You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Amantina</strong> <strong>Garcia</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Anacaona’s</strong> <strong>Stone</strong><br />

Today many Dominicans retain physical characteristics of their Taíno heritage--- so many in fact, that<br />

they are overlooked, just accepted as “Dominicans” except for those who are specifically looking for<br />

them - Dr Lynne Guitar<br />

May 29, 2013<br />

We arrived at San Juan de la Maguana during a heavy rain storm <strong>and</strong> head to Juan Herrera a<br />

small town 5 kilometers north of San Juan <strong>and</strong> where the so called “Corral de Los Indios” is located. The<br />

corral is an ancient ceremonial park where the Taino people played a<br />

ball game called batey. Located in the center of the town, it is the<br />

largest such park in the Caribbean, approximately 750 feet in<br />

diameter. At the center there is a large rock known as <strong>Anacaona’s</strong><br />

<strong>Stone</strong> with a small face etched on it. Local legend says that Cacique<br />

Anacaona would sit on this stone <strong>and</strong> recite her poetry or sing Areito<br />

songs during festivities.<br />

As part of the Caribbean Indigenous Legacies<br />

Project with the Smithsonian National Museum of the<br />

American Indian <strong>and</strong> the Smithsonian Latino Center, I<br />

was sent to this area to explore <strong>and</strong> document the<br />

indigeneity present in this <strong>and</strong> other parts of the Isl<strong>and</strong><br />

of Hispaniola (Haiti/Dominican Republic). Being a<br />

native of this isl<strong>and</strong> I am grateful for the opportunity to<br />

study this place. Along with me are photographer <strong>and</strong><br />

film maker Boynayel Mota, native activists MiltonVelasquez <strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Ivel Cenac, Leonel de Jesus Melo<br />

who heads an organization- Artesanos de Higuey <strong>and</strong> the lovely Caro Linka, a Mapuche Indian woman<br />

from Chile living on the Isl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Native Identity <strong>and</strong> traditions are taken seriously in this region as many people are Indian<br />

identified. It is also widely believed that Indian ancestral spirits inhabit the area, the rivers, caves <strong>and</strong><br />

trees. These beliefs are sustained by most of the inhabitants. However if you happen to encounter one of<br />

the countless Healers <strong>and</strong> Shaman that live in this area, they will gladly go into detail <strong>and</strong> elaborate on<br />

these customs. Maguana in general is a place where Taino, African <strong>and</strong> Spanish traditions blended in a<br />

unique <strong>and</strong> characteristically San Juan de la Maguana way.<br />

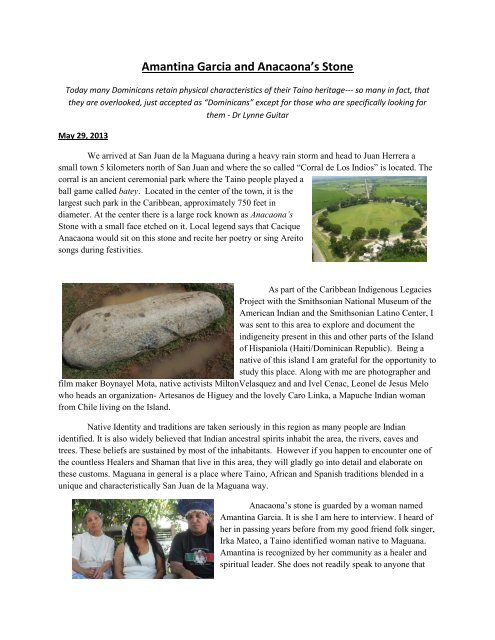

<strong>Anacaona’s</strong> stone is guarded by a woman named<br />

<strong>Amantina</strong> <strong>Garcia</strong>. It is she I am here to interview. I heard of<br />

her in passing years before from my good friend folk singer,<br />

Irka Mateo, a Taino identified woman native to Maguana.<br />

<strong>Amantina</strong> is recognized by her community as a healer <strong>and</strong><br />

spiritual leader. She does not readily speak to anyone that

just drops by to see her. Not because she refuses, but rather because she believes that <strong>Anacaona’s</strong> misterio<br />

(spirit) must instruct her to do so, otherwise <strong>Amantina</strong> will not engage visitors. After traveling such a long<br />

way, I now fear she may not want to see us. We arrive at her house just as the rain stops. My fears are<br />

quickly extinguished as she peers out of her home <strong>and</strong> says “You! I have waited so long for you to come!<br />

Anacaona was upset that you had not come to her. She is happy that you are finally here! Please come, sit<br />

with me, we have lots to speak about.” I am grateful yet perplexed <strong>and</strong> in all sincerity I am a little put off<br />

by her remark. During a previous trip to Mexico some years back, many Indigenous people would greet<br />

me in this way, but I always felt they did this due to an ulterior motive. <strong>Amantina</strong> is 70 years old but<br />

looks like she is in her 40s. She has the stereotypical Indian phenotype, long black hair, high cheek bones<br />

etc. We sit in front of her home as she offers us coffee <strong>and</strong> begins to tell us of <strong>Anacaona’s</strong> gr<strong>and</strong> plan.<br />

“This place is where our Queen Anacaona lives. She guides us <strong>and</strong> is connected to all the spiritual<br />

traditions of this area, the 21 Division (Dominican Vudu/ misterios), followers of Liborio Mateo <strong>and</strong><br />

practitioners of Agua Dulce, all come here to pay their respect to her. She is an Indian woman of the<br />

waters <strong>and</strong> the greatest of the mysteries (spirits) of this place” she says. “She is happy that you have<br />

finally arrived as there is much work to do. Our Queen needs a festival held in her name. It has to be<br />

strictly in honor of the Indian <strong>and</strong> at least once a year.”<br />

Maguana is known as the belly button<br />

of the world by the locals. It is also considered<br />

the spiritual center of the country. People<br />

travel from all over the isl<strong>and</strong> to pray here.<br />

There are daily pilgrimages to the area. In this<br />

place “Agua Dulce” (an Indigenous spiritual<br />

tradition) is strongest. A <strong>Stone</strong> cult <strong>and</strong> a<br />

Water cult are central to this tradition. <strong>Stone</strong>s<br />

are said to possess the power to cause visions.<br />

One of my contacts, Daniel Arias, an Agua<br />

Dulce practitioner explains, “Some stones<br />

such as quartz are said to produce as many as 5 visions(dreams) while other stones like jadeite (not true<br />

jadeite but a greenish marble-like stone) only give you three<br />

<strong>and</strong> so on.” He explains that certain ailments require one to<br />

travel through a series of dreams in order to locate the cause of<br />

the ailment. A person may require the aid of a stone that can<br />

produce a specific number of dreams in order to find his/her<br />

specific ailment within the dream <strong>and</strong> subsequently vanquish it.<br />

In healing practices stones , tobacco <strong>and</strong> medicinal plants are<br />

used in conjunction. <strong>Stone</strong>s are considered medicinal in this<br />

place. <strong>Amantina</strong> proudly shows us a stone she claims has<br />

traveled the world <strong>and</strong> has been used in numerous healing<br />

ceremonies.<br />

Another custom in this area is the “sun rise ceremony”<br />

described to me by Carmen Popa, a woman who follows the<br />

teachings of Papa Liborio (a Dominican Messianic figure). “At

sunrise communal stones are fed <strong>and</strong> watered <strong>and</strong> gratitude is expressed for the new day unfolding while<br />

simultaneously welcoming the sun.” These traditions are earnestly observed by followers <strong>and</strong> attention to<br />

detail is of the utmost importance. <strong>Anacaona’s</strong> stone is cared for in this exact way by <strong>Amantina</strong>. I could<br />

not help but notice the similarities between this custom <strong>and</strong> those reported by Spanish chroniclers. In fact<br />

the preoccupation with stones bears striking similarities with Cemism. In the Taino story of Guayahona<br />

<strong>and</strong> Guabonito recorded by Fray Ramon Pane there are many references to stones <strong>and</strong> their importance in<br />

Taino society. (1) In his book “Indios” Historian <strong>and</strong> former President of the Dominican Republic Juan<br />

Bosch writes “ These stones are preserved inside cotton. They (Taino) placed them in woven baskets <strong>and</strong><br />

watered <strong>and</strong> fed them as they did with the Cemi.” (2) <strong>Stone</strong>s have been a part of the isl<strong>and</strong>s religiosity<br />

long before European colonization.<br />

We ask for permission to visit the stone <strong>and</strong> <strong>Amantina</strong> offered this observation: “All of you go to<br />

the stone, but I will stay here. She has enough love for all of us, but I want her to embrace you without<br />

distraction from me.” I begin putting on a feathered headdress that I gifted to my wife years ago. My<br />

intention was to pay proper honor to this sacred space. As I put it on, <strong>Amantina</strong>’s eyes shone bright <strong>and</strong><br />

she says “yes it truly is you. You are the<br />

Cacique I was waiting for. I will go to the<br />

stone with you after all.” It seemed to me<br />

that from <strong>Amantina</strong>’s perspective, I<br />

symbolized an alley that could potentially<br />

help her in preserving this sacred space.<br />

Unknown to me at the time, there are plans<br />

by local officials to build a hotel atop this<br />

ancient ceremonial ground. Further,<br />

<strong>Anacaona’s</strong> stone that <strong>Amantina</strong>, her<br />

family <strong>and</strong> other villagers have cared for,<br />

for generations, will be placed in a yet to be built museum where the local worshipers will never again<br />

have access to it. On the way to the stone <strong>Amantina</strong> says “in this place if one sees a jaiba (crab) while<br />

praying, it is a sure sign that you have been visited by our Queen Anacaona.”<br />

Recorded local history tells us that as far back as 1913 a celebration honoring Anacaona was held<br />

in this place. During festivities men dressed as Indians would find <strong>and</strong> elect a beauty queen who looked<br />

Indian, crowned with a feathered headdress <strong>and</strong> made queen of the plaza. All the elders we interview<br />

assure us that this custom is very old. One woman, 89 year old Doña Ofelia, declares “Anacaona was<br />

revered in this plaza when my gr<strong>and</strong>parents were children <strong>and</strong> their gr<strong>and</strong>parents before them.<br />

<strong>Amantina</strong> informs us that she has cared for<br />

<strong>Anacaona’s</strong> stone for a great part of her life. She<br />

inherited these duties from her husb<strong>and</strong>’s sister.<br />

<strong>Amantina</strong>’s husb<strong>and</strong> had cared for the stone as well for<br />

many years after inheriting these duties from <strong>Amantina</strong>’s<br />

gr<strong>and</strong>mother. At one point the entire family had cared<br />

for the stone. It became abundantly clear to me that this<br />

custom was very old. “Some people say there is nothing<br />

(spiritual) here. Haitians, Evangelicals, people from

other countries <strong>and</strong> religions will say this. But the teaching is that the misterios, those Indian spirits that<br />

dwell here <strong>and</strong> our queen Anacaona only make their presence known to those people that are truly<br />

worthy.” This is the Agua Dulce sect. Within this sect sunrise ceremonies are common. Associated with<br />

the sunrise ceremony is a spirit known as “Gamao or Guamao” who rules over the entire Indian realm. In<br />

this place however Anacaona <strong>and</strong> her husb<strong>and</strong>, Cacique Caonabo reign supreme. This sounds strikingly<br />

similar to ancestor worship.<br />

The misterios (spirits), is a complex spiritual belief system sometimes associated with “la 21<br />

division. “ In turn the 21 Division is sometimes referred to as Dominican voodoo. Although Dominican<br />

voodoo is often compared to its Haitian namesake, they are in fact different. However often times<br />

outsiders will confuse the two. The closer one is to Haiti the stronger the African component within 21<br />

Division becomes. Haitian Voodoo also makes reference to Indians, but not to the extent as do the<br />

Dominican sects.<br />

The Liboristas (Olivoristas) also make reference to Indians in many if not most of their<br />

ceremonies. Some past researchers noted this strong Indian content. But historians have long claimed that<br />

there are no Indians descendants left on the isl<strong>and</strong>. Some investigators suggest that this association to<br />

Indians may in fact have a European “water nymph” origin or perhaps attributed to the Africans that were<br />

brought as slaves to this region. All sects in this region have another thing in common; the usage of caves<br />

for ceremonies. Interestingly these caves were used by the Classic Taino for ceremony as well.<br />

The Maguana region was the melting pot of many<br />

different peoples. Spiritual ideas <strong>and</strong> customs of the native<br />

Taino Indians, Fon <strong>and</strong> Ewe people from the Congo region<br />

of Africa, Canary Isl<strong>and</strong>ers <strong>and</strong> people from Andalusia,<br />

Spain all coalesced here. American Ethnographer Martha<br />

Ellen Davis documented many of these traditions in her film<br />

"Papá Liborio: el santo vivo de Maguana." (3 ) No doubt<br />

these people had many similar customs <strong>and</strong> may have<br />

influenced the native Taino people to an extent. It is a<br />

historical fact that after contact with Europeans, numerous<br />

groups of Indians escaped to the mountains <strong>and</strong> formed<br />

maroon communities across the isl<strong>and</strong>. Others lived on the outskirts of Spanish society preserving many<br />

of their beliefs which undoubtedly blended with that of other ethnic groups.<br />

This scenario makes it difficult to pinpoint exactly what is Taino <strong>and</strong> what is not. Many scholars<br />

claim that as more <strong>and</strong> more Africans <strong>and</strong> Europeans arrived, these maroon colonies gradually mixed out<br />

of existence. Others strongly uphold the total extinction model which posits that an entire race of people<br />

vanished 30 years after contact with the Spaniards. That inexplicably <strong>and</strong> for some strange undefined<br />

reason these extinct peoples were able to influence those that displaced them with so many aspects of<br />

their culture, language <strong>and</strong> customs. Yet, many visitors to the isl<strong>and</strong> are struck with the amount of<br />

indigeneity of the isl<strong>and</strong>. Take for example this seemingly paradoxical statement by Alastair Reed<br />

““Although the Taino population of Hispaniola was “wiped” out within thirty years of the discovery, it is<br />

as though the Tainos had left their mode of life embedded in the l<strong>and</strong>, to be reenacted in a surprisingly<br />

similar form by the campesinos now”. Rich soil, a benign climate, <strong>and</strong> plants of predictable yield<br />

guarantee basic survival, although today on a threadbare level..... Pucho asks me a lot about the Tainos--<br />

I once read him from Las Casas the descriptions of their common crops <strong>and</strong> agricultural practices, <strong>and</strong><br />

he was as startled as I was that everything was all still growing within shouting distance, that we were<br />

more or less enacting the Tainos' agricultural patterns, using their words, living more or less as they did<br />

except for our clothes <strong>and</strong> our discontents. (4)

The debate as to whether the Taino left descendants <strong>and</strong> consequently culture <strong>and</strong> custom, or not,<br />

has been raging for some time now. Often times this debate can be pretty vicious in particular from many<br />

historians who pretty much accept the notion that history is not biased <strong>and</strong> therefore literally true.<br />

Opponents of Taino survival often times dem<strong>and</strong> proof of Indian ancestry <strong>and</strong> curiously down play any<br />

evidence to the contrary offered. These voices suggest that in order for one to be Indian, he or she must be<br />

culturally <strong>and</strong> racially pure. A glance through the pages of “Taino Revival: Critical Perspectives on<br />

Puerto Rican Identity <strong>and</strong> Cultural Politics” a book edited by Gabriel Haslip-Vieras, critically ridicules<br />

Caribbean peoples who identify with their Indigeneity . Within its pages one finds disparaging chapters<br />

with titles such as “The Indians are coming1 The Indians are coming!” <strong>and</strong> “Making Indians out of<br />

Blacks. “ Mostly this book suggest that A) Indio identified people of the Caribbean are denying their<br />

Negritude, B) That these people are identifying with a group that historically did not collectively call<br />

themselves Taino C) that the majority of Caribbean peoples are in fact African <strong>and</strong> finally D) Haslip-<br />

Vieras suggests that the Taino identity movement began during the 1970’s as a direct result of Puerto<br />

Rican grass roots opposition to statehood. (5)<br />

Offering Proof of survival would actually be an anomaly as true science does not offer proof to<br />

support a theory but rather a preponderance of evidence that supports said theory. Modern investigative<br />

tools are gathering evidence of strong undeniable indigeneity, survival <strong>and</strong> continuity via genetics,<br />

linguistics, ethnography etc. On the other h<strong>and</strong> proponents of Taino extinction constantly offer historical<br />

records <strong>and</strong> census counts written by the colonizers themselves as absolute “proof” of total Taino<br />

extinction. Canadian Anthropologist Dr. Max Forte argues that in the “Caribbean” what is not clearly<br />

European is by default considered black; it appears that Indians are held to a “purity” st<strong>and</strong>ard, whereas it<br />

only takes one drop of African blood to make one black.” (6) It is no wonder that ethnographers<br />

investigating Dominican culture leave Taino cultural <strong>and</strong> religious influence in the colonial past <strong>and</strong> focus<br />

only on the African or Spanish.<br />

The assertion that the Taino<br />

did not collectively call themselves<br />

Taino or rather were not a<br />

homogenous group is interesting.<br />

Certainly, archaeology gives us a<br />

window into the pre-Columbian past<br />

<strong>and</strong> indeed the Taino were a mixture<br />

of various ethnic groups who arrived<br />

in the Caribbean over thous<strong>and</strong>s of<br />

years from the Yucatan <strong>and</strong> South<br />

America. Columbus did take note<br />

however that there was a general sameness to their cultures from the Bahamas to Puerto Rico. Juan Bosch<br />

states that one of Fray Pane’s first Indian converts to Christianity claimed that all the isl<strong>and</strong>s were called<br />

Bohio (home). (7) Can we imagine that perhaps groups of people isolated in Caribbean for millennia with<br />

similar material culture may have had a sense of unity, of being a people?<br />

There are some who claim that the term Taino was coined from the Taino word NiTaino <strong>and</strong> was<br />

applied to the indigenous people of the Caribbean by archeologists. However the term first appears in the<br />

writings of Diego Alvarez Chanca a physician <strong>and</strong> companion of Christopher Columbus who claimed that<br />

the Indians approached their boats yelling “Taino- Taino!”

The Africans never collectively called themselves African either. Yet many modern researchers<br />

such as Haslip-Vieras insist that Caribbean peoples today are mostly African. Identifying with Taino,<br />

which is synonymous with all Indigenous Caribbean people, is viewed as suspect <strong>and</strong> inauthentic.<br />

Questions of authenticity are rather disturbing as no one has yet set the st<strong>and</strong>ard as to what is <strong>and</strong> what is<br />

not Taino. What is certain today is that Caribbean people of Indigenous extraction call themselves Taino,<br />

while others refer to all dark skinned people as African.<br />

The people of Maguana have traditionally identified with both Indians <strong>and</strong> Africans. Why are<br />

they so drawn to Native American culture <strong>and</strong> religiosity? Can an entire people be wrong about their<br />

ancestry, their culture <strong>and</strong> customs, their origins? Or are they all collectively lying? In Maguana many<br />

people identify as Afro-Indigenous <strong>and</strong> attribute their religious beliefs to both. But how can we be certain<br />

of this racial <strong>and</strong> ethnic mixture?<br />

Recent genetic DNA sequencing studies can <strong>and</strong> do shed light on this debate. Unlike history<br />

genetics is a complete science. Mitochondrial DNA is passed down from a mother to her children <strong>and</strong><br />

unlike Autosomal DNA which recombines at a fast rate, mtDNA does not recombine easily. Haplogroups<br />

are further divided into Halpo-types which are mutations which take upwards of two thous<strong>and</strong><br />

years to do so. Thus an American Indian from North America who is Haplo- group A can be easily<br />

distinguished from a South American Indian of the same Haplo-group via his Halpo-type. All American<br />

Indians descend from four halpo groups, A, B, C <strong>and</strong> D. These are found throughout the Western<br />

Hemisphere. In the Dominican Republic one study found that Dominicans have 9 Native American<br />

lineages via Haplo-group A alone. Of these 9 lineages 3 are said to have arrived via the slave trade during<br />

the past 500 years. The other six lineages however are local mutations not found outside the Caribbean .<br />

This study found that 33% of Dominicans had mtdna A (7). A similar study by Japanese geneticists<br />

Tajima/Hamaguchi asserts the following “Thus, the maternal gene pool of the Dominican Republic<br />

population may mainly consist of both Native American <strong>and</strong> African ancestries. (8)<br />

African based syncretic religions such as Santeria traditionally utilize the names of<br />

Catholic saints in place of names of their African deities, no doubt used as a survival strategy to<br />

hide them from their oppressors. An obvious difference between Santeria <strong>and</strong> Agua Dulce for<br />

example is that locals revere Indian spirits which use the names of Cacike’s such as Anacaona,<br />

Caonabo, Guarionex etc. Further many of the spirits worshipped such as Anaina, Jibaro, Ercilia<br />

Dasolei etc. appear to be post contact indigenous figures. It gives the impression that the<br />

reverence for ancient Taino chieftains once held in this valley is still strong today. The<br />

syncretism between Central African traditions <strong>and</strong> Taino is indeed strong as both peoples merged<br />

in various degrees during the colonial period <strong>and</strong> created this beautiful blend of culture <strong>and</strong> ideas<br />

Jan Lundius writes, “The San Juan Valley is the entire isl<strong>and</strong>s center for Indian worship; It<br />

appears as if there are several historical reasons behind its elevated status. Hispaniola’s first<br />

chronicler, Bartolome de las Casas, tells that Hispaniola was divided into five Taino<br />

“kingdoms”. Of these Maguana was the biggest, <strong>and</strong> most influential, “a country, very<br />

temperate <strong>and</strong> fertile”. When Columbus arrived, Maguana was governed by Caonabo, the most<br />

powerful Cacike (chieftain) of the entire isl<strong>and</strong>, “who for power, Dignity <strong>and</strong> gravity,<br />

ceremonies which were used towards him, far exceeded the rest.” (9)<br />

The traditions that exist in this region <strong>and</strong> other isolated areas as well are very old. The<br />

debate as to whether or not they are Indian will undoubtedly continue. But within this<br />

community <strong>and</strong> others like it there is no debate. My personal opinion is that the principles of

Occam’s Razor can <strong>and</strong> be applied to this debate. A simple theory suggesting that perhaps Taino<br />

people survived in isolated communities across the isl<strong>and</strong>, preserving scattered versions of their<br />

many spiritual beliefs, food ways, planting ways, linguistics, genes etc makes more sense than<br />

the total extinction model.<br />

Dominican writer <strong>and</strong> philanthropist Manuel <strong>Garcia</strong> Arevalo says "The persistence of a<br />

Taíno genetic component in contemporary Dominican life, along with the survival of certain<br />

undeniably indigenous beliefs <strong>and</strong> traditions (kept alive in rural areas <strong>and</strong> passed along through<br />

oral tradition) requires the recognition of a native substratum in our midst today” (10)<br />

<strong>Amantina</strong>’s church which is visited daily by worshippers is a big, dimly lit room, with pictures of<br />

saints <strong>and</strong> statues of the same. African Palo drums <strong>and</strong> Indian figurines are everywhere. Casabe, water<br />

<strong>and</strong> stones are placed in the altar dedicated to Anacaona. <strong>Amantina</strong> repeatedly reminds us that Anacaona<br />

is an Indian woman of the water. I am reminded of descriptions of Taino female deity, Atabeira by<br />

Spanish chronicler Fray Ramon Pane. A footnote by Ulloa, In the Revised Antiquities of the Indians book<br />

by Pane states “Atabeira (from atte the vocative for “mother” <strong>and</strong> the attached suffix beira “water”) is<br />

the equivalent of mother of the waters.” (11) I cannot help but wonder if perhaps this Anacaona is in<br />

reality the goddess Atabeira. Certainly it is worthy of a deeper study. Opiyelguabiran the so-called dog<br />

deity for example was a deity which legend has it disappeared into a river when the Spanish arrived on<br />

the isl<strong>and</strong>. Oral tradition tells us that this deity still makes his presence known. Although not revered he is<br />

feared. Legends of “Indio del Charco” are attributed to him. “ Still today through 5 centuries this<br />

quadruped cemi governs threads of the imagination of our campesinos. The story has transformed itself of<br />

course. People from the interior swear that an Indian male or female combs its hair with a golden comb---<br />

further…There is a small cave with a wide interior. In it lives a saint with four legs that comes out at<br />

night to bathe…(12)<br />

Every time <strong>Amantina</strong> speaks she rings a bell <strong>and</strong> sprays a sweet smelling mist. I am curious of the<br />

bell <strong>and</strong> ask her why she does this <strong>and</strong> if she has always used a bell. “In the old days people used a<br />

maraca, but later people found that the sound of the bell reaches god faster <strong>and</strong> changed <strong>and</strong> thus was<br />

changed from maraca to bell.” She says.<br />

We reach the stone. I light tobacco <strong>and</strong><br />

offer a prayer of gratitude for finally making it<br />

to this sacred place <strong>and</strong> the reception we have<br />

received. As we all st<strong>and</strong> there, it seems fitting<br />

to gift <strong>Amantina</strong> my headdress. I check first<br />

with my wife of course, who graciously agrees.<br />

A light rain begins to fall. “ From this moment<br />

on I will wear this headdress for every<br />

ceremony that we hold for Anacaona. It is an<br />

honor for me to receive such a beautiful gift!”<br />

she exclaims. As the light rain stops, numerous strange ring patterns at least 20 feet in circumference<br />

begin to appear everywhere. I wonder if perhaps it is some sort of fungi? But <strong>Amantina</strong> softly says<br />

“Anacaona is very happy with you, the rain drops are tears of joy <strong>and</strong> the rings mark the spots where<br />

ancestral bohios (homes) once stood.”<br />

Looking deep into my eyes she says “Jorge, we have a lot of work to do here. You must return <strong>and</strong><br />

help me accomplish this. There are many secrets here. There are herm<strong>and</strong>ades (brotherhoods) who are<br />

keepers of many secrets <strong>and</strong> traditions. We are counting on you to return.” She hugs us all, turns <strong>and</strong><br />

walks away. I wish I could have stayed longer, but I know I will return.

1) Fray Ramon Pane- The Antiquities of the Indians p. 10- New edition with an introductory study, notes <strong>and</strong> appendices by Jose Juan<br />

Arrom, tanslated by Susan G. Griswold-“And the woman Guabonito gave Albeborael Guayahona many guanimes <strong>and</strong> Cibas so that<br />

he would wear them tied to his arms, for in those l<strong>and</strong>s the cibas are made of stones very much like marble, <strong>and</strong> they wear the<br />

guanimes in their ears.” (1)<br />

2) Juan Bosch – Indios- Apuntos Historicos y Leyendas-<br />

3) Martha Ellen Davis- "Papá Liborio: el santo vivo de Maguana-https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5dFTB9ij7ag<br />

4) In “Reflections: Waiting for Columbus" by Alastair Reid in "The New Yorker" (February 24, 1992, pp. 57-75)<br />

http://muweb.millersville.edu/~columbus/data/art/REID-01.ART<br />

5) Taino Revival: Critical Perspectives on Puerto Rican Identity <strong>and</strong> Cultural Politics edited by Gabriel Haslip-Vieras<br />

6) Searching for the Digital Ether- Maximillian Forte- http://www.tainolegacies.com/170582889 also Notes on the Indigenous<br />

Caribbean Resurgence on the Internet. In “Indigenous Resrugence in the Contemporary Caribbean” Edited by Maximillian C. Forte<br />

2006- by default iwhen so black is the default identity when writes “They are trying to evade their blackness Can anyone cite a<br />

representative number of examples to support the assertion? If Indians with "one drop" of African blood are evading their<br />

"blackness" by proclaiming themselves Indian, then what do we say of Africans with "one drop" of Indian blood who proclaim<br />

themselves African?). Indeed, "black" is taken as the "normal", "natural", <strong>and</strong> unquestionable default identity of Caribbean peoples in<br />

such arguments, <strong>and</strong> anyone claiming a distinct history must be motivated by a sinister, separatist agenda. Lurking in the background<br />

are unexamined <strong>and</strong> thus unquestioned attachments to outdated ideas of assimilation <strong>and</strong> evolution, better suited to the era of<br />

scientific racism than the post-colonial period.<br />

7) Genetic Prints of Amerindian female migrations through the Caribbean revealed by control sequences from Dominican Haplo Group<br />

A Mitochondrial DNA By Arlin Feliciano Vélez 2006<br />

8) Genetic background of people in the Dominican Republic with or without obese type 2 diabetes revealed by mitochondrial DNA<br />

polymorphism Tajima/ Hamaguchi<br />

Received: 2 April 2004 / Accepted: 18 June 2004 / Published online: 5 August 2004 The Japan Society of Human Genetics <strong>and</strong><br />

Springer-Verlag 2004 p. 498<br />

9) Jan Lundius- The Great Power of God in the San Juan Valley, Syncretism <strong>and</strong> Messianism in the Dominican Republic. p. 137<br />

10) “Trans-culturation in the contact period <strong>and</strong> contemporary Columbian Consequences”, by <strong>Garcia</strong> Arevalo, 1990 page 275<br />

11) Fray Ramon Pane- The Antiquities of the Indians p.4- New edition with an introductory study, notes <strong>and</strong> appendices by Jose Juan<br />

Arrom, tanslated by Susan G. Griswold<br />

12) Juan Bosch – Indios- Apuntos Historicos y Leyendas p. 41<br />

13) Lynne Guitar Dr. Lynne Guitar in “Cultural Genesis: Relationships among Indians, Africans <strong>and</strong> Spaniards in Rural Hispaniola, first<br />

half of the sixteenth century, page 315, 1998.