An IntervIew wIth PAtrIck Bellew, AtelIer ten - BetterBricks

An IntervIew wIth PAtrIck Bellew, AtelIer ten - BetterBricks

An IntervIew wIth PAtrIck Bellew, AtelIer ten - BetterBricks

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

them to understand the consequences of their decisions, and start to move towards making better buildings. For the<br />

most part however, the collaborative relationship within design teams, whether it be architects or structural engineers,<br />

has been exciting and for the most part fruitful.<br />

“In the earlier part of<br />

my career, we used<br />

to do what we called<br />

“stealth” engineering...<br />

The minute that you put<br />

it up as an additional<br />

item in the “green<br />

column” of the analysis,<br />

it is then a hostage to<br />

fortune and to budget<br />

cuts, whereas we would<br />

rather see it as being<br />

an intrinsic part of a<br />

good building.”<br />

Nonetheless, a realistic look back at many of our projects would suggest that<br />

most clients prepare a little bit in their ambitions, but moving them to more<br />

innovative environmental ideas still remains extremely difficult. I do think that<br />

sometimes we over analyze the things that we are doing.<br />

In the earlier part of my career, we used to do what we called “stealth” engineering<br />

where we would simply install something, such as heat recovery, as standard on all<br />

the ventilation systems in the building, having satisfied ourselves that the energy<br />

efficiency gained was worth having. We wouldn’t necessarily do the detailed<br />

life cycle cost analysis to show that the client would realize a benefit over the<br />

long term, because we knew it would be so. The minute that you put it up as<br />

an additional item in the “green column” of the analysis, it is then a hostage to<br />

fortune and to budget cuts, whereas we would rather see it as being an intrinsic<br />

part of a good building. So these days, we do a combination of things that we<br />

just do as standard, and we then look for areas where we can “push the boat<br />

out” to make for buildings that move the debate about green design forward.<br />

<strong>BetterBricks</strong>: Are you familiar with the AIA’s 2030 Challenge? How would you characterize the best approach or strategies<br />

to get to net-zero carbon buildings?<br />

<strong>Bellew</strong>: I have some knowledge of the AIA’s 2030 Challenge documentation, and I think that it contains a very strong<br />

message. In the UK, our government is looking to mandate a more ambitious timeline to carbon neutral buildings, aiming<br />

for the domestic sector to be carbon neutral by 2016 and the commercial sector to be carbon neutral by 2019.<br />

There is some debate about the meaning of carbon neutral, and a particular debate is developing about the fact that<br />

the carbon neutrality of the project is in<strong>ten</strong>ded to be established without the ability to import energy from green sources<br />

offsite, or by using certified renewable energy credits. As you can imagine, this makes life rather challenging! There<br />

is also some debate about the definition of zero carbon and the tax breaks that are being allocated to zero carbon<br />

buildings; one supposes the treasury tries to make it difficult to achieve them in order to minimize the number of tax<br />

concessions they have to give!<br />

I wouldn’t take issue with any of the points raised in the 2030 Challenge headlines, except to highlight that one thing<br />

we are very interested in looking into is how we can make the construction of new buildings somehow link to the energy<br />

reduction in the existing building stock. To me it always seems crazy to spend a million dollars on a photovoltaic array<br />

to take a building from a 60% carbon reduction to a 64% carbon reduction, when<br />

the same amount of carbon could be saved by spending $250,000 on an adjoining<br />

building or nearby housing estate. How do we put in place mechanisms to allow<br />

the money to flow from one sector to another, and avoid wasting the green dollar<br />

on uneconomic renewable energy systems, when there are much softer targets<br />

nearby? I know this is a really difficult problem to solve, but it seems to me to be<br />

one that our legislature needs to get its head around in order to allow it to become<br />

part of the planning system.<br />

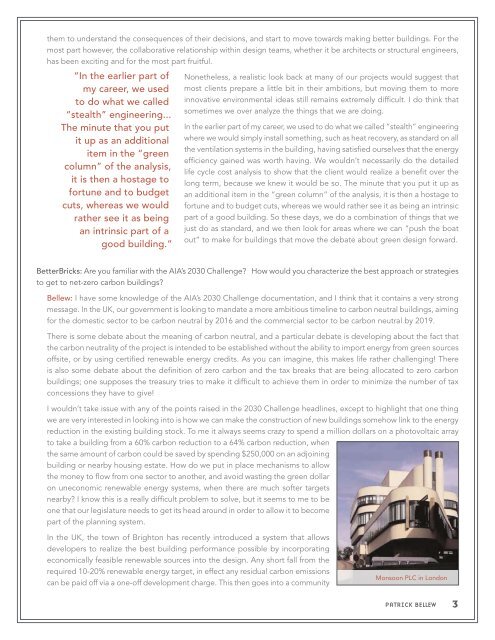

In the UK, the town of Brighton has recently introduced a system that allows<br />

developers to realize the best building performance possible by incorporating<br />

economically feasible renewable sources into the design. <strong>An</strong>y short fall from the<br />

required 10-20% renewable energy target, in effect any residual carbon emissions<br />

can be paid off via a one-off development charge. This then goes into a community<br />

Monsoon PLC in London<br />

Patrick <strong>Bellew</strong><br />

3