Fault Lines - John Knoop

Fault Lines - John Knoop

Fault Lines - John Knoop

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

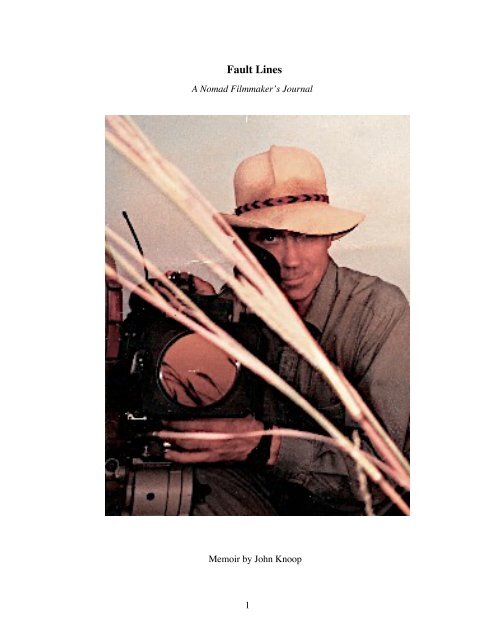

<strong>Fault</strong> <strong>Lines</strong><br />

A Nomad Filmmaker’s Journal<br />

Memoir by <strong>John</strong> <strong>Knoop</strong><br />

1

<strong>Fault</strong> <strong>Lines</strong><br />

A Nomad Filmmaker’s Journal<br />

Copyright 2012 <strong>John</strong> <strong>Knoop</strong><br />

2

I’m on the home stretch. Ready for the Reaper, though not expecting him just yet.<br />

Still eager to savor the human comedy along with memories of many great adventures. I’ve<br />

been sitting here looking out at the San Francisco Bay from my place on the ridge-top in El<br />

Cerrito, trying to figure out how to tell my story. I’ve had a full life and the trade-off is that I<br />

must live in a wreaked body that wakes me at dawn every day with waves of spasms and<br />

soreness. I know I’m lucky that I still have a body that walks and a story to tell. Maybe the<br />

challenge will prevent me from mourning over the decay of our republic and keep my mind<br />

moving even if my body can’t follow at its old pace. There may not be a publisher ready to<br />

take a chance on an oddly structured memoir by a non-celebrity but I hope to publish mine<br />

so I can give copies to my grandchildren. First I must write it.<br />

I hobble into the kitchen and heat some water in a battered saucepan to pour<br />

over a spoonful of Turkish grind. I’ve been making coffee this way since living in Bali<br />

years ago while I shot a film there. Maybe a toke of hash to open the memory bin, which<br />

contains a kaleidoscope of events from both war and peace. Since I have the best bad<br />

luck of anyone I know, there are some narrow escapes in the plot line.<br />

I moved over here to escape the dot-com boom surrounding my former South-of-<br />

Market loft in San Francisco. It’s a small one-bedroom house that I’ve filled with my<br />

books and film equipment. There’s a stone fireplace in the main room. My bed is<br />

wedged between it and a big window that has the Golden Gate in the middle with<br />

Alcatraz gleaming to the left like a floating medieval castle in the morning light. I’ve<br />

torn out a wall, removed the wall-to-wall carpet and asked my brother Rudy to lay down<br />

a pine plank floor so I could turn both rooms into a live/work space, like a small loft. A<br />

tattered Navaho blanket hangs on the wall behind the bed and there’s a Zapateca<br />

weaving I brought back from Oaxaca lying on the bed. A steamer trunk with my<br />

grandfather’s initials carved into the lid is against one wall. He probably packed it when<br />

3

he came to San Francisco in 1906 as a young engineer to help rebuild the city after the<br />

big quake. There’s a DVD duplicating machine sitting on top. Lighting stands and a<br />

square Halliburton case on the floor next to the fireplace. Cobwebs in the corners.<br />

Books, DVD and VHS copies of films on every shelf and surface. It’s a mess, but it’s<br />

mine and I know where to find everything. The kitchen is dirty but I can’t be bothered<br />

with keeping it clean. It hasn’t made me sick. Outside there’s an unkempt herringbone<br />

brick terrace under a white Acacia next to a Monterey pine.<br />

In the second room I weave my way through a disorderly pile of lights, an SQN<br />

mixer, a 16mm Éclair camera and a collapsed Vinton tripod to a drawer stuffed with a<br />

dozen battered notebooks and leather bound journals I started writing in my teens. I’ve<br />

hung on to them for years to prove to myself that I’m a writer as well as a filmmaker.<br />

They have sustained me through more than one identity crisis, and now I’m going to see<br />

if I can use them as a skeleton to hang my story on. The journals will serve as ribs and I’ll<br />

see if I can flesh out the parts between with some of my thoughts now, sitting here in El<br />

Cerrito. Maybe I’ll start with some fairly involved journals I wrote about a motorcycle<br />

trip to Argentina, when I decided to drop out and dive into a serious effort to be a writer,<br />

after a strange freshman year at Columbia College.<br />

Moving to my computer I crack open a musty folder to begin reading the journal I<br />

started writing after I left New York and headed for Argentina.<br />

Paoli, Indiana, June 27, 1958<br />

Thank god, we’re on the road at last. Our BMW R-69 is parked outside a Main Street<br />

café, leaning against the curb, resting on the crash bar that protects its two horizontally opposed<br />

cylinders. It’s a bizarre looking load: a surplus duffel bag on each<br />

side of the rear wheel and another on the rear luggage carrier with a<br />

spare tire draped around it. People slow down to stare as they pass.<br />

There are three boys circling it right now with their chins out,<br />

pointing at the engine. Who knows? It could be the first of its kind<br />

ever seen in these parts. It’s not a Harley or an Indian, so what is it?<br />

Naren Bali and I are having a sandwich. This is the first entry<br />

4

in my “Concise Rambling Journal.” I’m developing my own version of shorthand, using<br />

keywords and initials so I can jot ideas fast. Sitting with us at the counter are four bib-<br />

overhauled farmers talking about anhydrous ammonia prices and their corn crops. Down at the<br />

end of the room there’s a plump woman in a wicker chair facing the window. Her body is<br />

shaking with soundless laughter. One of the farmers turns and asks where we’re going on that<br />

machine, nodding at our bike.<br />

“California,’ Naren says. “And after that, we’re headed to Argentina.”<br />

“That’s quite a trip.” The man whistles, “So far away I’m not sure where it is.”<br />

“Bottom of South America,” his friend says.<br />

Naren is from Buenos Aires. He’s a physics major. He’s been studying and working recently at<br />

Columbia as a computer programmer and now he’s going home and I’m going with him. We left<br />

New York three days ago and pulled away from my parent’s farm east of Cincinnati this morning,<br />

after a heartwarming send off. Who knows where we’ll be tonight. Sleeping next to a wheat field in<br />

Kansas I hope.<br />

It was at the beginning of my freshman year at Columbia College that I showed the bursar<br />

a bogus letter from my uncle saying I was living with them so I could move off campus. That’s<br />

when I met Naren in the funky kitchen of a jazz musician’s apartment on 116 th street where I<br />

rented a room. I noticed a slight accent and his wry sense of humor. He wears a short beard and<br />

has the look of a smart pirate. Soon we were cooking what we called ‘tuna fish shit’: rice and<br />

canned tuna with some frozen beans or peas thrown in for color. There was nothing but<br />

expensive bistro style food in our neighborhood, so we formed a cooking pact to save money and<br />

just ate sandwiches, eggs and things like the tuna slop. It resulted in getting to know each other<br />

and hatching this escape plan. My latest; I’ve actually been trying to escape all my life. Escape<br />

what? Authority and myself. I remember listening to a program on WQXR that played a lot of<br />

music from the Andes. I wanted to see where it comes from. Mostly, though, I was eager to break<br />

free of the academic world to see if I could make it as a writer.<br />

Naren’s been talking to the farmers but he’s tired of waiting for me to finish<br />

scribbling. Time to pay the waitress and bid the farmers good afternoon. Once this steno<br />

notebook goes to the inside pocket of my leather jacket I’m ready to hit the road. It’s my turn to<br />

drive.<br />

5

Colorado, June 30<br />

We alternate the driving, switching every hour or so. There are only a few positions you<br />

can sit in with two on a cycle, although when I’m the passenger I’m working out a way to stretch<br />

by leaning back against the load and raising one knee and then the other to cup it between my<br />

hands. The cycle is running beautifully, even with the load and windage of the three duffel bags.<br />

Coming down quiet two-lane highways at high speed, we are a forbidding sight, especially<br />

with Naren at the helm. He wears a surplus aircraft-carrier flagman’s cap, which resembles an<br />

executioner’s hood. His fierce beard merges with huge, bug-like goggles. Dogs rise from peaceful<br />

repose in clipped yards to howl in amazement and flee tail tight under porches. Children playing<br />

happy games look up smiling to see us approaching and are transfixed by stark terror.<br />

We ride until we’re cold. About forty miles past St Louis we run the cycle off the road,<br />

through a little creek and up a hill in the moonlight overlooking highway 40. I fell asleep talking<br />

to the big dipper. We dozed a couple of hours past sunrise.<br />

Taking a break next to a stream somewhere in the Rockies. Naren’s gone for a walk and<br />

the R-69’s engine is cooling so it’ll be ready for the next climb on this 90 degree afternoon. I<br />

have no idea what form this journal should take. I doubt I’ll have much control over it. It will<br />

probably become an amorphous mass of incoherent outbursts, a sort of interior mumblelogue.<br />

Better that than a travelogue. I’ll send these notes to Judy for safekeeping as I finish each steno<br />

book. Wonder if Judy’s mom will ever accept me.<br />

I called Judy in Cincinnati yesterday morning, asked her mom if Judy was there and heard her<br />

grim response that she wasn’t. Reminded me of our graduation ceremony, when I traded places<br />

with my friend Marvin Freidenn so that the ruse I cooked up to date Judy could continue. Her<br />

family are orthodox Jews and she is forbidden to go out with gentiles, so I dated her all winter and<br />

spring as Marv. She’s a classic beauty, with long black hair and a figure that takes everyone’s<br />

breath away. Judy’s father, who died when she was nine, ran a plumbing and heating business<br />

from a small shop in the impoverished West End district of Cincinnati. He was a prankster, who<br />

liked to gamble and loved taking Judy with him to poker games. They lived in a mostly gentile<br />

neighborhood and once when she was not invited to her best friend’s birthday party because she<br />

was Jewish, Judy gathered some grasshoppers and wrapped them in a little box with a ribbon,<br />

delivered them to the girl’s mom, then ran home to hide in the back yard. The mother was<br />

outraged and stormed down the street where she found Judy’s father sitting on their porch. When<br />

6

she told him what Judy had done and called her a juvenile delinquent he laughed and said he was<br />

proud of her for having the spunk to return an insult.<br />

Judy’s a good student and headed for medical school, very<br />

alert and witty about the way the world works. She and I are sure we<br />

deserve each other, regardless of orthodox traditions. I could tell<br />

that her mother was suspicious whenever I picked Judy up, but we<br />

got away with it, and the graduation gave me an opportunity to seal<br />

the arrangement in public and confound those in the know with what<br />

seemed a meaningless prank. The vice principal, Mr. Leudeke, was<br />

startled when I walked to the stage for Marv's diploma, but he<br />

handed it to me without pause. When my name was called and Marv<br />

walked up, there were some titters in the bleachers.<br />

A wheat field in Kansas the second night. We pulled off a few miles short of Colby, rode a<br />

couple of hundred feet into the end of a 1000-acre field to bed down. A beautiful stand of Duram,<br />

ready to harvest. I’m awake just as the heads of grain catch fire in the rising sun. The color of the<br />

crop gives my gut a tumble; I sit there shivering in the beauty of it, sucking in the pure odor and<br />

tasting the color of the wheat. I see a combine moving in the distance so I wake Naren and tell<br />

him he is about to be thrashed for violating the grain’s virginity. We load up and hit the road.<br />

The people of Kansas have their hearts full of trees and a river flowing through the back<br />

of their minds. The piercing loneliness of a wheat field stretching as far as you can see. Quivering<br />

and undulating in the wind like a well-made body asleep. A dog howling on a low hill as precise<br />

and lonely as pain. Last night at 12,000 feet on the west side of Gore Mountain pass where the<br />

mosquitoes wrote obscenities in stings across my forehead. Earlier we coasted through a canyon<br />

next to a river full of moon. Now it’s on to Utah.<br />

Utah, July 1<br />

We’re at the counter of a brand new, air-conditioned diner on the sweltering floor of a<br />

desolate, empty valley in the Utah desert. There is no other sign of life for miles in any direction<br />

and only one pickup in the huge parking lot. Maybe they’re expecting a uranium rush. Strange<br />

and futuristic as the setting is, there’s something archetypical about an old cowboy sitting at the<br />

counter with us. He looks up when we come in, nods, sweeps his eyes over us, noticing the laden<br />

cycle leaning again the curb outside, and then goes back to mopping his bread through the gravy<br />

pool in his mashed potatoes. His face is bronzed and leathery, with a fine fluff of three day white<br />

7

eard. He wears riding boots, jeans, and a blue work shirt from the pocket of which dangles the<br />

yellow string and paper pull disk of a Bull Durham bag.<br />

After we order he turns to us and says, "You fellers sure picked a hot one. Where you<br />

coming from on that machine?" We tell him and he gives a long low whistle, pushes back his<br />

plate and rolls himself a cigarette with clean rapid movements of his nut-brittle fingers. Then he<br />

tells us the story of a kid he knew who used to herd cows with a motorcycle until one day he was<br />

fooling around in a corral full of horses, "spinning around on the bike and raising dust with the<br />

horses all bunched together over in one corner of the corral, nervous and jumpy as mustangs<br />

holed up in a box canyon. Then the kid comes a little too close and a big gray stallion plants both<br />

his rear hooves up to the hocks right on the engine of that thing. It knocks the kid off and he<br />

crawls away and watches the stallion spin around to raise up on his hind legs and come down<br />

like a hammer on that machine 'til it’s all smashed to hell. Damnedest thing I ever saw."<br />

A cautionary tale from the frontier of the machine age.<br />

I am overwhelmed by what has haunted so many, from De Tocqueville to Thomas Wolfe.<br />

The terrifying vastness of America. That aspect of the country seems incorruptible. Where’s our<br />

famous progress here in the sagebrush? I thought rain and civilization followed the plow.<br />

Berkeley, July 3<br />

We average between 35 and 45 miles per gallon cruising at 70 or 80. From Ohio to<br />

California we spent thirty-six dollars for gas, oil and food with tips. The wind is an almost<br />

constant force against us after Missouri. A pure headwind is best. A quartering wind means<br />

leaning into it, bracing against it, which is a physical effort. Going across the Utah salt flats we<br />

had such a fierce cross-wind that to breathe we had to turn our heads away from it and I could<br />

only get 80 mph out of the bike at full throttle. I checked it the next night in Nevada on a windless<br />

stretch and got 105 mph.<br />

Down the long slope to Sacramento yesterday afternoon. Alfalfa as far as the irrigating<br />

eye can see. Visions of a thousand toiling wagons loaded with green-cured hay merging with the<br />

horizon on their way to the feedlots. San Francisco Bay is red with the blood of the dying sun, as<br />

rocking horse happy, we ride into Berkeley. We’re staying with a former classmate of Naren’s<br />

near the UC campus. Today I’m in San Francisco to check City Lights bookshop, then to hang<br />

out at one of the cafes on Grant Avenue in North Beach. The scene reminds me of the Village, but<br />

I don’t connect with anybody. I’m sending Judy a postcard of Sausalito Harbor and asking her if<br />

she would consider living there with me some time. I think I may be a total romantic. It’s<br />

8

wondrous and frightening how completely one’s mind and body can be possessed by the image of<br />

another person.<br />

Redlands, California. July 7<br />

Miller is right. Rexroth is right. The West Coast, especially along the Pacific to the south<br />

of Big Sur, feels like a bit of paradise. Highway 1 is visual ecstasy. You can live on the beach for<br />

months of the year. I’m tempted to find and knock on Henry Miller’s door, but we decide to keep<br />

going.<br />

Mumbo jumbo of electrical problems as we try to leave L.A. The voltage regulator or the<br />

generator brushes. Find a sandy field along the San Gabriel River and bed down. Sleeping with<br />

one ear to the ground I hear dull thudding; it’s a lone man crossing the field at two in the<br />

morning. At dawn raucous boys are riding their horses through the fog on the other side of the<br />

river. A man is shoveling sand into a bucket and dumping it into the back of his station wagon.<br />

Back in town we get the bike checked out and buy the new battery they say it needs at Milne<br />

Bros, the BMW dealer here. Then we head south, planning to drive the hot country to the<br />

Mexican border at night. The engine is doing fine till it blows its right piston. We limp into a gas<br />

station on the edge of Redlands, make friends with the nice old geezer from Petoskey, Michigan<br />

who owns it, and go to work pulling the head. We camp out in a field across the road and the next<br />

morning I stand by the roadside with my thumb out and my notebook in my pocket so I can write<br />

when I have a chance. I hitch back to Milne Bros. in L.A. for a new piston.<br />

I remember hearing from my parents how eager they were to move back to Ohio at the<br />

end of the war because they hated L.A. so much. Now I see why as I deal with the freeway culture<br />

and the cool indifference people treat each other with. An intriguing mystery: man the blunderer,<br />

the half crazed wanderer, man the hobbled and defeated, the contented inhabiter of suburban<br />

corrals. Anesthetized beyond any knowledge of why his greatest happiness lies in domestication.<br />

No yardstick to measure ease against freedom. It all looks like one long squat on the jakes of<br />

complacency.<br />

I’ve never been to Levittown, but I think I’m surrounded by a western version of it here.<br />

Not where I want to live, ever. Glad the parents were such upper crust snobs about L.A. and took<br />

us back to the farm so I could grow up running through the woods instead of around a sub-<br />

division in Pasadena. I heard the story of how they started the goat caper many times. It went like<br />

this: on their honeymoon, driving south from Cincinnati through Kentucky to the Smoky<br />

Mountains, they stopped to watch a pair of Nubian goats gamboling in a pasture along the<br />

9

highway. Ten days later, on the way home, they stopped again<br />

and bought a young doe. Back on their farm above the Ohio<br />

River, twenty miles east of Cincinnati, they realized that the<br />

goat was not happy. It must be lonely, they decided, and the<br />

solution was to go and get another, a young buck. So my<br />

mother started her herd and her family at the same time.<br />

Within a couple of years, she had a daughter and the first of<br />

five sons and a small herd of Nubians. In 1939 her doe, named<br />

‘Midnight’, set the world record for milk and butterfat<br />

production. I heard about this triumph often enough to know<br />

how proud she was of it and to realize how much it shaped her life. There must have been times<br />

when she chose whether to comfort a crying baby or help a doe give birth to its kid. And times<br />

when she wondered if she’s ever get back to her dream of being a writer. My father built her a<br />

small brick goat barn below the springhouse. It had a hayloft, a set of wooden stanchions and a<br />

milking stand that folded down from the door, all designed and carefully crafted by my father<br />

from finished pine. The goats were given several acres of pasture on which to roam and feed. It<br />

was my task by the time I was seven to milk the six or eight does before school each morning and<br />

again each evening.<br />

She was teaching first grade at Lotspeich, a private school in Cincinnati, when she met my<br />

father. One of my aunts told me they all understood why she fell for him: ‘He was better looking<br />

than Cary Grant, more interesting than her other suitors and he loved Mozart and played the<br />

flute, which won daddy over right away’.<br />

Marrying a talented, handsome, but socially<br />

undistinguished man like my father and living in the country was an<br />

act of rebellion that was not without its price. My grandmother never<br />

approved of her youngest daughter’s marriage or lifestyle, with its<br />

rejection of society and romantic back-to-the-land aspects. Marie<br />

Wurlitzer’s disapproval may account for periods of tension between<br />

my parents that sometimes lasted for days. I never understood the<br />

source of those painful times when my mother and father tried quietly<br />

to ignore each other, but I was well aware of the heavy atmosphere.<br />

They were normally affectionate and happy with each other so it was<br />

10

quite noticeable when something was wrong. I remember the feeling of warmth that radiated to<br />

us children in the back seat when they drove together, talking quietly, my mother’s hand on my<br />

father’s shoulder or sometimes resting on his thigh.<br />

After Pearl Harbor, my father joined the Navy. He had been editing a photography<br />

magazine called Minicam, which was centered on the emerging interest in small, high quality<br />

35mm cameras, like the Leica. Due to his skills as an award-winning photographer he was posted<br />

in Hollywood to direct training films. My mother sadly sold off her herd, many of the prize<br />

animals going to another goat fancier, Paula Sandburg, the wife of Lincoln's biographer, poet<br />

Carl Sandburg. Guessing we might have to stay in California, she sold the farm as well, four<br />

hundred acres of woods and meadows above the Ohio River. We took the Super Chief to Los<br />

Angeles with my mother and a woman from Prague named Leonora Straeka, hired to help out as<br />

cook and nurse maid. A few weeks later when the check from the farm’s buyer bounced, the sale<br />

was cancelled. My parents were happy about this; they had already decided they didn’t want to<br />

stay in the superficial climate of L.A. any longer than necessary, so the farm was rented to the<br />

Brown family. We returned to Ohio at the end of l945 in a dark blue l940 Mercury touring car,<br />

stopping in Santa Fe for midnight mass on Christmas Eve and at the Taos Pueblo the next day,<br />

where I had a snowball fight with a group of Indian boys who were defending their Pueblo from<br />

white invaders.<br />

Mazatlan, July 14<br />

This beach is great. Large bay and ample surf. No Coney Island crowd. Naked boys leaping<br />

like frogs in the froth. From Redlands to Nogales, from Nogales to Hermosillo, from Hermosillo<br />

to Guaymas, we ran the engine slow, to break in the new piston. Rarely faster than sixty, which is<br />

safer anyway with the rough road and all the cows wandering on it.<br />

We stop for food or fuel and a crowd of forty or fifty people gathers within minutes.<br />

Schoolboys are the most intently fascinated with us. They form a silent ring of wondering faces,<br />

jostling each other for the best look. And then the question in shy timorous tones: ‘De donde<br />

vienen ustedes?’ And the first boy to hear passes the amazing answer to the outer edges of the<br />

circle: ‘Estados Unidos!’ If we said ‘Mars’ they would not be more astounded.<br />

At dusk we stop and make friends with campesinos by the roadside. The Latin tradition of<br />

hospitality never fails, and we are invariably invited to eat something, and often to sleep in a bed,<br />

though we usually refuse and spread our sleeping bags on the veranda, or the floor of the parlor.<br />

As an exchange, Naren tells the story of our journey, and the children are invited to sit on the<br />

11

ike and often given a short ride. Slightly detached and formal with adults, Naren has a way of<br />

quickly making friends with children and having them giggling in minutes.<br />

One evening we approach a village in the Sierra Madre with a huge thunderstorm looming.<br />

As the first drops hit we stop at a lantern-lit tienda. The owner leads us behind his store to the<br />

barn and we run the cycle inside. Half the village gathers to watch as we shed our rain-suits and<br />

spread out our sleeping bags on the earthen floor between a mound of shelled corn and a pile of<br />

cobs. The campesinos sit against the wall smoking and talking to Naren as the rain drills down<br />

and a crescendo of church bells rings out, vying with the thunder. Naren answers their questions<br />

about our trip then describes the daunting challenge of the distance that lies ahead. I have begun<br />

to absorb Spanish much as a child learns a mother tongue, simply by being there. It helps to have<br />

studied Latin and French. I’m basking in being as irresponsible as a two year old, one who drives<br />

a motorcycle at 80 miles an hour when the road is clear of wandering cows and slow-moving<br />

oxcarts. I find my position quite enjoyable since it allows me to pursue another role I have not<br />

always been free to enjoy: that of observer, released from all social obligations. I can sit here<br />

and fill pages in this notebook while Naren talks to those around us, and it’s understood that I’m<br />

like a deaf-mute. It’s a new form of being alone, with only slight loneliness. I have no regrets<br />

about taking a leave of absence from Columbia College, a recess that I’m already sure might<br />

never end. And feel lucky that Naren and I liked each other enough to accept the challenge of<br />

making this trip together.<br />

During a break in the storm we go back to the store and our host gives us hot milk with<br />

rice and anise and some tasty round wheat cakes. Then he pours us each a drink of mezcal. With<br />

the storm rumbling in the background, he and Naren talk late into the night about his fear of<br />

atomic war, and he refuses any compensation for feeding or stabling us. I am learning the<br />

phrase ‘Esta en su casa’, which I hear whenever we try to pay for hospitality. ‘This is your<br />

home’. With each passing day it feels more true, a kind of sweet and very real welcome that<br />

implies safety from any storm. It makes me think of how different the people of urban America<br />

are in their sealed off suburbs and reminds me of the people from Appalachia I grew up with.<br />

My mother has help at home from Cora Gullett and Ola Powers, both women originally<br />

from the Blue Ridge, women with psychic stamina who keep their families together as their men<br />

became drunkards, marginalized on the edge of industrial society. Cora showed me where and<br />

when to find wild strawberries, and Ola told me about supernatural powers and how they must<br />

be reckoned with. She also showed me how to make a perfect piecrust. In some ways I feel closer<br />

to these women than I do to my mother. We can joke and hang out and I feel the warmth and<br />

12

tenderness of their affection. They are more relaxed and intimate with me than my beautiful,<br />

high-strung, disapproving and critical mother. They make me feel I can do anything and do it<br />

well. I know my mother loves me in an almost possessive way but I’m pretty sure that I can never<br />

really satisfy her demanding nature.<br />

Mexico City, July 30<br />

In the Sierra Madre of Mexico, it makes no difference that I’m from an exalted world with<br />

an elite pedigree. I’m a deaf-mute people smile knowingly at. It’s time for me to start over, with<br />

no advantages in my favor. Just my memories to support me, and Naren to deal with the world<br />

around us, leaving me free to build a new identity. Or retrace my former one, at least on paper.<br />

We are staying at the Engineers Club in Mexico City, as the guests of one of Naren’s<br />

former classmates. There is a shy girl named Rosa who cooks and serves meals. She has a big<br />

healthy body and a handsome Indian face. She says ‘Buenos dias’ and ‘Buenas tardes’ to<br />

everyone with the same solemn look on her face, and I never hear her say more than that to<br />

anyone, not even to her co-workers in the kitchen. After a few days I gave up on seeing her smile,<br />

so this morning I made a series of looney faces at her and she not only smiled, she broke out<br />

laughing, spilling a bowl of milk and laughing even harder. Now she grins whenever she sees me.<br />

At five in the morning after a mezcal binge with a dozen of these engineering students we<br />

serenade their cook whose name is Lydia, who is fat, forty, who lives in a room on the roof of the<br />

Engineers Club and who after half an hour of full-lunged, three-guitared, whole heart flung song,<br />

comes out in silent, sleepy, abashed gratitude to stand in the light of her room’s door and say<br />

simply, ‘gracias’.<br />

Completing work on the cycle this afternoon. Re-facing the clutch, grinding the valves. I<br />

rode this morning on the unpadded rear fender of an old Triumph 350 twin behind one of our<br />

engineer friends with a cylinder head balanced on my knee, bracing as he wove through the<br />

gnarled Mexico City traffic. Sudden semi-violent contact with a pink Volkswagen. A big and very<br />

irate man examines the crash-bar crease in his pink flank. My friend explains in rapid Spanish<br />

that he is conveying me on important errands because I came from New York and am going to<br />

Buenos Aires and my motor needs repair and therefore a dented bug is of absolutely no<br />

consequence.<br />

‘But my beautiful VW,’ he says with a note of tenderness, ‘it’s smashed.’ Together we find<br />

fifteen pesos and leave the man moaning quietly.<br />

13

Puerto Marques, August 7<br />

We’ve taken a side trip down to Acapulco, and it’s nothing but hotels, gringo-ridden and<br />

unappealing. The son of the Dominican Republic’s dictator Arturo Trujillo is here. He sailed in<br />

on a beautiful four-masted, barque-rigged ship with a clipper hull and is rumored to have flown<br />

Kim Novak down from Hollywood on a chartered DC-6. The gossip on the beach says he will<br />

spend half a million pesos during his stay. A French woman just lost a leg and an arm to an<br />

enterprising shark, and the shark bounty rose to 125 pesos. We’ve retreated from all this and<br />

found a beautiful tourist-free bay a few miles south at Puerto Marques, where we pay two pesos a<br />

night to sleep in hammocks under which the surf runs at high tide. We eat bananas, bread and<br />

fish.<br />

At night the bay is dotted with the lights of fishermen’s dugouts. Bodies gleaming in the<br />

lightning hauling in a net, five on each shoulder-heaved line. If the lead man loses purchase in<br />

the loose sand he moves seaward: an on-going rotation. The net is out about fifty yards from<br />

shore, thirty feet long and ten deep. When they haul it up on shore there are several bushels of<br />

fish to be divided by the fishermen’s wives. Later the men drink beer and play cards. One ageless<br />

man sits at a table, very drunk, watching me with gnome-like, multi-focused eyes. I give him a<br />

cigarette and light it for him. He draws on it and puts it on the table and watches it slowly roll<br />

off. I pick it up and hand it to him and when I look back he is grinning and watching it roll off the<br />

table again.<br />

One of the fishermen is playing a guitar at the table with the drunk; a small crowd gathers<br />

around to listen. The drunk nods and smiles, trying to keep time by drumming on the table.<br />

Music: the dominant sound in my parent’s house is classical music pumped through a hi-fi<br />

system with Voice of the Theater speakers in the living room and smaller ones all over the house<br />

and in the basement workshop and darkroom. My father has a huge collection of 78s. He bought<br />

one of the first players as soon as LP's became available, and the library of discs grew ever<br />

faster. He set up a timer that would turn on the music every morning so we could start the day<br />

with Beethoven, Vivaldi, or Mozart instead of a buzzing alarm clock.<br />

In the milking parlor the radio remains tuned to WCKY, the most powerful voice of<br />

country music in the Midwest; 50,000 watts of Hank Williams, Bill Munroe and the Carter<br />

Family. Country music was part of my working life. It was in the barn that I first heard<br />

"Blueberry Hill" and "Heartbreak Hotel". I knew as soon as I heard Elvis that his kind of<br />

"Hillbilly Music" was not just for me, the goats and the hired men while we were milking or<br />

cleaning up.<br />

14

There was also a herd of sheep for a couple of years, and a few hogs and chickens on the<br />

sidelines. I think now of this period as a<br />

contest between my mother and father to see<br />

which breed of animals would reign supreme<br />

and occupy the growing number of sons my<br />

mother produced, the last of whom, Anthony,<br />

was born when our mother was forty-three.<br />

The goats won out in the end, maybe because<br />

my father was too busy with his career as the<br />

editor of Modern Photography magazine, the successor to Minicam. In l950 my parents decided<br />

to sell off the losing contenders and build a pasteurizing plant. They made a deal to market goat<br />

milk through French-Bauer, the largest dairy company in Southern Ohio. This meant raising<br />

more feed: hay, corn, oats and barley, and that meant more hired men and more tractors and<br />

equipment to work the fields. It was exciting for me. Fieldwork became my passion; glorious<br />

evening and often night-time hours alone at the helm of a Ford-Ferguson plowing, disking,<br />

mowing hay, or cultivating corn. During the spring planting and fall harvest seasons I could get<br />

out of milking because the timing of field work was crucial, and younger brothers could usually<br />

be pressed into service as milkers. Solitude, sunburn and rich aromas. Strong alliances with the<br />

hired men who represented the world of hard work with their no-nonsense, down-to-earth<br />

intelligence, as well as the surreal world of smoking and drinking in bars, and two toned V-8<br />

Ford coupes with richly resonating glass-pack mufflers. We had a natural bond, partly based on<br />

the unspoken fact that they resented my mother being the boss as much as I did. We shared the<br />

feeling that ‘city folks’, (which included my parents), didn’t know what life was about, and that<br />

the work we did was more important than theirs.<br />

Some dogs chase a fat pig down the beach. Squonking, it runs under Naren’s hammock,<br />

knocking him out into the sand. We laugh and buy ourselves beers from the concession stand.<br />

Tomorrow we’ll head back to Mexico City.<br />

Guatemala, August 24<br />

In Mexico City they say the thieves are so clever they would steal the blue from the sky if<br />

the Lord didn’t stop them. So they steal your socks without taking your shoes off. That’s the<br />

warning I heard. Happy to be here and out of the frantic forty-eight. We completed some<br />

additional work on the cycle this afternoon at a great BMW shop run by a dignified sixty year-old<br />

15

German-Mexican named Senor Rowald. On Sunday we’re riding south with him and his group of<br />

avid BMW loyalists on their monthly outing to Puebla. He wears leather pants and his R-60 has<br />

bronze straight pipes that sound great. As good as glass packs on a V-8.<br />

The highway south of Arriaga, in Chiapas, is still being built. All traffic headed for<br />

Guatemala has to be transported to the border town of Tapachula by rail. The freight agent in<br />

Tonala wears a soiled Panama hat and a heavily sweat-stained white shirt with smears of food<br />

and wine from collar to belt. His face is drawn into a bitter cringe and his glass left eye rolls and<br />

dances in its socket behind a milky cloud of mucus. Naren asks him when the next train is leaving<br />

for Tapachula and how much it will cost us to get on it with the cycle. The man says he will put us<br />

on the shipment he’s making up to leave at five that afternoon if we give him twenty dollars.<br />

Naren gives him a quizzical look and asks how the rate is computed. The man looks at us with<br />

seething anger for a couple of minutes in silence. Then he tells us in a voice silky with hate that it<br />

is eight pesos for the first hundred kilos and a peso for each additional kilo. This amounts to<br />

about two U.S. dollars. Naren asks what time we should be there to load and he says 3:00. When<br />

we return at 3:00 the office is locked. After waiting around and then asking some boys if they<br />

know where he is, we find the man at a café on the main square, staring intently at a bottle of<br />

cheap wine. When Naren asks when we are to load he gives us an ugly, triumphant smile and<br />

says the shipment is not leaving that day. I wonder what embittered this man so much. It’s clear<br />

that he tried to cheat us because we are foreigners, but there is more to it than that. He is angry<br />

with everyone and everything.<br />

We ride north to a river we crossed on the way in. There are large smooth boulders with<br />

fast cold water from the purple mountains to the east. Next to the river are cottonwoods and a<br />

knee-high carpet of grass. We take off our clothes and lay in the current. It tugs at our bodies,<br />

brushing fine grains of sand lightly against our skin. We sleep there and next morning we hoist<br />

the cycle into a baggage car after paying thirteen pesos, allowing us to take the train ride over<br />

the border to Tapachula where the road begins again.<br />

El Cerrito<br />

I can see that transcribing all these journal entries is going to be a major effort. But<br />

I’m happy with the main entries and surprised by how much is worth keeping. Maybe it’s<br />

a chance to go deeper and produce something more revealing than any of my films or the<br />

things I’ve written. I’m glad I finally broke down and bought a 23 inch cinema display<br />

16

screen for the computer, so I can work here with less electronic buzz. It’s better for editing<br />

film too.<br />

Sitting here looking out at the San Francisco Bay I know there were mistakes more<br />

serious than dropping out of Columbia. A pattern of doing what my friend Kay describes<br />

as yielding to my lazy side. What she means is a tendency to not push deeper in my work<br />

and fail to achieve what she believes I’m capable of, which allows me to say at some<br />

point, “Far enough. Time to move on.” She’s right of course, but I think it would be more<br />

accurate to call it impatience. Maybe that essential American habit of always being ready<br />

to hit the road if things are hard or seem dull. It’s true that I was seduced early and forever<br />

by the allure of the road. The legacy of the frontier: there’s always another, brighter<br />

chance on the horizon. Or maybe I’m just hiding from my laziness behind an existential<br />

state of mind about how the world works? I decided early on chasing success would be a<br />

sucker’s game that would keep me from living in the moment, and that we’re all denying<br />

our mortality; taking ourselves too seriously.<br />

At nineteen I was definitely enmeshed in my romantic fantasies. I didn’t guess<br />

what was in store for me or what a poor husband my quest for adventure would make me.<br />

My idealistic dreams about love were based far more on reading than experience. As a<br />

farm boy I was familiar with the lust of the goat, but my agnostic side kept me from<br />

punishing myself about the equivalent in myself: no burden of guilt about sin. But I didn’t<br />

guess how much more powerful biology and hormones are than dreams of a loving<br />

partnership. Having escaped my domineering mother I didn’t want to see how vulnerable I<br />

still was to the sexuality of powerful women. I thought I knew who I was, but awareness<br />

of my failures made me avoid looking too close.<br />

I hated the rules that all seemed to support a phony culture, so I figured it was best<br />

not to join the team and just invent my own game. Dropping out was a good start. I<br />

hadn’t made many friends, or connected with Columbia, so it was no more a lonely road<br />

than I was already on, but much more appealing. Today I don’t feel any regret about<br />

those impetuous youthful decisions; in fact, I’m glad I made them since they launched me<br />

on a more interesting life than I might have had otherwise. It’s clear to me now that they<br />

were a series of detours from the task of looking deeply at myself. That my whole life has<br />

17

een like a road movie. Now I get to step away from behind my camera and my<br />

adventures and figure out what my life is about. And what it was about.<br />

On my way to the bank this morning I saw several people rush to the aid of a<br />

well-dressed, elderly gentleman who had tripped in the crosswalk and smashed his face<br />

which was bleeding profusely. I decide there's nothing I can do and continue hobbling to<br />

the bank, leaning on my cane. It's gratifying to notice how many people were concerned.<br />

I can't help wondering if there would have been any help for a shabbily dressed man. Or<br />

a healthy looking greybeard like me. Probably less. On my way back I see the wounded<br />

man surrounded by people and propped up on the sidewalk as an ambulance pulls up.<br />

There are large splotches of blood on the sidewalk and a woman is holding a white<br />

handkerchief over the man's nose.<br />

I come home and over a tamale for lunch I read a piece about Joe Mitchell in the<br />

New Yorker. For years he wrote ‘Talk of the Town’ entries. Would he have joined the<br />

crowd and tried to talk to the wounded man? I realize it's not my nature to do that. If it<br />

had been a fight or dispute I might have lingered to watch. If I could have helped—and I<br />

would have tried if it had happened close to me—that would have given me a way to<br />

connect. What seems to fascinate everyone most about Mitchell, once they finish<br />

praising his work, is that he wrote nothing for the last 30 years of his life, though he sat<br />

at his New Yorker desk nearly every day during all those years. And none of the editors<br />

put any pressure on him to produce. Apparently he was at peace with it.<br />

I can easily identify with his silence those last years as I learn how to accept and<br />

live with my disability. There are days now when it all seems such a charade that there's<br />

really not much worth saying. Or doing. It's a peaceful kind of nihilism. Far more<br />

bearable than earlier and more depressed versions. More like an extreme sort of<br />

detachment--an almost historical perspective about how brief and meaningless our lives<br />

are, re-enforcing my commitment to recognize every significant moment and relish the<br />

most fleeting images of love. There's sadness in it but it's more like resignation than<br />

sorrow. I’ll need to flip that mood into productive introspection and say some<br />

uncomfortable things about myself and my family if I really want to write this book.<br />

18

Neither of my parents grew up on farms. My father was the son of a civil engineer<br />

and lived through high school in Troy, Ohio. His great-great grandfather Jacob was one<br />

of the first white settlers in Miami County, having been given a land grant by the<br />

Continental Congress for fighting the British during the revolutionary war.<br />

My mother was raised in the magical kingdom her father Rudolph Wurlitzer<br />

created in a lush suburb of Cincinnati. The house was a multilayered turn-of-the century<br />

castle with an indoor, heated swimming pool on the lowest level, squash courts above<br />

that and a teak-floored music room on the next level. There was a Wurlitzer theater organ<br />

19<br />

at one end and a small room for a<br />

collection of Stradivarius and<br />

Guerneri violins and violas in glass<br />

cases on one side. In another alcove<br />

was a player-piano, but there were no<br />

jukeboxes in sight. They weren’t<br />

proud of the product that saved the<br />

company after the depression. I think<br />

they were too snooty. A few steps<br />

above the music room was the dining room with a massive circular mahogany dining<br />

table centered in a half moon of French doors with a view of the gardens. The table was<br />

mounted on a motorized platform concealed by a rug. My grandfather loved to entertain,<br />

and there was a steady stream of noteworthy guests from the world of music, theater and<br />

the arts at his table. At the beginning of a meal my grandfather simply threw a switch and<br />

the table would turn noiselessly and imperceptibly while the wine and food was served. It<br />

made a complete revolution every hour and a half. At the end of several courses,<br />

heightened by excellent wine and animated conversation, many an astonished guest<br />

would find himself looking into the depths of the music room after having begun the<br />

meal looking out into the gardens. I grew up hearing my mother and her sisters chuckle<br />

about this prank and also how I made pianist Arthur Rubinstein laugh by jumping on his<br />

lap when I was two.

The gardens were on several levels, with a lake at the bottom of a forested ravine.<br />

On the far side of the lake was a two-story log cabin with bunk beds on the second floor<br />

and a rustic kitchen below; a life-sized dollhouse for my mother<br />

and her sisters to play in. Further along the lake was a cave<br />

carefully contoured with jagged cement stalactites. In the depths<br />

of the cave a steel pipe was hidden in the ceiling and covered<br />

with a stone in the grass above. The pipe could be blown into like<br />

an instrument to produce bear sounds that terrified and delighted<br />

children in the cave. Beyond the cave was a tree house in a<br />

massive oak. My grandfather had created this fairyland to entertain his children, and it<br />

clearly reflected his playfulness and good taste. Since he died when I was nine, I never<br />

got to know him. I only found out last year that he was a member of the Unitarian<br />

Universalist Church and that his Catholic wife, Marie, was ex-communicated for<br />

marrying him. My strongest memory is his happy grin as he passed out handfuls of dollar<br />

bills to the throng of prancing grandchildren surrounding him at family parties when he<br />

called out, “Who needs a dollar?”<br />

Subsequent years produced more painful memories about the Wurlitzer legacy as I<br />

grew to disdain it and feel uneasy around most of my aunts and uncles, who seemed like<br />

upper crust bigots and anti-Semitics. They were far more sophisticated than Archie<br />

Bunker but equally mean-spirited.<br />

I couldn’t ignore the irony that I was dating a Jewish beauty whose family were<br />

anti-goy and never would accept mine or me.<br />

Guatemala, August 25th<br />

On the main street of a town in Guatemala this morning we sat on the cycle watching a<br />

funeral procession circle the plaza. A wizened crone stands in the crowd of sloe-eyed, solemn<br />

people who hang about looking at us in a dumb lethargy of disbelief while waiting for the<br />

procession to move on. The old woman leans on a cane pole. Her body is wound in unwashed<br />

rags held together by bits of string and wire. She holds out a wrinkled hand to us and, receiving<br />

nothing, shakes her pole at us vindictively. Then she stands watching, her eyes darting about like<br />

threatened goldfish. Whenever a child wanders too close she reaches out with her pole and pokes<br />

it viciously.<br />

20

A boy of about six wanders up and, intent on watching us, he does not see her behind him.<br />

She reaches out and gives him a poke in the back, and he stumbles forward and turns to her with<br />

angry tears in his eyes. She takes a step forward and jabs him in the stomach, and he runs down<br />

the street howling. She looks about proudly, a faint smile of gloating satisfaction playing about<br />

her mouth. A boy of about ten sees the other boy running away, sees her, and comes up to the<br />

edge of the crowd, where he stands for a minute looking us over with an alert intelligence none<br />

of the other faces, except the old woman’s, show. Then he moves quietly up behind her, grabs<br />

her pole, wrenches it away from her and flings it into the street. She curses him and orders him<br />

to return it, kicking at him as he dances just out of her range. He laughs at her, the crowd echoes<br />

him hollowly and she begins to cry.<br />

A three-minute medieval passion play, with cruelty, violence and justice.<br />

San Jose, Costa Rica, September 5<br />

We’ve been making some serious miles and now we need to get more work done on the<br />

bike. We present ourselves to the VW/BMW agency here and explain our limited finances. Phone<br />

calls are made and lackeys dispatched to have welding done, procure a new rear tire, new roller<br />

bearings for the rear wheel, a new tail-light. All the work and parts are supplied to us gratis and<br />

free for nothing. We stay with our new friend, the star salesman of the agency, a Colombian and<br />

a generous sort, who’s treating us like lost brothers. There are enough nationalities working at<br />

the agency to help us get visas for the rest of the trip. Visas have been a pain in the ass and an<br />

expense. Panama wants to see tickets in and out of herself plus five bucks a head for a 72 hour<br />

visa. That could be impossible for us, but its been taken care of now.<br />

On these last legs through Central America we continue to improvise our shelter. I’m<br />

grateful for Naren’s quick wit and skill at pulling this off, especially in the cities. It’s much more<br />

interesting and far cheaper than staying in hotels and it’s a way of connecting with real people<br />

in each new place. In San Salvador we slept in the park at the center of town after making<br />

friends with a gardener who let us put the bike in a tool shed. In Managua we struck up a<br />

conversation with a teenager who invited us to his home where we slept on cots in the parlor.<br />

His mother's kitchen had a spring-fed well one hundred and forty feet deep. She cooked us a<br />

splendid simple meal and smiled quietly to acknowledge our thanks. The warmth and purity of<br />

these chance encounters are one of the great rewards of the journey.<br />

In Honduras we spend a night in an army barrack, and in northern Costa Rica with the<br />

Feluco Construction Company, who are building the Pan American Highway. We reach their<br />

camp just at dusk and a foreman invites us to spend the night. Dump trucks, D-8’s, earthmovers<br />

21

and graders all drawn up in orderly array. Rows of barracks, workshops and a huge cook shack.<br />

A long dining hall which feeds 125 men three times a day in lumberjack quantities. The men get<br />

50 cents an hour, room and board; they work six days a week and are transported to their homes<br />

for a three-day break every second week. They are a happy bunch.<br />

At a gas stop in Honduras we have a brief encounter with a pimple-faced teenager from<br />

New Orleans who reminds me of an America I don’t miss. This kid is traveling with his father in<br />

a new Cadillac, moving to Tegucigalpa to join an uncle in the lumber business. The sad part, he<br />

told me, was leaving behind his ’57 Chevy with a Corvette engine. But the consulate in New<br />

Orleans told him there wasn’t a drag strip in all of Honduras. “Jesus man,” he says. “I don’t<br />

know what I’m going to do down here. I don’t know about where you come from, but in<br />

N’Orleans the cats are purely car crazy. That’s all they think about. I mean not even girls. A girl<br />

is just another accessory you put in your car, like a four-barrel carb.” I don’t bother to tell him<br />

that I’ve been more plane crazy than car crazy.<br />

In the early 50's my father graded an l800 foot landing strip into one of the ridge-top<br />

fields and put up a windsock. It was a moment he was proud of and one I had dreamed of. Before<br />

long there was a four-place Cessna l70 tied down by the side of the strip. I learned to fly in that<br />

plane and soloed on my sixteenth birthday after one hour of flight time with a licensed instructor<br />

in an Aeronca Champ. First time I ever flew one of those, but no problem. The instructor laughed<br />

and said he was turning me loose to solo after taking a little ride with me. In the afternoon I took<br />

my driving test, a formality that seemed ludicrous, since I had been driving on and near the farm<br />

for years.<br />

A week later I found a Piper Vagabond in Trade-a-Plane at the nearby Blue Ash Airport.<br />

It cost me 800 dollars, money I had made working on the<br />

farm over the years. My father dropped me at Blue Ash<br />

and I flew out to circle the farmstead, calling down to my<br />

waving brothers, “come out and see it”, then I did a long<br />

swoop over the river, ending in a chandelle, after which I<br />

landed and parked next to the windsock. They came out on<br />

their bikes, Kit in the lead, then Rick and Roddy. My<br />

mother drove out with two year old Tony. I could see pride<br />

and a little awe in their faces. They crowded around the plane and I put Roddy and Tony in the<br />

cockpit and showed them how to move the joystick and watch the ailerons go up and down. I was<br />

glad I hadn’t bought a car, which some of my classmates were doing as they turned sixteen,<br />

22

primarily so they’d have more freedom to pick up girls. I was proud and more than a little<br />

arrogant about being the only junior at Walnut Hills High School with his own airplane and a<br />

license to escape the mundane world of my peers any time I wanted; elated that I was strong<br />

enough to chart my own course.<br />

Puntarenas, September 9<br />

Forty miles south of San Jose, Costa Rica, the highway turns into a trail we’re told is<br />

virtually impassable, even on foot and using a sharp machete. It might take weeks to hack our<br />

way through, so we choose to do a portage down to the Canal Zone from the Pacific port of<br />

Puntarenas. In the end, this may also take several weeks, since we are repeatedly refused free or<br />

'workaway' passage by each of the freighters that’s docked here on its way south.<br />

Puntarenas is a few blocks of sandy streets with a couple of restaurants and several bars<br />

on an isthmus shaped like a half pear. It smells of oranges, fish, stale urine, diesel, creosote and<br />

old wood rotting in the tropical air. We’re sleeping in a house under construction, having made<br />

friends with the head carpenter, and we hang out each day under the palms on the port side<br />

esplanade, waiting for the next freighter, sitting at one of the three cafes, the ‘Blanco y Negro’,<br />

the ‘Rancho Grande’, or the ‘Rio de Janeiro’. There are prostitutes working the sailors at the<br />

cantinas and bars but Naren and I have neither the interest or money for them. I have plenty of<br />

time to dream about Judy and write entries in my journal. Yesterday I imagined myself back at<br />

home on a lazy Sunday afternoon, and I sketched a satirical four-page play poking fun at my<br />

mother’s campaign to worm all the goats, interwoven with my father’s search for a missing blue-<br />

handled trowel.<br />

As the dairy herd grew to nearly 400 goats there was a scourge of incurable viruses and<br />

inexplicable tumors. This lasted more than a year. My mother was increasingly frantic and<br />

frustrated when the veterinarian she trusted had no solution. There was talk about the trials of<br />

Job and the merciless injustice of the natural world. She created isolation pens and treated the<br />

sick animals with endless injections of antibiotics and serums but her fear about the sick ones<br />

contaminating the others led to days when it was my turn to load a dozen or more goats in a<br />

trailer and drive out to a gulley at the end of the landing strip with a 22 caliber pistol in my belt. I<br />

would shoot each one in the back of the head as the others watched with what I’m sure was stark<br />

terror. Then I had to drag them all to the bottom of the gulley and shovel enough earth over them<br />

to keep any marauding dogs off. It was a desolate ritual that haunts me still. These were often<br />

animals I had milked twice a day for years. Animals whose kids I had helped deliver. Animals<br />

who each had a name and a history with us humans. I looked at that pistol with revulsion. The<br />

23

size of our herd had thrown everything out of balance. I wondered if my parents knew the<br />

meaning of what they were doing and if running the biggest goat dairy in the Midwest made any<br />

sense. Especially if it required killing my Nubian and Alpine friends. Eventually the pathogens<br />

moved on and this reign of terror was over, but the questions remained about the forces of nature<br />

and how I should relate to my parents’ effort to succeed in the world of commerce.<br />

I wonder how strong a psychic hit all this has been for me. It launched me firmly on the<br />

road to pacifism and was confirmation of my thoughts about the dark side of life. I expect the<br />

worst and sometimes doubt my right to anything better. I don’t trust fate to be benevolent nor<br />

human nature, including my own, to be beyond suspicion.<br />

This morning I watched as a boy punting a ball down the paseo kicked his shoe off and up<br />

into a plane tree. Then he threw the ball at the shoe, and it hung like a ripe grape where the shoe<br />

had been. He threw the shoe, and it joined the ball in the tree. He threw his remaining shoe and<br />

everything came back down. He gave a joyful chortle and went on down the esplanade. This<br />

panoply of life and the freedom to sit and watch it is the education I am looking for. We’ve come<br />

9000 miles over these past two months and spent 400 dollars, most of it on the bike. Two hotel<br />

nights so far. Between us we have a bit more than 100 dollars left. Things are cheap down here<br />

and we’re very frugal, but maybe we’ll need an infusion. Gasoline is rarely more than ten or<br />

twelve cents a gallon. The comida corriente at the Hotel Pacifico is 22 cents or 2 colons with<br />

salad and a glass of milk. It’s costing a dollar apiece a day for us to live here. We’d rather not<br />

live here any longer. The captain of an American tanker, the ‘Gulfabo’ said he would take us to<br />

Panama, then changed his mind and wished us luck.<br />

Gunter, the German second mate on the ‘Magdeburg’ had five ships torpedoed and<br />

bombed out from under him in the Mediterranean. In 1943, disabled, his freighter put into<br />

neutral Barcelona. An hour later a British destroyer was docked next to them in such a way that<br />

their flags crossed. Gunter and a shipmate went ashore and took the last table in a crowded<br />

restaurant. A few minutes later two British officers came in and were seated at the same table, the<br />

only one left with vacant seats. Shock and horror on both sides. They ignored each other but by<br />

the end of the meal were drinking together and after several bottles of wine were wondering why<br />

they should fight each other.<br />

Every week or so I buy an envelope and go to the post office to mail the journal back to<br />

Judy. She is my Penelope; making her my muse keeps me from missing her too painfully. I’m<br />

asking her to write me care of Thomas Cook & Sons in Quito, Ecuador, the first place I can be<br />

24

pretty sure that there will be a Cook’s office. Just trying to stay in touch has become rather<br />

surreal.<br />

A pair of American missionaries come by and ask if they can join me here at my table in<br />

front of the Blanco y Negro. I say sure and go on writing as they order a pipa. “You’ve got to try<br />

it, Herb. It’s coconut milk.” The older one is stocky, sport shirted, balding, soft-spoken and has a<br />

delicately done tattoo of Our Savior on his left ear lobe. Really. The younger is a gangling six-<br />

footer wearing an ivy-league shirt, whose most distinguishing feature is his blatantly protuberant<br />

upper front teeth.<br />

I offer a Tico cigarette and the elder one says primly, “Thanks, but I can’t smoke because<br />

I don’t have a chimney.” I light up anyway, without a chimney. A single pipa arrives and they<br />

bend over it like a teenage couple at the corner drug.<br />

“Well, how do you like it, Herb?” Coy giggles from Herb, who admits he doesn’t like it<br />

much. “Come on, Herb. Drink up, fellow. Good for you.” Herb fiddles unhappily with his straws.<br />

“Herb, shame on you. The level hasn’t gone down at all.” Elder bends over and finishes it. I’m<br />

not sorry to see them go and I get back to my journal entries about growing up on the farm,<br />

which is probably four thousand miles due north of where I’m sitting.<br />

My Piper was a two seat, 65 hp, fabric-covered yellow beauty that suited me, though it<br />

didn't entirely fulfill my fantasies of historic fighters like Spads and P-5l’s and Spitfires. But it sat<br />

there waiting for me, ready to fly up the river at water level, under an isolated bridge once, and<br />

under power lines more than once. I soon thought of its wings as an extension of my arms and<br />

made it a point of honor to clip a sprig of maple leaves with my tail wheel from the tree at the<br />

south end of the field every time I landed to the north. I loved the tangy perfume of high-octane<br />

aviation gas filling the air when I opened the petcock below each fuel tank to drain any water that<br />

might have gathered from condensation. I relished the ritual of turning the engine over with the<br />

wooden propeller a couple of times to prime it before switching on the ignition and giving the<br />

prop a hefty pull to fire the Lycoming. I could then kick the wooden chocks out from in front of<br />

the wheels, jump in the cockpit, and taxi to the end of the runway.<br />

I easily flew the required hours of cross-country, passed the various written exams and<br />

was ready for the private pilot's test as soon as I was eligible, on my seventeenth birthday. I<br />

passed it that afternoon and flew home to take my brother Kit for a ride. We flew north to visit<br />

Lindy Grey, the former hired man who was now working on a farm about sixty miles from ours. I<br />

25

circled the hayfield next to the farmstead and landed up-hill, up-wind through some freshly<br />

windrowed hay.<br />

We walked to the house and found no one home. It was a hot, humid evening at the end of<br />

May. The air was still and the light beginning to fade when I decided to take off. I had a choice:<br />

up hill with only a light, occasional puff of breeze, or down hill, taking a chance on no breeze. I<br />

bet on the latter, and poised at the top of the field watching the grass along the fencerow until<br />

there was no movement, then I gunned it. At the bottom of the field I didn't have enough lift to<br />

clear the double fencerow. As we plowed through the wire I switched off the engine to diminish<br />

the chance of fire, then climbed out and picked up a chunk of the splintered wooden propeller and<br />

smashed it over the engine cowl in disgust. Then I turned to Kit and gave him a fierce shake,<br />

saying, “It’s all your fault; without your extra pounds I would have made it.” Then I laughed and<br />

hugged him. He grinned and laughed his wry laugh and said, “ I’m sorry. Real sorry we didn’t<br />

make it over the fence. How are we going to get home?”<br />

The right wing hung limply, disengaged from the fuselage by a blow from a fencepost.<br />

When Lindy arrived a few minutes later, he drove us home. No one said much. I developed some<br />

fancy theories about convection currents and inversion layers caused by the hot weather and<br />

topography of the hayfield and about the new prop Moose had sold me to increase my cruising<br />

speed. Really, I knew I’d made a poor decision: the field was too short for a windless take-off and<br />

my luck had simply run out just before I reached the fence. It would have been much worse if<br />

either of us had been injured.<br />

A few days later Moose arranged the sale of the Piper Vagabond for two hundred dollars<br />

to an A&E mechanic who had it flying three weeks later. He hauled it out of the hayfield and I<br />

reimbursed Lindy’s boss for the fence repair. I joined a flying club, which gave me access to<br />

three Cessnas at low hourly rates. I flew a 170 to pick up my sister Janet and her friend Seaweed<br />

at Carlton College in Minnesota. Over the next year I racked up nearly two hundred hours of<br />

flying time before leaving the farm for New York City. I was a lucky farm boy living my dreams of<br />

being a pilot, but ready to trade them for the Big Apple.<br />

I had a pretty good year at Columbia after dropping all the required courses at the<br />

beginning of the first semester. I was able to join a lecture course taught by critic Lionel Trilling<br />

and a junior class seminar on American literature with Quentin Anderson, the son of playwright<br />

Sherwood Anderson. These classes dealt with the territory that interested me. I had already<br />

disqualified myself from graduating when I dropped out of the required weekly lecture on the<br />

history of the University, failed to sign up for physical education and repeatedly absented myself<br />

26

from "Sexual Education". That requirement made me feel I was back in high school. I didn’t<br />

want to study medicine or law or become a teacher, so what did I need a degree for? I was ready<br />

to do anything to avoid getting stuck in the conformist bourgeois traps America had set for me<br />

and my peers to keep us in line during the frenzy of 50’s prosperity. I wanted adventure.<br />

All winter I was a glutton for the cultural benefits I came to New York City to feed on.<br />

The main reason I chose Columbia. It was all a short subway ride away. The village. Jazz clubs.<br />

The ‘Five Spot’ to hear Charlie Mingus. Cecil Taylor playing at a café on Bleecker Street.<br />

Theater on and off Broadway. Richard Burton in “Look Back in Anger”. Jason Robards and<br />

Lauren Bacall in “The Iceman Cometh” with my high school friend Judy Denman. After the<br />

play, by pure chance, we ended up sitting next to Robards and Bacall at a bar across the square<br />

from the theater. We drank and talked with them until closing time and then at their apartment<br />

until four that morning. They seemed to understand my decision to drop out of Columbia and<br />

head for South America, and asked me what I wanted to write and who my writing influences<br />

were. Not a word of patronizing or paternal advice. They wished me success on my journey, and<br />

Judy on her studies at Radcliff. They might easily have ignored us in the first place. They must<br />

have thought we were interesting so they adopted us for a few hours. It made me feel lucky and a<br />

bit special.<br />

Shortly after that I went to see my cousin Sally at her tenth floor apartment down in the<br />

fifties on the east side. She had been in France for several months and told me she was sad about<br />

the end of an affair in Paris. Then she surprised me by unbuttoning her blouse and showing me a<br />

couple of hairs growing next to her left nipple. Did I think that could be why the affair had gone<br />

wrong? No, I said, that couldn’t possibly be why. I said it was a beautiful breast and assured her<br />

she was a lovely woman and said maybe he was just a prissy fool. Sally and I had always been<br />

close and loved talking to each other about books and life and loves, and our strange family. We<br />

once spent a whole afternoon talking, facing each other on a leather couch in my parent’s living<br />

room. Then we drove to Yellow Springs to see a performance of King Lear at the Oberlin<br />

College annual summer Shakespeare festival. Two years later in her apartment, I tried to<br />

comfort her, but not effectively enough to keep her from throwing herself from the fifth-floor<br />

window a month later. I wished I had seen the need to do more, and maybe kissed the nipple<br />

instead of just kissing her cheek like a proper cousin.<br />

I suffered a severe slump in my spirits. I felt sad and confused. I wondered what I was<br />

doing there, trying to read 2000 pages a week. I had never had any therapy but had read some of<br />

Freud’s Basic Writing and was curious about it all, so I took advantage of a student privilege and<br />

27

went to a staff Adlerian psychiatrist at Columbia. Cold, with a pinched demeanor, his first<br />

question, without any preamble, was, “Why do you hate your mother?” I answered that I didn’t<br />

hate her any longer and that my depression was not about her, but about death and winter in New<br />

York and the meaningless work I was doing at Columbia College, not to mention my frequent<br />

desire to say the unsayable. He was a sour, pug-faced man in his thirties and didn’t pick up on<br />

my attempted joke about Wittgenstein. He scowled at me intently and reiterated that the first thing<br />

he needed to know was why I hated my mother. I had actually finished years of battling my<br />

mother and come to understand her and love her but he was the last person I wanted to tell about<br />

that. I decided there was no chance he was going to provide the help I wanted. I said I could<br />

easily explain, without any formulaic questions, why I might grow to hate him, if he was<br />

interested. He was stuttering with surprise and indignation as I stood up to leave. It was soon<br />

after this that I dropped the Contemporary Civilizations course with its excess of reading and<br />

started talking seriously to Naren about going to South America, which I hoped was all the<br />

therapy I needed. Unless I suddenly found myself hating my mother. Or anyone else.<br />

In the ‘Café Botecito’ yesterday I met two Iowa dairy farmers. They are Quakers, part of a<br />

growing colony at Monte Verde, with three thousand acres at five thousand feet, adjacent to a<br />

rain forest. They moved down here and bought land several years ago to escape the militarism of<br />

the United States. Both have done prison time for refusing to serve in the U.S. army. They have a<br />

herd of Guernsey cattle and are the sole cheese producers in Costa Rica. They invite Naren and<br />

me to visit, but we decline, since we are afraid we’ll miss a boat. I am fascinated by their<br />

commitment to pacifism and the description of what they’ve been through, leading to the decision<br />

that they must leave the United States.<br />

El Cerrito<br />

Thirty years later I did get to Monte Verde. I went there with Julia Whitty to<br />

document the rain forest, which these same Quakers had helped turn into a national park.<br />

Julia and I were there to work on a film she was making with Hardy Jones. We stayed at<br />

the bed and breakfast on the Quaker dairy farm, and I felt the hand of time brushing me<br />

as I searched for the faces of the two farmers I had met as a vagabond of nineteen.<br />

Last night I dreamt I was in Mexico in a beautiful colonial town like Veracruz.<br />

Lots of great old American cars in perfect shape. A Studebaker backed up in front of me<br />

on a tree-lined street to find a parking place. There was a guy with me carrying a piece<br />

of meat wrapped in wax paper. It was a perfectly split half of a lamb. At some point it<br />

28

ecame cooked and he laid it on its wrapping in the street and we sat on the curb<br />

watching the old cars go by. Finally I reached out and took a chunk of the meat to<br />

sample. Then to my surprise the guy squirted lighter fluid on a portion of meat and lit it,<br />

explaining that he liked his meat warm. I joined him in tasting the warm meat after the<br />

fluid burned off.<br />

I am amazed, as always, by the power of the dream world. I wonder if this one<br />

was triggered by reading the journals and remembering the excitement of those days on<br />

the road. I feel totally incapable of analyzing my dreams. I consider them by far the best<br />

films I make and since they are so much better, quicker and easier to create I’m just<br />

sorry the audience is so limited.<br />

Today, in El Cerrito, on the 40 th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s<br />

assassination, I watch four eloquent black Americans talk about King’s legacy on the<br />

NewsHour, and I wonder if there’s a way I might be more involved in confronting the<br />

American dilemma than I am writing this book. Back when I was an active filmmaker<br />

and cameraman it was a life of engagement on many different levels. Being part of an<br />

attempt to report the truth was always a satisfying challenge, especially working with<br />

Elizabeth Farnsworth for the NewsHour, since they had an ethical voice and a large,<br />

intelligent audience. Making longer documentaries about guerrilla wars in Salvador,<br />

Nicaragua and Eritrea had elements of connection too: a feeling of kinship with the<br />

underdogs fighting for survival.<br />