Fritz Tröger - Pierre Menard Gallery

Fritz Tröger - Pierre Menard Gallery

Fritz Tröger - Pierre Menard Gallery

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Frit z <strong>Tröger</strong>

Frit z <strong>Tröger</strong><br />

<strong>Pierre</strong> <strong>Menard</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> | 10 Arrow St. | Cambridge, MA 02138<br />

www.pierremenardgallery.com

Published by<br />

<strong>Pierre</strong> <strong>Menard</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

10 Arrow St.<br />

Cambridge, MA 02138<br />

617.868.2033<br />

www.pierremenardgallery.com<br />

© 2007 <strong>Pierre</strong> <strong>Menard</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

All rights reserved<br />

All images © the artist<br />

All text © the author’s<br />

Printed and bound by Apex Book Manufacturing, GA, USA<br />

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner<br />

without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.<br />

Edited by John Wronoski & Heide Hatry<br />

Designed by Erica Mena<br />

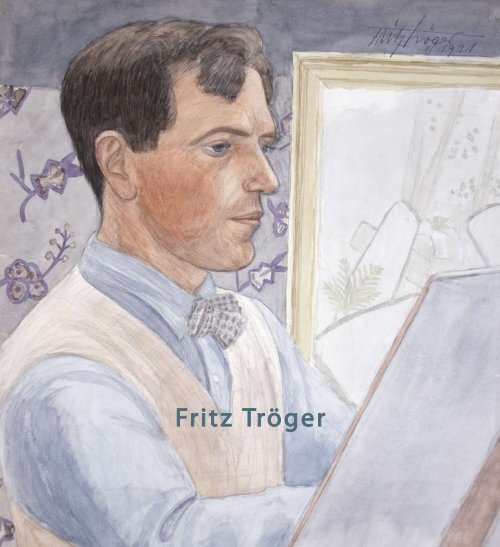

Front Cover image: Maler Georg Siebert / The Painter Georg Siebert<br />

Watercolor and Pencil on Paper<br />

22.25 x 29.75 in / 60 x 80 cm, 1931<br />

Back Cover image: Untitled<br />

Watercolor and Ink on Paper<br />

16 x 23 in / 40 x 60 cm, 1949<br />

With gratitude to Bernhard Stübner.

Contents<br />

1<br />

3<br />

7<br />

10<br />

13<br />

<strong>Fritz</strong> <strong>Tröger</strong><br />

by Heide Hatry & John Wronoski<br />

Im Schutzraum der Innenwelt<br />

by Heinz-Norbert Jocks<br />

In the Bunker of the Inner Life<br />

by Heinz-Norbert Jocks<br />

translated by Laura Hatry & John Wronoski<br />

Biographie <strong>Fritz</strong> <strong>Tröger</strong><br />

Plates

Untitled<br />

Etching<br />

20 x 25.75 in / 50 x 60 cm<br />

Undated

Although <strong>Fritz</strong> <strong>Tröger</strong> disavows style, suggesting he is pursuing something like the discoverable essence<br />

of his subjects, or perhaps even more, what color and line themselves are striving for, or dreaming of, in the<br />

manner of the self-conscious Zettel of Arno Schmidt’s great masterpiece: “I am not drawing what I see, I draw<br />

what I feel when I see something. I’m not interested in a certain style which might attract attention through its<br />

peculiarity, but in a basic formulation about regularity of line and color,” it is what must be termed his style that<br />

is disconcerting about the work, and which imparts to it its preternatural calm, or perhaps rather its emptiness.<br />

And it is this emptiness which makes the work disturbing and compelling.<br />

These figures, who inadvertently depict the ravages of inter-bellum, war-time and post-war Germany, represent<br />

the cannon-fodder, the scathed, the wounded, the shell-shocked, the marginal and the irrelevant left in<br />

the wake of these various displacements. Their souls may not have been lost, but they have retreated to places<br />

beyond hearing, beyond sharing their pain except in the simplest sense of keeping the company of other damaged<br />

men and women. Even in work, there is no communication beyond the coordinated movement which the<br />

task itself requires. If it is calm they exude, it is an ominous and inhuman calm; if it is defeat, it is the defeat of<br />

the walking wounded, of mere survival in lieu of human aspiration.<br />

Information about <strong>Tröger</strong>’s life and aesthetic is scant and not terribly reliable, to judge from the few<br />

exhibition catalogues produced during his lifetime or the biographical data accessible in electronic sources.<br />

One commentator suggested that the strange quite, the resistance to sound, even in the midst of what must<br />

be a clangorous workplace, somehow derives from his deafness. And there is something impossible to ignore<br />

about it once this notion has infiltrated one’s thinking about the work. His subjects invariably exude a sense<br />

of self-containedness or fundamental solitariness, and perhaps even an inability to present themselves in any<br />

other way. To explain this strange phenomenon, which one is anxious to interpret as a statement about, and a<br />

brilliant evocation of, the essential loneliness of human-kind, as the result of the painter’s deafness, which at<br />

worst, was a fleeting, and most likely forgotten, malaise, makes the sort of sense explanations of El Greco’s art<br />

predicated upon his astigmatism do at first hearing: of course his world is different from that of others, and this<br />

is the crux! Indeed, in his youth, <strong>Tröger</strong> did suffer a temporary deafness as the result of scarlet fever, but it is<br />

only by analogy, or maybe by dint of his own intense focus on this perhaps defining experience that his work<br />

has become steeped in silence: he was not, in fact, deaf. It would seem, however, that <strong>Tröger</strong> lived an essentially<br />

solitary, self-contained, and even a sexless life. Is he projecting his own experience onto his subjects, though, or<br />

is he, on account of his experience and sensibility, merely particularly well suited to depict their own essential<br />

voicelessness? And is it that which he wants to equate with an absence of style?<br />

Though they are not uniformly members of the working class, it is the world of the worker with which<br />

<strong>Tröger</strong>’s sensibility resonates, and perhaps the lack of a voice among his subjects is as much a political and social<br />

commentary as it is the result of the horrifying historical facts of their lives. Critics have identified <strong>Tröger</strong><br />

as a “socialist of the heart – for he was far too inert to act on his convictions.” His heroes were Vincent Van<br />

Gogh and Käthe Kollwitz, though he had not the energy to be the former nor the passion to be the latter. He<br />

nevertheless succeeded in portraying an aspect of the humble life which didn’t yet exist when Van Gogh and<br />

1<br />

<strong>Fritz</strong> <strong>Tröger</strong>

Kollwitz were at work, and which he himself, in the earlier work, to some extent pre-figures: the soul of man<br />

under socialism (not excluding the prefatory epochs of horror to which state socialism was an abrupt and imperfect<br />

solution).<br />

In his catalogue essay of 1974, G. Clausnitz accords to <strong>Tröger</strong>’s special perspective a whole category of Neue<br />

Sachlichkeit practice – his is an art of reflection, not one of turbulence, unlike the vast majority of his confreres<br />

in the movement. He is not, like Dix or Grosz, depicting the overt human disaster that was the First World War<br />

and its aftermath, but rather the much subtler inner confusion of the common man in its wake, although his<br />

damaged souls might well represent the darker reality of the damaged bodies which populate Dix’s canvases. It<br />

is probably with that of Christian Schad that his early work has the most in common, though <strong>Tröger</strong>’s avoids<br />

even discrete symbolism or, in fact, commentary of any overt sort, itself a means of enveloping his subjects in<br />

silent isolation.<br />

There is certainly a trajectory in which <strong>Tröger</strong>’s work may be placed, beginning with German Medieval<br />

wooden statuary and the Renaissance woodcut, and including a small swath of German Realism, perhaps most<br />

notably the work of Wilhelm Leibl, and with more or less relevant affinities across the range of the muted version<br />

of Social Realism visited upon German art in the East under the pall of the Soviet era. More recently, it is<br />

difficult not to see the same questions being addressed, though certainly more forcefully, and self-consciously,<br />

in Anselm Kiefer’s empty interiors of the seventies, which are the analogue, and perhaps even the essence of<br />

that which Troeger was ultimately seeking to express. Emptied of human content, but only emptied of human<br />

content, do they possess the spirit of the lost who are <strong>Tröger</strong>’s subject. They are places where the weight of souls<br />

is heavy in the absence of people. And unlike the living, the dead may yet claim souls. Among contemporary<br />

artists, the rough wood sculptures of Stephan Balkenhol deeply, and equally unironically, if in a post-modern<br />

mode, invoke the spirit of <strong>Tröger</strong>, while the whole neo-figurative, “Neue neue Sachlichkeit,” movement, perhaps<br />

epitomized by Christoph Ruckhäberle, may find in <strong>Tröger</strong> an unacknowledged, and unjaded, precursor.<br />

The American Edward Hopper’s work, recently the subject of two major exhibitions, reflects a view of human<br />

life which compares interestingly with <strong>Tröger</strong>’s in its profound depiction of human solitude, but the version<br />

of solipsism advanced in <strong>Tröger</strong>’s portraits, work-scenes and environments is one rather of an experiential<br />

than of existential necessity, and though it is therefore infinitely more horrific, it is also vastly more hopeful.<br />

2<br />

Heide Hatry & John Wronoski<br />

Boston, July 2007

Im Schutzraum der Innenwelt<br />

Angesichts der mit Atmosphäre, hier Tristesse, dort Heiterkeit, aufgeladenen Porträts von <strong>Fritz</strong> <strong>Tröger</strong>, der<br />

1894 in Dresden geboren wurde, spürt man seine aufrichtige Sympathie mit Menschen aus dem Alltag. Ja, eine<br />

tief empfundene Menschlichkeit. Nie legt er die Personen, die er so liebenswert wie mit Herzen skizziert, darauf<br />

fest, was sie sind oder sein wollen. Von seinem Gegenüber macht er sich nämlich weder ein soziologisches<br />

noch ein psychologisches Bild en Detail. Auch betreibt er keine unnötige Heroisierung und erst recht keine<br />

Entlarvung oder Enttarnung. Stattdessen versucht er, ohne aufdringlich zu sein, der Gruppe, dem Einzelnen,<br />

gar Vereinzelten so vorurteilslos wie möglich zu begegnen. Dabei gelingt es ihm auf beiläufige Weise, sein<br />

Gegenüber ein Stück weit in seinem beständigen Wesen zu erfassen. Ja, er kommt an die Menschen außerhalb<br />

oder innerhalb der Gruppe so nah heran, dass wir, dadurch auf sie neugierig geworden, unweigerlich nach ihrer<br />

Identität oder nach ihrer Geschichte fragen.<br />

Wer sind sie? Wie leben sie? Womit sind sie befasst? Woran denken sie? Was bekümmert sie? In welcher<br />

Lage verharren sie? Was würden sie uns wohl erzählen, wenn wir uns zu ihnen an den Tisch setzen würden?<br />

Von der Arbeit, von den Kindern oder von der Frau daheim?<br />

Welchem Milieu sie entstammen, ist auf Anhieb nachvollziehbar. Aus einfachen Verhältnissen kommend,<br />

sehen wir sie in einer Kneipe, am Tisch sitzend, bei der Arbeit oder am Steuer eines Traktors. Neben Bauern<br />

mit Pferden sind auch Kipper beim Entladen ins Bild gerückt. Zudem zwei Männer bei ihrer Unterhaltung auf<br />

einem von Pferden durch die Landschaft gezogenen Wagen. Bemützte Kumpel mit nacktem Oberkörper lassen<br />

sich mal bei der Kohleförderung, mal pausierend beobachten. Und ein beschnäuzter Tischler mit Schürze, an<br />

der Sägemaschine stehend, weckt ebenso die Lust am Zeichnen wie eine kleine Gruppe rastender Waldarbeiter<br />

oder die Kumpel, die ihre Freizeit gemeinsam am Tisch ihrer Baracke verbringen. Ein Lokführer wirkt ebenso<br />

zufrieden wie eine sich gerade ausruhende Brigade. Wenn Gruppen in den Mittelpunkt der Aufmerksamkeit<br />

geraten, so sieht der Zeichner jeden einzelnen mehr als Teil eines Ganzen denn in seiner Isoliertheit. Letztlich<br />

wird eines evident: Der Mann, der da mit Hingabe vor dem Motiv zeichnet, nähert sich seinen „Modellen“<br />

nicht in dem Sinne an, dass er mehr über ihr Inneres erfahren, sie enthäuten oder enttarnen will. Vielmehr geht<br />

es ihm um eine gewisse Nähe, die er sucht, um sie im Akt des Zeichnens zu finden.<br />

Nach außen jedenfalls wirken die Menschen so, als wären sie ganz bei sich, aber mitten in der Welt mit<br />

anderen verankert. Und gleichzeitig erwecken sie den Eindruck, sie wären, vom Künstler mitten im Leben erwischt,<br />

an einem Moment ihres Seins angelangt, wo sich alles zur Geschichte verdichtet. So, dass von dort aus<br />

so etwas wie Überblick möglich ist. Der Lauf der Zeit ist angehalten und dabei eine seltsame Stille eingekehrt.<br />

Der auf Zwischentöne achtende und sie hervorkehrende Maler mit zeichnerischem Auge scheint weniger daran<br />

interessiert zu sein, was die Menschen, die sich ihm zuwenden, in der Zukunft erwartet. Wichtiger ist ihm<br />

deren Erdverbundenheit und Aufgehobenheit in der Gegenwart sowie das Surplus ihrer reichen Vergangenheit.<br />

Deren Einfluss und Spuren reichen offenbar bis ins tagende Jetzt.<br />

Das Merkwürdige ist, dass die Bilder von <strong>Fritz</strong> <strong>Tröger</strong>, obwohl sie gelegentlich nur ein Minimum an<br />

Hinweisen liefern, dennoch ein Maximum an Ausdruckskraft aufweisen. Was erleben wir da? Beispielsweise<br />

3<br />

Ein Versuch zu den Bildern von <strong>Fritz</strong> <strong>Tröger</strong><br />

(Dresden 1894 - Dresden 1978)

einen Mann mit Brille, der auf der Bettkante sitzt. Vor ihm ein Buch, darin er sich vertieft, und hinter ihm eine<br />

hölzerne Tür, die verschlossen ist. Die rechte Hand ruht auf der Matratze des gemachten Bettes und die linke<br />

auf dem Oberschenkel. Die Konzentration dieses Lesers erreicht eine hörbare Lautstärke. Ja, es kommt einem<br />

so vor, als hätte sich der in seiner sensiblen Intellektualität Erfasste in seine Innenwelt wie in ein Schneckenhaus<br />

zurückgezogen. Anwesend in seiner Abwesenheit, die rätseln lässt, hat er sich, wenn auch nur vorübergehend,<br />

von der Außenwelt abgeschottet oder verabschiedet. Er hat sich quasi in Sicherheit gebracht und in den Schutzraum<br />

seiner für uns unzugänglichen Innenwelt begeben.<br />

In einem anderen Porträt dann das Erscheinen eines jungen Mannes mit wallendem Haar. Er trägt eine<br />

Jacke, darunter ein Hemd. Die Umgebung ist ausgeblendet, und unser Blick ganz auf die umrisshaften Linien<br />

konzentriert, die den Kragen betonen. Darüber hinaus stechen die Schatten im Gesicht mit wenigen Falten<br />

hervor. Das markante Kinn passt zur geraden Nase und diese zu den intensiv blickenden Augen. Die Schönheit,<br />

die diesen Mann in den jungen Jahren auszeichnet, ist nun aber keine rein äußere. Von Innen leuchtend,<br />

steht sie in Kontakt zu dem, was geschehen ist. Doch die Erlebnisse, die ihn zu dieser Persönlichkeit haben so<br />

früh reifen lassen, bleiben unerzählt, sind ausgeblendet. Seine Aura bildend, bleibt sie Teil seines Geheimnisses.<br />

Ganz anders die Frau im Liegestuhl. Die Beine übereinandergeschlagen. Der große Kopf seltsam nach vorne<br />

geneigt. Die Hände fest an das hölzerne Gerüst des Stuhles geklammert. Auch sie existiert ganz für sich. Dabei<br />

innerlich auf etwas focussiert, das sich uns ebenfalls entzieht.<br />

Selbst wenn <strong>Tröger</strong> einen Mann mit gefalteten Händen im Liegestuhl eines umzäunten Gartens aus Bäumen<br />

bequem Platz nehmen lässt, so zeugt auch dessen uns so zugewandtes Gesicht trotz seiner relativen Offenheit<br />

von einer gewissen Introvertiertheit oder Zurückhaltung. Dass dieser Herr da so in sich ruht und dabei<br />

eine schiefe Fliege trägt, wirft die Frage auf, ob er gerade von einem Fest oder von einem Konzert nach Hause<br />

gekommen, auf den Sprung oder in Aufbruchstimmung begriffen ist.<br />

Sogar in den Gemälden, in denen Menschen fehlen, nur Bäume, Gebüsch und Wege, Himmel und Erde<br />

zur Darstellung gebracht sind, spiegelt die Menschenleere etwas von der Lehre der inneren Empfindsamkeit des<br />

Künstlers wider. Seine Verletzlichkeit ist eng mit seiner Durchlässigkeit verbunden. Im Grunde nimmt <strong>Tröger</strong><br />

etwas von den Geheimnissen der anderen in sich auf, ohne sie preiszugeben. Er projiziert seine Befindlichkeit,<br />

die er mit den anderen teilt, auf seine Umgebung. Bis zu guter Letzt bleibt er der Vertraute der Porträtierten,<br />

die sich von ihm keineswegs ertappt fühlen.<br />

Alles in allem geht es ihm in seinen Bildern nie um die Ermittlung von Aktualität im Sinne der auf den Augenblick<br />

lauernden Fotografie. Etwas Zeitloses, wenn nicht sogar Ewiges haftet seiner vorbehaltlosen Sicht auf<br />

Menschen an. Seine von einer Schlichtheit, die allem von vornherein das Prätentiöses nimmt, zeugenden Skizzen<br />

wirken wie unromantische Gedichte an die Dauer. Ja, unter seiner Regie erscheinen die Menschen, denen<br />

er als Zeichner ein Gesicht gibt, oft so, als würden sie sich in dem, was sie gerade tun, ganz unbeobachtet fühlen.<br />

<strong>Tröger</strong> ist jedoch alles andere als ein seine Neugierde stillender Voyeur, der sich des Anderen bemächtigt.<br />

Auch kein Eindringling in fremde Welten, zu denen er sich mit Gewalt oder wider dem Willen der anderen<br />

Zugang verschafft. Stattdessen wird er von denen, denen er sich mit Behutsamkeit und großer Achtsamkeit<br />

annähert, als einer der Ihren akzeptiert.<br />

Ja, die Welt der Menschen, die er in ihrem Sosein annimmt sowie erkennt, ist ihm weder fern noch<br />

fremd. Im Grunde ist er ihr emsiger Beschreiber, ein begnadeter dazu. Seine besondere Empfindsamkeit als

Repräsentant seiner Zeit spiegelt sich darin, wie er auf Menschen und Landschaften blickt. Der Respekt, den<br />

er für sein Gegenüber aufbringt, ist so stark, dass da bei aller Nähe, die zwischen ihm und seinem Gegenüber<br />

aufkommt, eine so unhintergehbare wie unüberbrückbare Distanz waltet. Sie ist es, die dem Anderen so etwas<br />

wie Anmut oder Würde verleiht. Er belässt sie so, wie sie sind. Er tastet nichts an. Er hinterfragt auch nichts.<br />

Er ist eben kein Kritiker. Auch kein Jasager. Irgendetwas dazwischen.<br />

Alles in allem widmet er sich den Menschen, deren Gesellschaft er aufsucht, immer erst dann, wenn<br />

zwischen ihnen und ihm genügend Vertrauen aufgebaut ist. Denn dann erst scheint der Moment für ihn<br />

gekommen zu sein, wo er sich ein Bild von ihnen zu machen beginnt. Ihm liegt daran, mit ihnen so etwas wie<br />

eine Alltäglichkeit der Begegnung herzustellen. Und darum passt es auch nicht, in seinem Fall von „Modellen“<br />

zu sprechen. Da ist mehr an Beziehung, nämlich Austausch, Neigung und nicht zuletzt Hinwendung. Dass die<br />

Leute sich von ihm so wenig gestört fühlen, hat mit ihrem Gefühl zu tun, dass sie da jemand nicht nur flüchtig<br />

kennen lernen will. Sie nehmen ihn zwar als einen wahr, der nicht ganz zu ihnen gehört, sich aber auf ihre<br />

Probleme einlässt und ihr Leben mitvollzieht. Aber nicht nur die Menschen sagen ihm etwas, auch die Landschaften,<br />

aus denen sie hervorgegangen sind, und die Arbeitswelt, der sie angehören, finden seine Beachtung.<br />

Darunter: Die Förderanlagen des Braunkohlebaus. Die Diagonalen der Transportbänder. Die Stahlkonstruktionen<br />

der Kräne. Bagger und Fördertürme. Schienengleise. Von Wegen durchzogene Dörfer, sowie umzäunte<br />

Häuser im Schnee.<br />

Ganz deutlich tritt hier hervor, dass das Draußen ihm wichtiger als das Drinnen ist. Ja, dass er, weil er<br />

ein Problem mit dem Drinnensein hat, sich hinaussehnt. Mitten unter die Menschen. In ihre Nähe oder weit<br />

weg von allem. So wundert es auch nicht, dass <strong>Fritz</strong> <strong>Tröger</strong>, viele Jahrzehnte die Lausitz, das Land der Gruben<br />

und Werke, bewohnend, in recht spartanischen Verhältnissen hauste. Sein Oberlausitzer Atelier war alles<br />

andere als anheimelnd, gemütlich eingerichtet oder zum Verweilen einladend. Es scheint, als hätte er sich ein<br />

Zuhause geschaffen, das ihn weder zur Ruhe kommen noch zuhause fühlen ließ. Es drängte ihn aus der Stadt<br />

hinaus in die Landschaft, dorthin, wo er frei atmen, anders, für sich leben konnte. Bereits als Kind war für<br />

ihn der Garten nicht nur eine Fluchtlinie, sondern ein Zwischen- oder Niemandsraum, in dem er viel Zeit mit<br />

Schauen verbrachte. Übrigens unternahm er während seines ganzes Lebens wiederholt Reisen durch Europa,<br />

auch längere und kürzere Wanderungen in der Abgeschiedenheit. Nur während des Zweiten Weltkrieges war<br />

dieser Drang zwangsläufig gekappt. Bei allem Fernweh, das bei ihm immer wieder in Heimweh umschlug, war<br />

ihm die Oberlausitzer Welt im Nordosten von Sachsen mit ihren Wäldern so etwas wie Heimat. Unzweifelbar<br />

war er ein Junge mit vielen Innenausschlägen. Ein Introvertierter, für den das Leben kein leichtes Spiel war.<br />

Auf jeden Fall einer, dessen Wille zur Malerei so mächtig in ihm wogte, dass er sich nie fragte, ob er davon<br />

sein Leben würde bestreiten können. Er musste es tun. An der Kunst führte kein Weg vorbei. Während und<br />

nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg studierte er deshalb zunächst an der Dresdner Kunstgewerbeschule und dann an<br />

der Kunstakademie. Mit nichts in der Tasche brach er im Alter von 30 Jahren zum ersten Mal zu Studien nach<br />

Italien auf und ließ sich danach als freier Künstler in Dresden nieder.<br />

Wenn wir nun versuchen, seinen Stil zu benennen, fällt sein Sonderstatus auf. Letztlich ist er kein Moderner,<br />

sondern jemand, der darauf besteht, so zu zeichnen und zu malen, wie er es gegenüber den Phänomenen<br />

für angemessen hält. Die lineare Festigkeit hat mit Handfestigkeit zu tun. Er möchte, dass alles Hand und<br />

Fuß und nichts etwas Fragiles hat. Im Gegensatz zu seinen Kollegen von der Dresdner Sezession, mit denen

zusammen er gelegentlich ausstellte, war er gewiss kein Verehrer von Cézanne. Er hat auch nichts von der<br />

schönen Leichtigkeit der in Farben badenden Impressionisten. Auch der „Brücke“-Stil etwa eines Ludwig<br />

Kirchner ist nicht ganz das Seinige. Bei ihm ist mehr Schwere im Spiel. Dabei stellt er keinerlei Überlegungen<br />

an, die darauf zielen, wie er einen neuen Stil erfinden oder einen Alten erneuern kann. Er hat eben absolut<br />

kein Talent zum Revolutionär der Formen noch der Farben. Auf dem Gebiet der ästhetischen Innovation ist<br />

er weniger zielstrebig als konventionell in einem durchaus positiven Sinne. Auf eine Präzision bedacht, die<br />

zwar nicht immer gelingt, wohl aber von Neuem versucht wird, ist er zwar kein großer, dafür aber ein kleiner<br />

Meister, der uns das Sehen lehrt.<br />

Heinz-Norbert Jocks<br />

Paris, June 2007

In the Bunker of the Inner Life<br />

In the face of the charged atmosphere of <strong>Fritz</strong> <strong>Tröger</strong>’s portraits – sometimes with sorrow, sometimes with<br />

joy – one feels his profound sympathy with ordinary people, a deeply felt humanity. His figures, so tenderly<br />

depicted, are never compelled to assert their identity, even the identity defined by what they might hope to<br />

become. There is no notion of a sociological or a psychological portrait of his subjects, and certainly no adventitious<br />

attempt to glorify or expose or unmask them. Instead he encounters these individuals and groups<br />

unobtrusively and without prejudgment. In doing so, he quite casually manages to capture something of their<br />

essences. Indeed, he depicts them so intimately, yet purely, that the viewer inevitably becomes curious as to<br />

their identity and personal history. Who are they? How do they live? What sort of things are they engaged in?<br />

What do they think about? Care about? What’s going on at this moment in which we find them before us?<br />

What would they tell us if we could sit down at the table with them – about their work, their children or their<br />

wives back at home?<br />

The milieu from whence they come is instantly clear: their circumstances are humble. We see them in a bar,<br />

sitting at a table; in a factory or at the wheel of a tractor. In the same scene in which peasants work with their<br />

horses, workers are unloading trucks of coal and a pair of men converse in the seat of a wagon being drawn<br />

through the landscape by horses. Coal-miners in hard-hats and naked torsos are depicted working, or relaxing<br />

during a break. A mustached cabinet-maker in his apron is sawing wood. All equally compel <strong>Tröger</strong>’s brush.<br />

When it is a group that he depicts, each individual seems more like a part of the whole than an isolated entity.<br />

One thing becomes evident: the artist isn’t approaching these people as objects of study, whose secrets he wants<br />

to reveal; he is, rather, trying to establish a human rapport with them, to achieve a kind of intimacy with them<br />

through the act of drawing.<br />

Outwardly, <strong>Tröger</strong>’s subjects seem quite self-contained, though still well-anchored in the world of others.<br />

At the same time they give the impression that they have been captured, surprised, at a moment in their lives<br />

in which their entire history is compressed; that from the vantage of this particular moment it is possible to<br />

see the whole thing. The flow of time is stopped, and a strange silence has descended. Attuned to nuance, and<br />

skilled at revealing it, the painter seems less interested in what may yet befall the being who confronts him than<br />

in his solidarity with and security in his own present and the rich surplus of past which has eventuated in this<br />

revelatory moment.<br />

It is remarkable that though they sometimes provide only minimal cues to understanding, <strong>Tröger</strong>’s pictures<br />

display a rich expressiveness. What do we experience in them? Let’s take an example: a man wearing glasses is<br />

sitting on the edge of a bed. He is absorbed in a book; behind him is a closed wooden door. His right hand rests<br />

on the mattress of the fastidiously made bed, the left on his thigh. The concentration of this reader reaches an<br />

audible volume. Captured in his palpable intellectuality, it is as though the reader has retreated into his shell.<br />

He is present in his absence, and the viewer wonders whether it is a permanent or only a temporary state. His<br />

inner life, like all of <strong>Tröger</strong>’s subjects, remains a mystery.<br />

7<br />

A Consideration of the Work of <strong>Fritz</strong> <strong>Tröger</strong><br />

(Dresden 1894 - Dresden 1978)

In another portrait a young man with flowing hair emerges from an indefinite background. He is wearing<br />

a work jacket over his shirt. Our gaze is focused on the emphatic outline of his collar. The shadowing of his face<br />

betokens the presence of some premature wrinkles. His prominent chin and straight nose suit the intensity of<br />

his watchful eyes. The beauty he possessed in youth is no longer simply outward but, emanating from within,<br />

its source is his experience. But the experiences that have aged him, that have made him this person, are left<br />

untold, are suppressed. It remains part of his secret, part of his aura. Quite different but equally unforthcoming<br />

is the woman in the deck chair. Her legs are crossed, her large head inclined strangely forward. Her hands grip<br />

the arms of her wooden chair. She, too, exists completely for herself, focused on something which will always<br />

elude us.<br />

Even in a simple and seemingly straightforward scene, in which <strong>Tröger</strong> depicts a man sitting comfortably<br />

with folded hands in a deck chair, surrounded by an enclosed garden, his face, though turned toward the viewer<br />

in a disposition of apparent openness, attests to a certain introversion or reservation. The man sitting there<br />

calmly with his crooked bow tie raises the question of whether he just came back from a party or a concert, or<br />

is about to depart for the evening, perhaps slightly reluctantly.<br />

Even in paintings in which there are no people portrayed at all, but only trees, copses, dirt paths, sky and<br />

earth, the lack of human presence reflects something of the artist’s view of the inner life. His extreme sensitivity<br />

to the essence, as it were, of others, is tied to a kind of permeability, an ability to assimilate, and suggest, something<br />

of the secrets of his subjects without exactly revealing them. He projects these feelings that have become<br />

mutual between himself and his subjects onto even the environments he depicts. To the very end, he remains<br />

the confidant of his subjects, who never feel in any way that they have been stalked or trapped.<br />

<strong>Tröger</strong>’s art is not a matter of capturing “perfect moments” in the way of a photographer lying in wait for<br />

his prey. There is something timeless, if not exactly eternal, inherent in his completely unprejudiced disposition<br />

toward his subjects. His drawings, in their almost monastic simplicity, in which no notion of pretense abides,<br />

seem like unromantic poems on eternity. Under his direction the people to whom he the artist is giving a face<br />

often appear as if they felt totally unobserved in what they are doing. But <strong>Tröger</strong> is the absolute opposite of<br />

a voyeur satisfying his curiosity, wanting to possess the object even if only visually. Nor is he an interloper in<br />

an alien world, into which he’s bullied his way or entered against the will of others. Instead he approaches his<br />

subjects with care and respect and is accepted as one of them.<br />

Indeed, the human world, which he sees and accepts as it is, is neither remote nor alien for him. He is,<br />

fundamentally, its diligent and gifted recorder. As a representative of his time, his special sensibility is reflected<br />

in the way he looks at people and landscapes. The respect he quite naturally accords his subjects is so strong,<br />

that no matter how closely he approaches, there will always be an irreconcilable and insurmountable distance<br />

between them. And it is this which confers something like grace or dignity upon his subjects. He leaves them<br />

the way they are. He doesn’t touch anything. Nor try to get to the bottom of things. He is neither a critic nor<br />

a yes-man, but something in between.<br />

All in all, he dedicates himself as artist to the people whose company he seeks out only when sufficient<br />

trust has been established between him and them, for only then does the moment seem to have arisen for<br />

him in which he can begin to create an image. He is anxious to establish a certain everyday character to their<br />

encounters, on account of which it makes no sense to speak of his subjects as “models.” There is more to their<br />

8

elationship, a mutuality, an affection and, not least, a devotion. That people seem so little disturbed by his<br />

presence has to do with their feeling that they aren’t just making a casual acquaintance. Of course they perceive<br />

him as someone who doesn’t quite completely belong, but still as someone who also contends with the same<br />

problems they do and who understands them fully. And not just the people speak to his particular sensibility,<br />

but even the landscapes they have vacated of an evening and the trappings of the world of labor in which they<br />

dwell – the coal conveyors, the cranes, earth-moving machines, electric towers, lonely rails, villages reticulated<br />

with narrow paths and little houses ringed by fences in the snow.<br />

And here it becomes quite clear that for <strong>Tröger</strong> the outside is more important than the inside. He longs for<br />

the outer world because he is uneasy with the inner one, whether he is among men, near them, or far away from<br />

everything and everyone. It’s not surprising that <strong>Tröger</strong> lived for many years in Lausitz, the land of coal-mines<br />

and factories, and in rather Spartan circumstances. His studio in Oberlausitz was the just opposite of homey<br />

and cozily furnished, nor did it encourage guests to linger. It was as if he made himself a home that was not<br />

a home, which offered no comfort or repose, a home that forced him out of the city and into the countryside,<br />

where, at last, he could breathe freely and live for himself. Even as a child he would escape to the garden as to<br />

a remote horizon, a no-man’s land where he could simply observe and wait. Throughout his life he would travel<br />

around Europe, longer or shorter excursions into his isolation, with the exception of the years of the Second<br />

World War when this became impossible. As his wanderlust would again resolve into homesickness, he saw<br />

the world of the Oberlausitz in northeastern Saxony with its familiar forests as something like a homeland.<br />

Undoubtedly a sensitive child, an introvert for whom life was never easy, and definitely someone in whom the<br />

desire to paint was so intense that he never considered whether he could make a living at it, but engaged the<br />

practice out of simple necessity. During and after the First World War he studied art, first at the Dresdner<br />

Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Fine and Applied Arts) and afterwards at the Kunstakademie (Academy of<br />

Art). At the age of thirty, without a cent to his name, he went to Italy for the first time to draw, and upon his<br />

return settled in Dresden to work as an artist.<br />

If we try to identify <strong>Tröger</strong>’s style, his special status becomes apparent. He isn’t, ultimately, a modern, but<br />

someone who simply insists on drawing and painting in the way he believes is appropriate to the phenomena<br />

at hand. His straightforwardness is an analogue of his view of reality: he wants everything to make sense, and<br />

nothing to remain unclear. Unlike his colleagues of the Dresdner Secession, with whom he occasionally exhibited,<br />

he was no admirer of Cezanne. And he drew nothing from the lightness of the color-besotted Impressionists.<br />

Nor was the Bridge (Brücke) aspect of his style at all that of a Ludwig Kirchner – in his case there is a<br />

fundamental inclination toward gravity. He had no notion of creating a new style nor of renewing an old one.<br />

His talent is not as a revolutionary of form or color. He is scarcely compelled by aesthetic innovation, but is<br />

conventional by preference in a, by all means, positive sense – it is a kind of precision, a being true to the thing<br />

itself that motivates him. Not a great master, therefore, but a lesser one, who teaches us a way of seeing.<br />

Heinz-Norbert Jocks<br />

Paris, June 2007<br />

translated by Laura Hatry & John Wronoski

Biographie <strong>Fritz</strong> <strong>Tröger</strong><br />

19. 05. 1894 In Dresden als Sohn des Zeugfeldwebels Richard <strong>Tröger</strong> geboren.<br />

1900–1905 Bürgerschule<br />

1905–1911 Städtische Realschule, Reifeprüfung.<br />

1911–1915 Deutsche Fachschule für das Schneidergewerbe und Volontäir in verschiedenen<br />

Schneiderbetrieben.<br />

1915–1918 Studium an der königlichen Kunstgewerbeschule Dresden bei Prof. Margarete Junge<br />

und Paul Roeßler – 1918 dort Auszeichnung mit der Silbernen Preismünze.<br />

1918–1920 Tätigkeit als Kostümbeirat am Hof- und Landestheater Meiningen.<br />

1918–1925 Studium an der Kunstakademie Dresden bei Prof. Max Feldbauer, Otto Hettner und<br />

Otto Gußmann.<br />

seit 1925 Freischaffender Maler in Dresden.<br />

1928–1930 Lehrer für Modezeichnen an der Dresdner Kunstschule von Guido Richter.<br />

1929–1933 Studienreisen nach Italien, Spanien, Portugal, Tschechoslowakei, Österreich und<br />

Frankreich.<br />

seit 1925 Versuche mit Malerei auf keramischen Platten in der Meißner Manufaktur<br />

Teichmann – einige Wandbilder entstehen.<br />

1929–1935 Lehrer an der Heeres-Handwerkerschule in Dresden fuer Freihandzeichnen und<br />

Farbenlehre.<br />

bis 1933 Mit Bernhard Kretzschmar, Edmund Kesting, Wilhelm Lachnit und Erich Fraaß<br />

Wortführer für eine engagierte Kunst im “Dienst des Lebens und der Menschheit” in<br />

der Dresdner Sezession.<br />

1932 Mitglied der Dresdner Sezession.<br />

seit 1936 Landatelier in Laske bei Kamenz.<br />

seit 1943 Ausstellungsverbot, Behinderungen durch die “Reichskulturkammer.”<br />

seit 1947 Mitglied des Dresdner Künstlerkollektivs “Das Ufer.”<br />

seit 1949 Regelmäßige Studienaufenthalte in der MTS Barnitz bei Meißen.<br />

10

seit 1951 Arbeitsaufenthalte im VEB Braunkohlenwerk “John Schehr” in Laubusch, enge<br />

Kontakte mit den Bergleuten.<br />

seit 1952 Leiter des Zirkels für künstlerisches Volksschaffen im Kulturhaus “John Schehr,”<br />

Laubusch.<br />

seit 1961 Werksvertrag mit dem VEB Braunkohlenwerk “John Schehr” Laubusch.<br />

1955, 1961 Studienreisen nach Paris.<br />

05. 04. 1978 in Dresden verstorben.<br />

auszeichnungen (honors)<br />

1959 Grafikpreis vom Rat des Bezirkes Cottbus<br />

1962 Martin-Andersen-Nexö-Kunstpreis der Stadt Dresden<br />

1973 Verdienstmedaille der DDR<br />

1974 Vaterländischer Verdienstorden in Silber<br />

1977 Banner der Arbeit, II. Stufe<br />

ausstellungen (exhibitions)<br />

1966 Kleine Galerie im VEB Verlag der Kunst Berlin, VEH Moderne Kunst.<br />

1965, 1974 Dresden, Zwinger, Glockenspielpavillon.<br />

1969 Zwickau, Städtisches Museum.<br />

1974, ‘75, ‘79 Dresden, “Kunst der Zeit.”<br />

1974, 1977 Dresden, Albertinum.<br />

11

1975 Altenburg, Rostock, Frankfurt, Karl-Marx-Stadt.<br />

1976 Laubusch, Bautzen, Görlitz, Kamenz, Luckau, Hoyerswerda, Senftenberg, Halle,<br />

Zittau, Knappenrode.<br />

1996 Sonderausstellung zur Erinnerung an den Dresdner Maler und die Lausitz im<br />

Heimatmuseum Dohna.<br />

Einen großen Teil seines Nachlasses erhielt das Kulturhaus Laubusch. Die Galerie<br />

Neue Meister in Dresden hat einige Arbeiten.<br />

1997 Sonderausstellung “Das Ufer” in der SLUB, (Saechsische Landes und<br />

Universitaetsbibliothek Dresden)<br />

2002 Stadtmuseum Dresden: Faszination Alltag<br />

12

Serviererin / Waitress<br />

Watercolor and Charcoal on Paper<br />

28 x 20 in / 71.1 x 50.8 cm<br />

1957<br />

13

Der Maler / The Painter<br />

Watercolor on Paper<br />

30 x 22.25 in / 80 x 60 cm<br />

Undated<br />

1

Schlafender / Sleeper<br />

Watercolor and Pencil on Paper<br />

25.5 x 19.25 in / 70 x 50 cm<br />

1926<br />

1

Künstlerin / Female Artist<br />

Watercolor and Pencil on Paper<br />

25.6 x 19.7 in / 60 x 50 cm<br />

1927<br />

1

Untitled<br />

Watercolor and Pastel on Paper<br />

25.5 x 19.75 in / 70 x 50 cm<br />

1928<br />

17

Frau im Liegestuhl / Woman in Deck Chair<br />

Watercolor and Pastel on Paper<br />

19.5 x 26 in / 50 x 70 cm<br />

1929<br />

18

Dame mit blauer Halskette im Freien / Lady with Blue Necklace Outdoors<br />

Watercolor and Pencil on Paper<br />

28 x 19.75 in / 70 x 50 cm<br />

1930<br />

1

Untitled<br />

Watercolor and Ink on Paper<br />

19 x 26 in / 50 x 70 cm<br />

1931<br />

20

Untitled<br />

Pastel on Paper<br />

16 x 22.25 in / 40 x 60 cm<br />

1938<br />

21

Untitled<br />

Watercolor and Ink on Paper<br />

15.25 x 22.25 in / 40 x 60<br />

1949<br />

22

Bergmann / Miner<br />

Watercolor and Charcoal<br />

16.5 x 24 in / 40 x 60 cm<br />

1954<br />

23

Der Maler Horst Saupe / The Painter Horst Saupe<br />

Watercolor and Pencil on Paper<br />

20.5 x 29.1 in / 50 x 70 cm<br />

1958<br />

2

Bergmann Paul Schierack / Portrait of Miner Paul Schierack<br />

Watercolor and Ink on Paper<br />

26.4 x 17.7 in / 70 x 50 cm<br />

1958<br />

2

Junger Bauer / Young Peasant<br />

Watercolor and Charcoal on Paper<br />

23.2 x 16.1 in / 60 x 40 cm<br />

1958<br />

2

Untitled<br />

Watercolor and Pastel on Paper<br />

19.75 x 27.75 x 50 x 70 cm<br />

1961<br />

27

Untitled<br />

Watercolor and Pastel on Paper<br />

19.5 x 28.5 in / 50 x 70 cm<br />

1962<br />

28

pierre menard gallery 10 arrow st. cambridge, ma 02138 www.pierremenardgallery.com