Sie wollen auch ein ePaper? Erhöhen Sie die Reichweite Ihrer Titel.

YUMPU macht aus Druck-PDFs automatisch weboptimierte ePaper, die Google liebt.

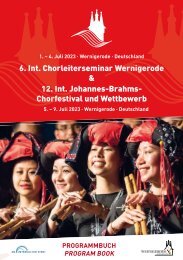

<strong>12.</strong> <strong>Int</strong>ernationales <strong>Johannes</strong>-<strong>Brahms</strong>-<br />

<strong>Chorfestival</strong> <strong>und</strong> <strong>Wettbewerb</strong><br />

ERÖFFNUNGSKONZERT<br />

OPENING CONCERT<br />

MIT DEM MDR-RUNDFUNKCHOR / WITH THE MDR RADIO CHOIR<br />

KONZERTEINFÜHRUNG<br />

CONCERT INTRODUCTION

KONZERTEINFÜHRUNG<br />

Von Raumklang <strong>und</strong> ewigem Licht<br />

Zu den Werken von<br />

Maija Einfelde, Morton Feldman, Thomas Tallis, Jan Sandström, Garth Knox,<br />

Nana Forte <strong>und</strong> György Ligeti<br />

Die Communio in der liturgischen Totenmesse, die mit den Worten »Lux aeterna<br />

luceat eis, Domine« (Das ewige Licht leuchte ihnen, o Herr!) beginnt, inspirierte viele<br />

Komponisten des 20. Jahrh<strong>und</strong>erts, unter ihnen György Ligeti <strong>und</strong> George Crumb. Auch<br />

die litauische Komponistin Maija Einfelde, Tochter einer Organistin <strong>und</strong> eines Orgelbauers<br />

<strong>und</strong> ehemalige Schülerin des bedeutenden lettischen Symphonikers Jānis Ivanos, hat<br />

den um ewiges Licht, vollkommene Ruhe <strong>und</strong> inneren Frieden kreisenden Text vertont –<br />

mit einer konzentrierten Musik voller weicher Harmoniefolgen <strong>und</strong> leuchtenden Farben,<br />

die einen irisierenden Klangzauber verbreitet. Das am 27. April 2012 vom Lettischen<br />

R<strong>und</strong>funkchor unter der Leitung von Kaspars Putniņšin in der Alten Gertruden-Kirche<br />

in Riga uraufgeführte Stück, das heute in einer Version für Chor mit Begleitung von<br />

Glockenspiel erklingt, liegt wie viele Werke Einfeldes auch in anderen Fassungen vor:<br />

für Chor a cappella sowie für Chor <strong>und</strong> Orchester. Die im Kontext klassischer Harmonik<br />

erdachte Musik, die bisweilen auch in expressiv-dissonante Regionen vordringt, steuert<br />

allmählich einem dichten Höhepunkt entgegen, um dann allmählich wieder zur Ruhe zu<br />

kommen. Mit der Bitte um Frieden hebt die Musik erneut an (»Requiem aeternam dona<br />

eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis«), bevor das Werk zwischen Trauer <strong>und</strong> Hoffnung<br />

changierend zu den irisierenden Klängen des Glockenspiels in r<strong>und</strong>em Chorklang endet.<br />

The Rothko Chapel komponierte Morton Feldman 1972 als Hommage an seinen Fre<strong>und</strong><br />

Mark Rothko, der wie Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Barnett<br />

Newman, Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg <strong>und</strong> Philip Guston zu den Malern<br />

der New Yorker Schule gehörte, deren abstrakten Expressionismus Feldman in seine<br />

Musik zu übertragen versuchte: Momente wie »All-over« <strong>und</strong> »Non-relational«, mit<br />

denen Pollocks Gemälde beschrieben wurden, in denen fein gesponnene, kalligraphisch<br />

anmutende <strong>und</strong> in vielen Schichten übereinander liegende Netze aus Farbspuren <strong>und</strong><br />

Farbfäden die Leinwand ohne Ausbildung von Hierarchien oder Blickzentren vollständig<br />

überziehen. Benannt ist das etwa 23-minütige Stück für Schlagzeug, Celesta, Viola,<br />

Sopran, Alt <strong>und</strong> doppelten gemischten Chor nach einer Meditationskapelle der Ménil<br />

Fo<strong>und</strong>ation in Houston, Texas, für die Rothko vierzehn großformatige Bilder angefertigt<br />

hatte. Feldman ließ sich von der eindringlichen Wirkung der Gemälde <strong>und</strong> der besonderen<br />

Architektur der Kapelle inspirieren, wobei seine Musik den ganzen Raum durchdringen<br />

sollte: »Meine Wahl der Instrumente (im Sinne von angewandter Kraft, Balance <strong>und</strong><br />

Klangfarbe«, so Feldman, »war sowohl vom Raum der Kapelle als auch den Gemälden<br />

beeinflusst. Rothkos Bilder gehen bis an den äußersten Rand der Leinwand, <strong>und</strong> ich<br />

wollte den gleichen Effekt mit Musik erreichen – dass sie den ganzen achteckigen<br />

Raum durchdringen <strong>und</strong> nicht aus einer gewissen Distanz gehört werden sollte. Das<br />

Resultat ist dem sehr ähnlich, was man auf einer Schallplatte hört: der Klang ist näher,<br />

körperlicher bei dir als in einem Konzertsaal. Der Gesamtrhythmus der Gemälde, so

DEUTSCH<br />

wie Rothko sie angeordnet hat, schuf eine ungebrochene Kontinuität.« Um einen der<br />

Malerei ebenbürtigen dramatischen Ausdruck zu erzielen, unterteilte Feldman das<br />

Werk in kontrastierende Teile: »Während es bei den Gemälden möglich war, Farbe <strong>und</strong><br />

Abstufung zu wiederholen <strong>und</strong> doch dramatischen Ausdruck zu bewahren, fühlte ich,<br />

dass die Musik eine Reihe äußerst gegensätzlicher Abschnitte brauchte […]: 1. eine<br />

ziemlich lange deklamatorische Eröffnung; 2. ein mehr gleich bleibender ›abstrakter‹<br />

Abschnitt für Chor <strong>und</strong> Glocken; 3. ein motivisches Zwischenspiel für Sopran, Viola <strong>und</strong><br />

Pauken; <strong>und</strong> 4. ein lyrischer Abschluss für Bratsche mit Vibraphonbegleitung, dem sich<br />

später der Chor mit einem Collage-Effekt anschließt.«<br />

Als Nonplusultra der Vokalpolyphonie gilt die Motette Spem in alium von Thomas<br />

Tallis, dem Hoforganisten der Tudors: ein faszinierendes Raumklang-Experiment,<br />

dessen Singularität nur dadurch eingeschränkt wird, dass es die direkte Antwort auf<br />

eine Komposition des italienischen Diplomaten <strong>und</strong> Komponisten Alessandro Striggio<br />

gewesen zu sein scheint, der London 1567 besucht hatte <strong>und</strong> bei dieser Gelegenheit<br />

eine 40-stimmige Motette aufführen ließ. Anschließend stellte der Duke of Norfolk<br />

öffentlich die Frage, ob denn keiner unserer »Englishmen« in der Lage wäre, »so good<br />

a songe« zu schreiben, worauf Tallis mit der Vertonung von Spem in alium antwortete –<br />

ebenfalls für vierzig Stimmen, genauer: für acht fünfstimmige Chöre, die, in Anlehnung<br />

an die venezianische Mehrchörigkeit den Raum akustisch erschließen, der zum Symbol<br />

des göttlichen Kosmos’ wird. Der Duke ließ das Werk vermutlich in seinem Landhaus<br />

Nonsuch Palace aufführen, in dem es einen achteckigen Speisesaal mit vier Emporen<br />

gab – ein Raum, in dem Tallis seine 40 Musiker ideal hätte aufstellen können, um die<br />

raffinierte Klangdramaturgie voll zu entfalten. Denn die Klänge scheinen spiralförmig zu<br />

rotieren (zunächst rechts herum <strong>und</strong> ab »qui irasceris« links herum) <strong>und</strong> korrespondieren<br />

antiphonal miteinander: in vier Gruppen zu zwei Chören, in zwei Gruppen zu vier<br />

Chören sowie in allen möglichen Abstufungen. Nach dieser kaleidoskopartigen Vielfalt<br />

faszinierender Klang- <strong>und</strong> Raumeffekte sorgen nach einem kurzen Moment der Stille<br />

alle Beteiligten für einen imposanten dramatischen Höhepunkt, der den Hörer auch<br />

heute noch ins Zentrum des klingenden Universums rückt.<br />

Das Gloria von Jan Sandström ist Teil der Missa a La Casa de la Madre y el Nino, die<br />

in der Zeit von 1992 <strong>und</strong> 1995 für Erik Westbergs Vokalensemble entstand. Bei dem<br />

besonderen Zusatz im Titel handelt es sich um den Namen eines Waisenhauses in<br />

Bogotá, in dem der schwedische Komponist ein Waisenkind adoptiert hat. Die Idee zum<br />

Gloria kam Sandström, wie er selbst bekannte, in einem Traum, den er so beschrieb:<br />

»In einer Kirche auf einem Berg hoch über Bogotá wiederholte ein Kinderchor<br />

ununterbrochen das Gloria, während mal das eine, mal das andere Kind mit dem Ausruf<br />

›Gloria in excelsis‹ aus der Menge heraustrat.« Diesen Wechsel zwischen Chor <strong>und</strong><br />

Vorsänger findet sich auch in der Komposition – realisiert mit Hilfe mehrere Sopran<strong>und</strong><br />

Tenorsoli, die wie einzelne entrückte Engelstimmen samt Echo wirken <strong>und</strong> die<br />

Raumwirkung durch eine dem Chor gegenüber gestellte Positionierung verstärken.

Sandström, der seine musikalische Karriere als Chorsänger begann <strong>und</strong> ab 1989 an<br />

der der Musikhochschule Piteå als Professor Komposition unterrichtete, schrieb mit<br />

seinem Gloria eine beschwingte Musik voller schillernder Mixturklänge in eingängiger<br />

Harmonik, die die Zuhörer von allen Richtungen her einschließt. Er gilt als führender<br />

Komponist skandinavischer Chormusik, wobei das Weihnachtslied-Arrangement Es ist<br />

ein Ros entsprungen von 1987 zu seinen bekanntesten Arbeiten zählt.<br />

Garth Knox wiederum, einer der führenden <strong>Int</strong>erpreten <strong>und</strong> Komponisten zeitgenössischer<br />

Musik, war viele Jahre Mitglied von Pierre Boulez’ Ensemble <strong>Int</strong>erContemporain <strong>und</strong><br />

Bratscher im Arditti Quartet, was ihm die Möglichkeit gab, eng mit Komponisten wie<br />

Ligeti, Berio, Xenakis oder Cage zusammenzuarbeiten. Mit seinem Quartet for one<br />

komponierte er im Corona-Lockdown im Frühjahr 2020, als alle Konzerte abgesagt<br />

wurden <strong>und</strong> das musizieren in Ensembles verboten war, ein »Streichquartett« für<br />

Viola solo: »So wie einsame Kinder imaginäre Spielgefährten erfinden, um sich selbst<br />

Gesellschaft zu leisten, veranlasste mich mein eigenes enttäuschtes Bedürfnis nach<br />

dem Zusammenspiel mit anderen dazu, einige imaginäre Kollegen zu erfinden <strong>und</strong> auf<br />

unbeschwerte Weise die Möglichkeiten der Aufführung von Kammermusik mit ihnen zu<br />

erk<strong>und</strong>en.«<br />

Das Ergebnis war ein Stück, »das sich im Kopf eines Bratschers abspielt, der davon<br />

träumt, ein Konzert mit einem Streichquartett vor einem großen Publikum zu geben.<br />

Obwohl der Bratschist allein ist, spielt er tatsächlich ein Quartett! Jede der vier Saiten<br />

der Bratsche entspricht einem Instrument des Quartetts, <strong>und</strong> sobald das jeweilige<br />

Instrument einsetzt, setzt sich der Musiker auf dessen Stuhl <strong>und</strong> spielt auf seiner Saite<br />

(die Bühne ist mit vier Pulten <strong>und</strong> vier Stühlen ausgestattet). Um die Fülle des tiefen<br />

Celloklangs zu imitieren, wird die tiefste Saite der Bratsche auf a heruntergestimmt.«<br />

Knox widmete das Werk dem Bratscher Lawrence Power, der das Stück am 18. Juni 2020<br />

in der völlig leeren Royal Festival Hall in London uraufführte.<br />

Die slowenische Komponistin Nana Forte (Jahrgang 1981) schrieb En ego campana<br />

im Auftrag des Schwedischen R<strong>und</strong>funkchors, der das klangvolle Stück für zwei<br />

vierstimmige Chöre am <strong>12.</strong> November 2016 in der Stockholmer Engelbrektskyrkan<br />

uraufführte. Der vertonte lateinische Text stammt aus der Gedichtsammlung Carmina<br />

proverbialia, in Verse gefasste Sprichwörter oder »Weisheiten«, von denen der<br />

slowenische Renaissance-Komponist Jacobus Gallus viele vertont hat. En ego campana«<br />

(Nr. 45) erzählt davon, wie das Läuten der Kirchenglocken die Menschen begleitet, wobei<br />

Nana Fortes Musik mit einfachen <strong>und</strong> sich wiederholenden Klangmuster beginnt. Durch<br />

Veränderungen in Rhythmus <strong>und</strong> Dynamik sowie einer Überlagerung beider Chöre<br />

werden die anfangs einfachen Glockenklänge zunehmend komplexer, wobei auch die<br />

unterschiedlichen im Text reflektierten Emotionen deutlich anklingen.

DEUTSCH<br />

Nana Forte absolvierte ihr Kompositionsstudium an der Musikakademie in Ljubljana, an<br />

der Hochschule für Musik »Carl Maria von Weber« in Dresden sowie an der Universität<br />

der Künste in Berlin. Sie schrieb Orchester- <strong>und</strong> Kammermusikwerke, Stücke für<br />

verschiedene Soloinstrumente <strong>und</strong> Chormusik – bereits während ihres Studiums<br />

arbeitete sie mit vielen slowenischen Chören zusammen, wobei einige ihrer Chorwerke<br />

mit Preisen ausgezeichnet wurden. 2007 vertrat sie die Republik Slowenien im Projekt<br />

»European Ensemble Academy«, das vom Deutschen Musikrat anlässlich der deutschen<br />

Unionspräsidentschaft organisiert wurde. Ihr Libera me für zwei gemischte Chöre war<br />

2009 ein Pflichtstück beim Finale des 5. <strong>Int</strong>ernationalen <strong>Wettbewerb</strong>s für junge Chorleiter<br />

»Europa Cantat« in Ljubljana <strong>und</strong> ist seitdem im Repertoire vieler europäischer Chöre.<br />

Ihre Oper Paradies oder nach Eden nach einem Libretto von Maja Haderlap (in dem<br />

Adam <strong>und</strong> Eva eine Chance zum Neubeginn bekommen) hatte am 22. September 2016<br />

im Vorarlberger Landestheater in Bregenz seine erfolgreiche Premiere.<br />

Demgegenüber sorgte die Uraufführung von György Ligetis Apparitions am 19. Juni 1960<br />

in Köln für einen handfesten Skandal – zu sehr unterschied sich diese Musik vom damaligen<br />

Mainstream der Moderne. Denn in dem Orchesterstück, in dem die Klänge zustandhaft<br />

ineinanderfließen, hatte der aus Ungarn geflohene Komponist erstmals seine Vorstellung<br />

von einer Musik realisiert, in der es »weder Melodien noch Akkorde noch Rhythmen«<br />

gibt. Gleiches gilt für Atmosphères, mit dem Ligeti seinen internationalen Durchbruch<br />

hatte – mit einer in sich fluktuierenden Klangflächenkomposition, in der die Gesetze<br />

der Schwerkraft scheinbar außer Kraft gesetzt werden. Kein W<strong>und</strong>er, das Starregisseur<br />

Stanley Kubrick das Werk in seiner epischen Weltraumparabel 2001: A Space Odyssey<br />

verwendete – ebenso wie Ligetis Lux Aeterna für sechzehnstimmigen Chor von 1966. In<br />

ihm gelang es dem Komponisten, die zuvor in seinem revolutionären Orchesterstücken<br />

erprobten Kompositionstechniken wie Mikropolyphonie <strong>und</strong> Clusterharmonik auf die<br />

Vokalmusik zu übertragen, wobei sich die meditativen harmonischen Gebilde aus einem<br />

fluktuierenden Klangfeld herauskristallisieren. Zudem suggerieren die fluktuierenden<br />

Klänge eine illusionäre Raumtiefe, die sich in die Unendlichkeit zu öffnen scheint.<br />

Formal besteht das Werk aus drei Kanons – zwei achtstimmigen für Sopran <strong>und</strong> Alt<br />

bzw. für Tenor <strong>und</strong> Bass <strong>und</strong> einem vierstimmigen für vier Alti. Die Zäsuren zwischen<br />

den Abschnitten werden durch einen dreistimmigen Pianissimo-Akkord auf dem Wort<br />

»Domine« markiert, der im höchsten <strong>und</strong> bzw. im tiefsten Register erklingt. »Als ich<br />

den Film gesehen habe«, so Ligeti, »war ich begeistert. Ich meine, dass meine Musik<br />

in der Auswahl Kubricks ideal zu diesen Weltraum- <strong>und</strong> Geschwindigkeitsfantasien<br />

passt, die im Film vorkommen.« Da Kubrick die Stücke allerdings ohne Wissen <strong>und</strong><br />

Erlaubnis des Komponisten verwendet hatte, gab es ein unschönes Nachspiel. Metro-<br />

Goldwyn-Mayer erklärte, den avisierten Prozess über einen Streitwert von 30.000 US-<br />

Dollar jahrzehntelang auszudehnen <strong>und</strong> bot Ligeti als »Entschädigung« 1000 Dollar an.<br />

»Schließlich«, so der Komponist, »haben sie 3000 Dollar bezahlt.« Dabei war 2001 der<br />

finanziell erfolgreichste Streifen des Filmjahrs 1968 <strong>und</strong> spielte in den Kinos weltweit<br />

über 190 Millionen US-Dollar ein.<br />

Harald Hodeige

CONCERT INTRODUCTION<br />

Of spatial so<strong>und</strong> and eternal light<br />

On the Works of<br />

Maija Einfelde, Morton Feldman, Thomas Tallis, Jan Sandström, Garth Knox,<br />

Nana Forte and György Ligeti<br />

The communion in the liturgical requiem mass, which begins with the words “Lux<br />

aeterna luceat eis, Domine” (The eternal light shine upon them, O Lord!), inspired many<br />

20 th century composers, among them György Ligeti and George Crumb. The Lithuanian<br />

composer Maija Einfelde, daughter of an organist and an organ builder and former pupil<br />

of the eminent Latvian symphonist Jānis Ivanos, has also set the text, which revolves<br />

aro<strong>und</strong> eternal light, perfect tranquillity and inner peace, to music - with concentrated<br />

music full of soft harmonic sequences and luminous colours that spread an iridescent<br />

so<strong>und</strong> magic. The piece, which was premiered on 27 April 2012 by the Latvian Radio<br />

Choir <strong>und</strong>er the direction of Kaspars Putniņšin in the Old Gertruden Church in Riga, and<br />

which is heard today in a version for choir accompanied by glockenspiel, is, like many<br />

of Einfelde‘s works, also available in other versions: for choir a cappella as well as for<br />

choir and orchestra. The music, conceived in the context of classical harmony, which<br />

at times also penetrates into expressive-dissonant regions, gradually heads towards a<br />

dense climax, only to gradually come to rest again. The music rises again with a plea for<br />

peace (“Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis“), before the<br />

work ends in a ro<strong>und</strong>ed choral so<strong>und</strong>, oscillating between mourning and hope to the<br />

iridescent so<strong>und</strong>s of the carillon.<br />

Morton Feldman composed The Rothko Chapel in 1972 as a tribute to his friend Mark<br />

Rothko, who, like Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman,<br />

Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg and Philip Guston, belonged to the painters of the<br />

New York School, whose abstract expressionism Feldman tried to transfer into his music:<br />

Moments like “All-over” and “Non-relational”, used to describe Pollock‘s paintings, in<br />

which finely spun, calligraphic-looking webs of traces and threads of colour, layered in<br />

many layers, completely cover the canvas without the formation of hierarchies or centres<br />

of vision. The approximately 23-minute piece for percussion, celesta, viola, soprano, alto<br />

and double mixed choir is named after a meditation chapel at the Ménil Fo<strong>und</strong>ation in<br />

Houston, Texas, for which Rothko had made fourteen large-format paintings. Feldman<br />

was inspired by the haunting effect of the paintings and the chapel‘s particular<br />

architecture, with his music permeating the entire space: “My choice of instruments<br />

(in terms of applied force, balance and timbre”, Feldman says, “was influenced by both<br />

the space of the chapel and the paintings. Rothko‘s paintings go to the very edge of the<br />

canvas, and I wanted to achieve the same effect with music - that it should permeate<br />

the whole octagonal space and not be heard from a certain distance. The result is very<br />

similar to what you hear on a record: the so<strong>und</strong> is closer, more physical to you than in a<br />

concert hall. The overall rhythm of the paintings, the way Rothko arranged them, created<br />

an unbroken continuity.” In order to achieve a dramatic expression equal to that of the<br />

paintings, Feldman divided the work into contrasting parts: “Whereas in the paintings

ENGLISH<br />

it was possible to repeat colour and gradation and yet retain dramatic expression, I felt<br />

that the music needed a series of extremely contrasting sections [...]: 1. A rather long<br />

declamatory opening; 2. A more consistent ‚abstract‘ section for choir and bells; 3. A<br />

motivic interlude for soprano, viola and timpani; and 4. A lyrical conclusion for viola with<br />

vibraphone accompaniment, later joined by the choir with a collage effect.”<br />

The motet Spem in alium by Thomas Tallis, the court organist of the Tudors, is considered<br />

the ultimate in vocal polyphony: a fascinating spatial so<strong>und</strong> experiment whose singularity<br />

is only limited by the fact that it seems to have been a direct response to a composition by<br />

the Italian diplomat and composer Alessandro Striggio, who had visited London in 1567<br />

and had a 40-voice motet performed on that occasion. Afterwards, the Duke of Norfolk<br />

publicly asked whether none of our “Englishmen” were capable of writing “so good a<br />

songe”, to which Tallis replied with the setting of Spem in alium - also for forty voices, or<br />

more precisely: for eight five-part choirs, which, in imitation of Venetian polychoralism,<br />

acoustically open up the space that becomes the symbol of the divine cosmos. The Duke<br />

presumably had the work performed in his country house, Nonsuch Palace, which had<br />

an octagonal dining room with four galleries - a room in which Tallis could have ideally<br />

placed his 40 musicians to fully develop the refined so<strong>und</strong> dramaturgy. For the so<strong>und</strong>s<br />

seem to rotate in a spiral (first aro<strong>und</strong> to the right and from “qui irasceris” onwards<br />

aro<strong>und</strong> to the left) and correspond antiphonally with each other: in four groups of two<br />

choirs, in two groups of four choirs as well as in all possible gradations. After this<br />

kaleidoscopic variety of fascinating so<strong>und</strong> and spatial effects, after a brief moment of<br />

silence, all participants provide an imposing dramatic climax that still places the listener<br />

at the centre of the so<strong>und</strong>ing universe.<br />

The Gloria by Jan Sandström is part of the Missa a La Casa de la Madre y el Nino, which<br />

was written for Erik Westberg‘s vocal ensemble between 1992 and 1995. The special<br />

addition in the title is the name of an orphanage in Bogotá where the Swedish composer<br />

adopted an orphan. The idea for the Gloria came to Sandström, as he himself confessed,<br />

in a dream which he described thus: “In a church on a mountain high above Bogotá, a<br />

children‘s choir was continuously repeating the Gloria, while sometimes one, sometimes<br />

the other child stepped out of the crowd with the exclamation ‚Gloria in excelsis‘.” This<br />

alternation between choir and precentor is also fo<strong>und</strong> in the composition - realised<br />

with the help of several soprano and tenor solos, which seem like individual rapturous<br />

angelic voices, complete with echo, and enhance the spatial effect by positioning them<br />

opposite the choir. Sandström, who began his musical career as a chorister and taught<br />

composition as a professor at the Piteå Conservatory from 1989 onwards, wrote with<br />

his Gloria an exhilarating music full of dazzling mixture so<strong>und</strong>s in a catchy harmony<br />

that draws the listener in from all directions. He is considered a leading composer of<br />

Scandinavian choral music, with the 1987 Christmas carol arrangement Es ist ein Ros<br />

entsprungen among his best-known works.

Garth Knox, one of the leading interpreters and composers of contemporary music,<br />

was a member of Pierre Boulez‘s Ensemble <strong>Int</strong>erContemporain and violist in the Arditti<br />

Quartet for many years, which gave him the opportunity to work closely with composers<br />

such as Ligeti, Berio, Xenakis and Cage. With his Quartet for one, he composed a “string<br />

quartet” for solo viola in the Corona lockdown of spring 2020, when all concerts were<br />

cancelled and making music in ensembles was forbidden: “Just as lonely children invent<br />

imaginary playmates to keep themselves company, my own disappointed need to play<br />

with others led me to invent some imaginary colleagues and explore in a light-hearted<br />

way the possibilities of performing chamber music with them.”<br />

The result was a piece “that takes place in the mind of a violist who dreams of giving a<br />

concert with a string quartet in front of a large audience. Although the violist is alone,<br />

he is actually playing a quartet! Each of the four strings of the viola corresponds to an<br />

instrument of the quartet, and as soon as the respective instrument starts, the musician<br />

sits down on its chair and plays on its string (the stage is equipped with four desks and<br />

four chairs). To imitate the fullness of the low cello so<strong>und</strong>, the lowest string of the viola is<br />

tuned down to a.” Knox dedicated the work to violist Lawrence Power, who premiered the<br />

piece on 18 June 2020 at the completely empty Royal Festival Hall in London.<br />

Slovenian composer Nana Forte (born 1981) wrote En ego campana on commission from<br />

the Swedish Radio Choir, which premiered the sonorous piece for two four-part choirs<br />

at Stockholm‘s Engelbrektskyrkan on 12 November 2016. The Latin text set to music<br />

comes from the collection of poems Carmina proverbialia, proverbs or “wisdoms” set to<br />

verse, many of which were set to music by the Slovenian Renaissance composer Jacobus<br />

Gallus. “En ego campana” (No. 45) tells of how the ringing of church bells accompanies<br />

people, with Nana Forte‘s music beginning with simple and repetitive so<strong>und</strong> patterns.<br />

Through changes in rhythm and dynamics, as well as an overlapping of both choirs,<br />

the initially simple bell so<strong>und</strong>s become increasingly complex, also clearly echoing the<br />

different emotions reflected in the text.<br />

Nana Forte completed her composition studies at the Academy of Music in Ljubljana, at<br />

the Hochschule für Musik “Carl Maria von Weber” in Dresden and at the Universität der<br />

Künste in Berlin. She wrote orchestral and chamber music works, pieces for various<br />

solo instruments and choral music - already during her studies she collaborated with<br />

many Slovenian choirs, and some of her choral works were awarded prizes. In 2007<br />

she represented the Republic of Slovenia in the “European Ensemble Academy” project<br />

organised by the German Music Council on the occasion of the German Presidency of<br />

the European Union. Her Libera me for two mixed choirs was a compulsory piece at the<br />

finals of the 5 th <strong>Int</strong>ernational Competition for Young Choir Conductors “Europa Cantat”<br />

in Ljubljana in 2009 and has since been in the repertoire of many European choirs. Her<br />

opera Paradies oder nach Eden (Paradise or After Eden), based on a libretto by Maja<br />

Haderlap (in which Adam and Eve are given a chance to start anew), had its successful<br />

premiere at the Vorarlberger Landestheater in Bregenz on 22 September 2016.

ENGLISH<br />

In contrast, the premiere of György Ligeti‘s Apparitions on 19 June 1960 in Cologne<br />

caused a real scandal - this music was too different from the mainstream of modernism<br />

at the time. For in the orchestral piece, in which the so<strong>und</strong>s flow into each other in a statelike<br />

manner, the composer, who had fled from Hungary, had for the first time realised<br />

his idea of a music in which there are “neither melodies nor chords nor rhythms”. The<br />

same applies to Atmosphères, with which Ligeti had his international breakthrough -<br />

with a fluctuating so<strong>und</strong>-surface composition in which the laws of gravity seem to be<br />

suspended. No wonder star director Stanley Kubrick used the work in his epic space<br />

parable 2001: A Space Odyssey - just like Ligeti‘s Lux Aeterna for sixteen-part choir from<br />

1966, in which the composer succeeded in transferring compositional techniques such<br />

as micropolyphony and cluster harmony, previously tested in his revolutionary orchestral<br />

pieces, to vocal music, whereby the meditative harmonic structures crystallise out of<br />

a fluctuating so<strong>und</strong> field. Moreover, the fluctuating so<strong>und</strong>s suggest an illusionary<br />

depth of space that seems to open up into infinity. Formally, the work consists of three<br />

canons - two eight-part for soprano and alto and for tenor and bass, respectively, and<br />

one four-part for four altos. The caesurae between the sections are marked by a threepart<br />

pianissimo chord on the word “Domine”, so<strong>und</strong>ed in the highest and respectively<br />

lowest register. “When I saw the film,” says Ligeti, “I was thrilled. I feel that my music in<br />

Kubrick‘s selection is ideally suited to these space and speed fantasies that occur in the<br />

film.” However, because Kubrick had used the pieces without the composer‘s knowledge<br />

or permission, there was a messy aftermath. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer declared that it<br />

would extend the advised lawsuit for decades over a dispute value of 30,000 US dollars<br />

and offered Ligeti 1000 dollars as “compensation”. “In the end,” the composer said,<br />

“they paid $3,000.” Yet 2001 was the most financially successful flick of the 1968 film<br />

year, grossing over $190 million in cinemas worldwide.<br />

Harald Hodeige

interkultur.com/wernigerode2023