PERSONALITY PROCESSES AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES ...

PERSONALITY PROCESSES AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES ...

PERSONALITY PROCESSES AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

STABILITY OF INTRA<strong>INDIVIDUAL</strong> BEHAVIOR PATTERNING 683<br />

Number of shared features<br />

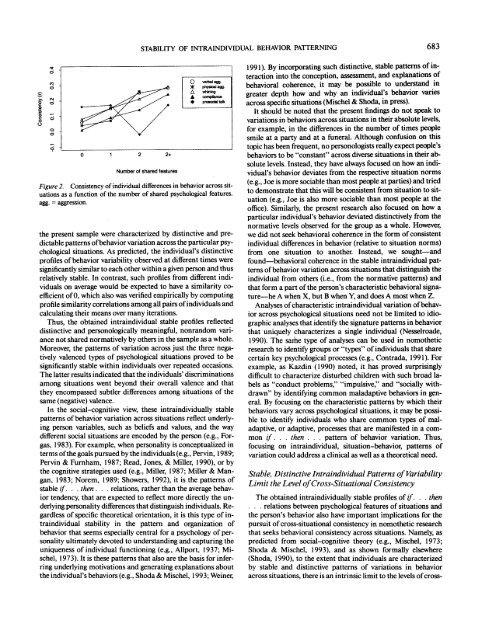

Figure 2. Consistency of individual differences in behavior across situations<br />

as a function of the number of shared psychological features,<br />

agg. = aggression.<br />

the present sample were characterized by distinctive and predictable<br />

patterns of behavior variation across the particular psychological<br />

situations. As predicted, the individual's distinctive<br />

profiles of behavior variability observed at different times were<br />

significantly similar to each other within a given person and thus<br />

relatively stable. In contrast, such profiles from different individuals<br />

on average would be expected to have a similarity coefficient<br />

of 0, which also was verified empirically by computing<br />

profile similarity correlations among all pairs of individuals and<br />

calculating their means over many iterations.<br />

Thus, the obtained intraindividual stable profiles reflected<br />

distinctive and personologically meaningful, nonrandom variance<br />

not shared normatively by others in the sample as a whole.<br />

Moreover, the patterns of variation across just the three negatively<br />

valenced types of psychological situations proved to be<br />

significantly stable within individuals over repeated occasions.<br />

The latter results indicated that the individuals' discriminations<br />

among situations went beyond their overall valence and that<br />

they encompassed subtler differences among situations of the<br />

same (negative) valence.<br />

In the social-cognitive view, these intraindividually stable<br />

patterns of behavior variation across situations reflect underlying<br />

person variables, such as beliefs and values, and the way<br />

different social situations are encoded by the person (e.g., Forgas,<br />

1983). For example, when personality is conceptualized in<br />

terms of the goals pursued by the individuals (e.g., Pervin, 1989;<br />

Pervin & Furnham, 1987; Read, Jones, & Miller, 1990), or by<br />

the cognitive strategies used (e.g., Miller, 1987; Miller & Mangan,<br />

1983; Norem, 1989; Showers, 1992), it is the patterns of<br />

stable //. . . then. . . relations, rather than the average behavior<br />

tendency, that are expected to reflect more directly the underlying<br />

personality differences that distinguish individuals. Regardless<br />

of specific theoretical orientation, it is this type of intraindividual<br />

stability in the pattern and organization of<br />

behavior that seems especially central for a psychology of personality<br />

ultimately devoted to understanding and capturing the<br />

uniqueness of individual functioning (e.g., Allport, 1937; Mischel,<br />

1973). It is these patterns that also are the basis for inferring<br />

underlying motivations and generating explanations about<br />

the individual's behaviors (e.g., Shoda & Mischel, 1993; Weiner,<br />

1991). By incorporating such distinctive, stable patterns of interaction<br />

into the conception, assessment, and explanations of<br />

behavioral coherence, it may be possible to understand in<br />

greater depth how and why an individual's behavior varies<br />

across specific situations (Mischel & Shoda, in press).<br />

It should be noted that the present findings do not speak to<br />

variations in behaviors across situations in their absolute levels,<br />

for example, in the differences in the number of times people<br />

smile at a party and at a funeral. Although confusion on this<br />

topic has been frequent, no personologists really expect people's<br />

behaviors to be "constant" across diverse situations in their absolute<br />

levels. Instead, they have always focused on how an individual's<br />

behavior deviates from the respective situation norms<br />

(e.g., Joe is more sociable than most people at parties) and tried<br />

to demonstrate that this will be consistent from situation to situation<br />

(e.g., Joe is also more sociable than most people at the<br />

office). Similarly, the present research also focused on how a<br />

particular individual's behavior deviated distinctively from the<br />

normative levels observed for the group as a whole. However,<br />

we did not seek behavioral coherence in the form of consistent<br />

individual differences in behavior (relative to situation norms)<br />

from one situation to another. Instead, we sought—and<br />

found—behavioral coherence in the stable intraindividual patterns<br />

of behavior variation across situations that distinguish the<br />

individual from others (i.e., from the normative patterns) and<br />

that form a part of the person's characteristic behavioral signature—he<br />

A when X, but B when Y, and does A most when Z.<br />

Analyses of characteristic intraindividual variation of behavior<br />

across psychological situations need not be limited to idiographic<br />

analyses that identify the signature patterns in behavior<br />

that uniquely characterizes a single individual (Nesselroade,<br />

1990). The same type of analyses can be used in nomothetic<br />

research to identify groups or "types" of individuals that share<br />

certain key psychological processes (e.g., Contrada, 1991). For<br />

example, as Kazdin (1990) noted, it has proved surprisingly<br />

difficult to characterize disturbed children with such broad labels<br />

as "conduct problems," "impulsive," and "socially withdrawn"<br />

by identifying common maladaptive behaviors in general.<br />

By focusing on the characteristic patterns by which their<br />

behaviors vary across psychological situations, it may be possible<br />

to identify individuals who share common types of maladaptive,<br />

or adaptive, processes that are manifested in a common<br />

if. . . then . . . pattern of behavior variation. Thus,<br />

focusing on intraindividual, situation-behavior, patterns of<br />

variation could address a clinical as well as a theoretical need.<br />

Stable, Distinctive Intraindividual Patterns of Variability<br />

Limit the Level ofCross-Situational Consistency<br />

The obtained intraindividually stable profiles of //. . . then<br />

. . . relations between psychological features of situations and<br />

the person's behavior also have important implications for the<br />

pursuit of cross-situational consistency in nomothetic research<br />

that seeks behavioral consistency across situations. Namely, as<br />

predicted from social-cognitive theory (e.g., Mischel, 1973;<br />

Shoda & Mischel, 1993), and as shown formally elsewhere<br />

(Shoda, 1990), to the extent that individuals are characterized<br />

by stable and distinctive patterns of variations in behavior<br />

across situations, there is an intrinsic limit to the levels of cross-