Makivik Magazine Issue 112

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

had made a film about traditional tattoos and watching it, thinking about<br />

it, Weetaluktuk realized it was something she had to do.<br />

“I believe very much in Inuit identity and having as much as we can<br />

that we can sustain in this time,” she says. That made her realize, “I’m<br />

going to do that because I believe in that.”<br />

The reaction, Weetaluktuk says, has been mostly positive. A few people<br />

have high-fived her in stores and a bus driver even told her, “Wow, I love<br />

seeing people who are so into their cultures, who dedicate themselves.”<br />

Diving into her culture is part of what Weetaluktuk enjoys about<br />

working on “3,000.” That, she admits with a laugh, and being able to do<br />

research in the North and spend time with her nieces there.<br />

“To get to do something that could also be good for them,” she says,<br />

trailing off. “I love them.”<br />

There have been so many stages to her documentary project already,<br />

says Weetaluktuk. She started with research and writing, then she began<br />

filming and finding the right soundtrack and the right images. It’s a whole,<br />

lengthy process, but she says, “I love every single part of it.”<br />

Documentaries are, Weetaluktuk believes, one of the best ways to<br />

communicate with people.<br />

“I’ve always been thinking about what are good ways to communicate<br />

with people, what are good ways to communicate ideas,” she says, “and<br />

I think film is especially good for me, because it starts with research<br />

and writing.”<br />

To communicate well you have to really know what you’re talking<br />

about, a process that requires an abundance of research to figure out the<br />

source material to draw from and then plenty of writing to ensure that<br />

what you actually put in front of an audience is the right combination<br />

of words and clips and images to tell an effective story.<br />

A documentary gives you that time, Weetaluktuk says.<br />

“You have the time to be able to learn and make sure you know as<br />

much as you can before you communicate,” she says. “Not every artist’s<br />

practice or everything you do in life gives you the time to have enough<br />

time to be able to really know what you’re talking about.”<br />

It’s especially important for her, Weetaluktuk says, because she didn’t<br />

grow up learning about Inuit tradition and culture in school. Much of<br />

her knowledge is self-taught. But the archival discovery, she says, has<br />

been incredible.<br />

“I got to see so many beautiful things,” Weetaluktuk says. “One of<br />

my favourite shots is a man icing the bottom of his [qamutik/sled] and<br />

that’s so beautiful.”<br />

That magic of seeing a shot so beautiful that is so representative of<br />

your culture and tradition is something she wants other Inuit youth to<br />

experience.<br />

“Everything” is Weetaluktuk’s inspiration.<br />

“The world is so beautiful and there are so many amazing and beautiful<br />

things and [we], Inuit, are not always shown that,” she says, starting to<br />

cry. “It’s inspirational to try to make a little light for us.”<br />

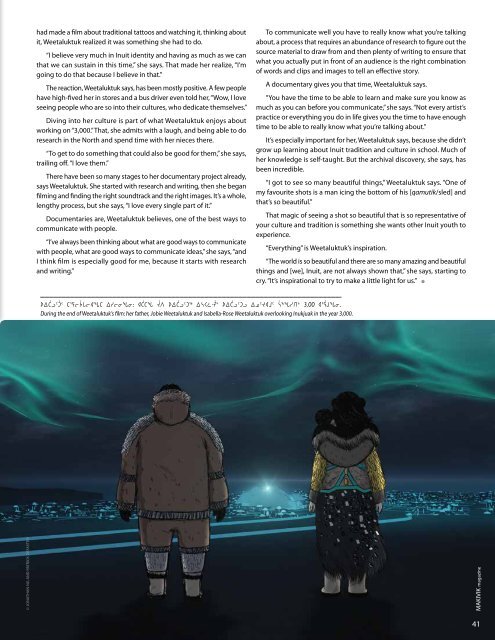

ᐅᐃᑖᓗᑦᑑᑉ ᑕᕐᕋᓕᔮᒐᓕᐊᖓᑕ ᐃᓱᓕᓂᖓᓂ: ᐊᑖᑕᖓ ᔫᐱ ᐅᐃᑖᓗᑦᑐᖅ ᐃᓴᐸᓛ-ᕉᔅ ᐅᐃᑖᓗᑦᑐᓗ ᐃᓄᑦᔪᐊᒧᑦ ᓵᖕᖓᓱᑎᒃ 3,00 ᐊᕐᕌᒍᖓᓂ.<br />

During the end of Weetaluktuk’s film: her father, Jobie Weetaluktuk and Isabella-Rose Weetaluktuk overlooking Inukjuak in the year 3,000.<br />

© JONATHAN NG AND PATRICK DEFASTEN<br />

MAKIVIK mag a zine<br />

41