You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Unfortunately, what most people don’t realize is that dieting<br />

may be causing more harm than good. Ninety-five per cent of<br />

all dieters will regain the weight lost within one to five years<br />

(Grodstein et al 1996 & Neumark-Sztainer et al 2007).<br />

The failure of diets can be explained by the “dieter’s dilemma” as<br />

coined by psychologists John Foreyt and Ken Goodrick, which<br />

is triggered by the desire to be smaller, which leads to dieting.<br />

Dieting leads to food preoccupation and food cravings through<br />

a cascade of neurotransmitters and chemical hormones in the<br />

brain. Eventually the dieter gives in to the strong food cravings,<br />

overeats, and regains the lost weight. The individual is back to<br />

square one, with a desire to lose weight.<br />

People often mistake the natural biological response of hunger<br />

for lack of willpower when they succumb to strong cravings, but<br />

this isn’t the case. As the cycle repeats, the dieter feels more out<br />

of control and self-esteem decreases. If diets were successful, we<br />

wouldn’t have so many unhappy and confused people seeking<br />

out help for health and weight loss. The diet industry has<br />

corrupted the word “wellness,” and it has now become almost<br />

synonymous with dieting. Part of the path to healing one’s<br />

relationship with food is recognizing the damage dieting has<br />

done to mental health and psychological well-being.<br />

Why is it that we rely so heavily on others’ opinions and advice<br />

when it comes to eating? Food is a necessity of life. It provides<br />

fuel for the body in addition to all the nutrients we require to<br />

function efficiently. Yet many people don’t trust their bodies to<br />

tell them when or what to eat. Instead, they reach out to others<br />

for advice. Have you ever stopped to ask yourself how someone<br />

else could possibly know when you are hungry or full? This is<br />

the backbone of diets, telling you how much and what to eat,<br />

giving no thought to your internal cues.<br />

Food is required for survival just like breathing, water, shelter<br />

and sleep. When swimming under water, would you seek out<br />

advice from others before coming up for air? When you need<br />

to use the washroom, do you question the urge, thinking you<br />

couldn’t possibly have to go again? When it comes to breathing,<br />

sleeping, thirst and shelter, we have more confidence trusting<br />

our bodies, however, the same can’t be said about food. The<br />

more a person looks to others for diet advice, the more confused<br />

they become and the less they trust their (own) body. If dieting<br />

is an unhealthy approach, then what can we do to foster a good<br />

relationship with food and improve our health?<br />

Enter “intuitive eating,” which is a self-care eating framework<br />

that integrates instinct, emotion, and rational thought (Tribole,<br />

2107). It means getting back to your roots – trusting your body<br />

and your signals. The human body is hardwired to know when<br />

and how much to eat, however this concept is often lost in<br />

translation due to external influences. Intuitive eating is based<br />

on principles that help people let go of their rigidity around<br />

food by rejecting diet culture and giving permission to eat in a<br />

way that feels good in their body and honours their health.<br />

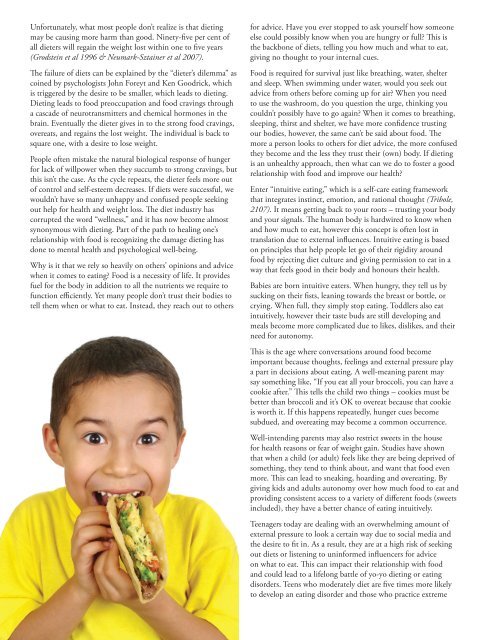

Babies are born intuitive eaters. When hungry, they tell us by<br />

sucking on their fists, leaning towards the breast or bottle, or<br />

crying. When full, they simply stop eating. Toddlers also eat<br />

intuitively, however their taste buds are still developing and<br />

meals become more complicated due to likes, dislikes, and their<br />

need for autonomy.<br />

This is the age where conversations around food become<br />

important because thoughts, feelings and external pressure play<br />

a part in decisions about eating. A well-meaning parent may<br />

say something like, “If you eat all your broccoli, you can have a<br />

cookie after.” This tells the child two things – cookies must be<br />

better than broccoli and it’s OK to overeat because that cookie<br />

is worth it. If this happens repeatedly, hunger cues become<br />

subdued, and overeating may become a common occurrence.<br />

Well-intending parents may also restrict sweets in the house<br />

for health reasons or fear of weight gain. Studies have shown<br />

that when a child (or adult) feels like they are being deprived of<br />

something, they tend to think about, and want that food even<br />

more. This can lead to sneaking, hoarding and overeating. By<br />

giving kids and adults autonomy over how much food to eat and<br />

providing consistent access to a variety of different foods (sweets<br />

included), they have a better chance of eating intuitively.<br />

Teenagers today are dealing with an overwhelming amount of<br />

external pressure to look a certain way due to social media and<br />

the desire to fit in. As a result, they are at a high risk of seeking<br />

out diets or listening to uninformed influencers for advice<br />

on what to eat. This can impact their relationship with food<br />

and could lead to a lifelong battle of yo-yo dieting or eating<br />

disorders. Teens who moderately diet are five times more likely<br />

to develop an eating disorder and those who practice extreme