Pugin, like many <strong>of</strong><br />

his supporters, was Catholic <strong>and</strong> closely tied <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> medieval nobility to <strong>the</strong><br />

establishment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Church <strong>of</strong> Engl<strong>and</strong>. It was no accident that Pugin located<br />

his idealized Middle Ages in 1530, six years before Henry VIII’s conversion <strong>and</strong><br />

his subsequent destruction <strong>of</strong> many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same rural monasteries that Pugin<br />

imagined <strong>and</strong> illustrated.<br />

For o<strong>the</strong>rs, however, towering Gothic churches were pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> a vital cultural<br />

history <strong>of</strong> engineering <strong>and</strong> skilled artisanship more than <strong>the</strong>y represented<br />

institutions <strong>of</strong> faith. Francis Frith, for example, framed Lincoln ca<strong>the</strong>dral—<br />

built over nearly two <strong>and</strong> a half centuries beginning in 1311—as <strong>the</strong> backdrop<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> modern city <strong>of</strong> Lincoln (fig. 11). The ca<strong>the</strong>dral’s façade fills <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong><br />

an empty, architecturally diverse street. The rusticated blocks <strong>and</strong> bricks <strong>of</strong> a<br />

Georgian mansion abut <strong>the</strong> stucco façade <strong>of</strong> a medieval timber-framed house.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> middle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> wide street an oil lamp st<strong>and</strong>s, its bulbous shape a modern<br />

counterpoint to <strong>the</strong> ca<strong>the</strong>dral’s spires. A small section <strong>of</strong> scaffolding that<br />

frames an element <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> church’s façade completes <strong>the</strong> scene: <strong>the</strong> ca<strong>the</strong>dral is<br />

rendered as a continuous project, a living part <strong>of</strong> Lincoln. The scene reiterates<br />

a visual hypo<strong>the</strong>sis advanced by <strong>the</strong> photographer William Henry Fox Talbot<br />

fifteen years earlier (fig. 12). Fox Talbot’s image, entitled A Scene in York, was<br />

part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> initial portfolio <strong>of</strong> images he used to promote his refinements to<br />

<strong>the</strong> craft <strong>of</strong> photography. In that photograph, York Minster rises ghostlike from<br />

<strong>the</strong> modern city. If Fox Talbot quietly proposed <strong>the</strong> Gothic ca<strong>the</strong>dral <strong>and</strong> its<br />

medieval associations as still lingering behind <strong>the</strong> growth <strong>of</strong> urban Engl<strong>and</strong>,<br />

Frith’s image framed <strong>the</strong> Gothic as its very core.<br />

24

fig. 11<br />

Francis Frith (English,<br />

1822–1898), Lincoln Ca<strong>the</strong>dral,<br />

c. 1860. Albumen print.<br />

Gift <strong>of</strong> Joseph Folberg,<br />

1994.68.68<br />

fig. 12<br />

William Henry Fox Talbot<br />

(English, 1800–1877),<br />

A Scene in York, 1845.<br />

Calotype. Committee for Art<br />

Acquisitions Fund, 1988.41<br />

25

The Ruin<br />

John Patrick (English, 1830–<br />

1923), Chapel Royal, Holyrood,<br />

19th century. Albumen<br />

print. Gift <strong>of</strong> Joseph Folberg,<br />

1994.68.100<br />

In nineteenth-century Britain, many monuments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle Ages were<br />

not towering edifices or glorious ca<strong>the</strong>drals, but ruins. In <strong>the</strong> sixteenth century,<br />

when Henry VIII broke from <strong>the</strong> Roman Catholic Church, his soldiers<br />

ransacked many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rural Catholic churches that refused to join his Church<br />

<strong>of</strong> Engl<strong>and</strong>. Called <strong>the</strong> Dissolution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Monasteries, <strong>the</strong> period resulted in<br />

<strong>the</strong> royal seizure <strong>of</strong> monastic holdings <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> widespread destruction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

medieval buildings.<br />

As Romanticism, <strong>the</strong> artistic movement that emphasized <strong>the</strong> awe <strong>and</strong><br />

power <strong>of</strong> time <strong>and</strong> nature, swept across Europe in <strong>the</strong> early nineteenth century,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se ruins were regarded as perfect representations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ravages <strong>of</strong> time, <strong>the</strong><br />

mistakes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> past, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> lost faith <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle Ages. Catholic groups<br />

in Engl<strong>and</strong>, like <strong>the</strong> popular Oxford Movement, treated images <strong>of</strong> ruins as<br />

testimony to <strong>the</strong> violent suppression <strong>of</strong> Catholicism by an oppressive ruler.<br />

But even Protestants <strong>and</strong> nonbelievers found beauty <strong>and</strong> mystery in <strong>the</strong>ir overgrown<br />

walls <strong>and</strong> crumbling stones. Yet o<strong>the</strong>rs viewed <strong>the</strong> ruins as Augustus<br />

Welby Northmore Pugin had in his Contrastes: as evidence <strong>of</strong> a prosperous,<br />

agrarian medieval society that had been undone by greed <strong>and</strong> force. Ruins<br />

became so central to <strong>the</strong> nineteenth-century popular cultural imaginary that<br />

architects were commissioned to design fake ruins, known as follies, for <strong>the</strong><br />

estates <strong>of</strong> wealthy families.<br />

The ruined chapel on <strong>the</strong> Scottish royal estate <strong>of</strong> Holyrood was not<br />

destroyed by Henry VIII’s armies but by a ro<strong>of</strong> collapse in <strong>the</strong> eighteenth century.<br />

Ab<strong>and</strong>oned by <strong>the</strong> Scottish royal court, <strong>the</strong> structure was deemed too<br />

costly to repair. Never<strong>the</strong>less, John Patrick’s photograph <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> building exemplifies<br />

<strong>the</strong> Romantic tradition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ruin: <strong>the</strong> nave open to <strong>the</strong> sky, <strong>the</strong> stone<br />

tracery <strong>of</strong> a window visible but <strong>the</strong> glass long gone. Although images like<br />

Patrick’s are rooted in a particular historical <strong>and</strong> political context, <strong>the</strong>ir influence<br />

has far outlasted <strong>the</strong> Gothic Revival or Romanticism. Contemporary<br />

photography <strong>of</strong> ruins proliferates on platforms like Instagram. Its popularity<br />

spurs photographers <strong>and</strong> would-be influencers to document everything from<br />

ab<strong>and</strong>oned suburban tract housing to ghost towns in <strong>the</strong> Western United States<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, in search <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> crumbling, overgrown,<br />

Romantic picturesque.<br />

27

28

fig. 13<br />

Isidore Justin Taylor with<br />

Charles Nodier <strong>and</strong><br />

Alphonse de Cailleux<br />

(Isidore Justin Taylor:<br />

French, born in Belgium,<br />

1789–1879; Charles Nodier:<br />

French, 1780–1844; Alphonse<br />

de Cailleux: French,<br />

1788–1876), Vue générale de<br />

la gr<strong>and</strong> Cathédrale d’Evreux,<br />

from Voyages pittoresques et<br />

romantiques dans l’ancienne<br />

France, Volume I, 1820.<br />

Illustrated book with<br />

lithographs. National<br />

Library <strong>of</strong> France<br />

THE MISSION HÉLIOGRAPHIQUE<br />

In early nineteenth-century France, however—seesawing between revolutionary<br />

governments <strong>and</strong> strong-armed rulers—<strong>the</strong> monuments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle<br />

Ages were more politically fraught. In Paris, many antiquarians sought to celebrate<br />

medieval France just as Frith did medieval Engl<strong>and</strong>, casting <strong>the</strong> era <strong>and</strong><br />

its monuments as a source <strong>of</strong> national identity. In 1820 three men—<strong>the</strong> baron<br />

Isidore Justin Taylor, <strong>the</strong> viscount Alphonse de Cailleux, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> académicien<br />

Charles Nodier—began a series <strong>of</strong> densely illustrated books, which <strong>the</strong>y<br />

termed Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France (Picturesque <strong>and</strong><br />

Romantic Journeys in Ancient France, fig. 13). Their narrative, like Pugin’s,<br />

was a history <strong>of</strong> kindly rulers <strong>and</strong> noblesse oblige, illustrated with lithographic<br />

prints <strong>of</strong> architectural monuments as testaments to <strong>the</strong> power <strong>and</strong> gr<strong>and</strong>eur <strong>of</strong><br />

noble families <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> institutional Church.<br />

Their picturesque voyages were popular with <strong>the</strong> Parisian elites, but many<br />

who lived in <strong>the</strong> shadow <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monuments that Taylor, Nodier, <strong>and</strong> de Cailleux<br />

celebrated saw <strong>the</strong> buildings instead as legacies <strong>of</strong> a feudal past—remnants <strong>of</strong><br />

a period <strong>of</strong> power-hungry kings, abusive feudal lords, <strong>and</strong> a domineering<br />

Church. Churches, monasteries, <strong>and</strong> medieval civic buildings were being<br />

demolished by French governors <strong>and</strong> mayors who wanted to give <strong>the</strong>ir towns<br />

a clean break from <strong>the</strong> past. In 1830, when <strong>the</strong> July Revolution overthrew <strong>the</strong><br />

Bourbon monarchy, cities <strong>and</strong> towns across France began a wholesale campaign<br />

<strong>of</strong> renovation <strong>and</strong> reconstruction, re-creating <strong>the</strong>se “feudal” monuments<br />

as modern structures for modern purposes: converting parish churches into<br />

city halls, feudal prisons into Palais du Justice. A year later, <strong>the</strong> poet <strong>and</strong> novelist<br />

Victor Hugo published Notre-Dame de Paris (<strong>of</strong>ten titled The Hunchback<br />

<strong>of</strong> Notre-Dame in English translations), <strong>the</strong> story <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> enchanting gypsy<br />

Esmerelda, <strong>the</strong> hunchbacked bell ringer Quasimodo who loves her, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

corrupt archdeacon Claude Frollo. The novel plays out against <strong>the</strong> backdrop<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ca<strong>the</strong>dral <strong>of</strong> Notre-Dame in Paris, whose crumbling beauty <strong>and</strong> proud<br />

history Hugo analogizes to his disfigured but brave protagonist Quasimodo.<br />

Hugo’s novel describes architecture as <strong>the</strong> pure expression <strong>of</strong> society, a kind<br />

<strong>of</strong> poetry in stone. Hugo followed his immensely popular novel with an 1832<br />

essay entitled “Guerre aux démolisseurs” (War on <strong>the</strong> Demolishers), in which<br />

he called for new laws to protect French historical monuments. These edifices,<br />

he argued, are <strong>the</strong> story <strong>of</strong> France, echoing <strong>the</strong> claims <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> English Gothic<br />

29

evivalists that sites <strong>of</strong> architectural patrimony are not legacies <strong>of</strong> oppression<br />

but repositories <strong>of</strong> collective history. 6 Until <strong>the</strong> invention <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> printing press<br />

made literature accessible, Hugo argued, architecture was <strong>the</strong> primary means<br />

by which culture was preserved <strong>and</strong> kept alive.<br />

Hugo’s call for legal protection for monuments <strong>and</strong> historical buildings<br />

resulted in <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Commission des monuments historiques;<br />

his friend, <strong>the</strong> novelist <strong>and</strong> playwright Prosper Mérimée, was<br />

appointed its director. In 1851 <strong>the</strong> commission sent five artists, all members<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Société Héliographique, in five directions across France to document<br />

<strong>the</strong> nation’s architectural patrimony—an assignment known as <strong>the</strong> Mission<br />

Héliographique. 7 Romantic literature—including <strong>the</strong> novels <strong>of</strong> Hugo <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

plays <strong>of</strong> Mérimée—was not far from <strong>the</strong> minds <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> five, <strong>and</strong> its influence is<br />

strongly felt in <strong>the</strong> photographs from <strong>the</strong>ir survey.<br />

Charles Soulier, for example, framed Notre-Dame from across <strong>the</strong><br />

Seine in winter, <strong>the</strong> church’s narrow flying buttresses rising like tendrils from a<br />

smoky grove <strong>of</strong> trees (fig. 14). Édouard Denis Baldus photographed <strong>the</strong> Maison<br />

Carrée, <strong>the</strong> first-century CE Roman temple in Nîmes that was <strong>the</strong> inspiration<br />

for Paris’s Église de la Madeleine <strong>and</strong> Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia State Capitol,<br />

from an oblique angle, ignoring <strong>the</strong> hyper-rational geometry <strong>of</strong> its square<br />

façade <strong>and</strong> rendering <strong>the</strong> famously white marble as dark, <strong>and</strong> its portico cast<br />

in shadow (fig. 15). By framing <strong>the</strong> scene from askance, <strong>the</strong> temple’s repeating<br />

columns echo <strong>the</strong> rhythm <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fence posts that separate <strong>the</strong> monument from<br />

<strong>the</strong> street before it, <strong>and</strong> its outline is interrupted by a single st<strong>and</strong>ing oil lamp.<br />

In Baldus’s image, <strong>the</strong> light—ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> intellectual light <strong>of</strong> history, or <strong>the</strong><br />

reflected gleam <strong>of</strong> marble—comes not from <strong>the</strong> building. Instead, illumination<br />

comes from <strong>the</strong> simple oil lamp, <strong>the</strong> product <strong>of</strong> civic services tended by an<br />

unseen laborer. Just as in Hugo’s novel, architecture becomes <strong>the</strong> backdrop for<br />

a story <strong>of</strong> modern French life.<br />

Light is also <strong>the</strong> primary language <strong>of</strong> a photograph <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> interior <strong>of</strong><br />

Rouen Ca<strong>the</strong>dral taken by <strong>the</strong> Bisson bro<strong>the</strong>rs studio (fig. 16). Shot from an<br />

elevated position anchored to <strong>the</strong> right-side wall <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> church’s fourteenthcentury<br />

nave, <strong>the</strong> image gazes toward <strong>the</strong> apse <strong>and</strong> high altar. Hazy light<br />

casts long horizontal shadows from <strong>the</strong> unseen windows <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nave, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

apse’s windows glow. The height <strong>and</strong> delicacy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stone pillars, culminating<br />

in steeply pointed archways, gives <strong>the</strong> architecture <strong>the</strong> evanescent quality<br />

30

fig. 14<br />

Charles Soulier (French,<br />

1840–1875), Notre-Dame<br />

de Paris, c. 1860. Albumen<br />

print. Committee for Art<br />

Acquisitions Fund, 1986.122<br />

fig. 15<br />

Édouard Denis Baldus<br />

(French, c. 1813–c. 1882),<br />

The Maison Carrée, Nîmes,<br />

1853. Albumen print. Gift <strong>of</strong><br />

William Rubel, 1994.170<br />

31

<strong>of</strong> fine lace hovering in a breeze. 8 The interior is<br />

completely empty save for two chairs, which sit<br />

like props on a stage, waiting for <strong>the</strong> actors. The<br />

photograph doesn’t aim to represent <strong>the</strong> church in<br />

<strong>the</strong> light <strong>of</strong> scientific Enlightenment—as <strong>the</strong> revolutionaries<br />

in Paris who rechristened Notre-Dame<br />

as a secular temple to <strong>the</strong> Cult <strong>of</strong> Reason in 1793<br />

would have—nor as divinely lit <strong>and</strong> rooted purely<br />

in faith. Instead, it presents <strong>the</strong> Gothic structure as<br />

an architectural marvel deserving <strong>of</strong> preservation, to<br />

be lived with as a monument to <strong>the</strong> French history<br />

that created it.<br />

BUILDING THE NATION ABROAD<br />

While photography flourished across Europe as<br />

<strong>the</strong> visual language <strong>of</strong> nation building, Europe’s<br />

nations sought to exp<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir power beyond <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

historical borders. In 1830 French troops invaded<br />

Algeria, establishing a military-run government in <strong>the</strong> capital, Algiers, <strong>and</strong><br />

supply chains to ship Algerian goods to mainl<strong>and</strong> France. Across Africa <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Middle East in <strong>the</strong> years that followed, <strong>the</strong> British, French, Italian, Belgian,<br />

German, Spanish, <strong>and</strong> Portuguese governments seized territory for <strong>the</strong>mselves,<br />

stripping <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> its resources, fueling <strong>and</strong> exacerbating local rivalries <strong>and</strong><br />

conflicts for <strong>the</strong>ir own gain, <strong>and</strong> ruling <strong>the</strong>ir new territories with brutal martial<br />

force. European states <strong>of</strong>ten considered <strong>the</strong> countries <strong>the</strong>y seized, like Algeria,<br />

as simply new l<strong>and</strong> for <strong>the</strong> invading nation. Local cultures <strong>and</strong> histories were<br />

annihilated. In <strong>the</strong>ir place, European languages were taught, <strong>and</strong> European laws<br />

<strong>and</strong> cultural norms enforced.<br />

Paradoxically, just as foreign governors tried to efface <strong>the</strong> local history <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>the</strong>y seized, European artists were brought in droves to Africa <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Middle East to depict <strong>the</strong> monuments <strong>and</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se distant l<strong>and</strong>s. Unlike<br />

<strong>the</strong> Gothic Revivalists or <strong>the</strong> photographers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mission Héliographique,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se European artists <strong>and</strong> photographers sought to dramatize <strong>the</strong> mysterious<br />

exoticism <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir subjects. Their mythologizing images <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same histories<br />

that European governments suppressed were specifically intended to attract<br />

fig. 16<br />

Bisson Frères (Louis-Auguste<br />

Bisson: French,1814–1876;<br />

Auguste-Rosalie Bisson:<br />

French, 1826–1900), Rouen<br />

Ca<strong>the</strong>dral, Interior, c. 1860. Salt<br />

print. Gift from <strong>the</strong> Alinder<br />

Collection, 1988.156<br />

32

fig. 17<br />

Photoglob Zurich (Swiss,<br />

active 1880s–1900s), 15,024.<br />

P.Z.–Jérusalem. Mur des<br />

Lamentations, from Album<br />

<strong>of</strong> Photographs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Holy<br />

L<strong>and</strong> Assembled by Boulos<br />

Meo, Jerusalem, before 1901.<br />

Photochrom. Gift <strong>of</strong> Charles<br />

B. Leib, 1977.37.20<br />

would-be colonists to <strong>the</strong>se newly seized territories. 9 Africa became <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pharaohs <strong>and</strong> lions, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle East <strong>the</strong> Holy L<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> medieval lore.<br />

While European photographers depicted <strong>the</strong>ir home nations emerging from a<br />

common past, albeit an entirely constructed one, <strong>the</strong>y depicted <strong>the</strong>ir colonial<br />

quarries as trapped in a distant past that was equally imaginary. 10<br />

A photochrom—a colorized print—by <strong>the</strong> Swiss studio Photoglob<br />

Zurich epitomizes this trend (fig. 17). In <strong>the</strong> image, part <strong>of</strong> an album <strong>of</strong> photographs<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Holy L<strong>and</strong> owned by Jane Stanford, pilgrims, <strong>the</strong>ir bodies<br />

draped in prayer shawls, press <strong>the</strong>mselves against <strong>the</strong> Western Wall in Jerusalem,<br />

said to be <strong>the</strong> last surviving element <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sixth-century BCE temple built<br />

under <strong>the</strong> reign <strong>of</strong> Herod. Entitled Mur des lamentations (Wall <strong>of</strong> Lamentations)<br />

after <strong>the</strong> scraps <strong>of</strong> prayer that Jewish pilgrims leave in <strong>the</strong> cracks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancient<br />

33

limestone, <strong>the</strong> photograph renders <strong>the</strong> wall climbing up past <strong>the</strong> frame’s<br />

bounds <strong>and</strong> vines tumbling down its uneven surface. Supplicants bow <strong>and</strong><br />

kneel before <strong>the</strong> semi-ruin. To a French audience <strong>the</strong> scene would have been<br />

a stark contrast to <strong>the</strong> glowing light <strong>of</strong> Rouen ca<strong>the</strong>dral or <strong>the</strong> delicate spires<br />

<strong>of</strong> Notre-Dame. Soulier’s ghostly Notre-Dame rising from <strong>the</strong> haze <strong>of</strong> winter<br />

trees painted France’s national history as practically a natural element <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape, something always present that would always remain—an elegant<br />

backdrop to modern Paris. The Wall <strong>of</strong> Lamentations, by contrast, is cast as<br />

a history that still traps <strong>the</strong> Jerusalemites, despite <strong>the</strong> fact that in reality it is<br />

barely two hundred feet long <strong>and</strong> sixty feet high. The careful cropping makes<br />

it appear endless, a history that can never be overcome.<br />

Artists <strong>and</strong> writers like <strong>the</strong> painter Eugène Fromentin, who traveled<br />

to Algeria in 1852 as part <strong>of</strong> an archaeological expedition, depicted <strong>the</strong> vast<br />

desert l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>of</strong> newly colonized French North Africa as an enticement<br />

to adventurous French citizens who might travel to <strong>and</strong> settle in this new l<strong>and</strong><br />

tinged with dangers (fig. 18). But it was photographs, giving an impression <strong>of</strong><br />

unalloyed truth, that most vigorously captured <strong>the</strong> European colonial imagination<br />

(figs. 19, 20). Reviewing an album <strong>of</strong> photographs <strong>of</strong> Egypt taken in 1851<br />

by <strong>the</strong> French photographer Maxime du Camp, Francis Wey wrote:<br />

fig. 18<br />

Eugène Fromentin (French,<br />

1820–1876), The Desert at<br />

En-Furchi, Algeria, c. 1848.<br />

Charcoal <strong>and</strong> chalk. Alice<br />

Meyer Buck Fund, 1981.68<br />

34

fig. 19<br />

Photoglob Zurich (Swiss,<br />

active 1880s–1900s), Palace <strong>of</strong><br />

Justice, Casbah, Tangiers, 19th<br />

century. Photochrom. Gift <strong>of</strong><br />

Joseph Folberg, 1994.68.29<br />

fig. 20<br />

Wilhelm Hammerschmidt<br />

(German, c. 1830–1869),<br />

Bazaar, Cairo, c. 1860.<br />

Albumenized salt print from<br />

a paper negative. Gift <strong>of</strong><br />

Joseph Folberg, 1994.68.86<br />

35

It is powerfully unsettling to contemplate . . . all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sites <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> such a singular l<strong>and</strong> without suffering from <strong>the</strong> strangeness <strong>of</strong> its style <strong>and</strong><br />

character rendered in such intimate impressions <strong>of</strong> its reality. To enter into this<br />

album is to travel. The truth invades you, it strikes you, disrupts you in so many<br />

ways that soon you forget <strong>the</strong> print <strong>and</strong> its subjects are assimilated into your<br />

imagination <strong>and</strong> you begin to dream that you are following a caravan. For what<br />

is, after all, this l<strong>and</strong>? A vision, a mute tableau, an inert image <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> past. 11<br />

Just as Félix Bonfils depicted Cairo’s al-Qarafa as a direct link to <strong>the</strong><br />

distant past <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Abbasid Caliphate, Europeans across <strong>the</strong> colonies likewise<br />

depicted scenes <strong>of</strong> a distant past in <strong>the</strong> present: bazaars replete with camels,<br />

tents, <strong>and</strong> Bedouin traders, or buildings articulated with horseshoe arches<br />

<strong>and</strong> painted tiles. Whereas photographs <strong>of</strong> soaring Gothic spires or ancient<br />

Roman ruins represented <strong>the</strong> politicized histories <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir European nations,<br />

Europeans’ photographs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle East rendered garbled, mythologized<br />

histories <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nations that Europe sought to assimilate. If France’s past was <strong>the</strong><br />

geometric logic <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Maison Carrée <strong>and</strong> its present was <strong>the</strong> civic promise <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> oil lamp that beamed beside it, its future, <strong>the</strong>se images proposed to French<br />

audiences, was <strong>the</strong> untapped potential <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>s south <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mediterranean<br />

whose histories were yet to be “illuminated” by <strong>the</strong> light <strong>of</strong> modernization.<br />

Picturing <strong>the</strong>ir own colonialist <strong>and</strong> orientalizing vision <strong>of</strong> North Africa <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Middle East, photographers really illustrated <strong>the</strong>ir own nations—gazing at<br />

once lustily <strong>and</strong> fearfully across <strong>the</strong> Mediterranean.<br />

. . . MAIS IL FAUT LE CHOISIR<br />

It is tempting to look at many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se images now simply as historical relics,<br />

points along a history <strong>of</strong> photography that eventually arrived at <strong>the</strong> digital<br />

camera, <strong>the</strong> smartphone, <strong>the</strong> social media platform. But just as much as <strong>the</strong>se<br />

images represent a history <strong>of</strong> technology, <strong>the</strong>y depict a history <strong>of</strong> ideology<br />

whose legacy remains deeply rooted in how we make <strong>and</strong> consider images<br />

today. Today visual propag<strong>and</strong>a far more subtle <strong>and</strong> insidious than a carefully<br />

framed albumen print shapes how we conceive <strong>of</strong> our nations, our politics, <strong>and</strong><br />

our world. We know to scrutinize an image for <strong>the</strong> politician edited out <strong>of</strong> a<br />

compromising scene, <strong>the</strong> celebrity face superimposed onto a naked body. But<br />

36

it’s easy to forget that such extreme examples <strong>of</strong> doctored, fake images are only<br />

part <strong>of</strong> what makes a photograph misleading or untrue.<br />

“But it must be chosen,” Francis Wey’s addition to his journal’s motto,<br />

“Nothing is beautiful but <strong>the</strong> truth,” was intended to highlight <strong>the</strong> craft <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

photographer—<strong>the</strong>ir role in producing such an incredible likeness after life.<br />

But it actually presaged <strong>the</strong> biases <strong>and</strong> cultural prejudices that photographers<br />

brought to, <strong>and</strong> still bring to, <strong>the</strong>ir work. While in <strong>the</strong> nineteenth century<br />

photography remained <strong>the</strong> purview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> few—<strong>the</strong> rare artist wielding a<br />

camera—today we are all photographers. <strong>Photography</strong> gives us all <strong>the</strong> ability<br />

to choose what we depict as beautiful <strong>and</strong> what we depict as true. But what<br />

truth we see through a camera’s lens is precisely that: only what we see as <strong>the</strong><br />

truth. Although what we depict may not be <strong>the</strong> ideology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Italian state or<br />

<strong>the</strong> Ottoman sultan, it is just as much shaped by our own politics, ideas, hopes,<br />

<strong>and</strong> fears as any image <strong>of</strong> French patrimony or orientalized myth ever was.<br />

The technique that Wey breathlessly announced as <strong>the</strong> child <strong>of</strong> art <strong>and</strong> science,<br />

<strong>the</strong> apolitical medium that could render <strong>the</strong> honest beauty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world, is <strong>and</strong><br />

always has been a political tool.<br />

1. See Robert A. Sobieszek <strong>and</strong> E. S. Gavin Carney,<br />

Remembrances <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Near East: The Photographs <strong>of</strong><br />