Reflections of the Buddha - The Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts

Reflections of the Buddha - The Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts

Reflections of the Buddha - The Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

such quintessential virtues as compassion and wisdom in<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir images <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>s and bodhisattvas. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

sculptures in <strong>the</strong> exhibition once stood as “living” sculptures<br />

on altars and in sanctuaries throughout Asia. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were enshrined icons that were consecrated in rites that<br />

brought images “to life.” Clerics would invite <strong>the</strong><br />

appropriate deity’s energy to reside in <strong>the</strong> image and<br />

blessed it in such a way that <strong>the</strong> image could serve as<br />

an adequate symbol <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> deity depicted. Several <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> larger works in <strong>the</strong> exhibition, such as Standing<br />

<strong>Buddha</strong> Śākyamuni (no. 9 in <strong>the</strong> checklist that follows this<br />

essay) from late sixth-century China and Standing <strong>Buddha</strong><br />

Amitābha (no. 3) from mid-thirteenth century Japan, were<br />

probably consecrated in this way and thus served to establish<br />

a bond between <strong>the</strong> enlivened deity and <strong>the</strong><br />

believers who prayed be<strong>for</strong>e it. This required <strong>the</strong> proper<br />

attitude <strong>of</strong> humble acknowledgement <strong>of</strong> one’s personal<br />

need <strong>for</strong> spiritual aid and <strong>the</strong> recognition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior<br />

wisdom and compassion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>s and bodhisattvas<br />

embodied in <strong>the</strong> icons.<br />

Like some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r Buddhist sculptures<br />

in this exhibition, <strong>the</strong> white marble Standing <strong>Buddha</strong><br />

Śākyamuni incorporates <strong>the</strong> image <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lotus, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

most popular metaphors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Buddhist journey to<br />

awakening: <strong>The</strong> plant’s seed is nourished in <strong>the</strong> mud <strong>of</strong><br />

samsāra only to rise above <strong>the</strong> waterline to bloom untainted<br />

in <strong>the</strong> pure sunshine <strong>of</strong> Nirvāna. To emphasize<br />

this journey, <strong>the</strong> artist sculpted a stylized lotus bud<br />

between <strong>the</strong> feet and an honorific tassel in <strong>the</strong> shape<br />

<strong>of</strong> a lotus blossom near <strong>the</strong> proper left shoulder <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Buddha</strong>. At <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pulitzer</strong>, this journey from samsāra to<br />

Nirvāna is accentuated through <strong>the</strong> sculpture’s placement.<br />

It stands at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> light-filled main gallery,<br />

next to a water garden filled with small dark rocks that<br />

make <strong>the</strong> water look blackish, like <strong>the</strong> mud in which <strong>the</strong><br />

lotus grows. <strong>The</strong> combination <strong>of</strong> natural light reflected<br />

<strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> water and Ellsworth Kelly’s Blue Black (no. 18) on<br />

<strong>the</strong> wall behind it makes <strong>the</strong> white marble appear luminous,<br />

beckoning <strong>the</strong> visitor to move down <strong>the</strong> long<br />

narrow gallery to meet it.<br />

Standing <strong>Buddha</strong> Śākyamuni rewards <strong>the</strong> visitor<br />

with its beautifully carved details and juxtapositions: a<br />

monk’s robe rendered with fan-like folds that descend dynamically<br />

across <strong>the</strong> body contrasts with <strong>the</strong> still,<br />

symmetrical face that looks down with half-opened eyes<br />

in a meditative state. Meditation, which involves learning<br />

various types and levels <strong>of</strong> concentration, stills <strong>the</strong> mind<br />

and is a precondition <strong>for</strong> practitioners to understand and<br />

experience <strong>the</strong> teachings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>. Artists depicting<br />

<strong>Buddha</strong>s in meditative states sought to render <strong>the</strong>m with<br />

expressions <strong>of</strong> mindful composure and serenity that transcend<br />

all physical discom<strong>for</strong>ts and psychological<br />

emotions, including joy and sorrow.<br />

Not only do <strong>the</strong> works in <strong>the</strong> exhibition exemplify<br />

such Buddhist teachings and practices, but each was<br />

also part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fluid exchanges between monastic and<br />

lay communities from different parts <strong>of</strong> Asia that wove<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r seemingly disparate traditions and gave rise to<br />

8<br />

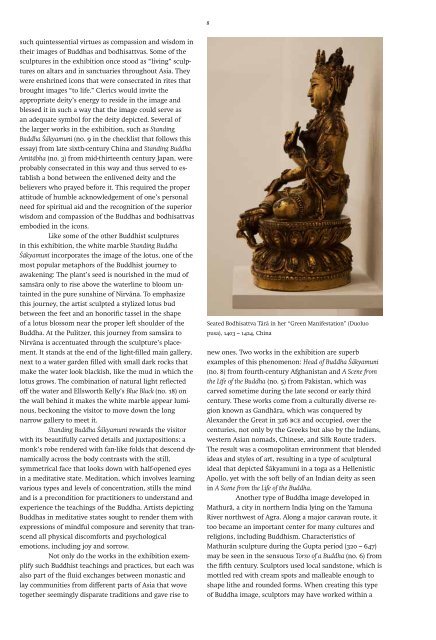

Seated Bodhisattva Tārā in her “Green Manifestation” (Duoluo<br />

pusa), 1403 – 1424, China<br />

new ones. Two works in <strong>the</strong> exhibition are superb<br />

examples <strong>of</strong> this phenomenon: Head <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong> Śākyamuni<br />

(no. 8) from fourth-century Afghanistan and A Scene from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Life <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong> (no. 5) from Pakistan, which was<br />

carved sometime during <strong>the</strong> late second or early third<br />

century. <strong>The</strong>se works come from a culturally diverse region<br />

known as Gandhāra, which was conquered by<br />

Alexander <strong>the</strong> Great in 326 bce and occupied, over <strong>the</strong><br />

centuries, not only by <strong>the</strong> Greeks but also by <strong>the</strong> Indians,<br />

western Asian nomads, Chinese, and Silk Route traders.<br />

<strong>The</strong> result was a cosmopolitan environment that blended<br />

ideas and styles <strong>of</strong> art, resulting in a type <strong>of</strong> sculptural<br />

ideal that depicted Śākyamuni in a toga as a Hellenistic<br />

Apollo, yet with <strong>the</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t belly <strong>of</strong> an Indian deity as seen<br />

in A Scene from <strong>the</strong> Life <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r type <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong> image developed in<br />

Mathurā, a city in nor<strong>the</strong>rn India lying on <strong>the</strong> Yamuna<br />

River northwest <strong>of</strong> Agra. Along a major caravan route, it<br />

too became an important center <strong>for</strong> many cultures and<br />

religions, including Buddhism. Characteristics <strong>of</strong><br />

Mathurān sculpture during <strong>the</strong> Gupta period (320 – 647)<br />

may be seen in <strong>the</strong> sensuous Torso <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Buddha</strong> (no. 6) from<br />

<strong>the</strong> fifth century. Sculptors used local sandstone, which is<br />

mottled red with cream spots and malleable enough to<br />

shape li<strong>the</strong> and rounded <strong>for</strong>ms. When creating this type<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong> image, sculptors may have worked within a