Literary Journal Issue#5 2011 - Cranbrook School

Literary Journal Issue#5 2011 - Cranbrook School

Literary Journal Issue#5 2011 - Cranbrook School

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Literary</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Issue#5</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

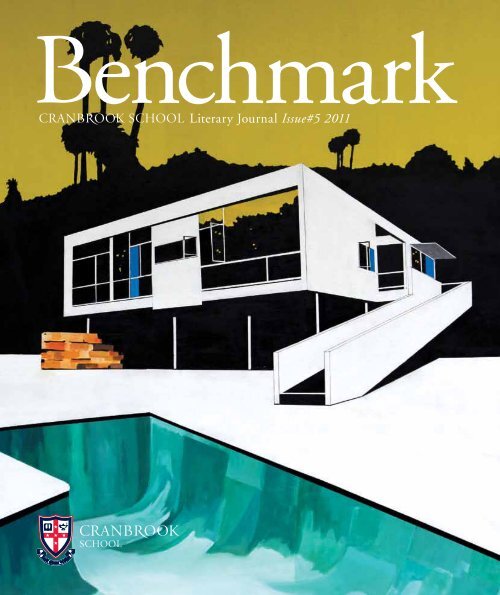

CRANBROOK SCHOOL <strong>Literary</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Issue#5</strong> <strong>2011</strong><br />

Published by CRANBROOK SCHOOL<br />

Editor: Jacqueline Grassmayr<br />

Fifth Edition: <strong>2011</strong><br />

Designed and produced by <strong>Cranbrook</strong> Publications<br />

Front cover: ‘Prime’ – Painting by William Solomon Year 12

Contents<br />

Editorial ..................................................................... 1<br />

Poetry ........................................................................ 3<br />

Creative Writing ...................................................... 19<br />

<strong>Literary</strong> and Cultural Criticism ................................ 61<br />

Fine Arts .................................................................. 74<br />

Languages ............................................................... 82<br />

History ..................................................................... 95

BENCHMARK<br />

Editorial<br />

Welcome to the fifth edition of Benchmark which I hope will delight<br />

and engage you over the summer months.<br />

We were privileged this year to have poet Toby Fitch work with students<br />

as part of The Red Room Company’s education program, ‘Papercuts’. Toby<br />

Fitch is a talented new poet recently featured in the Sydney Morning Herald’s<br />

‘Spectrum’. His first full length book of poems is about to be published<br />

by Puncher and Wattman. The Red Room Company is a non-profit<br />

organisation that creates, promotes and publishes new Australian poetry in<br />

imaginative, inspiring and magical ways. For more information, view their<br />

website at redroomcompany.org. Some of the poems the students created<br />

for their anthology, attempted defiance, are published here. The boys have<br />

swaggered along the more rebellious laneways of their minds and left a trail<br />

of poetic musings in their wakes. I am sure that you will agree they are<br />

edgy and thought-provoking pieces.<br />

As always, I thank Tony Ronaldson for his wise editing advice. He and<br />

I spend many hours reading the poems selected by teachers, and are always<br />

delighted to see such a wide range of topics and poetic forms. Every year we<br />

are also highly impressed by the craft and skill of the competition winners.<br />

Thanks must also go to the English teachers who challenge, guide and<br />

inspire their students to write the pieces that appear in the Poetry, Creative<br />

Writing, and <strong>Literary</strong> and Cultural Criticism sections of the journal.<br />

This year, I have published two excerpts from the ‘Write-a-Book-In-a-Day’<br />

competition. As we go into publication, we await the announcement of<br />

1

EDITORIAL<br />

this year’s winners and wonder if we will match the successful entry from<br />

the 2010 Year 8 English Enrichment team. The boys must write, illustrate<br />

and publish a book within a twelve-hour time limit. The competition is<br />

a literary and fundraising initiative of the Katharine Susannah Prichard<br />

Writers Centre and Princess Margaret Hospital Foundation. This year<br />

the proceeds from NSW go to The Oncology Children’s Foundation<br />

(Westmead). For more information, you can view their website at<br />

writeabookinaday.com.<br />

Thanks also go to Anne Byrnes, Matthew Ross and Cathleen Jin for<br />

their selections in the History and Languages sections respectively.<br />

Thank you to the Art Department whose students are clearly motivated<br />

by the passion their teachers radiate. Their work is adventurous in content<br />

and professional in execution. Thank you to Rhondda Anthony, Chloe<br />

Hodgson and the members of the Publications Department for their tireless<br />

efforts in designing and producing such a beautiful journal. And, of course,<br />

thank you most of all to the boys for their contributions.<br />

This edition of Benchmark is dedicated to the memory of our dear<br />

colleague, David Ingham (1944 – <strong>2011</strong>) who gave the literary journal<br />

its title. Dave filled our lives with literary quips, poetic gems, laughter,<br />

generosity and warmth. He is greatly missed.<br />

Jacqueline Grassmayr<br />

Editor<br />

2

BENCHMARK<br />

3

POETRY<br />

Well Groomed<br />

Ba-ding! ‘Chris Jones,’ who the …<br />

‘Hey just moved here lol probs coming to your school next term.’<br />

Four hours and facebook chat really starts to grasp your social life.<br />

Pop up. Hannah just logged on. Must. Start. Convo. Reaching for the<br />

pack, eww Ready salted. Must. Get. Water.<br />

Ba-ding. Not the new kid again.<br />

‘You still there? … QUESTION MARK, QUESTION MARK.’<br />

Can’t take it any longer …<br />

‘Hi.’<br />

Initial greeting must be subtle with slight hostility,<br />

No Xs or Os for this one just yet. Ba-ding<br />

‘How old are you? Im 16. Just moved from the country.’<br />

OH GOD a country boy. Have to tell Jess about this one.<br />

I bet this is his first time on a computer let alone the Internet.<br />

‘Yeah same im 16. So how do you know what school I go to?’<br />

Good answer. Showing interest but still slightly respectful.<br />

Wait how did he know what school I went to …<br />

info page that’s it, of course. Had me worried for a bit then.<br />

Four days in, country boy won’t. Leave. Me. Alone.<br />

Kind of growing on me. Maybe its his innocence,<br />

his vague understanding of social networking …<br />

or just his plain willingness to persist.<br />

Either way convos keep getting deeper and deeper.<br />

Jess says he’s weird. Says I shouldn’t talk to him.<br />

SCREW HER. She’s just jealous. That’s right.<br />

Back stabber can go die for all I care.<br />

<strong>School</strong> started, boring as usual.<br />

Teacher mumbles, listen, straight out the other side.<br />

Time seems to slow down like walking through a retirement home.<br />

Talked to Jess. Didn’t go so well. In short …<br />

me angry. Clench fist. Bloody nose.<br />

But we made some ground.<br />

Preliminary social contact has to mean something right.<br />

No country boy today,<br />

Weird said he’d be here.<br />

Ba-ding. ‘Sorry I wasn’t there today, I was spewin. Feel better though.<br />

Wondering if you want to meet up?’<br />

Contemplation. To meet or not to meet, that is the question.<br />

Why not? Closest thing I have to a friend at the moment.<br />

A lonely wolf amidst a pack. Sad but true.<br />

‘Where and when?’ Ba-ding. ‘Steyne Park, four?’<br />

An out guy hmm whatever floats your boat.<br />

Tonight on Nine News.<br />

Reports just in that a sixteen-year-old girl was found dead<br />

in Sydney’s east.<br />

Oliver Spence<br />

Year 10<br />

Winner of the Year 10 Poetry Prize<br />

4

BENCHMARK<br />

Mighty Beowulf<br />

King of the Geats<br />

Damaged and dying, Grendel disappeared into the darkness.<br />

Unaware of the threat that remained, the Danes celebrated.<br />

Yet as night fell, they felt the fury of Grendel’s mother.<br />

She came in a rage to wreak revenge<br />

and before dawn, they found Aschere, dead on the floor.<br />

‘Time lost lamenting is time wasted. Let us avenge our friend!’<br />

screamed the furious tribe.<br />

Brave Beowulf led the way to the lake<br />

where deep below, Grendel’s mother lay in wait.<br />

‘Death or destruction, I will face my fate!’<br />

cried Beowulf as he leapt to the lake.<br />

He plummeted into the gloomy green depths.<br />

The icy cold water grabbed his breath away.<br />

Suddenly something tight grabbed his chest …<br />

Beowulf was dragged into an underwater cave.<br />

Gasping and gagging, he found himself face to face with<br />

a hideous hag, Grendel’s mother.<br />

The clash of steel and the striking of claws raced<br />

through the echoing chamber.<br />

With a silver flash of the sword, Grendel’s mother<br />

was slaughtered.<br />

Her bloodied head lay crimson on the dark floor.<br />

Beowulf turned to see Grendel in shock and<br />

With one sweep of the sword Grendel’s head rolled<br />

beside her mother’s.<br />

As Grendel’s blood bubbled to the surface of the lake,<br />

Beowulf’s companions gasped in horror.<br />

Suddenly out burst Beowulf with two heads held high.<br />

The companions raised the head up on spears and cheered<br />

Mighty Beowulf, King of the Geats!<br />

Roly Storch<br />

Year 7<br />

5<br />

In Grandpa’s<br />

House<br />

My eyes shoot open in the gloomy dark,<br />

Slowly adjusting to the light.<br />

I quietly slip out of the warmth of my bed,<br />

Suppressing the urge to shiver.<br />

My bare feet touch the ancient floorboards<br />

that creak and groan; ready to bend and break.<br />

As I stumble blindly to my bedside desk,<br />

grasp a beacon of hope and<br />

switch it on and smile,<br />

my trusty flashlight is dependable.<br />

I creep towards the towering obstacle,<br />

Trying to hide my fear.<br />

Turning the knob for all eternity …<br />

until finally the door swings open.<br />

this is the night, this is the night,<br />

in Grandpa’s house,<br />

I have waited for, all my life.<br />

Poking my head out into empty space,<br />

I check the coast is clear.<br />

My body doesn’t make a sound<br />

as I step out into the corridor.<br />

I raise my flashlight to my next destination;<br />

thin beams of light cut through darkness.<br />

As I tip-toe down polished floors<br />

my heart’s thumping loudly; adrenaline pumping.<br />

Stopping in front of my second obstacle<br />

I pause to catch my breath<br />

and breathe deeply, in and out.<br />

I press my ear against Grandpa’s door, feeling the icy cold.<br />

My heart skips a beat as I hear the rumbling of the old man’s snores<br />

which guarantees my success.<br />

This is the night, this is the night,<br />

in Grandpa’s house,<br />

I have waited for, all my life.<br />

I can barely contain my excitement right now,<br />

but I need to stay focused.<br />

The hardest part dawns and looms silently<br />

in the darkness ahead.<br />

I set out into the obscurity,<br />

guided only by my flashlight.<br />

I search and search and search in the dusty corridor<br />

but I can’t seem to find it.<br />

I can almost hear the laughing now

POETRY<br />

fading in the darkness.<br />

Suddenly, something touches me!<br />

I nearly faint on the spot.<br />

But yes, oh yes. I’ve found it!<br />

The dangling cord to the attic above.<br />

This is the night, this is the night,<br />

in Grandpa’s house,<br />

I have waited for, all my life.<br />

Tugging hard with all my strength,<br />

I conquer my last challenge.<br />

The stairs come down majestically,<br />

hitting the floor with only the softest of thumps.<br />

As I grasp the hand rails, my knuckles turn white.<br />

Torch in mouth and destiny in hand,<br />

I slowly ascend into the blackness above,<br />

still not believing this is happening.<br />

I pull myself up onto the attic’s floor,<br />

dust covering my body.<br />

On all fours, I turn around,<br />

and looking, I gasp,<br />

‘I see it, I see it! It’s really here …’<br />

The forbidden door of Grandpa’s attic.<br />

This is the night, this is the night,<br />

in Grandpa’s house,<br />

I have waited for, all my life.<br />

I stand up, full height and chest broad,<br />

to Grandpa’s forbidden door.<br />

It’s a good foot bigger than me.<br />

I tingle with excitement.<br />

I see the burnished brass knob<br />

reflecting in the torchlight<br />

and I can’t help but laugh.<br />

‘I’ve fooled Grandpa, I’ve fooled Grandpa,<br />

at last I’m finally here.’<br />

I step forward and swing the door ajar …<br />

The air is still, quiet as usual, as I shine my torch to the door.<br />

But the door remains black; no light gets through!<br />

As a great roar fills my ears and my feet are pulled off the ground,<br />

I’m sucked into oblivion, falling and falling and falling.<br />

This is the night, this is the night,<br />

in Grandpa’s house,<br />

I have waited for, all my life.<br />

I’m hurled back out of the attic’s door.<br />

My body is thrown across the room.<br />

I sit up, head spinning,<br />

dizzy beyond thought<br />

and I lurch to my feet, holding the wall,<br />

not thinking clearly.<br />

I’m still in Grandpa’s attic,<br />

just the way I left it.<br />

I’ve lost my torch, but I can see.<br />

Light comes from the window.<br />

I cast the blinds open<br />

and squint in the light …<br />

And the horror seeps in that I’m caged.<br />

This is the night, this is the night,<br />

in Grandpa’s house …<br />

I had waited for,<br />

All my life …<br />

Michael Turner<br />

Year 7<br />

Winner of the Year 7 Poetry Prize<br />

6

BENCHMARK<br />

Living History<br />

I’ve got an aunt in Narrabri,<br />

She’s 80, and half as tall as me.<br />

I like her so; she’s very nice.<br />

She asks me ‘round for scones and tea.<br />

She tells me stories of her life,<br />

Of places she has been,<br />

Of famous people she has met<br />

And things that she has seen.<br />

I think her memory’s faulty,<br />

As she’s getting on in years,<br />

And sometimes when she talks to me,<br />

Her eyes well up with tears.<br />

‘Lost my son in Vietnam,’<br />

She’ll say and shake her head.<br />

‘I won’t forget that pointless war,’<br />

Is all she ever said.<br />

‘My husband used to work the land,<br />

For farmers near and far,<br />

But his greatest love was at the pub,<br />

Propping up the bar.’<br />

‘His tombstone’s in the churchyard,<br />

Which I rarely ever see.<br />

I couldn’t care if it was gone,<br />

Makes no difference to me.’<br />

What a line – that said it all,<br />

The life that she has led,<br />

The tough times she’s endured,<br />

Shown in things she said.<br />

Sometimes we wander round the back,<br />

To a car parked in the drive.<br />

She strokes the hood and says to me<br />

‘It’s from 1965.’<br />

‘A Thunderbird from Ford,’ she’d say<br />

‘A gift when I turned 18,<br />

I used to drive it everywhere,<br />

It’s a wonderful machine.’<br />

‘I’d like to drive again, someday.’<br />

But I know she never will.<br />

The battery’s dead, the tyres are flat<br />

And weeds grow in the grill.<br />

7<br />

And each day when it’s time to go,<br />

She says, ‘What a lovely talk.’<br />

I nod my head, I say ‘goodbye’<br />

And out the door I walk.<br />

‘Come again tomorrow,<br />

I’ll tell you something new.’<br />

I nod my head and close the gate<br />

And call out, ‘Tootle-loo!’<br />

Sadly, as I leave the house,<br />

I think, ‘Does she even know my name?’<br />

Because I know the next time I come back<br />

She’ll repeat it all again.<br />

Scott Ewart<br />

Year 9<br />

Winner of the Year 9 Poetry Prize

POETRY<br />

Study Fishing<br />

You don’t want to, but you have to<br />

Your heart sinks to your stomach<br />

You look out the window<br />

The birds sing, the sun shines<br />

Every fibre screams to be outside<br />

You glance at the papers … Maths … Oh God …<br />

Like hacking your way through weeds<br />

An eternal punishment<br />

You become restless and tired<br />

TV wanders through your mind<br />

NO YOU HAVE TO CONCENTRATE!<br />

You switch on the TV, some daily cooking show<br />

You stare at the clock, beg it to stop<br />

Time lingers<br />

Guilt, stress, anger starts to flow<br />

And eat at your soul<br />

You grunt and wriggle, your face goes dry<br />

Your mind races, you tap your feet.<br />

Your blood boils. You gnaw your pen<br />

You’re on the verge of tears<br />

Until you just yell STOP!<br />

You stare at the ceiling<br />

Swivel in your chair<br />

Your fingertips skim the ground<br />

What should you do?<br />

What should you think?<br />

You’re stuck in quicksand<br />

Sucked into a black hole<br />

Powerless<br />

You rise and step outside<br />

The sunshine skips across your face<br />

The fresh air fills your lungs<br />

Cling on, life is larger<br />

Than some dumb test<br />

Oscar Whatmore<br />

Year 10<br />

The rain beats down upon the wooden roof.<br />

We prize open our eyes, crawl from warm beds.<br />

The dawn remains aloof.<br />

Numbed fingers sift through tangled lines.<br />

Lift sinkers and floats, pack lines and rods.<br />

Leave the dog to whine.<br />

Scuffling and shuffling down the loose slate hill,<br />

Carrying tackle, bent double against the wind.<br />

Hopeful despite the chill.<br />

The rain drizzles out and the boat comes into view.<br />

Rotting bait stinks. Exhaust fumes pervade.<br />

The dawn receives its cue.<br />

The cabin folds into the coastline, the boat judders forward.<br />

The clump of rocks in sight, we wash to a halt,<br />

Lowering our lines for reward.<br />

Steaming thermosed coffee drunk with trembling fingers.<br />

Sinkers strike murky water. The boat bobs.<br />

Fish aren’t caught by malingerers.<br />

The sun arcs overhead and still no fish are caught.<br />

Our cradle rocks. Our cradle rocks.<br />

Tempers are short.<br />

The cry goes up. Fish on! Fish on!<br />

The king has bitten. The king has fallen.<br />

Tension released. He’s gone.<br />

Angus Forth<br />

Year 11<br />

Winner of the Year 11 Poetry Prize<br />

8

BENCHMARK<br />

The Wharf Sand<br />

Bursting out the door,<br />

Sucking in delicious warm air and<br />

the smell of the cherry blossom tree.<br />

Laughing, we run down the granite stairs<br />

and look up at the bright beautiful blue sky.<br />

The slap of our thongs rhythmical as<br />

we pass the school, cross the road, run down the street.<br />

Finally we push open the black gate.<br />

I kick off my thongs and stand on the edge.<br />

I face my friends, they pressure me on,<br />

fear pumps adrenaline through my veins,<br />

the sparkling blue calls for me,<br />

my body is frozen.<br />

I can.<br />

Suddenly the ice melts,<br />

I jump, flipping backwards.<br />

I hover hollow in the air and stare at my friends.<br />

I am weightless,<br />

I float through the warm air<br />

and feel its gentle touch rushing up through my body.<br />

Splash!<br />

The water licks my legs,<br />

sucks in my body.<br />

Salt, the taste of summer<br />

I open my eyes. The colour of joy.<br />

The sun shines on the water like golden crystals.<br />

I float in the glistening light blue<br />

and let it wash away all my thoughts.<br />

Eamon Hugh<br />

Year 8<br />

Winner of the Year 8 Poetry Prize<br />

9<br />

Water lapped at the sand,<br />

swirling and churning,<br />

filling in foot prints,<br />

making the sand once again smooth and moist.<br />

The fat man sat on his deck chair humming to himself.<br />

The small tuft of hair left on his pink head danced and<br />

swayed in the warm wind.<br />

His nostrils flared and<br />

his toes dug deep into the sand.<br />

The wind brought the scent of ice-cream and hot dogs.<br />

Over by the rocks children chirped like sea gulls,<br />

running and hopping around a flamboyant van.<br />

Six small children sat grinning,<br />

slurping creamy white ice-creams as their parents fussed,<br />

rubbing sun block into their peeling backs.<br />

The fat man rolled over and chuckled as water licked his<br />

feet over and over again,<br />

washing off the sand.<br />

How he wished he was a grain of sand,<br />

twisting and turning at high tide,<br />

crispy and golden at low,<br />

stuck between the toes of children,<br />

constantly travelling and exploring,<br />

sitting back enjoying the ride.<br />

Harry MacGibbon<br />

Year 9

POETRY<br />

Traces<br />

Vestiges<br />

Left in sand<br />

Washed up by the sweeping tide<br />

Lie in little puddles, squelching by<br />

Wind echoes on the arid coast<br />

Silence is imprisoned by the broken sea<br />

Chained<br />

Battered<br />

Discarded in an assaulting swoop<br />

Shells, fluttering on the surface<br />

Driftwood bobs on the sea<br />

Little stories<br />

Of times gone by<br />

Shipwrecks, floods, waste<br />

Vestiges<br />

Left behind.<br />

Jack Holloway<br />

Year 11<br />

Eagles<br />

They soar through the light blue,<br />

Zooming around on strings<br />

Held by unseen puppet masters.<br />

As they swim through the inverted seas,<br />

A black streak thunders toward the glossy foliage<br />

And curves back up to its glossy flock.<br />

Caught in its rusted iron hands,<br />

An expensive meal,<br />

Found only in the most exclusive of diners.<br />

At its address,<br />

A young calls to the heavens.<br />

The echo shoots through the atmosphere<br />

Striking its mother in mid-flight.<br />

Down below the airborne crowd,<br />

The avians’ actions are mirrored by scaly fish,<br />

Who are born, raised and buried,<br />

In the dark blue veins of the Earth.<br />

Tom Roche<br />

Year 8<br />

10

BENCHMARK<br />

Boat on the<br />

Horizon<br />

There was a boat on the horizon<br />

Endeavour<br />

An outsider<br />

A people<br />

They glow a pearly white<br />

They’re constricted by blue and red<br />

They speak in loud licks<br />

Shrill as the cockatoo<br />

Smallpox and muskets<br />

Death and destruction<br />

Thousands of years<br />

Altered in minutes<br />

They pave the land drab<br />

They fence the land jigsaw<br />

They cross the land black<br />

Terra nullius<br />

We are the nation of plenty<br />

The land of sweeping plains<br />

A people of open arms<br />

A people of deep-found fear<br />

There is a war<br />

There is persecution<br />

We are the haves<br />

They are the have-nots<br />

Inferno in Arafura<br />

Overboard at Christmas<br />

The island nation<br />

Turns a blind eye<br />

22 million<br />

6 thousand<br />

It is our decision<br />

There is a boat on the horizon<br />

James Ross<br />

Year 10<br />

Winner of the C A Bell Memorial Prize for Poetry<br />

11<br />

Perfection<br />

Ski boots tap<br />

Gloves fit snug<br />

Goggles press tight<br />

Helmet straps on<br />

Eyes scan ahead<br />

Blood gushes through<br />

Breathe in … out … in … out …<br />

Ready<br />

1, 2, 3<br />

Dropping!<br />

Blood starts to rush<br />

Skis go wider<br />

Jump looms closer<br />

Off the edge<br />

Floating in time<br />

Weightless, fearless, invincible<br />

Descending with winged feet from the realm of the gods<br />

Perfection.<br />

Spencer O’Connor<br />

Year 7

POETRY<br />

The Meet<br />

Anticipation,<br />

fear and excitement build<br />

as you arrive at a park unknown on the outskirts.<br />

Jogging the course you assess your rivals<br />

and the terrain you will be covering.<br />

Time to stretch.<br />

Starting line-up is called.<br />

You walk calmly over<br />

trying to not show your fear.<br />

Silence.<br />

Then BANG!<br />

Nerves bounce as you sprint to the first turning.<br />

You push people out of the way,<br />

fight for balance.<br />

You take the lead.<br />

The last bend.<br />

Cheers sound drugged in the back of your head.<br />

All you hear is your breathing and your competitor’s<br />

breaths.<br />

You give a push;<br />

he pushes back even harder.<br />

50 metres to go.<br />

Give it all you can.<br />

Sprint.<br />

Your competitor falls further behind.<br />

Last 5 meters.<br />

Give it all you can.<br />

Lunge forward.<br />

Your body pushes through the red ribbon then<br />

slumps<br />

with breathing problems.<br />

You shake your competitor’s hand.<br />

‘Where … did … I … ?’<br />

You gasp for air<br />

and then you see the<br />

Shield … the CAS Cross Country Shield<br />

And you know … you know you have won.<br />

George Taylor<br />

Year 9<br />

A Noisy Escape<br />

Bang! Bang!<br />

The tent is erected.<br />

Chop! Chop!<br />

The axe is at work.<br />

Swoosh! Swoosh!<br />

The wind in the trees.<br />

Ripple! Ripple!<br />

The river is running.<br />

Chirp! Chirp!<br />

The birds are here.<br />

Bounce! Bounce!<br />

The kangas are out.<br />

Crackle! Crackle!<br />

The campfire’s burning.<br />

Scream! Scream!<br />

Marshmallows on fire.<br />

Crunch! Crunch!<br />

Someone’s gone for a pee.<br />

Rustle! Rustle!<br />

Who’s rolled over?<br />

Buzz! Buzz!<br />

The dreaded mosquitoes.<br />

Zzzzzzzzzz!<br />

Dad’s started snoring.<br />

At last in the dead of night.<br />

The sound of silence.<br />

Alex Sheen<br />

Year 9<br />

12

BENCHMARK<br />

Sachsenhausen Hymn to Apollo<br />

I see the bodies: carcasses<br />

heaped, dead, mountainous.<br />

arms and legs like sticks, rib cages protruding from chests<br />

straining to break the skin,<br />

desperate to escape the misery and terror of their owner.<br />

I too am a skeleton, a ghost of the man I once was.<br />

I’m trapped,<br />

encircled by the grey walls, grim guns and ghastly<br />

grinning guards.<br />

Only God can help me but<br />

what God?<br />

A God who has forsaken us,<br />

who lets his people perish.<br />

Satan has won<br />

Like zombies, we work, we sleep, we work, we sleep.<br />

We are rubbish, dumped<br />

to rot en masse.<br />

We are vermin,<br />

filthy and unwanted<br />

slaves.<br />

They make us stand in the freezing cold and<br />

watch us die.<br />

Hell’s destruction could not outdo the death camp’s<br />

horrors - nothing could.<br />

We approach the building,<br />

the one with the chimney<br />

from which no one returns.<br />

Mothers screaming, children crying.<br />

I surrender.<br />

Samuel Atkinson<br />

Year 8<br />

13<br />

You chase away the clouds with piercing gaze,<br />

And we below live by your constant light.<br />

You bring what warmth there is on dying days,<br />

Yet not the earth alone does you give sight.<br />

You gave us music with your golden lyre,<br />

And oracles predict the changing flow<br />

Of fate to kings and men; yet in your ire<br />

Send plagues, strike heroes down with quick strung bow.<br />

Without your presence we would dwell in dark,<br />

And live with baser instincts holding reign.<br />

Phoebus, hear this paean, shoot your spark,<br />

Your sacred arts someday we may attain.<br />

Chased by time, a brief and fleeting shade,<br />

Are we, who by your godly chords are swayed.<br />

George Polonski<br />

Year 11

POETRY<br />

The Painter<br />

At midnight, in my dreams behind my eyes<br />

in the last fragments of sunlight-staining<br />

like a broken cathedral window,<br />

the colours dance for me.<br />

When I was young,<br />

the deep blue, the corn-field yellow, the fiery red<br />

of a setting sun<br />

tore me from my business<br />

and bade me worship<br />

with my brush.<br />

To the right, scarlet singing<br />

from the canvas with a shriek of delight<br />

meets, from the left, yellow!<br />

Up and down:<br />

Tears from the rose, warmth<br />

from the moon, serenity.<br />

Turquoise, like a fog upon a winter’s afternoon,<br />

swirls, careens, tumbles like an acrobat.<br />

Every starry night:<br />

eternity in my eyes, on my tongue<br />

my very blood, my all.<br />

But the colours are cruel.<br />

They scream at me:<br />

in every daub, a shading out of place, a mutiny.<br />

You weak, sentimental little man!<br />

We’re crying when you should’ve made us bleed.<br />

You’ve ripped us when we should be still.<br />

Your heart, your soul, your will: dependent on your needs.<br />

We’ll make you beg and kneel for release.<br />

It is too strong a rebuke<br />

to plant the seeds of my destruction in meagre happiness.<br />

Too hard.<br />

I cannot but chastise myself with paint-flicked fingers<br />

and join the laughter of the villagers.<br />

There goes the mad, red-haired painter with a blinded muse,<br />

the lyrist of some one-stringed instrument that wails<br />

night and day with no relief,<br />

critiquing himself with his one torn ear.<br />

I can feel the moment when the colours speak<br />

and ecstasy fills me once again.<br />

It fills me with the raucous laughter of crows,<br />

behind their beaks a promise of grace<br />

I cannot touch or see.<br />

My soul the palette, my madness paint.<br />

Joss Deane<br />

Year 11<br />

14

BENCHMARK<br />

Pfft, Poetry:<br />

Who Needs It?<br />

I’ve never quite gotten the hang of poetry.<br />

It has never really clicked.<br />

Below are just a couple of phrases<br />

Of bad examples I have picked.<br />

Awful attempts at alliteration<br />

Are all I can achieve.<br />

And despite desperate degrees of effort<br />

My assonance is still naive.<br />

My similes don’t come to a point,<br />

They’re as nonsensical as Swedish rye bread.<br />

And as for my personification,<br />

Why, the words have simply fled.<br />

Oh the difficulty with rhyming words<br />

They never seem just right.<br />

As can be seen by my last sentence,<br />

Which doesn’t even rhyme.<br />

Edward Clarke<br />

Year 10<br />

15

POETRY<br />

The following poems were created by Year 10 Enrichment students as part of the Red Room Company’s<br />

education program, ‘Paper Cuts’. They appear in the anthology attempted defiance edited by Toby Fitch.<br />

Fly the Coop Like the Hyena<br />

Slightest breeze ruffles his hair<br />

Sandstone cracks and crumbles below foot<br />

The sun crisps his skin<br />

His wings unfold<br />

Green, grey, blue<br />

The colours of Sydney envelop him<br />

Shuffling over edge<br />

He flies the coop<br />

A moment of pure stillness<br />

He is not land<br />

Not water<br />

But it rushes through him<br />

The world accelerating<br />

Gale plasters his face<br />

Chaos reigns free<br />

Brace for impact<br />

James Ross<br />

Year 10<br />

Winner of the C A Bell Memorial Prize for Poetry<br />

He traverses suburbia<br />

Claws wrapping spray-can<br />

He slinks the fence<br />

Glances the corner<br />

Taxi coasts by like a shark<br />

He dives to ground<br />

Punches ink to Coke ad<br />

Paint oozes, blood from a gazelle<br />

Launches and scoots<br />

Success running through his veins<br />

Wild smile torn across his face<br />

Like a hyena<br />

James Ross<br />

Year 10<br />

Winner of the C A Bell Memorial Prize for Poetry<br />

16

BENCHMARK<br />

Secret Scenes<br />

There’s a picture of Justin Bieber<br />

In my drawer, on my desk, above my bed.<br />

I have all his tracks,<br />

But I pretend I hate him when<br />

My friends talk about him.<br />

***<br />

Mr Fitch asks for my homework,<br />

I tell him I handed it in<br />

Even though I forgot I even had<br />

That assignment.<br />

I convince him that he lost it.<br />

***<br />

Mum glares at me, who<br />

Took the Jack Daniels?<br />

Sweat rolls off my forehead,<br />

My legs turn to clouds<br />

I also took the cookies.<br />

***<br />

Chasing Sarah down the alleyway,<br />

Smiles break across my face,<br />

Another girl playing<br />

Hard to get.<br />

I double my efforts.<br />

***<br />

Virtual eyes follow me,<br />

The door invites me in, and I oblige,<br />

Demolishing the toilets:<br />

Bang! Bang! Bang! Walk out<br />

As if nothing happened.<br />

Jonathon Li<br />

Year 10<br />

17<br />

? Do<br />

others wonder what I think?<br />

Does an ember think about the ash?<br />

Do the waters stare at the sky, feel empty<br />

if the stars don’t show?<br />

Where will the pebble reach the bottom of the lake?<br />

Are green clouds jealous of rainfall?<br />

Do shadows always follow?<br />

What is it like to be the shiny shell in the sand?<br />

Does time have colour?<br />

Is there a reason to ask in the first place?<br />

Jack Rathie<br />

Year 10

POETRY<br />

A Rebel<br />

From the moment I wake to the second I sleep<br />

I’m suffocated by rules and caged behind the law<br />

Engulfed by the commands of others<br />

But not today no I’m taking a strike and taking a stand<br />

Saying no to being quiet in the library<br />

I’ll talk when I want and as loud as I want and you can’t<br />

reproach me<br />

Refuse to write out the question before the answer<br />

And reject washing and scrubbing what menial chores!<br />

What do I care if mould colonises the sink<br />

If we run out of plates and revert to our hands<br />

Who says I don’t know what’s best<br />

Who says that food is expired because of a date on a can<br />

These imprudent rules grip you suckers<br />

Model citizens of good hygiene upholding your cherished law<br />

You can lecture me day and night like a wretched machine<br />

But deep down I know you’re as dirty as me<br />

Finn Hugh<br />

Year 10<br />

The Frozen<br />

Moment<br />

It’s when we’ve gone under<br />

When we’re all tucked in and cosy<br />

When we lie in bed content and dreamless<br />

When the static of the day has faded<br />

Shielded from the frozen moment<br />

It’s then that he walks the streets<br />

That he confides in the moon and stars<br />

Fighting his unending war<br />

Through valleys of darkness<br />

And he wonders where the plunge began<br />

Mackenzie Baran<br />

Year 10<br />

18

BENCHMARK<br />

19

CREATIVE WRITING<br />

Write-a-Book-in-a-Day<br />

An excerpt from<br />

Terror Amongst the Trees<br />

Chapter One<br />

A cacophony of drills and machinery saturated the air<br />

around Joe. However, he was oblivious to the sounds<br />

around him, his mind singularly focused on the timber in<br />

front of him. With experienced care, he pressed the drill<br />

in again, creating whirlwinds of frayed wood with the<br />

powerful machine.<br />

Absorbed in this task, he barely noticed when his mobile<br />

phone began to ring. The vibrations, however, snapped<br />

him out of his trance. As he reached for it, his hand<br />

slipped and the drill tumbled out of his hand. As it fell,<br />

it carved out a deep channel into the timber.<br />

‘Bollocks!’ Joe shouted. He lunged for the drill as the<br />

phone bounced out of his hands and catapulted into the<br />

air. He snatched the drill out of its plunge before it could<br />

do any harm. His phone, however, did not receive the<br />

same treatment. It hit the ground and shattered into<br />

hundreds of pieces. The ringing died out. ‘Bugger!’<br />

He cursed and swept up the broken pieces with his boot.<br />

Behind him, he could feel eyes turning towards him. He<br />

tried to cover up the mess even though it was now too late.<br />

‘Mr Landers,’ a voice said behind him. He turned<br />

disgracefully around to meet his boss’ eyes. ‘My office.<br />

Now.’ Like a lamb to the slaughter, Joe did as he was told.<br />

The office was cool compared to the sweltering heat<br />

outside, the boss sat down and motioned for Joe to<br />

do likewise.<br />

‘It has come to my attention that you have been, shall we<br />

say, a little clumsy. This is not the first time but has been<br />

repeated several times over the last week. I do not want to<br />

have to make this decision, but I’m afraid that I have no<br />

choice. I would like you to look for another job,’ the boss<br />

stated. Joe was taken aback. He couldn’t believe what he<br />

was hearing.<br />

‘But I’m your best worker. I’ve been working for you for<br />

over two years now. You can’t just fire me!’<br />

‘I’m afraid we can, and we must. You have been very<br />

careless lately and have often jeopardised the project.<br />

We feel that it is time for you to move on. Our decision<br />

is final.’<br />

Broken, Joe left the office. A cloud of despair billowed<br />

behind him and followed him all the way to his<br />

apartment. It was a mess; clothes were strewn all over<br />

the floor and his bed. The only surface, a small table in<br />

the centre of the room, was littered with half-eaten food.<br />

The television was on full blast, even though Joe wasn’t<br />

watching it. The sink was leaking and dirty dishes were<br />

piled up in the sink. Solemnly, he stepped over the<br />

disgusting mess and took a can of beer from the fridge.<br />

Taking a sip, he pushed a week-old singlet off the chair<br />

and sat down in front of his computer. Joe sighed,<br />

wondering where to start. Jobs were scarce these days and<br />

he knew what trials were ahead of him to secure another<br />

occupation. Soberly, he opened up the web browser and<br />

began searching.<br />

***<br />

Three days later, after several hours searching the Internet,<br />

he heard his home phone ring.<br />

‘Joe Landers here.’<br />

‘Gerald Fitzroy. I have been looking for a builder of<br />

your qualifications for some time. There is a particular<br />

assignment I believe would be right up your alley. My<br />

aunt Elizabeth currently lives in a house of poor living<br />

standards outside Nettletown, in the Bullwinkel Woods.<br />

I need a well-experienced builder to renovate her home<br />

to a more safe design. I hope that you will be able to<br />

complete this project.’<br />

‘Why, um, yes. Certainly!’ Joe was astounded. A job offer,<br />

finally! He was ecstatic!<br />

‘I’ll email you the address now. I shall contact you later<br />

this week to sort out any complications.’<br />

Then the call ended. Joe placed down the phone, still<br />

dazed by the brilliant situation. He picked up the phone<br />

again to tell his friends of the good news.<br />

***<br />

The old house creaked and moaned against the relentless<br />

wind. Inside, however, the room was dimly lit by an open<br />

fireplace. Two figures sat opposite each other on well-worn<br />

armchairs. Eventually, one of them broke the silence.<br />

20

BENCHMARK<br />

Write-a-Book-in-a-Day<br />

An excerpt from<br />

Terror Amongst the Trees continued<br />

‘Aunty, you really cannot continue to live here. The walls<br />

are old and weathered and the floorboards have become a<br />

safety hazard,’ Gerald insisted.<br />

‘Nonsense, dear, I’m perfectly happy here and have no<br />

intention of moving,’ Elizabeth responded, ‘Besides, your<br />

uncle and I have lived here for many years now, longer<br />

than you’ve been alive, and nothing has ever happened<br />

to us in that time.’<br />

‘Albert has been dead for 15 years now.’<br />

‘He still lives here, you know. He keeps me company<br />

sometimes.’<br />

There was a long silence. Nothing could be heard except<br />

for the crackle of the fireplace. Shadows shimmered in<br />

and out of focus on the peeling walls. Outside, the<br />

gnarled branches of a tree scratched against the frosted<br />

glass of the window pane. A wolf howled in the distance.<br />

The low buzz of cicadas enveloped the quiet room. Finally,<br />

after much contemplation, the nephew spoke.<br />

‘We need to renovate this house. Perhaps some concrete<br />

beams could secure the roof …’<br />

‘Fiddlesticks! You simply don’t understand. This house<br />

means more to me than it does to you or that silly wife<br />

of yours. Modern replacements would wreck this<br />

wonderful home.’<br />

‘I’m afraid the matter has already been settled. I’ve<br />

contacted a bricklayer to strengthen your foundations.’<br />

‘That’s preposterous, dear! I simply won’t allow it. These<br />

modern bricks will wreck the atmosphere of this place.’<br />

‘I shall hear no more of the subject. Like I said, a bricklayer<br />

has been contacted and should arrive later this week. I do<br />

hope that you’ll be accommodating; he may need to stay<br />

the night.’<br />

21<br />

The young man got up to leave, then turned around.<br />

‘Of course any time you would consider moving to a<br />

retirement village I would be only too happy to help.’<br />

Then he left, leaving Elizabeth bewildered.<br />

Hal Crichton-Standish, Blake Bullwinkel, Laurence Nettleton,<br />

Jack Mowbray, Christopher Christian, Joseph Rossi<br />

Year 8 Team – Mentos in Coke

CREATIVE WRITING<br />

Write-a-Book-in-a-Day<br />

An excerpt from<br />

The Lecture<br />

‘That’s all for today. Tomorrow we’ll go over prevention<br />

of tooth decay and gum disease,’ the professor announced,<br />

adjusting his glasses upon his nose. The room let out a<br />

collective sigh of relief after a two-hour lecture.<br />

Sarah’s hand was sore from intense note taking. It wasn’t<br />

that Sarah didn’t enjoy her dentistry course; in fact she<br />

was really passionate about her studies, but hours upon<br />

hours of studying plaque had taken its toll. She was also<br />

unbelievably hungry. Her stomach was groaning and<br />

growling, pleading for food.<br />

After packing her books and returning her glasses to their<br />

case, she left the lecture hall. An animated group of girls,<br />

whom she had met a few days earlier, asked her if she<br />

wanted to grab a drink after the lecture. However she was<br />

too tired, and rejected the offer. She preferred to spend<br />

some nights alone and returned to her college room.<br />

A strong wind was building and Sarah swept the brown<br />

hair from her face. She held her books to her chest,<br />

providing warmth and a wind barrier. Her tired eyes had<br />

lost their usual blue glow, and had sunk into her head.<br />

Small red pimples had found a home on her forehead and<br />

cheeks. Late nights and little sleep were evident in her<br />

physical features.<br />

As she made her way across the university grounds, she<br />

noticed a threatening dark cloud on the horizon. It<br />

seemed to be growing in the sky as she approached the<br />

quadrangle. As she drew nearer to the quad, she noticed<br />

all the usual university activities in full flight. There were<br />

a few guys kicking a hacky sack, an alternative-looking<br />

guy playing the bongos and some couples holding hands<br />

and lovingly staring into each other’s eyes. This typical<br />

university behaviour was to be expected. What was<br />

unusual about the scene was the fact that a peculiar<br />

individual was standing on a bench, as if giving a sermon<br />

to an invisible crowd.<br />

‘I am Father Charles McGregor and I speak to you! The<br />

rapture is imminent! I have seen the way and the way is<br />

with me! Tomorrow a greater power will descend on us!<br />

Join and you will be saved! Follow the Way and you will<br />

be forgiven! Follow the Way and you will be saved from<br />

the impending doom!’<br />

He dressed top to toe in a creaseless white garment. A<br />

rugged beard flowed from his chin. He was the spitting<br />

image of one’s depiction of God. His voice echoed in the<br />

compounds of the quadrangle. A pile of leaflets stood at<br />

his feet. He was handing them out to passers-by who took<br />

one look before discarding them into the nearest bin.<br />

At first Sarah was taken aback by the unusual presence of<br />

this man. Of course, this was not an everyday occurrence<br />

in the university. Despite this, crazy people did crop up on<br />

the campus from time to time, so anything this guy said<br />

should only be taken lightly. Sarah dismissed the preacher<br />

and continued back to her dorm.<br />

***<br />

After showering, Sarah made her way to the empty dining<br />

hall to satisfy her hunger. She was too hungry to care<br />

about the quality of the meal. For the third time this week,<br />

the college chefs had prepared a hearty beef stroganoff for<br />

dinner. She took a plate of the brown mess with rice and<br />

didn’t bother to question where it came from. After a<br />

quick glance around the hall Sarah couldn’t find any of<br />

her friends, so she decided to retreat to her own room.<br />

She didn’t feel like being social anyway.<br />

The journey back to her dorm took her through the<br />

courtyard. From there she could see the dark cloud<br />

brewing, nullifying the sun and casting a foreboding<br />

shadow on the university buildings.<br />

Sarah let herself into her room and collapsed on her small<br />

bed and turned on her miniature television set. She flicked<br />

through the channels and upon finding nothing even<br />

slightly entertaining, settled for the local news broadcast.<br />

The anchors presented the mundane evening news,<br />

starting with a road accident that caused a major traffic<br />

backlog. He then continued on to sport, business and<br />

finally weather. Sarah was drifting off now, catching<br />

fragments of the report as the need for sleep began to<br />

overcome her.<br />

‘Strong wind … Dangerous storm … Unpredictable<br />

conditions are to be expected ...’<br />

That was the last she heard before she was enveloped by a<br />

dream filled sleep.<br />

Mackenzie Baran, Jonathan Li, Jack Rathie, Lewis Cooksley,<br />

Anthony McDougall<br />

Year 10 Team – Dragon Warriors 2<br />

22

BENCHMARK<br />

Jarrah<br />

In a European-dominated school in outback Australia, an<br />

aboriginal boy takes refuge behind a water tank. Regularly<br />

persecuted because of his race, he increasingly retreats into his<br />

own imaginary world. A chance encounter with another boy,<br />

bullied because of his religion, sparks the most unlikely<br />

friendship.<br />

47 Ext – watertank – day<br />

Jarrah runs into shot. We hear boys shouting in the<br />

distance. As the voices fade Jarrah wipes a tear from his<br />

eye. He leans with his back against the water tank and<br />

dejectedly slides down the side of the tank onto the<br />

ground. He wraps his arms around himself and rocks<br />

back and forth. Beads of sweat trickle down his face as<br />

he remembers the previous events.<br />

CALLUM: He doesn’t belong here …<br />

GEORGE: Can’t even speak properly …<br />

HENRY: Should’ve stayed in the bush.<br />

We hear the ticking of a clock to symbolise time passing.<br />

Voices can be heard outside.<br />

TEACHER: Where is he? You say he ran past the<br />

classrooms, then where?<br />

CALLUM: Who cares, he’s a stupid loser anyway.<br />

TEACHER: Don’t say that!<br />

CALLUM: You know it’s true!<br />

TEACHER: The principal won’t be happy. If I catch<br />

that boy …<br />

CALLUM: He doesn’t belong here, why can’t we get<br />

rid of him?<br />

TEACHER: Just get to class!<br />

We hear the sound of footsteps and the voices dissipate<br />

into the distance. Jarrah curls up into a ball. We hear the<br />

clock again, getting louder and louder …<br />

48 Int – foster home kitchen – evening<br />

Pan across to Marian cooking in the kitchen. She is<br />

a European woman in her fifties with graying hair. The<br />

kitchen is small and under-furnished, but it has a warm<br />

23<br />

feel about it. The door opens in the background and<br />

Jarrah enters with his school bag slung over one shoulder.<br />

Marian puts her cooking pot down and turns to Jarrah<br />

with her hands on her hips.<br />

MARIAN: Well?<br />

JARRAH: Well what?<br />

MARIAN: How was your first day of high school?<br />

JARRAH: Okay. I guess.<br />

He dumps his bag at the front door and is about to head<br />

up the stairs.<br />

MARIAN: Now what have I told you about property<br />

dear?<br />

Jarrah picks up his bag and places it down gently. He then<br />

races up the stairs. Marian shakes her head.<br />

MARIAN: Oh Jarrah. What am I going to do with you?<br />

But she’s smiling to herself.<br />

49 Int – foster home dining room – night<br />

Eight other children around Jarrah’s age sit with him at<br />

the table. Marian takes the seat at the head of the table.<br />

MARIAN: I have some news for you all. I am getting a bit<br />

old for all this volunteer work and have decided to leave<br />

you in the capable hands of Miss Kensington.<br />

DARREL: But you can’t leave! You’ve been here eleven<br />

years!<br />

MARIAN: I know dear, and it’s been lovely looking after<br />

you all. But I can’t look after you forever.<br />

DARREL (Muttering): I bet she’s a witch.<br />

50 Ext – schoolyard – day<br />

Jarrah walks through the school gate. As soon as he enters<br />

the school, five boys come out of the shadows. One of<br />

them is Callum. Callum is a small boy with fiery red hair<br />

and a quick temper. Jarrah tries to ignore them.<br />

CALLUM: So you’ve come back again?<br />

JARRAH: Leave me alone.

CREATIVE WRITING<br />

CALLUM: You shouldn’t be here. This is our school. We<br />

don’t take boys from the foster home.<br />

EDWARD: You’re so pathetic even Marian is leaving the<br />

foster home. She’s gotten sick of you.<br />

JARRAH: Why can’t you just drop it?<br />

CALLUM: Didn’t you hear me, idiot? We don’t take your<br />

type in here. This is our school. It was the same with your<br />

parents, wasn’t it?<br />

Jarrah stops dead in his tracks. Callum senses that he’s<br />

hit home.<br />

CALLUM: They couldn’t keep themselves out of other<br />

people’s business. No wonder they were bludgeoned; they<br />

shouldn’t have come to our church.<br />

Jarrah slowly turns around and faces Callum, clenching<br />

his fists. Callum’s friends encircle the two and a chant<br />

begins. Jarrah runs at Callum and punches him in the gut.<br />

Callum is winded.<br />

CALLUM: Stupid … abo …<br />

HENRY: Get him!<br />

The four boys close in on Jarrah, but he slips through<br />

their closing net. He runs behind the classroom block and<br />

his pursuers lose his trail. He races behind the water tank<br />

without being seen.<br />

51 Ext – watertank – day<br />

Safe behind the water tank, Jarrah begins to cry. Silently,<br />

his small body shakes uncontrollably. Callum’s voice<br />

echoes in his head.<br />

CALLUM: … They couldn’t keep themselves out of other<br />

people’s business … … they shouldn’t have come to our<br />

church …<br />

Close up on Jarrah’s eyes, smudged with tears.<br />

FLASHBACK SCENE: Jarrah’s parents laughing,<br />

holding hands.<br />

FLASHBACK: Jarrah going on picnics with his parents.<br />

FLASHBACK: Waving, as they went off to church that<br />

fateful Sunday.<br />

FLASHBACK: Television headlines the day after they died.<br />

NEWSREADER: An aboriginal family was bludgeoned<br />

to death with a crowbar due to a fierce argument …<br />

Jarrah slips into a state of semi-consciousness.<br />

Fade to an image of a bloodied crowbar on the pavement …<br />

Hal Crichton-Standish<br />

Year 8<br />

24

BENCHMARK<br />

The Watcher<br />

All there was, all there had ever been, was the window.<br />

The dripping concrete walls, the white bathroom, the iron<br />

door from which his food and his nightmares came, were<br />

irrelevant, artificial, unchangingly fake. Though this was<br />

all he could touch or move through physically, it was the<br />

world in the window that was the source of all his<br />

thoughts. Looking down upon the world that was outside<br />

the room and the tower, he watched the twisting, erratic<br />

lives of the people below. He understood that once he had<br />

been one of them, and the thought brought tears of<br />

longing to his eyes.<br />

His view of the world below was limited. He could not<br />

hear the people speak or see them when they went into<br />

buildings, save when he saw them through their windows.<br />

Understanding the purpose of their daily movements only<br />

grew more confusing the more he followed their daily<br />

lives. At first they simply seemed to move in and out of<br />

vehicles and buildings, never for any apparent purpose.<br />

After a while though, he saw that individual people<br />

followed a nearly identical pattern each day. Most would<br />

emerge from the same vehicle, enter the same building at<br />

the same time each morning and sit by the same window<br />

each day, before departing each evening for areas<br />

unknown. The reason for these routines was impossible to<br />

determine, and the small variation in behaviour puzzled<br />

him further. Yet the first decision he ever remembered<br />

making was that one day he would understand these<br />

people below him.<br />

Much of their behaviour was explained when he learnt to<br />

read. He could at first gain no meaning from the strange<br />

symbols that covered the outside world but, over the<br />

course of several months he realised there were<br />

connections between certain sequences of characters and<br />

the picture on billboards and shopfronts. After that<br />

teaching himself was easy. He would read newspapers or<br />

books over the shoulder of people in the streets. He never<br />

gave thought to his ability to distinguish the small text on<br />

the pages of the book 100 storeys below, or the fact that<br />

he could read an entire page with a glance whilst the<br />

readers below would stare at a page for several minutes,<br />

just as he never gave thought to what was in the grey soup<br />

that appeared through a slit in the iron door every day.<br />

25<br />

What he did think about was how much more he could<br />

understand through reading. He learnt so many new<br />

words and their meanings, how they related to the<br />

seemingly pointless routines of those below. He learnt<br />

about jobs and money and work. One interesting word<br />

that kept popping up was freedom. He learnt about that<br />

when he saw the two sign-wielding mobs converge on<br />

each other in the park. They seemed to be very angry<br />

and were shouting at each other. Both groups seemed to<br />

believe that the other was trying to take away their<br />

freedom, and they all considered freedom to be very<br />

important. It seemed that freedom was the ability to do<br />

what one wanted, when one wanted. So it confused him<br />

when, after the riot, everyone returned to following the<br />

exact same daily routine they had before; it seemed to<br />

defeat the point of all the shouting and waving of signs<br />

for the sake of freedom.<br />

The first of the nightmares came when he was five years<br />

old. Faceless men in white coats came through the iron<br />

door and dragged him, screaming, down the white<br />

corridors beyond. When they arrived at the glass room he<br />

was tied down to a table. The men in white coats attached<br />

tubes and machines to his body and the world disappeared<br />

into a whirlwind of shocks, lights and pure pain.<br />

He was never sure if the nightmare echoed something that<br />

had actually happened all he knew was that from then on<br />

he could follow people beyond where he could before. His<br />

eyes followed them into buildings and watched them<br />

through the walls of their homes. He saw all. There was<br />

so much that went on behind walls. He learnt of families,<br />

of work and of sex. Each explained a lot that had<br />

previously confused him about the behaviour of the<br />

people outside. Yet, at the same time, it made the world<br />

below even more complex and difficult to understand.<br />

Why did the woman who worked from dawn to dusk in<br />

the highest offices, wearing a bright smile and beautiful<br />

clothes, break into tears every time she stepped through<br />

the door of her empty apartment? Why did the man who<br />

rode the garbage-collecting truck every morning and who<br />

waited outside the shopping centre in uniform with his<br />

head hung every night, suddenly gain a spring in his step<br />

the moment he saw his children?

CREATIVE WRITING<br />

He could now hear them too. It was difficult, often, to<br />

find interesting talk over the incessant buzz of millions<br />

of people gossiping about nothing but he found that the<br />

more serious and interesting conversations, few as they<br />

were, were generally had privately, and sounded generally<br />

more hesitant, as if talking about something serious was<br />

something to be ashamed of. He also learnt the power<br />

words had over people. Over several weeks he saw a man<br />

beat a woman each night, each night she picked herself<br />

off the ground, seemingly unchanged. One night he heard<br />

her speak, screaming words like ‘failure’ and ‘nothing’.<br />

The man had turned without a word, ascended the<br />

stairwell of their apartment building and flung himself<br />

from the roof. Then there was the young olive-skinned<br />

girl in the headscarf who laughed when she spoke and<br />

skipped when she walked until she first came to one of<br />

the buildings the people called schools. The Child in the<br />

tower heard taunts of ‘Paki’ and ‘terrorist,’ follow her<br />

through the day. He never saw her laugh again.<br />

The second nightmare came three years after the first.<br />

Once more the figures in white coats took him through<br />

the iron door. This time the glass room was occupied<br />

by a great whirring machine in which was embedded a<br />

chair. Remembering the pain of before he struggled and<br />

scratched and bit at the men, but they would not let go,<br />

and forced him into the chair. As the machine began to<br />

move around him he started to hear whispers coming<br />

from everywhere and nowhere. He looked out but the<br />

men in white coats had their lips sealed. The whispering<br />

grew louder until it screamed through his mind, blotting<br />

out everything. Yet each individual whisper sounded no<br />

louder than it had before. It was like more and more tiny<br />

voices were beginning to speak, asking for something,<br />

anything, but he could not hear what. After the whispering<br />

came the feeling and it was like nothing else in the world.<br />

Each whisper came with an emotion, a taste, and as he felt<br />

them he understood them. Longing, despair, pity, sadness,<br />

hope-ambition-anger-joy-jealousy-lovehatesatisfactionlustfearcarewantdisgusthelplessnessavaricealienation<br />

… It was<br />

too much. The last thing he saw before he fell into blissful<br />

nothingness were the burning, black eyes of one of the<br />

men in white coats, the last whisper he heard was, ‘Soon.’<br />

When he woke in his room, deathly cold and aching, the<br />

whispering and feeling still remained, just weaker. When<br />

he looked down from the window he found that it was the<br />

people below who were whispering. Whispering without<br />

moving their lips, even as they said aloud something<br />

completely unlike what they whispered, whilst their<br />

emotions rose from them like a scent.<br />

He understood. This was what was in each person’s<br />

mind. That was when he knew the world was wrong.<br />

The people’s spoken words rarely, if ever, matched the<br />

whispers and the feelings. It was clear too that no one<br />

knew what they wanted, let alone what would make<br />

them happy. All around him he felt warm sparks of love,<br />

contentment, resolve or hope rise up, only to disappear<br />

with the reading of a report from a teacher, a conversation<br />

with an employer, a phone call from a lover, a headline in<br />

the papers or an announcement from a judge. And there<br />

were so many who were just so wrong in what they<br />

thought they wanted. Office workers infuriated him. Each<br />

person had a feeling of something missing, and believed<br />

they could find it in one of the offices on the floor above.<br />

The strange thing was, those in the offices above felt<br />

exactly the same about the offices above them, only<br />

the feeling of emptiness seemed for the most part even<br />

stronger. He did not like looking into the hearts of the<br />

men who sat at the long tables at the top of the office<br />

towers. They were completely empty, often cruel or<br />

miserable; and seemed to want to eat everything. And yet<br />

everyone below them seemed desperate to become like<br />

them. The boy in the tower pitied these people the most.<br />

Yet they were everywhere, sucking the life from<br />

themselves and others; in the offices, in homes, in the<br />

parliament building, everywhere.<br />

On 21 December in the year 2012, at dawn, the boy in<br />

the tower had a visitor. The iron door opened once more.<br />

The Child was not afraid; he had felt the fear of billions<br />

and knew what was worth fearing and what was not. The<br />

man with the black eyes greeted him. The Child heard<br />

every thought in his head before he said it. The man<br />

spoke with the feverish excitement of one whose entire life<br />

had been dedicated to that moment. ‘You understand now,<br />

why we did this to you? We needed someone who saw<br />

what we saw even more clearly than we did, one who<br />

26

BENCHMARK<br />

The Watcher continued<br />

could find the answer. The world is broken, and must be<br />

fixed. Do you know what must be done?’ The Child<br />

looked down on the suffering world below him and for<br />

the first time in his life, he spoke. His voice was like a<br />

great crowd speaking in unison, telling of an end and a<br />

beginning, radiating terrible knowledge and an utter,<br />

terrifying power. The man with the burning black eyes<br />

shivered as a single word reverberated through the room,<br />

shattering every window, reducing the iron door to dust.<br />

‘Yes.’<br />

Nick Pether<br />

Year 11<br />

27

CREATIVE WRITING<br />

The Unseen Foe<br />

Amun turned his head from the harsh sting of the desert<br />

wind, his dark, powerful legs shifting painfully in the<br />

sand with each laboured step he took. Sucking the dry<br />

air through his coarse tunic, relief overcame Amun as the<br />

steady rattle of heavily laden saddles finally ceased, the<br />

weary camels squatting in the golden sand to let down<br />

their riders and rest what were undoubtedly exhausted<br />

legs. Slumping to the ground like the animals, Amun<br />

emptied the last of what had once been a bulging<br />

waterskin into is mouth, his parched throat throbbing<br />

with pain as he swallowed and observed the other men.<br />

Garbed in the dark blue robes of the royal warriors, the<br />

eight men stood tall; black silhouettes against the distant<br />

sun, their ghostly shadows streaked across the desert as<br />

they exchanged glances, waiting grimly by their respective<br />

animals. Only one camel remained on its feet, its golden<br />

saddle glinting with the touch of loose rays of sunlight, its<br />

rider perched seemingly motionless atop its humped back.<br />

Engrossed by what appeared to be a thin, tattered scroll<br />

and its miniscule glyphs, the King’s eyes scanned the page<br />

with intense fixation, as if searching for some crucial<br />

detail he’d missed the last million times. Comparing the<br />

gaping, stone entrance to one of the faded symbols, the<br />

King dismounted, smiling as he rolled the fragile paper<br />

up for the first time in many days.<br />

The life of a slave was not, traditionally, an adventurous<br />

one, and looking back at the vast horizon that extended as<br />

far as the eye could see, Amun was acutely aware of how<br />

far the King’s journey had taken them from the land they<br />

called home. Though the kingdom held little opportunity<br />

for Amun, the familiarity of his simple room and palace<br />

duties were daily comforts he was learning to live without.<br />

As one of the luckier royal slaves, Amun was to be at the<br />

beck and call of the divine Prince, and had seen the<br />

younger man grow up into the strong and admired King<br />

he had become. Although nobody knew with certainty,<br />

some speculated that the King and his leading slave had<br />

developed a relationship, over the course of years, which<br />

was almost akin to friendship. Though merely rumour,<br />

just the notion of befriending a slave, let alone one of dark<br />

skin, was enough to trigger a strong sense of disapproval<br />

amongst various members of the community. Amun was<br />

regularly insulted when the King’s back was turned, and<br />

had long grown to be grateful for his just master’s<br />

unwavering sense of integrity.<br />

Only when thinking back to those days gone by,<br />

remembering the young King and their close friendship,<br />

did Amun appreciate how much had changed as they’d<br />

matured. Despite the King’s broader shoulders and ageing<br />

face, Amun was one of the few to see that the greatest<br />

changes were invisible to the eye, observing his friend on<br />

a daily basis. The signs had been subtle at first: a declined<br />

meal or a sad glance at his reflection. Yet it wasn’t long<br />

before the shroud of mystery was raised from Amun’s eyes.<br />

Known as a great and fearless warrior, it seemed that there<br />

was no foe that struck fear in the heart of the King, but<br />

Amun was astute enough to know that not all foes rode in<br />

speeding chariots, spears brandished high. For some, the<br />

enemy took the form of the setting sun, the passing of<br />

numbered days, and the feeling of time slowly slipping away<br />

like sand in an hourglass. Time was the foe which even the<br />

fiercest warrior and wisest king were subject to; a concept<br />

that Amun could see his friend struggling to accept.<br />

Even as his youth inevitably took flight, the King pursued<br />

it valiantly, remaining impressively fit and perceptive,<br />

while meeting regularly with his healers and priests.<br />

Though the King had been able to slow down the clock,<br />

Amun could see that he knew he was fighting a losing<br />

battle. Though it was not in the nature of their<br />

relationship to talk about such issues, Amun often<br />

wondered if the obsession with youth stemmed from the<br />

absence of children in the King’s life, a respected son or<br />

a beautiful daughter. Though he had held many titles,<br />

‘Father’ had never been one of them. Whatever the source<br />

was, Amun would look into his friend’s eyes more and<br />

more to find defeat, and too often would he hear him<br />

speaking about what would become of the kingdom<br />

without him. Though Amun had seen otherwise, the<br />

King assured him that his worry was for the people and<br />

the future of the kingdom, not for himself. So grew an<br />

increasing curiosity in immortality, and cheating the bite<br />

of death.<br />

Seeing his once lively friend withdraw into himself, Amun<br />

refused to help his master for the first time, as the King<br />

searched the palace archives, uncharacteristically<br />

28

BENCHMARK<br />

The Unseen Foe continued<br />

frantic, for an ancient scroll that promised saviour<br />

from sure doom. Awoken one night, by the echo of a<br />

triumphant cry, Amun’s memory was still burnt with the<br />

image of the deranged King, his crazed eyes wide open<br />

with hungry focus, on his knees, filthy robes sticking to<br />

his clammy skin. His eyes darted across the scroll’s tiny<br />

lines of symbols. The royal warriors had been summoned<br />

at once, to prepare for a journey that was to commence<br />

the next morning.<br />

‘This is it Amun. The solution is within reach,’ the King<br />

said and his voice filled with hope, ‘You must come Amun,<br />

This marks a new era in the kingdom’s history!’<br />

‘I will not, Master,’ replied Amun, his deep voice<br />

brimming with conviction, his heavy brow framing<br />

firm eyes.<br />

‘You will not?’ hissed the King with feigned hurt, ‘I think<br />

you forget your place, Amun.’<br />

‘As a friend, I cannot condone this, Master. That which<br />

you desire can only lead to evil,’ Amun murmured,<br />

disturbed by the mocking tone in his friend’s voice.<br />

‘You misunderstand Amun. You WILL come,’ the King<br />

interrupted bitterly, his bearded face creased with disbelief.<br />

‘Remember you are first my slave, and second my friend,’<br />

he finished dismissively, turning his back on Amun.<br />

Stunned by the King’s outburst, Amun silenced himself,<br />

sensing that this was not the man he had once known and<br />

called brother. The next morning, no warm citizens, or<br />

grand spectacles saw them off, but only the dappled light<br />

of the rising dawn sun. The company of ten left in secret,<br />

a silent string of camels disappearing into the distance on<br />

the scroll’s bearing. Unworthy to command his own steed,<br />

Amun had grudgingly agreed to take turns riding with<br />

the warriors, silently wondering what was in store for<br />

the company.<br />

Woken from memory by the sharp whistle of a muscular<br />

solider, Amun raised himself from the sand, steadying<br />

himself on a nearby camel as he saw the King take the<br />

first step into the ominous, columned entrance.<br />

29<br />

‘You will stay here mud-skin!’ the solider barked cruelly, as<br />

Amun also began to walk towards the entrance. ‘Stay with<br />

the animals, where you belong.’<br />

Ignoring the insults, Amun obeyed the order, waiting<br />

until the glow of torches had completely disappeared<br />

into the blackness before pursuing them with tired legs.<br />

Padding into the recess, the rough, stone ground was cold<br />

and hard against Amun’s bare, calloused feet, as he<br />

followed the echo of men’s voices. Turning a corner,<br />

Amun saw light appear as the narrow tunnel arced out<br />

into a vast, empty cavern. Cutting the blackness, a wide<br />

beam of light cascaded from what must have been a hole<br />

at the top of the chamber, illuminating a small silver altar<br />

which the King and royal warriors approached, dropping<br />

their torches. Tempted to emerge from the shadows,<br />

Amun controlled the impulse, muscles tensed as he waited<br />

to see what would unfold. As the blue warriors backed<br />

away, the King approached the altar slowly and seized<br />

the small, shining orb that floated above it. His eyes filled<br />

with blatant awe, the King gazed into the orb, his<br />

reflection distorted by his desires as he looked into the<br />

eyes of a younger version of himself.<br />

‘Youth,’ the King said, the word barely floating from his<br />

open mouth as the orb began to glow, its light reflected in<br />

his glazed eyes.<br />

Amazed, Amun watched on speechlessly as the orb burned<br />

with the intensity of the sun, filling the vast cavern with<br />

bright, golden light. As a current of wind began to circle<br />

around him, the King could feel warmth spreading<br />

through his body, as he felt the weight of age lift from his<br />

shoulders. Overcome with astonishment, Amun barely<br />