Gateway Chronicle 2022

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

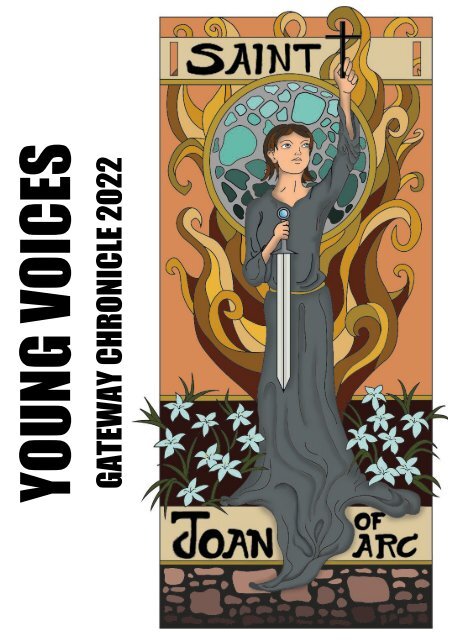

YOUNG VOICES<br />

GATEWAY CHRONICLE <strong>2022</strong>

2 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

CONTENTS<br />

FROM THE EDITORS 5<br />

MEDIEVAL PERIOD<br />

Were medieval children really seen as miniature adults? 7<br />

How far do you agree that Richard II lost his throne due to<br />

his cousin Henry’s ambition? 12<br />

The maid of Orleans 17<br />

Arthur Tudor’s untimely death in childhood 20<br />

EARLY MODERN PERIOD<br />

‘The prettiest and dearest child’ – what does the death of John Evelyn’s son<br />

in 1658 tell us about childhood in 17 th century England? 24<br />

Phillis Wheatley 27<br />

The forced assimilation of Native American children 30<br />

How significant was the 1870 education act? 33<br />

MODERN PERIOD<br />

Dismantling the rabbit-proof fence 38<br />

Youth and the Easter Rising 41<br />

Childhood in the early Soviet Union 43<br />

The impact of the Nazi regime on the youth of Germany 46<br />

A tale of two viruses 50<br />

‘Masters of the new society’: how childhood was redefined in 20 th century China 52<br />

A pioneer of American education: the story of Ruby Bridges 57<br />

Victims and protagonists: children and the troubles 59<br />

The historical significance of Lego 63<br />

The history of childhood 65<br />

3 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

4 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

FROM THE<br />

EDITORS<br />

Jonathan B<br />

Ben H<br />

Hannah P<br />

Arthur R<br />

This year, after the huge changes that<br />

have affected children’s lives and<br />

education around the world, we thought it<br />

fitting to give a voice to some incredible<br />

young people who have achieved so much<br />

despite their youth. What makes this<br />

edition so interesting is the plethora of<br />

ways that pupils and teachers throughout<br />

the School have interpreted ‘Young<br />

Voices’.<br />

It is also appropriate that considering<br />

recent humanitarian crises perhaps, the<br />

<strong>Chronicle</strong> examines the suffering of young<br />

people, as well as celebrates the rise in<br />

youth popular protest and young leaders.<br />

With such a broad range of articles, from<br />

youth movements to child rulers and Lego,<br />

there truly is something to whet everyone’s<br />

historical appetite.<br />

We would like to extend our thanks to all<br />

the teachers and pupils who contributed to<br />

our <strong>Chronicle</strong> and enriched us with their<br />

knowledge of children throughout history.<br />

We are indebted to Mrs Gregory for her<br />

tireless work in rallying us, keeping up<br />

morale and proofreading the whole<br />

<strong>Chronicle</strong>, and to Oli, whose fantastic<br />

cover hides our lack of artistic prowess.<br />

We hope you find these articles thoughtprovoking<br />

and, ultimately, engaging as well<br />

as serving as a reminder that no voice is<br />

ever too small to be heard.<br />

5 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

6 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

MEDIEVAL PERIOD<br />

7 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

WERE<br />

MEDIEVAL<br />

CHILDREN<br />

REALLY SEEN<br />

AS MINIATURE<br />

ADULTS?<br />

Ben H, U6VLS<br />

In Centuries of Childhood (1962), Philippe<br />

Ariѐs asserts that ‘in medieval society the<br />

idea of childhood did not exist’, arguing that<br />

children were seen as ‘miniature adults’, on<br />

the basis that children tended to be<br />

depicted in adult dress by artists. 1 The<br />

view that childhood did not exist in the<br />

medieval period has since become<br />

ingrained into the popular imagination, yet<br />

this is perhaps a misconception. Ariѐs<br />

argues that during the medieval period,<br />

people were not aware of their exact age,<br />

there didn’t exist a culture of childhood and<br />

education was limited; essentially,<br />

childhood was not distinct from adulthood.<br />

The first statement is of little significance,<br />

as people would have been roughly aware<br />

of their age and when their birthday was.<br />

Moreover, the evidence suggests that there<br />

did exist a culture of childhood and, whilst<br />

education was limited, this was a result of<br />

the social hierarchy and not because<br />

children were not seen as intellectually<br />

indistinct from adults. Another commonly<br />

held view is that children were not loved by<br />

their parents due to high rates of infant<br />

mortality, but the evidence suggests<br />

otherwise. The medieval period can be<br />

defined as lasting from the fifth to midsixteenth<br />

centuries, but due to the<br />

availability of evidence, this examination of<br />

childhood will focus on the twelfth century<br />

onwards. The balance of evidence from<br />

this period indicates that childhood was<br />

recognised as distinct from adulthood and<br />

that children were not seen as miniature<br />

adults.<br />

There is little to suggest that there did not<br />

exist a unique childhood culture, as toys<br />

from the period have been recovered. The<br />

Museum of London displays a toy knight,<br />

dating from c.1300, which is described as<br />

1<br />

Anastasis Ulanowicz, ‘Philippe Ariѐs’,<br />

https://www.representingchildhood.pitt.edu/pdf/<br />

aries.pdf [accessed 21/11/21], p. 2<br />

8 | <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong>

‘one of the earliest examples of a massproduced<br />

medieval metal toy.’ 2 Another toy<br />

knight, dating back to the thirteenth<br />

century, can be found on display at the<br />

Walters Art Museum. The existence of<br />

mass-produced toys indicates that it was<br />

common for children to play, which detracts<br />

from the argument that children were seen<br />

as miniature adults. A mechanical bird from<br />

the late medieval period, ‘capable of<br />

pivoting on a frame so that the tongue<br />

moved in and out’, has also been<br />

recovered, as have toy utensils. 3 Similarly,<br />

children played games and doodled, with<br />

‘Handy-dandy’ being referenced by the<br />

poet Langland in the 1360s, and the<br />

childhood drawings of Onfim Wuz, dating<br />

back to the twelfth or thirteenth century,<br />

having been recovered in Novgorod. 4, 5<br />

Moreover, the crown levied a tax on<br />

imported ‘puppets or babies for children’ in<br />

1582, reflecting the money generated by<br />

the toy industry. 6 In addition, the account<br />

of Bartholomeus Anglicus, translated into<br />

English by John Trevisa in 1398, indicates<br />

that children preferred the company of<br />

those their own age:<br />

they love talkynges and counsailles of<br />

suche children as they bene, and forsaken<br />

and voyden companye of olde men 7<br />

As such, there is a wealth of evidence<br />

suggesting that a distinct childhood culture<br />

existed, even paralleling the experiences of<br />

children today. Children had toys, played<br />

games, drew, and preferred the company<br />

of those their own age. In fairness,<br />

contemporary artwork depicting this is<br />

limited, but this in itself shows the limit of<br />

using art as the basis of a conclusion about<br />

childhood. Paintings of children dressed in<br />

adult clothes do not represent the<br />

childhood culture that existed in the<br />

medieval period. Rather, evidence of toys,<br />

doodles and games demonstrate the<br />

existence of a distinct childhood culture.<br />

Ariés’ conclusions about education are<br />

similarly unsubstantiated. Whilst education<br />

was limited to the upper classes, the fact<br />

that children were seen as intellectually<br />

distinct from adults indicates a recognition<br />

of childhood. It is to be expected that<br />

educational opportunities were limited, as<br />

working-class children continued to be<br />

employed late into the nineteenth century,<br />

with the framework for the schooling of all<br />

children between the ages of five and<br />

twelve only being set out in 1870. As such,<br />

it would be unfair to claim childhood did not<br />

exist in medieval times on the basis that<br />

few children attended school. Despite the<br />

2<br />

Museum of London, ‘Miniature knight on<br />

horseback’,<br />

https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/onlin<br />

e/object/145021.html [accessed 21/11/21]<br />

3<br />

Nicholas Orme, ‘The Culture of Children in<br />

Medieval England’, Past & Present, No. 148<br />

(Oxford University Press, 1995) pp. 57-59<br />

4<br />

The Vision of William concerning Piers the<br />

Plowman, ed. W. W. Skeat (Oxford, 1886), p.<br />

106<br />

5<br />

Paul Wickenden, ‘The Art of Onfim: Medieval<br />

Novgorod Through the Eyes of a Child’,<br />

http://www.goldschp.net/SIG/onfim/onfim.html<br />

[accessed 21/11/21]<br />

6<br />

Hugh Cunningham, ‘Histories of Childhood’,<br />

The American Historical Review, Vol. 103, No.<br />

4 (Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 1200<br />

7<br />

Nicholas Orme, ‘The Culture of Children in<br />

Medieval England’, Past & Present, No. 148<br />

(Oxford University Press, 1995) p. 48<br />

9 | <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong>

majority of children being in work, the<br />

evidence suggests that children were seen<br />

as intellectually distinct from adults.<br />

Schoolbooks are indicative of this, with<br />

several dozen, dating back to the fifteenth<br />

and early sixteenth centuries, having<br />

survived. Orme comments that ‘Masters<br />

composed [Latin] exercises […] with<br />

reference to the kinds of things that would<br />

interest their pupils and keep them<br />

attached to their work’, such as topics<br />

‘related to the schoolroom, the pupils and<br />

the everyday world’. 8 In these Latin<br />

translations, there are references to games<br />

such as ‘cherry-stones’ and ‘sayings,<br />

riddles and poems or songs current among<br />

the young’, providing further evidence that<br />

there existed a distinct childhood culture. 9<br />

Whilst schooling was also limited based on<br />

gender, girls born into the nobility were<br />

trained to perform domestic roles, which<br />

still reflects their being seen as<br />

intellectually distinct from women.<br />

However, students attended the<br />

universities of Oxford and Cambridge from<br />

as young as thirteen, suggesting that<br />

people were seen as children for a shorter<br />

period of time than we would expect today.<br />

This is a common theme throughout the<br />

period, however, with people getting<br />

married and having children in their midteens,<br />

and average life expectancy being<br />

47-48 during the fifteenth and sixteenth<br />

centuries. Yet despite the end of childhood<br />

potentially occurring at a younger age, and<br />

the majority of children being in work,<br />

children were seen as intellectually distinct<br />

from adults during the period, indicating<br />

that the concept of childhood existed.<br />

8<br />

Nicholas Orme, ‘The Culture of Children in<br />

Medieval England’, Past & Present, No. 148<br />

(Oxford University Press, 1995) p. 76<br />

9<br />

Ibid.<br />

10<br />

‘Plague, famine and sudden death: 10<br />

dangers of the medieval period’,<br />

10 | <strong>Gateway</strong> <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

Another popular view is that due to high<br />

infant mortality rates, parents did not love<br />

their children, using them only as tools to<br />

either help with work or to advance their<br />

family’s interests. It is true that the death<br />

rate among medieval children was high by<br />

modern standards, with estimates that 20-<br />

30% of children died before the age of<br />

seven. 10 Moreover, parents could later lose<br />

their children to disease, battle, or<br />

childbirth. Yet applying modern perspective<br />

to the past achieves little. Whilst infant<br />

mortality was an ordinary part of life, it is a<br />

misconception that medieval parents<br />

closed themselves off from their children,<br />

as the biography of William Marshal, born<br />

in 1147, suggests. The consensus among<br />

scholars is that the biography was written<br />

by someone who knew William personally,<br />

and it depicts William as having had a<br />

loving relationship with his mother Sybil. 11<br />

According to the biography, every time<br />

William left home Sybil wept, which the<br />

biographer describes as ‘only natural’. 12<br />

https://www.historyextra.com/period/medieval/w<br />

hy-did-people-die-danger-medieval-period-lifeexpectancy/<br />

11<br />

Rebecca Slitt, ‘Medieval Childhood in<br />

England: The Case of William Marshal<br />

12<br />

Ibid.

The fact that the biographer saw this as<br />

‘natural’ indicates that medieval children<br />

had loving relationships with their parents.<br />

However, this is an account of a noble<br />

child, which may not reflect the nature of all<br />

relationships between children and their<br />

parents. In particular, a noble child would<br />

have been less likely to die an infant.<br />

Nonetheless, it does dispel arguments that<br />

parents distanced themselves from their<br />

children, using them solely as political tools<br />

or in the service of their family, rather than<br />

caring for them. Moreover, John Evelyn’s<br />

diary account of his child’s death from 1658<br />

directly addresses the argument about high<br />

rates of infant mortality. Whilst it is about a<br />

century out from what can be considered<br />

‘medieval’, it nonetheless demonstrates<br />

that parents loved their children despite<br />

high rates of infant mortality. Evelyn<br />

describes his child as ‘deare’ and his<br />

‘griefe & affliction’ as ‘unexpressable’,<br />

having lost a son aged five. 13 He shows<br />

other signs of grief in his blame of others,<br />

accusing the ‘woman & maide that tended<br />

[his child]’ of suffocating him by covering<br />

him ‘too hott with blankets […] neere an<br />

excessive hot fire’. 14 Evelyn even states<br />

‘Here ends the joy of my life’, reflecting the<br />

significance of children to their parents. 15<br />

As such, it is likely that despite the risk of<br />

infant mortality, parents loved their<br />

children. Both the biography of William<br />

Marshal and John Evelyn’s diary account<br />

support this idea.<br />

In conclusion, children were not seen as<br />

miniature adults in the medieval period.<br />

The balance of evidence suggests that<br />

childhood was recognised as a separate<br />

phase of development. Children were<br />

viewed as intellectually distinct from adults,<br />

and there is clear evidence that there<br />

existed a culture of childhood. It also<br />

seems highly likely that parents loved their<br />

children, despite the popular view that, due<br />

to high rates of infant mortality, this was not<br />

the case.<br />

13<br />

John Evelyn’s diary, January 1658<br />

14<br />

Ibid.<br />

15<br />

Ibid.<br />

11 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

HOW FAR DO YOU<br />

AGREE THAT<br />

RICHARD II LOST<br />

HIS THRONE DUE<br />

TO HIS COUSIN<br />

HENRY’S<br />

AMBITION?<br />

Every year students in the Sixth Form<br />

about to study Medieval History research a<br />

key topic for an Essay Competition. This<br />

year’s winner was Milly CH, who<br />

considered the reasons why Richard II was<br />

deposed in 1399. Richard had become<br />

King at the age of just ten and negotiated<br />

successfully with the rebels in 1381 at the<br />

age of fourteen. Yet his reign was marred<br />

by rivalry with his cousin who was a similar<br />

age and their teenage conflict resulted in<br />

deposition and death…<br />

12 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

Bolingbroke’s ambition, both driven by his<br />

personal goals and Richard’s treatment of<br />

him, were a key factor in Richard’s<br />

deposition but it would be inaccurate to call<br />

it the most important factor. Instead,<br />

Richard’s own arbitrary actions led to a<br />

tyrannical reign and his losing his throne,<br />

although the declining authority and<br />

prestige of the crown is another factor to<br />

consider.<br />

Bolingbroke’s ambition, aptly captured in<br />

Shakespeare’s presentation of him in<br />

‘Richard II’, was a crucial factor in<br />

determining the fate of the throne in 1399.<br />

This ambition can perhaps be most clearly<br />

seen in the formation of his alliance with<br />

the Percy family in the North, a family<br />

continually slighted by Richard in his<br />

‘persistent efforts to break the independent<br />

power of the Percies’. As an incredibly<br />

powerful political and military force, this<br />

alliance was invaluable in the actuality of<br />

removing Richard II from the throne, the<br />

combined strength of Bolingbroke’s<br />

Lancastrians and the Percies proving<br />

undefeatable to the absent king.<br />

Bolingbroke’s ambition is thus evident as<br />

his political prowess aided his ambition to<br />

make a bid for the throne. By capitalising<br />

off the harm Richard himself had caused in<br />

the earlier days of his tyranny, Bolingbroke<br />

not only furthered his own goals but also<br />

united a fearful English nation behind, what<br />

initially appeared to be, a strong candidate<br />

for the throne. However, despite<br />

Bolingbroke’s ambition, it is key to note ‘the<br />

Percies opposed Henry’s design on the<br />

throne up to the very last.’ The<br />

weaknesses of Bolingbroke’s ambition are<br />

thus able to be seen as even his strongest<br />

allies could not be said to be fully<br />

committed to his desire for the crown.<br />

Continuing in this manner, Bolingbroke had<br />

proved himself to be capable of betraying<br />

others in order to get what he wanted,<br />

highlighting the ambition present within him<br />

which eventually allowed him to seize the<br />

throne of England. During the Lord’s<br />

Appellants’ uprising of 1388, Bolingbroke<br />

had brought the great masses of<br />

Lancastrian soldiers who weren’t abroad<br />

with his father to help stop the royal retinue<br />

in December 1387. Here, not only the<br />

beginnings Bolingbroke’s desire for a<br />

different monarch on the throne evident but<br />

also how his drive enabled his goal to be<br />

achieved. Although it was only temporary,<br />

the events of 1388 definitively set the<br />

scene for Bolingbroke’s own successful bid<br />

for the crown eleven years later,<br />

underlining the extent of his ambition and<br />

how it was crucial in later events.<br />

Furthermore, despite the possibility of it<br />

being fiction (although this has somewhat<br />

been dismissed thanks to Professor Given-<br />

Wilson), Bolingbroke sold out Mowbray to<br />

the king, claiming of treasonous<br />

advantages. It is thus key to note although<br />

Henry Lancaster clearly disapproved of<br />

Richard on the throne, as evidenced by his<br />

actions in 1388, he was not above going<br />

against these beliefs for his own personal<br />

gain – in this case, to obtain the trust of the<br />

king. Hence, even when his ambition was<br />

not being shown in actions and events<br />

directly relating to Richard II’s deposition in<br />

1399, Bolingbroke’s desire to achieve his<br />

goals can be seen to greatly influence the<br />

political climate of the Middle Ages, setting<br />

precedent for later years. However, it<br />

would not be fully accurate to say<br />

Bolingbroke’s ambition was the main<br />

reason for deposing Richard II as he<br />

publicly stated he was simply arriving back<br />

from exile to get his inheritance. There is<br />

no evidence until Henry was sure he would<br />

win a bid for the crown that he was<br />

attempting to do so, undermining the<br />

overall argument. Without a display of<br />

13 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

ambition for the crown, it would be<br />

inappropriate for a historian to deem this<br />

ambition the primary reason for Richard II<br />

losing his throne as it appears Bolingbroke<br />

was hiding behind the guise of his<br />

inheritance, out of disinterest for the crown<br />

and possibly fear until a successful<br />

outcome was guaranteed. Hence, ambition<br />

could be said to be a key factor but not the<br />

most important one.<br />

Yet, further evidence of Bolingbroke’s<br />

ambition is aided by the many slights<br />

Richard had delivered to his person and<br />

family, without them it would not have been<br />

fuelled in the way it was. Hence, a historian<br />

is able to see Richard’s treatment of his<br />

cousin powered the ambition which helped<br />

in throwing him off the throne. Following<br />

the quarrel between Bolingbroke and<br />

Mowbray, Henry was exiled to France in<br />

1398 which, after the death of his father,<br />

allowing Richard to take over the<br />

Lancastrian estates and bar Bolingbroke<br />

from his inheritance. Not only did this<br />

greatly insult Bolingbroke but also the<br />

Lancastrians as a family, by confiscating<br />

their lands Richard took away their source<br />

of income and pride. This proved to have<br />

deadly ramifications for<br />

Richard, Henry seized the opportunity to<br />

return from exile in order to claim his<br />

inheritance, as he repeatedly stated upon<br />

arrival in Ravenspur in Yorkshire. This<br />

quickly transpired into a bid for the crown<br />

as previous strong supporters of the king<br />

abandoned their positions in order to<br />

support the usurper – largely down to<br />

Bolingbroke’s personality and belief in<br />

chivalry, ambitious to bring it back to<br />

Richard’s England. As Saul notes,<br />

‘Bolingbroke envisaged a personal and<br />

moral solution to the essentially political<br />

problem of his cousin’s misrule’,<br />

underlining the extent of Bolingbroke’s<br />

goals firing his desire for the crown. The<br />

most prominent slight against Henry is<br />

undoubtedly the most famous as well;<br />

Richard went too far, fuelling Bolingbroke’s<br />

ambition to the point of no return. On the<br />

other hand, despite this treatment which<br />

certainly led to the rise of Bolingbroke’s<br />

resentment, thus ambition, the remaining<br />

evidence present does not support this<br />

argument. Without the presence of an<br />

autocratic leader, as Richard was on his<br />

second visitation to Ireland at the time of<br />

Bolingbroke’s arrival back in England, it<br />

was only natural Bolingbroke gained<br />

supporters – they rallied around the most<br />

prevalent autocratic figure in their midst.<br />

Furthermore, it is only recorded Henry<br />

started to champion his right for the throne<br />

after receiving a rapid increase in popular<br />

support; it is also crucial to note no large<br />

group of Richard’s allies deserted him for<br />

his cousin which weakens the argument<br />

significantly in its own right. Hence, while it<br />

is undeniable Richard’s treatment of<br />

14 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

Bolingbroke fuelled his ambition which was<br />

a contributing factor to why Richard II lost<br />

his crown, it would be inaccurate for a<br />

historian to deem his ambition the primary<br />

reason for Bolingbroke’s success seeing<br />

there is so little record of his desire until<br />

later on in events happening.<br />

On the other hand, when considering the<br />

consequences of Richard’s own actions, it<br />

is evident they were the main reason for<br />

the loss of his throne. Arguably a key<br />

reason why Bolingbroke was able to gain<br />

supporters in so little time was due to<br />

Richard’s apathetic stance towards the<br />

common man. Unlike other monarchs<br />

before him, Richard did not try to woo the<br />

average man in his kingdom; this<br />

combined with his tyrannical rule towards<br />

the end of his reign enabled Bolingbroke’s<br />

rapid growth of support. Richard’s tyranny<br />

can be evidenced by his dealing with the<br />

Lords Appellant, with Arundel executed,<br />

Warwick exiled to the Isle of Man and<br />

Gloucester murdered, as well as the<br />

arguably less serious but more impactful<br />

tax issues: his promise of lightening them<br />

from 1389 was never delivered upon, in<br />

1393 a Common’s faith was used to justify<br />

a tax raise and in 1398 a grant of wool and<br />

leather customs for life was given to<br />

Richard. This autocratic rule was just one<br />

of many of Richard’s actions with<br />

unintended consequences, and, in this<br />

case, it was to drive not only the common<br />

man but also the powerful families into<br />

Bolingbroke’s arms. Thus, it can be seen a<br />

large degree of Bolingbroke’s success of<br />

his ambition was drawn from Richard’s<br />

own actions which would suggest them<br />

being the primary reason why the throne<br />

was lost. Furthermore, the king’s tendency<br />

to prefer his favourites over the impartiality<br />

a monarch is meant to show, due partially<br />

to the youth at which he ascended to the<br />

throne. The appeal of the Lords Appellant<br />

from February 1388 aptly shows this, with<br />

it stating ‘false traitors to and enemies of<br />

the king and kingdom, perceiving the<br />

tender age of our said lord the king and the<br />

innocence of his royal person, so caused<br />

him to believe many falsities devised and<br />

plotted by them against loyalty and good<br />

faith, that they caused him to devote his<br />

affection, firm faith, and credence entirely<br />

to them, and to hate his loyal lords and<br />

lieges, by whom he ought rather to have<br />

been governed.’ Although the reliability of<br />

this source is severely hindered by the<br />

political motivations of the Lords, who<br />

sought to rebel against the king, utilising<br />

this appeal to legitimise their motivations to<br />

Parliament, they do bring to light the issue<br />

that Richard was young and easily led<br />

astray in the early years of his reign. Thus,<br />

as a result of the youthful counsel Richard<br />

employed, a precedent for his tyranny was<br />

set in the formative years of his reign which<br />

led to his subjects turning against him,<br />

towards Bolingbroke. Moreover, if one<br />

considers Richard’s treatment of<br />

Bolingbroke an extension of his actions,<br />

that too fuels the idea these actions led to<br />

the loss of the crown. Hence, it is clear to a<br />

historian it was Richard’s own actions were<br />

the primary reason for his deposition rather<br />

than the ambition of Bolingbroke.<br />

Finally, the declining authority and prestige<br />

of the crown made some impact on the<br />

deposition of Richard II. This decline is<br />

evidenced not only by the Lords<br />

Appellant’s challenge but also by Richard’s<br />

own efforts to increase the standing of the<br />

crown. Through imagery, such as the<br />

general pardon issued in 1398, as well as<br />

more practical means, such as claiming the<br />

estates of Gloucester, Arundel and<br />

Warwick in 1397, Richard displayed a keen<br />

interest in bolstering the image of the<br />

15 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

crown to the masses – an interest which<br />

could be interpreted as understanding the<br />

current weakness of its authority. This<br />

weakness can also be seen to manifest<br />

itself in the various unrests during<br />

Richard’s rule: namely the Lords Appellant<br />

Strike as well as the Peasant’s Revolt in<br />

1381. Despite the success of handling the<br />

Revolt, this was arguably the peak of<br />

Richard’s rule, with nothing else quite<br />

comparing to the authoritative stance he<br />

took when dealing with Tyler, yet it still<br />

underlines the continuing dissatisfaction<br />

with the ruling elite and the ability to<br />

express this against the authority of the<br />

crown. Thomas Walsingham notes the<br />

rebels ‘set out for the residence of the duke<br />

of Lancaster. They tore golden cloths and<br />

silk hangings…’ This tells of the lack of<br />

authority both nobles and the crown held<br />

during Richard’s reign, to be disobeyed<br />

and destroyed in such a manner highlights<br />

the beginning of the end of Richard’s rule.<br />

While similar events were mirrored across<br />

Europe, indicating how this factor alone<br />

would not be enough to dethrone the king,<br />

it is key to note the declining authority and<br />

prestige of the crown severely undermined<br />

Richard’s reign, thus bolstering<br />

Bolingbroke’s take of the crown and aiding<br />

in Richard’s deposition.<br />

Overall, while Bolingbroke’s ambition was<br />

certainly a key factor in Richard’s<br />

deposition, the primary cause was certainly<br />

Richard’s actions and the effect they had<br />

on the nation, yet it is also important to<br />

consider the already declining prestige and<br />

authority of the crown.<br />

16 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

THE MAID OF<br />

ORLEANS<br />

Zaid J, 2.4<br />

Joan of Arc is undeniably one of the most<br />

prolific heroines in our history. A young<br />

woman who used her faith and love for her<br />

country to overcome stereotypes based on<br />

her gender, age and social standing and<br />

ultimately becoming one of France's most<br />

renowned heroes. In her short 19 years,<br />

Joan managed to support and lead men<br />

into victories that ultimately helped to win<br />

'The Hundred Year War'. How did a female<br />

child of no social standing, manage to rise<br />

through the ranks and become one of most<br />

famous and idolized women in history?<br />

This article will look at the impact she<br />

played on the freedom of France, and how<br />

she met her untimely and tragic end.<br />

Jeanne D'Arc was born in approximately<br />

1412, to a humble peasant family in the<br />

Northeast Kingdom of France where she<br />

spent the early years of her childhood<br />

helping out on her family farm. A few years<br />

after her birth, the ongoing war began to<br />

move in towards her home and life soon<br />

became more and more challenging for her<br />

small and rural village. Around the age of<br />

12, Joan claimed to be receiving vivid<br />

visions from the Archangel Michael and St<br />

Catherine, instructing her to free France<br />

from England's control. Over the course of<br />

the next few years, her visions increased<br />

she began requesting an audience with the<br />

French Dauphin (the French heir to the<br />

throne). Believing it was her Divine<br />

mission, Joan wanted to take the oldest<br />

son of the King - Charles VII, and lead him<br />

in battle to defend themselves against the<br />

English occupation. After many several<br />

failed attempts, support for Joan finally<br />

started to grow after some predictions from<br />

her visions seemed to miraculously come<br />

true. To disguise herself and in order to<br />

travel safely, Joan was advised by soldiers<br />

17 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

to cut her hair and wear their clothes.<br />

It took some convincing, but eventually<br />

Joan was granted an audience. Using<br />

information from her 'visions' she was able<br />

to convince the Dauphin that she could be<br />

of use. He and his advisors found her to be<br />

strange but charismatic and believed that<br />

there was something about her that could<br />

inspire and encourage the troops. She was<br />

sent to the city of Orleans, where she rode<br />

alongside French forces. Throughout the<br />

span of the battle, Joan was seen<br />

supporting her troops on horseback and<br />

pushing forward her own battle strategies<br />

to push the English back and reclaim the<br />

city. Towards the end of the fighting, she<br />

was injured when an arrow stuck her<br />

shoulder, but she returned quickly to<br />

encourage the soldiers to make one final<br />

push. The following day the English<br />

retreated from the city, and Joan was<br />

recognised for her role in the victory,<br />

earning her the title 'The Maid of Orleans".<br />

From then on, Joan was seen as a symbol<br />

among the French rebellion and rose<br />

through the army ranks. Thanks to the<br />

victory at Orleans and a new succession of<br />

victories, the French Dauphin was finally in<br />

the position to be crowned King of France.<br />

Joan went on to inspire and lead troops<br />

into other battles, and finally the war<br />

started to make a positive turn in France's<br />

favour.<br />

On the 30th of May, while trying to push<br />

back an English advance in Compiegne,<br />

Joan was thrown from her horse and<br />

captured by English allies who placed<br />

under arrest. At her trial, she was<br />

convicted of nearly seventy different<br />

crimes, including witchcraft. The biggest<br />

crime bought against her however, was<br />

deemed to be dressing in men's clothes.<br />

The very thing that Joan had done to keep<br />

herself safe, helped lead to her demise.<br />

She was also labelled as being a heretic, a<br />

crime against religion, for being so vocal<br />

and insistent on the visions she was<br />

receiving from God. She was found guilty<br />

by a biased judge who was a known<br />

English sympathiser and was sentenced to<br />

execution by burning. On the 30th of May<br />

1431. at the young and tender age of just<br />

19, Joan was burned alive at the stake in<br />

front of a crowd of spectators. Before she<br />

died, it is said she cried out 'Jesus!' and<br />

looked for a crucifix that was being held up<br />

in the crowd. Legend says it took three<br />

18 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

attempts to burn Joan before she<br />

eventually turned to ash, shrouding her in<br />

even more supernatural superstition.<br />

Just over 20 years after her death, the<br />

Pope ordered an investigation into Joan's<br />

case. It was deemed that all charges were<br />

false and she was pronounced innocent. It<br />

makes us question why was it that Joan<br />

was falsely convicted of so many crimes?<br />

Historians believe that it probably had<br />

something to do with the impact that Joan's<br />

presence seemed to have on troops in<br />

battle. She was seen as a figurehead, a<br />

symbol of freedom and justice that the<br />

French troops had used to spur them on.<br />

By removing Joan from the picture, the<br />

English hoped that they could damage and<br />

impede the French army's moral. It is also<br />

important to note that Joan of Arc was a<br />

woman. Everything she had achieved up<br />

until this point was completely out of<br />

character, and it was unnerving to them<br />

that a meagre woman of such a young age<br />

was able to hold such standing and do<br />

such damage to their campaign. It might be<br />

fair to say that the English were even afraid<br />

of Joan, and in retaliation labelled her a<br />

witch and a heretic for not abiding to social<br />

stereotypes and for seemingly turning the<br />

war in the French favour. These allegations<br />

would have also encouraged others to<br />

disassociate themselves with Joan, and<br />

serve as a warning to others who wanted<br />

to follow in her footsteps.<br />

remains a role model today, especially for<br />

young women. Until that point, there had<br />

perhaps only been a small handful of<br />

notable women who had been able to<br />

overcome such adversity and push through<br />

the social norms. She had a deep<br />

unfaltering loyalty to her country, and an<br />

unfailing commitment to her belief in God.<br />

Joan of Arc has always been portrayed as<br />

being brave, clever and strong and<br />

although we could never know for sure<br />

exactly what she was like, we can be<br />

certain that she was a woman of great<br />

persistence who was not afraid of doing<br />

what she thought was right. Even at the<br />

end Joan was not scared of her fate, a<br />

tragic demise to an unforgettable young girl<br />

who stared adversity in the face and<br />

overcame it, paving the way for young<br />

women of the future.<br />

Overall, without Joan there to play her key<br />

part in the battles towards the end of The<br />

Hundred Year War, we can only speculate<br />

what the outcomes might have been. Was<br />

it luck? Was it a coincidence? Did Joan<br />

really have a presence about her that could<br />

unite and inspire whole armies? Joan<br />

19 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

ARTHUR TUDOR’S<br />

UNTIMELY DEATH IN<br />

CHILDHOOD<br />

Joseph S, U6IMS<br />

On 2 nd April 1502, the fifteen-year-old<br />

Prince of Wales and heir to the Tudor<br />

throne succumbed to a mysterious illness.<br />

He left behind a young wife, an unprepared<br />

younger brother, and a mourning father.<br />

But what was Prince Arthur’s life like, and<br />

what impact did his childhood have upon<br />

the reign of younger sibling Henry VIII and<br />

beyond?<br />

Heritage<br />

The Tudor dynasty had begun following<br />

Henry Tudor’s victory at the Battle of<br />

Bosworth in 1485; the culmination of the<br />

decades long ‘War of the Roses’. The red<br />

rose of the Lancastrian house had<br />

defeated the white rose of York in what<br />

was a defining moment in British history,<br />

but newly-crowned Henry VII was astute<br />

enough to realise his victory needed to be<br />

bolstered, so there could be no dispute as<br />

to the rightful owner of the English crown.<br />

Thus, he married Elizabeth of York,<br />

unifying the two houses in one family. It<br />

was out of this marriage that Prince Arthur,<br />

Prince Henry and his four other children<br />

were born.<br />

Childhood<br />

As the eldest son, Arthur was the heir to<br />

Henry VII’s crown, meaning he was trained<br />

for kingship from birth. Great hope was<br />

placed on his shoulders, as a young and<br />

healthy symbol of a new golden age<br />

following decades of conflict. Arthur was<br />

given the title of Prince of Cornwall<br />

following his birth but took on the title of<br />

Prince of Wales three years later. As a<br />

teenager he was active in this role but had<br />

little to do due to Wales’ docile nature at<br />

the time. Another key event in his<br />

childhood was his marriage. Catherine of<br />

Aragon was the younger daughter of the<br />

Spanish monarch, who was chosen to wed<br />

Arthur when he was just three years old.<br />

The couple first met in 1501 once Arthur<br />

had reached fifteen, the age of consent at<br />

the time. Although they had a public<br />

bedding, Catherine maintained that the<br />

marriage was never consummated. Both<br />

Arthur and Catherine became ill in 1502<br />

and Arthur never recovered, dying to much<br />

sorrow in April of that year.<br />

Impact on marriage and religion<br />

Arthur’s brief marriage to Catherine of<br />

Aragon was one of great significance.<br />

Catherine later became Henry VIII’s first<br />

wife but was famously unable to provide<br />

him with a living son. And with Catherine<br />

now in the way of marriage with Anne<br />

Boleyn, Henry sought a way out. Having<br />

been a strong Catholic throughout his life,<br />

20 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

he turned to the Pope for a way out. His<br />

protestations centered around his belief<br />

that his marriage was against the Christian<br />

faith, citing the book of Leviticus 20:21,<br />

“’If a man marries his brother’s wife, it is an<br />

act of impurity; he has dishonoured his<br />

brother. They will be childless”.<br />

Catherine consistently claimed her<br />

marriage to Arthur had never been<br />

consummated though and was a strong<br />

Catholic. This ultimately led to Henry’s<br />

dismissal of his Catholic faith and the<br />

emergence of the Church of England,<br />

following Martin Luther’s lead of Protestant<br />

principles seventeen years prior. Had<br />

Arthur’s short marriage never have<br />

happened, Henry would never have had to<br />

abandon his faith that had stayed with him<br />

through childhood. Moreover,<br />

Protestantism may never have gained the<br />

traction it sees today, as the majority of<br />

Protestant countries are member of the<br />

British Commonwealth, and the religion’s<br />

spread is clearly due to Britain’s<br />

colonisation following Henry VIII’s<br />

decisions. Henry’s divorce set a precedent<br />

that is increasingly followed to this day.<br />

Impact on Henry VIII<br />

Henry and Arthur did not see much of each<br />

other during their childhood, because<br />

Arthur was often taken to train in the art of<br />

being a great king, educated by famous<br />

noblemen in the art of battle and by<br />

academics to study Latin, science, and<br />

other disciplines. However, his untimely<br />

death did spring Henry into a surprise role<br />

for which he was largely unprepared, as he<br />

spent the majority of his childhood with his<br />

grandmother, Margaret Beaufort, with<br />

whom he had an excellent relationship.<br />

Had Arthur lived into adulthood Henry<br />

would have never risen to the throne,<br />

depriving Britain of one of its foremost<br />

historical figures.<br />

Impact on monarchy<br />

Clearly, Arthur’s death in childhood meant<br />

the monarchy took a different path in the<br />

500 years since, but this would have<br />

greater implications than simply the names<br />

on the family tree. Mary Queen of Scots,<br />

Bloody Mary and Elizabeth I all ascended<br />

to the throne in the century following<br />

Arthur’s death, the first instances of a true<br />

female monarchy in England, not just<br />

disputed claims such as Queen Matilda<br />

and Boadicea, as remarkable as those two<br />

women were. The late Tudor period set the<br />

precedent for great success for female<br />

rulers, especially Elizabeth’s 44-year-long<br />

reign, in which huge swathes of the British<br />

Empire was gathered. The ‘Golden Age’ of<br />

poetry, music, and literature (not to<br />

mention piracy and colonization) could be<br />

said to have stemmed from Elizabeth’s<br />

relative leniency towards freedom of<br />

expression and her funding Francis Drake<br />

and Sir Walter Raleigh’s expeditions to<br />

America and the Indies, as well as the East<br />

India Company to establish ‘British India’. It<br />

was in this era that the seeds of the<br />

Commonwealth were sown. Without<br />

Arthur’s childhood demise, female<br />

leadership may never have been accepted<br />

and the British Empire never built.<br />

All in all, Prince Arthur may have only lived<br />

for fifteen years, but he leaves behind an<br />

extraordinary legacy that spans the globe,<br />

impacting monarchies, religions, and even<br />

everyday people. One childhood had<br />

remarkable consequences.<br />

21 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

22 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

MODERNPERIOD<br />

23 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong><br />

EARLY

‘THE PRETTIEST<br />

AND DEAREST<br />

CHILD’ – WHAT<br />

DOES THE DEATH OF<br />

JOHN EVELYN’S SON<br />

IN 1658 TELL US<br />

ABOUT CHILDHOOD<br />

IN 17 TH CENTURY<br />

ENGLAND?<br />

Mrs Gregory<br />

24 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

of infant and child mortality; over 12% of all<br />

children born would die in their first year. A<br />

man or woman who reached the age of 30<br />

could expect to live to 59. Historians<br />

estimate that approximately 2% of all live<br />

births in England at this time would die in<br />

the first day of life. By the end of the first<br />

week, a cumulative total of 5% would die.<br />

Another 3 or 4% would die within the<br />

month. A total of 12 or 13% would die<br />

within their first year. With the hazards of<br />

infancy behind them, the death rate for<br />

children slowed but continued to occur. A<br />

cumulative total of 36% of children died<br />

before the age of six, and another 24%<br />

between the ages of seven and sixteen. In<br />

all, of 100 live births, 60 would die before<br />

the age of 16.<br />

When we think of child mortality in the<br />

past, we often assume that, because the<br />

mortality rate was high, parents must in<br />

some way have become hardened to – that<br />

it was an expected event or way of life.<br />

Perhaps then parents did not love for their<br />

children in the way modern parents do and<br />

viewed them as dispensable. We might<br />

even translate this into thinking that,<br />

because life in the past was ‘nasty, brutish<br />

and short’, violence, cruelty and death<br />

were accepted in a way that we would not<br />

recognise now – as L P Hartley said -‘ the<br />

past is a foreign country; they do things<br />

differently there’.<br />

Child mortality rates in early modern<br />

England were, without doubt, shockingly<br />

high by today’s standards. Average life<br />

expectancy at birth for English people in<br />

the late 16th and early 17th centuries was<br />

just under 40 – 39.7 years. However, this<br />

low figure was mostly due to the high rate<br />

These are astonishing numbers. In the<br />

16th and 17th centuries, 60 out of 100<br />

children died before they reached<br />

adulthood. There's nowhere in the world<br />

today that has anything like that (the<br />

current highest rates in infant mortality<br />

rates are 121 deaths per 1000 live births<br />

compared the UK's 4.5.) In those days, no<br />

one was immune – it is well known that<br />

Queen Anne (1702-1714) had 14 children,<br />

none of which lived beyond infancy. And<br />

the diarist John Evelyn (1620-1706) was<br />

himself predeceased by 7 out of 8 children.<br />

John Evelyn was a diarist who witnessed<br />

many of the tumultuous events of the<br />

seventeenth century – civil war, the<br />

execution of the King, Oliver Cromwell’s<br />

protectorate, the Restoration, plague and<br />

fire and the Glorious Revolution. His<br />

diaries covering the years 1641-1706 were<br />

found in an old clothes-basket in 1817 and<br />

provide vivid portraits of the events of the<br />

period as well as events in his personal<br />

and family life. He was a wealthy<br />

landowner with family estates in Wotton in<br />

Surrey. He joined the Royalist army for a<br />

25 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

time but went to Italy and France to avoid<br />

the conflict and in 1647 married the<br />

daughter of the Royalist ambassador in<br />

Paris. By the time of the execution of<br />

Charles I Evelyn and his wife were back in<br />

England, and he purchased a house from<br />

his father-in-law at Sayes Court at Deptford<br />

in the East end of London. In 1658, in the<br />

depths of a harsh winter (during England’s<br />

mini ice age) a tragic event occurred – the<br />

death of his 5 year old son Richard on<br />

January 27 th . Evelyn describes it as the<br />

‘severest winter than man alive had known<br />

in England’ – bird’s feet were frozen to<br />

their prey, ‘islands of ice’ enclosed fish and<br />

even trapped people in their boats.<br />

The event is recorded in his diary and his<br />

grief is recorded vividly and poignantly -<br />

‘his ‘inexpressible griefe and affliction’.<br />

What is striking is the deep affection he<br />

had for his little boy – he describes him as<br />

‘the prettiest and dearest child, that parents<br />

had ever seen’. He mourns the beloved<br />

qualities the child possessed ‘a prodigie for<br />

Witt and understanding’ and the ‘beauty of<br />

body a very Angel’. He represented<br />

Evelyn’s ‘incredible and rare hopes’. It is<br />

also striking to note that Evelyn records the<br />

age of his child with exact precision ‘5<br />

years, 5 months and 3 days’ -<br />

remembering this was a time before the<br />

births of children were officially registered.<br />

His grief seems never ending – ‘here ends<br />

the joy of my life & for which I go mourning<br />

to the grave’.<br />

and maide’ who nursed him for<br />

‘’suffocating’ him – not deliberately but by<br />

covering him ‘too hot with blankets’ and<br />

having ‘neere an excessive hot fire in a<br />

close room’. In his grief, Evelyn asked the<br />

two doctors from London – who had not<br />

made it in time to save the little boy -to<br />

‘have him opened’ - a post-mortem in<br />

Evelyn’s house to try and determine the<br />

cause of death. This seems to have<br />

revealed something wrong with his liver –<br />

he was ‘liver growne’ and with an enlarged<br />

spleen – perhaps, this rather than the care<br />

of the maid, explains his ‘fatal symptoms’.<br />

Having identified the reasons for the tragic<br />

loss, Evelyn buried his child in the local<br />

church in Deptford, accompanied by ‘divers<br />

of my relations and friends’. He records his<br />

intention to have his body moved once<br />

Evelyn himself has died to Wotton Church<br />

where he will ‘lay his bones and mingle his<br />

dust’ with his Fathers and with his beloved<br />

son. Sadly, this never happened – Richard<br />

is still buried in Deptford.<br />

One account of one father’s grief cannot be<br />

used to conclude that parents loved their<br />

children or mourned their loss. There is<br />

much that is exceptional about Evelyn – his<br />

wealth and his intellectual background for<br />

example. However, the diary entry is a<br />

heart-breaking testament to one person’s<br />

loss and we can recognise much that lies<br />

within it.<br />

It is of course impossible to deduce what<br />

the little boy died of but what is interesting<br />

is the lengths to which Evelyn goes to try<br />

and save the child and make sense of the<br />

tragedy. He sent to London for a doctor but<br />

sadly they never made it as the ‘river was<br />

frozen’ and the carriage ‘brake by the way<br />

ere it got a mile from the house’. It seems<br />

Evelyn’s first instinct to blame the ‘woman<br />

26 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

PHILLIS WHEATLEY<br />

Matthew M, 2.3<br />

Phillis Wheatley was born around 1753,<br />

probably in Senegal or Gambia (the date<br />

and place of her birth are not documented).<br />

She was kidnapped from West Africa when<br />

she was seven and was sold as a slave in<br />

Boston. She was bought by John<br />

Wheatley, who was a wealthy Boston<br />

merchant, in August 1761, as a slave for<br />

his wife, Susanna. Phillis was in a bad<br />

state, and in fragile health. She was nearly<br />

naked and just had some dirty carpet to<br />

cover her. The captain of the slave ship<br />

thought that she was about to die, so sold<br />

her very cheaply to John Wheatley.<br />

The Wheatley’s taught her to read and<br />

write, and she was soon absorbed in the<br />

Bible, astronomy, geography, history,<br />

literature and Greek and Latin classics.<br />

She soon mastered English and caused a<br />

stir among scholars after translating a tale<br />

from Ovid, a Roman poet. She started to<br />

publish poems, her first at the age of 13,<br />

and began to receive international acclaim,<br />

especially when she published the<br />

Whitefield Elegy.<br />

When she was 18, Wheatley made<br />

advertisements in Boston newspapers for<br />

her poems. However, the Americans did<br />

not want to support literature by an African.<br />

Instead, she turned to London, where she<br />

gave one of her poems to Selina Hastings,<br />

Countess of Huntingdon, who was a<br />

supporter of the abolition of slavery. Selina<br />

Hastings instructed a bookseller to begin<br />

correspondence with Wheatley.<br />

Phillis Wheatley left for London due to a<br />

chronic asthma condition on the 8 th May<br />

1771. Her works were being welcomed by<br />

many notable people. She soon published<br />

the first volume of poetry by an African<br />

American in modern times, in London,<br />

‘Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and<br />

Moral’. This included a preface which had<br />

seventeen Boston men asserting that she<br />

had written the poems in it, after she had to<br />

defend her authorship as many colonists<br />

did not believe that she had written such<br />

outstanding poetry. After this was<br />

published, the Wheatleys freed her from<br />

slavery. She also sent one of her works to<br />

the future President, George Washington,<br />

which resulted in an invitation for her to<br />

visit him in Massachusetts.<br />

Sadly for her, Susanna Wheatley died in<br />

1774, and John Wheatley died in 1778. On<br />

1 April 1778, she married John Peters, who<br />

eventually abandoned her. She had three<br />

children, all dying in infancy. They were<br />

constantly battling poverty. Eventually, she<br />

began to fall sick. She was forced to work<br />

as a maid and lived in horrifying conditions.<br />

However, she continued to write poems,<br />

but she was unsuccessful in an attempt to<br />

find support for a second volume of poetry,<br />

and even her first volume of poetry was not<br />

published in America until two years after<br />

her death. She died on the 5 th December<br />

1784, in her early 30s, alone.<br />

27 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

28 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

29 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

THE FORCED<br />

ASSIMILATION OF<br />

NATIVE AMERICAN<br />

CHILDREN<br />

Charlotte M, L6ARD<br />

Native Americans inhabited what is now<br />

known as the US for thousands of years<br />

before the first white settlers arrived in the<br />

1600s. Their land was stolen, and they<br />

were stripped of their culture. This was all<br />

at the hands of the US government which<br />

allowed and encouraged white settlers to<br />

take increasing amounts of land from<br />

natives, pushing them onto governmentassigned<br />

reservations. The government did<br />

everything it could to assimilate Native<br />

Americans into mainstream European-<br />

American culture, including taking their<br />

children.<br />

Starting in the late 1800s native American<br />

children were ripped away from their<br />

families and taken to government-run<br />

boarding schools. This was a massive<br />

federal project which separated thousands<br />

of native children from their parents. At its<br />

peak, there were over 350 of these schools<br />

indoctrinating children with US patriotism.<br />

The end goal was to completely eradicate<br />

native culture and replace it with white,<br />

Christian customs to achieve US<br />

expansion and fulfil manifest destiny. The<br />

boarding schools allowed the government<br />

to control the next generation of native<br />

people making it easier for them to be<br />

integrated into white America. It was also a<br />

way of separating native children from their<br />

land whilst the army encroached further<br />

onto tribal land through war.<br />

Once a native child arrived at a boarding<br />

school their cultural identity was taken from<br />

them. The schools confiscated all signs of<br />

tribal life, cut their braids, and gave each<br />

child a new ‘white’ name. Students were<br />

also forbidden from speaking their native<br />

languages and practising any traditions.<br />

Breaking any of these rules was cause for<br />

punishment which could include<br />

confinement, deprivation of food, or<br />

corporal disciple. Another way in which the<br />

schools tried to convert students was by<br />

forcing them to celebrate ‘white’ American<br />

holidays. For example, they had to<br />

celebrate thanksgiving which they were<br />

told was a celebration of ‘good’ native<br />

Americans aiding the pilgrim fathers. In<br />

addition to this, on Memorial Day students<br />

had to decorate the graves of US soldiers<br />

who had killed their ancestors and, in some<br />

cases, had killed their own fathers.<br />

The schools spent half the day teaching<br />

academic subjects and the other half on<br />

industrial training. Aside from the typical<br />

lessons, the boarding schools taught the<br />

importance of private property, material<br />

wealth, democracy, and monogamous<br />

nuclear families. This was in attempts of<br />

instilling traditional white American values<br />

into the children. Another aim of the<br />

schools was to convert the children to<br />

Christianity so there was heavy religious<br />

training. This involved lessons on the bible,<br />

emphasising the dangers of sin and<br />

encouraging Christian values. It caused<br />

30 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

many schools to keep boys and girls apart<br />

to allow them to have control over<br />

relationships. In some schools, girls were<br />

locked in their rooms at night, which put<br />

them in severe danger as they were unable<br />

to escape even in emergent situations.<br />

When not attending lessons, children<br />

received industrial training. Girls learnt to<br />

cook, clean, and sew. Whilst boys learnt<br />

the skills needed for blacksmithing,<br />

shoemaking and farming. This was a way<br />

of ensuring the schools were self-sufficient,<br />

rather than being maintained by external<br />

efforts. It also prepared the students for<br />

outing programmes in which they were<br />

sent away to white families to provide<br />

cheap child labour. The treatment of<br />

students in schools as well as the outing<br />

programmes led to serious accounts of<br />

neglect, abuse and even death.<br />

Death rates in boarding schools were high.<br />

This was a result of numerous factors<br />

including disease, abuse, and suicide. The<br />

unsanitary conditions and overcrowding<br />

fuelled the spread of communicable<br />

diseases such as influenza, trachoma,<br />

smallpox, and measles. These diseases<br />

massively affected students as they were<br />

already weakened by trauma and limited<br />

food rations. In 1899, there was a measles<br />

outbreak in the Phoenix Indian school<br />

which reached epidemic proportions with<br />

325 cases of measles, 60 cases of<br />

pneumonia and 9 deaths in ten days. A<br />

significant number of children also died on<br />

outing programmes as the strenuous<br />

labour and abuse became too much. A lot<br />

of these tragic deaths were ignored, and<br />

parents were rarely notified. Schools had<br />

their own cemeteries and students often<br />

built their classmate's coffins.<br />

The Carlisle Indian Industrial school was<br />

the first and most well-known offreservation<br />

boarding school. It was opened<br />

in 1879 and became the blueprint for<br />

native boarding schools across the US.<br />

The school is now the US army war<br />

college, and it has nearly 200 native<br />

children buried at the entrance. In the<br />

schools’ early years more students died<br />

than graduated, their bodies being buried<br />

on site. Parents petitioned to have their<br />

children’s bodies sent home, but the school<br />

refused. The school's disregard for the<br />

dead children can be seen in the fact that<br />

the death records are incomplete and all<br />

files for boys with the last names ‘l’ through<br />

‘z’ are missing. In addition, many of the<br />

children’s bodies are still missing. For<br />

example, Ernest White Thunder, the 13-<br />

year-old son of a Rosebud tribal leader<br />

was severely sick while at Carlisle and<br />

instead of being sent home he died there.<br />

His father then asked for the return of his<br />

body but was denied. He instead asked if<br />

they could at least place a headstone over<br />

his grave, but this request was also denied.<br />

It is still not known where Ernest is buried.<br />

This is just one example of parents who<br />

were forced to send their children away,<br />

only to never see them again. Now many<br />

tribes are pursuing justice for the families<br />

and are seeking the return of their children,<br />

who currently remain prisoners even in<br />

death. Arapaho reclaimed its first children<br />

in 2017 and other tribes have begun to<br />

follow suit.<br />

As one can imagine there was significant<br />

resistance from native Americans<br />

31 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

egarding off reservation boarding schools.<br />

However, this became more difficult in<br />

1891 when the government passed a lawmaking<br />

attendance compulsory for native<br />

children. Parents who refused to send their<br />

children to the schools could be imprisoned<br />

and deprived of resources such as food<br />

and clothing, which were already scarce on<br />

reservations. Officers were also sent to<br />

forcibly take children from reservations. In<br />

response, native children resisted by<br />

running away, refusing to work, and<br />

speaking their languages in secret. In 1893<br />

pressure once again increased to keep<br />

native children in boarding schools with<br />

increasing penalties for resistance. For<br />

example, a group of Hopi men refused to<br />

send their children to a boarding school<br />

and as a result 19 of them were taken to<br />

Alcatraz Island, a thousand miles away<br />

from their families and were imprisoned for<br />

a year. This showed the extent to which<br />

the government were willing to go, to<br />

corrupt native children with their ideals.<br />

Native communities continued to protest<br />

for the right to educate their own children,<br />

but it wasn’t until 1978 that they won the<br />

legal right to prevent family separation.<br />

However, the government found a new<br />

way to assimilate native Americans<br />

through adoption. Children were funnelled<br />

into the child welfare system and the Indian<br />

Adoption Project intentionally placed them<br />

with white families. The only real change<br />

before this was in 1928 after the<br />

government commissioned the Meriam<br />

report to give an update on native<br />

American affairs. It criticised the schools’<br />

deteriorating conditions and the heavy<br />

manual labour children had to endure. It<br />

highlighted the fact the students were<br />

hungry, sick, demoralised, and subject to<br />

harsh physical punishments. Although this<br />

only led to a minor change which included<br />

better funding for food and clothing. The<br />

report had urged the closure of boarding<br />

schools, but they persisted as the<br />

government was yet to fulfil its goal of<br />

eradicating all native American culture.<br />

Centuries after the conflict started<br />

congress, in 2009, finally passed a<br />

resolution of apology to Native Americans<br />

directly addressing the cruelty of boarding<br />

schools. However, this doesn’t make up for<br />

the suffering of Native American children,<br />

many of whom are still buried beneath the<br />

schools that abused them.<br />

Native American boarding schools stripped<br />

children of their language, customs, and<br />

culture. The government allowed the<br />

abuse, neglect, and death of innocent<br />

children in the name of westward<br />

expansion. They held native American<br />

children, hostage, in exchange for land<br />

cessions, breaking the bonds between<br />

parents and their children. By 1900, threequarters<br />

of all native children had been<br />

enrolled in boarding schools making it<br />

almost impossible for native culture to be<br />

preserved. Native languages began to die<br />

out by the 20th century as generations of<br />

children had been forced to use English.<br />

Although the government failed to<br />

completely eradicate native American<br />

cultures as they had hoped, the impacts<br />

the boarding schools had are devastating<br />

and continue to be seen today.<br />

32 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

HOW SIGNIFICANT<br />

WAS THE 1870<br />

EDUCATION ACT?<br />

Joe Scragg (OA)<br />

The granting of the vote to the working<br />

class for the first time in 1867 led the<br />

government to implement policy to ensure<br />

that the working class were educated.<br />

Therefore, following lobbying action from<br />

the National Education league, this led to<br />

the passage of the Education Act in 1870,<br />

designed by William Forester. This was the<br />

first time that the government had granted<br />

legislation on education. This article will<br />

assess the significance of the 1870<br />

Education Act in the areas of compulsory<br />

education, the secularisation of schools,<br />

the accountability of schools and setting a<br />

precedent for future Acts. Overall, the<br />

Education Act was only of real significance<br />

in the long term due to the fact it set a<br />

precedent for future acts.<br />

Despite the fact that the Education Act<br />

introduced the idea of compulsory<br />

education, this was not of great<br />

significance. The Education Act did ensure<br />

that free education was available for every<br />

child from the ages of 5-12. This is<br />

because the Act included a provision that<br />

for parents that could not afford to pay<br />

school fees this would be covered by the<br />

state. However, before 1870 availability of<br />

education was just one of the problems<br />

that needed to be tackled. Of those at<br />

school in 1861, before the passage of the<br />

Act, most attended for less than 100 days<br />

a year. This was due to the need for many<br />

children to work in industrial factories.<br />

Therefore, children missing school was a<br />

major problem before the Act. However,<br />

despite the Act aiming to tackle this, it<br />

failed to do so as school attendance due to<br />

children having to work was still a problem<br />

due to children working. This can be shown<br />

by the fact that in the 1890s attendance<br />

was still only at 82% for children aged 5-10<br />

and in 1901, 300,000 children aged 5-12<br />

still held jobs. The biggest issue however<br />

with the legislation was that it did not<br />

actually make school attendance<br />

compulsory, it only allowed for school<br />

boards to introduce laws to make school<br />

attendance compulsory. Only 40% of the<br />

population lived in a school district that had<br />

compulsory attendance, showing that<br />

boards did not vote for compulsory<br />

attendance. Indeed, the issue of<br />

compulsory education was not solved by<br />

the Act as is shown by the 1876 Royal<br />

Commission on Factory Acts report, which<br />

stated that child labour was still continuing<br />

due to the lack of compulsory education. It<br />

was not until the 1880 Act that compulsory<br />

education was introduced for children<br />

between the ages of 5-10. Therefore, due<br />

to the fact that compulsory education was<br />

not introduced till further Acts, the greatest<br />

33 | G ateway <strong>Chronicle</strong>

significance of the Act came from setting a<br />

precedent for future acts.<br />

Furthermore, the 1870 Education Act had<br />

limited significance in the area of the<br />

secularisation of schools. This is because<br />

the Act introduced non-denominational<br />

religious teaching to schools and allowed<br />

for parents to withdraw their children from<br />

religious education in non-church schools.<br />

Before the 1870 Act most children<br />

attended schools set up by the church.<br />

This was due to the fact that from 1833 the<br />

government gave grants to these church<br />

schools. Due to the passage of the 1870<br />

Education Act this allowed schools to be<br />

set up by school county boards, which<br />

were to be free from the church and were<br />

to teach religious education in a nondenominational<br />

method. Moreover, the Act<br />

gave provisional funding for schools to be<br />

set up as it allowed school boards to use<br />

local rate-payers to set up new schools.<br />

However, the Act was not as significant as<br />

it could have been in dealing with the<br />

secularisation of schools due to the<br />

Christian principles of then Prime Minister<br />

William Gladstone. This meant that a<br />

compromise instead had to be struck with<br />

the Church of England. Church schools<br />

were exempt from teaching religious<br />

education in a non-denominational method.<br />

Often to save funding school boards would<br />

simply allocate additional government<br />

funding to pre-existing church schools to<br />

create new places for children. This was as<br />

opposed to building new schools, which<br />

would be exempt from religious teaching.<br />

For example, between 1870-1885 the<br />

number of Church of England schools rose<br />

from around 6,300 to around 11,800 in<br />

England. The number of Catholic schools<br />

rose from 350 to 892. This meant that<br />

many of the children who began attending<br />

schools following the passage of the Act<br />

went to schools run by the Church. This<br />

meant that although there was some<br />

secularisation of schools caused by the<br />

1870 Education Act, the change was not<br />

as significant as it could have been.<br />

Therefore, the only real significance of the<br />

1870 Education Act was in setting a<br />

precedent for future acts.<br />

Moreover, the 1870 Education Act had<br />

some limited significance in making<br />

schools more accountable to the<br />

government. This is because the Act led to<br />

school boards being set up in each council,<br />

which were to be responsible for inspecting<br />

each school and ensuring they met the<br />

minimum government standards of the<br />

time. The Act meant that the country was<br />

divided into 2500 school districts and each<br />

would have responsibility for schools in the<br />

area. The boards themselves were<br />

accountable as they were voted for by the<br />