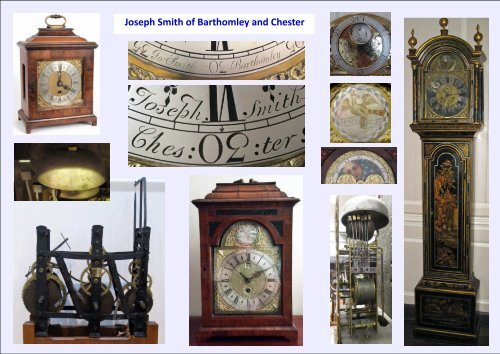

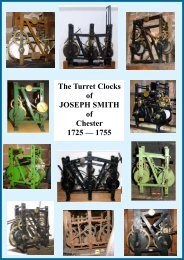

Joseph Smith Clockmaker of Barthomley and Chester

Joseph Smith of Barthomley and Chester was a prolific clockmaker in the eighteenth century. Take a look at some of his clocks and read his history.

Joseph Smith of Barthomley and Chester was a prolific clockmaker in the eighteenth century. Take a look at some of his clocks and read his history.

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Barthomley</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Chester</strong>

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Barthomley</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Chester</strong><br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> table clock made at <strong>Barthomley</strong><br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> was a son <strong>of</strong> the well known <strong>and</strong> highly regarded<br />

clockmaker Gabriel <strong>Smith</strong> (<strong>of</strong> <strong>Barthomley</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nantwich).<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> was born c. 1688 <strong>and</strong> learned his trade from his father. Having<br />

lived <strong>and</strong> worked in the village <strong>of</strong> <strong>Barthomley</strong> for many years, Gabriel<br />

<strong>Smith</strong> left around 1722 <strong>and</strong> relocated his business in the nearby market<br />

town <strong>of</strong> Nantwich. <strong>Joseph</strong> remained at the family home until 1725<br />

when he too left <strong>and</strong> settled in <strong>Chester</strong>.<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> chose the Gloverstone area where he could trade as a<br />

clockmaker without the requirement to be a freeman. Gloverstone was<br />

within the old city walls, but was not subject to the city Assembly’s<br />

jurisdiction. Hence it attracted many free-spirited artisans <strong>and</strong><br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals. <strong>Clockmaker</strong>s were especially attracted to the area. Soon<br />

after his arrival in the city, <strong>Joseph</strong> made a three train turret clock for<br />

the cathedral which he went on to wind <strong>and</strong> maintain until infirmity in<br />

old age prevented him doing so. His wife <strong>and</strong> sons then took over.

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Barthomley</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Chester</strong><br />

This thirty hour longcase clock, made by <strong>Joseph</strong><br />

<strong>Smith</strong> while still living <strong>and</strong> working at <strong>Barthomley</strong>,<br />

is one <strong>of</strong> very few <strong>of</strong> this duration made by this<br />

clockmaker.<br />

It is housed in a country style oak case which may<br />

be <strong>of</strong> earlier manufacture than the clock.<br />

The clock dial <strong>and</strong> mechanism are thought to have<br />

been made around 1720.

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> three train turret clock for <strong>Chester</strong> Cathedral<br />

<strong>Chester</strong> Cathedral Clock<br />

There was already a clock in the cathedral, which was wound<br />

<strong>and</strong> maintained by Charles Whitehead, smith <strong>and</strong> mason <strong>of</strong> the<br />

city. In September 1724, the cathedral accounts book lists<br />

£0 5s 0d spent ‘at Bargaining for a new Church clock’. This may<br />

well have been a meeting between <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> <strong>and</strong> the<br />

cathedral authorities, at which the clock was <strong>of</strong>fered as a<br />

‘master piece’. No records <strong>of</strong> any monies spent on acquiring the<br />

clock have yet been found, which could indicate that it was<br />

made as a gift. Towards the end <strong>of</strong> the following year James<br />

Comberbach, timber merchant, was paid £2 11s 0d ‘for timber<br />

for ye clock case’ <strong>and</strong> two months later Charles Whitehead<br />

received his final payment <strong>of</strong> £0 8s 0d for ‘tending ye old clock’.<br />

Even though religious communities relied on their clocks to<br />

timetable their lives <strong>and</strong> services, clocks were not highly<br />

valued. They are rarely mentioned in church histories, whereas<br />

bells are described in detail. The cathedral archives have been<br />

only partially indexed. The four account books contain the only<br />

known records relating to <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>’s clock that were<br />

written during his lifetime. All the available indexes have been<br />

searched for other references to the clock. It was customary for<br />

a clockmaker to commit to maintain a turret clock during his<br />

lifetime. This was certainly the case with the cathedral clock.<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> was paid annually, usually at Michaelmas, for<br />

maintenance <strong>of</strong> the clock. The annual salary for the job was<br />

£0 16s 0d <strong>and</strong> remained unchanged from 1727 until 1766.

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> three train turret clock for <strong>Chester</strong> Cathedral, continued<br />

The payment was increased occasionally if repairs were required, for example<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the bells was sent to London for re-casting during the 1730s; on 18 th<br />

December 1738-9, after the bell’s return this entry was put in the accounts<br />

book: ‘To Mr <strong>Smith</strong> for cleaning <strong>and</strong> regulating the clock after the Great Bell<br />

was put up - £0 9s 0d.’<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>’s connection with the cathedral was made even closer when he<br />

sent his boys to the King’s School. The school was founded by King Henry VIII<br />

in 1541 following the dissolution <strong>of</strong> St Werburgh's Abbey, which became<br />

<strong>Chester</strong> Cathedral. It was housed in the former monastic refectory for most<br />

<strong>of</strong> the next 400 years. It was to have twenty-four poor <strong>and</strong> friendless boys<br />

aged between nine <strong>and</strong> fifteen. The boys, usually termed King's Scholars,<br />

were elected by competitive examination <strong>and</strong> received a free education <strong>and</strong><br />

an allowance. The ‘poor <strong>and</strong> friendless’ requirement must have been less<br />

stringently enforced as the years passed. <strong>Joseph</strong>’s eldest son, John was first<br />

listed as a King’s Scholar in the account book in 1733, followed by Gabriel(2)<br />

in 1735, Thomas in 1737 <strong>and</strong> Samuel in 1742. It is not known how long the<br />

boys attended the school, but Samuel was still there in 1745.<br />

In October 1744 Thomas was paid the year’s salary for taking care <strong>of</strong> the<br />

clock <strong>and</strong> the following year, Mrs <strong>Smith</strong> collected her husb<strong>and</strong>’s salary.<br />

Payments to <strong>Joseph</strong> then continued until 1763, when Gabriel(2) was paid ‘his<br />

year’s salary’. After that time, <strong>Joseph</strong> was paid for three more years, the final<br />

payment to him being on 4 th April 1766. John <strong>Smith</strong> continued the<br />

maintenance <strong>of</strong> the clock until his last salary was paid on 9 th November 1781.<br />

The <strong>Smith</strong> clock continued in service until 1872/3 when it was replaced by a<br />

flatbed Westminster chiming clock made by JB Joyce & Co. <strong>of</strong> Whitchurch.<br />

Like its predecessor, the Joyce clock had no dial, but simply told the time by<br />

full quarter chiming <strong>and</strong> striking the hours. At the time <strong>of</strong> the clock’s<br />

installation, the 1867 carillon was re-sited. It lessened the job <strong>of</strong> the<br />

bellringers, by playing the first lead <strong>of</strong> Bob Triples. The Joyce clock <strong>and</strong><br />

carillon were themselves superseded by an electric chiming mechanism<br />

which was installed in the new Addleshaw Bell Tower when it was completed<br />

in 1975.

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> three train turret clock for <strong>Chester</strong> Cathedral, continued<br />

The <strong>Smith</strong> clock was auctioned by Christies in their sale <strong>of</strong> ’Important Clocks’<br />

on 7th December 2005.<br />

The catalogue stated:<br />

A GEORGE 1 IRON AND BRASS THREE TRAIN POSTED FRAME TURRET<br />

CLOCK JOSEPH SMITH DATED 1725.<br />

With in-line trains having rectangular section posts with splayed feet<br />

<strong>and</strong> bolted frame, oak barrels, turned iron collets, the going train<br />

with recoil anchor escapement, the quarter strike train in the centre<br />

with brass countwheel <strong>and</strong> internal brass fly, square brass signature<br />

plaque applied to the centre post engraved <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> <strong>Chester</strong><br />

1725, the hour strike train on the left side with iron countwheel <strong>and</strong><br />

external fly with iron vanes.<br />

THE FRAME: 15½in x 14in x 25in (39.5cm x 36cm x 63.5cm)<br />

Three train turret clocks from this period are particularly rare. The<br />

present example has the added rarity <strong>of</strong> having the going train on<br />

the right side as opposed to the normal position between the<br />

quarter <strong>and</strong> hour trains.<br />

This clock has no ‘drive-<strong>of</strong>f’, so has never driven a dial, indicating time<br />

by its strike <strong>and</strong> ting-tang quarters. Originally its pendulum was wall<br />

mounted.<br />

The clock has returned to <strong>Chester</strong> <strong>and</strong> is in a private collection.

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>’s turret clocks<br />

Location Date Still working in original<br />

location?<br />

<strong>Chester</strong> Cathedral 1725 Now in a private<br />

collection<br />

St Michael’s Church, Shotwick 1726 Yes<br />

Features <strong>of</strong> interest<br />

Three train ting tang clock<br />

1¼ second pendulum<br />

St Peter’s Church, Little Budworth 1727 Yes Much <strong>of</strong> the original documentation<br />

survives.<br />

Fine small clock in good condition<br />

St Lawrence’s Church, Stoak 1732 Not working when we<br />

Single h<strong>and</strong>er<br />

visited but appears to<br />

be complete<br />

St John’s Church, <strong>Chester</strong> 1746 Replaced Three train movement<br />

Now in a private collection<br />

The ‘Rescued clock’ - Not working.<br />

Three train ting tang clock<br />

In a private collection<br />

St Mary’s Church, Tilston 1750 Yes Fine small clock in good condition.<br />

St Nicholas’ Church, Burton 1751 Yes Single h<strong>and</strong>er<br />

St Mary’s Church, Mucklestone - Yes Much altered<br />

St Alban’s Church, Tattenhall - Yes Maybe <strong>Joseph</strong>/Gabriel(1) <strong>Smith</strong><br />

Poulton Hall 1755 Moved a short distance Still owned by the same family.<br />

Single h<strong>and</strong>er<br />

Adlington Hall 1755 Replaced but safely<br />

All clock parts retained<br />

stored<br />

Pengwern Hall - Not working when we<br />

visited but apparently<br />

Requires some restoration<br />

Single h<strong>and</strong>er<br />

complete<br />

Whitmore Hall - Rusted up Still in original location

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> ‘s Domestic Clocks made in <strong>Chester</strong> 1<br />

All <strong>of</strong> <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>s bracket <strong>and</strong> longcase clock movements have<br />

the family style screwed pillars. These are well cast with fine fins.<br />

His early dials are similar to those produced by his father at the<br />

same date, ie they have heavily engraved matted centres <strong>and</strong><br />

wheatear decoration. He utilised a sun motif <strong>and</strong> sometimes birds,<br />

as his father did. These designs are not uniform. For example the<br />

suns are not all to the same pattern. This could indicate different<br />

engravers’ styles, the same engraver, possibly <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong><br />

himself, experimenting with different designs or a combination <strong>of</strong><br />

the two.<br />

The very earliest <strong>Chester</strong> made clocks were signed ‘<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>,<br />

Gloverstone’. Later dials were plain matted with no engraving or<br />

wheatear decoration. Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>’s longcase <strong>and</strong><br />

bracket clocks have the Arabic minute numbers flipped vertically<br />

on the chapter ring; on some, just the 30 st<strong>and</strong>s the ‘right’ way up<br />

instead <strong>of</strong> the more common upside-down arrangement. On other<br />

clocks the 35, 30 <strong>and</strong> 25 are all flipped. We have seen this feature<br />

on a clock by Thomas Hampson, <strong>and</strong> only one other <strong>Chester</strong><br />

maker. This is Robert Jones who had a close working relationship<br />

with <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>.<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>’s turret clocks all run on smaller weights than is<br />

usual for big clocks, <strong>and</strong> similarly, his longcase clocks run with<br />

smaller weights than is usual, four pounds instead <strong>of</strong> the usual<br />

twelve pounds. We know <strong>of</strong> about thirty domestic clocks by<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>. They are almost all either eight day longcases or<br />

verge table clocks (<strong>of</strong>ten later converted to anchor).<br />

The clock was signed <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> Gloverstone<br />

It is the only one we have seen which is signed in this way

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> ‘s Domestic Clocks made in <strong>Chester</strong> 2<br />

This clock came on the market in the USA in October 2015.<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> made many bracket clocks but this one is the first we<br />

have seen with lacquer. It probably dates to the period after 1725<br />

when <strong>Joseph</strong> moved into Gloverstone, but not later than 1740.<br />

These photos <strong>and</strong> those on the next<br />

page are here courtesy <strong>of</strong> the vendor.<br />

George Ormerod’s History <strong>of</strong> the<br />

County Palatine <strong>and</strong> City <strong>of</strong> <strong>Chester</strong>,<br />

1819, has a clear image <strong>of</strong> a family<br />

crest which resembles that in the<br />

arch <strong>of</strong> this clock. See a photo <strong>and</strong><br />

sketch <strong>of</strong> the crest on the next page.<br />

Lacquer finish table clock by <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>

The photos do not show it well, but a silver<br />

cartouche engraved with a coat <strong>of</strong> arms is in the<br />

arch. We believe these are the arms <strong>of</strong> the Egerton<br />

family whose presence in Cheshire dates back over<br />

a thous<strong>and</strong> years. (See sketch, right.) A branch <strong>of</strong><br />

the family lived at Oulton Park where a baroque<br />

mansion was built for John Egerton in 1716. This<br />

was in the parish <strong>of</strong> Little Budworth, Cheshire,<br />

where the church <strong>of</strong> St Peter, has a clock by <strong>Joseph</strong><br />

<strong>Smith</strong>, dated 1727, the agreement for which was<br />

signed by John Egerton <strong>and</strong> the clockmaker. The<br />

mansion burned down in 1926; the grounds now<br />

house a motor racing circuit. We believe the<br />

bracket clock was made for John Egerton.

During autumn 2014, we heard from a<br />

collector who had bought a bracket<br />

clock made by <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>. It is a<br />

timepiece, with Knibb-type repeat.<br />

When a cord is pulled, the last hour is<br />

struck, followed by the last quarter<br />

(ting tang). It was probably made<br />

during the period between 1725 <strong>and</strong><br />

1740.<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> ‘s Domestic Clocks made in <strong>Chester</strong> 3<br />

The image far right shows the clock<br />

after restoration; the other three<br />

images were taken before any work<br />

was done.<br />

Thanks to the generosity <strong>of</strong> the owner,<br />

we are able to include these images.<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong><br />

table clock

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> ‘s Domestic Clocks made in <strong>Chester</strong> 4<br />

Longcase clock with rolling moon made c 1725<br />

This longcase has several features on its dial<br />

which are seen on clocks by Gabriel <strong>Smith</strong>, ie<br />

1. Wheatear engraving around the dial square<br />

2. Wheatear around the dial centre, seconds<br />

dial <strong>and</strong> calendar aperture<br />

3. Engraving around the arch <strong>and</strong> winding<br />

holes, on the moon humps <strong>and</strong> in the<br />

seconds dial centre<br />

4. Birds<br />

5. A sun<br />

6. Narrow minute b<strong>and</strong><br />

7. Early style silvered moon with stars<br />

8. Fleur de lys<br />

9. Two narrow, finely marked minute rings<br />

Unlike Gabriel’s cases which were mostly made <strong>of</strong><br />

oak, this is made <strong>of</strong> American red walnut. This<br />

timber was used on many <strong>Chester</strong> longcases <strong>of</strong><br />

the period as it was shipped into Liverpool as<br />

ballast on vessels returning from the Americas.

Longcase clock with penny moon made 1725-35<br />

held by Grosvenor Museum, <strong>Chester</strong><br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> ‘s Domestic Clocks made in <strong>Chester</strong> 5 <strong>and</strong> 6<br />

Detail <strong>of</strong> penny moon made 1725-35<br />

from another dial.

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> ‘s Domestic Clocks made in <strong>Chester</strong> 7<br />

Three train longcase clock<br />

Another <strong>of</strong> <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>'s clocks was discovered in<br />

late 2014. It is a three train, full quarter chiming<br />

longcase clock with a very fine movement <strong>and</strong><br />

beautiful walnut case. The plain matted centre <strong>of</strong> the<br />

dial is finely engraved with two flying birds.<br />

This clock was probably made during the 1740s. This<br />

is the only three train longcase by <strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> we<br />

know <strong>of</strong>, despite having been interested in his clocks<br />

for at least the last twenty years.

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> ‘s Domestic Clocks made in <strong>Chester</strong> 8<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong> two train table clock with alarm <strong>and</strong> five minute repeat<br />

From the Bonhams’ catalogue ‘Fine Clocks’ auction, 11 July 2018.<br />

Lot 59 A FINE AND RARE MID 18TH CENTURY FIVE-MINUTE REPEATING MAHOG-<br />

ANY TABLE CLOCK WITH ALARM, MOON PHASE INDICATION AND EXHIBITION<br />

PROVENANCE<br />

<strong>Joseph</strong> <strong>Smith</strong>, <strong>Chester</strong>.<br />

The bold h<strong>and</strong>le over a stepped moulded caddy with gadrooned border over outset<br />

corners with reeded <strong>and</strong> carved Corinthian columns raised on carved ogee bases,<br />

each side with a hinged <strong>and</strong> lockable glazed door to access the movement, the 9.75<br />

inch arched brass dial with flowing foliate scroll engraved border framing the<br />

painted rolling moonphase, the rococo sp<strong>and</strong>rels enclosing the silvered Roman <strong>and</strong><br />

Arabic chapter ring with finely matted centre with alarm setting disc <strong>and</strong> chamfered<br />

date aperture, signed ‘Jos: <strong>Smith</strong>, CHESTER’ between V <strong>and</strong> VII, a lever visible in the<br />

mask by IX which sets the alarm (<strong>and</strong> in doing so, silences the hourly strike), the<br />

twin gut fusee movement with five turned finned pillars screwed through the backplate<br />

<strong>and</strong> pinned to the front, now converted to anchor escapement, with<br />

countwheel strike acting on a single bell, the alarm <strong>and</strong> repeat using three further<br />

hammers <strong>and</strong> two smaller bells, 58cms (23ins) high.<br />

Exhibited: ‘Time & Place: English Country Clocks, 1600-1840’, an exhibition by The<br />

Antiquarian Horological Society at The Museum <strong>of</strong> the History <strong>of</strong> Science, University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Oxford, 25 November 2006 - 15 April 2007. Exhibit number 43.<br />

This imposing <strong>and</strong> innovative provincial clock was one <strong>of</strong> 68 exhibits selected to<br />

show the best <strong>of</strong> provincial horology over nearly two <strong>and</strong> a half centuries. Illustrated<br />

over four pages, the clock is described in the exhibition catalogue. The alarm<br />

does not have a separate power source <strong>and</strong> so when it sounds, it strikes the number<br />

<strong>of</strong> ‘lost hours’ i.e., those that would have struck since the alarm was set. This action<br />

ingeniously brings the countwheel back into synchronization. Quarter repeating<br />

clocks were not uncommon in the mid 18th century, but five-minute repeating examples<br />

are extremely rare.

More to follow