YSM Issue 96.2

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

FEATURE<br />

Palaeogenomics<br />

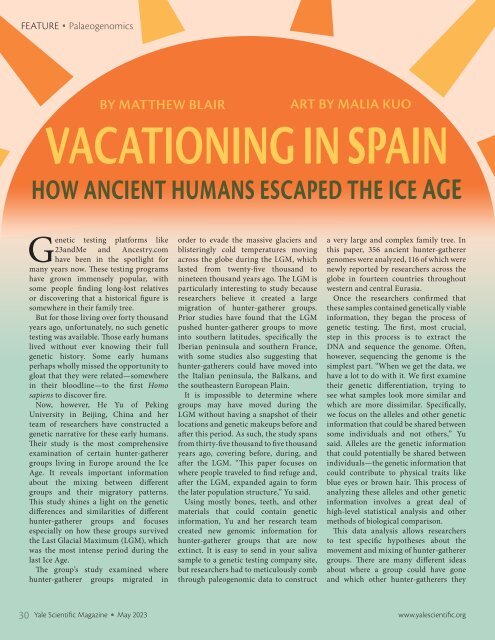

BY MATTHEW BLAIR<br />

ART BY MALIA KUO<br />

VACATIONING IN SPAIN<br />

HOW ANCIENT HUMANS ESCAPED THE ICE AGE<br />

Genetic testing platforms like<br />

23andMe and Ancestry.com<br />

have been in the spotlight for<br />

many years now. These testing programs<br />

have grown immensely popular, with<br />

some people finding long-lost relatives<br />

or discovering that a historical figure is<br />

somewhere in their family tree.<br />

But for those living over forty thousand<br />

years ago, unfortunately, no such genetic<br />

testing was available. Those early humans<br />

lived without ever knowing their full<br />

genetic history. Some early humans<br />

perhaps wholly missed the opportunity to<br />

gloat that they were related—somewhere<br />

in their bloodline—to the first Homo<br />

sapiens to discover fire.<br />

Now, however, He Yu of Peking<br />

University in Beijing, China and her<br />

team of researchers have constructed a<br />

genetic narrative for these early humans.<br />

Their study is the most comprehensive<br />

examination of certain hunter-gatherer<br />

groups living in Europe around the Ice<br />

Age. It reveals important information<br />

about the mixing between different<br />

groups and their migratory patterns.<br />

This study shines a light on the genetic<br />

differences and similarities of different<br />

hunter-gatherer groups and focuses<br />

especially on how these groups survived<br />

the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), which<br />

was the most intense period during the<br />

last Ice Age.<br />

The group’s study examined where<br />

hunter-gatherer groups migrated in<br />

order to evade the massive glaciers and<br />

blisteringly cold temperatures moving<br />

across the globe during the LGM, which<br />

lasted from twenty-five thousand to<br />

nineteen thousand years ago. The LGM is<br />

particularly interesting to study because<br />

researchers believe it created a large<br />

migration of hunter-gatherer groups.<br />

Prior studies have found that the LGM<br />

pushed hunter-gatherer groups to move<br />

into southern latitudes, specifically the<br />

Iberian peninsula and southern France,<br />

with some studies also suggesting that<br />

hunter-gatherers could have moved into<br />

the Italian peninsula, the Balkans, and<br />

the southeastern European Plain.<br />

It is impossible to determine where<br />

groups may have moved during the<br />

LGM without having a snapshot of their<br />

locations and genetic makeups before and<br />

after this period. As such, the study spans<br />

from thirty-five thousand to five thousand<br />

years ago, covering before, during, and<br />

after the LGM. “This paper focuses on<br />

where people traveled to find refuge and,<br />

after the LGM, expanded again to form<br />

the later population structure,” Yu said.<br />

Using mostly bones, teeth, and other<br />

materials that could contain genetic<br />

information, Yu and her research team<br />

created new genomic information for<br />

hunter-gatherer groups that are now<br />

extinct. It is easy to send in your saliva<br />

sample to a genetic testing company site,<br />

but researchers had to meticulously comb<br />

through paleogenomic data to construct<br />

a very large and complex family tree. In<br />

this paper, 356 ancient hunter-gatherer<br />

genomes were analyzed, 116 of which were<br />

newly reported by researchers across the<br />

globe in fourteen countries throughout<br />

western and central Eurasia.<br />

Once the researchers confirmed that<br />

these samples contained genetically viable<br />

information, they began the process of<br />

genetic testing. The first, most crucial,<br />

step in this process is to extract the<br />

DNA and sequence the genome. Often,<br />

however, sequencing the genome is the<br />

simplest part. “When we get the data, we<br />

have a lot to do with it. We first examine<br />

their genetic differentiation, trying to<br />

see what samples look more similar and<br />

which are more dissimilar. Specifically,<br />

we focus on the alleles and other genetic<br />

information that could be shared between<br />

some individuals and not others,” Yu<br />

said. Alleles are the genetic information<br />

that could potentially be shared between<br />

individuals—the genetic information that<br />

could contribute to physical traits like<br />

blue eyes or brown hair. This process of<br />

analyzing these alleles and other genetic<br />

information involves a great deal of<br />

high-level statistical analysis and other<br />

methods of biological comparison.<br />

This data analysis allows researchers<br />

to test specific hypotheses about the<br />

movement and mixing of hunter-gatherer<br />

groups. There are many different ideas<br />

about where a group could have gone<br />

and which other hunter-gatherers they<br />

30 Yale Scientific Magazine May 2023 www.yalescientific.org