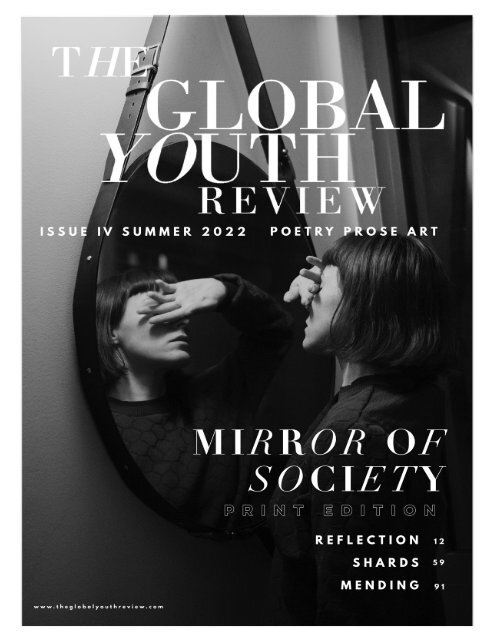

ISSUE IV: Mirror of Society

"Mirror of Society" is The Global Youth Review's fourth issue, which revolves around themes of social injustice, inequity, and inequality. We warmly welcome you into a space filled with riveting prose, poetry, and photography from creators across five continents. Designed by Sena Chang

"Mirror of Society" is The Global Youth Review's fourth issue, which revolves around themes of social injustice, inequity, and inequality. We warmly welcome you into a space filled with riveting prose, poetry, and photography from creators across five continents. Designed by Sena Chang

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

PRESENTING <strong>ISSUE</strong> FOUR<br />

-<strong>IV</strong>-<br />

FOUR<br />

-<strong>IV</strong>-<br />

THE GLOBAL YOUTH REVIEW

2 0 2 2<br />

<strong>ISSUE</strong> <strong>IV</strong> 2022 Y.<br />

M I R R O R<br />

O F S O C I E T Y<br />

T H E G L O B A L Y O U T H<br />

R E V I E W<br />

EDITORIAL STAFF<br />

Ibra Aamir<br />

Dua Aasim<br />

Abdulmueed Balogun<br />

Sena Chang<br />

Steven Christopher McKnight<br />

Lisa Degens<br />

Joshua Ellis<br />

Zo Estacio<br />

Ella Fox-Martens<br />

Rowan Graham<br />

Arianna Harris<br />

Talha Hasan<br />

Bianca J<br />

Ziqing Kuang<br />

Gabrielle Loren<br />

Krittika Majumder<br />

Ivaana Mitra C.<br />

Shreya Raj<br />

Avantika Singh<br />

Helena V<br />

Lake Vargas<br />

George White<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Adrija Jana<br />

Alex Shenstone<br />

Anna Nixon<br />

Anoushka Swaminathan<br />

Arbër Selmani<br />

DC Diamondopolous<br />

Eneida P. Alcalde<br />

Fasasi Abdulrosheed Oladipupo<br />

Felix Otis<br />

Halle Ewing<br />

Ilana Drake<br />

Jaiden A<br />

Jen Ross<br />

Katherine Ebbs<br />

Leela Raj-Sankar<br />

Mantz Yorke<br />

Matt Hsu<br />

Natasha Bredle<br />

Oladejo Abdullah Feranmi<br />

Ray Zhang<br />

Rebecca Colby<br />

Sandra Kolankiewicz<br />

Sheeks Bhattacharjee<br />

For advertising enquiries contact: theglobalyouthreview@gmail.com<br />

Cover Art: Milada Vigerova<br />

Magazine Designer: Sena Chang<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

5<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

A table <strong>of</strong> contents and a letter from<br />

the founder —<br />

1<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Pulling back the curtains <strong>of</strong><br />

society —<br />

2<br />

REFLECTION<br />

Shattered fragments that make up<br />

the mirror <strong>of</strong> society —<br />

3<br />

SHARDS<br />

Mending the shattered; healing from<br />

the broken shards<br />

4<br />

MENDING<br />

Featured writers and<br />

artists —<br />

5<br />

CLOSURE<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

6

TABLE OF<br />

CONTENTS<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM | LITERARY MAGAZINE<br />

8<br />

EDITOR'S LETTER<br />

WRITTEN BY SENA CHANG | A note <strong>of</strong><br />

gratitude to all editors, contributors, and<br />

team members involved<br />

17 GROWTH<br />

WRITTEN BY NATASHA BREDLE | A freeverse<br />

poem detailing one's growth after a<br />

series <strong>of</strong> tribulations in life<br />

22<br />

THE VIRUS<br />

WRITTEN BY ADRIJA JANA | A powerful<br />

poem placing emphasis on the centuries-long<br />

virus <strong>of</strong> racism<br />

102<br />

25<br />

THE LOCKET<br />

WRITTEN BY ILANA DRAKE | An bittersweet<br />

free-verse poem focusing on<br />

themes <strong>of</strong> loss and nostalgia<br />

126 CONTRIBUTORS<br />

A comprehensive list <strong>of</strong> all 23 contributors<br />

<strong>of</strong> the magazine, with biographies that<br />

provide further insight into their craft<br />

70<br />

72<br />

88<br />

95<br />

77<br />

THE MESTIZA<br />

BURDEN<br />

WRITTEN BY HALLE EWING | A story<br />

grappling with themes <strong>of</strong> identity loss and<br />

ostracization<br />

BOTTLE BABY<br />

WRITTEN BY MATT HSU | A short story<br />

that describes a reality where babies are<br />

sold, covering themes <strong>of</strong> racism, commodification,<br />

and human trafficking.<br />

WOULD RECOGNIZE<br />

WRITTEN BY SANDRA KOLANKIEWICZ | A<br />

poem focusing on the importance <strong>of</strong> individuality<br />

in a world filled with preordained<br />

assumptions<br />

32 WED<br />

WRITTEN BY JEN ROSS | A poignant story<br />

highlighting the issue <strong>of</strong> child marriage<br />

through the portrait <strong>of</strong> a young girl<br />

60<br />

LIFE IS A STAGE!<br />

WRITTEN BY SHEEKS BHATTACHARJEE |<br />

A critique <strong>of</strong> the growing disaffection and<br />

disconnect present amongst members <strong>of</strong><br />

our society<br />

JUDGEMENT DAY<br />

WRITTEN BY JAIDEN A. | A piece exploring<br />

the inadequacies and failures <strong>of</strong> the<br />

modern criminal justice system through a<br />

short story<br />

COVER ART<br />

The cover art for this issue used<br />

a photograph taken by Milada<br />

Vigerova. She can be found on<br />

Instagram at @milivigerova.<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

7<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

BY<br />

SENA CHANG<br />

Editor’s<br />

LETTER<br />

T<br />

here is no doubt that the modern<br />

political system is shrouded by<br />

corruption, cronyism, and nepotism—<br />

all hidden within the everyday<br />

idiosyncrasies <strong>of</strong> life. From Putin's unprovoked<br />

invasion into Ukraine to the January 6th Capitol<br />

riots that threatened the very concept <strong>of</strong><br />

democracy within the U.S., 2022 has blatantly<br />

revealed the many inefficiencies and corruptive<br />

structures present within the political system<br />

that masquerade themselves as justice, equity,<br />

and other morales. The many issues that plague<br />

our politics and justice system have come out <strong>of</strong><br />

the shadows this year, demonstrating to us the<br />

fragility and temporariness <strong>of</strong> democratic ideals.<br />

Yet, many issues have still remained untouched,<br />

hidden behind curtains that are rarely pulled<br />

back in modern society.<br />

In this issue, we set out to find bold<br />

writers and artists unafraid to pull back<br />

this rhetorical curtain—steadfast in their<br />

commitment to speaking truth to power and<br />

shattering traditionally hegemonic narratives.<br />

Having closely read the works <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> our<br />

contributors, I firmly believe that we have<br />

achieved this goal through the powerful<br />

storytelling <strong>of</strong> our writers and poets. Reading<br />

through this issue, you’ll see the braveness and<br />

freshness with which these selected contributors<br />

face societal issues such as child marriage,<br />

racism, and commodification. These stories<br />

collectively reach into a rawness and pr<strong>of</strong>undity<br />

rarely found in today’s society; these stories<br />

plant a seed <strong>of</strong> hope within me that someday, our<br />

society will stand upon the pillars <strong>of</strong> true justice,<br />

equity, and transparency, instead <strong>of</strong> the distorted<br />

definitions <strong>of</strong> these morales that we have created<br />

in our world today. So, without further ado, I<br />

warmly welcome you into issue four <strong>of</strong> The Global<br />

Youth Review—a space abundant with talent,<br />

rawness, and truth about the most pressing<br />

matters facing us today.<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

8

“writing<br />

is the<br />

geometry<br />

<strong>of</strong> the<br />

soul.<br />

Plato<br />

(429–347 B.C.E.)

Magazine<br />

MIRROR<br />

<strong>of</strong> SOCIETY<br />

We warmly welcome you into The<br />

Global Youth Review's fourth issue,<br />

which focuses on what lies behind<br />

the curtains <strong>of</strong> society.<br />

By THE GLOBAL YOUTH REVIEW<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

10

<strong>ISSUE</strong> <strong>IV</strong><br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

11<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

BY ERICK BUTLER

CHAPTER<br />

reflection<br />

REFLECTION<br />

" One <strong>of</strong> the most destructive things<br />

that's happening in modern society<br />

is that we are losing our sense <strong>of</strong> the<br />

bonds that bind people together."<br />

Alexander McCall Smith<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

12

BY SNOWSCAT

CHAPTER<br />

"...rocking gently back and forth /<br />

in the wake / <strong>of</strong> our wasted youth,<br />

lost..."<br />

"Growth"<br />

Natasha Bredle

BY JONATHAN CHEN

G R O W<br />

T<br />

H<br />

G R O W<br />

T<br />

H<br />

G R O W<br />

T<br />

H<br />

WAS THE WORLD EVER MEANT<br />

TO BE TOUCHED BY OUR<br />

CALLOUSED HANDS?<br />

Natasha Bredle<br />

BY AARN GIRI

POETRY<br />

GROWTH<br />

By NATASHA BREDLE<br />

Battle wounds displaced, we are<br />

a myriad <strong>of</strong> lovers, seekers in/out <strong>of</strong> touch<br />

with the world, but tell me<br />

was the world<br />

ever meant<br />

to be touched by our calloused hands?<br />

Purpled fingers, bleeding cuticles<br />

charred nails that corresponded with<br />

the fruit <strong>of</strong> our labors, dazzling shades <strong>of</strong><br />

sugar, citrus, everything<br />

in moderation has never failed,<br />

only we fail to see this<br />

when we mistake more for more, or<br />

less for more, or<br />

either reciprocal.<br />

Pursuing extremes, time slips<br />

through the cracks <strong>of</strong> our fingers to leave us<br />

rocking gently back and forth<br />

in the wake<br />

<strong>of</strong> our wasted youth. Lost<br />

laughter, fostering lips abridged<br />

dopamine receptors, abundant eyes<br />

caged seeds, fertile which might have become<br />

great forest trees destined one day to shade<br />

a weary traveler, or merely<br />

pump necessity into the atmosphere.<br />

Recognition is the greatest gift<br />

we give those unfulfilled possibilities <strong>of</strong> the past—<br />

recognition, and a promise<br />

to not fling the future behind us<br />

in the same blind-sighted way.<br />

The scars peppering our skin will remind us, striving<br />

for our different path, intending<br />

to see the sun that set too early<br />

rise again.<br />

We were birthed from the shadows.<br />

We will not turn our ancestors into the enemy,<br />

but allow their enlightenment to cascade<br />

over us like the light <strong>of</strong> day:<br />

barely perceivable, but overwhelming.<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

17<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

POETRY<br />

WAKING UP<br />

AFTER A PANIC ATTACK<br />

By NATASHA BREDLE<br />

Invisible clouds <strong>of</strong> cotton<br />

amass beneath your eyes, materialized<br />

during the night perhaps to soak up those inconsolable tears,<br />

and they did the job, but now your face<br />

might as well have been in a fist fight, bulging bags<br />

blurring your vision. But what is there to see<br />

when all you feel is the aftermath<br />

<strong>of</strong> your flight or fight perception?<br />

The heat, the bile rising in your throat,<br />

heart racing with palpitated rhythm. God, not again.<br />

Forget, forget, forget.<br />

But how can you carry on when the memory<br />

lies just behind the bend, along with the certainty<br />

<strong>of</strong> attacks planned ahead?<br />

Look around you, look,<br />

did the sun still rise? Can you feels its rays on your skin,<br />

oblivious to the terror that rattled your bones<br />

in the precedent hours <strong>of</strong> night?<br />

Is the Earth still spinning?<br />

Is your mother still driving to work at a school<br />

whose hallways are patrolled by buff men<br />

with tasers and badges?<br />

Are politicians still hollering on the morning news program?<br />

Are children around the world still huddling<br />

in the dusky corners <strong>of</strong> their homes, sucking their fingers<br />

until red welts appear?<br />

Are men still pacing jail cells, running their fingers<br />

along cold bars, struggling to recall the feel <strong>of</strong> sunshine?<br />

Are boys and girls still waking up in emergency rooms<br />

with their wrists stitched up like paper maché,<br />

tasting air and realizing<br />

they never wanted to stop breathing?<br />

Yes, the answer is always yes.<br />

You carry on when you keep moving.<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

18

BY ORFEAS GREEN

BY ANNIE SPRATT

POETRY<br />

FEMININE<br />

By ADRIJA JANA<br />

If I wear my Father's shirt, do I become a boy?<br />

If I cut my hair short, do I cease to be Feminine?<br />

What is Feminine anyway?<br />

Must Femininity stand with downcast eyes and cover her head?<br />

Must Femininity lower her voice and sit in a particular way?<br />

Must Femininity sweat in the kitchen and cater to the Man's every whim?<br />

Must Femininity close her eyes, and cast aside every dream?<br />

Must Femininity not protest for her due, a placard in hand?<br />

Must Femininity not vote in a democracy, or as a candidate in an election stand?<br />

If that is what Femininity is to you,<br />

Then I'm sorry to say<br />

I'm not Feminine<br />

And you, my dear critic, are not suited to the present times.<br />

And yes, I'm a girl<br />

But I don't need to prove that<br />

By wearing clothes you choose<br />

By sitting the way you want me to<br />

By wearing my hair the way you ask<br />

If I wear my father's shirts, you say<br />

People might start to think I'm gay<br />

So what if they do?<br />

I know myself<br />

And for me, that's enough.<br />

And being gay- that is not something bad<br />

It's your thoughts that are caged in a box.<br />

I don't need your validation, nor your advice<br />

I choose to exercise my freedom <strong>of</strong> choice, my Right<br />

And I don't need to be feminine for love<br />

And I will not change myself<br />

For those who truly love me<br />

Will accept me for who I am.<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

21<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

POETRY<br />

THE<br />

viRus<br />

"It's an epidemic that been ravaging,<br />

Not a year or two but for centuries now..."<br />

By ADRIJA JANA<br />

Icould be a mother, a daughter, a sister, a wife,<br />

Or a father, a son, a brother, a husband,<br />

I might be a little one that's yet to walk<br />

Or established in my own job.<br />

But none <strong>of</strong> it matters<br />

For when you look at me,<br />

My skin colour is all you see.<br />

No, you're not too open about it<br />

But oh so subtle!<br />

And you did notice:<br />

My skin tone is a shade too dark.<br />

The way you shifted to the other end <strong>of</strong> the train seat,<br />

The way you shifted the resume to the discarded pile,<br />

Just by looking at the picture<br />

Oh! you definitely did notice.<br />

It's an epidemic that been ravaging,<br />

Not a year or two but for centuries now<br />

And the virus has now perfected its art.<br />

No mask, no hand wash, no sanitiser<br />

Can now stamp it out<br />

Because it is now comfortably settled<br />

Into the deepest recesses.<br />

Of your heart, mind and soul.<br />

Into the very stem cells <strong>of</strong> your brain<br />

So that you see feel and act upon the skin colour,<br />

And not upon the thought, merit or feeling<br />

Of the person before you<br />

And you and only you<br />

Can root this virus from within yourself<br />

Of course if you're willing.<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

22

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

23<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

By CARSON ARIAS

POETRY<br />

I A M<br />

THE MODERN<br />

REINCARNATION OF OPHELIA<br />

By ANNA NIXON<br />

I am the modern reincarnation <strong>of</strong> Ophelia<br />

And I will not be hearing you<br />

If I am running down the road<br />

And you wind your window down<br />

to tell me to run faster<br />

Take this lavender you bastard<br />

I am the modern reincarnation <strong>of</strong> Ophelia<br />

I was just picking up a fork<br />

So why the f**k did you stroke my hand<br />

Did you have something slightly less charming planned?<br />

Take this clover, cuz your life is a sham<br />

I am the modern reincarnation <strong>of</strong> Ophelia<br />

And I will not be going near<br />

A man who comments on the smell <strong>of</strong> my hair<br />

As his breath moistens my ear<br />

With god knows what disease<br />

Take an ice plant because I hope you freeze<br />

I am the modern reincarnation <strong>of</strong> Ophelia<br />

And please don’t ever make me fear<br />

Opening messages when your name appears<br />

Just in case, instead <strong>of</strong> a text it is<br />

A sickening picture <strong>of</strong> your d**k<br />

I am the modern reincarnation <strong>of</strong> Ophelia<br />

And I just went for some fresh air<br />

When you stopped me in the park to stare<br />

And ask if I would gladly share<br />

A better view <strong>of</strong> my bunda<br />

Your flower’s ten feet in the ground that I wish you were under<br />

I am the modern reincarnation <strong>of</strong> Ophelia<br />

And why would you tell me that you’ll give<br />

Me milk everyday cuz you know where I live<br />

Stalking is not something easy to forgive<br />

So take this foxglove, and garnish your morning milk with it<br />

I am the modern reincarnation <strong>of</strong> Ophelia<br />

On vacation I was chilling when<br />

You grabbed my arse from behind<br />

Thinking I wouldn’t see or mind<br />

Then turned to your friends and smiled wide<br />

Take this ivy and eat it, it’s deadly inside<br />

I am the modern reincarnation <strong>of</strong> Ophelia<br />

And don’t scapegoat me cuz I’m not mad<br />

I am the modern reincarnation <strong>of</strong> Ophelia<br />

And the patriarchy is my controlling dad<br />

Take the rose without the flower, cuz you’re a prick<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

I am the modern reincarnation <strong>of</strong> Ophelia<br />

And I am beautiful but I don’t need you to tell me that<br />

I am the modern reincarnation <strong>of</strong> Ophelia<br />

And I’m not drowning because <strong>of</strong> any lad<br />

24

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

65<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

By SAEED SIDDIQUI

RECOVERY<br />

By NATASHA BREDLE

BY<br />

NATASHA BREDLE<br />

By LOGAN WEAVER<br />

it is inexplicable<br />

the handprints on my body:<br />

one per thigh, face smothered, stomach marred<br />

until<br />

i lift up my hands and see the blood painting my skin.<br />

the ancient scrolls say to cry out to the sky:<br />

i returned your stars,<br />

when will you shine on me again?<br />

upon its muted response, the waiting commences.<br />

throw in a dabble <strong>of</strong> sleepless nights, go searching<br />

for estranged serotonin and when i repeatedly<br />

turn up empty, may the realization emerge<br />

that i have found other necessities,<br />

such as<br />

the words to describe this ambivalent recovery.<br />

‘better’ is not the pellucid term they exalt it to be:<br />

will i recognize you when we meet?<br />

many welcome strangers have passed through here,<br />

as well as the hostile, whose aura lingers<br />

like a curated scent.<br />

pressed wisteria or burnt candle wicks,<br />

alluring, but with the capacity<br />

<strong>of</strong> untamable destruction which i<br />

have wrought on myself:<br />

water, please wash away these crippling stains.<br />

i promise i will not forget.<br />

for now the handprints remain,<br />

but the sky gives me solace. the blood<br />

runs through my veins, hailed as remnant <strong>of</strong> the war.<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

27<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

Poetry<br />

on my<br />

identity<br />

By ANOUSHKA SWAMINATHAN<br />

perhaps i am a demon<br />

perhaps i am here, with my dirty claws and brittle teeth and mangled<br />

hair<br />

to ruin everyone’s life<br />

perhaps the reason that the way that i love upsets some is because<br />

they are perfect and god-fearing and pure and devoted and nothing in any<br />

way like me<br />

perhaps the reason that my in-between, my out-<strong>of</strong>-the-box is so terrible<br />

to some is because<br />

i go against their nature<br />

perhaps the reason that my skin, my history, என் மக்கள்* create such a<br />

tangible hatred in some is because<br />

we should have stayed in our own nation, browns and whites should not<br />

mix<br />

or perhaps those people are just overgrown bullies<br />

who can’t fathom the existence <strong>of</strong> those<br />

different than them<br />

perhaps i am the god, the monarch, the deva<br />

perhaps my ‘kind’ should do what we want without taking into consideration<br />

what will be said by a bigot<br />

perhaps our demonic nature is just that to someone who has never left the<br />

seat near their fireplace, staring into the flames with our imprints in their<br />

gaze<br />

*என் மக்கள், pronounced ‘en makkal’, means ‘my people’ in Tamil<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

28<br />

By VLADISLAVE NAHORN

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

29<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

By VALENTIN BEAUVAIS

POETRY<br />

What the Night<br />

Means to a Refugee<br />

WBy FASASI ABDULROSHEED<br />

OLADIPUPO<br />

Another room is ready to move my old memories<br />

and latest griefs.<br />

This is what I do all night, moving my childhood and<br />

its mistakes, my womanhood<br />

Before I become an outcast, moving my widowhood<br />

into the night,<br />

What used to caress me; s<strong>of</strong>t full <strong>of</strong> songs, hard full<br />

<strong>of</strong> sensation<br />

And these taking spirits out <strong>of</strong> my body now, tiring<br />

my existence.<br />

A carb in my pajamas, every falling star like a child<br />

who left without<br />

Owning a name; I have named them all Ibrahim,<br />

every moonless night<br />

Like my husband taking away the light, like the<br />

beginning <strong>of</strong> all these turmoil.<br />

Every night is a new insurgent, a fresh war<br />

somewhere in my head.

PROSE<br />

Jen Ross<br />

WED<br />

"Nahla's mother...put her to bed<br />

by herself to give Nahla the earthshattering<br />

news: “Nahla, my dear,<br />

you are going to be wed.”<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

32

By THATSELBY

PROSE<br />

Staring up through the tall grasses at the clouds rolling by, Nahla<br />

takes a deep breath, inhaling the fragrance <strong>of</strong> the date palms<br />

swaying gently in the breeze above her. The scent reminds her <strong>of</strong><br />

afternoons playing in the fields with her brothers, and the sweet<br />

date pastries her mother made a few weeks ago for her 13th birthday.<br />

Savoring this rare time alone, lying still in the morning<br />

tranquility, she digs her fingers into the earth beneath her, palming its<br />

freshness, as if feeling it for the last time. Her brow furrows. She knows<br />

today is the day everything will change. Today is her wedding day.<br />

***<br />

Nahla could usually be found in these fields, running around<br />

playing games with her brothers, or sometimes with friends from<br />

her village, Al Roda, on the banks <strong>of</strong> the mighty Nile River in Upper<br />

Egypt. Her family lived on the outskirts <strong>of</strong> town, on a small plot that<br />

received just enough river run-<strong>of</strong>f to cultivate a variety <strong>of</strong> vegetables<br />

and dates, which they sold at the village market. Along with her two<br />

brothers, Nahla would help with the planting and harvesting, between<br />

her studies.<br />

Although it hadn’t always been so, all three siblings had<br />

attended school for the past few years. It was the part <strong>of</strong> her day that<br />

Nahla looked forward to most. There, she could play jump-rope and<br />

handkerchief games with her many friends in the schoolyard, and<br />

they would tease and whisper to each other about boys whenever the<br />

teachers weren’t within earshot. But mostly, Nahla loved her classes –<br />

science, history, and geography in particular – which made her dream<br />

<strong>of</strong> what life was like in the world beyond her village.<br />

She’d once pr<strong>of</strong>essed that her favorite book was her geography<br />

textbook – which garnered a chorus <strong>of</strong> laughter from her classmates<br />

and an approving smile from her teacher. Nahla would <strong>of</strong>ten leaf<br />

through it when she’d finished her schoolwork and was waiting for the<br />

other children to finish theirs. Its glossy pages detailed the different<br />

plants, trees, soils, and animals in Egypt and other countries around<br />

the world. Nahla had memorized their names in both Arabic and Latin<br />

– and yearned to learn more about how farmers managed their crops<br />

in other countries. She hoped this knowledge could help her improve<br />

her family’s own way <strong>of</strong> farming.<br />

This year, the harvest had not been good. Many <strong>of</strong> the plants<br />

were diseased and the rains were getting fewer and farther between,<br />

which meant ever more frequent trips to the receding riverbed to fetch<br />

water. Beyond the dates and vegetables they farmed, her mother and<br />

father had struggled to put food on the table as there was no money for<br />

milk or meat.<br />

Her parents always seemed to have worried looks etched<br />

across their faces. But that didn’t stop Nahla’s father from telling them<br />

bedtime stories about ordinary men whose hard work and persistence<br />

would be rewarded with bountiful harvests and riches beyond their<br />

wildest dreams. While her brothers always looked on wide-eyed,<br />

arguing about who would be richer when they grew up, Nahla just sat<br />

silently, wondering why her father never talked about ordinary women<br />

getting rich.<br />

A week ago, Nahla’s mother had exceptionally come<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

34<br />

By FILIPP ROMANOVSKI

PROSE<br />

to put her to bed by herself to give Nahla<br />

the earth-shattering news: “Nahla, my<br />

dear, you are going to be wed.”<br />

Although it was common for girls in<br />

her village to marry young, Nahla had<br />

hoped to be one <strong>of</strong> the lucky ones who<br />

managed to marry later.<br />

“Mother, no! Please! I want to<br />

finish school!” she protested.<br />

“That might be possible,” said<br />

her mother, frowning and looking at<br />

the floor, “but it will depend on your<br />

husband’s wishes.”<br />

“Why now?” pleaded Nahla.<br />

“Can’t we wait until I’m older, like<br />

cousin Mona? She was 18.”<br />

“I am afraid we cannot,” said<br />

her mother, no longer trying to hide the<br />

pain on her face. “You know the harvest<br />

has not been good this year. There is a<br />

man from Minya who is willing to pay a<br />

good sum.”<br />

The words were piercing.<br />

Nahla suddenly understood what it<br />

must feel like to be one <strong>of</strong> those goats<br />

at the market, and paraded around to<br />

fetch the highest price for their masters.<br />

Staring at her mother<br />

intensely, she took a deep breath to<br />

stop herself from saying something she<br />

would regret. Then her face s<strong>of</strong>tened<br />

and she sighed. She knew her family<br />

was in need. After a long pause, she<br />

reluctantly asked: “Who is he?”<br />

“Well, we know he works in a<br />

bank and he is a very respected man.”<br />

“How old is he?” was Nahla’s<br />

next question.<br />

“Does that matter?” asked her mother,<br />

defensively. “It has already been<br />

decided and your father has made<br />

the arrangements for a customary<br />

wedding.”<br />

Nahla stirred, her eyes betraying the<br />

fear brewing inside. Faced with her<br />

silence, her mother finally responded:<br />

“He is 33 years old.”<br />

Nahla gasped audibly. Ever<br />

since the day the blood had appeared<br />

in her panties, she had feared that her<br />

life would change in ways she would<br />

not welcome. It had been almost a year<br />

since that day and she was now 13.<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

35<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

PROSE<br />

She kept repeating the man’s<br />

age in her mind: 33. That was<br />

just five years younger than<br />

her father. How could she<br />

marry a man 20 years her senior?<br />

What would they have in common?<br />

What would she possibly speak to<br />

him about? She had seen girls in<br />

her village marry older men. Those<br />

girls looked so sad all the time.<br />

***<br />

A few days later, it came<br />

time to meet her husband-to-be<br />

and his family. It was a Thursday<br />

afternoon and her mother and<br />

aunts hurried her into the house<br />

after school and began brushing her<br />

hair, applying make-up for the first<br />

time, and dressing her in an<br />

elaborate gown.<br />

When Nahla caught<br />

a glimpse <strong>of</strong> herself in a<br />

mirror, her mouth dropped<br />

at the sight <strong>of</strong> herself in the<br />

long bright pink dress beaded<br />

with intricate flowers. It was<br />

stunning. She ran her fingers<br />

along the silky fabric, circling<br />

the crystalline flowers.<br />

“It is a gift from your new<br />

family,” her aunt Hiba whispered.<br />

When Nahla looked up to<br />

inspect her face she almost didn’t<br />

recognize herself. Her eyes were<br />

rimmed with dark lines and her skin<br />

looked much whiter than usual. She<br />

touched her cheek and felt a faint<br />

powder.<br />

“Do not touch!” barked<br />

her aunt Hiba. “You will ruin your<br />

makeup. It is time to go.”<br />

Her family rushed her into a car she<br />

didn’t recognize, with a driver who<br />

shuttled them to a neighborhood<br />

closer to the city. As Nahla stared out<br />

the window, the houses grew larger<br />

and more well-kept by the block.<br />

She tried to imagine the face <strong>of</strong> her<br />

husband-to-be. Might he be a goodlooking<br />

man? What if he looked like a<br />

goat? Would he be a nice man?<br />

They finally pulled into<br />

the driveway <strong>of</strong> a large two-story<br />

white house, trimmed in bright blue<br />

paint, which was believed to protect<br />

against the ‘evil eye’—a curse cast<br />

by an envious glare. Although Nahla<br />

had never been superstitious, she<br />

couldn’t help thinking to herself that<br />

she really didn’t need such protection<br />

now, for who could possibly<br />

envy a girl getting married at 13?<br />

Her parents walked her to<br />

the arched patio entrance, followed<br />

by her aunts, who had come in<br />

another car. Just past the gate, a crowd<br />

<strong>of</strong> people Nahla didn’t recognize<br />

was greeting one another excitedly.<br />

When she arrived at the front door,<br />

an older couple who looked about the<br />

age <strong>of</strong> her grandparents greeted her<br />

‘‘ ...who could possibly<br />

envy a girl getting married<br />

at 13?"<br />

warmly.<br />

“Nahla: meet your new<br />

parents,” announced her mother,<br />

smiling widely.<br />

“Hello,” said Nahla<br />

tentatively, unsure <strong>of</strong> what else to<br />

say to these strangers she was now<br />

expected to call ‘parents’.<br />

“Welcome to our family,”<br />

said the older woman, extending<br />

her arms, which were adorned in<br />

thick gold bangles, and pulling her<br />

in for a hug. Nahla got a brief whiff<br />

<strong>of</strong> her strong rose-like perfume<br />

as the woman proceeded to usher<br />

her inside the house, steering her<br />

towards an elegant long white s<strong>of</strong>a.<br />

“Please sit.”<br />

There, Nahla waited as her<br />

father came to stand next to her, and<br />

a bearded man wearing a black suit<br />

approached from the other side, to<br />

stand and face her father.<br />

“I would like to formally<br />

ask for your daughter’s hand in<br />

marriage,” the man said, in a low,<br />

husky voice.<br />

So, this was her husbandto-be.<br />

Nahla examined his dark,<br />

piercing eyes, high forehead, and<br />

long nose. He was not particularly<br />

attractive, but neither was he ugly.<br />

He was tall and looked older than her<br />

father, perhaps because <strong>of</strong> his beard.<br />

He did not shift his gaze to make eye<br />

contact with Nahla as she stared at<br />

him.<br />

A bushier-bearded Imam<br />

entered the room and began speaking<br />

<strong>of</strong> how the Prophet Muhammad had<br />

honored his wives.<br />

“Men should<br />

honor women and women<br />

should serve and honor their<br />

husbands.”<br />

As he said this,<br />

several women nodded<br />

approvingly, while Nahla<br />

gawked. How unfair was it<br />

that women also had to “serve”,<br />

rather than simply honor their<br />

husbands? she thought to<br />

herself.<br />

The Imam proceeded to<br />

ask the man if he would follow this<br />

advice. He nodded. Then he looked to<br />

her father, who also nodded to show<br />

he accepted the marriage proposal.<br />

Then he sat down next to Nahla on<br />

the long s<strong>of</strong>a, while the groom sat<br />

on his other side. Another man she<br />

did not recognize appeared with the<br />

Islamic holy book, the Qu’ran, and<br />

handed it to her father. The bearded<br />

man then placed his hand on Nahla’s<br />

father’s and they read the Fatha<br />

passage in unison.<br />

When they had finished, the<br />

man stood before Nahla, and for a<br />

split second, he met her gaze. It was a<br />

fleeting glance, but with an intensity<br />

that frightened her. Then he took<br />

her hand and mechanically placed a<br />

golden band on her right ring finger,<br />

handing her a larger ring in her left<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

36

By KATERYNA HLIZNITSOVA<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

37<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

By JOEYY LEE<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

38

PROSE<br />

hand. After an awkward pause, he<br />

motioned for her to place the ring<br />

on his finger. Nahla blushed and<br />

took his thick, hairy finger, fumbling<br />

with the ring clumsily. She’d never<br />

touched a man’s hand who was not<br />

a relative. Applause soon rang out<br />

from the dozen or so guests.<br />

Moments later, a belly<br />

dancer decked in gold sequins<br />

emerged and began swaying her hips<br />

to the ever-quickening beats <strong>of</strong> two<br />

drummers behind her. Meanwhile, a<br />

few women dressed in blue smocks<br />

entered, <strong>of</strong>fering the guests trays<br />

<strong>of</strong> fruit and flower-scented sweets,<br />

which Nahla declined. She could feel<br />

her stomach churning.<br />

“Fares! We are so happy for<br />

you!” called out an older woman that<br />

Nahla did not recognize. So, that was<br />

his name: Fares.<br />

“We thought you would never settle<br />

down,” laughed the woman, who he<br />

quieted with a stern look.<br />

The party went on for hours,<br />

without the newly engaged couple<br />

exchanging a single word. When it<br />

was time for Nahla to leave, Fares<br />

simply cocked his head politely.<br />

On their way home, Nahla’s father<br />

was the first to break the awkward<br />

silence, saying: “What a wonderful<br />

party. I think this will be a good<br />

family.”<br />

Nahla did her best to muster a smile<br />

but could not bring herself to speak<br />

the entire drive home. Staring out<br />

the window, she circled the sparkly<br />

pink flowers adorning her dress, and<br />

silently shed a tear.<br />

***<br />

Nahla did not see Fares<br />

or her new family again before the<br />

wedding.<br />

One evening, all the women<br />

and girls in Nahla’s extended family,<br />

and three <strong>of</strong> her closest friends from<br />

school, descended upon her house<br />

for Laylat Al-Hinna – a customary<br />

party to decorate the bride’s hands<br />

and feet with henna the night before<br />

the wedding.<br />

There must have been at<br />

least 50 women and girls gathered<br />

there to celebrate and wish her<br />

well. It was the first time a couple<br />

<strong>of</strong> her school friends were visiting<br />

and Nahla felt a little embarrassed<br />

by her modest two-bedroom home<br />

with sparse furnishings. But her<br />

mother-in-law had brought some<br />

fancy hanging decorations to liven<br />

the place up, and even her normally<br />

stuck-up friend Sanaa didn’t seem<br />

out <strong>of</strong> sorts.<br />

“Remember all those<br />

times we acted out tales <strong>of</strong> princess<br />

maidens and dragons at recess?”<br />

Saana reminded Nahla. “Now you<br />

will get to live your own fairytale!”<br />

she said, batting her eyelids<br />

dramatically.<br />

The pair had been school<br />

friends since kindergarten, although<br />

By ALEX CHAMBERS<br />

their parents were not. Nahla’s<br />

mother once told her that Sanaa’s<br />

family was “too high class for her”.<br />

Strange, Nahla thought, that her<br />

family was suddenly open to her<br />

marrying someone from that class.<br />

Nahla’s aunt Maryam, ever<br />

eager to be the center <strong>of</strong> attention,<br />

took it upon herself to do the henna<br />

painting. She began by tracing a<br />

delicate floral pattern surrounded<br />

by curvy, intricate designs around<br />

her wrist. The henna looked black<br />

and raised at first, but Nahla knew<br />

that when it was ready, it would leave<br />

a temporary brown die for several<br />

weeks.<br />

The girls plucked dozens <strong>of</strong><br />

sweets from stacked, shiny plates.<br />

They laughed themselves silly while<br />

playing games, then danced and<br />

sang songs. Meanwhile, the mothers<br />

and older family members clapped<br />

and took turns smoking a shisha<br />

pipe. Nahla lost herself for a while in<br />

the joy <strong>of</strong> the henna party, reveling<br />

in the rare congregation <strong>of</strong> females.<br />

She sighed and sat back to savor the<br />

feeling <strong>of</strong> safety, and love she felt in<br />

being at the center <strong>of</strong> such warmth<br />

and attention.<br />

“You are so lucky to be<br />

getting married,” crooned her<br />

10-year-old cousin Dina, who had<br />

always been close to Nahla, mostly<br />

because she defended her against<br />

an older brother’s teasing. “What a<br />

dream come true!”<br />

Reminded <strong>of</strong> what was<br />

to come, Nahla smiled awkwardly,<br />

feigning excitement. She didn’t want<br />

to seem ungrateful or reveal her<br />

feelings <strong>of</strong> impending doom. She was<br />

to wed the following day. After going<br />

to bed late, she barely slept a wink<br />

that night.<br />

***<br />

The next morning, Nahla<br />

lay still between the tall grasses near<br />

her home, staring up at the sparse<br />

clouds and savoring the tranquility<br />

and her last hours <strong>of</strong> freedom – the<br />

last hours <strong>of</strong> the life she had always<br />

known.<br />

Although she could hear<br />

voices calling for her in the distance,<br />

she dared not move. Perhaps if she<br />

stayed here, hidden between the<br />

grasses, her family wouldn’t be able<br />

to find her and the wedding would<br />

have to be called <strong>of</strong>f. What if she just<br />

rested here for a while? She was so<br />

tired and her eyelids felt heavy…<br />

Nahla had no idea how<br />

much time had passed when her<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

39<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

PROSE<br />

mother found her and angrily pulled her from the field.<br />

“Nahla, how could you? We were looking everywhere for you! The wedding<br />

starts in an hour! We need to get you dressed; we need to do your hair; we need to<br />

get to the groom’s house…” her mother shrieked.<br />

A dozen frenzied women crowded around her to dress and make her up –<br />

her aunt Hiba chastising her for the dirt beneath her nails and the grass in her hair.<br />

Meanwhile, Nahla tried to keep her eyes closed so tears wouldn’t be shed.<br />

The venue was Fares’ home again, which now looked like a flower shop –<br />

splattered with dazzling bouquets <strong>of</strong> pink peonies, cream-colored roses, and salmon<br />

dahlias. Nahla had been wowed by the engagement party decor, but this display<br />

was lavish beyond what she could have imagined. She bit her lower lip nervously as<br />

Fares appeared by a raised table in the courtyard.<br />

Clutching the protective arm <strong>of</strong> her father, Nahla took slow and careful<br />

steps toward him. Beads <strong>of</strong> sweat were forming on Fares’ forehead and he fidgeted<br />

with the sleeves <strong>of</strong> his fancy black tuxedo. Nahla had barely looked at the beautiful<br />

white gown she was wearing, but now noticed that it was so long she nearly tripped<br />

over it in her tediously high silver heels.<br />

As she reached Fares, he carefully lifted the thin transparent veil that hung<br />

over her face, running his hand gently over her forehead as he did, his first act <strong>of</strong><br />

tenderness.<br />

Fares and Nahla’s fathers stood next to them, placing their hands together<br />

and a religious <strong>of</strong>ficial man, called the shaykh, covered their hands with a white<br />

handkerchief while he read a passage from the Qur’an. He had them repeat a couple<br />

<strong>of</strong> words and then he removed the handkerchief – which made the transaction for<br />

Nahla’s hand <strong>of</strong>ficial. Nahla had watched this done before, at her cousins’ weddings,<br />

but witnessing her father gift her away in this fashion, under the guise <strong>of</strong> religion,<br />

left a deeply unsettling feeling in the pit <strong>of</strong> her stomach.<br />

This ritual was followed by an eruption <strong>of</strong> music. The clanging tambourines,<br />

blaring trumpets, and pounding drums were loud enough to compete with Nahla’s<br />

racing heart. The couple was surrounded by guests as the procession began. The<br />

band performed traditional wedding songs and the women wailed in high-pitched<br />

ululations.<br />

The new bride and groom slowly made their way towards a<br />

flower-laden stage set up with two chairs, where they were to greet their guests<br />

and pose for photographs. As they sat, without speaking, Fares handed Nahla an<br />

envelope and a small golden box which he motioned for her to slip into her purse.<br />

A few <strong>of</strong> Nahla’s friends and cousins approached to pinch her knee, for<br />

good luck in their own hopes <strong>of</strong> being the next to marry.<br />

The ceremony was everything a customary Muslim Egyptian wedding was<br />

meant to be.<br />

The party ended late into the night and Nahla was exhausted, nearly falling<br />

asleep several times. Fares led her to a bedroom in what was now her new home<br />

and laid her on the bed. Then, he began slowly undoing the buttons <strong>of</strong> her wedding<br />

dress. Gripped with fear but not wanting to <strong>of</strong>fend him, Nahla pretended to be<br />

asleep.<br />

After removing her dress, nudging, and turning her over a few times, Fares<br />

seemed to give up and quietly left the room. Despite her exhaustion, Nahla could not<br />

sleep for several hours, out <strong>of</strong> fear that he would return to her bed in the middle <strong>of</strong><br />

the night. As his wife, she would now be expected to “serve” him, in all ways.<br />

***<br />

Three months later, when Nahla came home to visit her parents, they could<br />

hardly recognize her. Her hair was disheveled and there was no longer any spark in<br />

her eyes.<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G 40<br />

E<br />

By HISU LEE

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

41<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

PROSE<br />

By CAMILA QUINTERO FRANCO<br />

Nahla did her best to stay<br />

positive despite her stormy new<br />

home, reminding herself to be<br />

grateful that she had no want for<br />

food or shelter, nor did her parents<br />

and brothers.<br />

She learned to play dominos<br />

with her father-in-law and tried<br />

to get to know the servants. In her<br />

mind, she would replay memories <strong>of</strong><br />

happier times – <strong>of</strong> Eid celebrations<br />

at her grandparent’s house, <strong>of</strong> the<br />

rotten lettuce fights she’d have with<br />

her brothers during harvest, or<br />

<strong>of</strong> her dragon-slaying days in the<br />

schoolyard with Sanaa.<br />

A few months later, Nahla<br />

began feeling tired and nauseous.<br />

When she didn’t bleed at her normal<br />

time <strong>of</strong> the month, her mother-in-<br />

She sat down with them.<br />

“Mama, papa…,” she said,<br />

with tears welling in her<br />

eyes. “I want to go home!”<br />

Taken aback, her father<br />

asked: “Why? What is wrong?”<br />

“I haven’t been to school<br />

since the wedding,” lamented Nahla.<br />

“I miss my classes. I miss my friends.”<br />

“Yes dear, we understand.<br />

That is natural,” interjected her<br />

mother. “But this is a new life stage<br />

for you.”<br />

“Fares doesn’t speak to<br />

me,” she continued. “He only seeks<br />

me out when he wants to take me to<br />

the bedroom to have his way with<br />

me. And… he is not gentle. He hurts<br />

me!”<br />

Nahla’s father took a deep<br />

breath and shook his head. Her<br />

mother looked at him, searching for<br />

a reaction, but he seemed at a loss for<br />

words.<br />

She held Nahla by the hand<br />

to comfort her. “I am so sorry.”<br />

Hearing her, Nahla’s father’s<br />

pained expression turned to a scowl<br />

and he sat upright: “Unfortunately,<br />

this is the way things are. You must<br />

obey your husband. Your marriage<br />

was necessary.”<br />

Nahla looked down at the<br />

floor, then up and around their<br />

now-well-stocked kitchen – at the<br />

meat, her mother was preparing on<br />

the counter, at the pitcher <strong>of</strong> fresh<br />

milk on the table. Her family was no<br />

longer struggling to make ends meet.<br />

But why did her happiness have to be<br />

the price?<br />

***<br />

law accompanied her to the doctor’s<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice.<br />

They sat silently in the<br />

waiting room. Far from being like<br />

a ‘mother’ to her, Nahla considered<br />

her more like an overseer, always<br />

barking orders at her, as though she<br />

were one <strong>of</strong> the servants. She never<br />

showed Nahla any love or tenderness<br />

and would turn a blind eye when<br />

Fares yelled at her. And Nahla was<br />

sure she could hear her cries and<br />

screams from the neighboring<br />

bedroom, but she did and said<br />

nothing.<br />

But today her mother-inlaw<br />

looked oddly happy, and even<br />

tried to hold her hand, which Nahla<br />

retracted after feigning a sneeze.<br />

The doctor asked Nahla<br />

several questions before having<br />

her lie down on a large reclining<br />

table. He wheeled over a machine<br />

and placed a cold, jelly-like goo on<br />

her belly then gently ran a rounded<br />

plastic wand over the goo. Suddenly<br />

the sound <strong>of</strong> static came from the<br />

machine – almost like what you<br />

would hear when switching between<br />

radio stations – and then a light<br />

thumping sound.<br />

“There it is!” said the doctor<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

42

PROSE<br />

By JAKAYLA TONEY<br />

said to her mother-in-law. “That is<br />

your grandchild’s heartbeat!”<br />

Nahla’s eyes bulged and she<br />

stopped breathing.<br />

The doctor looked down at<br />

"This [fright] made sense—she<br />

was only 13, petite, and barely<br />

had a woman's body."<br />

her and said: “Congratulations dear.<br />

You are going to be a mother!”<br />

Her look <strong>of</strong> sheer confusion,<br />

followed by panic, made it obvious<br />

that this was not welcome news to<br />

her, so the doctor addressed her<br />

mother-in-law for the rest <strong>of</strong> the<br />

visit.<br />

After he had finished with<br />

the machine and handed Nahla some<br />

paper towels to clean up the goo, he<br />

took her mother-in-law to a corner<br />

<strong>of</strong> his <strong>of</strong>fice and lowered his voice to<br />

a whisper. Nahla tried not to crinkle<br />

the paper so she could overhear and<br />

was able to make out: “there are risks<br />

because she is so young”.<br />

Still trying to process the<br />

idea that there was a baby growing<br />

inside her, the thought that there<br />

could be risks because <strong>of</strong> it frightened<br />

her even more. This made<br />

sense – she was only 13,<br />

petite, and barely had a<br />

woman’s body. She looked<br />

over at her mother-in-law<br />

and the doctor – wishing<br />

she could scream out loud<br />

that she wasn’t ready to be<br />

a mother. Not yet. Not now.<br />

Not with Fares!<br />

She had seen other<br />

young mothers in the neighborhood<br />

and they always looked so forlorn.<br />

Nahla had always imagined it was<br />

because they couldn’t continue with<br />

school. But now she knew it must be<br />

more than that. They’d be stripped <strong>of</strong><br />

their choices in every way.<br />

The thought <strong>of</strong> it all<br />

triggered a deep resistance to what<br />

was happening inside her. Babies<br />

were cute, yes, but she had no clue<br />

how to change diapers or feed a baby<br />

or make them sleep. She had played<br />

dolls, sure. But a real tiny human<br />

that she would be responsible for<br />

was something completely different.<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

43<br />

Now, more than ever, Nahla longed<br />

to be back home playing with dolls<br />

instead or running around in the<br />

fields with her friends, going to<br />

school, and simply enjoying her own<br />

childhood. Not a child raising a child.<br />

Before they left the doctor’s<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice, Nahla’s mother-in-law<br />

hugged her for the first time since<br />

the wedding.<br />

“Nahla, thank you! We are<br />

so thrilled that you are bringing us a<br />

grandchild!”<br />

Lost in thought, Nahla<br />

smiled unconvincingly but said<br />

nothing.<br />

***<br />

Seven months later, Nahla<br />

awakened to intense pain in the<br />

middle <strong>of</strong> the night. Fares ran for his<br />

mother as Nahla lay panting in the<br />

bed. Fares was yelling and looked<br />

frightened. The baby wasn’t expected<br />

for another month.<br />

He carried her<br />

briskly to the car and they arrived at<br />

the hospital within minutes. By that<br />

time, Nahla was crying from the pain.<br />

It is unlike anything she had ever<br />

felt. It was like magnified menstrual<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

PROSE<br />

cramps but with her insides being squeezed out.<br />

The nurses and doctors hurriedly strapped a band around<br />

her arm that inflated and squeezed her. Saying something she couldn’t<br />

understand about her blood pressure, they wheeled her into a closed<br />

room. Something was terribly wrong.<br />

As the pain intensified unbearably, she started screaming.<br />

Overcome by flashes <strong>of</strong> cold, then hot, then terrifying dizziness, Nahla<br />

fainted. Foam began frothing at her mouth as her body started to<br />

stiffen and shake violently.<br />

Once Nahla had stopped seizing, the doctors prepared her for<br />

an emergency c-section to remove the baby. They injected the base<br />

<strong>of</strong> her spine with an epidural to numb her lower body and told her to<br />

look in the other direction while the surgeon began cutting through<br />

the layers <strong>of</strong> skin and muscle beneath her panty line.<br />

The smell <strong>of</strong> blood almost made her vomit and her head<br />

began spinning anew. Nahla lost consciousness again just as the baby<br />

was emerging.<br />

***<br />

When she regained consciousness, the room was quiet and a<br />

doctor was standing nearby speaking to Fares and her mother-in-law.<br />

Relieved that the intensity <strong>of</strong> the pain has passed, and by now anxious<br />

to meet the child she’d been growing inside her all these months,<br />

Nahla searched the room for her baby.<br />

Noticing that she was awake, the doctor came to her bedside.<br />

Speaking in a hushed voice, he said: “Nahla, I’m glad to see you are<br />

back with us. You nearly died.”<br />

Cringing, Nahla closed her eyes and thanked Allah that she<br />

had survived. Then her thoughts quickly turned to her baby.<br />

“And my baby? Is it a boy or a girl?” she asked, expectantly.<br />

The doctor hesitated, looking over at Fares and his mother,<br />

who gave him a nod.<br />

“I’m so sorry but your baby died during the birth. Its oxygen<br />

supply was cut <strong>of</strong>f and….”<br />

After the word ‘died’, Nahla did not register anything<br />

else. The baby she had so dreaded having a few months ago had become<br />

a part <strong>of</strong> her as it had grown in her belly. Although she still resented<br />

her age and lack <strong>of</strong> choice in this pregnancy, she had come to accept it,<br />

even growing excited and imagining what her baby would look like. She<br />

was eager to give it a name and to dress it in the tiny doll-like clothes<br />

she had picked out herself.<br />

“Oh, and it was a girl,” added the doctor, as he left the room.<br />

A girl. Of course. Nahla had always imagined it would be.<br />

A baby girl with curly black hair and big, beautiful brown eyes. She<br />

had secretly wished it would be so, even though she knew her family<br />

wanted a boy. They always did. Surely they wouldn’t be as disappointed<br />

as they would have been, had she lost a boy.<br />

As Nahla stared at her deflated belly, for a fleeting moment, she wished<br />

that she too would have died with her.<br />

***<br />

Nahla decided to name her baby Alya, which means “from<br />

heaven” in Arabic. She held a small ceremony with her parents to bury<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

44<br />

By JESSICA FELICIO

PROSE<br />

her body in the fields near her parents’ home. Fares and<br />

her in-laws had tried to had tried to convince her not to<br />

do so and did not attend. But it was better that way.<br />

As Nahla’s body slowly recovered, her heart also<br />

began healing from the pain <strong>of</strong> losing her daughter. After<br />

watching her lie listlessly in bed for weeks on end, at<br />

the insistence <strong>of</strong> Nahla’s mother, Fares had allowed her<br />

to join a village support group for women who had lost<br />

children and husbands.<br />

The support group helped Nahla grieve and<br />

open up to others about her experience. She even<br />

made friends with another girl, with whom she vented<br />

her frustrations and confided the difficulties she had<br />

at home with the husband she so despised. She also<br />

secretly began taking English language classes after<br />

the support sessions with one <strong>of</strong> the women who was a<br />

teacher. This reignited Nahla’s thirst to return to school<br />

and learn about the world beyond her town.<br />

A few months later, at a follow-up medical<br />

checkup, Nahla’s doctor explained everything that she<br />

had been too distraught to hear that fateful day: that<br />

Nahla was very young, which carried certain health<br />

risks for her and for the baby. He explained that she<br />

had developed a blood pressure condition called<br />

pre-eclampsia that sometimes kills women and girls<br />

during childbirth. She had gone into labor more than a<br />

month early, which was common with young expectant<br />

mothers, but the baby’s organs had not fully developed<br />

yet, and the baby suffered a critical loss <strong>of</strong> oxygen during<br />

her seizure.<br />

With an indifferent expression, the doctor<br />

reassured Nahla that if she waited a few years, the next<br />

time would likely be easier.<br />

Next time? By now, she was 14 and the last thing<br />

she wanted was to go through that experience again!<br />

Nahla sat fuming, her mind flooding with a<br />

thousand ill thoughts that she was not allowed to voice.<br />

She thanked the doctor and left the clinic with her<br />

mother-in-law.<br />

“Do not worry. You will succeed next time.<br />

Perhaps it will even be a boy,” her mother-in-law<br />

reassured her.<br />

The words felt like a punch, deep in her<br />

abdomen. Nahla darted her mother-in-law a stinging<br />

look before getting into the car. But as they pulled out<br />

<strong>of</strong> the parking lot, Nahla realized that her mother-inlaw<br />

was right. If she stayed in this hollow life with Fares,<br />

history would repeat itself. She would be expected to<br />

produce an heir, no matter what the toll on her body or<br />

her happiness.<br />

And it was with this realization that Nahla resolved to<br />

leave – no matter what the consequences.<br />

After a long silence, she asked: “Would you<br />

mind dropping me <strong>of</strong>f at my parents’ house? I need to<br />

talk to them.”<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

45<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

T<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

By GEORGE CHATZHMHTROU<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

46

PROSE<br />

DC Diamondopolous<br />

The Bell<br />

OWER<br />

"Born and raised in Montgomery,<br />

Reverend Penniman had a hard<br />

time staying relevant, what with<br />

tattoos, body piercing, rap music,<br />

not to mention homosexuals<br />

getting married and reefer being<br />

legalized..."<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

47<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

By ALI BERGEN<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G 48<br />

E

PROSE<br />

Reverend<br />

Langston<br />

Penniman sat on the edge<br />

<strong>of</strong> his bed, stretching his<br />

black fingers. Everything<br />

had either twisted up on him or<br />

shrunk except his stomach. Once<br />

six-foot-five, he now plunged<br />

to six two, still tall, but not<br />

the imposing dignitary he<br />

once was standing behind<br />

the lectern in front <strong>of</strong> his<br />

congregation.<br />

His parishioners aged,<br />

too. So hard nowadays to<br />

attract the young, he thought<br />

standing from the bed he<br />

shared with his wife <strong>of</strong> fiftytwo<br />

years. His knees cracked.<br />

He’d gotten his cholesterol<br />

under control, but at seventyfive,<br />

his health headed south<br />

as his age pushed north.<br />

Born and raised in<br />

Montgomery, Reverend<br />

Penniman had a hard time<br />

staying relevant, what with<br />

tattoos, body piercing, By SHANE HOVING<br />

rap music, not to mention<br />

homosexuals getting married<br />

and reefer being legalized.<br />

For a man his age, changing<br />

was like pulling a mule uphill<br />

through molasses.<br />

The smell <strong>of</strong> bacon<br />

and eggs drifted down<br />

the hall. He heard the<br />

c<strong>of</strong>feemaker gurgle. How<br />

he loved his mornings with<br />

the Montgomery Daily<br />

News—not Internet news—<br />

something he could hold in<br />

his hands, smell the ink. He<br />

even enjoyed licking his fingers to<br />

separate the pages.<br />

Off in the direction <strong>of</strong> the Alabama<br />

River, he thought he heard a siren,<br />

not far from his church.<br />

“Breakfast ready,” Flo shouted<br />

from the kitchen.<br />

Flo was the sweetest gift the Lord<br />

ever bestowed upon a man. Oh, he<br />

was fortunate, he thought, passing<br />

her picture on the dresser bureau<br />

and the photo <strong>of</strong> their three boys and<br />

two girls. Proud <strong>of</strong> his church, he was<br />

even prouder <strong>of</strong> their five children.<br />

Three graduated from college, all <strong>of</strong><br />

them respectable citizens.<br />

“It’s gonna get cold if you don’t<br />

‘‘ There's a girl up on the<br />

bell tower <strong>of</strong> your church.<br />

Says she's gonna jump,’’ the<br />

black <strong>of</strong>ficer said.<br />

come and get it.”<br />

“I’m a comin. Just let me wash up.”<br />

The siren sounded closer.<br />

The Alabama spring day was<br />

warmer than usual. At nine in the<br />

morning, it was headed <strong>of</strong>f the<br />

charts, as the kids say nowadays.<br />

Reverend Penniman washed and<br />

dressed. At the bureau, he brushed<br />

back the sides <strong>of</strong> his white hair, his<br />

bald crown parted like the Red Sea.<br />

When his kids teased him about<br />

looking like Uncle Ben, he grew<br />

whiskers just as white. His boys<br />

joked he looked like Uncle Ben with<br />

a beard. He chuckled. He would have<br />

preferred Morgan Freeman.<br />

“I’ll feed it to the garbage<br />

disposal if you don’t come<br />

and get it.”<br />

“I’m a comin now, sweet<br />

thing.”<br />

He heard the siren turn<br />

the corner at Bankhead and<br />

Parks.<br />

Reverend Penniman<br />

looked at the cell phone lying<br />

on his dresser. He’d yet to<br />

master how to get his thick<br />

fingers to press one picture<br />

at a time, or type on that itty<br />

bitty keyboard. He couldn’t<br />

even hold it in the crook <strong>of</strong><br />

his neck.<br />

He hurried down the hall.<br />

The floorboards <strong>of</strong> the fiftyyear-old<br />

house creaked just<br />

like him. Not quite shotgun,<br />

his house did have a similar<br />

layout what with add-ons for<br />

the three boys.<br />

The siren was upon them.<br />

“Lord have mercy,” Flo<br />

said as she put the food on<br />

the table. “That sure sounds<br />

angry.”<br />

“Sure does. Let me take a<br />

look,” the reverend said from<br />

the kitchen’s entrance.<br />

He went to the living room<br />

window and saw a police car<br />

pull into his driveway, the<br />

siren cut-<strong>of</strong>f. Two uniformed<br />

police <strong>of</strong>ficers, one black, the other<br />

white, got out <strong>of</strong> the cruiser and<br />

headed up his footpath.<br />

He opened the door.<br />

“Are you Reverend Penniman?”<br />

“I am. What’s the problem?”<br />

“There’s a girl up on the bell tower<br />

<strong>of</strong> your church. Says she’s gonna<br />

jump,” the black <strong>of</strong>ficer said.<br />

“Good Lord!” Flo cried, standing<br />

behind her husband.<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G<br />

E<br />

49<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM

PROSE<br />

By JONAS JAEKEN<br />

“Let me get my keys,” the reverend<br />

said.<br />

“No time, sir. Come with us. You’ll<br />

get there faster.”<br />

Flo took <strong>of</strong>f and came back with<br />

"Reverend Penniman felt like<br />

he was up on that bell tower,<br />

on the edge, with his arms<br />

stretched out..."<br />

the reverend’s cell phone. “Here<br />

baby. I’m gonna meet you there<br />

soon as I shut down the kitchen. You<br />

should at least have your toast. I can<br />

put it in a baggie for you.”<br />

“No time,” he said as he hurried<br />

out the door with the <strong>of</strong>ficers.<br />

Reverend Penniman sat in<br />

the back <strong>of</strong> the car with a screen<br />

separating him from the policemen.<br />

“Who is she?” he asked.<br />

“Don’t know,” the young white<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer answered.<br />

“What’s she look like?”<br />

“Black teen, skinny, baggy pants,<br />

chain hanging from the pocket,<br />

hoodie pulled over a ball cap.”<br />

“Akeesha.”<br />

“You know her?”<br />

“Like one <strong>of</strong> my own.” The<br />

reverend looked out the<br />

window as the car pulled<br />

away. He clasped his hands<br />

together and said a quick<br />

prayer for the troubled girl.<br />

Lord, help me help her, he<br />

repeated to himself. “Did<br />

she ask for me?”<br />

“No.”<br />

“How’d you find me?”<br />

“Your name is on the<br />

marquee <strong>of</strong> your church.”<br />

“Oh, right.”<br />

“I’m Officer Johnson,” the older<br />

man said. “This is<br />

Officer Perry.”<br />

Officer Perry reached<br />

forward and turned<br />

on the siren. The noise<br />

deafened everything,<br />

including the pounding<br />

<strong>of</strong> Reverend Penniman’s<br />

heart.<br />

They drove toward<br />

downtown Montgomery<br />

along the banks <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Alabama, the RSA tower<br />

soared above the city’s skyline.<br />

The speed limit was forty. The<br />

reverend guessed they were doing<br />

twice that. His right knee pumped<br />

like the needle on Flo’s sewing<br />

machine.<br />

The siren screamed. The lights<br />

blinked and rotated flashing red and<br />

blue on the hood <strong>of</strong> the car. Reverend<br />

Penniman felt like he was up on that<br />

bell tower, on the edge, with his arms<br />

stretched out, his body holding back<br />

the weight <strong>of</strong> all his parishioners<br />

who had wept in his arms.<br />

At the corner <strong>of</strong> Graves and<br />

Buckley, the cruiser slowed, the<br />

siren cut-<strong>of</strong>f. Officer Johnson made<br />

a right turn. People rushed along the<br />

sidewalk their cell phones pressed<br />

By DYNAMIC WANG<br />

THEGLOBALYOUTHREVIEW.COM<br />

P<br />

A<br />

G 50<br />

E

PROSE<br />

By JULIA KADEL<br />

against their ears.<br />

Halfway down the block, Reverend<br />

Penniman saw more people standing<br />

outside his church than he ever had<br />

inside. A fire truck parked in the lot<br />

with men unloading a ladder.<br />

The police car jumped the curb<br />

and drove to the side <strong>of</strong> the brick<br />

building. He saw Greaty, Akeesha’s<br />

great-grandmother in her burgundy<br />

wig, mussed like a tornado whirled<br />

through it. She cupped her black<br />

hands on the sides <strong>of</strong> her mouth<br />

screaming and crying at the ro<strong>of</strong>. Her<br />

pink housecoat hung open revealing<br />

her cotton nightie.<br />

Before the car came to a stop, the<br />

minister jumped out.<br />

Greaty saw Reverend Penniman<br />

and ran to him. “You get my baby <strong>of</strong>f<br />

the ro<strong>of</strong>, you hear, Reverend? She<br />

done gone and have a meltdown.”<br />

“We’ll get her down. Just craving<br />

attention like all teenagers.”<br />

“She cravin’ nothin’ but death. She<br />

gonna jump. She all I have!”<br />

He ran to the front <strong>of</strong> the church.<br />

Greaty followed. The reverend<br />

gasped. “Good Lord.” Akeesha<br />

teetered on the edge <strong>of</strong> the bell’s<br />

shelter. Her baggy pants flapped in<br />

the breeze.<br />

Two firefighters carried a ladder<br />

to the ro<strong>of</strong>. They propped it against<br />

the gutters.<br />

“Get away,” Akeesha screamed.<br />

“I’ll jump, you try to get me.” Her<br />

voice carried over the mob.<br />

“I know the child. I can get her<br />

down.”<br />

“Don’t think so, Reverend.”<br />

The minister turned to see Officer<br />

Johnson standing beside him. “Then<br />

why’d you get me?”<br />

“It’s your church. I thought you’d<br />

be younger.”<br />

“I’m young enough and I’ll get<br />

her down.” He gazed up at the girl.<br />

“Akeesha!” he shouted using his<br />

pulpit voice. “I’m coming to you,<br />

child.” He sprinted around the side<br />

<strong>of</strong> the church, to the back, amazed<br />

at how his body complied with his<br />

will. Officer Johnson’s leather holster<br />

crunched with each matching stride.<br />

Akeesha had broken the frame <strong>of</strong><br />

the door and busted in.<br />

“If I have to cuff you Reverend, I<br />

will,” Officer Johnson said.<br />

“You really want to save this<br />

child?” Reverend Penniman asked.<br />

“I’ve known her since she was four.<br />

I’m the only father she’s ever known.<br />

Now you let me do my business.”<br />

He pushed open the door when he<br />

heard car wheels on gravel.<br />