topos113

uban mutation

uban mutation

Sie wollen auch ein ePaper? Erhöhen Sie die Reichweite Ihrer Titel.

YUMPU macht aus Druck-PDFs automatisch weboptimierte ePaper, die Google liebt.

no 113<br />

2020<br />

to po s.<br />

24 UNMUTE THE<br />

SOUND OF MUTATION<br />

– Eric Firley on planning<br />

scenarios that maintain<br />

relevance in the future –<br />

a future possibly mutated<br />

by climate change<br />

urban<br />

mutations<br />

44 URBAN GROWTH<br />

AND URBAN POVERTY<br />

– Jimena Martignoni on<br />

the fight of Buenos Aires<br />

against urban poverty<br />

and inequality<br />

98 CONTAINER-<br />

IZATION<br />

– Charlie Clemoes on<br />

the shipping container as<br />

a driver of urban change

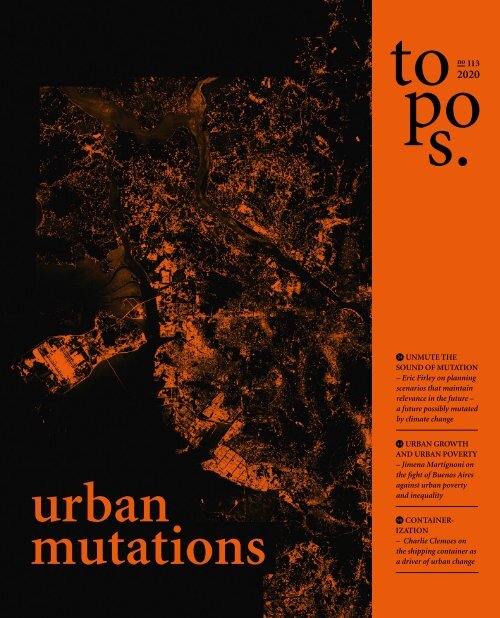

no 113<br />

IZATION<br />

Photo: Rafael Luna<br />

COVER<br />

THE MEGALOPOLIS OF SEOUL<br />

BY RAFAEL LUNA<br />

The mutation of a megalopolis: with nearly ten<br />

million inhabitants, South Korea´s capital city of<br />

Seoul is a megacity. During a period spanning<br />

more than six centuries, Seoul has seen<br />

tumultuous urban transformations due to drastic<br />

social, economic, and political shifts. Read the<br />

article of Rafael Luna on page 76.<br />

urban<br />

mutations<br />

to po s.<br />

2020<br />

24 UNMUTE THE<br />

SOUND OF MUTATION<br />

– Eric Firley on planning<br />

scenarios that maintain<br />

relevance in the future –<br />

a future possibly mutated<br />

by climate change<br />

4 URBAN GROWTH<br />

AND URBAN POVERTY<br />

– Jimena Martignoni on<br />

the fight of Buenos Aires<br />

against urban poverty<br />

and inequality<br />

98 CONTAINER-<br />

– Charlie Clemoes on<br />

the shipping container as<br />

a driver of urban change<br />

TOPOS E-PAPER: AVAIL-<br />

ABLE FOR YOUR DESKTOP<br />

For more information visit:<br />

www.toposmagazine.com/epaper<br />

Admittedly, dealing with the<br />

topic of urban mutations is<br />

anything but easy. And why<br />

would we choose this topic<br />

and call on numerous authors<br />

and ask them to rack their<br />

brains over it? Because we<br />

want to talk about change,<br />

about transformation, and we want to dig deeper. The<br />

fact is, urban spaces are subject to constant change.<br />

They grow, flourish and shrink; their layers overlap.<br />

Crises, economic recessions and upturns, urbanisation<br />

and climate change all transform the look of urban<br />

spaces. By 2050 two-thirds of the world’s population<br />

will live in cities. The consequences of urbanisation<br />

are already visible everywhere, i.e. the struggle for<br />

open space, for greenery, for resources, for a raison<br />

d'être, for equality, and often simply the struggle for<br />

survival. This is especially the case in megacities,<br />

where borders, lines, spaces and entire areas are constantly<br />

expanding and shifting in an uncontrolled and<br />

intensive manner. In order to analyse these transformation<br />

processes, we have put forth an analogy that is<br />

somewhat daring, but which certainly has its qualities<br />

as an object of discussion and analysis: We define the<br />

city as a living organism; as an organism with its own<br />

metabolism, an organism that moves, grows, changes<br />

and breathes, in whose veins no blood flows but instead<br />

water and electricity, etc., an organism which is<br />

sometimes asleep, and sometimes wide awake. And if<br />

mutation is by definition “...the spontaneous or deliberate<br />

change of genetic material, i.e. the entire genetic<br />

material of an organism,” and is also considered an<br />

anomaly, then urban mutation could also be a departure<br />

from the normal state, from the norm: the deliberate<br />

or spontaneous change of the genetic material<br />

of urban space. But what is the genetic material of a<br />

city? If you look at it from the perspective of urban<br />

morphology, the genetic code of a city is probably its<br />

ground plan, its streets, parks, buildings and squares.<br />

Like living organisms, cities are constantly renewing<br />

ANJA KOLLER<br />

Editor<br />

a.koller@georg-media.de<br />

their cells; these renewals are usually carried out according<br />

to standards, but not always. At certain locations,<br />

given the right conditions, certain changes in<br />

the system may occur. And these changes, in turn,<br />

have a transforming effect on those who have to live<br />

with them. Climate change and associated extreme<br />

weather events, air pollution, urban growth, economic<br />

decline, economic aspirations, cultural influences,<br />

inventions, the increasing polarisation between rich<br />

and poor and health crisis all change the cell tissue of<br />

urban spaces. It’s the architects, urban planners and<br />

landscape architects, who, through their work, react<br />

to these dynamics and changes by initiating transformation<br />

processes themselves. It’s no coincidence that<br />

this view of urban “growths” and “transformations”<br />

also includes megacities and, ultimately, especially the<br />

Global South. According to the UN, more than 10<br />

million people live in each of the urban agglomerations<br />

located there. And due to rapid urbanisation, 34<br />

of the world’s 41 megacities are expected to be in the<br />

Global South by 2030, and are the places where accelerated,<br />

and to a certain extent uncontrolled, growth occurs.<br />

This is where planners need to be innovative in<br />

order to respond to the ecological, social and economic<br />

challenges faced by inhabitants. Nevertheless, we also<br />

look at the Western world, at the problem of air pollution<br />

in Barcelona, at the effects of climate change in<br />

Miami, at wildfire disasters in California, and at the<br />

transformation of post-industrial landscapes.<br />

Dear readers, the topic of urban mutations marks<br />

the finale of 2020, indeed a very special year. My editorial<br />

colleagues and I would like to take this opportunity<br />

to thank you all. And speaking of changes: Be even<br />

more critical than you already are and don’t forget: “If<br />

we are unable to practice citymaking with hope and<br />

inspiration for a humanist future, we might soon be<br />

replaced by fully technocratic and data-centred alternatives<br />

like Sidewalk Labs, which offer conflict-free<br />

and consumer-driven solutions”, says Eric Firley in his<br />

lead article. We are happy to concur with him on this.<br />

Stay healthy, and all the best for the year to come.<br />

topos 005

Contents<br />

THE BIG PICTURE<br />

Page 8<br />

OPINION<br />

Page 10<br />

TALENT VS. MASTERMIND<br />

Page 12<br />

CURATED PRODUCTS<br />

Page 104<br />

REFERENCE<br />

Page 108<br />

EDITOR’S PICK<br />

Page 110<br />

METROPOLIS EXPLAINED<br />

Page 14<br />

A BREATH OF FRESH AIR<br />

THE PROJECT AIR/ARIA/AIRE<br />

Page 30<br />

COLLAGES OF ARCHITECTURE<br />

Focusing on the complexity of city life by use of collages:<br />

Klaus Theo Brenner’s new book City Life Collage<br />

Page 18<br />

UNEARTHING WATER<br />

Making water more perceptible: Mexico City and the<br />

need for architecture that presents water in a new context<br />

Page 64<br />

UNMUTE THE SOUND OF MUTATION<br />

Eric Firley on planning scenarios that maintain relevance<br />

in the future: How Miami tackles climate change<br />

Page 24<br />

A BREATH OF FRESH AIR<br />

The impact of air pollution on city dwellers’ health:<br />

The project Air/Aria/Aire and the case of Barcelona<br />

Page 30<br />

“THE PRODUCTION OF ... EQUITABLE AND<br />

INCLUSIVE ENVIRONMENTS”<br />

Bianca Maria Rinaldi on the relevance of public green<br />

spaces in growing and socially fragmented cities<br />

Page 36<br />

SHAPING THE GLOBAL SOUTH<br />

Deden Rukmana on the need for including informal<br />

spaces in planning scenarios in the Global South<br />

Page 38<br />

URBAN GROWTH AND URBAN POVERTY<br />

The decades-long fight of the city of Buenos Aires against<br />

urban poverty and inequality<br />

Page 44<br />

LEVERAGES TO LIVEABILITY<br />

Urban activist Olamide Udoma-Ejorh on the challenges of<br />

urban development in the megacity of Lagos<br />

Page 52<br />

FACTS & FIGURES<br />

Page 56<br />

MUTATION THROUGH REGENERATION<br />

The case of Semarang, Java: examining local improvement<br />

attempts as reactions to global trends of urban regeneration<br />

Page 58<br />

THE DIALECTIC OF TRANSFORMATION<br />

AND PERMANENCE<br />

On China’s rapid growth and the urban planning strategy<br />

of modernizing its traditions<br />

Page 70<br />

INSULAR STRUCTURES<br />

The megalopolis of Seoul: Analyzing urban mutations<br />

based on the city’s typological subunits<br />

Page 76<br />

POSTMODERN PYROSCAPES<br />

On the need for a future-proof fire culture in the<br />

wildfire-shaken state of California<br />

Page 82<br />

“IT TAKES COURAGE TO USE A<br />

LANDSCAPE AS IT IS”<br />

In conversation with Tilman Latz on the challenges of the<br />

transformation of post-industrial landscapes<br />

Page 86<br />

RELOCATING A CITY<br />

About moving the arctic city of Kiruna, redefining values<br />

and finding solutions for a world of constant change<br />

Page 92<br />

CONTAINERIZATION<br />

Charlie Clemoes on the shipping container<br />

as a driver of urban change<br />

Page 98<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Page 102<br />

ESCAPE PLAN<br />

Page 112<br />

EDGE CITY<br />

Page 114<br />

IMPRINT<br />

Page 113<br />

BUENOS AIRES: URBAN GROWTH<br />

AND URBAN POVERTY<br />

Page 44<br />

Photos: Secretaría de Desarrollo Urbano, Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires (below); Illustration: 300.000km/s (above)<br />

006 topos ISSUE 113

OPINION<br />

Sigrid Ehrmann<br />

Environmental Planner & Landscape Architect<br />

“WILL THE NEW<br />

EUROPEAN BAU-<br />

HAUS BE THE FIRST<br />

STEP TO CREATING<br />

SUSTAINABLE,<br />

RESILIENT AND<br />

EQUITABLE CITIES?”<br />

“Good design can improve lives” is a catchphrase reminiscent of the influential<br />

German design school Bauhaus founded by Walter Gropius in 1919, which last<br />

year celebrated its 100th anniversary. With her appeal for a “new European<br />

Green Deal aesthetic combining good design with sustainability”, European<br />

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen unveiled the Commission’s plans<br />

to revive the Bauhaus idea.<br />

010 topos ISSUE 113

Opinion<br />

The New European Bauhaus forms part of the<br />

European Green Deal’s action plan that aims to<br />

reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55 per cent<br />

by 2030 and make Europe climate-neutral by<br />

2050. It will be financed through the EU’s 750<br />

billion-euro NextGenerationEU coronavirus recovery<br />

plan. In her State of the Union address<br />

Ursula von der Leyen called for a “Renovation<br />

Wave” to help Europe move to a circular economy.<br />

She stressed the importance of the project’s<br />

environmental, economic and cultural aspects,<br />

as well as the new Bauhaus’ role as “a co-creation<br />

space where architects, artists, students, engineers,<br />

designers work together to make that happen”.<br />

With the announcement, the Commission<br />

acknowledged two notable points. Firstly, the<br />

idea of Baukultur – architecture and construction<br />

as a cultural activity including its social, economic,<br />

ecological and aesthetic dimension – and<br />

its importance to society, which had been previously<br />

recognised by European Ministers of Culture<br />

in their Davos Declaration in 2018. And secondly,<br />

the key role the construction industry<br />

plays in emissions reduction and the creation of<br />

sustainable and climate-neutral cities and communities.<br />

Buildings account for around 40 per<br />

cent of the EU’s energy consumption and 36 per<br />

cent of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions. With<br />

its Renovation Wave strategy, the EU aims to improve<br />

the energy performance of buildings<br />

through stronger regulations and the use of innovative<br />

materials, create green jobs and promote<br />

neighbourhood-based approaches and affordable<br />

housing. The New European Bauhaus<br />

“is intended to be a bridge between the world of<br />

science and technology and the world of art and<br />

culture”. Many details of this vision of a 21 st century<br />

Bauhaus remain hazy. A recently published<br />

fact sheet describes the New European Bauhaus<br />

as a forum for discussion, a space for art and culture,<br />

an experimentation lab, a hub for global<br />

networks and experts, and a contact point for<br />

citizens. In the initial stages, five projects will be<br />

created in different member states of the Union.<br />

The second phase from 2023 onwards will seek<br />

to establish projects and a network both inside<br />

and outside Europe. These pilot projects will focus<br />

on aspects such as natural building materials,<br />

energy efficiency, mobility and digital innovation.<br />

While a further exploration of natural and<br />

sustainable materials as well as the principles of a<br />

circular economy in architecture is commendable,<br />

a lack of political will to enforce a green<br />

transformation of the building sector is arguably<br />

more problematic. Can the European Green<br />

Deal lead to a change in policies and a muchneeded<br />

reform of the construction industry – a<br />

sector that is known to be slow to innovate?<br />

Though the original Bauhaus might not provide<br />

a model for ecological design, its holistic approach,<br />

experimental and innovative character<br />

and ideal of a socially responsible society could<br />

point the way. Beyond its aesthetic, the Bauhaus<br />

had an important political dimension. Its influence<br />

on both architecture and society is still apparent<br />

today. A New European Bauhaus that<br />

draws on the collective spirit of its predecessor<br />

and is based on co-creation and co-design might<br />

be lead to broad engagement and build “a tomorrow<br />

that is greener, more beautiful and humane”,<br />

as suggested by von der Leyen. The New<br />

European Bauhaus’ impact is supposed to reach<br />

beyond Europe’s borders, as “Europe is to lead<br />

the way in the twin green and digital transition”.<br />

A dialogue between cities on a global level is desirable,<br />

yet it needs to be a two-way conversation.<br />

There is much we can learn from cities in the<br />

Global South with regard to climate change adaptation,<br />

community building, rapid urbanisation<br />

and resilience. Good design can indeed improve<br />

lives. During the current pandemic crisis,<br />

the need for affordable high-quality housing and<br />

accessible green public space has become evident.<br />

We have to rethink how we build and inhabit<br />

our cities. Whether the European Green<br />

Deal and the New European Bauhaus can lead to<br />

systemic change and fight climate change, as it<br />

claims, remains to be seen. The EU’s credibility<br />

has been undermined by the recent approval of a<br />

new EU agricultural policy that critics claim will<br />

worsen the climate crisis, while EU environment<br />

ministers failed to strike a deal on its 2030 emissions<br />

reduction target. What has become clear is<br />

that to bring about systematic change and create<br />

sustainable, resilient and equitable cities, architects<br />

and urban designers need to be involved in<br />

decision-making processes. Let’s hope that the<br />

New European Bauhaus will be the first step.<br />

SIGRID EHRMANN holds a diploma degree in<br />

landscape architecture of the Technical University of<br />

Berlin. She works as a freelance landscape architect,<br />

environmental planner and writer. Based<br />

in Barcelona, a city renowned for its architecture,<br />

innovative urban transformations and creative<br />

scene, she conducts research on a variety of topics,<br />

ranging from climate change adaptation, green<br />

infrastructure and urban strategies to detailed<br />

landscape architecture and public space projects.<br />

topos 011

urban mutations<br />

Collages of<br />

Architecture<br />

Is it possible or even reasonable to deliberate on architecture without<br />

paying attention to the surroundings, to the space architecture<br />

is embedded in? Klaus Theo Brenner, German architect, would<br />

definitely deny this notion. He sees himself in the tradition of the<br />

Italian architect and designer Vittorio Gregotti, and therefore,<br />

when talking about architecture always includes urban space. For<br />

him, architecture is always connected to the urban realm and interrelated<br />

with the urbanites. In his recent book “City Life Collage”<br />

Brenner focuses on the complexity, vibrance and diversity of city<br />

life by use of collages that he created between 1990 and 2019. He<br />

creates highly aesthetic, colorful, sometimes nostalgic, sometimes<br />

alienated, even mutated images that tell stories about the cities we<br />

currently inhabit and about the cities’ past, always shimmering<br />

through. Just as cities are constituted by different layers, transforming<br />

the urban realm’s structure and surface over time,<br />

Brenner builds layer upon layer to create a plethora of palimpsests<br />

to give the beholder of the collages an idea of both the mutability<br />

and consistency of urban space.<br />

ANJA KOLLER<br />

Collages: Klaus Theo Brenner<br />

018 topos ISSUE 113

“The collaged view of the urban space suddenly allows us to see utilitarian everyday space and artificial architecture side by side, at different stages of their<br />

execution, without the fiction of a pseudo-space leading us astray. In doing so, the collage deliberately disrupts our customary way of looking at things: it is an<br />

experimental representation of elements that cannot normally be seen together at the same time, despite being interrelated.”<br />

Taken from the paragraph“The essence of architectural space – Flatland and Aleph” by Jan Büchsenschuß from the book “City Life Collage”<br />

topos 019

030 topos ISSUE 113

urban mutations<br />

The city of Barcelona<br />

consistently breaches<br />

EU rules on nitrogen<br />

dioxide values and has<br />

been referred to the<br />

Court of Justice<br />

because of poor air<br />

quality.<br />

Barcelona redrawn by air<br />

pollution, 2020: Using<br />

Barcelona as a case<br />

study, the project Air/<br />

Aria/Aire analyses data<br />

sets to showcase the<br />

impact air pollution has<br />

on the city (below).<br />

A<br />

Breath<br />

When it comes to air pollution, cities are fighting a permanent pandemic. In light of the<br />

magnitude of the problem, Barcelona architect and curator Olga Subirós recognised the<br />

urgency of addressing the climate crisis and public health emergency from an urbanistic<br />

point of view. Using Barcelona as a case study, the project Air/Aria/Aire analyses data sets<br />

to showcase the impact of air pollution from the urban scale down to the street level. An<br />

exhibition about Air/Aria/Aire, curated by Olga Subirós, will be presented at the<br />

International Architecture Exhibition 2021 in Venice, exploring the notion of air as a common<br />

good that is vital to people’s health and striving to respond to the Biennale’s theme of<br />

‘How will we live together?’ – an even more vital question in times of coronavirus.<br />

SIGRID EHRMANN<br />

Photo: Illustration 300.000km/s; Jon Tugores (above)<br />

of<br />

Fresh Air<br />

topos 031

urban mutations<br />

Informal settlements<br />

such as Jakarta are<br />

frequently located<br />

around, or in the vicinity<br />

of, exclusive residential<br />

high-rises in inner-city<br />

areas or gated<br />

communities in urban<br />

peripheral areas.<br />

038 topos ISSUE 113

Shaping the Global South<br />

Decades of massive population growth and rural-to-urban migration have accelerated<br />

urbanization in the Global South and produced cities of unprecedented size and density.<br />

By 2030 developing countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America are projected to<br />

be home to 34 out of the world’s 41 megacities. Developing these “urban fields” and<br />

turning them into livable and sustainable areas of habitation involves complex undertakings<br />

the significance of which extends the borders of individual countries. Deden<br />

Rukmana, editor of The Routledge Handbook of Planning Megacities in the Global<br />

South, describes the challenges that lie ahead and presents innovative urban development<br />

and planning initiatives. He focuses especially on informal spaces, which are the<br />

largest physical feature of cities throughout the Global South.<br />

DEDEN RUKMANA<br />

Photo: Deden Rukmana<br />

topos 039

urban mutations<br />

One of the poorest<br />

unplanned settlements<br />

in the southern part of<br />

Buenos Aires, prior its<br />

partial revitalisation:<br />

the large building,<br />

abandoned for decades,<br />

was demolished and<br />

replaced by the new<br />

structure of the Social<br />

Development Ministry.<br />

Urban<br />

Growth<br />

Cities are growing and so is urban poverty. The 2030 Agenda<br />

for Sustainable Development determined that ending poverty<br />

should be the Sustainable Development Goal #1. The City of<br />

Buenos Aires has been fighting against the urban poverty and<br />

inequality that it is confronted with for almost a century. The exploration<br />

of historic disparities between the city’s northern and<br />

southern areas, social behavior and apparently unchangeable<br />

urban stigmata has led to ideas and possible ways to develop a<br />

more equitable urban planning model that also tackles poverty.<br />

JIMENA MARTIGNONI<br />

and urban<br />

Poverty<br />

Photo: Secretaría de Desarrollo Urbano, Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires.<br />

044 topos ISSUE 113

topos 045

urban mutations<br />

Leverages<br />

A more inclusive, liveable and sustainable Lagos – is that<br />

possible? The ever-growing Nigerian capital has had to<br />

deal with manifold social, political, infrastructural and<br />

environmental challenges that hamper an urban development<br />

benefitting first and foremost the people. Urban activist<br />

and director of the Lagos Urban Development Initiative<br />

(LUDI), Olamide Udoma-Ejorh, implements smallscale<br />

community-based projects as a leverage towards liveability,<br />

inclusivity and sustainability. For topos, she takes a<br />

critical look both at the Lagos State Development Plan<br />

(LSDP) 2012–2025 aimed at turning Lagos into Africa’s<br />

model megacity and the projects that come with it.<br />

OLAMIDE UDOMA-EJORH<br />

to<br />

Liveability<br />

052 topos ISSUE 113

Photo: By Jacobchikaike1 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=88697548 - image has been transformed - horizontally flipped<br />

The rapidity of<br />

population growth in<br />

Lagos, Nigeria creates<br />

adverse effects at many<br />

levels, such as at the<br />

level of public<br />

transportation and<br />

traffic congestion.<br />

topos 053

Mutation<br />

through<br />

Regeneration<br />

FELICITAS HILLMANN, WIWANDARI HANDAYANI<br />

AND BINTANG SEPTIARANI<br />

Photos: Felicitas Hillmann<br />

058 topos ISSUE 112

The glocalisation of planning has led to the<br />

phenomenon that planning concepts are<br />

copied all over the world. Tools that are used<br />

in the Global North are implemented in the<br />

Global South and vice versa. The field of<br />

urban regeneration is no exception: it has<br />

become a matter of “planned glocal mutation”.<br />

By identifying and examining local<br />

development and improvement attempts as<br />

reactions to global trends of regeneration<br />

strategies, three urban development projects in<br />

Semarang, Java offer related insight. The main<br />

question is, what role does the mobilization<br />

and participation of the local population play<br />

in establishing successful urban regeneration<br />

programs?<br />

Urban regeneration:<br />

The improvement of<br />

marginalized urban<br />

neighborhoods in<br />

Semarang is comprised<br />

of various regeneration<br />

schemes designed to<br />

reconcile the needs of<br />

the resident population<br />

with the integration of<br />

the city into global<br />

circular flows and<br />

modern urban planning<br />

experiences.<br />

topos 059

urban mutations<br />

The apartment block is a<br />

typological urban insulae<br />

that is repeatedly<br />

employed to produce the<br />

contemporary<br />

megalopolis. The images<br />

show the development of<br />

examples in Seongsu.<br />

Insular<br />

With nearly ten million inhabitants, South Korea’s capital<br />

city of Seoul is a megacity. During a period spanning<br />

more than six centuries, Seoul has seen tumultuous urban<br />

transformations due to drastic social, economic, and<br />

political shifts. Observing the transformation processes<br />

Seoul went through while trying to find an appropriate<br />

definition of the related mechanisms of urban growth,<br />

analyzing urban mutations based on the city’s typological<br />

subunits offers insight. These subunits can be read as<br />

“insulae”, with reference to the housing blocks of ancient<br />

Rome. This peculiar formation provides a contemporary<br />

reading of urban morphology as a typologically expanding<br />

megastructure.<br />

RAFAEL LUNA<br />

Structures<br />

Photo:Rafael Luna<br />

076 topos ISSUE 113

topos 077

“It takes courage to use a landscape as it is”<br />

When industrial landscapes have fulfilled their purpose, are no longer needed, a process begins that goes to the very<br />

substance of things. Not only places, but also people are robbed of their identity; economic, social, societal changes are<br />

inevitable. Where do you start as a planner? How do you set a transformation process in motion? Do you build on what<br />

is still there? Do you break away from it? How much radicalism is needed to transform landscapes in such a way that<br />

a new identity is possible, but the past does not disappear? topos spoke with Tilman Latz, a German architect, urban<br />

planner and landscape architect, about the right way to deal with industrial legacies, about the dangers of the Bilbao<br />

effect and about the great heritage of Duisburg-Nord.<br />

INTERVIEW: ANJA KOLLER<br />

topos: Mr. Latz, one of your areas of expertise is the transformation of post-industrial<br />

landscapes. What does transformation mean to you?<br />

TILMAN LATZ: For some people, transformation is any kind of change. For us,<br />

transformation is something that very much takes on a given situation or at<br />

least tries to do so. In order for something new to emerge, i.e. for the transformation<br />

process to be set in motion, one must deal with the existing. And we<br />

don't only look at what is visible, what is there, but also at the invisible. We look<br />

at thoughts, hopes, clichés that people have in their heads, at the history of a<br />

place, which often has to do with what is visible. We then place this construct in<br />

a new context of meaning.<br />

topos: What happens to the places, the landscapes, and the people until places<br />

are transformed, until you as a planner create a new framework of meaning?<br />

LATZ: A region builds up an industry and suddenly the structures that are so<br />

important for the people there are empty and apparently without any further<br />

meaning – despite the fact that they provided work to many generations and<br />

that billions were invested and earned there. Industrial landscapes, for example,<br />

are per se always subject to constant change so that they can keep up with new<br />

technologies and remain competitive. If this will to change is not there or is no<br />

longer possible due to external circumstances, then decline is inevitable: we observed<br />

this in many industrial areas in eastern Germany, for example – after the<br />

fall of the Berlin Wall, the plants there were hopelessly outgunned in the global<br />

competition. This process is the same all over the world: industrial plants are<br />

shut down, thousands of people lose their jobs. In other words, nothing positive<br />

is associated with what is there; on the contrary, there is frustration and a feeling<br />

of worthlessness. And this is exactly what you have to confront as a planner.<br />

You can take these issues very far: depending on which culture you are dealing<br />

with, you have to handle different hardships and effects – both in terms of people<br />

and the landscape. And I am convinced that you can work with that.<br />

topos: Give us an example – in which project is this process-based and exploratory<br />

element particularly evident? Different phases take place here: shock, perhaps<br />

even a kind of “catatonia”, realisation, recognition, self-discovery, reorientation...<br />

LATZ: Our example is Duisburg-Nord. In the mid-1970s there was a worldwide<br />

steel crisis. Production at the Meiderich steelworks was cut back. The last shift<br />

ended in 1985. That was hard for the people there. The special situation at the<br />

time was – and this is of course still relatively specific to Germany – that social<br />

and economic hardships were cushioned by subsidy systems. This is often not<br />

the case in other countries. Generally speaking, people in Germany tried to<br />

keep the industry running as long as possible. After all, when an important<br />

plant is closed, others will follow; chain reactions are set in motion. That’s why<br />

the shut-down process was carried out slowly and, above all, gradually, by closing<br />

one part of a plant after another. A “cautious” approach was adopted. And<br />

this cushioning on the part of the politicians conveyed an incredible stability<br />

despite all the problems, but above all it also provided the time to deal with<br />

what the process really entailed and to think about alternatives. The planners –<br />

above all my father Peter – still had a lot to work with during the process of<br />

transforming the steelworks into a landscape park. And that was precisely one<br />

of the reasons why the IBA Emscher Park, i.e. the International Building Exhibition<br />

under the leadership of Karl Ganser, a ten-year modernisation programme<br />

by the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia to overcome the<br />

structural crisis in the northern Ruhr area – was so successful.<br />

topos: Then it really depends on the culture of the respective country how to deal<br />

with a transformation process...What are differences and what are similarities?<br />

LATZ: In many countries, people don't take the time to deal intensively with the<br />

object. Often the process is carried out hastily and plants are immediately shut<br />

down, sometimes even demolished. In Germany, people discuss what happens<br />

when identity is lost, because that is viewed as a drastic consequence. But of<br />

course there are similarities beyond all cultural differences, and these are the societal<br />

wounds that the closing down of a plant entails, the stories people tell<br />

about a place, the bond they feel with it. Historically, industrial plants in the<br />

Western industrialised countries were usually an integral part of the city centre<br />

– at least until the Second World War, and thus roughly until the car gained importance<br />

in the 1960s and 1970s. This is where life took place; often the town<br />

hall was right next door. And exactly this was, and still is, an opportunity for<br />

086 topos ISSUE 113

urban mutations<br />

Architect, Landscape<br />

Architect and Urban<br />

Planner Tilman Latz.<br />

VITA<br />

TLMAN LATZ – is partner and design director of Latz + Partner. He studied landscape<br />

architecture at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna and at<br />

the University of Kassel, where he graduated in 1993. He studied architecture at the Architectural<br />

Association in London and at the University of Kassel, where he completed<br />

his studies in 1997 with a diploma in architecture. Subsequently, he worked as a project<br />

manager for Jourda Architectes Paris, as a guest lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania<br />

in Philadelphia and as a guest professor at the University of Kassel. One of his areas<br />

of expertise is the transformation of post-industrial landscapes.<br />

Photo: Latz + Partner<br />

many facilities, because at the moment of their closure they still have a significance<br />

in the urban environment that should not be underestimated. Their privileged<br />

status in the urban fabric is also the basis for the restructuring process of<br />

a region or city towards a new use, towards a change. However, that very same<br />

aspect, the circumstance that the entire infrastructure of a city is geared towards<br />

these industrial sites, brings new challenges for us planners in the process of<br />

transformation. For this reason, infrastructure also needs to be rethought. In<br />

the Ruhr area, this has usually worked well because it emerged almost entirely<br />

from these new industrial cities. And as a result, many former industrial plants<br />

there could become new urban, central locations.<br />

topos: How to find the right lever to identify a new use? When does a conversion<br />

work, when does it not work? There are projects in other countries, such<br />

as the USA, where an approach other than conversion was adopted, where decommissioned<br />

facilities were not put to a new use. Instead, the planners partially<br />

caved in to the investors’ desires, however without the success hoped for.<br />

LATZ: Speaking for the Ruhr area, I can say that conversion was possible and<br />

met with success because many actors actively supported it from the early 1990s<br />

onwards. And it was always a matter of finding a new identity. When something<br />

is lost, when those structures that make up the character of a region or city are<br />

no longer effective, new ideas, new models, a new self-image are needed. All of<br />

this can best be achieved through active conversion. The USA has indeed usually<br />

dealt with the issue differently. This can be seen – and I find this a very sad<br />

example – in the Bethlehem Steel plant in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. A steelworks<br />

covering an area of over a thousand hectares, which is truly unique in my<br />

opinion, but which for me is emblematic of how industrial culture is treated in<br />

the USA. The design and planning such a site requires are often left to private<br />

investors. In England, unfortunately, the situation is similar, as the discussion<br />

about preserving the Redcar Blast Furnace in Middlesbrough shows. Several<br />

generations of students dealt with the Bethlehem Steel site, among them my father<br />

Peter and I when we were teaching in Philadelphia in different years. Over<br />

the years, various architects and planners developed some really interesting<br />

concepts of what a change of use after the closure in 1995 could look like. In the<br />

end, however, only the central blast furnace was left standing, everything around<br />

it was demolished, levelled and turned into a banal business park, including<br />

even a casino, I think. Such a utilisation concept, if you even want to call it that,<br />

is disappointing in my opinion, for the fascinating buildings were fenced in and<br />

remained inaccessible. Only a footbridge allows a certain proximity to this fascinating<br />

monster. You can only look at it from the outside, but – unlike in Duisburg-Nord<br />

– you can’t experience it in a new context, touch it or even climb up it.<br />

topos: Didn't the planners deal with the place and its history?<br />

LATZ: Maybe they did, but apparently that didn't interest the investors. And in<br />

the end, as an architect or landscape architect, you often end up saying, “well, I’ll<br />

just do it somehow”. That’s bitter, but that’s how it works. In addition, cities in<br />

the US often have very little opportunity to influence the process because they<br />

lack the finances. In countries like Germany, you could place the property under<br />

a preservation order, but then the planner is no longer the planner, but the<br />

conservationist, which of course does have its justification. But when this happens,<br />

there is often a lack of understanding for public space, a lack of ideas for a<br />

new use. At Bethlehem Steel, they subjected everything to one goal; they levelled<br />

as much of the space as possible, since the whole thing had to be financed. By<br />

contrast, we at Latz + Partner don't perceive such a facility primarily as a building,<br />

we take in the entire site, viewing it as one landscape. In my opinion, it must<br />

be done in this way because industry zones, especially heavy industry, are machines<br />

where the surrounding landscape, the infrastructure, is absolutely essential,<br />

not only for storing materials, but also to enable the machine to function in<br />

the first place. This is quite different from business park areas consisting of service<br />

facilities, such as DHL or Amazon distribution centres. If the whole is understood<br />

as one coherent landscape, an incredibly exciting space can emerge, in<br />

which business, culture, ecology and housing are all possible to a relevant extent.<br />

In addition, such an approach would enable much more attractive spatial and<br />

functional possibilities, which would have a more lasting effect on a location<br />

than most new planning proposals could ever generate. However, as already<br />

mentioned, all of this depends on the funding made available and of course also<br />

on the willingness or the possibility to embrace such an exciting radicalism.<br />

topos 087