Geology of Southern California.pdf - Grossmont College

Geology of Southern California.pdf - Grossmont College

Geology of Southern California.pdf - Grossmont College

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

36 <strong>Geology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Southern</strong> <strong>California</strong><br />

<strong>Southern</strong> <strong>California</strong>.9<br />

<strong>Southern</strong> <strong>California</strong> Earthquakes<br />

Earthquakes in <strong>California</strong> are an inevitable consequence <strong>of</strong><br />

the interactions between tectonic plates along the forward<br />

edge <strong>of</strong> a west-moving continent. The forces generated<br />

along the transform boundary between the Pacific and<br />

North American plates result in thousands <strong>of</strong> earthquakes<br />

every year. The ground literally shakes continuously in<br />

<strong>California</strong>, but most <strong>of</strong> these tremors go unfelt by people<br />

and rarely cause damage. Nonetheless, the seismic history<br />

<strong>of</strong> southern <strong>California</strong> includes some devastating events<br />

that serve as reminders <strong>of</strong> the serious hazards facing those<br />

who live near such as active plate boundary.<br />

Historic and Ancient Earthquakes in <strong>Southern</strong><br />

<strong>California</strong>: Though earthquakes occur in many parts <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>California</strong>, exceptionally powerful temblors have repeatedly<br />

shaken the southern part <strong>of</strong> the state. The 1857 Fort Tejon<br />

earthquake and the Lone Pine earthquake <strong>of</strong> 1873 rank<br />

among the greatest seismic events in <strong>California</strong> history.<br />

The Fort Tejon earthquake (estimated magnitude 7.9)<br />

resulted from a sudden slip along more than 300 kilometers<br />

(180 miles) <strong>of</strong> the San Andreas fault from the Transverse<br />

Ranges area to the central Coast Ranges. Effects <strong>of</strong> this<br />

earthquake were widespread and included uprooted trees,<br />

damaged building, and disrupted stream drainages, and<br />

liquefaction. Only the sparse human population at the<br />

time limited the death toll to one. The Lone Pine earthquake<br />

was more tragic. At least 23 people died when the<br />

magnitude 7.8 quake toppled most <strong>of</strong> the adobe brick<br />

buildings the eastern Sierra Nevada town. The Lone Pine<br />

event resulted from slip along the normal fault zone at the<br />

base <strong>of</strong> the Sierra Nevada, and thus occurred in a completely<br />

different plate tectonic setting as the Fort Tejon shock.<br />

The scarp, or surface exposure, <strong>of</strong> this normal fault is still<br />

visible in the hills just west <strong>of</strong> Lone Pine (Figure SC.19).<br />

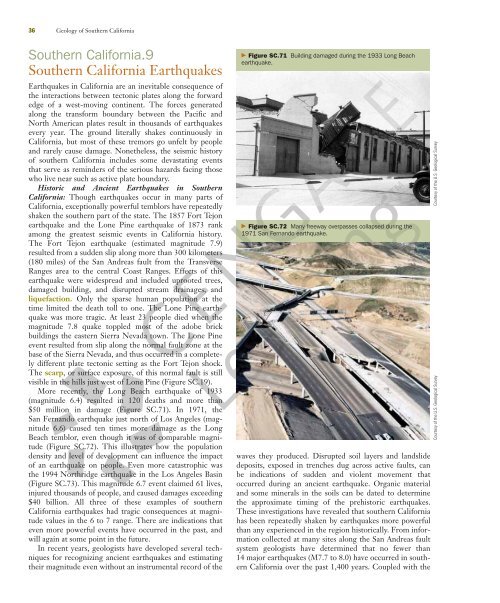

More recently, the Long Beach earthquake <strong>of</strong> 1933<br />

(magnitude 6.4) resulted in 120 deaths and more than<br />

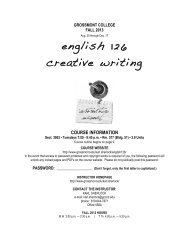

$50 million in damage (Figure SC.71). In 1971, the<br />

San Fernando earthquake just north <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles (magnitude<br />

6.6) caused ten times more damage as the Long<br />

Beach temblor, even though it was <strong>of</strong> comparable magnitude<br />

(Figure SC.72). This illustrates how the population<br />

density and level <strong>of</strong> development can influence the impact<br />

<strong>of</strong> an earthquake on people. Even more catastrophic was<br />

the 1994 Northridge earthquake in the Los Angeles Basin<br />

(Figure SC.73). This magnitude 6.7 event claimed 61 lives,<br />

injured thousands <strong>of</strong> people, and caused damages exceeding<br />

$40 billion. All three <strong>of</strong> these examples <strong>of</strong> southern<br />

<strong>California</strong> earthquakes had tragic consequences at magnitude<br />

values in the 6 to 7 range. There are indications that<br />

even more powerful events have occurred in the past, and<br />

will again at some point in the future.<br />

In recent years, geologists have developed several techniques<br />

for recognizing ancient earthquakes and estimating<br />

their magnitude even without an instrumental record <strong>of</strong> the<br />

� Figure SC.71 Building damaged during the 1933 Long Beach<br />

earthquake.<br />

� Figure SC.72 Many freeway overpasses collapsed during the<br />

1971 San Fernando earthquake.<br />

waves they produced. Disrupted soil layers and landslide<br />

deposits, exposed in trenches dug across active faults, can<br />

be indications <strong>of</strong> sudden and violent movement that<br />

occurred during an ancient earthquake. Organic material<br />

and some minerals in the soils can be dated to determine<br />

the approximate timing <strong>of</strong> the prehistoric earthquakes.<br />

These investigations have revealed that southern <strong>California</strong><br />

has been repeatedly shaken by earthquakes more powerful<br />

than any experienced in the region historically. From information<br />

collected at many sites along the San Andreas fault<br />

system geologists have determined that no fewer than<br />

14 major earthquakes (M7.7 to 8.0) have occurred in southern<br />

<strong>California</strong> over the past 1,400 years. Coupled with the<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> the U.S. Geological Survey<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> the U.S. Geological Survey