A NEW WAY OF AUDITING – AUDIT IN KNOWLEADGE BASED ...

A NEW WAY OF AUDITING – AUDIT IN KNOWLEADGE BASED ...

A NEW WAY OF AUDITING – AUDIT IN KNOWLEADGE BASED ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

A <strong>NEW</strong> <strong>WAY</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong><strong>AUDIT</strong><strong>IN</strong>G</strong> <strong>–</strong> <strong>AUDIT</strong> <strong>IN</strong> <strong>KNOWLEADGE</strong> <strong>BASED</strong><br />

SOCIETY<br />

Radneantu Nicoleta, asist. univ.drd, Universitatea Romano-Americana<br />

Cruceru Anca, prep. univ.drd, Universitatea Romano-Americana<br />

ABSTRACT:<br />

The modern world is under going a fundamental transformation characterized by a lot of challenges, dynamism,<br />

globalization, and the increasing influence of Information and Communication Technologies. The particular<br />

importance, proved by the informatics and communication technology in all fields of economical and financial<br />

activities, has also occurred, within the informatics system environments, as a permanent companion of the<br />

accounting and audit from almost all entities. Passing towards the market economy has determined the<br />

importance increase of the audit activity and the introduction of new rules, methodologies and procedures<br />

adapted to the needs of economical reality and to the fiscal system generated by them.<br />

1. Introduction<br />

In the last decades we have noticed a lot of phenomena and processes which<br />

characterize the human society evolution on its whole and which indicate the fact that we are<br />

in the middle of a profound transformation period, transformations that define the transition<br />

from the industrial society to a new type of society <strong>–</strong> the society based on knowledge.<br />

Passing towards the market economy has determined the importance increase of audit<br />

activity and the introduction of new rules, methodologies and procedures adapted to the<br />

needs of economical reality and to the fiscal system generated by them.The company success<br />

does not depend any more on the production facilities, on the financial capital and on the<br />

properties, but it more and more depends on the immaterial values. The capacity essence of a<br />

person, an enterprise or an entire society, to yield wealth firstly consists of its specific<br />

knowledge. Referring to the role inversion of the two asset categories, material and<br />

immaterial, which has been realized and is amplified within the modern economy, A. Toffler<br />

stands: “what matters is not the buildings or the devices of a company, but the contracts and<br />

the power of marketing and of its sale force, the organizational capacity of the administration<br />

and the ideas that idle in the employees’ minds”.<br />

2. Changing at the level of auditing activity<br />

The increasing importance of the so-called knowledge economy, which is often<br />

associated with industries such as software, pharmaceuticals, the media, and financial<br />

services, will continue to change our image of the economy and of value creation. Factories<br />

and assembly lines will no longer form the wealth of a company; instead it will be the<br />

creativity and capacity for learning of the employees, innovation, and the ability to maintain<br />

long-term customer and business partner relationships.<br />

But there is no exclusive "either-or" between industrial and knowledge economy.<br />

Many products will continue to be manufactured industrially. However, the share of<br />

intellectual capital and therefore of intangible assets that flows into the development and<br />

design of new products and that forms the basis for modern competitive production and<br />

supply chain processes will increase. But to convert their knowledge capital into a<br />

measurable performance and results, companies require appropriate instruments for control.<br />

A combination of "old" and "new" is also valid here - for example, efficient cost<br />

management in combination with effective innovation, market, sales, and customer<br />

5

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

relationship management. Here we need to catch up, both with regard to business science and<br />

theory as well as the practical aspects.<br />

The value of these companies is mainly determined by the employees’ abilities in<br />

designing informatics programs, in the Internet use, by professional experience, by their<br />

cleverness and reputation. But the enterprise activity cannot be conceived without the clients’<br />

existence. Thus, elements related to its commercial aspect, as some good knowledge of the<br />

commodity market and of the clients, their loyalty, a good way of distribution, the marketing<br />

strategies, all contribute to the increase of the enterprise value. Through all these there will<br />

be reached the situation in which the market value of such a company is much higher than its<br />

accounting value. This tendency will be amplified in future and there could be a danger,<br />

namely the traditional financial situations would become, to a great extent, useless for the<br />

users of financial accounting information.<br />

The Office of the Auditor General promotes accountability and best practices in<br />

government operations. Methodology is how the Office codifies the standards and practices<br />

that are to be followed by auditors in carrying out their work. It is an inherent aspect of what<br />

we do, why we do it, and how we do it. It gives rigour and discipline to our work as well as<br />

provides the structure within which audit teams exercise professional judgment.<br />

Considerable effort has been put into updating our audit methodology in order to:<br />

• recognize the unique requirements of our different product-lines;<br />

• take advantage of the capability of electronic tools such as the Internet;<br />

• increase its usefulness to our practitioners<br />

The main feature of the audit process is the independence of the one that performs it:<br />

In all matters relatedto the audit, the IS (Informational System) auditor should be<br />

independent in both attitude and appearance. The independence of such an approach refers to<br />

the lack of any kind of restriction which could affect the checking purpose, efficiency and<br />

conclusions. The testing and the evaluation presuppose that the audit authority should firstly<br />

analyze the deeds, and after this express its independent opinion.<br />

By computer use, the audit approach is modified due to the new processing, storage<br />

and presentation modalities of the information given by the informatics applications, without<br />

changing the general objective and the audit purpose. The traditional procedures of data<br />

collecting and result interpretation are replaced, totally or partially, with informatics<br />

procedures.<br />

The existence of the informatics system can affect the internal audit systems used by<br />

the entity, the way of risk evaluation, the performance of audit tests and basic procedures<br />

used in order to achieve the audit objective.<br />

Audit is designed to determine whether financial statements are fairly presented in<br />

accordance with International Accounting Standards (IAS) or Generally Accepted<br />

Accounting Principles (GAAP). In the United States, audit is required for all publicly<br />

registered companies.<br />

In addition, audit may be performed for private companies, registered charities, and<br />

some governmental and public entities. Certain forms of private companies are required to<br />

have an external audit. Private companies typically request financial audits year after year<br />

because lenders may have required an audit or owners may want to have external unbiased<br />

eyes look at the financial statements to determine if the company is complying with all the<br />

required accounting principles. Charities would require a audit to show the financial status of<br />

the organization to potential donors. Governments and government businesses are usually<br />

required to be audited by statutes to determine if all the money budgeted has been properly<br />

spent. Government financial reports are not always audited by outside auditors. Some<br />

governments have elected or appointed auditors.<br />

Other than testing the reliablility of a firm's controls, audits can alert management to<br />

weaknesses in the firm's controls, as well as suggest operational improvements that could be<br />

6

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

undertaken. These are highlighted in the Management Letter from the auditors. Strategic<br />

systems auditors provide a top down approach to auditing by first examing a firm's business<br />

strategy and keys to competitive advantage.<br />

The development of an economy based on knowledge has led to the development of<br />

some new activities, as the electronic commerce (e-commerce), banking activities on Internet<br />

(e-banking), touristy activities on Internet, educational activities on Internet (e-learning) and<br />

the list could continue. This new development of informatics has led to the creation of some<br />

new economical activities (virtual enterprises), namely of some new economical activity<br />

categories which do not directly operate with physical products, but with virtual ones,<br />

through non-physical financing, but with physical results.<br />

The statistical data published by international institutions shows that the role of Small<br />

and Medium Enterprises in the economy is more and more important. This trend is not only<br />

determined by the SMEs characteristics, but also by the whole world economic environment<br />

evolutions. These two elements define SMEs as the main economic development determinant<br />

in the upcoming period. Romania’s integration in EU opens large development perspectives<br />

in all the sectors of the social-economic life. The Romanian companies, irrespective their size<br />

will be in an everlasting competition with those from EU. The competition will be also felt<br />

on all the markets approached by the Romanian companies. Like the SMEs from the EU<br />

member states, the SMEs have an important role in the Romanian economy.<br />

The introduction of the new technologies determines major changing in the audit<br />

activity flow, a series of laborious and manually difficult to achieve procedures being<br />

replaced by automatic procedures, and with the auditor’s activity changing the accent on the<br />

qualitative analysis part and on the result interpretation.<br />

Another challenge for the audit authority is the acknowledgement, the recording and<br />

the evaluation of the new assets within the non-corporeal immobilizations, such as: knowhow,<br />

the informatics programs, internet domains, etc, and also of the circulating assets (the<br />

relationships with clients and suppliers), the intellectual capital.<br />

The increase of the immaterial asset importance emphasizes the problems of the real<br />

taking-down in documents and the reflection, in the accounting, of the operations regarding<br />

this asset category. The actual accounting treatment of the immaterial, concerning the<br />

immediate passing to the period expenses, is always motivated by prudence. Prudence<br />

demands that the assets and the incomes should not be over-evaluated, and the debts and the<br />

expenses should not be under-evaluated. The procedures resulted from applying the prudence<br />

principle aims at moderating the board tendencies of presenting an as good as ossible<br />

company image. Even more, because the immaterial resource existence is difficult to be<br />

checked, they could be used in order to administrate or even manipulate the result.<br />

The reticence concerning the calculation of the intellectual capital value dimension is<br />

explained by the difficulty and the cost of existing measurement proceeding application, and<br />

of selecting the indicators that present the relevance managerially. In its turn, the reticence<br />

concerning the reporting of the existent intellectual capital measuring results devolves from<br />

the stressed relativism in the obtained value interpretation, from the risk of revealing<br />

company aspects of strictly internal importance, and from the lack of an established format of<br />

such reports.<br />

Up to present the companies have been owners or at least auditled anything they have<br />

considered affects the business. In future, the command and audit are more and more<br />

replaced by all kinds of relationships: alliances, mixed companies, partnerships, know-how,<br />

etc. Their strategies must be global at least regarding the technologies, the finance, the<br />

products and the markets. The focus on cost reduction and on profit could lead to the activity<br />

contraction, without the organization activity being improved.<br />

The future organization is characterized by responsibility, autonomy, risk and<br />

uncertainty. The chain services <strong>–</strong> advantages comes into new vision and approach. The new<br />

7

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

economy determines the change of the auditor’s status, namely from specialist to generalist<br />

(the specialization could disappear or the client could demand another type of service).<br />

Therefore, we notice a change, we can say a historical one, in which the virtual is equal to the<br />

real and even exceeds it.<br />

In such situations the audit must have in view the following aspects:<br />

− providing the adequate framework, based on informatics technology integration, so that<br />

the activities accomplished during the carrying on of the project should be in accordance to<br />

the<br />

objectives and terms of accomplishing, approved at institutional level at the project<br />

substantiation;<br />

− the accordance to the program demands;<br />

− the recording of some technical difficulties during the project;<br />

− the activity modernization as a result of the new technology implementation;<br />

− the technical solution reliability and the implementations of the system functioning on the<br />

increase of the activity quality;<br />

− the training degree of users, related to the need of achieving the performance level required<br />

by the new approach, analyzed from the point of view of the impact with the new<br />

technologies;<br />

− the existence and the observance of the standards regarding system security, as well the<br />

quality oftechnical and methodological support.<br />

An informatics environment could offer the auditors the possibility of additional<br />

processing, by providing the information solicited in formats requested by the auditor, in<br />

order to interpret or use them as input data for specialized programs of audit assisted by<br />

computer.<br />

As a management tool data audit work should help organizations make best use of<br />

data in order to obtain the necessary information, often through the development of an<br />

information strategy. Data audit as part of the information audits indirectly:<br />

- aid management decision making<br />

- support and encourage competitive advantage<br />

- enable organizations to adapt and change<br />

- facilitate organizational communication<br />

- encourage use of, and investment in, IT<br />

- contribute to the value of manufactured products<br />

In order to develop ah high quality audit, the auditor must know the main goals of the<br />

audited organization and to determine the concordance between realities and the<br />

expectations.<br />

3. Conclusion<br />

In the case of computerization of a significant part from the entity activity, there is<br />

necessary the evaluation of the informatics system usage influence upon the audit risks,<br />

having in view the aspects related to the test relevance and credibility. The informatics<br />

system complexity is granted by a series of relative features at: the transaction volume, the<br />

procedures of data validation or of data transfers among applications, automatic engendering<br />

of transactions, the communication with another applications or informatics systems, the<br />

complexity of calculation algorithms, the utilization of some information coming from<br />

external data sources without their validation.<br />

In the first step, characterized by the utilization of some informatics procedures<br />

complementary to the traditional procedures for a series of specific activities: the data<br />

collecting and proper processing, the documentation of audit tests, the result interpretation,<br />

the communication between auditors and the checked entity, there is noticed an evolution of<br />

8

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

motivation by accepting the new audit methods based on the use of informatics technology<br />

within the audit activity, by changing the auditors’ mentality, by the interest for providing the<br />

hardware, software and communication infrastructure, by the permanent training of the<br />

personnel, as well by the interest for developing some support applications for the audit<br />

activity.<br />

The natural evolution is towards the extension of the audit based on computer,<br />

through which a major part of the traditional routine procedures, time <strong>–</strong> intensive, having a<br />

high level of difficulty and which manipulate a large data volume, are substituted with<br />

specialized software programs, a solution that contributes to the increase of audit efficiency<br />

and quality.<br />

A perspective with a larger horizon is constituted by the implementation of on-line<br />

audit techniques which shall represent a qualitative step in audit performing through the<br />

transition from a lonely audit to a audit within network (in an environment based on<br />

computer networks: Internet, intranet).<br />

The main premise of such an approach is the technological feasibility: the accounting<br />

information registered and stored, in general, on an electronic support (or an alternative, but<br />

accessible environment). The implementation of the audit based on informatics technology<br />

usage signifies the implementation of a new working way, which presupposes the permanent<br />

auditor collaboration with the checked entities (central and local institutions and authorities,<br />

organizations and enterprises) under the conditions and according to the regulations<br />

associated to this system, in order to achieve the action convergence and the audit activity<br />

objectives. It is necessary that the new working way should provide coherence and<br />

concordance with the actual procedures, the problems tackled through informatics procedures<br />

constituting a dematerialized alternative of the existent traditional processes.<br />

Companies need management processes that permit quick and efficient exchange of<br />

knowledge between individual managers to ensure optimal usage of this information. Such<br />

processes include a strategic management process that establishes continuous, strategic<br />

dialog throughout the company and thus ensures that the company remains a nose ahead of<br />

external developments that could harm its intangible assets based competitive position.<br />

Companies must also have a process for performance management that optimizes the<br />

exploitation of existing assets in order to achieve short term income goals. Both processes<br />

need to be linked with each other to enable management to manage for growth and for short<br />

term results at the same time.<br />

From all those presented above there could be concluded that the modern technology<br />

integration represents an essential condition for increasing the efficiency of audit activity.<br />

The result of this integration should bring the auditors in an optimum position in order to take<br />

the pulse of an organization, under the conditions in which the planning, the proper testing<br />

and the reporting are performed in parallel and in real time.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. BANACU,C, 15/11/2006, Metode de evaluare a programelor de calculator, Bucuresti,<br />

Tribuna Economica<br />

2. BOULESCU, M, 2005, Auditul fiscal al agenŃilor economici, Bucuresti, Editura Tribuna<br />

Economica<br />

3. BusinessWeek (1999) <strong>–</strong> Knowledge markets. BusinesWeek Online, December 13, 1999<br />

4. http://www.businessweek.com/1999/99/99_50/b3659022htm.<br />

5. COLLASE, B., 2000, Encyclopédie de comptabilité, contrôle de gestion et audit, Paris,<br />

Economica<br />

9

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

6. FELEAGA N., MALCIU, L., 2002, Politici si optiuni contabile, Bucuresti, Editura<br />

Economica<br />

7. FELEAGA, N., IONASCU, I., 1999, Tratat de contabilitate financiara, vol. I-II, Bucuresti,<br />

Editura Economica<br />

9. FELEAGA, N., 2000, Sisteme contabile comparate, vol. II, Bucuresti, Editura Economica<br />

10. MUNTEANU, V, 2006, Audit si audit financiar-contabil, Bucuresti, Editura Sylvi<br />

11.NICOLESCU, O., NICOLESCU L,2005,Economia, firma si managementul bazate pe<br />

cunostinte, Bucuresti, Editura Economica<br />

12. POPEANGA, P, 2004, Auditul financiar si fiscal, Editura „C.E.C.C.A.R.”<br />

13.XXX- LEGE Nr. 84 din 18 martie 2003 pentru modificarea si completarea Ordonantei<br />

Gvernului nr. 119/1999 privind auditul public intern si auditul financiar preventiv<br />

14. http://www.crie.ro/<br />

10

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

THE ACCOUNT<strong>IN</strong>G AND FISCALITY <strong>OF</strong> PR<strong>OF</strong>IT REPARTITION<br />

Bengescu Marcela, conf. univ. dr.<br />

Drila Gherghina, lecturer univ. dr.<br />

Universitatea din Piteşti<br />

ABSTRACT: Cette étude se propose de réaliser une synthèse des dispositions législatives concernant la<br />

répartition du profit. La problématique abordée vise deux objectifs principaux : 1. les distributions provenant du<br />

profit brut ; 2. la répartition du profit net. Les aspects théoriques et méthodologiques ont été adaptés à la forme<br />

juridique d’organisation des entités économiques : 1. les sociétés nationales, les compagnies nationales et les<br />

sociétés commerciales d’État à capital intégral ou majoritaire, les régies autonomes ; les sociétés commerciales à<br />

capital majoritaire privé.<br />

L’étude veut souligner certains éléments de détail, tels que : la distinction entre la perte comptable et la<br />

perte fiscale ; les destinations du profit par rapport à la forme juridique d’organisation de l’entité économique, le<br />

traitement comptable et fiscal des répartitions provenant du profit.<br />

General Overview<br />

The result represents the indicator for evaluating the financial performance of the<br />

company, and is determined by subtracting the expenditure from the income of the ending<br />

year. Although it is presented as a global indicator in financial statements, it is determined<br />

monthly.<br />

Methodologically speaking, in order to calculate the result, the income and<br />

expenditure accounts have to be closed out.<br />

The image of the analyzed indicator is constructed from elements that comprise the<br />

results account, and also from those that refer to the changes of internal or external<br />

circumstances concerning the company.<br />

Companies have the tendency of modifying accounting practices and estimations in<br />

order to adapt to economic circumstances or in order to improve their image.<br />

Sometimes, retroactive modification of financial results questions the trust of the<br />

public interested in the company’s performance. IAS 8 states how annual accounts must be<br />

treated in order for the company to present its results on a coherent and permanent basis.<br />

All income and expenditure noticed in the financial year must be taken into<br />

consideration upon the calculation of the net result of the respective year, apart from the<br />

situation in which another international accounting regulation authorizes a different<br />

procession.<br />

Extraordinary elements and the effects of change in accounting estimations are part of<br />

the elements included in the net result.<br />

In certain circumstances, some elements can be excluded from the net result of the<br />

current period. IAS 8 mentions two of these circumstances: the correction of fundamental<br />

errors and the effect of changing the accounting methods 1 .<br />

11

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

In accordance with those presented above, the Romanian accounting legislation states that:<br />

“In case of correcting errors that generate reported accounting loss, this must be covered<br />

before distributing profit. In the notes to the financial statements additional information must<br />

be provided regarding the errors that were noticed” 2 .<br />

Legal Provisions regarding Profit Distribution<br />

The dividends that are distributed to shareholders, proposed or declared after the 31 st<br />

of December, as well as other similar distributions made from the profit mass, must not be<br />

acknowledged as debt at the conclusion of the financial year.<br />

The distribution of the profit is recorded in accounting based on destinations, after the<br />

approval of annual financial statements. Profit distribution is performed in accordance with<br />

valid legal provisions.<br />

Amounts that represent reserves established out of the profit of the current financial<br />

year, based on some legal provisions, is recorded through the use of accounting article<br />

129=106. The accounting profit that is left subsequent to this distribution, are transferred to<br />

account 117, from where it is going to be distributed to its other legal destinations.<br />

The reported accounting loss is covered by the profit of the current financial year and<br />

the reported profit, by reserves and by the equity, according to the decision of the<br />

shareholders’ or associates’ general assembly, with the observance of legal provisions.<br />

Distributing the Gross Profit<br />

As regards the distribution of the gross profit, we take into consideration the following<br />

situations: setting up the legal reserve , covering the fiscal loss of the previous years and<br />

setting up other reserves equal to the amounts generated by the fiscal facilities stipulated by<br />

the norms regarding profit imposition.<br />

Regarding the legal reserves, the Fiscal Code, in art. 22, states dispositions regarding<br />

the limits of fiscal deductibility: „the legal reserve is deductible within a limit of 5% applied<br />

to the accounting profit, before determining the profit tax, out of which the non-taxable<br />

income is subtracted and the expenditure corresponding to this income is added, until this<br />

reaches the fifth part of the subscribed and submitted equity or of the patrimony, as the case<br />

may be, according to the laws of organization and functioning”.<br />

Observation: According to these regulations, the legal reserve is established at a<br />

different level than that listed in the Law Regarding Commercial Companies no. 31/1990,<br />

republished. Also, there is a necessity to simultaneously meet two requirements:<br />

Requirement No. 1: Legal reserve = 5% (profit before taxation <strong>–</strong> non-taxable income +<br />

expenditure corresponding to non-taxable income).<br />

Requirement No. 2: Legal reserve ≤ 1/5 x subscribed and submitted equity.<br />

According to the methodological norms the reserve is calculated cumulatively from<br />

the beginning of the year and is deductible upon the calculation of the monthly or trimonthly,<br />

as the case may be. Also, revenue mentioned by art. 20 of the Fiscal Code is included in the<br />

category of non-taxable income that is subtracted in the formula for the calculation of the<br />

reserve, with the exception of those stated at letter e) of the same article. The reserves set up<br />

in that way are appended or diminished based on the level of the accounting profit within the<br />

period of calculation.<br />

Conclusion: The formula can be performed monthly or trimonthly.<br />

The amount set up at the level required by the Fiscal Code is subtracted from the taxable<br />

income mass.<br />

12

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

The profit of the current financial year is included among the sources for covering the<br />

accounting losses of previous years, within the limits established by decision of the<br />

shareholders’ or associates’ general assembly.<br />

Part of the gross profit is used only to compensate fiscal losses, at each deadline for<br />

profit tax payment 2 .<br />

In this case, distributing the profit represents a technical requirement in determining<br />

the fiscal result. An exception is represented by companies that have recovered fiscal losses<br />

out of legal reserves. According to current legislation, the re-establishment of the legal reserve<br />

will not be deducted from the taxable income mass 3 .<br />

Consequently, the legal reserve is re-established from the net profit subject to<br />

distribution.<br />

129 ”Profit Distribution” = % UGross profit<br />

1061 „Legal<br />

Reserves”<br />

1171 ”The reported<br />

result representing<br />

undistributed profit or<br />

uncovered loss”<br />

1068 ”Other<br />

reserves”<br />

13<br />

distributionsU<br />

5% x regulated base<br />

Fiscal loss<br />

Amounts generated by<br />

fiscal facilities<br />

After deducting the aforementioned amounts, the net profit is distributed by observing<br />

the path established by the law, for state enterprises, or by the shareholders’ or associates’<br />

general assembly, for public companies.<br />

Accounting Records Performed At the Balance Sheet Date<br />

In observance of legal regulations the order of profit distribution is followed by the<br />

respective destinations, as follows 3 :<br />

a. Covering accounting losses of previous years:<br />

129 ”Profit Distribution” = 1171 ”The reported<br />

result representing<br />

undistributed profit<br />

or uncovered loss”<br />

Accounting loss minus<br />

fiscal loss<br />

We assume that companies envisaged by the respective dispositions should deduct<br />

their fiscal losses from the taxable profit obtained in the next consecutive 5 years. For this<br />

reason, in the accounting formula above we could indicate an amount equivalent to the part<br />

exceeding the fiscal loss 4 . Under the assumption that the proposed evaluation is against legal<br />

provisions, the tax payer would owe the state budget a profit tax corresponding to the<br />

unreported fiscal losses. The consequences of such an approach have negative side effects<br />

over the financial stability of the company.<br />

b. Establishing other reserves, representing fiscal facilities granted by the law:<br />

129 ”Profit Distribution” = 1068 ”Other<br />

reserves”<br />

Amounts generated by<br />

fiscal facilities

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

c. A particular case is represented by the distribution of the amounts destined for the<br />

participation of employees in the profits. In case of economic agents with state owned equity,<br />

employees are granted amounts representing 10% of the net profit, without exceeding, for<br />

each employee, the level of an average monthly base salary for the company, in the respective<br />

financial year<br />

In this case, the new legal dispositions state the rule according to which „the employee<br />

participation is reflected in accounting by setting up a provision for risks and expenses equal<br />

to the estimated amounts representing the gross amounts to which the employees are entitled,<br />

as follows” 5 :<br />

6812 “Operational expenditure<br />

regarding provisions”<br />

= 1518 "Other<br />

Provisions”<br />

14<br />

10% x Net Profit<br />

d. After deducting the amounts corresponding to the destinations mentioned, the net<br />

profit that is obtained is recorded as follows:<br />

129 ”Profit Distribution” = 1171 ”The<br />

reported result<br />

representing<br />

undistributed<br />

profit or<br />

uncovered loss”<br />

Net profit subjected to<br />

distribution in the balance<br />

sheet approval meeting<br />

Accounting records performed after the approval of the balance sheet<br />

a. The net profit obtained by the state venture „The National Lottery” from the sports<br />

bets activity will be transferred to the Ministry of Youth and Sports for financing athletic<br />

activities, including the Romanian Olympic Committee and the Romanian Football<br />

Federation 6 :<br />

1171 ”The reported result<br />

representing undistributed profit or<br />

uncovered loss”<br />

b. Employee participation in the profits:<br />

b.1 In case of private equity economic agents:<br />

1171 ”The reported result<br />

representing undistributed profit or<br />

uncovered loss”<br />

= 447 ”Special<br />

funds <strong>–</strong><br />

assimilated fees<br />

and transfers”<br />

= 424 ”Premiums<br />

representing<br />

employee<br />

participation in<br />

the profit”<br />

Net profit from sports bets<br />

≤ 10% net profit subjected<br />

to actual distribution<br />

b.2 In case of economic agents with state owned equity:<br />

Liabilities towards employees corresponding to their participation in the profit will be<br />

recorded in accounting based on salary expenditure in the year following that in question and,<br />

at the same time, the provision that was set up will be recorded under income 5 .

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

c. a minimum 50% of transfers to the state budget or to the local budget:<br />

1171 ”The reported result<br />

representing undistributed profit or<br />

uncovered loss”<br />

= 446 ”Other<br />

assimilated taxes,<br />

fees and<br />

transfers”<br />

15<br />

≥ 50% net profit subjected<br />

to actual distribution<br />

d. a minimum of 50% dividends in case of national companies and commercial<br />

companies with partially or entirely state owned equity:<br />

1171 ”The reported result<br />

representing undistributed profit or<br />

uncovered loss”<br />

= 457 ”Payable<br />

dividends”<br />

≥ 50% net profit subjected<br />

to actual distribution<br />

e. the rate of manager participation in the profit, established proportionately with the<br />

degree of fulfilment of the objectives agreed upon in the management contract 7 .<br />

1171 ”The reported result<br />

representing undistributed profit or<br />

uncovered loss”<br />

= 462 ”Various<br />

creditors”<br />

Amount established<br />

proportionately with the<br />

degree of fulfilment of the<br />

objectives agreed upon in<br />

the management contract<br />

Note: Out of the manger’s participation rate in the company’s profit, 75% will be<br />

represented by distributed shares, for cash generated by this rate.<br />

f. the net profit remaining after establishing the amounts for the aforementioned<br />

destinations is distributed for the setting up of own financing sources:<br />

1171 ”The reported result<br />

representing undistributed profit or<br />

uncovered loss”<br />

= 1068 «Other<br />

reserves»<br />

Net profit subjected to<br />

actual distribution<br />

(dividends + employee<br />

participation in the profit)<br />

An actual case regulated by national legislation refers to setting up own sources of<br />

financing for projects that are cofinanced through external loans, as well as for setting up the<br />

sources necessary to reimburse the equity instalments, to pay the interest rates, the fees and<br />

other costs corresponding to these external loans. In the spirit of these regulations, own<br />

financing sources for foreign loan projects include the contribution of the Romanian party to<br />

the completion of the project, as well as the amounts necessary to pay taxes and fees within<br />

the country and the value of other local costs, which cannot be paid for from external loans.<br />

We assume that this disposition is meant to ensure that net benefits obtained from such<br />

contributions remain intangible until the end of the year, thus ensuring an efficient<br />

management of economic resources.<br />

Legal and fiscal aspects regarding dividend distribution<br />

Regardless of ownership structure, dividends are distributed in relation to subscribed<br />

shares, if the constitutive act does not specify otherwise. They are paid at the date established<br />

by the shareholders’ or associates’ general assembly or, if so be the case, established by

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

special laws, but no later than 6 months of the approval of the annual financial statement of<br />

the concluded financial year. Otherwise, the company will pay penalties for the delay, equal<br />

to the legal interest rate, if the constitutive act or the decision of the shareholders’ general<br />

assembly which approved the financial statement corresponding to the concluded financial<br />

year did not establish a higher interest. 8<br />

Dividends are taxable with a rate of 16%. Income payers under the regime of payment<br />

at the source have the obligation to file form 205 ”Informative declaration regarding tax<br />

withheld for income under the regime of withholding at the source, on income beneficiary<br />

structure”, code 14.13.01.13/l. In case of dividend tax, declaration 205 should be filed until<br />

the 30th of June of the current year, for income paid in the previous financial year.<br />

.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

1. van Greuning H., International Financial Reporting Standards<strong>–</strong> A Practical Guide,<br />

IRECSON Publishing House, Bucharest 2005<br />

2. Ministry of Public Finance Order No. 1,752 of November 17 205 for the approval of<br />

accounting regulations compliant with European directives (M.O. no. 1,080 bis/11.30.<br />

2005).<br />

3. Law no. 571 of December 2003 regarding the Fiscal Code with all the modifications<br />

brought by Law no. 343 of July 17 2006 for the modification and completion of Law<br />

no. 571/2003 regarding the Fiscal Code (M.O. no. 662/08.01. 2006).<br />

4. Bengescu, M., Studiu comparat al normelor contabile privind cheltuielile şi veniturile<br />

întreprinderii, Agir Publishing House, Bucharest, 2006.<br />

5. Ministry of Public Finance Order No. 418/ 4.06.2005 regarding certain accounting<br />

observations applicable to economic agents, published in Romania’s Official Monitor,<br />

Part I, no. 310 of April 13 2005.<br />

6. Government Urgent Order regarding the distribution of the profit of the<br />

”Administration of the State Protocol Patrimony” state enterprise no.91, published in<br />

Romania’s Official Monitor, Part I, no. 277 of June 17 1999, art. 2.<br />

7. Government Urgent Order No. 39 of July 10 1997 regarding the modification and<br />

completion of the Law of the management contract no. 66/1993 (M.O. no. 151/07.11.<br />

1997.<br />

8. Law no. 441 of November 27 2006 for the modification and completion of Law no.<br />

31/1190 regarding commercial companies, republished and of Law no.26/1990<br />

regarding the registry of commerce, republished (M.O. no. 955/11.28.2006).<br />

16

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

ACCOUNT<strong>IN</strong>G HARMONIZATION <strong>–</strong> <strong>IN</strong> THE GLOBALIZATION<br />

PROCESS <strong>OF</strong> NATIONAL ECONOMY<br />

Dorel Mateş, Prof. univ. dr., West University of Timişoara,<br />

Faculty of Economic Science, J.H. PESTALOZZI,<br />

Veronica Grosu , Asist. univ. drd .<br />

„Ştefan cel Mare ” University of Suceava,<br />

Faculty of Economic Science and Public Administration,<br />

Marian Socoliuc , Prep. univ.<br />

„Ştefan cel Mare ” University of Suceava,<br />

Faculty of Economic Science and Public Administration,<br />

Abstract : On peut dire que la globalisation comptable est déjà une realité, les principes comptables<br />

nationales ayant substitué par une série de standards et normes reconnues au niveau international.<br />

L'Union Europèene suive l'harmonisation de l'information financière des societés coteés à la bourse,<br />

pour protéger et tuteller les investiteurs. Par l'application des principes comptables internationales IAS/IFRS on<br />

essaye de gagner de confiance dans les marchées financières, en facilitant les négociations transfrontalières et<br />

internationales des valeurs immobilières.<br />

L'importance de cette demarche <strong>–</strong> le passage des principes nationals envers des principes internationals,<br />

représentera une période délicate une modernisation inevitable, ainsi que beacoup des aspects legislatifs<br />

concernant l'organisation et le fonctionnement des entités économiques, les principes generales et les normes<br />

comptables nationales souffriront ou ont déjà souffert des transformations importantes.<br />

The globalization of the accounting process has already become reality, and the<br />

national accounting principles are being progressively substituted for international recognized<br />

rules and standards. The European Union is looking for a harmonization within the financial<br />

informational support of the companies enlisted on the stock exchange market, in order to<br />

create a safer environment for the investors. By applying the international accounting<br />

standards IAS/IFRS, one tries to give credit to the financial markets, and at the same time,<br />

tries to ease the international transactions of the stocks.<br />

The evolution from national regulations to international standards is in fact a delicate<br />

step determined by the inevitable upgrading of the legislation regarding the organization and<br />

functioning of the economic entities, and of the general principles and national accounting<br />

standards (the company law, fiscal code, accounting law).<br />

Adopting the International Accounting Standards by the IASB (International<br />

Accounting Standard Board) together with the IAS/IFRS standards, determined an<br />

irreversible progress by defining progressively the time and functioning conditions of an<br />

accountancy common language in Europe. Starting with the 1 st of January 2005, rule nr.<br />

1606/2002 (CE) given by the European Parliament and the Council from 19 th of July 2002,<br />

regarding the applying of international accounting standards, requires all European companies<br />

enlisted on the stock exchange market to draw up a consolidated balance sheet, according to<br />

the International Accounting Standards elaborated by the IASB. The member states accepted<br />

17

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

the notification of the European Commission, and pointed out, that the comparability of the<br />

balance sheets of the stock exchange enlisted companies, financial and insurance companies,<br />

builds up an essential factor for the integration of the financial markets. In addition, the<br />

interested companies have appreciated the adoption of the new International Accounting<br />

Standards IAS/IFRS as a positive step, because it would facilitate the trade with stocks,<br />

fusions and international procurements, as well as with financing operations.<br />

According to these regulations, the International Accounting Standards must be first<br />

approved, in order to check the comparability with the Accounting Community laws. On this<br />

purpose, a mechanism which will approve every standard has been created and activated, but<br />

it will be able to fulfill its amendments only after EFRAG (European Financial Reporting<br />

Advisory Group) and ARC (Accounting Regulative Committee), or the European<br />

Commission will approve its actions. These approved standards are being promulgated with<br />

the Rules, and then published in the EU Official Gazette GUUE, in every official language of<br />

the EU. Art. 5 of the Regulation No. 1606/2002/(CE) consented the member states to approve<br />

or to prescribe the adoption of the International Accounting Standards even after the stock<br />

exchange enlisted companies and the unlisted companies draw up their individual balance<br />

sheets. In other words, this regulation assures that the following categories of companies will<br />

adopt the IAS:<br />

- companies enlisted at the stock exchange market: must draw up an accrual balance<br />

sheet<br />

- companies that issue financial instruments: must draw up a balance sheet<br />

- Banks and financial institutions: must draw up an accrual balance sheet and a<br />

consolidated balance sheet, only if they are enlisted on the stock exchange market<br />

and haven’t drawn up yet a consolidated balance sheet.<br />

The Regulation foresees that the unlisted companies, which do not adopt internal rules<br />

(Civil Code, national accounting standards) can optionally adopt the IAS, and the companies<br />

that can draw up their balance sheet in a simplified form (abridged) according to the national<br />

accountancy legislation, are no longer compelled to adopt the IAS.<br />

As an example, starting with 2005, one can say that in Romania there are 2 categories of<br />

companies which draw up accrual and consolidated balance sheets, using 2 different and<br />

alternative accounting systems, which will probably coexist only for a limited period of time.<br />

1. The accounting system based on the International Accounting Standards of the IASB and<br />

adopted by the European Union, after their approval according to the mechanism described<br />

earlier.<br />

2. The accounting system based on the national regulations, approved by the OMFP<br />

1752/2005, modified and reedited accounting law 82/1991, modified and reedited company<br />

law.<br />

The authority in charge with the creation of the International Accounting Standards<br />

IAS/IFRS is IASB (International Accounting Standard Board), institution which was founded<br />

on 1st of April 2001, as a newer form of the IASC (International Accounting Standard<br />

Committee). IASC was founded in 1973 by the Federation of Accountants (IFAC), institution<br />

which represents the international profession of accounting, and it was created to promote the<br />

harmonization of the rules regarding how the economic entities draw up their balance sheets.<br />

Among the priorities of IFAC, the accounting harmonization objective should have<br />

been achieved by editing the international accounting standards, named IAS (International<br />

Accounting Standard), which will be used by the councils authorized to elaborate these<br />

standards in the IFAC member states. As for the IASC activity <strong>–</strong> the accounting standards<br />

which have been created in the beginning, gathered the accounting rules of the developed<br />

countries or the countries with an accounting tradition, especially the USA or the Anglo-<br />

Saxon countries, which already had criteria for relevating the assets, liabilities, expenditure<br />

and revenue, criteria which are very different from one another. Therefore, these accounting<br />

18

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

criteria could not establish a solid base for elaborating accounting standards from the IFAC<br />

member states; standards which should have substitute the national accounting standards of a<br />

country. For this reason, during the years 1999 and 2000 IASC initiated an updating process<br />

of the existent IAS accounting standards, in order to create a complete set of standards.<br />

Reviewing the IAS during the 90’s<br />

In 1989, the FRAMEWORK for the Preparation of Financial Statements had been published.<br />

It defines the informational objectives of the companies, showing the basic features of the<br />

balance sheet, gives the definition of the assets and liabilities of the patrimony, revenues and<br />

expenditures, also specifying the general principles of their accounting entry. This document<br />

also generates a theoretical support for the existent IAS, promoting the international<br />

accounting profession, the users, auditors and the countries, which want to adopt the IAS, to<br />

accept the IAS.<br />

In 1989 IASC started a revision process of the existent accounting systems; in order to<br />

improve their quality, reduce the number of rules, and to show the assets, liabilities, revenues<br />

and expenditures in a clearer way. Basically, the existence of different accounting systems,<br />

which are acceptable from a theoretical point of view, together with the accounting entry of<br />

the elements of patrimony, revenue increases or decreases, diminishes the comparability of<br />

the balance sheets, up to the inefficiency of the generated information.<br />

In 1993, the reviewing of the existent IAS determines the publication of 10 new<br />

accounting standards. Finally in year 1995, IASC sets up an agreement with IOSCO<br />

(International Organization of Securities Commissions) <strong>–</strong> organization which represents the<br />

commissions which supervise the world stock markets <strong>–</strong> regarding the integration of the<br />

necessary IAS standards, since IOSCO already approved for the cross border offerings<br />

balance sheet to be elaborated by the IAS standards.<br />

The reform in 2001<br />

During the first months of 2001, the revision and integration process of the existent<br />

IAS aimed the reform of IASC. Actually, the existent structure of IASC was being<br />

exclusively dependent on the international accounting profession <strong>–</strong> this was unfit to<br />

correspond with the IAS. The IASC Foundation was founded in March 2001, in Deloware<br />

USA, a non-profit and independent organization. SAC (Standards Advisory Council), IASB<br />

(International Accounting Standard Board) and SIC (Standing Interpretation Committee) are<br />

dependent on the IASC Foundation. This institution is being lead by a board of trusters,<br />

formed by 19 members, whose main function is to ensure the necessary financial support for<br />

the IASC. Basically, the IASC appoints the members of the SAC, IASB and SIC.<br />

Building up these institutions according to the IASC Constitution, ensures an adequate<br />

geographical representation for all the institutions that want clearer accounting standards: the<br />

international professional accountants, the financial investors and analysts, companies whose<br />

accounting systems are likely to be reformed, and finally, the auditors.<br />

The SAC Organization is built up by 45 professionals, from various countries, which have<br />

different technical background, and their position is to assist the IASB in determining the<br />

priority arguments in the process of elaboration and revision of accounting standards. IASB is<br />

formed by 14 international accounting experts. Their responsibility is to discuss and approve<br />

or disapprove of the international accounting standards and their interpretation.<br />

These processes are being organized by the IFRIC (International Financial Reporting<br />

interpretation Committee). After the IASC Foundation was created, and after the IASB<br />

members had been assigned, the newly elaborated accounting standards will be called IFRS,<br />

19

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

and they will gradually substitute the existent IAS. This action had been established at the<br />

first reunion of the IASB, to ensure permanent connection with IASC and IFAC.<br />

At the moment, the IAS accounting standards can be considered as a group of shared<br />

standards, approved, independent and complete. Therefore, one can understand why the<br />

European Commission chose to refer to the IAS in relation to how the balance sheets of the<br />

European economic entities had been elaborated and edited.<br />

On the other hand, the European Commission could have decided upon the elaboration of a<br />

set of accounting standards, which could have had determine an accounting harmonization<br />

within the EU market. At the same time, these accounting standards within a unique European<br />

context would have inevitably become different from the international accounting standards.<br />

This could have had excluded Europe from the international accounting harmonization<br />

process, even more, it could have blocked the possibilities of European companies to obtain<br />

resources from the global markets.<br />

Bibliography:<br />

1. Mateş D. , Matiş D,- Contabilitatea financiară a entităţilor economice, Editura Mirton ,<br />

Timişoara, 2006.<br />

2. Ristea M. - Contabilitatea financiară a întreprinderii, Editura Universitară, Bucureşti,<br />

2005.<br />

3. Gazeta Oficială a U.E nr. 392/2004.<br />

4. Gazeta Oficială a U.E nr. 299/2005.<br />

5. Regulamentul nr.1602/2002 al C.E.<br />

6. Regulamentul nr.1564/2005 al C.E<br />

20

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

PRESENT PRIORITIES <strong>IN</strong> THE BANK MANAGEMENT<br />

Avram Costin Daniel, Prep. univ. drd.<br />

University of Craiova<br />

ABSTRACT: The maturation of the Romanian bank management has happened on the background of<br />

the growing complexity of the banking activity, required by a competitive market, that have known a constant<br />

growth starting with the year 2000.<br />

The recent integration in the European Union has given much more courage to the foreign banks which<br />

regard Romania like a promising economic space. New challenges have appeared in these conditions for the<br />

bank management in our country, generated primarily by the obvious transformation in the bank’s culture.<br />

These developments have increased the need for the function of the risk measurement, management and<br />

control. The new banking environment and increased market volatility have necessitated an integrated approach<br />

to asset-liability and risk management techniques.<br />

The bank management in Romania is adapting constantly to the transformation of the<br />

business environment and of the legal frame regarding the organization and the management<br />

of the economical system in our country.<br />

These tendencies are visible at the top management level <strong>–</strong> banks’ leadership <strong>–</strong> as well<br />

as medium management level <strong>–</strong>leadership of the branches and offices of the central banks <strong>–</strong><br />

and they will continue to give shape to a new culture of the companies and to a active manner<br />

of approaching the specific market because “the gradual maturation of the bank system let to<br />

an increased complexity of the bank’s activity”[5].<br />

The majority of the analysis made over the present situation and the perspectives of<br />

the Romanian bank system are presented most often in a grey colored palette that is far away<br />

from anything that could bring optimism and trust to a clientele found already in difficulty. It<br />

is obvious that the prosperity of the economic agents is the one leading to the achieving of<br />

performances in a bank system and when the winners are awarded by the underground<br />

economy and corruption the banks’ role is dropping continuously in spite of all the protection<br />

the banking secret offers.<br />

The significant crisis the Romanian bank system has surpassed was provoked by<br />

external factors linked to the business environment that can let an important mark upon the<br />

functioning of the bank system but also by a series of internal factors that are related to a<br />

certain conservatism, to a lack of adaptability that prevented the surpassing of the<br />

protectionist mentality in favor of a market active mentality inside the bank system. “It has<br />

been said that risk in banks grows exponentially with the change rhythm but bankers do not<br />

adjust their perception on the risk as fast as they are expected to.<br />

From a practical point of view, this means the market’s capacity to innovate is grater<br />

than its capacity of understanding and adaptation to the afferent risks indifferent of the<br />

circumstances”[7].<br />

This study’s aim is to focus on the present tendencies of the bank management without<br />

minimizing the influence the knowledge of the tendencies may bring in the economy<br />

21

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

Tendencies shown in the culture of companies<br />

The reality has proven that a culture of companies specific for the bank system has<br />

developed in time. “The concept Uculture of companiesU includes semantically the values,<br />

symbols, beliefs, myths, rituals, ceremonies and strivings which define the spiritual space of a<br />

company.<br />

The culture of companies represents intrinsically a part of the modern approaches to the<br />

organizational and strategic management because it includes thinking and behavior patterns<br />

generated during a lifetime in a company.<br />

The culture of companies is the invisible universe of a firm made up from its primary<br />

intangible elements <strong>–</strong> knowledge and emotions structured like values, rules, beliefs, myths,<br />

symbols, etc.”[2]<br />

We will try in this study to present the trajectory of the bank system from the<br />

bureaucratic management, excessively hierarchical, to a protectionist management practiced<br />

by the state banks and finally to the effective management.<br />

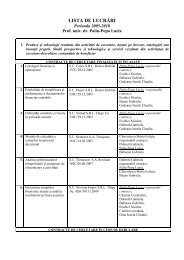

The majority of the banks from the present Romanian bank system try to achieve the<br />

last one, like the fig. nr. 1 proves.<br />

Beaurocratic<br />

Management<br />

Protectionist<br />

Management<br />

Fig. no. 1 Trajectory of the bank system management<br />

The statement “books are made from books and banks from other banks” has a little<br />

bit of truth, fact that has practically forced the banks in the beginning to apply to internal<br />

sources in the process of recruiting the personnel.<br />

The fast development of the bank system and the need to cover the whole country<br />

have encountered the weak motivation of the personnel to transfer in other towns to occupy<br />

better paid jobs in a bank, the lack of mobility and the conservatism being the main features<br />

of manpower in this domain.<br />

On the other hand, the level of remuneration of the bank’s personnel, situated in the<br />

top of the best paid jobs, has determined an infusion of personnel which theoretically should<br />

have brought a pure environment or “new openings, new ideas”.<br />

The characteristics of working in a bank made impossible for the moment a discussion<br />

about a new culture of companies in the bank system which is formed mainly by banks with<br />

state capital because it implies an excessively hierarchical environment, a rigid code of<br />

internal rules, a clearly shared work, little dynamics, and the type of personnel kept on the job<br />

even if it is unable to understand the standards of a competitive market and give up the<br />

bureaucratic work style.<br />

Even if there were only banks with state capital at the beginning of the transition<br />

period, the landscape of the bank system changed in 1991 when private banks emerged as<br />

well as banks with partial or total foreign capital. 1999 is the year when state banks gave up<br />

the initiative to banks with partial or total foreign capital through the process of selling B.R.D.<br />

and BANCPOST, followed decisively by the taking over of the B.C.R. in 2005 by ERSTE<br />

BANK Austria.<br />

The tendencies manifested throughout the entire period since 2000 made possible the<br />

present situation when five out of the first six banks operating in our country have partial or<br />

total foreign capital which means great transformations are expected from these banks<br />

concerning their management.<br />

22<br />

Effective<br />

Management

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

It is indifferent if it is about a state or private bank; the passing to the new culture of<br />

companies has to make a successfully transition from the values of the present to those of a<br />

true market economy.<br />

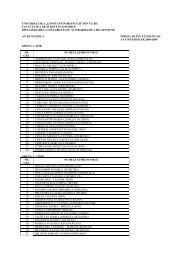

For this objective, even from this period, the new values of the culture of companies<br />

must be promoted and awarded [3], like they are shown in figure 2.<br />

Historical values of the banks Specific values of market economy<br />

Bank office=hierarchical element Bank office= profit center<br />

Characteristics Characteristics<br />

↓ ↓<br />

1. Addiction → 1. Autonomy<br />

2. Knowledge → 2. Motivation<br />

3. Quantity → 3. Quality<br />

4. Safety → 4. Risk<br />

5. Order → 5. Creativity<br />

6. Specialization → 6. Interdisciplinary sciences<br />

7. Stability → 7. Change/Transformation<br />

8. Monopoly → 8. Competition<br />

Fig. no. 2 The change of values in the culture of companies<br />

Banks seem more and more interested in introducing CRM (Customer Relationship<br />

Management) which allow them to guide their activity according to the customers’ requests.<br />

A person (that can be a possible or a real customer) may come in contact with the bank<br />

through a multitude of methods, such as:<br />

� Bank’s advertising;<br />

� Press announcements;<br />

� Information requested by phone;<br />

� Information requested in writing;<br />

� Asking at the front desk;<br />

� Accessing the bank’s site on the internet..<br />

No matter the method chosen, the customer has certain expectations when they came in<br />

contact with the bank’s personnel, as follows:<br />

� To make himself understood;<br />

� To receive details regarding matters they are interested in;<br />

� To be addressed to politely, clearly, like to a true partner;<br />

� To be treated with patience and understanding;<br />

� To feel trust and interest from the bank’s personnel;<br />

� To encounter a warm, friendly environment in the bank.<br />

In consequence, the banks have the obligation to select the personnel and train it to<br />

have the appropriate behavior; the best advertising for the bank is the favorable impression its<br />

personnel gives to the possible and real customers.<br />

Bank-customer relationship is a continuous process that has as main subject satisfying<br />

the customers’ demands in order to maximize the bank’s profit.<br />

23

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

Thinking and planning the bank’s activity must be oriented towards the comprehension<br />

of the customer’s requests, the acknowledgement of the bank-customer relationship being<br />

positive in any circumstance, respectively:<br />

� When the bank wants to be present and active on the market and have success,<br />

it must maintain its customers, because without them there is no activity. Satisfying the<br />

customers is essential foe keeping them and avoiding their migration to other banks.<br />

� When the banks want to extend, it must preserve the existing customers but<br />

attract new ones too:” the satisfied customer is the best and the cheapest marketing<br />

instrument. This kind of client will tell his friends and colleagues what type of services had<br />

been offered to him, therefore increasing the bank’s number of customers.”<br />

It is generally considered that there are four levels leading to “positive feelings of<br />

satisfaction” [6], meaning:<br />

� Precision (exactness, accuracy) <strong>–</strong> level defined by a services’ quality equal to the<br />

standard promoted in the offer;<br />

� Accessibility (guarantee, availability) <strong>–</strong> bank’s services should be offered all over<br />

in time and space without other expenses for waiting or moving;<br />

� Partnership <strong>–</strong> customers expect the bank to understand and solve their problems, in<br />

order to allow them to respect their obligations; it is a situation in which both sides win;<br />

� Counseling - customers to see the bank like a counselor who help them win<br />

together.<br />

The first two levels are absolutely necessary to prove the measure of the quality and the<br />

quantity of the given services; the next two levels prove to be essential for gaining the clients’<br />

loyalty. Some priorities of the customer relationship management in the banks’ area are:<br />

� The necessity to bring in new customers;<br />

� The growth of the deposits’ quantum and of the number of opened accounts for<br />

credit;<br />

� The growth of the number of eligible clients for the proposed loan policy;<br />

� The growth of the money circulation through the customers’ accounts;<br />

� The diversifying of takings and paying and the growth of incomes from<br />

commissions.<br />

� Higher degree of loyalty from the existing customers;<br />

� The increase in the functional capacity of the bank and the improvement of<br />

services’ quality for the customers.<br />

The bank must design a database with information on every single customer that needs<br />

to be upgraded periodically in order to acknowledge and evaluate the clients from economical<br />

and financial point of view, in the present and in the future, and to correctly appreciate the<br />

banking risk in the loan activity.<br />

The principal sources of information are:<br />

1. Information given by customers:<br />

� The application for opening the account;<br />

� The loan application;<br />

� The constituting documents of the firm or of the legal person;<br />

� Marriage certificates;<br />

� Financial reports and declarations made by the client.<br />

2. Information from the bank’s books:<br />

� the total amount of takings and payments, their periodicity, the direction of<br />

treasury main funds;<br />

� loan categories, volumes, payback deadlines, guarantees, insurances, spreading<br />

over another period;<br />

� duty service;<br />

24

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

� banking risk information;<br />

� information regarding payments incidents;<br />

� Internal audit.<br />

3. Information from external sources that may be obtained from:<br />

o Trade Register Offices;<br />

o Romanian National Bank,<br />

o National Institute of Statistics;<br />

o County Offices of the National Institute of Statistics;<br />

o National Committee for Movable Properties;<br />

o National Committee of Insurances’ Control;<br />

o Control Committee on the Fund for Private Pensions;<br />

o Chamber of Commerce, Chamber of Industry, Chamber of Agriculture;<br />

o Public Notary Offices;<br />

o other banks and institutions that have relation with customers;<br />

o insurance companies, Mayor’s offices, external audit;<br />

o Mass-media.<br />

The bank-customer relationship has for main target to bring additional value to both<br />

partners on the basis of the following principles [4]:<br />

� The mutual relationship must bring growth to both partners;<br />

� The bank must focus on assisting a reasonable number of clients, the loyal ones<br />

before the others. This attitude brings a “premium” for the bank and “Valuable<br />

customer” tag for the client.<br />

� Value means transparency and continuity in satisfying the basic banking<br />

necessities for the client;<br />

� The customer should compensate the bank by a swinging of cooperation<br />

opportunities;<br />

� The customer expects cooperation from a healthy, strong bank system that<br />

should offer a large category of banking services.<br />

Banks have already structured their activity with the customers by separating it into<br />

front-office activities and back-office activities.<br />

The personnel working in front-office is situated in the first line of the bank-customer<br />

relationship and it must respect some image standards because this merges into the bank’s<br />

image in most of the cases.<br />

Young persons are preferred, with good looks, with good IT and technology skills very<br />

communicative, carefully dressed, who know very well the products and the services offered<br />

by the bank and the norms and procedures of work.<br />

The front office persons must add to the qualities mentioned above the development of<br />

the following skills:<br />

� the art of active listening;<br />

� the art of asking the right questions<br />

� the fast acknowledgement of customers’ needs and finding the most appropriate<br />

solution to those;<br />

� the habit to easily negotiate<br />

� the possibility of thinking on long-term;<br />

� acting approachable, energetic, efficient;<br />

� the ability to gain customers’ trust easily.<br />

25

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

REFERENCES:<br />

1. Avram, V., Sisteme monetare, Editura Universitaria, Craiova, 2005, p 276<br />

2. Brãtianu, C., Management şi marketing, Editura Comunicare.ro, Bucureşti, 2006, p<br />

145<br />

3. Bucciarelli, M., Tendenze nel management bancario, Editura Sarin, Roma, 1988, p 48<br />

4. Dãnilã, N, Berea, A. O, Managementul Bancar-Fundamente şi Orientãri, Editura<br />

Economicã, Bucureşti, 2000, p. 129<br />

5. Opriţescu, M. (coord.), Managementul Riscurilor şi Performanţelor Bancare, Editura<br />

Universitaria, Craiova, 2007, p.141<br />

6. Herghelegiu, C., Managementul relaţiei cu clienţii, Revista Piaţa financiarã Nr.<br />

9/2007, p 52<br />

7. Van Greuning H., Brajovic Bratanovic, S., Analiza şi Managementul Riscului<br />

Bancar- Evaluarea guvernanţei corporatiste şi a riscului financiar, Editura Irecson,<br />

Bucureşti, 2003, p.16<br />

26

Annals of the University “Constantin Brâncuşi”of Tg-Jiu, No. 1/2008, Volume 3,<br />

ISSN: 1842-4856<br />

APPLY<strong>IN</strong>G THE NET PRESENT VALUE CRITERION<br />

0B<strong>IN</strong><br />

THE CASE <strong>OF</strong> MIXED F<strong>IN</strong>ANC<strong>IN</strong>G<br />

Prof. Nicolae SICHIGEA, Ph.D<br />

Assoc. Prof. Dorel BERCEANU, Ph.D<br />

Ec. Dan Florentin SICHIGEA<br />

Faculty of Economy and Business Administration<br />

University of Craiova<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

32BLe<br />

developpement des entreprises se realise á travers des investition et par conséquent la decision<br />

d'investicement a un importance différenté dans l'activité manageriale.<br />

L'oeuvre elaboré est centre sur la presentation d'un critere esentiale, qui repond a l'obiectif de baze de la<br />

fonction financiare, maximiser la valeur de l'entreprise c'est-à-dire, VAN (valeur actualise nette).<br />

Dans le méme temp en fonction de la modalité de financement des projets des investices on<br />

exemplifique le mode d'appliquer de differents methodes derivé de VAN.<br />

The investment option implies selecting the investment projects according to their<br />

profitability, comparing their cost to the sum of the net income gained from their exploitation.<br />

This comparison can be done without the updating, according to the principle of the<br />

arithmetic sum of the incomes and expenses estimated for the life span of the good, or by<br />

confronting the net income per year, brought in up until the moment of the option for<br />

investment, to the expense of the investment. That is why, in taking the investment decision,<br />

we use option methods without updating and methods with updating.<br />

The most frequently used updating method is the net present value (NPV), which<br />

answers to the main objective of the financial function of the enterprise, which is the<br />

maximizing of the enterprises’ value.<br />

Economical theory has instituted the law of the descending efficiency of the<br />

investment opportunities in economy, according to which the marginal efficiency of the<br />

investment is descending. Meaning, the larger the investment, the weaker the efficiency<br />

obtained for the last leu invested. That is why the one taking the decisions must know when to<br />

stop investing, without receiving a clear response from the theory, but only the basic<br />