changing the course of stroke - New Jersey Medical School ...

changing the course of stroke - New Jersey Medical School ...

changing the course of stroke - New Jersey Medical School ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The surgery itself, and <strong>the</strong> approach into <strong>the</strong> skull, are used<br />

for a variety <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r problems. Kwartler, one <strong>of</strong> only a few<br />

physicians in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Jersey</strong> who perform this procedure, explains<br />

that a small area <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> head behind <strong>the</strong> ear is shaved and a<br />

curved incision about six to eight centimeters, or three and a<br />

half inches, in length is made to expose <strong>the</strong> mastoid. This bone<br />

behind <strong>the</strong> ear is hollow, like a corrogated cardboard box, and<br />

after <strong>the</strong> top to <strong>the</strong> box is taken <strong>of</strong>f, Kwartler and his team go<br />

deeper. Along <strong>the</strong> way, <strong>the</strong>y identify structures like <strong>the</strong> sigmoid<br />

sinus, <strong>the</strong> vein that drains blood out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> head, <strong>the</strong> lining <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> brain which is just to <strong>the</strong> north <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mastoid cavity, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> floor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> temporal lobe where balance canals sit. During<br />

surgery, “you can see <strong>the</strong>m, as well as <strong>the</strong> nerve which is responsible<br />

for movement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> face and cheek sensations. Once we<br />

have identified <strong>the</strong>se structures, we know we are in <strong>the</strong> right<br />

spot. We can see <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cochlea, an area called <strong>the</strong> round<br />

window, through which <strong>the</strong> sealed membrane <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cochlea can<br />

be entered.”<br />

After carving a little seat for <strong>the</strong> tiny receiver into <strong>the</strong> mastoid<br />

bone and making a tiny—about a millimeter in size—<br />

opening into <strong>the</strong> basal, or first, turn <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> spiral cochlea,<br />

Kwartler slides <strong>the</strong> electrode into this snail-shape structure.<br />

Then, “you’re done,” he says. “Just coil it down and close up.”<br />

Though dizzy and in some pain, Mink was in <strong>the</strong> recovery<br />

area by 11 am and back home by 5 pm with a little help from<br />

her children. She stayed close to bed all weekend with her “head<br />

bandaged and wrapped in a turban. I don’t like to be on<br />

painkillers and I remember being in tears at one point. I had no<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> balance.” Her instructions were to drink fluids, take<br />

Tylenol and not wash her hair. As Kwartler explains, “There is<br />

nothing we would be doing in <strong>the</strong> hospital except mo<strong>the</strong>ring<br />

her and a patient can get better mo<strong>the</strong>ring at home.”<br />

By Sunday, Mink felt a little better. Then, energized and anx-<br />

30<br />

PULSE SPRING 2003<br />

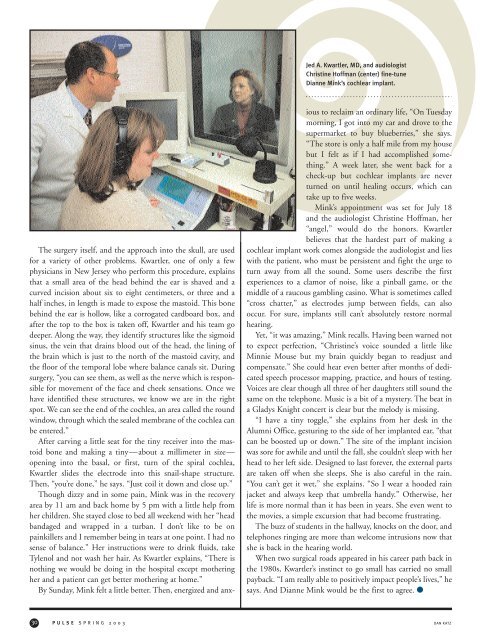

Jed A. Kwartler, MD, and audiologist<br />

Christine H<strong>of</strong>fman (center) fine-tune<br />

Dianne Mink’s cochlear implant.<br />

ious to reclaim an ordinary life, “On Tuesday<br />

morning, I got into my car and drove to <strong>the</strong><br />

supermarket to buy blueberries,” she says.<br />

“The store is only a half mile from my house<br />

but I felt as if I had accomplished something.”<br />

A week later, she went back for a<br />

check-up but cochlear implants are never<br />

turned on until healing occurs, which can<br />

take up to five weeks.<br />

Mink’s appointment was set for July 18<br />

and <strong>the</strong> audiologist Christine H<strong>of</strong>fman, her<br />

“angel,” would do <strong>the</strong> honors. Kwartler<br />

believes that <strong>the</strong> hardest part <strong>of</strong> making a<br />

cochlear implant work comes alongside <strong>the</strong> audiologist and lies<br />

with <strong>the</strong> patient, who must be persistent and fight <strong>the</strong> urge to<br />

turn away from all <strong>the</strong> sound. Some users describe <strong>the</strong> first<br />

experiences to a clamor <strong>of</strong> noise, like a pinball game, or <strong>the</strong><br />

middle <strong>of</strong> a raucous gambling casino. What is sometimes called<br />

“cross chatter,” as electrodes jump between fields, can also<br />

occur. For sure, implants still can’t absolutely restore normal<br />

hearing.<br />

Yet, “it was amazing,” Mink recalls. Having been warned not<br />

to expect perfection, “Christine’s voice sounded a little like<br />

Minnie Mouse but my brain quickly began to readjust and<br />

compensate.” She could hear even better after months <strong>of</strong> dedicated<br />

speech processor mapping, practice, and hours <strong>of</strong> testing.<br />

Voices are clear though all three <strong>of</strong> her daughters still sound <strong>the</strong><br />

same on <strong>the</strong> telephone. Music is a bit <strong>of</strong> a mystery. The beat in<br />

a Gladys Knight concert is clear but <strong>the</strong> melody is missing.<br />

“I have a tiny toggle,” she explains from her desk in <strong>the</strong><br />

Alumni Office, gesturing to <strong>the</strong> side <strong>of</strong> her implanted ear, “that<br />

can be boosted up or down.” The site <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> implant incision<br />

was sore for awhile and until <strong>the</strong> fall, she couldn’t sleep with her<br />

head to her left side. Designed to last forever, <strong>the</strong> external parts<br />

are taken <strong>of</strong>f when she sleeps. She is also careful in <strong>the</strong> rain.<br />

“You can’t get it wet,” she explains. “So I wear a hooded rain<br />

jacket and always keep that umbrella handy.” O<strong>the</strong>rwise, her<br />

life is more normal than it has been in years. She even went to<br />

<strong>the</strong> movies, a simple excursion that had become frustrating.<br />

The buzz <strong>of</strong> students in <strong>the</strong> hallway, knocks on <strong>the</strong> door, and<br />

telephones ringing are more than welcome intrusions now that<br />

she is back in <strong>the</strong> hearing world.<br />

When two surgical roads appeared in his career path back in<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1980s, Kwartler’s instinct to go small has carried no small<br />

payback. “I am really able to positively impact people’s lives,” he<br />

says. And Dianne Mink would be <strong>the</strong> first to agree. ●<br />

DAN KATZ