Angelus News | March 22, 2024 | Vol. 9 No. 6

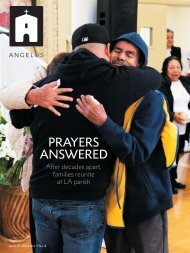

On the cover: To cap off a nearly five-decades-long career working in Church communications, Francis X. Maier had an ambitious book idea: a ‘snapshot’ of the Church in America at this time in history that captured both its strengths and its sicknesses. On Page 10, Maier shares what he took away from hearing more than 100 “confessions”’ with American Catholic leaders for the project. On Page 20, John L. Allen Jr. offers his own diagnosis of the uneasy relationship between U.S. Catholics and Rome during the Pope Francis pontificate.

On the cover: To cap off a nearly five-decades-long career working in Church communications, Francis X. Maier had an ambitious book idea: a ‘snapshot’ of the Church in America at this time in history that captured both its strengths and its sicknesses. On Page 10, Maier shares what he took away from hearing more than 100 “confessions”’ with American Catholic leaders for the project. On Page 20, John L. Allen Jr. offers his own diagnosis of the uneasy relationship between U.S. Catholics and Rome during the Pope Francis pontificate.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

elative — even just to spend time with them — can be<br />

considered a corporal work of mercy.<br />

And an aging society will provide plenty of opportunities to<br />

engage in that kind of charity. The federal Administration<br />

on Aging estimates that 70% of adults 65 and over will need<br />

some kind of long-term care assistance, services, or support in<br />

their remaining years. This isn’t intensive medical treatment;<br />

just a helping hand with daily activities like preparing food,<br />

bathing, or using the bathroom. On average, seniors need this<br />

type of care for about three years, though for some the need<br />

can stretch out much longer.<br />

For many, family is the first and primary caretaker. Many<br />

seniors know they can rely on one or more of their children<br />

to attend to some of their more basic needs. But those needs<br />

often require more constant time and attention than adults<br />

with their own children to care for can devote. A report from<br />

the Pew Research Center found that more than half of adults<br />

in their 40s are members of the so-called “Sandwich Generation”<br />

— those who have an elderly parent while also raising<br />

at least one child at home.<br />

And for other seniors, family isn’t a viable option. Broken<br />

relationships, alienated children, divorce; all can mean a<br />

fracturing of the safety net that family is meant to provide.<br />

And with more Americans opting out of parenthood altogether,<br />

an increasing share of adults will enter their senior years<br />

with thinner family trees, and fewer people to visit them in<br />

retirement, an assisted-living facility, or hospice care.<br />

Family members from different generations attend an encounter and Mass for the elderly led by Pope Francis in<br />

St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican in this 2014 file photo. | CNS/PAUL HARING<br />

These trends will put increasing pressure on a social system<br />

that has not adjusted to the new realities of smaller families<br />

and longer lives. Caring for the elderly is inherently labor-intensive<br />

— it’s a one-to-one service that often requires some<br />

level of trust, even intimacy. Like child care, it’s a job that<br />

can’t become more “efficient” or “productive” without losing<br />

quality. A recent research paper found that when private<br />

equity firms took over a nursing facility, profits went up and<br />

patient outcomes — including mortality — took a turn for<br />

the worse.<br />

In Japan, they are seeking to supplement their senior care<br />

with robots trained to change bedpans, remotely monitor vital<br />

signs, and — more speculatively — engage in conversation<br />

to provide a simulacrum of social engagement. According to<br />

the MIT Technology Review, the Japanese government has<br />

spent more than $300 million on research and development<br />

for these new devices, though they remain niche, rather than<br />

mainstream, devices so far.<br />

One does not need to be a smartphone-avoiding Luddite<br />

to be skeptical of the idea of innovating our way out of the<br />

increasing demand for elder care. Technology could be used<br />

in some cases — like monitoring a senior’s apartment for<br />

falls — but can never be expected, or desired, to replace the<br />

human connection of a relationship with a caregiver. If anything,<br />

these advances mean our seniors need more in-person<br />

relationships and interactions, not fewer.<br />

Medicaid, for example, won’t pay for personal care for<br />

seniors. So for many Americans, the primary vehicle for most<br />

Americans to access care in their senior years is through<br />

long-term care insurance. Yet the market for such services has<br />

real problems: The number of options available to individuals<br />

fell from 125 two decades ago to under 15 more recently,<br />

according to the American Action Forum. Washington state<br />

recently rolled out a new state tax aimed at providing longterm<br />

care to residents, but it has been plagued with difficulties<br />

and it is unclear whether it will<br />

collect enough revenue to solve the<br />

looming problem.<br />

The looming crisis of senior care will<br />

likely require touching some political<br />

third rails. Allowing Medicaid to pay<br />

for long-term care, for example, will<br />

dramatically increase its expenditures<br />

and worsen our nation’s fiscal picture,<br />

especially if we seek to raise wages<br />

for home health aides. As the whole<br />

economy has recently experienced, a<br />

world with declining birthrates means<br />

fewer workers and increased labor<br />

shortages — especially in labor-intensive<br />

jobs like child and elder care.<br />

It may be the case that the need for<br />

home health care aides and nursing<br />

home staff spurs America to revisit its<br />

immigration policy before too long.<br />

And any step toward broader public<br />

funding will almost certainly require<br />

higher taxes.<br />

Solving these problems may sound<br />

like drudgery. Yet if we don’t tackle the financial side that<br />

makes aging a difficult problem to solve with compassion,<br />

less salutary “solutions” may present themselves. While<br />

none of the activists who push for access to physician-assisted<br />

suicide like to focus on the financial benefits, governments<br />

facing entitlement spending challenges may see a certain<br />

allure in being able to terminate an elderly citizen’s claims on<br />

medical spending under the false flag of “compassion.”<br />

<strong>March</strong> <strong>22</strong>, <strong>2024</strong> • ANGELUS • 23