JEEMS - Rainer Hampp Verlag

JEEMS - Rainer Hampp Verlag

JEEMS - Rainer Hampp Verlag

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

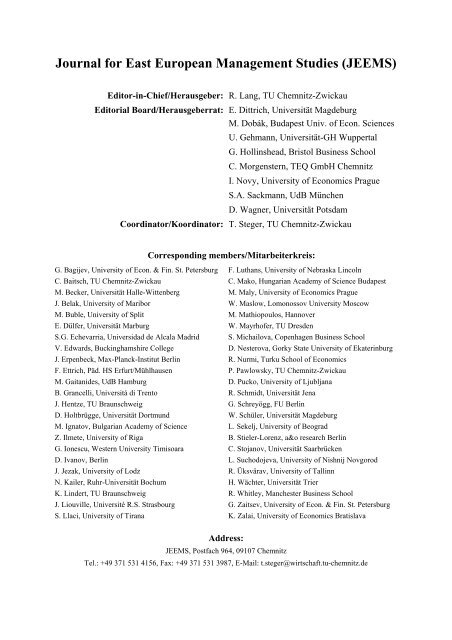

Journal for East European Management Studies (<strong>JEEMS</strong>)<br />

Editor-in-Chief/Herausgeber: R. Lang, TU Chemnitz-Zwickau<br />

Editorial Board/Herausgeberrat: E. Dittrich, Universität Magdeburg<br />

M. Dobák, Budapest Univ. of Econ. Sciences<br />

U. Gehmann, Universität-GH Wuppertal<br />

G. Hollinshead, Bristol Business School<br />

C. Morgenstern, TEQ GmbH Chemnitz<br />

I. Novy, University of Economics Prague<br />

S.A. Sackmann, UdB München<br />

D. Wagner, Universität Potsdam<br />

Coordinator/Koordinator: T. Steger, TU Chemnitz-Zwickau<br />

G. Bagijev, University of Econ. & Fin. St. Petersburg<br />

C. Baitsch, TU Chemnitz-Zwickau<br />

M. Becker, Universität Halle-Wittenberg<br />

J. Belak, University of Maribor<br />

M. Buble, University of Split<br />

E. Dülfer, Universität Marburg<br />

S.G. Echevarria, Universidad de Alcala Madrid<br />

V. Edwards, Buckinghamshire College<br />

J. Erpenbeck, Max-Planck-Institut Berlin<br />

F. Ettrich, Päd. HS Erfurt/Mühlhausen<br />

M. Gaitanides, UdB Hamburg<br />

B. Grancelli, Universitá di Trento<br />

J. Hentze, TU Braunschweig<br />

D. Holtbrügge, Universität Dortmund<br />

M. Ignatov, Bulgarian Academy of Science<br />

Z. Ilmete, University of Riga<br />

G. Ionescu, Western University Timisoara<br />

D. Ivanov, Berlin<br />

J. Jezak, University of Lodz<br />

N. Kailer, Ruhr-Universität Bochum<br />

K. Lindert, TU Braunschweig<br />

J. Liouville, Université R.S. Strasbourg<br />

S. Llaci, University of Tirana<br />

Corresponding members/Mitarbeiterkreis:<br />

F. Luthans, University of Nebraska Lincoln<br />

C. Mako, Hungarian Academy of Science Budapest<br />

M. Maly, University of Economics Prague<br />

W. Maslow, Lomonossov University Moscow<br />

M. Mathiopoulos, Hannover<br />

W. Mayrhofer, TU Dresden<br />

S. Michailova, Copenhagen Business School<br />

D. Nesterova, Gorky State University of Ekaterinburg<br />

R. Nurmi, Turku School of Economics<br />

P. Pawlowsky, TU Chemnitz-Zwickau<br />

D. Pucko, University of Ljubljana<br />

R. Schmidt, Universität Jena<br />

G. Schreyögg, FU Berlin<br />

W. Schüler, Universität Magdeburg<br />

L. Sekelj, University of Beograd<br />

B. Stieler-Lorenz, a&o research Berlin<br />

C. Stojanov, Universität Saarbrücken<br />

L. Suchodojeva, University of Nishnij Novgorod<br />

R. Üksvärav, University of Tallinn<br />

H. Wächter, Universität Trier<br />

R. Whitley, Manchester Business School<br />

G. Zaitsev, University of Econ. & Fin. St. Petersburg<br />

K. Zalai, University of Economics Bratislava<br />

Address:<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong>, Postfach 964, 09107 Chemnitz<br />

Tel.: +49 371 531 4156, Fax: +49 371 531 3987, E-Mail: t.steger@wirtschaft.tu-chemnitz.de

Journal for East European Management Studies (ISSN 0949-6181)<br />

The Journal for East European Management Journal (<strong>JEEMS</strong>) is published four<br />

times a year. The subscription rate is DM 78 for one year (including value<br />

added tax). Subscription for students is reduced and available for DM 39<br />

(including value added tax). The annual delivery charges are DM 6.<br />

Cancellation is only possible six weeks before the end of each year.<br />

The contributions published in <strong>JEEMS</strong> are protected by copyright. No part of<br />

this publication may be translated into other languages, reproduced, stored in a<br />

retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic,<br />

magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise without permission in<br />

writing from the publisher. That includes the use in lectures, radio, TV or other<br />

forms.<br />

Copies are only permitted for personal purposes and use and only from single<br />

contributions or parts of them.<br />

For any copy produced or used in a private corporation serving private purposes<br />

(due to §54(2) UrhG) one is obliged to pay a fee to VG Wort, Abteilung<br />

Wissenschaft, Goethestraße 49, 80336 München, where one can ask for details.<br />

Das Journal for East European Management Studies (<strong>JEEMS</strong>) erscheint 4x im<br />

Jahr. Der jährliche Abonnementpreis beträgt DM 78,- inkl. MWSt.<br />

Abonnements für Studenten sind ermäßigt und kosten DM 39,- inkl. MWSt. Die<br />

Versandkosten betragen DM 6,- pro Jahr. Kündigungsmöglichkeit: 6 Wochen<br />

vor Jahresende.<br />

Die in der Zeitschrift <strong>JEEMS</strong> veröffentlichten Beiträge sind urheberrechtlich geschützt.<br />

Alle Rechte, insbesondere das der Übersetzung in fremde Sprachen,<br />

vorbehalten. Kein Teil darf ohne schriftliche Genehmigung des <strong>Verlag</strong>es in<br />

irgendeiner Form - durch Fotokopie, Mikrofilm oder andere Verfahren -<br />

reproduziert oder in eine von Maschinen, insbesondere von<br />

Datenverarbeitungsanlagen, verwendete Sprache übertragen werden. Auch die<br />

Rechte der Weitergabe durch Vortrag, Funk- und Fernsehsendung, im<br />

Magnettonverfahren oder ähnlichem Wege bleiben vorbehalten. Fotokopien für<br />

den persönlichen und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch dürfen nur von einzelnen<br />

Beiträgen oder Teilen daraus als Einzelkopien hergestellt werden.<br />

Jede im Bereich eines gewerblichen Unternehmens hergestellte oder benützte<br />

Kopie dient gewerblichen Zwecken gemäß § 54(2) UrhG und verpflichtet zur<br />

Gebührenzahlung an die VG Wort, Abteilung Wissenschaft, Goethestraße 49,<br />

80336 München, von der die einzelnen Zahlungsmodalitäten zu erfragen sind.

<strong>JEEMS</strong> • Volume 2 • Number 4 • 1997<br />

Contents<br />

Editorial<br />

Rainhart Lang 357<br />

Articles<br />

Danijel Pucko / Matej Lahovnik<br />

Managers in the transformation process of Eastern Europe - A<br />

case of Slovenia 360<br />

Michel E. Domsch / Uta B. Lieberum / Christiane Strasse<br />

Interkulturelles Personalmanagement in deutsch-polnischen<br />

Joint Ventures und deutschen Tochterunternehmen in Polen 377<br />

Shyqyri Llaci / Vasilika Kume<br />

Woman’s role as owner/manager in the framework of Albanian<br />

business 406<br />

Forum<br />

Frank Heideloff<br />

Differences in socio-cognitive filters - Illustrating an understanding<br />

of the information overload problem in the course of<br />

transformation processes 435<br />

Füzyovà Luba; Miroslava Szarkovà<br />

Two comments on Heideloff 442<br />

Book Reviews<br />

Rainhart Lang<br />

über Janko Belak et al. (Hrsg.): Unternehmensentwicklung und<br />

Management 447<br />

Ingo Winkler<br />

über Christina Weber: Treuhandanstalt - Eine Organisationskultur<br />

entsteht im Zeitraffer 448<br />

News / Information<br />

Kàroly Balaton; Manfred Gardyan 452<br />

Column<br />

Petr Konvicka<br />

Transfer von Management Know-how in den Osten - eine<br />

andere Perspektive 461

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Editorial Mission of <strong>JEEMS</strong><br />

Objectives<br />

The Journal for East European Management Studies (<strong>JEEMS</strong>) is designed to<br />

promote a dialogue between East and West over issues emerging from<br />

management practice, theory and related research in the transforming societies<br />

of Central and Eastern Europe.<br />

It is devoted to the promotion of an exchange of ideas between the academic<br />

community and management. This will contribute towards the development of<br />

management knowledge in Central and East European countries as well as a<br />

more sophisticated understanding of new and unique trends, tendencies and<br />

problems within these countries. Management issues will be defined in their<br />

broadest sense, to include consideration of the steering of the political-economic<br />

process, as well as the management of all types of enterprise, including profitmaking<br />

and non profit-making organisations.<br />

The potential readership comprises academics and practitioners in Central and<br />

Eastern Europe, Western Europe and North America, who are involved or<br />

interested in the management of change in Central and Eastern Europe.<br />

Editorial Policy<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> is a refereed journal which aims to promote the development,<br />

advancement and dissemination of knowledge about management issues in<br />

Central and East European countries. Articles are invited in the areas of<br />

Strategic Management and Business Policy, the Management of Change (to<br />

include cultural change and restructuring), Human Resources Management,<br />

Industrial Relations and related fields. All forms of indigenous enterprise within<br />

Central and Eastern European will be covered, as well as Western Corporations<br />

which are active in this region, through, for example, joint ventures. Reports on<br />

the results of empirical research, or theoretical contributions into recent<br />

developments in these areas will be welcome.<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> will publish articles and papers for discussion on actual research<br />

questions, as well as book reviews, reports on conferences and institutional<br />

developments with respect to management questions in East Germany and<br />

Eastern Europe. In order to promote a real dialogue, papers from East European<br />

contributors will be especially welcomed, and all contributions are subject to<br />

review by a team of Eastern and Western academics.<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> will aim, independently, to enhance management knowledge. It is<br />

anticipated that the dissemination of the journal to Central and Eastern Europe<br />

will be aided through sponsoring.

Editorial<br />

Editorial<br />

Die Rolle der Manager im Transformationsprozeß ist ein Thema, das neben<br />

wissenschaftlicher Erforschung immer auch Gegenstand von Mythen und<br />

Legenden war und ist. Natürlich kann man davon ausgehen, daß in Situationen<br />

umbrechender Strukturen den Führungskräften in den Unternehmen eine<br />

besondere Rolle zukommt, daß Mitarbeiter im Zeichen von<br />

Orientierungslosigkeit Orientierung suchen und entsprechende Erwartungen an<br />

die Führungskräfte richten. Sicher gilt damit auch, daß Führungskräfte in<br />

Transformationsprozessen größere Gestaltungsspielräume haben, als dies in<br />

funktionierenden Systemen der Fall ist. Von Henry Mintzberg stammt der Satz * :<br />

„Great organizations, once created, don‘t need great leaders“. In<br />

Transformationen jedoch entstehen z.T. Betriebe völlig neu, werden<br />

unstrukturiert, grundlegend umgestaltet und reorganisiert. Insofern kann für<br />

diese Zeiten schon gelten „Management does matter“. Andererseits sollten wir<br />

jedoch auch nicht vergessen, daß sowohl die Theorie organisatorischer<br />

Wandlungsprozesse als auch die praktischen Erwartungen die Rolle der<br />

Führungskräfte häufig stark überschätzen. In den Theorieansätzen, ob nun der<br />

Organisationsentwicklung, des organisationalen Lernens, der Organizational<br />

Transformation oder des Business Reengineering, wimmelt es nur so von<br />

Lichtgestalten - Heroen, Helden und Revolutionären -, die die Unternehmen und<br />

die Mitarbeiter durch und aus der Krise führen. Diese Vorstellung findet ihren<br />

Niederschlag auch in der Führungspraxis, wobei darüber hinaus eine solche Art<br />

der Personalisierung auch einen ganz eigenen Zweck verfolgt: im Falle des<br />

Scheiterns ist dann sehr schnell von den „unfähigen“ Führungskräften und<br />

Managern die Rede, die dann auch für Politik- und Systemmängel herhalten<br />

müssen. Veränderungen im Führungsgeschehen selbst sind mithin nicht nur<br />

Produkt des Handelns einzelner Führungskräfte, sondern auch in<br />

Transformationsprozessen, kollektives Werk von verschiedenen<br />

Akteursgruppen, die jeweils auf spezifische strukturelle Muster, Ressourcen und<br />

Regeln zurückgreifen und diese in den Wandlungsprozeß einbringen können.<br />

Die hier kurz skizzierte Problematik kennzeichnete auch die Beiträge und<br />

Diskussionen auf dem III. Chemnitzer Ostforum in diesem Frühjahr. Die<br />

folgenden Artikel beschäftigen sich mit Führungskräften und<br />

Führungskräfteverhalten in den Wandlungsprozessen in Mittel- und Osteuropa.<br />

Danijel Pucko und Matej Lahovnik analysieren die Rolle der Manager im<br />

slowenischen Transformationsprozeß und gehen dabei insbesondere auf die<br />

unterschiedlichen Wert- und Zielsysteme slowenischer Manager und ihrer<br />

westeuropäischen Partner ein. Michel Domsch, Uta Lieberum und Christiane<br />

* Mintzberg, H.: Musings on Management. Havard Business Review. July/ August 1996, p.<br />

64.<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 357

Editorial<br />

Strasse betrachten in einem weiteren Beitrag zum Chemnitzer Ostforum Ansätze<br />

für ein interkulturelles Personalmanagement in deutsch-polnischen Joint<br />

Ventures und deutschen Tochterunternehmen in Polen.<br />

Sie arbeiten dabei vor allem kulturelle und mentale Unterschiede zwischen<br />

polnischen und deutschen Führungskräften und die sich daraus ergebenden<br />

Konsequenzen für die Übertragung von Unternehmenskulturen und<br />

vorbereitende Personalentwicklungsmaßnahmen heraus. Shyqyri Llaci und<br />

Vasilika Kume schließlich beschäftigen sich in ihrem Beitrag mit der Rolle der<br />

Frauen als Eigentümer und Manager in albanischen Unternehmen. Sie zeigen<br />

dabei, daß es im Transformationsprozeß unter den besonders schwierigen<br />

albanischen Bedingungen vor allem für weibliche Manager einen erschwerten<br />

Zugang zu Wissen und Fähigkeiten auf dem Gebiet des Managements gibt.<br />

Im Forum findet sich ein interessanter Beitrag von Frank Heideloff über<br />

unterschiedliche sozio-kognitive Filter, die zu einen differenzierten Umgang mit<br />

dem „Information overload“ in slowakischen Transformationsbetrieben führen.<br />

Rezensionen zu Büchern über Managementprobleme im<br />

Transformationsprozeß, News sowie eine kritische Kolumne zum Transfer von<br />

Management know how in den Osten von Petr Konvicka runden diese Ausgabe<br />

von <strong>JEEMS</strong> ab.<br />

Rainhart Lang<br />

358<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Neues Mitglied des Editorial Board<br />

Editorial<br />

Für den aus privaten Gründen ausscheidenden Prof. Ivanov wurde Prof.<br />

Morgenstern neues Mitglied des Editorial Board von <strong>JEEMS</strong>.<br />

Prof.Dr.-Ing.habil. Claus Morgenstern, geb. 1947, studierte Technologie des<br />

elektronischen Gerätebaus an der Ingenieurhochschule Mittweida. 1976<br />

promovierte er auf dem Gebiet der Analyse, Modellierung und Optimierung<br />

technologischer Prozesse. Von 1979 bis 1982 leitete er die Abteilung Forschung<br />

und Entwicklung im VEB NARVA Brand-Erbisdorf. Danach arbeitete er 6<br />

Monate am Leningrader Elektrotechnischen Institut. Anschließend ging er<br />

zurück an die Ingenieurhochschule Mittweida. 1985 habilitierte er sich an der<br />

Technischen Universität Dresden. Professor Morgenstern hielt in Bulgarien und<br />

Polen Gastvorlesungen und wurde 1989 zum ordentlichen Professor für<br />

Prozeßtechnologie/Qualitätssicherung an die Ingenieurhochschule Mittweida<br />

berufen. Von 1990 bis 1992 war er dort Direktor der Sektion Technologie des<br />

elektronischen Gerätebaus. Seit 1992 ist er geschäftsführender Gesellschafter<br />

und Leiter des Instituts für Qualitätsmanagement und Fertigungsmeßtechnik der<br />

TEQ GmbH. Professor Morgenstern ist anerkannter Dozent der DGQ und der<br />

Akademie für Führungskräfte der Wirtschaft in Bad Harzburg. Weiterhin ist er<br />

anerkannter Dozent und Unternehmensberater des RKW und Mitglied der<br />

Forschungsgemeinschaft Qualitätssicherung e.V.<br />

Die TEQ GmbH ist deutschlandweit und international, z.B. in Polen, Bulgarien,<br />

Rußland und Estland, auf den Gebieten Qualitäts- und Umweltmanagement<br />

sowie Unternehmensführung tätig. Geschäftsbereiche der TEQ GmbH sind:<br />

Unternehmensberatung (ISO 9000, Total Quality Management TQM,<br />

Umweltmanagement)<br />

Bildung (QM-Systeme, Umweltmanagement, Unternehmensführung)<br />

Forschung/Entwicklung (Methoden für die kontinuierliche<br />

Qualitätsverbesserung, Analyse, Modellierung und Optimierung von<br />

Prozessen)<br />

Meßtechnische Dienstleistungen<br />

An die TEQ GmbH angegliedert ist das Institut für Qualitätsmanagement und<br />

Fertigungsmeßtechnik. Zur TEQ-Gruppe gehören drei Tochterfirmen, davon<br />

eine in Zielona Gora/Polen.<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 359

Managers in the transformation process of Eastern Europe<br />

Managers in the transformation process of Eastern<br />

Europe - A case of Slovenia *<br />

Danijel Pucko / Matej Lahovnik **<br />

The article offers results of the empirical research project on strategic<br />

restructuring processes in Slovenian enterprises. The changes in the positions<br />

of managing directors of enterprises and developments of the value systems and<br />

objectives of Slovenian managers are discussed. The authors show a<br />

comparison of the relevant values and objectives of Slovene managers and their<br />

Western European counterparts. They briefly describe the differencies between<br />

both groups of managers. The research has tried to identify the managing<br />

directors' perception of the competitive advantage's factors and the business<br />

strategies that are being implemented in the Slovenian enterprises. Finally, the<br />

managing directors' assessments of the length of the strategic restructuring<br />

process in the Slovenian "old" firms are presented.<br />

Der Artikel handelt von den Änderungen in den Führungspositionen der<br />

"ehemaligen" slowenischen Firmen, der Entwicklung des Bewertungssystems<br />

und den Zielen der slowenischen Geschäftsführer. Es folgt eine<br />

Gegenüberstellung der relevanten Bewertungen und Ziele zwischen den<br />

slowenischen und westeuropäischen Geschäftsführern, wobei die Unterschiede<br />

zwischen den beiden Geschäftsführergruppen aufgezeigt werden. Weiter wird<br />

ein Vergleich gezogen zwischen den Konkurrenzfaktoren, die als das wichtigste<br />

Element des strategischen Handelns bezeichnet werden können. Außerdem<br />

werden die Geschäftsstrategien beschrieben, die in den slowenischen Firmen<br />

umgesetzt worden sind. Abschließend wird eine Prognose über die Dauer der<br />

strategischen Umstrukturierungsprozesse abgegeben.<br />

* Manuscript received: 24.4.97, accepted: 19.9.97<br />

** Danijel Pucko , born 1944, PhD., Professor at the Faculty of Economics, University of<br />

Ljubljana. His main professional field of interest is Strategic Management, Business<br />

Planning and Business Economics.<br />

Mail address: University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Economics, Kardeljeva ploscad 17, 1000<br />

Ljubljana, Slovenia<br />

Email: daniel.pucko@uni-lj.si<br />

360<br />

Matej Lahovnik, born 1971, Assistant teacher at the Faculty of Economics, University of<br />

Ljubljana.<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

1. Introduction<br />

Danijel Pucko / Matej Lahovnik<br />

Slovenia established a democratic political system in 1990. It became a new,<br />

independent European state in 1991 when the Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia<br />

split apart. Slovenian businesses lost a relatively huge domestic market as a<br />

result of all these changes. It could be argued that the country has been in<br />

transition since 1990. Political and economic reforms have been present in the<br />

country since the time when new political parties seized power in Spring, since<br />

1990. The transition in Slovenia has been going on for six years. The<br />

privatisation process of former "social" enterprises (self-managing business<br />

firms) started to be implemented in 1994. The great majority of "social"<br />

enterprises have already been privatised.<br />

The majority of enterprises that already existed before the transition period have<br />

been forced to strategically restructure themselves because of radical changes<br />

which have taken place in their environment. In more than two thirds of the<br />

enterprises the restructuring processes are not completed yet. These processes<br />

are lead by managing directors of businesses and by top management teams.<br />

The analysis is to focus on six key issues: firstly the changes which have taken<br />

place in the positions of the managing directors of enterprises; secondly, the<br />

developments which have taken place in the value systems of managing<br />

directors and senior managers; thirdly the personal objectives of these<br />

executives, and fourthly, their objectives as employers. The values and<br />

objectives of the Slovenian managers are compared with those of Western<br />

European managers. As values and personal objectives influence enterprises'<br />

strategic objectives and the managing directors' perception of the competitive<br />

advantage's factors, we intend to identify the stated variables and offer some<br />

relevant empirical findings. As business units try to achieve their competitive<br />

advantages through the use of business strategy, business strategies of the<br />

Slovenian enterprises are presented. Finally, we asked the Slovenian managers<br />

to analyze the current situation and to predict the length of the process of<br />

strategic restructuring in Slovenian enterprises.<br />

On the one hand our research was based on the theoretical examination of the<br />

managers' position in the transformation process (Kilmann et al., 1988) and<br />

phenomenon of strategic restructuring of an enterprise (Brilmann, 1986) and on<br />

the other hand on an extensive questionnaire. Managing directors or members of<br />

the management teams of Slovenian enterprises were asked to respond to the<br />

questions in the questionnaire. The empirical research was limited to five<br />

strongest manufacturing industries (metal and metal products, electrical and<br />

optical equipment, chemical, textile and garment, and food processing) in<br />

Slovenia, which were selected according to their shares in the creation of GNP<br />

in 1990. We excluded small enterprises from our sample ( i.e. enterprises with<br />

less than 125 employees). All the enterprises included in the sample had to meet<br />

one requirement, which was, that they had been founded before 1990. New<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 361

Managers in the transformation process of Eastern Europe<br />

enterprises, which were founded during the transition period, were of no<br />

research interest to us. Our assumption was that only old enterprises needed<br />

strategic restructuring.<br />

In the 1994 survey 64 enterprises out of 250, which existed in the mentioned<br />

five industries and which met the requirement, responded (Pucko, 1995, No.5-<br />

6). The 1996 survey was based on the same criteria. Some undergraduate and<br />

graduate students of the Faculty of Economics in Ljubljana collected answers to<br />

our questionnaire from 80 enterprises.<br />

Out of 80 enterprises, which co-operated in the research, 59.5% are<br />

incorporated, 34.2% are limited companies, the rest has some other legal status.<br />

The majority of responding enterprises has a mixed ownership (38%), 31.6%<br />

enterprises are privately owned, and 26.6% are still social companies (selfmanaging<br />

firms). The rest is owned by the Development Fund of the Republic<br />

of Slovenia or by the state.<br />

2. Managing directors as leaders of strategic restructuring of<br />

enterprises<br />

The research results show that 51.3% of all managing directors have held their<br />

positions from the eighties. One quarter of managing directors (25.6%) took<br />

over their positions in the 1990-1991 period. About a quarter of managing<br />

directors (23.1%) have got these positions in the last three years. The stated<br />

shares support the thesis that there have been no major politically motivated<br />

changes at the level of managing directors in firms. It is quite logical (Kilmann<br />

et al., 1988) that many more new managing directors have been nominated to<br />

their positions in those enterprises that have met with some type of crisis than in<br />

those enterprises that have not experienced serious economic difficulties in the<br />

transition period. (See Table 1.) As the number of responses to that particular<br />

question was higher in the 1994 research, and as there are significant differences<br />

in findings, the results of the larger sample (e.g. from 1994) should be more<br />

reliable.<br />

Age distribution of managing directors could not be assessed as a bad one. 7.7%<br />

of managing directors are younger than 36. Most managing directors belong to<br />

the age bracket between 46 and 55 years (53.8%), which is certainly an age that<br />

still allows for creativity and serious contributions to company development.<br />

Their life working time horizon is still long enough that they are motivated to<br />

create vision for their company and to take over needed business risk in<br />

implementing it. 28.2% of managing directors are in the age bracket between 36<br />

and 45 years. They are still young, but usually well educated. Modest<br />

management education and experience might be a possible weakness for the<br />

majority of Slovenian managers. Of course, our conclusions should not be too<br />

362<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Danijel Pucko / Matej Lahovnik<br />

firm as we have not been researched into the Slovenian top management talents<br />

and skills.<br />

Table 1: How long does a managing director hold his/her position in a<br />

company according to the 1994 and 1996 researches<br />

Period<br />

Company<br />

performance<br />

Research in 1994 Research in 1996<br />

Managing<br />

director<br />

holding his<br />

position<br />

already<br />

before 1990<br />

A new<br />

managing<br />

director in<br />

the period of<br />

transition<br />

Total Managing<br />

director<br />

holding his<br />

position<br />

already before<br />

1990<br />

A new<br />

managing<br />

director in<br />

the period<br />

of<br />

transition<br />

Good 15 17 32 16 13 29<br />

Not good 5 21 26 4 6 10<br />

Total:<br />

Number<br />

%<br />

20<br />

34.5<br />

38<br />

65.5<br />

58<br />

100.0<br />

How do managing directors perceive their key tasks within the processes of<br />

strategic restructuring of their enterprises? Most managing directors consider<br />

that over the period of the next three years their most important tasks will be<br />

linked to cost reduction (32.5%), search for new markets (32.5%), introduction<br />

of total quality concepts into their firms (30%), and many others. (See Table 2.)<br />

Comparing the perception of the key tasks as found in the 1994 research with<br />

the stated one, some significant differences could be noticed. Nowadays there<br />

are many more enterprises that have a very well defined strategy, more or less<br />

settled personnel issues (managerial and staff), clear plans regarding their future<br />

development with regard to the product range (Goold, 1996), and have already<br />

implemented the needed organisational changes. Therefore, it seems that their<br />

key tasks (let us assume that we deal with the second stage in the process of<br />

strategic restructuring of enterprises within the framework of transition) are<br />

becoming linked to cost reduction, quality, and market development.<br />

Key tasks should have some connection with the most difficult problems, which<br />

managing directors have to solve. Let us find out, therefore, which have been<br />

those problems according to the managing directors' perceptions in the last three<br />

years. Privatisation (27.5% of managing directors), finding substitute sales<br />

markets (22.5%), cost reduction (21.3%), enterprise reorganisation (21.3%),<br />

reduction of labour force (21.3%), financial consolidation of enterprise (18.8%),<br />

and restructuring company product range (16.3%) are identified as the toughest<br />

problems that managing directors have dealt with in the second phase (1994 -<br />

1996) of the transition process in Slovenia. Comparing those problems with the<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 363<br />

20<br />

51.2<br />

19<br />

48.8<br />

Total<br />

39<br />

100.0

Managers in the transformation process of Eastern Europe<br />

ones that were most frequently mentioned in the 1994 research, we may argue<br />

that in the first phase of the transition process the problems of appropriate<br />

human resources, labour force reduction, and product range restructuring were<br />

far more pronounced than in the last three years.<br />

Table 2: Managing director's key tasks in the strategic management process in<br />

the next three years<br />

Managing director's key tasks % of managing directors according<br />

to the 1994 research<br />

Formulating a new strategy<br />

Recruitment and develop-<br />

ment of personnel<br />

Product development<br />

Market development<br />

Organisational changes<br />

Privatisation<br />

Cost reduction<br />

Team building<br />

Quality<br />

Strategy implementation and<br />

follow - up<br />

364<br />

34.4<br />

28.1<br />

21.9<br />

21.9<br />

21.9<br />

20.3<br />

20.3<br />

12.5<br />

10.9<br />

10.9<br />

% of managing directors according<br />

to the 1996 research<br />

3. Personal values and attitudes held by the Slovenian top<br />

managers<br />

The managing directors' values have been changing slowly and insignificantly<br />

in the transition period (See Table 3 and 6). They still differ noticeably from the<br />

value systems of Western European entrepreneurs and managers. Comparison<br />

with the research results of the STRATOS joint research project (The<br />

STRATOS Group, 1990: 27 and 36) proves this fact.<br />

The most important personal value held by the Slovenian top managers is<br />

obviously the statement that "a firm should enter foreign markets". Western<br />

European managers in small countries assigned only 3.74 mean-weighted score<br />

to this value. The reason for such result is that Slovenian firms have a relatively<br />

small domestic market nowadays. In the past Slovenian economy achieved<br />

24.8% of its total sales on the markets of former Yugoslavia. The share of total<br />

sales to Eastern European markets was lower than 5% compared to 17.9% on<br />

the hard currency markets (Regionalna struktura,1991). Radical changes on the<br />

17.5<br />

18.8<br />

14.0<br />

32.5<br />

10.0<br />

...<br />

32.5<br />

...<br />

30.0<br />

...<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Danijel Pucko / Matej Lahovnik<br />

domestic and Eastern European markets forced Slovenian enterprises into<br />

restructuring their sales markets. At first this task seemed nearly unattainable, at<br />

least in the short run. Enterprises were first implementing the restructuring of<br />

their sales market by strengthening their sales on the small Slovenian market<br />

(i.e. new domestic market). Later those firms, which enjoyed the biggest shares<br />

of sales on the Slovenian market, gradually started to acquire substitute markets.<br />

(See Table 4.) They have reached some apparent achievements in this field.<br />

Table 3: The most important personal values and attitudes held by the<br />

Slovenian top managers<br />

A firm should enter foreign markets<br />

Value or attitude Mean weighted score<br />

Managers even at the highest level should regularly take part in training<br />

programmes<br />

Managers should strive for profit maximisation<br />

Managers should consider ethical principles in his behaviour<br />

When in doubt the manager should seek further information rather than make<br />

an immediate decision<br />

Managers should establish their authority<br />

Managers should be more concerned about the future of a firm than about the<br />

present<br />

Attitudes to employees should be based on the belief that satisfied employees<br />

are always good employees<br />

A firm should try to hold the largest market share and to become the market<br />

leader<br />

The policy of a business should be a matter for the management and for<br />

employees<br />

4.63 (1)<br />

4.39 (2)<br />

4.35 (3)<br />

4.30 (4)<br />

4.19 (5)<br />

4.10 (9)<br />

4.09 (6)<br />

4.04 (7)<br />

3.96 (10)<br />

3.81 (8)<br />

Notes: 1) A five point scale was used in the assessment: 1 = I strongly disagree, 5 = I<br />

strongly agree<br />

2) In the brackets there are ranks assigned to an individual value or attitude in the<br />

1994 research<br />

96.3% of enterprises from the sample have some export sales today. A vast<br />

majority (84.2%) of enterprises have at least 7 and more years of experience in<br />

the field of exporting. 55.4% of enterprises created more than one half of their<br />

turnover by exporting in 1995, 54.8% in 1994, and 66.0% in 1993. It seems that<br />

there has been some shift away from the implementation of an export expansion<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 365

Managers in the transformation process of Eastern Europe<br />

strategy after 1993 among Slovenian enterprises. This change in the strategic<br />

behaviour could be the result of the exchange rate policy on the one hand, and<br />

of the dynamic growth of domestic consumption and other influential external<br />

strategic factors on the other.<br />

Table 4: Shares of sales on domestic market in 1990, 1993, and 1995<br />

Sales share Year 1990* Year 1993 Year 1995<br />

up to 10%<br />

above 10-30%<br />

above 30-50%<br />

above 50-70%<br />

above 70-90%<br />

above 90%<br />

366<br />

3.4<br />

13.6<br />

15.3<br />

20.3<br />

30.5<br />

16.9<br />

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0<br />

* Results of the research implemented in 1994<br />

"A strive for profit maximization" is also a very significant value (See Table 3).<br />

Slovenian managers place much more emphasis on profit maximization than<br />

their western counterparts. We can see this from the export sales profit margin<br />

reached by Slovenian enterprises. It can be concluded that the restructuring of<br />

the sales markets of Slovenian firms has diminished their sales profit margins.<br />

Enterprises have not been able to improve the levels of these margins after<br />

1993, on the contrary they have been confronted with some further slight<br />

change for the worse. (See Table 5.) Unfavourable factors in the macro<br />

environment and stagnation of strategic restructuring of enterprises could be<br />

possible reasons for these results.<br />

Table 5: Profit margin, achieved on foreign (hard currency) markets in 1990,<br />

1993, and 1995<br />

Level of the profit<br />

margin<br />

no profit margin<br />

minimal margin<br />

modest margin<br />

good margin<br />

unknown<br />

11.1<br />

31.9<br />

27.8<br />

15.3<br />

9.7<br />

4.2<br />

13.9<br />

33.3<br />

23.6<br />

20.8<br />

Year 1990* Year 1993* Year 1995<br />

12.2<br />

15.1<br />

24.2<br />

45.5<br />

3.0<br />

24.6<br />

33.3<br />

42.1<br />

-<br />

-<br />

5.6<br />

2.8<br />

37.6<br />

24.7<br />

32.5<br />

5.2<br />

-<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Danijel Pucko / Matej Lahovnik<br />

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0<br />

* Results of the research, implemented in 1994<br />

In spite of this fact Slovenian enterprises have been implementing the strategy<br />

of entering new foreign markets (72.5% of enterprises) and of sales increase on<br />

foreign markets (71.3% of enterprises). The strategy of sales enlargement on<br />

domestic market is only the third most usually implemented one (51.3% of<br />

enterprises).<br />

The results of STRATOS group show that managers in smaller countries are<br />

likely to avoid change (mean weighted score 2.19) and that managers in larger<br />

countries tend to be more open to change than those in smaller countries.<br />

Managers in larger countries are more interested in cooperation. They even want<br />

to co-operate with very large companies and grow even in foreign markets (The<br />

STRATOS Group, 1990, p.31).<br />

We could not find any empirical evidence in the case of Slovenia for such<br />

conclusions. On the contrary, our empirical results show many differences in<br />

personal values and attitudes of Slovenian managers when compared with the<br />

value orientation of Western European managers. Slovenian managers are more<br />

open to changes than their Western European counterparts. They have been<br />

exposed to many turbulent changes in the process of transition and they deal<br />

with changes as with any usual procedure. They assigned to the value " Changes<br />

in a business should be avoided at all costs" the lowest rank which is even<br />

below the score of the Western European managers (See Table 6).<br />

They are also more prepared to use different forms of subcontracting activities.<br />

Western European managers in small countries assigned mean-weighted score<br />

3.17 to the value "Firms should co-operate with other firms to be effective even<br />

at the expense of some independence" (The STRATOS Group, 1990, p.31). In<br />

our 1994 research (Pucko, 1995, No.1-2: 27) we came to an important<br />

conclusion, namely, that many Slovenian enterprises applied some kind of a<br />

subcontracting strategy during the first three years of transition. In the 1991 -<br />

1993 period 39.6% of enterprises started to build subcontracting relationships.<br />

In the last three year period 27.5% of firms have started some new<br />

subcontracting (most, i.e. 81,8% of them, with foreign partners). On the other<br />

hand, only 5% of firms abandoned such relationships during the same period.<br />

28.8% of Slovenian subcontractors increased the number of their partners. 30%<br />

of them increased the number of products that were the objects of their<br />

subcontracting relationships. Only 17.5% of enterprises reduced the number of<br />

customers in their subcontracting relationships. A relatively small number of<br />

firms (12.5%) diminished the number of products under the subcontracting<br />

terms.<br />

In fact Stratos research shows that 41.4 % of firms in Western European<br />

countries (those which were included in the research) use some form of<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 367

Managers in the transformation process of Eastern Europe<br />

subcontracting activities. The Stratos research confirms the opinion that larger<br />

countries , and the markets associated with them, offer more favourable<br />

conditions for subcontracting compared with smaller countries.<br />

Table 6: The less acceptable personal values and attitudes held by top Slovene<br />

managers<br />

368<br />

Value or attitude Mean weighted score<br />

Changes in a business should be avoided at all costs 1.69 (1)<br />

Management is man' s work 1.74 (3)<br />

The manager should co-ordinate all tasks and activities himself 1.96 (4)<br />

Innovation involves too much risk 2.01 (7)<br />

Firms should only introduce proven office procedures and<br />

production techniques<br />

2.03 (9)<br />

Managers should criticise poor work by employees before their colleagues 2.10 (16)<br />

Managers should only rely on their intuition when making decisions 2.13 (2)<br />

A firm should start from the principle of equal pay for equal work even<br />

if this raises costs<br />

2.14 (13-14)<br />

A firm should plan in detail even at the risk of losing flexibility 2.15 (6)<br />

Notes: 1) A five point scale was used in the assessment: 1 = I strongly disagree, 5 = I<br />

strongly agree<br />

2) In the brackets there are ranks assigned to an individual value or attitude in the<br />

1994 research<br />

We have established that 44.9% of Slovenian firms are implementing some sort<br />

of a subcontracting strategy nowadays. Three thirds of them create more than<br />

20% of their total turnover by subcontracting. Nearly one quarter of enterprises<br />

create more than one half of their total sales by subcontracting. All these<br />

findings show that subcontracting strategies have been extraordinary important<br />

kinds of strategy for Slovenian business firms after Slovenia was established as<br />

an independent state. This strategic orientation of Slovenian enterprises has<br />

been apparently chosen as a way of integrating Slovenian manufacturing firms<br />

into the European economy.<br />

4. Objectives of top managers and of the Slovenian enterprises<br />

The personal objectives of the managing directors of Slovenian "old"<br />

enterprises appear to match quite well with the personal objectives of the<br />

Western European entrepreneurs and managers. On the other hand, some slight<br />

changes to the personal objectives of top Slovene management, during the early<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Danijel Pucko / Matej Lahovnik<br />

stage of transition (first 3 years) and during the second stage (the last two years)<br />

may be identified (See Table 7).<br />

Western European managers appreciate least "high social status" (2.14) and<br />

"playing a role in society" (2.49). Respondents in Western Europe attach very<br />

little importance to everything that is primarily society oriented (The STRATOS<br />

Group, 1990, p.52). On the basis of our empirical findings the same could be<br />

concluded for the Slovenian managers.<br />

Table 7: The individual objectives of top managers, ranke by importance<br />

Rank Individual objective Mean weighted<br />

score<br />

(Slovenia)<br />

Mean weighted<br />

score<br />

(Stratos)<br />

1 Making good products 4.64 (1) 4.52 (1)<br />

2 Job satisfaction 4.56 (2) 4.29 (2)<br />

3 Financial independence for you and your family 4.09 (3) 4.02 (4)<br />

4 Doing better than other businessmen 4.06 (5) 3.15 (8)<br />

5 Selfactualisation 3.88 (4) 3.97 (5)<br />

6 High level of income 3.78 (6) 3.15 (7)<br />

7 Meeting people 3.73 (7) 3.85 (6)<br />

8 Influence 3.48 (9) 2.71 (11)<br />

9 Personal independence 3.41 (8) 4.08 (3)<br />

10 High social status 3.26 10) 2.14 (14)<br />

11 Attractive life-style 3.15 (11) 2.80 (10)<br />

12 Playing a role in society 3.15 (12) 2.49 (12)<br />

Note: 1) A five points scale was used in the assessment: 1 = no importance 5 = very high<br />

importance<br />

2) In the brackets of Slovenian research there are ranks assigned to an individual<br />

value or attitude in the 1994 research<br />

3) In the brackets in Stratos research there are ranks assigned to an individual value or<br />

attitude according to the Stratos research.<br />

The top Slovenian managers consider their objectives as employers (See Table<br />

8) in almost the same way as their Western European counterparts (Compare<br />

with the STRATOS Group results). Both groups of businessmen evaluate as the<br />

most important the first four objectives stated in Table 8. They even assigned<br />

similar mean-weighted scores to them. The top Slovenian managers considered<br />

the last four ranked objectives in the Table 5 to be much more important than<br />

their Western European counterparts did.<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 369

Managers in the transformation process of Eastern Europe<br />

The objectives of Slovenian businesses appear to be pretty stable during the<br />

transition period. They are quite similar to the most important objectives of<br />

Western European business firms. Among the ten most important objectives<br />

eight of them are equal. Both groups of managers consider quality as the most<br />

important strategic objective and that certainly reflects the current world's trend.<br />

Slovenian managers emphasized the necessity of cost reduction more than<br />

Western European managers did what is no doubt related to the strategic<br />

restructuring process of the Slovenian economy.<br />

Table 8: The top managers' objectives as employers<br />

Good working conditions<br />

Saving jobs<br />

Self-fulfilment<br />

Improving my employees' life style<br />

Profit sharing<br />

370<br />

Objective Mean weighted score<br />

(Slovenia)<br />

Participation of employees in ownership<br />

Job creation<br />

Participation of employees in decision-making<br />

4.19 (1)<br />

3.98 (2)<br />

3.86 (5)<br />

3.83 (4)<br />

3.47 (3)<br />

3.41 (7)<br />

3.30 (6)<br />

3.11 (8)<br />

Mean weighted score<br />

(Stratos)<br />

4.01 (1)<br />

3.82 (2)<br />

3.69 (3)<br />

3.42 (4)<br />

2.39 (7)<br />

2.96 (6)<br />

2.98 (5)<br />

1.78 (8)<br />

Note: 1) A five point scale was used in the assessment: 1 = no importance, 5 = very high<br />

importance<br />

2) In the brackets there are ranks assigned to an individual value or attitude in the<br />

1994 research<br />

3) In the brackets in Stratos reesearch there are ranks assigned to an individual value<br />

or attitude according to the Stratos research.<br />

5. Business strategies of Slovenian enterprises<br />

The essence of a business strategy is linked to the definition of how a strategic<br />

business unit can achieve its competitive advantage (Porter, 1985: 11). There<br />

could be many strategic factors for achieving a competitive advantage. Let us<br />

look into the factors that are considered to be the most important for providing a<br />

competitive advantage for strategic product groups of Slovenian enterprises on<br />

their main market! Managing directors or top management assessed the<br />

importance of 26 factors by assigning to each of them different weights (1= no<br />

importance, 2= little importance, 3= medium importance, 4= great importance,<br />

and 5= very great importance). If we multiply the number of assessments of<br />

each category with the appropriate weight, we are able to compute the average<br />

weighted assessment for each factor. This average weighted assessment enables<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Danijel Pucko / Matej Lahovnik<br />

us to identify the most important factors, which determine a competitive<br />

advantage. Those factors have been computed for Slovenian enterprises and are<br />

shown in Table 10.<br />

Table 9: The most important strategic objectives of the Slovenian "old" business<br />

firms in the 1996 and Western European enterprises<br />

1. Product quality<br />

2. Cost reduction<br />

3. Good liquidity<br />

4. Productivity<br />

5. Profit<br />

6-7. Creativity and innovations<br />

6-7. Flexibility<br />

8. Financial independence<br />

9. Market share<br />

10. Economic authonomy<br />

11. Company image<br />

12. Growth<br />

Objective Mean weighted score<br />

(Slovenia)<br />

4.84 (1)<br />

4.65 (2)<br />

4.56 (4)<br />

4.54 (3)<br />

4.48 (5)<br />

4.40 (7)<br />

4.40 (8)<br />

4.28 (6)<br />

4.25 (9)<br />

4.17 (12)<br />

4.15 (10)<br />

4.06 (11)<br />

Mean weighted score<br />

(Stratos)<br />

4.48 (1)<br />

4.06 (9)<br />

4.31 (3)<br />

4.21 (4)<br />

4.04 (10)<br />

4.12 (7)<br />

4.18 (5)<br />

4.13 (6)<br />

3.66 (12)<br />

3.81 (11)<br />

4.07 (8)<br />

3.60 (13)<br />

Note: 1) A five point scale was used in the assessment: 1 = no importance, 5 = very high<br />

importance<br />

2) In the brackets there are ranks assigned to an individual value or attitude in the<br />

1994 research<br />

3) In the brackets in Stratos research there are ranks assigned to an individual value<br />

or attitude according to the Stratos research.<br />

Links between the Slovenian firms' objectives and the top managers' personal<br />

objectives on one hand and, on the other hand, links between them and the top<br />

managers' ranking of the factors of the competitive advantage apparently exist,<br />

too (see Table 10). The roots of competitive advantages in Slovenia are,<br />

according to both research projects, quite similar to those in Western European<br />

countries. Slovenian managers attribute more importance to low costs and less<br />

importance to firm's reputation than their Western European counterparts but<br />

otherwise we may identify many similarities.<br />

Most Slovenian enterprises implement a niche strategy (53%) on their market.<br />

One quarter of firms apply a product differentiation strategy. The cost<br />

leadership strategy is implemented by one fifth of Slovenian firms. As niche<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 371

Managers in the transformation process of Eastern Europe<br />

strategies can be theoretically directed on product differentiation or low cost, we<br />

should find out how these two strategic options are applied in Slovenian firms.<br />

Table 10: Most important factors determining competitive advantage of<br />

enterprises<br />

1. Product quality<br />

2. Reliability of supply<br />

3. Low costs<br />

4. Management quality<br />

5. Flexibility<br />

6. Skills<br />

7. Trademark<br />

8. Firm's reputation<br />

9. Creativity<br />

10 - 11. Pricing policy<br />

10 - 11. Terms of payment<br />

12. Availability of financial resources<br />

372<br />

Factor Mean weighted score<br />

(Slovenia)<br />

4.70 (1)<br />

4.47 (3)<br />

4,42 (4)<br />

4.40 (...)<br />

4,34 (6)<br />

4,31 (...)<br />

4.21 (10-13)<br />

4.17 (...)<br />

4.12 (...)<br />

4.10 (2)<br />

4.10 (...)<br />

4.04 (...)<br />

Mean weighted score<br />

(Stratos)<br />

4.53 (1)<br />

4.41 (2)<br />

3,81 (11)<br />

4.09 (6)<br />

4,14 (5)<br />

4.22 (4)<br />

3.74 (13)<br />

4.30 (3)<br />

3.80 (12)<br />

3.64 (16)<br />

3.67 (15)<br />

3.96 (8)<br />

Note: 1) A five point scale was used in the assessment: 1 = no importance, 5 = very high<br />

importance<br />

2) In the brackets there are ranks assigned to an individual value or attitude in the<br />

1994 research<br />

3) In the brackets in Stratos research there are ranks assigned to an individual value or<br />

attitude according to the Stratos research.<br />

Main factors influencing the achievement of competitive advantage, shown in<br />

Table 10, give some ground for the conclusion that the product differentiation<br />

strategic orientation dominates in Slovenian firms. The product differentiation<br />

strategy (Porter, 1980: 38) requires a high product quality, reliability of<br />

supplies, well developed and known trademarks, good company reputation,<br />

creativity, and other distinguished characteristics of behaviour. Table 10 shows<br />

that Slovenian firms build their strategic behaviour along these lines. The<br />

product differentiation strategy could focus on a market segment or aim at the<br />

whole market. The first orientation is known as a market niche strategy based on<br />

product differentiation, the second as a product differentiation. It seems that<br />

both of the above mentioned strategic orientations are the most frequently<br />

present in the strategic behaviour of Slovenian enterprises.<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Danijel Pucko / Matej Lahovnik<br />

The collected answers to our questionnaire do not allow us to derive very firm<br />

conclusions regarding the role that the cost leadership strategy has among<br />

different kinds of business strategy in Slovenian enterprises. According to a<br />

modest evidence this kind of strategy has not been in use as frequently as the<br />

other kinds. On the other hand we can not be quite sure that enterprises really<br />

implement a definite kind of generic business strategy in spite of the fact that<br />

they have declared so. There could still be a lot of cases of companies stuck<br />

somewhere in the middle (Porter, 1985: 16-17).<br />

Figure 1: How successful is your firm<br />

6. Where are we and how long will the process of strategic<br />

restructuring take in Slovenian enterprises?<br />

By comparing the assessments of stages in which an individual enterprise is<br />

today or was in 1994, we can come to a conclusion that certain positive results<br />

in the processes of company strategic restructuring have been achieved in the<br />

last two years. As Figure 1 shows only 6.8% of enterprises are confronted with<br />

an acute situation of crisis today. There were 17.2% of enterprises in such a<br />

situation in 1994. 13.5% of enterprises are still in a state of a latent crisis<br />

(Krystek, 1981: 29 and 31) compared to 18.8% in 1994. These indicators show<br />

an evident improvement in the general circumstances in the relevant industries.<br />

On the other hand they warn us that the processes of strategic restructuring of<br />

enterprises will not be terminated soon.<br />

13.8% of managing directors have predicted that the process of strategic<br />

restructuring of their firms would be completed in the current year. One third of<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 373

Managers in the transformation process of Eastern Europe<br />

managing directors (32.5%) predicted that they would need at least two<br />

additional years for the completion of the restructuring process. 16.3% of<br />

enterprises will most probably need between two and four years for their<br />

restructuring. According to predictions 17.5% of firms will need a period that<br />

will span over four additional years. The rest have already completed their<br />

strategic restructuring process or they (6.3% of firms) have had no necessity for<br />

it.<br />

The managing directors' satisfaction with their company profits earned in 1990,<br />

1993, and 1995 differs. By comparing 1993 and 1995, we see that a slightly<br />

higher number of firms achieved better results in the latter year. The<br />

profitability level achieved in 1995 is also slightly better than the one achieved<br />

in 1993 (See Table 11). These indicators are additionally strong arguments and<br />

support the thesis that "old" Slovenian manufacturing enterprises enjoyed some<br />

important positive results when implementing the processes of strategic<br />

restructuring.<br />

Table 11: Satisfaction with profit and profitability levels in Slovenian<br />

enterprises in 1993 and 1995<br />

Degree of satisfaction with<br />

profit :<br />

- more satisfied<br />

- less satisfied<br />

- equally satisfied<br />

374<br />

Year 1993<br />

(% of firms)<br />

Year 1995<br />

(% of firms)<br />

TOTAL 100.0 100.0<br />

Profitability rate:<br />

- negative<br />

- between 0 and 6%<br />

- above 6 - 12%<br />

- above 12% - 20%<br />

- above 20%<br />

TOTAL 100.0 100.0<br />

42.9<br />

41.2<br />

15.9<br />

26.3<br />

59.0<br />

11.5<br />

1.6<br />

1.6<br />

The process of privatisation of the previously socially owned enterprises, which<br />

has been going on intensely since 1995, could be another factor that will<br />

contribute to a further improvement in the performance level of every privatised<br />

company in the near future. 48.8% of managing directors (or members of top<br />

management teams) are convinced this correlation is rather high or even<br />

45.4<br />

39.0<br />

15.6<br />

25.7<br />

51.3<br />

16.2<br />

4.1<br />

2.7<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Danijel Pucko / Matej Lahovnik<br />

extraordinary. Less than a quarter of respondents (22.5%) consider this<br />

correlation low or even non-existent.<br />

7. Conclusion<br />

Slovenia established a democratic political system in 1990 and it became a new,<br />

independent European state in 1991 when the Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia<br />

split apart. Slovenian businesses lost a relatively huge domestic market as a<br />

result of all these changes. The transition in Slovenia has been going on for six<br />

years. In more than two thirds of the Slovenian enterprises the restructuring<br />

processes are not completed yet.<br />

The changes on the positions of managing directors in the firms, carried out in<br />

the transition period, seem to be appropriate and logical enough if we compare<br />

them with findings about relevant changes in the implementation of radical<br />

turnaround strategies in companies elsewhere in the world. Slovenian managing<br />

directors perceive their key strategic tasks in the second stage of the enterprise<br />

restructuring process mostly in the way that could lead to improved<br />

performance of the enterprises.<br />

A value system of the Slovenian managers still differs quite significantly from<br />

the value system of Western European managers. We try to explain this with<br />

some economic and political factors. Slovenian managers have been exposed to<br />

many drastic changes in their economic and political environment in recent<br />

years and they are still more open to changes than their Western European<br />

counterparts. During the transition period many enterprises have chosen and<br />

started to implement some kinds of subcontracting strategy. At least one quarter<br />

of enterprises are vitally dependent on subcontracting now. In the majority of<br />

cases subcontracting relationships have been established with Western<br />

European business firms. It means that a strong integrative link between the<br />

Slovenian economy and the economy of the European Union has already been<br />

developed.<br />

On the other hand a comparison of the personal objectives of the managing<br />

directors and their objectives as employers appear to match quite well with<br />

those of the Western European managers. The objectives of Slovenian<br />

businesses are quite stable during the transition period and are similar to the<br />

most important objectives of Western European businesses.<br />

Factors of the competitive advantages in Slovenian firms are also similar to<br />

those in Western European firms. Most Slovenian firms implement a niche<br />

strategy, a product- differentiation strategy is used by one quarter of Slovenian<br />

firms, and the cost leadership strategy is implemented by one fifth of Slovenian<br />

firms. We may assume that many firms are in Porter's sense "stuck somewhere<br />

in the middle".<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 375

Managers in the transformation process of Eastern Europe<br />

Two thirds of Slovenian managers predict that their firm would need at least<br />

two years or more for strategic restructuring. An important weakness in "old"<br />

Slovenian firms, especially in the last two years, is linked with the<br />

preoccupation of top management teams with the issue of company<br />

privatisation. It has caused some stagnation in solving other important strategic<br />

issues. We can just hope that this weakness is more or less surpassed now, as<br />

privatisation programmes of the majority of enterprises have been already<br />

approved. On the other hand, privatisation has to contribute additionally to the<br />

increase in company performance levels in the near future.<br />

References<br />

Brilmann, J. (1986): Géstion de crise et redressement d'entreprises, Éditions Hommes et<br />

Téchniques, Paris<br />

Goold, M. (1996): Parenting Strategies for the Mature Business, in Long Range Planning,<br />

No.3.<br />

Kilmann, R.H./ Covin, J.T. and Associates (1988): Corporate Transformations, Jossey-Bass<br />

Publishers, London<br />

Krystek, U. (1981): Krisenbewaltigungsmanagement und Unternehmungsplanung, Gabler,<br />

Wiesbaden<br />

Porter, M.E. (1980): Competitive Strategy, The Free Press, London<br />

Porter, M.E. (1985): Competitive Advantage, The Free Press, London<br />

Pucko, D. (1995): Strateško preoblikovanje podjetij: slovenske izkušnje, in: Slovenska<br />

ekonomska revija, No.1-2<br />

Pucko, D. (1995): Strateško preoblikovanje podjetij - kljuèna spoznanja, in: Naše<br />

gospodarstvo, No.5-6.<br />

Regionalna struktura prodaj, nabav, terjatev do kupcev in obveznosti do dobaviteljev<br />

gospodarstva Republike Slovenije po korigiranih podatkih o kuporodajah in drugih<br />

finanènih razmerjih za obdobje 1.1. do 31.12. 1990, Zavod Republike Slovenije za<br />

druzbeno planiranje, Ljubljana, 7.5.1991.<br />

The STRATOS Group (1990): Strategic Orientations of Small European Businesses, Gower<br />

publishing company, Aldershot.<br />

376<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Michel E. Domsch / Uta B. Lieberum / Christiane Strasse<br />

Interkulturelles Personalmanagement in deutschpolnischen<br />

Joint Ventures und deutschen Tochterunternehmen<br />

in Polen. Eine Befragung von deutschen und<br />

polnischen Führungskräften. *<br />

Michel E. Domsch / Uta B. Lieberum / Christiane Strasse **<br />

Die Erschließung des polnischen Marktes hat eine neue Dimension erreicht.<br />

Von Bedeutung sind dabei sowohl landes- als auch unternehmenskulturelle<br />

Aspekte, die ihre Auswirkungen besonders in der Personalentwicklung zeigen.<br />

Durch Interviews von deutschen und polnischen Führungskräften wurden<br />

kulturelle Unterschiede, Aspekte der Unternehmenskulturübertragung und<br />

spezielle Personalentwicklungsmaßnahmen herausgearbeitet. In Verbindung<br />

mit den Internationalisierungsstrategien ergeben sich daraus neue Erkenntnisse<br />

über Chancen und Risiken solcher Kooperationen.<br />

The opening up of the polish Market has reached a new dimension. Aspects of<br />

relevance are especially the corporate and national culture, which have effects<br />

on management development. By interviewing German and Polish executives<br />

the cultural differences and the transfer of corporate cultures as well as special<br />

means of personnell development were examined. In connection with<br />

internationalization strategies the survey produced new findings about chances<br />

and risks of such cooperations.<br />

* Manuscript received: 7.5.97, revised: 5.11.97, accepted: 11.11.97<br />

**<br />

Michel E. Domsch, born 1941, Prof. Dr, Universität der Bundeswehr Hamburg,<br />

Forschungsschwerpunkte: Internationales Management, Frauen im Management/<br />

Chancengleichheit, Human Resource Management, Teilzeitarbeit für Führungskräfte,<br />

Families, work and intergenerational solidarity.<br />

Adresse: Universität der Bundeswehr Hamburg, Institut für Personalwesen und<br />

Arbeitswissenschaft, Holstenhofweg 85, D - 22043 Hamburg.<br />

Email: w_domsch@unibw-hamburg.de<br />

Uta B. Lieberum, born 1963, Dipl.-Kffr., Universität der Bundeswehr Hamburg,<br />

Forschungsschwerpunkte: Internationales Personalmanagement, Chancengleichheit,<br />

Families, work and intergenerational solidarity.<br />

Christiane Strasse, born 1966, Dipl.-Kffr., Universität der Bundeswehr Hamburg,<br />

Forschungsschwerpunkte: Internationales Personalmanagement, Teilzeitarbeit für<br />

Führungskräfte, Families, work and intergenerational solidarity, Selbstentwicklung von<br />

Führungsnachwuchskräften.<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 377

Interkulturelles Personalmanagement in deutsch-polnischen Joint Ventures<br />

1 Einleitung<br />

Auslandsaktivitäten in Osteuropa und in Polen sind ein relativ neues und daher<br />

wenig tiefgreifend behandeltes und erforschtes Thema. Infolge des Umbruchs in<br />

Osteuropa ergibt sich der Bereich des interkulturellen Personalmanagements,<br />

bezogen auf die dafür bedeutsamen Aktivitäten und Kultureinflüsse sowohl für<br />

die Praxis als auch für die Wissenschaft, als ein neues Forschungsfeld.<br />

1.1 Bedeutung des interkulturellen Personalmanagements<br />

Interkulturelles Personalmanagement hat "die ... Aufgabe zu lösen, mit einem<br />

aus zahlreichen Nationalitäten rekrutiertem Personal unterschiedlicher<br />

Kulturkreise und Wertsysteme ... eine einheitliche Unternehmenspolitik zu<br />

verwirklichen" 1 . Eine besondere Rolle spielen dabei die Führungskräfte als<br />

Träger des grenzüberschreitenden Ressourcentransfers im internationalen<br />

Unternehmen. Ihnen obliegt die Anpassung des Unternehmens-Know-how an<br />

komplexe Umweltverhältnisse und neue kulturelle Gegebenheiten. Außerdem<br />

tragen sie die Verantwortung für die Kommunikation über häufig erhebliche<br />

geographische und kulturelle Distanzen 2 .<br />

Durch die unterschiedlichen Rahmenbedingungen in einzelnen Ländern und<br />

deren Einfluß auf die jeweiligen Organisationsmitglieder nehmen die Aufgaben<br />

des Personalmanagements eine besondere Gestalt an. In ausländischen<br />

Niederlassungen stellen sich viele Probleme anders als gewohnt dar. Zu nennen<br />

sind beispielsweise die rechtlichen, politischen und wirtschaftlichen<br />

Rahmenbedingungen, die kulturell geprägten Auffassungen über Arbeit und<br />

Führung oder unterschiedliche Lebensgewohnheiten. In diesem Problemkreis<br />

spielt sowohl die Einbeziehung der Landeskulturen als auch der<br />

Unternehmenskulturen eine Rolle. Durch die Normen und Werte, die das<br />

tägliche Leben und das internationale Geschäftsleben steuern, müssen die<br />

Landeskulturen in internationalen Engagements beachtet werden 3 . Auf<br />

Unternehmensebene können gemeinsame Orientierungen durch die<br />

Unternehmenskultur gegeben sein, die das Handeln der Organisationsmitglieder<br />

prägt 4 . Durch die Transformation osteuropäischer Gesellschaften wird der<br />

Wandel der Unternehmen verstärkt, da dieser mit einem grundlegenden Wandel<br />

1 Sieber, 1973.<br />

2 Vgl. Hoffmann, 1973, S. 19.<br />

3 Vgl. Scholz, 1992, S. 11.<br />

4 Vgl. Schreyögg, 1992, S. 129.<br />

378<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Michel E. Domsch / Uta B. Lieberum / Christiane Strasse<br />

der Unternehmenskulturen verbunden ist, der durch die Investitionen westlicher<br />

Unternehmen zusätzlich beeinflußt wird 5<br />

Den Rahmen für die Interaktion der Personalmanagement-Akteure bildet die<br />

Besetzung der Führungspositionen. Dies gilt auch für das Personalmanagement<br />

von Joint Ventures bzw. Tochterunternehmen in Polen 6 . Dabei muß zusätzlich<br />

die Personalentwicklung betrachtet werden. Diese spielt vor allem für<br />

Investitionen in Osteuropa und damit auch für Polen eine Rolle, da der radikale<br />

Umgestaltungsprozeß besonders die Fähigkeiten und Qualifikationen der<br />

Führungskräfte und Mitarbeiter beeinflußt.<br />

1.2 Deutsche Investitionen in Polen<br />

Durch die Privatisierung und Liberalisierung der osteuropäischen Märkte ist<br />

Osteuropa für viele westliche Unternehmen interessant geworden 7 . So sind die<br />

osteuropäischen Länder sind mehr oder weniger auf die Hilfe des Westens<br />

angewiesen, da sie die Transformation 8 nicht aus eigener Kraft bewältigen<br />

können. Die für ausländische Investoren bedeutsamen Bereiche der<br />

Transformation betreffen die wirtschaftliche Entwicklung der Länder, die<br />

Durchführung der Privatisierung und die rechtlichen Rahmenbedingungen für<br />

ausländische Investoren.<br />

Insgesamt ist die wirtschaftliche Entwicklung in Polen durch ein starkes<br />

Wachstum gekennzeichnet. Im Jahre 1994 wurde eine Steigerung des BIP<br />

(Bruttoinlandsprodukt) von 5% erreicht 9 . Die Inflationsrate lag 1994 bei knapp<br />

30% und die Arbeitslosenquote betrug im Juli 1995 nur noch 15,3%, so daß der<br />

Höhepunkt der Arbeitslosigkeit überschritten scheint 10 .<br />

Für westliche Investoren weist Polen eine attraktive Kombination der<br />

Standortfaktoren auf. So ist nicht nur der weit fortgeschrittene Reformstand von<br />

Bedeutung, sondern ebenfalls das kräftige Wirtschaftswachstum und der große<br />

Markt durch die hohe Einwohnerzahl, die niedrigen Lohnkosten und die<br />

günstige geographische Lage 11 .<br />

5<br />

Vgl. Lang, 1996, S. 7.<br />

6<br />

Vgl. Holtbrügge, 1995, S. 117.<br />

7<br />

Vgl. Kitterer, 1992, S. 160.<br />

8<br />

Vgl Reisinger, 1994, S. 23. Dieser Transformationsprozeß kann als Übergang zwischen<br />

der sozialistischen Planwirtschaft und der funktionsfähigen Marktwirtschaft verstanden<br />

werden.<br />

9<br />

Vgl. Androsch, 1996, S. 89.<br />

10 Vgl. Tkacczynski, 1995, S. 18.<br />

11 o. V., 1995, S. 37.<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997 379

Interkulturelles Personalmanagement in deutsch-polnischen Joint Ventures<br />

Die Anzahl von Unternehmen mit ausländischer Beteiligung hat sich von 867<br />

im Jahre 1989 auf 19.737 im Dezember 1994 und auf 22.053 im Juni 1995<br />

beachtlich erhöht 12 . Polen liegt, verglichen mit den anderen führenden<br />

Reformländern, zwar noch zurück, hat aber in den letzten zwei bis drei Jahren<br />

bezüglich der ausländischen Direktinvestitionen aufgeholt, nachdem sich die<br />

Rahmenbedingungen stark verbessert haben 13 .<br />

Die deutsch-polnischen Beziehungen haben sich in den letzten Jahren in allen<br />

Bereichen positiv entwickelt. Deutschland ist für Polen mit wachsenden<br />

Anteilen der mit großem Abstand führende Handelspartner 14 und nach den USA<br />

der zweitgrößte Auslandsinvestor (Stand 1995) 15 .<br />

Deutsche Investitionen in Polen betragen allerdings nur ca. 1-2 Promille aller<br />

ausländischen Investitionsaktivitäten Deutschlands 16 . Im Vergleich mit der<br />

Tschechischen Republik und Ungarn liegt Polen bei den Osteuropainvestitionen<br />

von Deutschland nur auf Platz drei 17 .<br />

Um das Investitionsrisiko gering zu halten, wählen viele Investoren zunächst die<br />

Beteiligung an bereits bestehenden Unternehmen. Doch seitdem sich die<br />

rechtliche Situation stabilisiert hat, nutzen viele Unternehmen die Möglichkeit,<br />

auch hundertprozentige Tochtergesellschaften zu gründen.<br />

Beide Formen sind die verbreitetsten Möglichkeiten der ausländischen<br />

Direktinvestition, besonders in sich entwickelnden Ländern 18 . Ein allgemeiner<br />

Vergleich zeigt, daß jede Form in bestimmten Bereichen Vorteile hat 19 . Gerade<br />

bei deutschen Investitionen in Polen müssen, ungeachtet der Art des<br />

Unternehmens, verschiedene Einflüsse auf das interkulturelle Personalmanagement<br />

einbezogen werden, um dessen spezifische Ausgestaltung zu<br />

bestimmen. Dabei wird im Gegensatz zu einem rein rechtlichen Joint Venture<br />

von dem Begriff des kulturellen Joint Ventures ausgegangen, der sich auf die<br />

Kultur als geteiltes Risiko, unabhängig von der rechtlichen und finanziellen<br />

Verknüpfung, bezieht.<br />

12 Vgl. Quaisser, 1995, S. 9.<br />

13 o. V. , 1995, S. 36.<br />

14 Vgl. Quaisser, 1996, S. 10.<br />

15 Vgl. Sach, 1995, S. 193f.<br />

16 Vgl. Kalinowski, 1995, S. 112.<br />

17 Vgl. Klingspor, 1992.<br />

18 Vgl. Zeira/Shenkar, 1986, S. 2.<br />

19 Vgl. Chowdhury, 1992, S. 115ff.<br />

380<br />

<strong>JEEMS</strong> 4/ 1997

Michel E. Domsch / Uta B. Lieberum / Christiane Strasse<br />

1.3 Vorgehensweise und Zielsetzung der Untersuchung<br />

Zunächst wird kurz die theoretische Basis der Studie erläutert. Dabei werden die<br />

relevanten Einflüsse auf das interkulturelle Personalmanagement in einem<br />

deutsch-polnischen Joint Venture dargestellt, die sich auf die verschiedenen<br />

Landeskulturen, Unternehmenskulturen sowie ihr Zusammenwirken beziehen.<br />

Aber auch die entsprechenden Internationalisierungsstrategien und die<br />

durchgeführten Personalmanagementaktivitäten werden als relevante Einflüsse<br />

genauer beleuchtet.<br />

Die empirischen Ergebnisse beziehen sich auf die in der Theorie<br />

angesprochenen Aspekte der Untersuchung. Zielsetzung der vorliegenden<br />

Studie ist eine Analyse des interkulturellen Personalmanagements in deutschpolnischen<br />

Joint Ventures und Tochterunternehmen. Dabei wird besonders auf<br />

folgende Aspekte eingegangen:<br />

1. Kulturelle Unterschiede zwischen deutschen und polnischen Führungskräften<br />

als Indikator für grundsätzliche Probleme und Möglichkeiten des<br />

interkulturellen Personalmanagements.<br />

2. Die Besetzung von Führungspositionen im polnischen Unternehmen als<br />

Indikator für die Internationalisierungs- bzw. Kulturstrategie.<br />

3. Die Ausgestaltung der Personalentwicklung als Indikator für die Integration<br />

der polnischen Führungskräfte in das deutsche Unternehmen.<br />