You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Le imponenti macchine a colonna dell’inizio secolo sono in stile Liberty, realizzate in fonderia, venivano arricchite con<br />

decorazioni cromate e scritte smaltate <strong>di</strong> pregevole fattura. Nella piccola officina <strong>di</strong> via Parini a Milano, la Pavoni fabbrica<br />

tre modelli: piccolo, me<strong>di</strong>o e grande. E ne vende al ritmo <strong>di</strong> una al giorno. La torinese Victoria Arduino perfeziona il sistema<br />

del caffè a vapore, ma le Officine Fratelli Romanut, la cui macchina a colonna in cima sfoggia il leone <strong>di</strong> San Marco<br />

cesellato a mano, sposano il funzionamento elettrico e a gas. Si va verso gli anni Venti, L’Augusta Massocco & C, la Snider,<br />

la Universal, “carrozzerie” cromate per eleganti macchine del caffè a funzionamento elettrico istantaneo. Arrivano gli anni<br />

Trenta, la Victoria Arduino fabbrica un modello la cui immagine nelle linee e nei volumi attinge agli stilemi fascisti. Giuseppe<br />

Cimbali, l’artigiano che fabbrica i componenti delle macchine, negli anni Trenta avvia la produzione in proprio, le Cimbali<br />

sono richiestissime. L’ingegner Simonelli, nel 1936, da Macerata mette sul mercato il suo modello a colonna con meccanica<br />

per preparazione istantanea. Nel secondo dopoguerra, Gaggia con la Classica 1948 sostituisce il modello “a colonna”<br />

con il funzionamento “a pistone”, e la bevanda che prima sapeva d’amaro e <strong>di</strong> bruciato <strong>di</strong>venta la moderna “crema caffè”.<br />

Le macchine Gaggia si <strong>di</strong>ffondono rapidamente nei bar e nei ristoranti del Belpaese. Dagli anni Cinquanta entrano in scena<br />

le scelte artistiche, la materia <strong>di</strong>venta linguaggio a firma <strong>di</strong> gran<strong>di</strong> designer e architetti. Si cimentano artisti come Gio Ponti, Luigi<br />

Caccia Dominioni, Bruno Munari, Alberto Rosselli, Antonio Fornaroli, Giuseppe De Gotzen, Marco Zanuso, Rodolfo Bonetto,<br />

i fratelli Castiglioni, Giovanni Travasa, Ettore Sottsass, Enzo Mari, Gianfranco Salvemini, Pininfarina, che hanno realizzato<br />

“strumenti” <strong>di</strong> lavoro <strong>di</strong>venuti dei veri e propri elementi <strong>di</strong> collezionismo che contribuiranno ad imporre l’inconfon<strong>di</strong>bile stile<br />

nazionale nel mondo. Degna <strong>di</strong> nota la Pavoni Modello Concorso del 1956. Il design <strong>di</strong> Enzo Mari e Bruno Munari le fa<br />

meritare il soprannome <strong>di</strong> Diamante. Ancora oggi tra le più ricercate dai ristoratori è la Faema - azienda che, più <strong>di</strong> tutte, ha<br />

saputo scrivere il futuro delle macchine da caffè - E61, del 1961. Decorata con una banda rossa su fondo bianco, veniva<br />

pubblicizzata come unica al mondo ad iniezione <strong>di</strong>retta, “dotata a richiesta <strong>di</strong> idonea apparecchiatura alimentata da una<br />

comune batteria”, così anche senza corrente elettrica il caffè è garantito. Ma nell’archivio del collezionista si possono<br />

trovare testimonianze e curiosità <strong>di</strong> ogni genere, come i cento anni del costo delle tazzine, la ricostruzione dei tempi tecnici<br />

del caffè - una volta ci volevano tre minuti, oggi quaranta secon<strong>di</strong> – oltre ad un cortometraggio ottenuto montando in<br />

successione scene tratte da film famosi che hanno per filo conduttore l’apparizione <strong>di</strong> una macchina del caffè espresso.<br />

I Sensi <strong>di</strong> <strong>Romagna</strong><br />

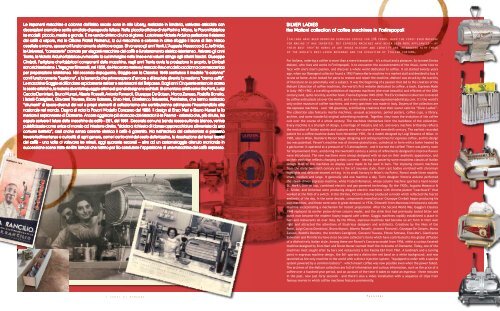

SILVER LADIES<br />

the Maltoni collection of coffee machines in Forlimpopoli<br />

Italians have been drinking espresso coffee for 108 years, when the first-ever machine<br />

for making it was invented. But espresso machines have never been mere appliances – at<br />

their best they’re works of art whose history and identity are interwoven with those<br />

of the world’s best-loved beverage and the evolution of Italian customs.<br />

For Italians, ordering a coffee is more than a mere transaction – it’s a ritual and a pleasure. So to meet Enrico<br />

Maltoni, who lives and works in Forlimpopoli, is to encounter the accoutrements of the ritual, come face to<br />

face with one’s man’s passion, and <strong>di</strong>scover a whole world de<strong>di</strong>cated to coffee. It all started twenty years<br />

ago, when our Romagnol collector found a 1952 Faema Marte machine in a market stall and decided to buy it<br />

to use at home. As he looked for parts to restore and repair the machine, Maltoni was struck by the scarcity<br />

of literature on so potentially vast a subject. It was the beginning of a passion that led to the creation of the<br />

Maltoni Collection of coffee machines, the world’s first website de<strong>di</strong>cated to coffee, a book, Espresso Made<br />

in Italy 1901-1962, a travelling exhibition of espresso machines (the most beautiful and efficient of the 20th<br />

century) and, quite recently, another book, Faema Espresso 1945-2010. The Enrico Maltoni collection is revered<br />

by coffee enthusiasts all over the world, and is now online at www.espressomadeinitaly.com. It’s the world’s<br />

only online museum of coffee machines, and every specimen was made in Italy. Doyens of the collection are<br />

the espresso machines – over 100 gleaming, scintillating creations that their owner calls his “Silver La<strong>di</strong>es”.<br />

The collection also features mocha machines, unusual accessories, period posters, coffee cups, a library,<br />

archive, and some wonderful original advertising material. Together, they trace the evolution of the coffee<br />

cult over the course of a whole century. The machines themselves form the backbone of the collection.<br />

Every machine is a triumph of design, a marriage of industry and art, and every machine brilliantly reflects<br />

the evolution of Italian society and customs over the course of the twentieth century. The earliest recorded<br />

patent for a coffee machine dates from November 1901, for a model designed by Luigi Bezzera of Milan. In<br />

1905, also in Milan, Desiderio Pavoni began designing and selling machines for espresso coffee, and his design<br />

too was patented. Pavoni’s machine was of chrome-plated brass, cylindrical in form with a boiler heated by<br />

a gas burner. It operated at a pressure of 1.5 atmospheres – and it burned the coffee! There was plenty room<br />

for improvement then, and during the twentieth century a series of refinements designed to improve flavour<br />

were introduced. The new machines were always designed with an eye on their aesthetic appearance, and<br />

so their evolution reflects changing artistic currents – leaving for posterity some matchless classics of Italian<br />

design. Most of the machines on <strong>di</strong>splay were made to be used in bars. The imposing column machines<br />

from the early twentieth century are in the art nouveau style, their cast bo<strong>di</strong>es enriched with chromium<br />

highlights and delicate enamel writing. In its small factory in Milan’s via Parini, Pavoni made three models:<br />

small, me<strong>di</strong>um and large. It generally sold one machine a day. Turin designer Victoria Arduino perfected<br />

the steam-driven espresso machine, while Fratelli Romanut, whose column machine sported a hand-tooled<br />

St. Mark’s Lion on top, combined electric and gas-powered technology. By the 1920s, Augusta Massocco &<br />

C, Snider, and Universal were producing elegant electric machines with chrome-plated “coachwork” that<br />

worked at the flick of a switch. In the thirties, Victoria Arduino produced a model which reflected the fascist<br />

aesthetic of the day. In the same decade, components manufacturer Giuseppe Cimbali began producing his<br />

own machines, and these were soon in great demand. In 1936, Simonelli from Macerata introduced a column<br />

machine incorporating a mechanism for instant preparation. After the Second World War, Gaggia’s Classica<br />

1948 replaced its earlier piston-driven column model, and the drink that had previously tasted bitter and<br />

burnt now became the modern foamy-topped café crème. Gaggia machines rapidly established a place in<br />

bars and restaurants all over Italy. By the fifties, espresso machines had become an art form in their own<br />

right and attracted the attentions of illustrious designers and architects. Creations by the likes of Gio<br />

Ponti, Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Bruno Munari, Alberto Rosselli, Antonio Fornaroli, Giuseppe De Gotzen, Marco<br />

Zanuso, Rodolfo Bonetto, the brothers Castiglioni, Giovanni Travasa, Ettore Sottsass, Enzo Mari, Gianfranco<br />

Salvemini and Pininfarina have since become collector’s items which have contributed to the global <strong>di</strong>ffusion<br />

of a <strong>di</strong>stinctively Italian style. Among these are Pavoni’s Concorso model from 1956, while a curious faceted<br />

machine designed by Enzo Mari and Bruno Munari earned itself the nickname of Diamante. Today, one of the<br />

machines most sought after by bars and restaurants is the Faema E61 from 1961. A landmark and a turning<br />

point in espresso machine design, the E61 sported a <strong>di</strong>stinctive red band on a white background, and was<br />

launched as the only machine in the world with a <strong>di</strong>rect injection system, “equipped to order with a special<br />

system powered by a common battery” – which meant coffee was now possible even when the power failed.<br />

The archives of the Maltoni collection are full of information and curious information, such as the price of a<br />

coffee over a hundred-year period, and an account of the time it takes to make an espresso – three minutes<br />

in the past, now just forty seconds – and there’s also a video installation with a sequence of clips from<br />

famous movies in which coffee machines feature prominently.<br />

[18 19]<br />

Si Si cambia cambia più più facilmente facilmente religione<br />

religione<br />

che caffè. Georges Courteline<br />

Passioni