Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

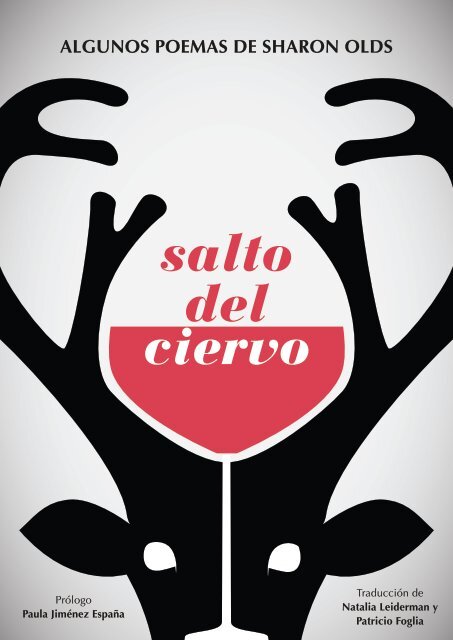

ALGUNOS POEMAS DE SHARON OLDS<br />

<strong>salto</strong><br />

<strong>del</strong><br />

<strong>ciervo</strong><br />

Prólogo<br />

Paula Jiménez España<br />

Traducción de<br />

Natalia Leiderman y<br />

Patricio Foglia

Noviembre, 2016<br />

Buenos Aires, Argentina<br />

“Stag´s Leap” de Sharon Olds, 2012<br />

Traducciones: Natalia Leiderman / Patricio Foglia<br />

Edición y correción: Natalia Leiderman / Patricio Foglia<br />

Edición y maquetación: Alfredo Machado<br />

Arte de tapa y diseño editorial: Alfredo Machado

<strong>salto</strong><br />

<strong>del</strong><br />

<strong>ciervo</strong>

05<br />

PRÓLOGO<br />

Paula Jiménez España<br />

08<br />

NOTA DE TRADUCCIÓN<br />

Natalia Leiderman - Patricio Foglia<br />

09<br />

TRADUCCIONES<br />

13<br />

14<br />

15<br />

16<br />

17<br />

18<br />

19<br />

20<br />

23<br />

24<br />

27<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> <strong>ciervo</strong> (2012)<br />

Locos<br />

El atril<br />

Lo peor<br />

Innombrable<br />

A último momento<br />

Los curanderos<br />

Gazal <strong>del</strong> moretón<br />

Ser la que fue dejada<br />

Una cosa secreta (2008)<br />

Todo<br />

Diagnóstico<br />

El cuarto sin barrer (2002)<br />

Domingo en<br />

el Nido Vacío<br />

37<br />

38<br />

39<br />

43<br />

44<br />

47<br />

51<br />

52<br />

53<br />

La fuente (1997)<br />

Primeras imágenes <strong>del</strong> cielo<br />

Me encanta cuando<br />

Plegaria de aquella época<br />

El padre (1992)<br />

Su quietud<br />

La mirada<br />

La celda de oro (1987)<br />

Solsticio de verano,<br />

ciudad de New York<br />

Los muertos y los vivos (1983)<br />

Muerte de Marilyn Monroe<br />

La ausente<br />

Para mi hija<br />

31<br />

32<br />

33<br />

34<br />

Sangre, lata, heno (1999)<br />

Cuando te viene<br />

La niñera<br />

Una vez<br />

Estos días<br />

57<br />

58<br />

59<br />

60<br />

Satán dice (1980)<br />

Ese año<br />

Es tarde<br />

Ahogándose<br />

Satán dice

63<br />

VERSIONES EN INGLÉS<br />

67<br />

68<br />

69<br />

70<br />

71<br />

72<br />

73<br />

74<br />

77<br />

78<br />

81<br />

Stag’s leap (2012)<br />

Crazy<br />

The easel<br />

The worst thing<br />

Unspeakable<br />

The last hour<br />

The healers<br />

Bruise Ghazal<br />

Known to be left<br />

One secret thing (2008)<br />

Everything<br />

Diagnosis<br />

The unswept room (2002)<br />

Sunday in<br />

the Empty Nest<br />

91<br />

92<br />

93<br />

97<br />

98<br />

101<br />

105<br />

106<br />

107<br />

The wellspring (1997)<br />

Early images of heaven<br />

I love it when<br />

Prayer during that time<br />

The father (1992)<br />

His stillness<br />

The look<br />

The gold cell (1987)<br />

Summer solstice,<br />

New York City<br />

The dead and the living (1983)<br />

Death of Marilyn Monroe<br />

Absent one<br />

For my daughter<br />

85<br />

86<br />

87<br />

88<br />

Blood, tin, straw (1999)<br />

When it comes<br />

The babysitter<br />

Once<br />

These days<br />

111<br />

112<br />

113<br />

114<br />

Satan says (1980)<br />

That year<br />

Late<br />

Drowning<br />

Satan says

la diabla<br />

/Por Paula Jiménez España<br />

¿Cómo se presenta a un autor, una autora? Patricio Foglia y Natalia<br />

Leiderman, compiladores, eligieron hacerlo invirtiendo cronológicamente el<br />

historial bibliográfico de Sharon Olds, quizás con la intención, nada ingenua,<br />

de generar esta impresión ni bien arranca nuestra lectura: los años no convertirán<br />

jamás a esta norteamericana nacida en San Francisco en 1942 – que<br />

entre otras cosas, publicó ocho libros igualmente tremendos y le negó una<br />

cena a Laura Bush-, en una anciana piadosa.<br />

La presente antología comienza con algunos de los poemas que integran Salto<br />

<strong>del</strong> <strong>ciervo</strong> (2012), <strong>del</strong> cual toma su nombre, y continúa con el resto de las publicaciones<br />

hasta regresar a su mítico Satán dice (1980), que no fue solo el<br />

primer libro de Olds sino también la piedra fundacional de una poética cruda<br />

y oscuramente potente. Pasaron, a partir de la aparición editorial de Satán<br />

dice, treinta y seis años – Sharon tenía 38 – y no se puede decir que desde entonces<br />

su poética se haya suavizado; no se puede decir que aquel gesto irreverente<br />

de los comienzos respondiera solamente a las urgencias y enojos frente<br />

a las imposiciones sociales, familiares e incluso lingüísticas, tantas veces presentes<br />

en los primeros libros de cualquier autor. “Decí mierda, decí muerte,<br />

decí a la mierda el padre/ me dice Satán al oído. / El dolor <strong>del</strong> pasado encerrado<br />

zumba/ en la caja de la infancia en su escritorio, bajo/ el terrible ojo esférico<br />

<strong>del</strong> estanque/ con grabados de rosas a su alrededor, donde/ el odio a ella<br />

misma se contempla en su pena. / Mierda. Muerte. A la mierda el padre. / Algo<br />

se abre. Satán dice/ ¿No te sentís mucho mejor?”, escribió en uno de aquellos<br />

poemas que marcaron la dirección de un discurso poético incorrectísimo <strong>del</strong><br />

que jamás se retraería (por supuesto que otra cosa que jamás se retrajo fue el<br />

rechazo a su obra por parte de muchos críticos norteamericanos pese a que<br />

libros suyos como El padre hubieran adquirido resonancia mundial u obtenido<br />

premios como el Pullitzer, The San Francisco Poetry Center Award, el Premio<br />

Lamont, The National Books Critics Circle Award y el Premio T. S. Eliot).<br />

La intensidad de las escenas construidas en sus versos y la agudeza e irreverencia<br />

con que Olds encara sus tópicos preferenciales (la sexualidad y la<br />

muerte), la ponen en la línea poética de otras chicas norteamericanas igualmente<br />

“revulsivas”, como Sylvia Plath, Adrianne Rich o Muriel Rukeyser, con<br />

quien estudió en Nueva York y a la que le dedicó uno de los textos más bellos<br />

de Los muertos y los vivos (1983), incluido en esta antología; se llama La<br />

ausente y dice así: La gente te sigue viendo/ y me cuenta /lo blanca que estás,<br />

lo flaca que estás. /Hace un año no te veo, pero/ lentamente estás / apareciendo<br />

sobre mi cabeza, blanca como/ pétalos, blanca como leche, los oscuros/<br />

angostos tallos de tus tobillos y tus muñecas, / hasta que estás/ siempre conmigo,<br />

una floreciente/ rama suspendida sobre mi vida.<br />

05

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

Por cómo salió al ruedo literario podría decirse que la entonces señorita Olds<br />

defendió a ultranza su voz, sacando a la luz, de primera instancia, una poética<br />

tan cuidada como desafiante. A lo largo de la lectura de esta antología puede<br />

inferirse que algo de aquella ira satánica inicial fue “aplanada a la fuerza” -<br />

como dice S. en 2012 para referirse al amor pasional y los años-, como son<br />

aplanados los impulsos corporales con el tiempo, en la misma proporción. Sus<br />

últimos libros, tanto Salto <strong>del</strong> <strong>ciervo</strong> como Una cosa secreta, dan cuenta de<br />

una decadencia física a partir de la cual la palabra se reviste de otro tipo de potencia,<br />

menos enérgica en un sentido, pero igual de maldita, visiblemente más<br />

certera y corrosiva: “Adentro mío ahora/ hay un ser de puro odio, un ángel/ <strong>del</strong><br />

odio. En la cancha de bádminton, ella lanza/ su tiro ganador, puro como una<br />

flecha,/ mientras por los ojales de mi blusa las chinches/ pican una carne que<br />

ya no parece/ importarle a nadie. En el espejo, mi torso /parezco una sex–symbol<br />

mártir, llena de picaduras,/ o una jarra de crema con hojas de ortigas y<br />

flores <strong>del</strong> desierto, / llena de leche de la bondad y la maldad/ humanas, y nadie<br />

está haciendo la fila para tomarla./¡Pero miren! ¡Estoy empezando a resignarme!/<br />

Creo que ya no va a volver. Algo/ muere, adentro mío, cuando pienso en<br />

esto,/ como la muerte de una bruja en la cama/ mientras nace un bebé en la<br />

cama de al lado. Ten fe, /viejo corazón. Qué es vivir, de todas formas,/ sino<br />

morir”, dice en el poema de título fatal Ser la que fue dejada. Y si digo que es<br />

fatal, es sobre todo teniendo en cuenta que el feminismo atravesó desde el comienzo<br />

su obra, buscando liberarla de las cadenas que atan a la elección de<br />

un lenguaje y un imaginario neutrales y sumisos al poder patriarcal. Ser la que<br />

fue dejada es, sin duda, un título irónico que muestra hasta dónde una frase<br />

vulgar se hace carne incluso en un cuerpo que ha combatido los lugares comunes,<br />

las trampas discursivas, los estereotipos debilitantes de las mujeres. En<br />

estos versos, Sharon muestra el corazón <strong>del</strong> horror que es el odio a sí misma y<br />

hacia una igual (un odio que es algo más que eso y que está presente en algunos<br />

poemas referidos a su madre, algunos de ellos en el límite con lo incestuoso.<br />

Esos mismos sentimientos aparecen en poemas dedicados a su padre).<br />

Sharon Olds no se acomoda, no agacha la cabeza, está dispuesta a encontrar<br />

su dosis de verdad, la verdad que la salva de la humillación, aun si la tiene que<br />

ir a buscar a un lugar en el que ya no es posible cambiar nada: el pasado. En<br />

el poema El atril, también de Salto <strong>del</strong> <strong>ciervo</strong>, dice: “Y qué si alguien me hubiera<br />

dicho, treinta/ años atrás: Si renunciás, ahora, / a tu deseo de ser una artista,<br />

puede que él / te ame toda la vida – ¿cuál hubiera sido / la respuesta? Ni siquiera<br />

tenía poemas, / nacerían más tarde de nuestra vida familiar –/ qué podría<br />

haber dicho: nada, nada va a detenerme”. Y, efectivamente, nada la detuvo. El<br />

resultado es esta flecha que lanzada hacia<br />

06

atrás va a recoger algunas de sus perlas más memorables: versos que dinamitan<br />

la tranquilidad <strong>del</strong> bien pensante, burlas a quien se dispone a leer poesía para<br />

encontrar en la lírica un bálsamo. Pero aún quienes vamos a buscar lo que ella<br />

tiene para ofrecernos, hay momentos en que también damos con lo insoportable,<br />

como en el poema La niñera de Sangre, lata, heno (1999), donde poetiza<br />

una de los momentos más impresionantes de su obra (ya sé qué es difícil determinar<br />

ese rango): “No sabía realmente qué era una persona, yo/ quería que<br />

alguien me chupara el pezón, / terminé encerrada en el baño, / desnuda hasta<br />

la cintura, sosteniendo a la bebé, / y lo único que ella quería eran mis anteojos,<br />

la sostuve/ suavemente, esperando que tomara la decisión,/ como un angelito,<br />

con su enfermera. Y ella no quería, sólo quería/ mis anteojos. Chupá, carajo,<br />

pensé, /quería sentir el tirón de otra /vida, quería sentirme necesaria”.<br />

Queda claro porqué para muchos y muchas, hablar de Sharon Olds es hablar<br />

de una poeta “confesional”. Pero personalmente creo que lo suyo es, más bien,<br />

lo inconfesable: más que por el arrepentimiento o la catarsis propios de la confesión,<br />

lo que producen determinados versos es una especie de tentación morbosa<br />

ante lo prohibido, lo que “no debería decirse”. Por momentos, no podemos<br />

dejar de leer aquello que nos desagrada (recuerdo haberme preguntado<br />

más de una vez mientras leía un poema suyo hasta donde pensaba llegar). Y<br />

nos desagrada porque contiene una verdad que sería preferible ser mantenida<br />

en sombras para cualquier mortal; una verdad que busca iluminarse y que<br />

como una enredadera a una pared se agarra <strong>del</strong> poema para tomar una forma<br />

estética y visible. El poema es entonces funcional, una herramienta para desencarcelar,<br />

un medio que se convierte, sin embargo, gracias a la genialidad de<br />

Sharon, en el propio fin.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

La selección de la presente antología, gracias al criterio de los jóvenes traductores<br />

y poetas Foglia y Leiderman, muestra lo peor y lo mejor de Olds, que en<br />

su poesía es una sola cosa, un monstruo de dos cabezas. Siguiendo las huellas<br />

de su espíritu nunca manso y lo descarnado de sus imágenes, los curadores la<br />

presentan sin atenuantes, comenzando por el desgarro de los últimos años<br />

donde el decir poético alcanzó una expresión más sutil y a la vez madura,<br />

aunque igual de maledicente. Respecto <strong>del</strong> tiempo, lo mismo sucede en las<br />

pampas que en San Francisco: una diabla sabe por diabla, pero por vieja,<br />

cuánto más.<br />

07

nota de<br />

traducción<br />

/Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo.<br />

Sharon Stuart Cobb, para nosotros Sharon Olds, nació en San Francisco, California,<br />

EEUU en 1942. Se crió en el seno de una familia calvinista, con un<br />

padre alcohólico. De niña, participó y ganó un concurso de canto junto con<br />

el coro de su parroquia. Sus primeras influencias fueron Shakespeare y Whitman<br />

pero, sobre todo, Aullido de Ginsberg. Más cerca de Muriel Rukeyser que<br />

de Anne Sexton o Sylvia Plath, cuando le preguntan por las llamadas poetas<br />

confesionales, contesta: “Eran geniales, y mucho más inteligentes que yo, pero<br />

son huellas en donde prefiero no poner mi pie”. Realizó estudios de grado y<br />

de posgrado, se doctoró con una tesis sobre Emerson y es famoso su pacto<br />

fáustico: ella, en las escalinatas de la Universidad, termina su carrera y se encuentra<br />

con el Diablo. Le pide poder escribir poemas verdaderos. El Diablo<br />

acepta, a cambio de que ella olvide todo lo aprendido. Cuando fue invitada a<br />

la Casa Blanca por la primera dama, Laura Bush, respondió que no asistiría en<br />

una carta que termina de este modo: “Lo que me decidió fue que estaría aceptando<br />

la comida ofrecida por la Primera Dama de la administración que desató<br />

esta guerra (…). Pienso en los limpios manteles de su mesa, en los cuchillos<br />

relucientes y las llamas de los can<strong>del</strong>abros y mi estómago no lo soporta.”<br />

A la fecha, ocho poemarios conforman su obra, que puede leerse como un<br />

ejemplo deslumbrante de una poética que parte de una anécdota personal<br />

para hacer arder las preguntas universales. Este recorrido se articula desde una<br />

voz poderosa, constructora de un espacio femenino, especialmente afilado e<br />

incómodo. Los poemas de Olds parecen estar siempre magnetizados por el<br />

vértigo, precipitándose hacia puntos ciegos, zonas que el imaginario social ha<br />

vuelto invisibles o intransitables. Son éstas las razones que nos motivaron a<br />

contribuir a la traducción de esta poeta al español (más específicamente, al<br />

español rioplatense): la tensión entre placer y revulsión que provoca su lectura;<br />

la exploración de un universo personal en pos <strong>del</strong> <strong>salto</strong> a un universo<br />

común; la feliz expansión <strong>del</strong> horizonte de lo pensable y lo experimentable.<br />

La presente selección de poemas está centrada en el último libro de Olds (El<br />

<strong>salto</strong> <strong>del</strong> <strong>ciervo</strong>) pero procuramos hacer un pequeño recorrido por toda su obra<br />

poética. Consultamos durante este proceso distintas traducciones previas,<br />

especialmente las realizadas por Mirta Rosenberg, Ezequiel Zaidenwerg, Tom<br />

Maver, Sandra Toro, Mori Ponsowy, Ignacio Di Tullio e Inés Garland, todas lecturas<br />

que recomendamos.<br />

Natalia Leiderman - Patricio Foglia<br />

08

de Natalia Leiderman<br />

y Patricio Foglia

<strong>salto</strong><br />

<strong>del</strong><br />

<strong>ciervo</strong><br />

[2012]

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

locos<br />

/Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo, 2012.<br />

Yo dije que habíamos estado locos<br />

el uno por el otro, pero tal vez mi ex y yo no estábamos<br />

locos uno por el otro. Tal vez estábamos<br />

cuerdos uno por el otro, como si nuestro deseo<br />

no fuera ni siquiera personal–<br />

era personal, pero eso apenas importaba, porque<br />

parecía no haber ninguna otra mujer<br />

ni hombre en el mundo. Quizá fue<br />

un matrimonio arreglado, el aire y el agua<br />

y la tierra nos habían concebido juntos – y el fuego,<br />

un fuego de placer como una violencia<br />

de ternura. Entrar juntos en esas bóvedas, como una<br />

pareja solemne o jocosa con pasos<br />

formales o con el pelo revuelto y a los gritos, se pareció a<br />

los caminos de la tierra y la luna,<br />

inevitables, e incluso, de algún modo,<br />

tímidos– encerrados en una timidez juntos,<br />

en igualdad de condiciones. Pero quizá yo<br />

estaba loca por él – es verdad que veía<br />

esa luz alrededor de su cabeza cuando yo llegaba tarde<br />

a un restorán – oh por Dios,<br />

estaba extasiada con él. Mientras tanto los planetas<br />

se orbitaban los unos a los otros, la mañana y la noche<br />

llegaban. Y quizá lo que él sintió por mí<br />

fue incondicional, temporal,<br />

afecto y confianza, sin romance,<br />

pero con cariño – con cariño mortal. No hubo<br />

tragedia, para nosotros, hubo<br />

una comedia cautivante y terrible<br />

revelada de a poco. Qué precisión se hubiera necesitado,<br />

para que los cuerpos volaran a toda velocidad por<br />

el cielo tanto tiempo sin lastimarse el uno al otro.<br />

13

el atril<br />

/Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo, 2012.<br />

Cuando enciendo el fuego, me siento útil–<br />

orgullosa de que puedo separar la tuerca<br />

<strong>del</strong> tornillo oxidado, des–<br />

armando una de las cosas que mi ex<br />

dejó cuando me dejó. Y tirar sus<br />

finos, pulidos estantes de madera<br />

sobre la leña, y así alimentar<br />

las corrientes ascendentes–<br />

qué bien. Y entonces, por la luz de la llama,<br />

me doy cuenta: estoy quemando<br />

su viejo atril. Cómo es posible,<br />

después de horas y horas – en total, quizá<br />

semanas, un mes inmóvil – mo<strong>del</strong>ando<br />

para él, nuestros primeros años juntos,<br />

olor a acrílico, tensión <strong>del</strong> lienzo<br />

ya preparado. Estoy quemando la obra que dejó atrás,<br />

él, que fue el primero en transformar<br />

a nuestra familia, desnuda, en arte.<br />

Y qué si alguien me hubiera dicho, treinta<br />

años atrás: Si renunciás, ahora,<br />

a tu deseo de ser una artista, puede que él<br />

te ame toda la vida – ¿cuál hubiera sido<br />

la respuesta? Ni siquiera tenía poemas,<br />

nacerían más tarde de nuestra vida familiar –<br />

qué podría haber dicho: nada, nada va a detenerme.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

14

lo peor<br />

/Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo, 2012.<br />

De un lado de la autopista, las sierras áridas.<br />

Del otro, a la distancia, los restos de la marea,<br />

estuarios, bahía, garganta<br />

<strong>del</strong> océano. No había puesto<br />

en palabras, todavía – lo peor,<br />

pero pensaba que podría decirlo, si lo decía<br />

palabra por palabra. Mi amiga manejaba,<br />

nivel <strong>del</strong> mar, sierras costeras, valle,<br />

estribaciones, montañas – cuesta abajo, para ambas,<br />

de nuestros años de juventud. Yo había estado diciendo<br />

que apenas me importaba ahora, el dolor,<br />

lo que me preocupaba era – digamos que había<br />

un dios – <strong>del</strong> amor– y yo le había dado– había tenido la intención<br />

de darle– mi vida– a él– y<br />

había fallado– bueno yo podía sufrir por eso y nada más –<br />

pero ¿qué pasaba, si había<br />

lastimado, al amor? Grité furiosa,<br />

y sobre mis anteojos se acumuló el agua salada, casi<br />

dulce para mí, entonces, porque estaba nombrado,<br />

lo peor– y una vez nombrado,<br />

supe que no había ningún dios, solo<br />

personas. Y mi amiga se acercó,<br />

hacia mis manos, que se apretaban una contra otra,<br />

y su palma las frotó, un segundo,<br />

con torpeza, y cortesía<br />

sin eros, con la ternura <strong>del</strong> hogar.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

15

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

innombrable<br />

/Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo, 2012.<br />

Ahora empiezo a mirar el amor<br />

distinto, ahora que sé que no<br />

estoy bajo su luz. Quiero preguntarle a mi<br />

casi–ya–no marido cómo es esto de no<br />

amar, pero él no quiere hablar de eso,<br />

él quiere calma para el fin de lo nuestro.<br />

Y a veces siento como si yo, ahora,<br />

no estuviera acá – estoy bajo su mirada<br />

de treinta años, no bajo la mirada <strong>del</strong> amor,<br />

siento una invisibilidad<br />

como un neutrón en una cámara de niebla<br />

perdido en un acelerador gigante, donde<br />

lo que no se puede ver es inferido<br />

a partir de lo visible.<br />

Después de que suena la alarma,<br />

lo acaricio, mi mano es como una cantante<br />

que canta a lo largo de él, como si fuera<br />

la carne de él la que canta, en todo su registro,<br />

tenor de la vértebra más alta,<br />

barítono, bajo, contrabajo.<br />

Quiero decirle, ahora, ¿Cómo<br />

era amarme –cuando me mirabas,<br />

qué veías? Cuando él me amaba, yo miraba<br />

hacia el mundo como desde adentro<br />

de una profunda morada, una madriguera, o un pozo, yo miraba fijo<br />

hacia arriba, al mediodía, y veía a Orión brillando<br />

– cuando pensaba que él me amaba, cuando pensaba<br />

que estábamos unidos no solo por el tiempo de la respiración,<br />

sino por la larga continuidad,<br />

los caramelos duros <strong>del</strong> fémur y la piedra,<br />

lo inalterable. Él no parece enojado,<br />

yo no parezco enojada<br />

salvo en chispazos de mal humor,<br />

todo es cortesía y horror. Y después<br />

cuando digo, ¿esto tiene que ver<br />

con ella?, él dice, No, tiene que ver con<br />

vos, no estamos hablando de ella.<br />

16

a último momento<br />

/Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo, 2012.<br />

De repente, a último momento<br />

antes de que me llevara al aeropuerto, se levantó,<br />

tropezando con la mesa, y dio un paso<br />

hacia mí, y como un personaje de una de las primeras<br />

películas de ciencia ficción se inclinó<br />

hacia a<strong>del</strong>ante y hacia abajo, y desplegó un brazo,<br />

golpeándome el pecho, y trató de abrazarme<br />

de alguna forma, yo me levanté y nos tropezamos,<br />

y después nos quedamos parados, alrededor de nuestro núcleo, su<br />

áspero llanto de temor, en el centro,<br />

en el final, de nuestra vida. Rápidamente, después,<br />

lo peor había pasado, pude consolarlo,<br />

sosteniendo su corazón en su sitio, desde atrás,<br />

y acariciándolo por <strong>del</strong>ante, su propia vida<br />

continuaba, y lo que lo había<br />

unido, alrededor <strong>del</strong> corazón – unido a él<br />

conmigo– ahora descansaba en nosotros, a nuestro alrededor,<br />

agua de mar, óxido, luz, fragmentos,<br />

los pequeños espirales eternos de eros<br />

aplanados a la fuerza.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

17

los curanderos<br />

/Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo, 2012.<br />

Cuando dicen, ¿Hay un médico a bordo?,<br />

que por favor se identifique, me acuerdo cuando mi<br />

entonces marido se levantaba, y yo me convertía en<br />

aquella que estaba a su lado. Ahora dicen<br />

que la cosa no funciona sin igualdad.<br />

Y después de esos primeros treinta años, yo no fui más<br />

la que él quería tener a su lado<br />

al pararse o al volver a su asiento<br />

– no yo sino ella, que también se levantará,<br />

cuando sea necesario. Ahora me los imagino,<br />

levantándose, juntos, con sus amplias<br />

alas de médicos, pájaros zancudos, – como cigüeñas con sus<br />

maletines de tal–para–cual<br />

balanceándose en sus picos. Y bueno. Fue como<br />

tuvo que ser, él no se ponía contento cuando se necesitaban<br />

las palabras, y yo me ponía de pie.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

18

gazal 1 <strong>del</strong> moretón<br />

/Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo, 2012.<br />

Ahora en mi cadera un óvalo negro-y-azul se ha vuelto azulvioleta<br />

como tinta en la cáscara de un gran<br />

corte, doloroso como mordida de amor, demasiado<br />

grande como para venir de una boca humana. Me gusta, mi<br />

adorno en la piel – marco de oro, color de la envidia<br />

adentro un camafeo, con tintes violeta<br />

sobre él, el picaporte que mordió deja un púrpura<br />

oscuro con movimientos como las temerosas patas<br />

de un ciempiés. Cuento los días que pasaron, y los que faltan<br />

para que se vayan los colores podridos y después<br />

de a poco desaparezcan. Algunas personas piensan que ya<br />

debiera haber superado a mi ex – quizá<br />

incluso yo misma pensé que lo superaría un poco más<br />

para estos días. Quizá superé a medias a quien él<br />

era, pero no a quien yo pensaba que era, y no superé<br />

la herida, repentino golpe mortal<br />

que parece venir de ningún sitio, pero que vino <strong>del</strong> núcleo<br />

de nuestra vida compartida. Dormí ahora, Sharon,<br />

dormí. Incluso mientras hablamos, el trabajo se está<br />

haciendo, por dentro. Naciste para sanar.<br />

Dormí y soñá – pero no con su regreso.<br />

Ya que no lo lastima, herilo, en tu sueño.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

1<br />

El ghazal, gazal, es un<br />

género lírico (forma poética)<br />

que consiste en coplas y<br />

estribillos, con cada línea<br />

compartiendo el mismo<br />

medidor. Es propio de las<br />

literaturas árabe, persa, turca<br />

y urdú. En la literatura árabe<br />

se trata de un poema cuya<br />

etimología está emparentada<br />

con las ideas de piropo,<br />

cumplido, etc.<br />

19

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

ser la que fue dejada<br />

/Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo, 2012.<br />

Si paso <strong>del</strong>ante de un espejo, me doy vuelta<br />

no quiero mirar,<br />

y ella no quiere que la vean. A veces<br />

no sé cómo hacer para seguir con esto.<br />

En general, cuando me siento así,<br />

al poco tiempo ya estoy llorando, acordándome<br />

de su cuerpo, o de una zona de su cuerpo,<br />

en general la parte de atrás, una parte de él<br />

que recuerde, ahora mismo, <strong>del</strong>iciosa, sin tanto<br />

detalle, y se aparece su espalda.<br />

Después de las lágrimas, el pecho duele menos,<br />

como si, dentro nuestro, una diosa de lo humano<br />

nos acariciara como un manantial de ternura.<br />

Me imagino que es así como la gente sigue a<strong>del</strong>ante, sin<br />

saber cómo. Me da tanta vergüenza<br />

<strong>del</strong>ante de mis amigos – ser la que fue dejada<br />

por aquel que supuestamente me conocía mejor,<br />

cada hora es un rincón de vergüenza, y yo estoy<br />

nadando, nadando, sosteniendo mi cabeza erguida,<br />

sonriendo, haciendo chistes, avergonzada, avergonzada,<br />

como estar desnuda con la ropa puesta, o como ser<br />

una niña, la obligación de portarse bien<br />

mientras odiás las circunstancias de tu vida. Adentro mío ahora<br />

hay un ser de puro odio, un ángel<br />

<strong>del</strong> odio. En la cancha de bádminton, ella lanza<br />

su tiro ganador, puro como una flecha,<br />

mientras por los ojales de mi blusa las chinches<br />

pican una carne que ya no parece<br />

importarle a nadie. En el espejo, mi torso<br />

parezco una sex–symbol mártir, llena de picaduras,<br />

o una jarra de crema con hojas de ortigas y flores <strong>del</strong> desierto,<br />

llena de leche de la bondad y la maldad<br />

humanas, y nadie está haciendo la fila para tomarla.<br />

¡Pero miren! ¡Estoy empezando a resignarme!<br />

Creo que ya no va a volver. Algo<br />

muere, adentro mío, cuando pienso en esto,<br />

como la muerte de una bruja en la cama<br />

mientras nace un bebé en la cama de al lado. Ten fe,<br />

viejo corazón. Qué es vivir, de todas formas,<br />

sino morir.<br />

20

una cosa<br />

secreta<br />

[2008]

todo<br />

/Una cosa Secreta, 2008.<br />

La mayoría de nosotros nunca somos concebidos.<br />

Muchos de nosotros nunca nacemos–<br />

vivimos en un océano íntimo por horas,<br />

semanas, con nuestras extremidades pérdidas o de más,<br />

o sosteniendo nuestra pobre segunda cabeza,<br />

creciendo en nuestro pecho, en nuestros brazos. Y muchos de nosotros,<br />

frutos <strong>del</strong> mar en su tallo, soñándonos alga<br />

o molusco, somos sacrificados en nuestros primeros meses.<br />

Y algunos que nacen viven sólo unos minutos,<br />

otros dos, o tres, veranos,<br />

o cuatro, y cuando se marchan, todo<br />

se marcha –la tierra, el firmamento–<br />

y el amor permanece, cuando nada existe, y busca.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

23

diagnóstico<br />

/Una cosa Secreta, 2008.<br />

Cuando tenía seis meses, ella supo que algo<br />

no andaba bien en mí. Yo hacía muecas<br />

que ella no había visto en ningún otro chico<br />

de la familia, nadie en toda la familia<br />

o en el barrio. Mi madre me dejó<br />

en las manos amables <strong>del</strong> pediatra, un doctor<br />

de nombre parecido a una marca de neumáticos:<br />

Hub Long. Mamá no le dijo<br />

lo que pensaba de verdad, que yo estaba Poseída.<br />

Eran nada más esas muecas extrañas –<br />

El doctor me agarró, y charló conmigo,<br />

habló como se habla con un bebé, y mi madre<br />

dijo, ¡Ahí lo está haciendo! ¡Mire!<br />

¡Ahí lo está haciendo! y el doctor dijo,<br />

Lo que su hija tiene<br />

se llama sentido<br />

<strong>del</strong> humor. Ahhh, contestó ella, y me llevó<br />

de regreso a la casa donde mi sentido sería testeado<br />

y considerado incurable.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

24

cuarto<br />

el<br />

sin<br />

barrer<br />

[2002]

domingo en<br />

el nido vacío<br />

/El cuarto sin Barrer, 2002.<br />

De a poco me sorprende esta tranquilidad.<br />

Nuestra casa desierta. No hay nadie,<br />

nadie necesita nada de nosotros,<br />

nadie va a necesitar nada de nosotros<br />

por meses. Nadie va a entrar a la habitación<br />

a pedir algo. Me siento como alguien<br />

abandonado — que llevaron a algún lugar, y lo dejaron,<br />

como en una especie de complejo turístico,<br />

no tenemos nada que hacer<br />

por nadie, todo es fácil.<br />

Quizá estamos muertos, quizá esto<br />

sea el cielo. Después <strong>del</strong> momento de la cama <strong>del</strong> amor, y después<br />

dormir un poco, nos despertamos a medias<br />

y yo miro, adentro de tus ojos, o adentro<br />

<strong>del</strong> íntimo blanco de un ojo<br />

mientras las preciosas pestañas dan su<br />

feliz espasmo de amplio horizonte, encuentro que puedo volverme<br />

inhumana mirando eso — el sencillo casisimultáneo<br />

abrir y cerrar — me<br />

olvido la palabra para los ojos y el concepto de los ojos, solo<br />

miro, un animal mirando el<br />

líquido dentro de la cabeza de otro,<br />

o a través de una mirilla afilada<br />

el diorama de otra dimensión,<br />

nube, cielo, agua pelágica, el<br />

mar <strong>del</strong> Edén, miro profundo<br />

sin conocimiento ni utilidad.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

27

sangre,<br />

lata,<br />

heno<br />

[1999]

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

cuando te viene<br />

/Sangre, lata, heno, 1999.<br />

Incluso cuando no tenés miedo de estar embarazada,<br />

es hermoso cuando te viene, encantadoramente sexual,<br />

a lo largo de ese cuello radiante<br />

y de los labios, su primer pliegue,<br />

y a veces, en los últimos pasos por el baño,<br />

dejás una estela deslumbrante, los pétalos<br />

que la niña de las flores esparce detrás de la novia. Y después sus colores,<br />

a veces un rojo casi dorado,<br />

o un bermellón oscuro, la gota que salta<br />

y se abre lentamente en el agua,<br />

una galaxia de jalea,<br />

el violeta–oscuro, el agua ondulante, apacible<br />

como un lago en la luna, nada de esto<br />

hiere, incluso la pequeña mancha<br />

en las medias negras con brillo carmesí<br />

oscilando en la <strong>del</strong>gada cuerda floja<br />

hacia la izquierda y la derecha en esa luminosa pista,<br />

inocente tapa de inodoro,<br />

la mancha no puede morir. Va a haber un huevo ahí,<br />

en algún lugar, en cualquier minuto, alado con montones<br />

de banderas asimétricas de plasma, una célula que<br />

de cerca es un planeta inmenso, de puntos y acuoso<br />

pero que no es nadie todavía. A veces,<br />

cuando miro este show <strong>del</strong>icado,<br />

es como si viese nevar, o estrellas fugaces,<br />

y pienso en los hombres, qué les parecerá a ellos<br />

cuando vemos la sangre caer lentamente de nuestro sexo,<br />

como si la tierra suspirara, leve<br />

y nosotras pudiésemos sentirla, y verla,<br />

como si la vida gimiera un poco, asombrada,<br />

y nosotras mismas fuéramos esa vida.<br />

31

la niñera<br />

/Sangre, lata, heno, 1999.<br />

El bebé tenía alrededor de seis meses,<br />

una nena. De esa edad, no había<br />

tocado a ninguna. Esa noche, cuando salieron<br />

la tomé en mis brazos y<br />

puse su boca sobre mi remera de algodón.<br />

No sabía realmente qué era una persona, yo<br />

quería que alguien me chupara el pezón,<br />

terminé encerrada en el baño,<br />

desnuda hasta la cintura, sosteniendo a la bebé,<br />

y lo único que ella quería eran mis anteojos, la sostuve<br />

suavemente, esperando que tomara la decisión,<br />

como un angelito, con su enfermera. Y ella no quería, sólo quería<br />

mis anteojos. Chupá, carajo, pensé,<br />

quería sentir el tirón de otra<br />

vida, quería sentirme necesaria, agarró mis anteojos<br />

y sonrió. Me puse de nuevo el corpiño<br />

y la remera, y la arropé, y le canté<br />

por última vez – claramente era<br />

la semana para buscar otro tipo de trabajo–<br />

y apagué la luz. De nuevo en el baño,<br />

a oscuras, me acosté en el piso, desnudé<br />

mi pecho contra los azulejos helados,<br />

deslicé la mano entre mis piernas y<br />

cabalgué, fuerte, sobre el suelo incendiado como una caldera, mis<br />

pezones sosteniéndome por encima de los azulejos<br />

como si estuviera volando,<br />

al revés, justo bajo el techo <strong>del</strong> mundo.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

32

una vez<br />

/Sangre, lata, heno, 1999.<br />

Vi a mi padre desnudo, una vez, abrí<br />

la puerta azul <strong>del</strong> baño,<br />

que él siempre trababa –si se abría, no había nada–<br />

y ahí, rodeado de brillantes cerámicas<br />

turquesas, sentado en el inodoro, estaba mi padre,<br />

todo él, y todo él<br />

era piel. En un instante, mi mirada lo recorrió<br />

de un único, súbito, limpio<br />

tirón, hacia arriba: dedos <strong>del</strong> pie, tobillo,<br />

rodilla, cadera, costilla, cuello,<br />

hombro, codo, muñeca, dedos<br />

mi padre. Se veía tan desprotegido,<br />

sin costuras, y tímido, como una nena en el inodoro,<br />

y si bien yo sabía que estaba sentado ahí<br />

para cagar, no había vergüenza,<br />

había una paz humana. Él me miró,<br />

yo dije Perdón, retrocedí, cerré la puerta<br />

pero lo había visto, mi padre un cordero esquilado,<br />

mi padre una nube en el cielo azul<br />

<strong>del</strong> baño azul, mi ojo había subido<br />

por la montaña, la ruta sinuosa <strong>del</strong><br />

hombre desnudo, había doblado la esquina,<br />

y descubierto su costado frágil – tierna<br />

barriga, borde de la cuna pélvica.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

33

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

estos días<br />

/Sangre, lata, heno, 1999.<br />

Cada vez que veo pechos grandes<br />

en una mujer pequeña, estos días, mi boca<br />

se abre, levemente.<br />

Si viene caminando por la calle, de frente hacia mí,<br />

es un poco doloroso dejarla pasar,<br />

una vez, me escuché, muy despacio,<br />

gimiendo. Y en el tren, esa vez–<br />

ella no tendría más de veinte,<br />

alta y esbelta– el movimiento <strong>del</strong> tren<br />

sacudía sus mamas, constante,<br />

como cacerolas llenas de agua, las miré<br />

chapotear, dentro de la piel apretada, y sentí<br />

una gran tristeza. Estoy tan<br />

cansada y sedienta. Quiero chupar<br />

calor dulce, lácteo, la sabrosa<br />

seda de la mujer humana a lo largo de<br />

mi mejilla. Quiero ser un bebé,<br />

quiero ser pequeña y estar desnuda, o con<br />

un pañal seco, entre brazos tiernos<br />

con el pezón en mi boca – trabajarlo, con suavidad,<br />

laxo y generoso en mis encías –<br />

no necesito dientes, ni siquiera las estrellas<br />

diurnas de los dientes en potencia, quiero<br />

ser de huesos blandos, flexible,<br />

una criatura que salió <strong>del</strong> útero<br />

quizá no hace pocos días<br />

sí un par de semanas, quiero ser un bebé poderoso,<br />

consciente de la dicha, de la nutrición<br />

brotando <strong>del</strong> pecho como la música<br />

de las esferas. Y no quiero<br />

que sea<br />

mi madre. Quiero empezar de nuevo.<br />

34

la<br />

fuente<br />

[1997]

primeras<br />

imágenes <strong>del</strong> cielo<br />

/La fuente, 1997.<br />

Me encantaba que las formas de los penes,<br />

sus tamaños, sus ángulos, todo en ellos<br />

fuera tal y como yo lo hubiera diseñado<br />

si los hubiera inventado. La piel, el modo en que la piel<br />

se endurece y se ablanda, su flexibilidad<br />

el modo en que la cabeza apenas cabe en la garganta,<br />

su punta casi tocando la válvula <strong>del</strong> estómago—<br />

y el pelo, que se extiende, o se arruga, <strong>del</strong>icado<br />

y libre—no pude superar todo esto,<br />

esta pasión tan intensa en mí<br />

como si hubiera sido hecho a mi voluntad, o mi<br />

deseo hecho a su voluntad—como si lo hubiera<br />

conocido antes de nacer, como si<br />

me recordara a mi misma viniendo<br />

a través de él, como Dios<br />

Padre todo a mi alrededor.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

37

me encanta cuando<br />

/La fuente, 1997.<br />

Me encanta cuando te das vuelta<br />

y te ponés encima mío de noche, tu peso<br />

continuo sobre mí como toneladas de agua, mis<br />

pulmones como una pequeña caja cerrada,<br />

la superficie firme de tus piernas con pelos<br />

abriendo mis piernas, mi corazón crece<br />

hasta convertirse en un guante de box<br />

tenso y violeta y después<br />

a veces me encanta quedarme ahí haciendo<br />

nada, mis poderosos brazos vencidos,<br />

sábanas de seda flotando desde la orilla,<br />

tu hueso púbico una pirámide<br />

punto de apoyo de otro punto<br />

–– radiante piedra angular. Después, en la quietud,<br />

me encanta sentirte crecer y crecer entre<br />

mis piernas como una planta en cámara rápida<br />

de la misma forma en que, en el auditorio, a<br />

oscuras, cerca <strong>del</strong> principio de nuestras vidas,<br />

encima de nosotros, los enormes tallos y las flores<br />

se abrían en silencio.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

38

plegaria de<br />

aquella época<br />

/La fuente, 1997.<br />

A veces me sorprendía a mí misma<br />

arrodillada bajo el marco de la puerta,<br />

una mujer sin fe, rezando:<br />

Por favor no dejes que nada le pase.<br />

No te lleves sus pensamientos,<br />

no trepes hasta su pequeño<br />

cerebro, que alucina en la cuerda floja, y lo empujes.<br />

No dejes que babee sobre sus cereales. Pero<br />

si esa es la única forma en que podemos tenerlo<br />

por favor déjanos tenerlo–<br />

incluso si lo único que podemos ver en su cara<br />

son las avenidas, vacías y amplias—<br />

y ponle de nuevo un babero,<br />

y dale cucharadas de azúcar negro, y maíz molido,<br />

y siéntate a su lado por el resto de los días,<br />

deseando que él se quede acá a pesar de que tal vez<br />

esté en el infierno. ¡Pero vivo! Pero vivo en el infierno.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

39

el<br />

padre<br />

[1992]

su quietud<br />

/El padre, 1992.<br />

El doctor le dijo a mi padre, “Usted me pidió<br />

que le diga cuando ya no se pueda hacer más nada.<br />

Se lo digo ahora.” Mi padre<br />

estaba sentado, bastante tranquilo, como siempre,<br />

con ese gesto suyo de no mover los ojos. Yo había imaginado<br />

que iba a volverse loco cuando entendiera que iba a morirse,<br />

que agitaría los brazos y gritaría. Se enderezó,<br />

flaco, y limpio, en su bata limpia,<br />

como un santo. El doctor dijo,<br />

“Podemos hacer algunas cosas que tal vez le den más tiempo,<br />

pero no podemos curarlo.” Mi padre dijo,<br />

“Gracias”. Y se quedó sentado, inmóvil, solo,<br />

con la dignidad de un estadista.<br />

Me senté a su lado. Ese era mi padre.<br />

Siempre supo que era mortal. Y yo había temido que tuvieran<br />

que atarlo. No me acordaba<br />

que siempre había permanecido<br />

quieto y silencioso para soportar las cosas,<br />

el licor una forma de quedarse quieto. No lo había<br />

conocido realmente. Mi padre tenía dignidad.<br />

Al final de su vida, su vida comenzó<br />

a despertar en mí.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

43

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

la mirada<br />

/El padre, 1992.<br />

Cuando mi padre empezó a atragantarse de nuevo<br />

gritó ¡Masaje en la espalda! en tono monocorde,<br />

como haciendo un anuncio,<br />

este hombre que nunca me había pedido nada.<br />

Estaba muy débil para inclinarse hacia a<strong>del</strong>ante,<br />

entonces deslicé mi mano entre su espalda<br />

caliente y la sábana caliente y él se quedó ahí<br />

con sus ojos abombados, esos ojos<br />

de borratinta usado que nunca me habían<br />

mirado realmente. Me sorprendió su piel<br />

<strong>del</strong>icada como un seno, voluptuosa<br />

como la piel de un bebé, pero seca, y mi mano<br />

también estaba seca, entonces froté sin esfuerzo, en círculos,<br />

él se quedó mirando fijo y ya no se ahogaba, yo cerré<br />

los ojos y lo froté, como si su cuerpo fuera su alma.<br />

Pude sentir su columna vertebral bien adentro, lo pude<br />

sentir dominado por el ahogo,<br />

toda mi vida había presentido que él estaba dominado por algo.<br />

Se hizo gárgaras, preparé el vaso,<br />

no detuve el masaje, él escupió,<br />

lo felicité, dejé que el inmenso placer<br />

de acariciar a mi padre despertara en mi cuerpo,<br />

y entonces pude tocarlo desde lo hondo de mi corazón,<br />

él cambió de posición, se recostó, sus ojos<br />

saltaron y se oscurecieron, la flema subió,<br />

yo acerqué el vaso hacia sus labios y dejó salir<br />

la cosa y se sentó de nuevo, cierto rubor volvió<br />

a su piel, y levantó su cabeza con timidez pero<br />

sin resistencia y me miró<br />

directamente, sólo por un momento, con una cara<br />

oscura y oscuros ojos brillantes y confiados.<br />

44

de<br />

celda<br />

la<br />

oro<br />

[1987]

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

solsticio de verano,<br />

ciudad de new york<br />

/La celda de Oro, 1987.<br />

Al final <strong>del</strong> día más largo <strong>del</strong> verano ya no pudo soportar más,<br />

subió por las escaleras de hierro hasta el techo <strong>del</strong> edificio,<br />

y caminó por la blanda superficie de alquitrán, hasta llegar al borde,<br />

puso una pierna sobre el complejo estaño verde de la cornisa<br />

y les dijo que si se acercaban un paso más, se terminaba todo.<br />

Entonces la enorme maquinaria <strong>del</strong> mundo empezó a funcionar para salvar su vida,<br />

los policías llegaron con sus uniformes azules grisáceos como el cielo de una tarde<br />

nublada,<br />

y uno se puso un chaleco antibalas, un<br />

caparazón negro alrededor de su propia vida,<br />

la vida <strong>del</strong> padre de sus hijos, por si<br />

el hombre estaba armado, y otro, colgado de una<br />

soga como un signo de su deber,<br />

apareció por un agujero en lo alto <strong>del</strong> edificio vecino<br />

como la brillante aureola que, dicen, está en lo alto de nuestras cabezas<br />

y empezó a acercarse con cuidado hacia el hombre que quería morir.<br />

El policía más alto se acercó hacia él sin rodeos,<br />

suave, lentamente, hablándole, hablando, hablando,<br />

mientras la pierna <strong>del</strong> hombre colgaba al borde <strong>del</strong> otro mundo<br />

y la multitud se juntaba en la calle, silenciosa, y la<br />

inquietante red con su entramado implacable fue<br />

desplegada cerca de la vereda y extendida y<br />

estirada como una sábana que se prepara para recibir a un recién nacido.<br />

Después todos se acercaron un poco más<br />

donde él se acurrucaba al lado de su muerte, su remera<br />

resplandecía un brillo lácteo como algo<br />

que crece en un plato, de noche, en un laboratorio y de pronto<br />

todo se detuvo<br />

mientras su cuerpo se sacudía y él<br />

bajaba <strong>del</strong> parapeto e iba hacia ellos<br />

y ellos se acercaban a él, pensé que le iban a dar<br />

una paliza, como una madre que ha perdido<br />

a su hijo y le grita cuando lo encuentra, ellos<br />

lo tomaron de los brazos y lo sostuvieron y<br />

lo apoyaron contra la pared de la chimenea y el<br />

policía alto encendió un cigarrillo<br />

en su propia boca, y se lo dio a él, y<br />

después todos encendieron sus cigarrillos, y<br />

las colillas rojas, radiantes ardieron como<br />

las pequeñas fogatas que encendíamos de noche<br />

en el principio de los tiempos.<br />

47

y los<br />

muertos<br />

los<br />

vivos<br />

[1983]

muerte de<br />

marilyn monroe<br />

/Los muertos y los vivos, 1983.<br />

Los hombres de la ambulancia tocaron su frío<br />

cuerpo, lo subieron, pesado como el hierro,<br />

a la camilla, trataron de cerrar<br />

su boca, cerraron sus ojos, ataron sus<br />

brazos a los costados, corrieron un mechón<br />

de pelo atrapado, como si importara,<br />

vieron la forma de sus pechos, aplanados por<br />

la gravedad, debajo de la sábana,<br />

la llevaron, como si fuera ella misma,<br />

bajando las escaleras.<br />

Estos hombres nunca fueron los mismos. Salieron<br />

después, como siempre,<br />

por uno o dos tragos, pero no pudieron mirarse<br />

a los ojos.<br />

Sus vidas dieron<br />

un vuelco – uno tuvo pesadillas, extraños<br />

dolores, impotencia, depresión. A otro ya no le gustaba<br />

su trabajo, su mujer parecía<br />

distinta, sus hijos. Incluso la muerte<br />

le pareció distinta –un lugar donde ella<br />

lo estaría esperando,<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

y otro se encontró parado de noche<br />

en el umbral de la habitación <strong>del</strong> sueño, escuchando a<br />

una mujer respirar, tan solo una mujer<br />

común<br />

respirando.<br />

51

la ausente<br />

/Los muertos y los vivos, 1983.<br />

(Para Muriel Rukeyser)<br />

La gente te sigue viendo y me cuenta<br />

lo blanca que estás, lo flaca que estás.<br />

Hace un año no te veo, pero lentamente estás<br />

apareciendo sobre mi cabeza, blanca como<br />

pétalos, blanca como leche, los oscuros<br />

angostos tallos de tus tobillos y tus muñecas,<br />

hasta que estás siempre conmigo, una floreciente<br />

rama suspendida sobre mi vida.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

52

para mi hija<br />

/Los muertos y los vivos, 1983.<br />

Esa noche va a llegar. En algún lugar alguien va a<br />

penetrarte, su cuerpo cabalgando<br />

bajo tu cuerpo blanco, separando<br />

tu sangre de tu piel, tus oscuros, líquidos<br />

ojos abiertos o cerrados, el sedoso<br />

aterciopelado pelo de tu cabeza fino<br />

como el agua derramada de noche, los <strong>del</strong>icados<br />

hilos entre tus piernas rizados<br />

como puntadas desprolijas. El centro de tu cuerpo<br />

se va a abrir, como una mujer que rompe la costura<br />

de su pollera para poder correr. Va a pasar,<br />

y cuando pase yo voy a estar exactamente acá<br />

en la cama con tu padre, así como cuando vos aprendiste a leer<br />

ibas y leías en tu habitación<br />

mientras yo leía en la mía, versiones de la misma historia<br />

que varían en la narración, la historia <strong>del</strong> río.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

53

satán<br />

dice<br />

[1980]

ese año<br />

/Satán dice, 1980.<br />

El año de la máscara de sangre, mi padre<br />

golpeando la puerta de vidrio para entrar<br />

fue el año en que encontraron<br />

el cuerpo de ella en las montañas<br />

en una tumba poco profunda, desnuda, blanca como<br />

un hongo, en estado de descomposición,<br />

violada, asesinada, la chica de mi clase.<br />

Ese fue el año en que mi madre nos llevó<br />

y nos escondió para que no estuviéramos ahí<br />

cuando le dijo que se fuera; para que no hubiera otro<br />

atarnos de las muñecas a la silla<br />

o negarnos la comida, no más<br />

forzarnos a comer, la cabeza sujetada hacia atrás,<br />

por la garganta en el restaurant,<br />

la vergüenza de la leche vomitada<br />

sobre el suéter con su vergüenza de pechos recientes<br />

Ese fue el año<br />

en que empecé a sangrar,<br />

cruzando ese límite por la noche<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

y en Historia, llegamos por fin<br />

a Auschwitz, en mi ignorancia<br />

sentí como si lo reconociera,<br />

la cara de mi padre como la cara de un guardia<br />

apartándose– o peor aún<br />

girando hacia mí.<br />

Las simétricas pilas de cuerpos blancos,<br />

la forma de pechos redondos<br />

y blancos de los montones<br />

el olor <strong>del</strong> humo, los perros las púas la<br />

soga el hambre. Esto le había sucedido a gente<br />

sólo algunos años atrás,<br />

en Alemania, los guardias eran protestantes<br />

como mi padre y yo, pero en mis sueños,<br />

cada noche, yo era una de aquellas<br />

a punto de ser asesinadas. Le había pasado a seis millones<br />

de judíos, a la familia de Jesús<br />

Yo no estaba entre ellos– y no todos<br />

habían muerto, y había una palabra<br />

que quería, en mi ignorancia,<br />

compartir con ellos, la palabra sobreviviente.<br />

57

es tarde<br />

/Satán dice, 1980.<br />

La bruma recorre el jardín<br />

como el humo de una batalla.<br />

Estoy tan cansada de las mujeres lavando los platos<br />

y de cuán inteligentes son los hombres, y de cómo quiero<br />

morder sus bocas y sentir sus pijas duras contra mí.<br />

La bruma se mueve, sobre los arbustos<br />

brillantes de hiedra venenosa y negros<br />

frutos como piedras. Estoy cansada de los hijos.<br />

Estoy cansada de lavar la ropa, quiero ser genial.<br />

La niebla se extiende en silencio sobre la maleza.<br />

Estamos sitiadas. La única forma de salir es a través<br />

<strong>del</strong> fuego, y yo no acepto ni un solo pelo más<br />

ninguna otra cabeza quemada.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

58

ahogándose<br />

/Satán dice, 1980.<br />

(Para Emily Davidson)<br />

Las madres están sentadas en la cocina, las últimas<br />

horas de la tarde, la luz como resina<br />

sólida en el agua junto a los tallos dorados,<br />

el té como ámbar de bailarinas; se sumergen<br />

en su lengua, charlan. Están siempre temiendo<br />

lo peor para sus hijos; la grieta entre las tablas,<br />

el clavo, el gancho, las escaleras al sótano,<br />

toda la sangre de sus pequeños cuerpos –<br />

Si mirás por la ventana mientras la oscuridad se filtra<br />

y el cuarto es como una jarra amarilla,<br />

hay un ángulo, hay un momento, en que se puede ver que cada<br />

madre<br />

lleva una mujer colgada al cuello<br />

arrastrándola– su propia madre que la agarra y la hunde<br />

en la luz que se apaga.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

59

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

satán dice<br />

/Satán dice, 1980.<br />

Estoy encerrada en una pequeña caja de cedro<br />

que tiene una imagen de pastores en el frente,<br />

y un tallado a ambos lados.<br />

La caja se sostiene sobre patas curvas.<br />

Tiene un cerrojo de oro, en forma de corazón<br />

y sin llave. Intento escribir para encontrar<br />

la salida de la caja cerrada<br />

que huele a cedro. Satán<br />

viene hasta mí, a la caja cerrada<br />

y dice, Voy a sacarte de acá. Decí<br />

mi padre es una mierda. Digo<br />

mi padre es una mierda y Satán<br />

se ríe y dice, Se está abriendo.<br />

Decí que tu madre es una puta.<br />

Mi madre es una puta. Algo<br />

se abre y se quiebra cuando lo digo.<br />

Mi espalda se endereza en la caja de cedro<br />

como la espalda rosa de la bailarina <strong>del</strong> prendedor<br />

con un ojo de rubí, que descansa a mi lado<br />

en el terciopelo de la caja de cedro.<br />

Decí mierda, decí muerte, decí a la mierda el padre,<br />

me dice Satán, al oído.<br />

El dolor <strong>del</strong> pasado encerrado zumba<br />

en la caja de la infancia en su escritorio, bajo<br />

el terrible ojo esférico <strong>del</strong> estanque<br />

con grabados de rosas a su alrededor, donde<br />

el odio a ella misma se contemplaba en su pena.<br />

Mierda. Muerte. A la mierda el padre.<br />

Algo se abre. Satán dice<br />

¿No te sentís mucho mejor?<br />

La luz parece quebrarse sobre el <strong>del</strong>icado<br />

prendedor e<strong>del</strong>weiss, tallado en dos<br />

tipos de madera. También lo amo,<br />

sabés, le digo a Satán desde lo oscuro<br />

de la caja cerrada. Los amo pero<br />

estoy tratando de contar lo que ocurrió<br />

en nuestro pasado perdido. Por supuesto, dice él<br />

y sonríe, por supuesto. Ahora decí: tortura.<br />

Veo, a través de la oscuridad impregnada de cedro,<br />

60

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

el borde de una gran bisagra que se abre.<br />

Decí: la pija <strong>del</strong> padre, la concha<br />

de la madre, dice Satán, Voy a sacarte.<br />

El ángulo de la bisagra se ensancha<br />

hasta que veo el contorno <strong>del</strong> tiempo<br />

antes de que yo existiera, cuando ellos estaban<br />

encerrados en la cama. Cuando digo<br />

las palabras mágicas, Pija, Concha,<br />

amablemente Satán dice, Salí.<br />

Pero el aire de afuera<br />

es pesado y denso como humo caliente.<br />

Vení, dice, y siento su voz<br />

respirando desde afuera.<br />

La salida es a través de la boca de Satán.<br />

Entrá en mi boca, dice, ya estás ahí,<br />

y la enorme bisagra<br />

empieza a cerrarse. Ah no, también<br />

los amaba, resguardo<br />

mi cuerpo tenso<br />

en la casa de cedro.<br />

Satán se esfuma por el ojo de la cerradura.<br />

Me quedo encerrada en la caja, él sella<br />

el cerrojo en forma de corazón con la cera de su lengua.<br />

Ahora es tu tumba, dice Satán.<br />

Apenas escucho;<br />

caliento mis manos<br />

frías en el ojo de rubí<br />

de la bailarina –el fuego,<br />

el súbito descubrimiento de lo que es el amor.<br />

61

en<br />

de<br />

Sharon Olds

stag’s<br />

leap<br />

[2012]

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

crazy<br />

/Stag’s Leap, 2012.<br />

I've said that he and I had been crazy<br />

for each other, but maybe my ex and I were not<br />

crazy for each other. Maybe we<br />

were sane for each other, as if our desire<br />

was almost not even personal—<br />

it was personal, but that hardly mattered, since there<br />

seemed to be no other woman<br />

or man in the world. Maybe it was<br />

an arranged marriage, air and water and<br />

earth had planned us for each other—and fire,<br />

a fire of pleasure like a violence<br />

of kindness. To enter those vaults together, like a<br />

solemn or laughing couple in formal<br />

step or writhing hair and cry, seemed to<br />

me like the earth's and moon's paths,<br />

inevitable, and even, in a way,<br />

shy—enclosed in a shyness together,<br />

equal in it. But maybe I<br />

was crazy about him—it is true that I saw<br />

that light around his head when I'd arrive second<br />

at a restaurant—oh for God's sake,<br />

I was besotted with him. Meanwhile the planets<br />

orbited each other, the morning and the evening<br />

came. And maybe what he had for me<br />

was unconditional, temporary<br />

affection and trust, without romance,<br />

though with fondness—with mortal fondness. There was no<br />

tragedy, for us, there was<br />

the slow–revealed comedy<br />

of ideal and error. What precision of action<br />

it had taken, for the bodies to hurtle through<br />

the sky for so long without harming each other.<br />

67

the easel<br />

/Stag’s Leap, 2012.<br />

When I build a fire, I feel purposeful––<br />

proud I can unscrew the wing nuts<br />

from off the rusted bolts, dis–<br />

assembling one of the things my ex<br />

left when he left right left. And laying its<br />

narrow, polished, maple angles<br />

across the kindling, providing for updraft––<br />

good. Then by flame–light I see: I am burning<br />

his old easel. How can that be,<br />

after the hours and hours–all told, maybe<br />

weeks, a month of stillness–mo<strong>del</strong>ling<br />

for him, our first years together,<br />

odour of acrylic, stretch of treated<br />

canvas. I am burning his left–behind craft,<br />

he who was the first to turn<br />

our family, naked, into art.<br />

What if someone had told me, thirty<br />

years ago: If you give up, now,<br />

wanting to be an artist, he might<br />

love you all your life–what would I<br />

have said? I didn’t even have an art,<br />

it would come from out of our family’s life–<br />

what could I have said: nothing will stop me.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

68

the worst thing<br />

/Stag’s Leap, 2012.<br />

One side of the highway, the waterless hills.<br />

The other, in the distance, the tidal wastes,<br />

estuaries, bay, throat<br />

of the ocean. I had not put it into<br />

words, yet—the worst thing,<br />

but I thought that I could say it, if I said it<br />

word by word. My friend was driving,<br />

sea–level, coastal hills, valley,<br />

foothills, mountains—the slope, for both,<br />

of our earliest years. I had been saying<br />

that it hardly mattered to me now, the pain,<br />

what I minded was—say there was<br />

a god—of love—and I’d given—I had meant<br />

to give—my life—to it—and I<br />

had failed, well I could just suffer for that—<br />

but what, if I,<br />

had harmed, love? I howled this out,<br />

and on my glasses the salt water pooled, almost<br />

sweet to me, then, because it was named,<br />

the worst thing—and once it was named,<br />

I knew there was no god, there were only<br />

people. And my friend reached over,<br />

to where my fists clutched each other,<br />

and the back of his hand rubbed them, a second,<br />

with clumsiness, with the courtesy<br />

of no eros, the homemade kindness.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

69

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

unspeakable<br />

/Stag’s Leap, 2012.<br />

Now I come to look at love<br />

in a new way, now that I know I’m not<br />

standing in its light. I want to ask my<br />

almost-no-longer husband what it’s like to not<br />

love, but he does not want to talk about it,<br />

he wants a stillness at the end of it.<br />

And sometimes I feel as if, already,<br />

I am not here – to stand in his thirty-year<br />

sight, and not in love’s sight,<br />

I feel an invisibility<br />

like a neutron in a cloud chamber buried in a mile-long<br />

accelerator, where what cannot<br />

be seen is inferred by what the visible<br />

does. After the alarm goes off,<br />

I stroke him, my hand feels like a singer<br />

who sings along with him, as if it is<br />

his flesh that’s singing, in its full range,<br />

tenor of the higher vertebrae,<br />

baritone, bass, contrabass.<br />

I want to say to him, now, What<br />

was it like, to love me – when you looked at me,<br />

what did you see? When he loved me, I looked<br />

out at the world as if from inside<br />

a profound dwelling, like a burrow, or a well, I’d gaze<br />

up, at noon, and see Orion<br />

shining – when I thought he loved me, when I thought<br />

we were joined not just for breath’s time,<br />

but for the long continuance,<br />

the hard candies of femur and stone,<br />

the fastnesses. He shows no anger,<br />

I show no anger but in flashes of humour,<br />

all is courtesy and horror. And after<br />

the first minute, when I say, Is this about<br />

her, and he says, No, it’s about<br />

you, we do not speak of her.<br />

70

the last hour<br />

/Stag’s Leap, 2012.<br />

Suddenly, the last hour<br />

before he took me to the airport, he stood up,<br />

bumping the table, and took a step<br />

toward me, and like a figure in an early<br />

science fiction movie he leaned<br />

forward and down, and opened an arm,<br />

knocking my breast, and he tried to take some<br />

hold of me, I stood and we stumbled,<br />

and then we stood, around our core, his<br />

hoarse cry of awe, at the centre,<br />

at the end of, of our life. Quickly, then,<br />

the worst was over, I could comfort him,<br />

holding his heart in place from the back<br />

and smoothing it from the front, his own<br />

life continuing, and what had<br />

bound him, around his heart – and bound him<br />

to me – now lying on and around us,<br />

sea–water, rust, light , shards,<br />

the little eternal curls of eros<br />

beaten out straight.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

71

the healers<br />

/Stag’s Leap, 2012.<br />

When they say, If there are any doctors aboard,<br />

would they make themselves known, I remember when my then<br />

husband would rise, and I would get to be<br />

the one he rose from beside. They say now<br />

that it does not work, unless you are equal.<br />

And after those first thirty years,<br />

I was not the one he wanted to rise from<br />

or return to – not I but she who would also<br />

rise, when such were needed. Now I see them,<br />

lifting, side by side, on wide,<br />

medical, wading–bird wings – like storks with the<br />

doctor bags of like–loves–like<br />

dangling from their beaks. Oh well. It was the way<br />

it was, he did not feel happy when words<br />

were called for, and I stood.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

72

uise ghazal<br />

/Stag’s Leap, 2012.<br />

Now a black-and-blue oval on my hip has turned blueviolet<br />

as the ink-brand on the husk-fat of a prime<br />

cut, sore as a lovebite, but too<br />

large for a human mouth. I like it, my<br />

flesh brooch–gold rim, envy-color<br />

cameo within, and violet mottle<br />

on which the door-handle that bit is a black<br />

purple with wiggles like trembling decapede<br />

legs. I count back the days, and forward<br />

to when it will go its rot colors and then<br />

slowly fade. Some people think I should<br />

be over my ex by now–maybe<br />

I thought I might have been over him more<br />

by now. Maybe I’m half over who he<br />

was, but not who I thought he was, and not<br />

over the wound, sudden deathblow<br />

as if out of nowhere, though it came from the core<br />

of our life together. Sleep now, Sharon,<br />

sleep. Even as we speak, the work is being<br />

done, within. You were born to heal.<br />

Sleep and dream–but not of his return.<br />

Since it cannot harm him, wound him, in your dream.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

73

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

known to be left<br />

/Stag’s Leap, 2012.<br />

If I pass a mirror, I turn away,<br />

I do not want to look at her,<br />

and she does not want to be seen. Sometimes<br />

I don’t see how I’m going to go on doing this.<br />

Often, when I feel that way,<br />

within a few minutes I am crying, remembering<br />

his body, or an area of it,<br />

his backside often, a part of him<br />

just right now to think of, luscious, not too<br />

detailed, and his back turned to me.<br />

After tears, the heart is less sore,<br />

as if some goddess of humanness<br />

within us has caressed us with a gush of tenderness.<br />

I guess that’s how people go on, without<br />

knowing how. I am so ashamed<br />

before my friends – to be known to be left<br />

by the one who supposedly knew me best,<br />

each hour is a room of shame, and I am<br />

swimming, swimming, holding my head up,<br />

smiling, joking, ashamed, ashamed,<br />

like being naked with the clothed, or being<br />

a child, having to try to behave<br />

while hating the terms of your life. In me now<br />

there’s a being of sheer hate, like an angel<br />

of hate. On the badminton lawn, she got<br />

her one shot, pure as an arrow,<br />

while through the eyelets of my blouse the no–see–ums<br />

bit the flesh no one seems now<br />

to care to touch. In the mirror, the torso<br />

looks like a pinup hives martyr,<br />

or a cream pitcher speckled with henbit and pussy-paws,<br />

full of the milk of human kindness<br />

and unkindness, and no one is lining up to drink.<br />

But look! I am starting to give him up!<br />

I believe he is not coming back. Something<br />

has died, inside me, believing that,<br />

like the death of a crone in one twin bed<br />

as a child is born in the other. Have faith,<br />

old heart. What is living, anyway,<br />

but dying.<br />

74

one secret<br />

thing<br />

[2008]

everything<br />

/One secret Thing, 2008.<br />

Most of us are never conceived.<br />

Many of us are never born–<br />

we live in a private ocean for hours,<br />

weeks, with our extra or missing limbs,<br />

or holding our poor second head,<br />

growing from our chest, in our arms. And many of us,<br />

sea–fruit on its stem, dreaming kelp<br />

and whelk, are culled in our early months.<br />

And some who are born live only for minutes,<br />

others for two, or for three, summers,<br />

or four, and when they go, everything<br />

goes –the earth, the firmament–<br />

and love stays, where nothing is, and seeks.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

77

diagnosis<br />

/One secret Thing, 2008.<br />

By the time I was six months, she knew something<br />

was wrong with me. I got looks on my face<br />

she had not seen on any child<br />

in the family, or the extended family,<br />

or the neighborhood. My mother took me in<br />

to the pediatrician with the kind hands,<br />

a doctor with a name like a suit size for a wheel:<br />

Hug Long. My mom did not tell him<br />

what she thought in truth, that I was Possessed.<br />

It was just these strange looks on my face –<br />

He held me, and conversed with me,<br />

chatting as one does with a baby, and my mother<br />

said, She´s doing it now! Look!<br />

She´s doing it now! and the doctor said,<br />

What you daughter has<br />

has called a sense<br />

of humor. Ohhh, she said, and took me<br />

back to the house where that sense would be tested<br />

and found to be incurable.<br />

Salto <strong>del</strong> Ciervo / Sharon Olds / Traducción de Natalia Leiderman y Patricio Foglia<br />

78

the<br />

unswept<br />

room<br />

[2002]

sunday in<br />

the empty nest<br />

/The unswept room, 2002.<br />

Slowly it strikes me how quiet it is.<br />

It’s deserted at our house. There’s no one here,<br />

no one needing anything of us,<br />

and no one will need anything of us<br />

for months. No one will walk into the bedroom<br />

and ask for something. I feel like someone<br />

abandoned-- taken somewhere, and left,<br />

some kind of resort, there’s nothing for us to do<br />

for anyone, everything is easy.<br />

Maybe we’re dead, maybe this<br />

is heaven. After the hour in love’s bed, and then<br />

sleeping a little, we half wake<br />

and I look, into your eyes, or into<br />

the inner white of one eye<br />

while the lovely lids do their wide-horizon<br />

basking jerk, I find I can go<br />

inhuman watching that—the single nearsimultaneous<br />

dip and rise—I forget<br />

the word for eyes and the concept of eyes, I just<br />

look , an animal looking into the<br />

liquid inside the other’s head,<br />

or through a tapered peephole into<br />

the diorama of another dimension,<br />

cloud, sky, pelagic water, the<br />