AUR LitPut III Spring 2023 - From Now To Then

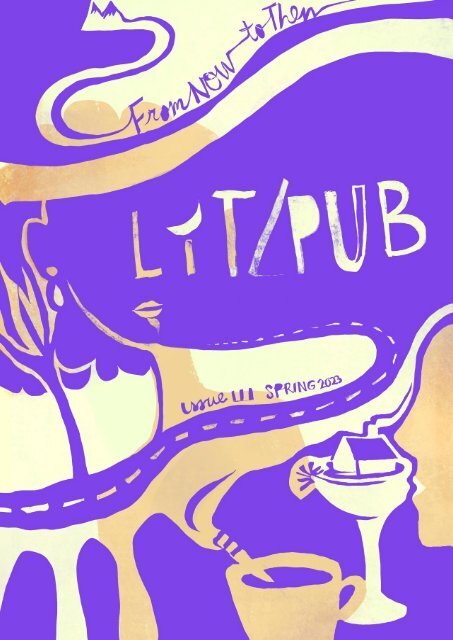

"When I found out about my father’s diagnosis, my first impulse was to light up,” Nalu Gruschkus writes in the opening line of Abnormal Whites and Excessive Blues, her striking piece about her father’s cancer and her own addiction to smoking. In A Bit of Extra Fun, Delaida Rodriguez is having an unpleasant lunch at a restaurant with her boozy mother. Over a chicken sandwich she has barely touched, she peers into her mother’s jade eyes only to realize with dread that she is more like her than she would care to be. Sam Geida looks back in Friday Night Dinners to the glorious family get-togethers at his grandmother’s house – now it’s only a few of them around the same table, with paper plates and the flat blue and white cardboard boxes of Gino’s Pizzeria. The stories in last year’s issue of Lit/Pub were mostly about making sense of things as we emerged from our Covid isolation. The mood is more assertive this year. Isabela Alongi’s vibrant cover design brilliantly evokes a world in movement and young people going places. It is a thread we pick up again in Josephine Dlugosz’s delicate musings (Work of Art), and in the short fiction of Scott Cameron and Raegan Peluso (A Song for Mr Solomon and Two-Faced). The poetry section is especially strong with Gina Carlo’s compassionate trilogy about love and loss and Scott Cameron’s haunting poem about his return to the bleak post-Katrina wasteland. On the lighter side, Lit/Pub spoke to Professor Bruno Montefusco about campus fashion. In the new memoir section, D.P. gives us a tender account of a childhood road trip with her father to Arizona (Snow). And students are traveling again! Emily Chow takes us with her on her intrepid solo trip to Malta. Rome, May 2023

"When I found out about my father’s diagnosis, my first impulse was to light up,” Nalu Gruschkus writes in the opening line of Abnormal Whites and Excessive Blues, her striking piece about her father’s cancer and her own addiction to smoking. In A Bit of Extra Fun, Delaida Rodriguez is

having an unpleasant lunch at a restaurant with her boozy mother. Over a chicken sandwich she has barely touched, she peers into her mother’s jade eyes only to realize with dread that she is more like her than she would care to be. Sam Geida looks back in Friday Night Dinners to the glorious family get-togethers at his grandmother’s house – now it’s only a few of them around the same table, with paper plates and the flat blue and white cardboard boxes of Gino’s Pizzeria.

The stories in last year’s issue of Lit/Pub were mostly about making sense of things as we emerged from our Covid isolation. The mood is more assertive this year. Isabela Alongi’s vibrant cover design brilliantly evokes a world in movement and young people going places. It is a thread we pick up again in Josephine Dlugosz’s delicate musings (Work of Art), and in the short fiction of Scott Cameron and Raegan Peluso (A Song for Mr Solomon and Two-Faced).

The poetry section is especially strong with Gina Carlo’s compassionate trilogy about love and loss and Scott Cameron’s haunting poem about his return to the bleak post-Katrina wasteland. On the lighter side, Lit/Pub spoke to Professor Bruno Montefusco about campus fashion. In the new memoir section, D.P. gives us a tender account of a childhood road trip with her father to Arizona (Snow). And students are traveling again! Emily Chow takes us with her on her intrepid solo trip to Malta.

Rome, May 2023

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Table of Contents<br />

Editors' Note<br />

iii<br />

Prose<br />

Abnormal Whites and Excessive Blues by Nalu Gruschkus<br />

A Bit of Extra Fun by Delaida Rodriguez<br />

Friday Night Dinners by Sam Geida<br />

Work of Art by Josephine Dlugosz<br />

1<br />

6<br />

12<br />

16<br />

Short Fiction<br />

A Song for Mr. Solomon by J. Scott Cameron<br />

Two-Faced by Raegan Peluso<br />

19<br />

22<br />

Poetry I<br />

Three Poems by Gina Carlo<br />

24<br />

The Lit/Pub Interview<br />

King Bruno<br />

31<br />

Poetry II<br />

In the Wake by J. Scott Cameron<br />

34<br />

Memoir<br />

Snow by D. P.<br />

38<br />

Travel<br />

Solo Trip by Emily Chao<br />

43<br />

Cover by Isabela Alongi<br />

i

Special thanks to Marco Parolin, Isabela Alongi and Harry Greiner for their excellent work on the<br />

design, layout and production of the issue. This magazine is a product of<br />

ENG305 - Literary Editing and Publishing<br />

at the American University of Rome.<br />

ii

Editors' Note<br />

"When I found out about my father’s diagnosis my first impulse was to light up,” Nalu Gruschkus<br />

writes in the opening line of Abnormal Whites and Excessive Blues, her striking piece about her<br />

father’s cancer and her own addiction to smoking. In A Bit of Extra Fun, Delaida Rodriguez is<br />

having an unpleasant lunch at a restaurant with her boozy mother. Over a chicken sandwich she has<br />

barely touched, she peers into her mother’s jade eyes only to realize with dread that she is more like<br />

her than she would care to be. Sam Geida looks back in Friday Night Dinners to the glorious family<br />

get-togethers at his grandmother’s house – now it’s only a few of them around the same table, with<br />

paper plates and the flat blue and white cardboard boxes of Gino’s Pizzeria.<br />

The stories in last year’s issue of Lit/Pub were mostly about making sense of things as we<br />

emerged from our Covid isolation. The mood is more assertive this year. Isabela Alongi’s vibrant cover<br />

design brilliantly evokes a world in movement and young people going places. It is a thread we pick up<br />

again in Josephine Dlugosz’s delicate musings (Work of Art), and in the short fiction of Scott<br />

Cameron and Raegan Peluso (A Song for Mr Solomon and Two-Faced).<br />

The poetry section is especially strong with Gina Carlo’s compassionate trilogy about love<br />

and loss and Scott Cameron’s haunting poem about his return to the bleak post-Katrina wasteland.<br />

On the lighter side, Lit/Pub spoke to Professor Bruno Montefusco about campus fashion. In the new<br />

memoir section, D.P. gives us a tender account of a childhood road trip with her father to Arizona<br />

(Snow). And students are traveling again! Emily Chow takes us with her on her intrepid solo trip to<br />

Malta.<br />

Rome, May <strong>2023</strong><br />

iii

iv

Prose<br />

Abnormal Whites and Excessive Blues<br />

By Nalu Gruschkus<br />

"When I found out about my father’s diagnosis, my first impulse was to light up. I started<br />

salivating and my index fingers drummed the picnic table as if to signal withdrawal in morse code.<br />

It was about seven months ago. I hadn’t been home even two weeks from my first year of<br />

college life in Rome. I worked as the pool attendant at The El Rey Court Swim Club, Santa Fe’s<br />

wannabe version of a stuffy, hipster country club. I loathed my job, but the money was good. The best<br />

treat after a grueling eight-hour shift was a Winston Blue. Or two, depending on whether I decided to<br />

take a joyride before making my way home, which was usually the case.<br />

The thing that killed me the most was that he wasn’t even the one who told me.<br />

It was a scorching day in June. I was wearing a white t-shirt that I had cut up and flowy linen<br />

pants to avoid heat stroke. During my lunch break, I sauntered over to the picnic table to meet my<br />

mother and sister. They had brought me a burger from Shake Foundation.<br />

My mind went fuzzy when my mother told me. I couldn’t tell you exactly what she said, but<br />

I can tell you that she was unsure of the words coming out of her mouth. Almost as unsure as I was<br />

hearing them. I was left with a bad taste. Or maybe that was just one of those come and go moments<br />

when your gums bleed. I desperately wanted to conceal all aspects of this new reality with the deepest,<br />

lung collapsing initial drag.<br />

Smoking feels as natural as breathing to me. Maybe even more so at this point. Moving to Italy<br />

was the first real catalyst in turning ‘social’ smoking into chain smoking. Once you graduate with a<br />

masters in chain smoking, quitting is only appealing to the dead. I’d like to make excuses for myself,<br />

but the situation is clearly fucked up; my own father was battling cancer. He wasn’t a smoker and the<br />

1

Prose<br />

cancer wasn’t the lung kind. He had Leukemia. You’d think finding out that my dad had fucking cancer<br />

would have flipped the quitting switch in my addicted brain. But that’s just it. My addicted brain.<br />

It’s not even an addiction to the high. It’s a tactile addiction to the feeling of the butt between my<br />

index and middle finger of my left hand. I’m a lefty by the way. Let’s just say I feel incomplete when I<br />

don’t have a Winston Blue loosely tucked between those two commanding fingers.<br />

Whenever I feel especially guilty about my habit, I try not to be too hard on myself. I always<br />

joke about it saying, ‘Well, at least it’s not heroin.’<br />

I texted my father almost immediately after my mother and sister left. I wasn’t in the right<br />

headspace to call him, nor was he to receive my call. A text would be better for now.<br />

Hey, I heard about the situation. Love you. I have the day off Wednesday so I’ll probably come see<br />

you with mom and Luna. I’m more than happy to cut your hair too.<br />

It took me a while to find the right words. He never was the stereotypical ‘father figure,’ always<br />

more like a friend than anything else. We aren’t related by blood, so we have our own way of talking to<br />

each other. My text reflected that — caring but not in a suffocating way, and the less words the better.<br />

I didn’t want him to know how scared I was deep deep down.<br />

I included the bit about cutting his hair because that was something that we shared, father<br />

and daughter. I later started cutting my mother and my sister’s hair, but it had started as something<br />

between the two of us. I mentioned it in my text because my mother had told me that he wanted me to<br />

cut his hair, but she wasn’t sure if I could handle that. I wasn’t sure if I could either, but I hoped that I<br />

would rise to the occasion without tears.<br />

Smoking is a vice. It’s a coping mechanism that I’ve become fully addicted to. Anytime I feel<br />

the urge to quit, something comes up in my life that dashes my good intentions, and I am off to the<br />

closest tabacchi to shell out another five euros for that ‘last pack.’ Every time I go home, an essential<br />

stop before hopping on the flight is a tabacchi to stock up. In the States, I’m not yet of legal age to<br />

purchase cigarettes, so when I first started smoking at sixteen, it was my scandalous secret. I guess it<br />

was the first time I felt rebellious and grown-up.<br />

A few days later, we drove to Albuquerque. I had my trusty haircutting scissors with me. On<br />

the drive there, I couldn’t breathe. A severe anxiety about erupting in tears when we finally arrived was<br />

2

Prose<br />

strangling me and that all too familiar salivation came around without fail.<br />

As we pulled into his driveway, I caught a glimpse of him hobbling out to greet us. One word<br />

came to my mind. Weak. This weakness was already showing in his stride. Gravel gathered in my<br />

throat. We hugged, and I felt my youthful energy transfer to him as he tightly held on to me for several<br />

seconds.<br />

His house wasn’t a home yet. It remained bare and mostly empty as he had not yet gotten the<br />

chance to fill it with his things that were still tucked away at my mother’s home in Santa Fe and in a<br />

storage unit. There was a lone chair in the so-called living room. He was a minimalist by nature, so he<br />

found comfort in bare space. My mother disagreed, but that’s beside the point. His face was flushed<br />

and lacking any vital color and he was out of breath.<br />

I desperately wanted a cigarette before cutting his hair.<br />

My younger sister wanted to be a part of his haircut. I got territorial, but I let it go, as it always<br />

is with a younger sibling. My father collapsed in the chair and wiped the sweat from his forehead.<br />

Albuquerque is always hotter than Santa Fe, and he didn’t have air conditioning.<br />

“I don’t want it all gone, just trim it as short as you can with scissors. So it’s less noticeable<br />

when it’s falling out in the shower. I’ll use the clippers myself eventually.”<br />

“Just don’t cut yourself when you decide to do that,” my mom interjected.<br />

I cut away somewhat erratically at his thin, wispy hair while we sat in silence and the gravity of<br />

the situation continued to set in. My hands were shaking slightly. My mom bought fresh haircutting<br />

scissors for the occasion, so I set my trusty, albeit dull ones aside. It was blistering outside now, and his<br />

neck and forehead became more and more drenched in sweat. His body appeared limp from sitting in<br />

the chair. He needed to lay down and rest. After I had done a pretty solid once over in length, I handed<br />

the scissors to my sister and guided her little hands to areas that she could fix up.<br />

“Don’t nick his ear.”<br />

Once we had finished, he took a look in the mirror and seemed grateful. We took a family<br />

photo on a timer against the blank white wall in his dining room. It’s a sweet picture that captures the<br />

memory of the beginning stages of our collective journey. I swept up the hair and disposed of it in the<br />

garbage can. Something felt odd about throwing it away. After I finished, he gave me a long, tight hug.<br />

3

Prose<br />

“Thank you, I love you. I’ll see you soon.”<br />

The rest of the summer went by quickly. I was physically and mentally exhausted from working<br />

at my main job, eight hours a day in the boiling sun five days a week. Sometimes I was working<br />

twelve-hour shifts when a wedding needed a busser or waitress in the evenings at El Rey Court. The<br />

other two days of the week, I worked in consignment, eight-hour shifts. What remaining time and<br />

energy I had were dedicated to supporting my family. While I was building my savings for returning to<br />

Rome, I felt the weight of responsibility. I had a lot of time to think about my role in my family as the<br />

eldest daughter and sister; my time home was almost entirely compromised by my various jobs. <strong>Now</strong> I<br />

was going to flit off to Rome again as if everything was fine.<br />

It wasn’t fine. It wasn’t like I was attending a state university, or even an out of state university<br />

where it was easy to catch a flight for a weekend visit. I only visited home twice a year because I live<br />

across the Atlantic Ocean and an eight-hour time difference away. I kept asking myself whether I was<br />

being selfish.<br />

When I thought of how this was affecting my little sister, I shed a lot of tears alone in my car<br />

with a Winston Blue tucked between my fingers, hanging out of the window. I smoked and cried and<br />

got mad at myself for smoking because I didn’t know what else to do. I didn’t know how to fix any of<br />

it and it was the most unsettling feeling I have ever experienced.<br />

<strong>To</strong>wards the end of my time in New Mexico, my father’s younger sister came to stay with him,<br />

temporarily relieving the responsibility from my mother, who was going to Albuquerque several times<br />

a week to take him to and from the hospital. I had lunch with my aunt one afternoon, and I told her<br />

about how guilty I felt about living so far away.<br />

“And you know how close I am with Luna, I feel like I’m not doing enough to support her<br />

and it’s killing me. My mom works so hard to take care of everyone and I don’t want her to burn out. I<br />

feel like I should be staying here where I can step up for everyone involved.”<br />

Rhonda had had cancer too. She’d battled skin cancer and come out of it. I didn’t know this<br />

until my father was thrown into it. Her perspective meant a lot to me.<br />

“Nalu, we are all so proud of you for starting your life so fearlessly in a new country and<br />

following your passion. Your father understands your position and wants nothing more than for you<br />

4

Prose<br />

to thrive and live in your moment. You would be doing him a greater disservice by compromising your<br />

personal progression. He is going to be fine. Luna is going to be fine. We all just have to wait it out and<br />

the best thing you can do for him is show up for him when you can, even if it’s from Rome.”<br />

The last time I was home, which was over winter break this past December, my father finished<br />

his last round of inpatient chemo. We had a celebration. He didn’t want it to be a ‘party.’ He’s not a<br />

party kind of guy and the less fuss the better. My sister and I made a banner that spelled out, “Auguri<br />

papa.” He still has it hanging in his house that is now a home. His home.<br />

On January 20th, I flew back to Rome. On that same day, my father had three major doctor’s<br />

appointments to see if the chemo had worked. I texted him before I left.<br />

Love you, good luck with your appointments today and let me know what you find out.<br />

On January 25th, everything came full circle when my mom texted me this:<br />

Papa’s bone marrow biopsy results just came thru and he is 100% cancer free, all the way down to<br />

the molecular level.<br />

I was in Portugal visiting a friend. “What’s up?” he interjected, taking notice of my eyes welling<br />

up. I quietly recited the text and began to salivate.<br />

H<strong>III</strong><strong>III</strong> mom texted me that your bone marrow biopsy results came thru and you’re cancer free<br />

!!!! I love you so much, I’m so happy and proud of how resilient you’ve been these past seven months.<br />

I shuffled around in my bag looking for my pack as my friend tossed me a lighter. My phone<br />

dinged.<br />

Thanks Nalu! I’m kind of stunned. All that inpatient stuff behind me. Feels strange. But Fantastic!<br />

<strong>Then</strong> I retreated to the balcony and lit up. It only felt right to bookend the journey. As of now,<br />

I plan to quit after college. That gives me two more years to be a fiend. Here’s hoping.<br />

5

Prose<br />

A Bit of Extra Fun<br />

By Delaida Rodriguez<br />

I am like my mother.<br />

I peer into those jade eyes I’ve stared into many times before, my whole life really, and the<br />

harrowing truth becomes clear.<br />

I force myself to break eye-contact and watch as crumbs of bread sprinkle down onto the<br />

white plate in front of me. The wooden table is decorated with floral carvings that match the small<br />

town café’s aesthetic. I pick at the bread of the uneaten sandwich: a cold structure of chicken, lettuce,<br />

and tomato. I prefer to focus on the pale raindrops of dough rather than the silent words that muffle<br />

past my mother’s lips.<br />

I drown out every word she utters, but I can still hear the honeyed voice that has displaced my<br />

own.<br />

It was not some immense moment that triggered my sudden realization. A truth that was<br />

masked for nineteen years. <strong>To</strong>day was a day of routine, a simple drive, the ringing of my cell phone,<br />

followed by a photo that flaunted my mother’s face. It was a blink—a sudden grasp in my heart—<br />

when I saw the truth concealed in the cosmic voids of my subconscious for so long.<br />

I crumble the remaining clumps of bread, and then I pick up a fry. I feel the salt grains between<br />

my thumb and index. I begin to pick it apart. I can’t help it, this urge to pull apart. Better this<br />

french fry than myself.<br />

My attention shifts from the remaining hill of fries to her margarita glass imprinted with the<br />

stain of her wine lipstick, to those jade eyes that I can’t help but look up to again and again. I want<br />

nothing more than to figure out how to shatter the inevitability of genetics. If it is genetics.<br />

6

Prose<br />

How is it possible for one to become another?<br />

On the walk from my car to the café, I once would have noticed the beauty of the trees and the<br />

flowers in bloom. <strong>Now</strong>, I wonder at the wreckage hidden behind each stranger I pass.<br />

“It’s all in your head,” rings my mother’s voice.<br />

All I can think of are her words.<br />

“It’s harder to lose weight than it is to gain. Remember that fat becomes uglier with age.<br />

Think about that before you go eating again.”<br />

<strong>Now</strong> I find myself unable to eat.<br />

She gives me her spiel about my brother’s new therapy and how it’s a waste of time and money.<br />

All I return is a smile and a nod. In the past—before I became her—I would’ve argued against her<br />

views, her hopelessness, and her criticism. But now, I don’t know how to fight her because I don’t<br />

disagree with her.<br />

I flick away the bit of fry from my fingers. I pick up another one, and repeat the process. My<br />

phone vibrates against the table, that damn photo appearing in front of me again. I flip the phone<br />

over, but the photo remains in my mind.<br />

It’s the same picture I’ve had since the day it was taken—parents’ weekend on campus two<br />

years ago. One of those festivals my university hosts, the two of us stumbling through. My first time<br />

drinking with her. There’s a smile etched on my face, I must be happy. But all I hear are her words<br />

after the photo was taken.<br />

“Love, you’re looking a bit homely in those clothes. I don’t want you posting these, they may<br />

give off the wrong impression.”<br />

Conveniently, she never mentioned the traces of alcohol down her shirt. Or her bloodshot eyes<br />

from all the drinking.<br />

I don’t know if she was right about my clothes, but I never did post that photo. Nor did I wear<br />

that outfit again.<br />

My gaze trains onto the crumb covered plate, my reflection staring back at me.<br />

I even look like her.<br />

At least according to my grandmother, my extended family, my friends, her friends, my high<br />

7

Prose<br />

school English teacher, the random stranger who took our order at In-N-Out. The waitress who<br />

brought us our drinks couldn’t help but comment on our resemblance.<br />

“Oh, how you two look so much alike, such beautiful girls. You’re so lucky to have such a<br />

beautiful momma.”<br />

I can’t blame strangers for comparing us. Yet as I peer down at the plate, I try hard not to see<br />

what they see. Pure blonde hair versus dyed-crimson. Jade eyes in contrast to what my grandmother<br />

calls my “miel de sol.” The same blood runs in our veins, but the sun casts different shadows upon us:<br />

her ghostly skin, my natural tan.<br />

My hands run along the mask of scars she etched into my skin. She’ll never have the same scar<br />

on top of her eyelid. She’ll never have the bald spot I can feel if I run my fingers where she pulled out<br />

my hair. Her hands will never have the same wounds mine have. She’ll always deny such things, and<br />

makeup seems to blind her to all she inflicted.<br />

Despite all the differences, the face that looks back at me from across the table is the same.<br />

The averting motion of my eyes resumes. French fries, her fourth glass, strangers strolling by, back to<br />

her eyes. Damn it. Yet as I peer into her jade green, I notice the restive movement of her own pupils.<br />

I see her. I see someone who is just as uneasy being here. Someone who will also fix her gaze on<br />

anything, even the most meaningless object.<br />

She taps her fingers against the side of the recently emptied glass, beckoning the passing waitress.<br />

Her nail chimes against the stained glass, an impatient song ringing through the still air.<br />

“Another?” she asks — a single note, laced with a slur. “With a bit of extra fun in there as<br />

well.”<br />

Her plastered smile hardly hides the fact that she’s already had one drink too many. That with<br />

this next one will come more wounding words about things she hadn’t noticed with her last glass. Her<br />

eyes scan our surroundings before going back to mine.<br />

“Why are you treating your food like a damn toy?”<br />

I break up another fry as the waitress sets down the full margarita.<br />

Focus on something else. My hands, the crumbs that were once food.<br />

Don’t stare at the plate again. A dog walks across the street, it looks like mine.<br />

8

Prose<br />

“You are so lucky to have the food you have, yet here you are wasting it. You can’t be that<br />

fucking picky. Wasting an entire meal, what makes you think you can do that? Especially not here, it’s<br />

too expensive.”<br />

She doesn’t try to hide her scolding from the world anymore.<br />

Listen, there’s a song blaring from that car’s window. Play the melody in the corners of your<br />

mind. Let the lyrics muffle her voice. Pick up another fry. Shit, I really want a drink. I really want her<br />

margarita. One with some of the extra fun inside. Perhaps a bit more than extra.<br />

Her voice amplifies as the car drives away, embracing me again in the cruelty of her words.<br />

“He recommended it for you too. I can’t imagine what your brother was thinking telling me<br />

to pass the message along to you, or what reasoning he would have to associate you with therapy<br />

in the first place. I mean, seriously, there’s nothing in your life that calls for therapy. You have your<br />

phases, but come on, that’s being dramatic now. Suck it up, whatever emotions you think you’re going<br />

through, and stop being so lazy, maybe then…”<br />

On and on she goes, her voice a wind that beats harder with each passing second.<br />

“Are you listening to me?”<br />

Her words grate against my ears and peel back the walls I have built to protect myself from<br />

her. Anyone who’s ever said that damn sticks and stones line has never had lunch with my mother.<br />

“You’re so fucking disrespectful. You answer someone when they are talking to you. Look at<br />

you, you can’t even look into my eyes when I’m speaking.”<br />

Stop. Please, make everything stop. Take a break. Just make everything…<br />

“Stop!” My hands beat down onto the table so hard they make it shake.<br />

The white glass plate crashes to the ground near my feet. The crumbs of fries and bread are<br />

now spread all over the table and concrete floor, the leftovers of the deconstructed sandwich are scattered<br />

near my mother’s spilled margarita.<br />

My knuckles press into the grain of the wood so hard that my fingernails pierce my skin and<br />

blood rushes into my palms.<br />

Take a breath.<br />

9

Prose<br />

<strong>Then</strong> all I see is her, and for once, she sees me.<br />

“Enough, don’t make a scene. You are acting exactly like your father.”<br />

The life around me comes to a halt. A clock ticks in the distance, but the time never changes.<br />

“Mom.”<br />

That’s all I can say. Yet despite the desire to make myself as small as humanly possible, I push<br />

through my clenched jaw and say the words buried inside.<br />

“I don’t want to be you, Mom. I love you. But I don’t want to be you.”<br />

That’s all I can get out. I want to see how she responds before I say anything else. For once, she<br />

is speechless. Her jade eyes are frozen in time, frozen on mine, and for once, I’m the one who gets to<br />

speak.<br />

“In my life, you have not only been my biggest supporter, you have been my biggest abuser.”<br />

That last word trips off my tongue, though it has been spoken a million times in my mind.<br />

“You are the person who taught me to fight for those I love. Who taught me to show strength<br />

when I’m at my weakest, and to stand when everything around has fallen. <strong>To</strong> be honest with who I<br />

am. That’s the problem. I don’t know who I am anymore. No, that’s not true. I’m you.”<br />

Tears swell but never fall. If they did, she’d criticize me for not being able to hold down my<br />

emotions at a moment like this.<br />

“<strong>To</strong> know you’ve left a mark on me more painful than any knife or bullet terrifies me. <strong>To</strong><br />

know that one day I will be too drunk to differentiate if I’m looking at a photo of you or a mirror.<br />

And that one day I will hold such a weight in my heart I will want to bring down those around. Perhaps<br />

going so far that I’d want to cause the same trauma on myself that you have done to me. That,<br />

should I ever have a daughter, she will become the targeted victim of my own pain.”<br />

The way daughters go to their mothers for comfort when they are afraid, I can’t help but do<br />

the same. She’s never helped me escape the monsters under my bed. Why would she help me get rid of<br />

the one she put inside my head? But despite it all, she is my mother.<br />

“Mom, I am scared, more than anything, to be you.” There is nothing left for me to say. Rather,<br />

I’m not strong enough to say anything more.<br />

10

Prose<br />

With one last sigh for relief, I grab the seat from behind and sit down once again, silent. <strong>From</strong><br />

one blink to the next, life resumes.<br />

No one seems to be staring at my mother and me for the disruptive chaos I created. Their day<br />

is still their own to live. Turning back towards my mother, uneasy for what her reaction may be,<br />

I tune in to hear that the words she utters are not the apologies I was hoping for or even a “how dare<br />

you talk back to me in public” scolding. Instead she continues to berate my brother’s recommended<br />

therapy.<br />

The margarita is half full and the glass plate is sprinkled with bread and fry crumbs. The<br />

words in me are still buried, still locked away somewhere deep inside.<br />

Those unspoken words are all I have left of who I am—and that is the reason why they shall<br />

remain unspoken.<br />

11

Prose<br />

Friday Night Dinners<br />

By Sam Geida<br />

My cousin Lissa was walking Grandma Jo Ann through the fairly simple procedure of taking<br />

a picture with an iPhone. Fifteen pairs of knees were crowded around the long, oval table in the beige<br />

dining room. “Well, how was I supposed to know that!” Grandma yelled, her short arms flying in the<br />

air. Roars of laughter filled the room. “Ok! Ok! Settle down, are we ready now?” she asked, looking<br />

through the iPhone camera from her vantage point at the head of the table. All around, red faces<br />

strained to contain the last giggles. Grandma focused up and took the shot. A look of self-approval<br />

shone on her face and spread from one end of the table to the other. <strong>Then</strong>, she grabbed the first dish,<br />

served herself, and passed it on.<br />

These Friday Night Dinners were a weekly family tradition. We would trek from varying corners<br />

of Long Island, New York to Farmingdale. 56 Dean Road was the center of our worlds. We called<br />

it my grandmother’s house, but it was a home for many more family members. Pulling up to the big,<br />

grey house, one saw lights on in every window. Warmth radiated from those little windows all the way<br />

to the long, curved driveway. Up close, the house seemed so big; it was hard to keep the whole structure<br />

in view. Swinging the front door open triggered a loud greeting by all the members of the family<br />

who lived in the house, each beckoning you to their own little corner, each with their own questions,<br />

each of them caring for you in a different way.<br />

Lissa and Aunt Janine lived on the top floor in a converted apartment-like room, coated in<br />

neutral colors and big windows. Aunt Phyllis lived in the basement, a space characterized by atypical<br />

elements – high ceilings and well-composed lighting. Sandwiched between them was the main floor,<br />

and the hidden living quarters of Great Grandma Milly, Great Grandma Rose, Grandpa John, and<br />

12

Prose<br />

Grandma Jo Ann. Apart from the lean hallway that concealed the bedrooms, it was a very open space<br />

where everything converged: family discussions, laughter, play, and most importantly, dinner.<br />

Eight more family members were present in addition to the seven members who already lived<br />

there. After the usual round of greetings and catch up, we all eased into our respective seats around<br />

the table — there was never enough elbow room. We were never on the same page, and conversations<br />

overlapped, news and sports often colliding with good old neighborhood gossip.<br />

The home cooked meals lacked a consistent theme, often reflecting the mood a particular<br />

family member was in when he or she cooked it. The lazy ones prepared a meatloaf and threw it in the<br />

middle of the table for the family to devour. The more creative ones might bring a seafood plate – a<br />

family favorite – and serve it themselves. The only time the room stood still was when jaws were too<br />

busy chewing. There were never any leftovers, a rule of the household. Looking at the pile of empty<br />

dishes and dirty plates, half the family smiled with satisfaction, the other half made quiet promises to<br />

go to the gym the next day.<br />

Dessert was a rarity; coffee, chatter, and laughs worked as a substitute. While parents took on<br />

clean up duty, my cousins and I would run over to our grandparents and great-grandparents and listen<br />

to their stories about how Grandma and Grandpa met or about getting in trouble with their friends as<br />

teenagers. All those stories were filled with life lessons — ones that we all still hold close to heart. This<br />

good cheer continued to echo throughout the first floor until cars started and we were on our way<br />

home, already discussing contributions for the following week’s gathering.<br />

Great Grandma Rose and Great Grandma Milly left the first gaps at the dinner table. But<br />

meals continued to be home cooked, conversation was still lively, often revolving back to our great<br />

grandmas as a way to remember them. “Look at what Milly was able to do for us!” cried out aunts and<br />

uncles as glasses were raised and toasts were made. “Rose was a great lady, always knew how to make<br />

us happy. Let’s live every day like it’s our last!” The power of family and love created a silver lining<br />

through the dark cloud that lurked over the long, oval table. And so the table moved from fifteen to<br />

thirteen.<br />

<strong>Then</strong>, one day, my father gathered my sister and me in the living room of our house.<br />

“Sam, sit down, I gotta tell you something. Grandpa suffered a brain aneurysm last night; he is<br />

13

Prose<br />

in surgery right now. Apparently he is fighting through it, but we will see. Pack up some stuff, we are<br />

going to the hospital.”<br />

What’s a brain aneurysm? I thought to myself.<br />

Grandpa survived, but he wouldn’t have made it long without the help of my grandma. She<br />

became his caretaker, and she no longer was much in the mood to make her grandchildren laugh with<br />

little life stories. Friday Night Dinners became quieter. We didn’t laugh, or even smile, and conversations<br />

were measured. It didn’t seem right to be having a good time when Grandma wheeled Grandpa<br />

up to the table and spoon-fed him like he was a baby. Grandma didn’t cook anymore, and relied on<br />

other family members to bring food to the table. Coffee and conversation didn’t last long as Grandma<br />

and Grandpa were soon off.<br />

He died three years later, and so the official tally fell from thirteen to twelve. At first, some<br />

were a little relieved. Grandma was crushed by her loss but was now free from her caretaking duties.<br />

<strong>To</strong>asts and cheers were made for Grandpa as well, and having Grandma back at the head of the table<br />

was important.<br />

<strong>Then</strong> came Grandma’s unexpected death, and the end of Friday Night Dinners as we had<br />

known them. The gap at the table was too big. Silence filled the first floor of the house. At the table,<br />

those who were left often stared down at her empty seat, lost in a trance.<br />

Grandma was the last of her generation to go. The next generation seemed uncertain and rudderless.<br />

For the first time, there were arguments at the table. Uncles and aunts clashed between empty<br />

chairs. It all seemed a lot of nonsense to me. I drowned it out by listening to myself chew or by closely<br />

examining the pieces of food on my plate. Sometimes, remembering where I was, I ached to stand up<br />

and scream, “What are you guys doing?” Yet I never did. I felt I was too young to understand. Instead<br />

of toasting the great life Grandma lived, we stayed mostly on the surface, making only brief comments<br />

about the food while my cousins and I swapped concerned glances and wondered how this had all<br />

happened.<br />

The room grew emptier and emptier. Sure, knees and elbows had more wiggle room, but the<br />

walls and floors no longer shook with merriment. The arguments scared uncles and aunts away from<br />

the table. My cousins moved to Florida and Maryland to pursue careers in business. It was a slow and<br />

14

Prose<br />

painful unraveling as the table shrunk from eleven to six.<br />

On a recent Friday night, those six pairs of knees moved freely around the table. My father<br />

turned to me and broke the silence.<br />

“Hey Kid, can you pass the salad?”<br />

I grabbed the flimsy tin dish and snapped it over to my dad.<br />

Blue and white cardboard boxes of Gino’s Pizzeria littered the table, filling the room with the<br />

smell of grease. All one heard was the sound of plasticware scratching paper plates.<br />

15

Prose<br />

Work of Art<br />

By Josephine Dlugosz<br />

It’s the first Sunday of the month, and museum entry is free. At La Galleria Nazionale dell’Arte<br />

Moderna, new visitors flood the entrance and old visitors loiter outside, recuperating from museum<br />

fever in the warm February sun. I am among them, but I’ve gathered up enough strength to walk<br />

home.<br />

I cross the street and notice two women in gray winter jackets sitting together at the bottom of<br />

the stairs that lead to Villa Borghese. It’s nearly one in the afternoon, but the winter sun shines directly<br />

on them as if it has just risen. They talk quietly to one another while cars honk over them and stop<br />

abruptly for pedestrians on Viale delle Belle Arti. There is a shadow cast over the bottom halves of<br />

their bodies, but their tops shine in the sun. One of the women, who exhales a mix of smoke and cold<br />

air, glows.<br />

German sociologist Georg Simmel argued, in his essay on urban life, that individuals living in cities<br />

tend to develop a sort of “protective organ.” This organ allows for shelter against the never-ending<br />

emotional and physical stimuli that are omnipresent in a city. Life becomes “matter-of-fact,” he writes;<br />

people develop a “blasé outlook” that allows for protection against sensory overload.<br />

For the first eighteen years of my life, I lived in rural America, and the closest I got to sensory overload<br />

was my school’s cafeteria. My small Connecticut town is nothing extraordinarily special. There are<br />

cows and miles of farmland, and there are old, colonial houses. There is one gas station, and there are<br />

approximately three restaurants. When you visit a grocery store, there is a 99% chance you will run<br />

16

Prose<br />

into someone you know — an ex-partner, perhaps, or your seventh-grade science teacher.<br />

And, much like every other town in America, my town is the land of the automobile. There’s<br />

no way to get around without one, really. People begin driving the second they turn sixteen, some<br />

learn even before that. I knew a boy who learned how to drive a stick shift on his family’s farm. He was<br />

driving John Deere tractors before I’d learned the difference between the gas and the brake pedals.<br />

<strong>From</strong> the moment I turned sixteen, driving felt like the ultimate form of freedom. I got my<br />

license in the middle of the fall and would drive around with the windows down, even after the air<br />

developed a certain chill that only touched the tips of noses and ears. I craved fresh air, of any temperature;<br />

I craved everything that was shielded from me.<br />

I craved humanity, too — something that is so easily avoided back home. The idea of constantly<br />

being surrounded by humans was always alluring to me, and so the city became my dream. I craved<br />

it as much as I craved fresh air; both offered a sort of escape. Every time I’d visit a city, I’d come back,<br />

my head full of colors and inspiration. I’d write stories about people I’d seen on the subway and imagine<br />

their lives. I figured their lives were more interesting and more vibrant than mine had ever been. I<br />

figured they loved city living, too — and then I moved to one.<br />

I remember, during one of my first weeks in Rome, waking up from a nightmare, just before the<br />

sun came up. After a few minutes of restlessness, I stood up and felt the cold marble floor under my<br />

feet. I decided I’d get up, go out, and watch the sunrise.<br />

It was mid-October. The days were hot but the nights were chilly, so I bundled up, forgetting<br />

that extra layers are useless walking in a city; you just sweat right through them. I walked through<br />

Trastevere, emptier than I’d ever seen it and ridden with trash from the night before. I walked over<br />

Ponte Sisto, dodging no one for once, but squinting to block the sun that had finally risen. And eventually,<br />

I made it all the way to the Colosseum, free of humans but full of life.<br />

It was just me and the city, on foot. There was no need for a protective organ then. It was quiet,<br />

bright, and the air was fresh: I had it all to myself. Everything was charming, even the trash. Walk-<br />

17

Prose<br />

ing became my new-found form of freedom in the city, and though it was twice the work than driving,<br />

it was enough for me to fall in love.<br />

But love is complicated.<br />

I’m not so sure I believe in the concept of the “honeymoon phase” in terms of romance. But<br />

when it comes to a new place, I believe in it now.<br />

The protective organ Simmel writes about has grown within me — slowly, steadily, and<br />

unconsciously progressing. When you’ve been in a place for over a year, that place becomes less and<br />

less magical than it once was, because you start to see its scars — and, somehow, you become a part of<br />

them, too. You bleed and get sick and cry and worry, and you want a place to hide.<br />

Back home, cars act as the protective organ cityfolk often have to create for themselves. Windshields,<br />

steel roofs, airbags, tinted windows, and locks often offer more solitude than a city apartment.<br />

We can drive for miles and miles and avoid human interaction. And we can blast music, avoiding<br />

all sounds and sights of humanity, if we really want to.<br />

But we miss out on the beauty: the in-your-face kind you can’t look away from.<br />

Some days, in the city, the organ is more necessary than others. Other days, I forget it exists.<br />

Like on that morning, after leaving La Galleria Nazionale. I’d just spent nearly two hours looking<br />

at art. Klimt and Pollock, Mondrian and Canova. Most of the works on display were objectively,<br />

technically, brilliant, but for some reason, that scene — a scene that I passed by so quickly — struck<br />

me deeper than any brush stroke or chiseled block of marble I’d seen. Suddenly, I remembered why<br />

I’m here.<br />

Here, there is no windshield or tinted window to blur reality. On foot, in the city, it’s all there,<br />

in full three-dimension: two women, some smoke, and the sun. A work of art.<br />

18

Short Fiction<br />

A Song for Mr. Solomon<br />

By J. Scott Cameron<br />

The cicadas surfaced on the east coast the previous Friday. The hissing mass – the hydraulic<br />

combustion of some immense extraterrestrial engine emerging – appeared firstly just south of Chesapeake<br />

Beach, an hour’s drive east of D.C. By Saturday morning, they were suckling on every species of<br />

tree or grass from Key Largo to Asbury Park. The numbers that season caused the ground to balloon<br />

into one veinous abscess along much of the eastern seaboard. As they seeped from the subsoils, enveloping<br />

the surface in their discharge, the turf deflated and then depressed into the emptied nests creating<br />

a sort of trench line. Despite a panic-stricken citizenry and the disastrous effects of the collapse, the<br />

new structure was seen as a fortuitous omen and memorialized into the National Parks System by that<br />

Monday afternoon.<br />

Jake was stirred awake by the chiming of a billion wings. He lay listening to the vibrating<br />

rhythm before slipping back into an unmemorable dream. Two hours later, he would miss the initial<br />

call from his father’s phone. Jake’s hands were too soaked in dish water, and besides it had been nearly<br />

two weeks since they spoke. This would be a long visit. There was a busy Monday ahead and preparation<br />

was necessary before returning the unannounced call. His dad would have expected the delay, per<br />

usual – Jake hated surprises, particularly the calls that had commenced one winter morning three years<br />

prior. He had been quite content with the way things were, but a relationship developed nonetheless.<br />

Mr. Solomon, per usual, would leave some composite of a voicemail, even though he was well aware of<br />

his son's routine. When Jake finished cleaning and organizing, he returned only to find more missed<br />

calls.<br />

“Is this Mr. Solomon?” A strange and pensive youth materialized on his father’s end of the<br />

line.<br />

19

Short Fiction<br />

“Um, yeah. Yes. This is Jacob Solomon.”<br />

“Sir,” the stranger sighed, then sputtered unintelligibles before gathering himself under another<br />

deep breath. “Sir, I have some news regarding your father.”<br />

Jake began to critique the man’s introduction but opted to hold his tongue. “Your aunt came<br />

on over to check on him. The shower was running an’...”<br />

“Thank you, sir. I’m sorry: you are...?”<br />

The man continued to maw on his words as though half his face had fallen slack to shoulder.<br />

It annoyed Jake. You see, he had this theory about people with such an extravagant drawl – some<br />

strange unreasonable manipulation. He just needed to find the proof.<br />

“That’s fine, sir. Thank you. I’m sorry, but again, what’s your name? Who are you exactly?”<br />

Like a worn-out spigot in an unknown neighboring apartment, he dribbled on without any possibility<br />

of cessation. “I spoke with Mr. Solomon, er...hmm. I spoke with your brother, Timothy? Nearly an<br />

hour...”<br />

Jake composed himself and interrupted again. “Sir. Who are you? Why are you on my father’s<br />

phone?”<br />

“Right. Sorry, Sir. I’m Jeremy Mevins. EMT with Mecklin EMS out in Charlotte... They send<br />

us sometimes, on account of Shelby being so small an’ all...”<br />

“And...? Jesus man. Please...get to it.” Jake pressed.<br />

The EMT finally ejected what had been lodged somewhere between his brain and vocal cords.<br />

Jake initially thought to ask how exactly Mevins found himself digging through his father’s phone,<br />

and why he (or anyone) chose cliché, nonsensical phrases like ‘...father was found...,” “...sorry to say...,”<br />

and “...get right to it...,” when no one was lost, one is anything but ‘sorry’ if one takes the time to say<br />

it, and he had clearly done anything but Get. Right. <strong>To</strong>. It.<br />

Instead, Jake felt the more pressing need for a seat, then went straight down to the freshly<br />

cleaned floor, and eventually lay himself flat. Over the years, as the calls were coming through, Jake<br />

would imagine what his father’s responses were going to be. Mr. Solomon was predictably excited for<br />

his son, even when the news was bad.<br />

“No thank you, Mr. Mevins,” he said, before pushing the cell phone across the floor, just out<br />

20

Short Fiction<br />

of arm’s reach.<br />

The cicadas were still singing. <strong>To</strong> tell you the truth, once they surfaced, they never<br />

really stopped. “Singing” may be too delicate a term for some. For some, they scream – a chattering<br />

shriek that shakes the wish from the bone. As Jake lay on the polished floor of his apartment, listening<br />

to the incessant exoskeletal clicking, he thought of fortune, of a beckoning towards summer in symphony,<br />

of an Immortal Cycle through an ever-present Cog, for which each tree was a tooth digging<br />

in and spinning towards some...Constant. A rebirth? Or maybe it was just time to dust off the rain<br />

boots.<br />

The roar accumulated in the leaves, rolled across the landscape in the breeze, resounded off<br />

buildings as it gained momentum, and then stuck, vibrating, an overwhelming mass in the stagnant<br />

morning air of Shelby. Mr. Solomon seemed to have picked the perfect moment in swapping places<br />

with the swarm.<br />

21

Short Fiction<br />

Two-Faced<br />

By Raegan Peluso<br />

"What the fuck do you want?” I can hear his words now, echoing through what’s left of my<br />

mind. It was bad last night. Most nights spent together end in the contemplation of our love and hate<br />

for one another. But this time felt different. Amadeo’s eyes were darkened, and in that moment I did<br />

not recognize him, this man I've tied myself to, given myself to. This time, I pushed him too far.<br />

A red mark is branded on my skin. It aches. It will soon fade away. But a part of me wishes it<br />

would stay forever. That way, I’d be forced to stare reality in its face. Rather than forgetting his rage<br />

and my emptiness at the warmth and familiarity of his skin, I wouldn’t be able to keep looking away.<br />

My shoes catch on one too many loose cobblestones. Is something buried down under there?<br />

Scratching its way out? I kneel down and touch the stones. I feel a faint pulse, but maybe I’m imagining<br />

it. I am crazy, after all. That’s how he makes me feel. That’s what he says.<br />

A mirror leans against the wall on the street. It’s scratched up, cracked at the corners. I crawl<br />

closer to it. Reflecting back at me is a strange thing - this creature with a disintegrating body and lifeless<br />

eyes. She doesn’t look like me. But then again, I often forget what I look like.<br />

“What do you want?” I ask her. It.<br />

“What do you do when you don’t know what you want?” it whispers back.<br />

What do you do when you wish to float along time, past him yelling at you, you pigheaded,<br />

entitled, selfish thing? Past loved ones’ judgment, the bite in their words, their advice you beg for but<br />

never take. Do you stay? Do you walk away?<br />

The child in me used to sing, but this girl can barely open her clenched, closed throat. <strong>To</strong> rasp<br />

a pleading, to emit a call.<br />

22

Short Fiction<br />

For truce.<br />

Break.<br />

Start again?<br />

Never again.<br />

I watch my lips move and recognize the pattern. They’ve danced on my tongue, my mind<br />

before. <strong>To</strong> think I had come so far on this long, treacherous creation of self. I thought I was standing<br />

on solid ground. But in the mirror, I take in my stumbling feet. I see that I’m two steps behind.<br />

“Che diavolo stai facendo?”<br />

I freeze.<br />

Amadeo, approaching me from behind, repeats, “What the hell are you doing?” I’m in the<br />

middle of the road, miles away from my apartment. He must’ve followed me here somehow.<br />

“Nothing,” I blurt. Deflect. Avoid. Get out.<br />

I try to walk away, but I can’t move. He’s got me, my wrist, the entirety of my being. Ignorant.<br />

An echo from last night’s fight. Selfish. It’s all about what you want. A grip of my wrist and his<br />

low rumble. Stop. Walking. Away. He doesn’t say these things to me in this moment, but his words<br />

perpetually get trapped inside my head. I’m a dweller, as Amadeo often tells me. Debilitating, hurtful<br />

words were said, but I am the one who triggered them, and I need to move on. Walk away from how<br />

he hurts you, but don’t walk away from him.<br />

“I don’t want to walk away,” I gasp. Amadeo’s eyes are wide in confusion and pain. Screw you<br />

for screwing this, I scream in my mind, for screwing me, for making me want to walk away.<br />

“But maybe it is you,” the creature in the mirror hisses. “The one who’s screwed him. Who’s<br />

screwed yourself.”<br />

Amadeo steps closer and envelopes me in his arms. At first, I push him away, but then I lean<br />

in. I melt into oblivion. I melt into the cobblestone. I could walk away from this, from us, but he’s got<br />

my hand, and tomorrow will be the same day. <strong>To</strong>morrow, he’ll make me take back what I’m about to<br />

say. So, before I forget what I’ve seen in the mirror, before he makes me take it back, to myself and to<br />

the street, I crawl out from the ancient stone that’s buried me. I whisper what I want.<br />

23

Poetry I<br />

Three Poems<br />

By Gina Carlo<br />

Queen’s Orders<br />

Counterparts and<br />

Shopping carts<br />

Wavering wood<br />

Of broken hearts<br />

Within the walls<br />

Let the games start<br />

The fight for thy hand<br />

Fortify a rampart<br />

Prove themselves valiant<br />

In their own art<br />

In this symphony of swords<br />

Bach and Mozart<br />

One will be held high<br />

In praise and laughter<br />

Have the honour of thy hand after<br />

But one has to<br />

Undoubtedly fall<br />

For love<br />

24

Poetry I<br />

Cannot conquer them all<br />

But that knight will cry a smile<br />

Left for the graves of the dead<br />

As thy, whom he truly loved,<br />

Commands, “off with his head"<br />

I will answer your wishes<br />

Your mind I will ease<br />

I will not fight against this<br />

Be strong and appease<br />

But why<br />

Do my tears fail to cease?<br />

I Have a Plan<br />

I may have found a way to live<br />

Past the horrors this world could give<br />

My love, I dare you to find it as well<br />

It’ll be difficult, but time will tell<br />

The midnight tea with music on<br />

Salty taffy, our favourite songs<br />

The hearth burning bright<br />

Contrasting these frigid nights<br />

Cinnamon scones that Mary makes<br />

Luncheon and brekkie; frosted flakes<br />

Strawberry pillows and soft hair<br />

25

Poetry I<br />

The river’s peak and rainfall air<br />

I may have found a way to survive<br />

Just to know a certain someone’s alive<br />

Just imagine the world we plan to create<br />

Let the horrors of this world disintegrate<br />

Tainted the moment it began<br />

Still, I have a plan.<br />

<strong>To</strong> see the sky when it isn’t blue<br />

Gowns and countdowns, all with you<br />

But those memories of us<br />

Left ourselves in ash and dust<br />

I am excited and thrilled, I admit<br />

No understatement - no words may describe it<br />

I know once you were my biggest fan<br />

But my dear, I have a plan.<br />

The moment you said hello,<br />

Or didn’t even do so<br />

I had a hunch, a sort of clue<br />

What something might’ve meant to you<br />

I didn’t know that I<br />

Would have the privilege of knowing thy<br />

Weak or not, I took it on<br />

26

Poetry I<br />

Acquaintances we were – Long gone<br />

I’d take you back to those days of magic<br />

If time could heal something so tragic<br />

I’m afraid I’ve broken you<br />

And now you know it, too<br />

Repeat after me and you’ll see<br />

I will now set you free<br />

I, myself, will not be bound by the past<br />

And love, not meant to last<br />

These are words and only words, I agree<br />

But you understand what they mean to me<br />

Your walls have been breaking<br />

The holes in your soul left aching<br />

<strong>To</strong>o much to stay sane<br />

Given that once, we were a hurricane<br />

I say I am loyal, write it in words<br />

But lacking trust, I prove myself absurd<br />

My dear old friend<br />

Our christmas is nearing, to an end<br />

I wish for your rest, dear<br />

For that, I must not be here<br />

I will return to my clan<br />

27

Poetry I<br />

Where, of course, I have a plan.<br />

I have found a way to live<br />

It’ll be painful, but worth the give<br />

This Christmas, I’ll still give you my all<br />

But through words, not New Years’ balls<br />

Through smiles made of two texts<br />

There will be no worry nor vex<br />

Forget this love you hold near<br />

So that new dreams may appear<br />

I have found the only way to live<br />

Because you will be determinative<br />

<strong>To</strong> leave me behind<br />

So that you may find<br />

Even if it takes thousands of miles<br />

A truly worthy reason to smile<br />

That will last a great timespan<br />

Does that sound like a plan?<br />

<strong>To</strong> a Wilted Sunflower<br />

It started in two thousand seventeen.<br />

It developed in two thousand seventeen.<br />

But it would never end.<br />

28

Poetry I<br />

Man’s honour.<br />

We were more than lovers.<br />

A duet.<br />

But perhaps the stanzas didn’t fit the song<br />

For who could truly love a tune that, by<br />

Society’s standard, was all wrong?<br />

All the refrains, mixed, did not belong<br />

But who cares?<br />

We had snow angels, fairy lights, and impulsive dares<br />

Spoke past midnight; castles and fairs<br />

The morning was our time,<br />

Our victimless crime<br />

Perhaps that’s the reason– I couldn’t cherish him<br />

That was all... I gave him.<br />

He could have been mine all hours of the day<br />

But with the ante meridiem chose I to stay<br />

Bugger off with it!<br />

For if I chose to turn my back on time<br />

Put my middle finger upon that ticking chime<br />

I was the moon,<br />

He was the sun<br />

And to let the world come between us<br />

What was I thinking, what have I done?<br />

29

Poetry I<br />

Instead of those lunar eclipse gunships<br />

Created by everyone<br />

I could have been focused on the solar eclipse<br />

I’ll even go so far to say<br />

I, even then, missed him every minute of the day<br />

Every second, every hour<br />

I missed my flower<br />

I could have climbed that tower<br />

Used my willful power<br />

<strong>To</strong> move past this pride<br />

But for this self-preservation,<br />

I set him aside<br />

Satisfied with that small hole to hide –<br />

I should have broken it open<br />

Taken a better view<br />

Reached my arms in to finally find you –<br />

Darling,<br />

I’m not prepared to see your ghost.<br />

30

THE LIT/PUB INTERVIEW<br />

King Bruno<br />

Professor Bruno Montefusco teaches the popular Italian Fashion course at The American<br />

University. Born and raised in Rome, he worked in Milan in the eighties. “A truly magical decade,” he<br />

recalls, “with the explosive emergence of ready-to-wear and the rise of Giorgio Armani, the man I call<br />

King Giorgio.”<br />

We caught up with Professor Montefusco on a warm spring day in Garden 2. He was wearing a<br />

mismatched suit – blue jacket and gray trousers - and brightly colored sneakers. A tiny, glittering pin<br />

on his lapel was hardly visible. But when he took it off to show it to us, we saw it made all the difference.<br />

What’s with the mismatched suit, Professor?<br />

“In Italian fashion there is always a tendency to match things that are not supposed to be together. It’s<br />

part of what we call sprezzatura – a studied effortlessness. The lavender blue jacket I am wearing has its<br />

own trousers, and these gray trousers have their own jacket. But sometimes I like to mix them up. And<br />

when I mix them up, I like to add a touch of irony. <strong>To</strong>day I wanted to dramatize the suit with a pair of<br />

beautiful sneakers. They don’t match, but I like the casual look they create.”<br />

Do <strong>AUR</strong> students have a casual look? On our way here we passed students sporting baggy pants, neutral<br />

colored tops, and high-end handbags….<br />

“Yes, students dress very casually on campus. But it’s a different kind of casual. When I look around I<br />

31

THE LIT/PUB INTERVIEW<br />

don’t see any particularly brilliant or exciting outfit, mostly comfortable ones. Sometimes I see American<br />

students get too casual. They put on the first thing they grab from their closet. Italian casual is<br />

completely different: it is a very careful selection of tops and pants.”<br />

But do you recognize a style on campus?<br />

“<strong>AUR</strong> students are fashionable in their own way. They don’t follow big Italian brands, which makes<br />

sense because they are very young. They seem more interested in alternative brands or in street fashion,<br />

which can inspire innovation. Fashion by its very nature is always evolving, always in movement.”<br />

Does style reflect identity?<br />

“Yes. How we dress reveals that inner self that we sometimes hide, not only from others, but from ourselves.<br />

Fashion speaks for us. This idea was first developed by the French philosopher Roland Barthes<br />

in The Language of Fashion, and is at the core of my course. There are days when I ask my students to<br />

come dressed as they really want to be dressed. I also organize photo-shoots and allow them to express<br />

themselves. And they do. But – and please don’t take this the wrong way - I do think American boys<br />

and girls are a little bit obsessed by the way they are judged.”<br />

Italians are not as obsessed?<br />

“We Italians don’t care. And so we are freer, in a way, to express ourselves. It didn’t used to be this<br />

way. It is a recent phenomenon, an evolution of Italian society. And fashion is a mirror of society, an<br />

expression of every day reality.”<br />

You often tell your students that fashion is revolution. What do you mean?<br />

“Every six months, and now every month thanks to smaller ‘capsule’ collections and new lines, the<br />

32

THE LIT/PUB INTERVIEW<br />

perception of fashion changes. So it is revolutionary. And democratic.”<br />

How so?<br />

“We have to be open minded about ideas and suggestions that come from the new generations. Young<br />

people are increasingly aware of fashion, and of the ways fashion can be used to achieve specific goals,<br />

especially through social media. Take the new trend for genderless fashion, for example.”<br />

Genderless fashion has been around for some time.<br />

“Not everywhere, and not so much in Italy. Gender issues are just now entering Italian fashion, ten or<br />

fifteen years after French, German, and Nordic fashion. Italians are very traditional. But nowadays, a<br />

young Italian who wants to paint his nails can do it! Could he ten years ago? No. If you follow fashion,<br />

if you’re passionate about it, you have to follow change.”<br />

Are you happy with the progress your students have made?<br />

“I have eighty-five students this semester. And I can tell you they are now very careful about what<br />

they wear. They have started to pay attention to matching colors and accessories. And they send me<br />

pictures from the fashion district in Milan or from the shops in Rome where they buy clothes. But I<br />

hope my students take away this: fashion is not about money, it is about well-being. It is a way to feel<br />

better about yourself.”<br />

Do you always dress for class?<br />

“I am a fashion professor and how I dress is important. I am a living shop window for clothes.”<br />

(with special thanks to Kirsten Galbraith)<br />

33

Poetry II<br />

In the Wake<br />

By J. Scott Cameron<br />

The fog sits like a bed skirt this time of morning<br />

– grayish white pleats below<br />

a slow, pulsing illumination that hints<br />

at a place of respite.<br />

The sky is cast-iron.<br />

The sun, a pilot light<br />

prepared to propel to its crest<br />

and back again –<br />

perpetual –<br />

a Peaceful Projectile counterpoised<br />

until maybe half past six, when<br />

it erupts into presence<br />

and the fixed mist is mixed back<br />

into the heavy humidity<br />

ever present this far below sea level.<br />

Eventually, we wade through<br />

and reach for the truck’s door handles.<br />

A lottery ticket put us on this trip –<br />

a turn to inspect whatever<br />

Remains.<br />

34

Poetry II<br />

We turn left out of the driveway,<br />

then right<br />

into a pensive, inchworm crawl.<br />

All that is left is<br />

Patience.<br />

Fifty thousand other winners for the day<br />

work their way<br />

along the stretch, bordered<br />

by blinking lights –<br />

a tarmac glittering in<br />

red-carpet delight.<br />

A runway for the hopefuls.<br />

Patriotic red-white-blue,<br />

Red-White-Blues…<br />

The occasional orange-yellow,<br />

Orange-Yellows<br />

fly by, flickering<br />

along the edges of our path,<br />

accompanied by a hum<br />

Behind,<br />

Aside,<br />

In front –<br />

Police Caravan,<br />

followed by<br />

Corps of Engineers Caravan,<br />

followed by<br />

News Station Caravan.<br />

35

Poetry II<br />

A constant, low thump is<br />

overhead –<br />

Patrol chopper,<br />

Army chopper,<br />

News chopper,<br />

Chopping:<br />

conveyor belt sushi<br />

with sparklers,<br />

dulling the appetite like<br />

the smell of sulfur<br />

singed skin<br />

and a stomach that knows best.<br />

The outline comes into view<br />

about noon, an Oz already conquered.<br />

The front wheels plunk<br />

off the causeway, falling<br />

from a star like a miracle.<br />

(Claps from the back seat.)<br />

Camouflage Humvees zipper<br />

the caked highway, barely visible<br />

among the sound walls – layered<br />

like Hiroshima sunsets into early '46.<br />

All fifty thousand, in front and behind,<br />

a simmering iridescence<br />

in the surrounding grays and browns.<br />

We roll through yet unblemished<br />

layers of the sunbaked silt – the fresh<br />

crunch of that chance path<br />

36

Poetry II<br />

signaling<br />

Christmas Morning Bubble Wrap<br />

Explosions.<br />

Something Primitive<br />

in the satisfaction.<br />

The motion begins a slalom through an<br />

obstacle course of equally gray-brown and<br />

once properly placed objects: overturned<br />

vehicles of every necessity and leisure,<br />

refrigerators laid on side – flayed,<br />

open, exposed, insides tumbling out<br />

– square soot-covered seppuku<br />

carcasses.<br />

In the lethargic heat of this summer afternoon,<br />

the ‘Xs’ hang heavy<br />

on every exhausted exterior, sagging<br />

with Search-and-Rescue Codes too<br />

numerous to count. And like those<br />

scraping through the remnants in<br />

mid-August ’45, flipping<br />

pieces of pocked concrete clinging<br />

to sheared rebar –<br />

a certainty of security in the future<br />

lost from only moments ago –<br />

we confirm, against all callus and<br />

craving, there is no reason to return.<br />

37

Memoir<br />

Snow<br />

By D. P.<br />

Growing up in the flat marshlands of Florida, snow was an abstract concept. I understood<br />

every scientific and meteorological explanation of it as a state of water, but I couldn’t fathom how it<br />

might feel to hold snow in my hand or squish snow under my feet. In my imagination, influenced by<br />

Christmas movies and elementary science textbooks, snow was cold and soft and somehow supposed<br />

to be touched, a bit like Play-Doh. As a kid in Florida I never missed snow or craved the experience of<br />

it; still, the idea of it awoke in me a curiosity akin to my persistent love for digging holes in the dirt or<br />

weaving furniture from fallen pine needles.<br />

In the winter of 2008 my dad woke my sister and me with his typical booming rooster’s call.<br />

We were in the car in a matter of minutes. We always listened to Dad’s orders, but I remember the<br />

maneuver from bed to car was especially prompt that morning because I had packed everything with<br />

careful diligence the night before. My sister and I had prepared ourselves for the thirty-hour drive as if<br />

we’d done it several times before. I settled behind the front passenger’s seat so I could admire my father<br />

while he drove. We were traveling to Show Low, Arizona, to visit his mother, whom I’d never met<br />

before. Most importantly, we were driving to a settlement in the White Mountains, where, I was told,<br />

there would likely be snow.<br />

Driving through the state of Florida needs no description. Even then I could feel that the six<br />

hours we spent flying upwards through the Western half of the peninsula amounted to nothing but<br />

wasted time, significant only in that it was necessary to exit the state of Florida. Flat as flat comes and<br />

without a glimpse of the ocean, the I-75 marks the end of driving as a leisure activity and the beginning<br />

of driving as an obligation. My dad honored the weight of obligation by pushing 100mph from<br />

38

Memoir<br />

Tampa to Pensacola, where we had to stop at a gas station to ‘wait-out’ the tropical storm that was<br />

ripping up streetlights and tossing oak trees in our path.<br />

In the gas station bathroom, I asked my sister if she thought Dad was a good driver. She said<br />

that it didn’t matter because we didn’t know how to drive, and he wouldn’t let his girlfriend drive anyway.<br />

I was a small nail-biting know-it-all blossoming into a young woman with a full-blown anxiety<br />

disorder. Once my sister and I were the only two occupants of the girl’s bathroom, I nervously whispered<br />

to her: “You know, the reason we eat pancakes five nights a week is because Bisquick is cheap<br />

and dad is poor. If he gets pulled over they will take all the money we have left for this trip and we<br />

won’t even have any more money for Bisquick. And if he gets pulled over while he is smoking pot, the<br />

police will have to take us away.” My sister shrugged as if I’d told her the earth was round.<br />

We had already been driving 12 hours by the time we reached Texas. I let out a big sigh from<br />

the back of the car when we crossed the state line, trying to signal to daddy that I felt for him. Back in<br />

Florida, he had told me that Texas was the “driest, most miserable shithole” imaginable and that it’d<br />

be the last challenge of our 30-hour drive. I’d never been to Texas and I’d only feigned compassion so<br />

Dad would know I loved him; what I hadn’t expected was that all of what he’d said was true except<br />

that he’d failed to mention the infinity of the shithole. My dad’s girlfriend, Megan, tried to lull me to<br />

sleep, gently assuring me I wouldn’t miss anything if I slept for a couple of hours. But I could not sleep<br />

because I knew that if my eyes weren’t on the road I could not be sure that my dad’s were either. Every<br />

time I thought his head was bobbing I twisted my neck to look at his face, certain that he was nodding<br />

off and that we were going to fly into the metal barrier at 100mph.<br />

The cracking Texan land sprawled on and on in the night, the blinking lights of RV grounds<br />

and fuel stations dancing to Roger Water’s guitar solos that penetrated the otherwise silent car. I<br />

wondered about this grandma whom I’d never met before. Until I was eleven years old, I assumed that<br />

my paternal grandfather’s Scottish wife was my biological grandmother though I had probably been<br />

told otherwise. I was perplexed when my father said to me that I had another grandmother, his biological<br />

mother, in Arizona. I knew that we were visiting because her husband had just passed, and my<br />

father had offered to help clean his estate. Earlier in the drive, my dad had told my sister and me about<br />

an incident from his childhood: when he was ten years old, he returned home from school to find his<br />

mother being carried away in a stretcher after a botched suicide attempt. When she passed him on the<br />

39

Memoir<br />

stretcher in the backyard, she told him (my dad lifted his finger and pointed to my sister and me while<br />

imitating his mother in a raspy voice) to never, ever trust a woman. My father repeated her words as if<br />

they were a prophecy and it would be years before I realized the significance of this incident.<br />

In El Paso my dad pulled over at a rest stop for a nap. He smoked a joint inside the car with<br />

the window up, a commonplace occurrence that he’d justify by explaining that new research was<br />

dispelling all the old propaganda regarding passive smoking. I loved when my father smoked. In many<br />

of my memories his laughing face is peering back at me through a thick cloud of suspended smoke. I<br />

loved the way I would relax as the vapor descended upon me and I heard my dad’s big teeth chuckling<br />