The green colonial heritage: Woody plants in parks of Bandung ...

The green colonial heritage: Woody plants in parks of Bandung ...

The green colonial heritage: Woody plants in parks of Bandung ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 106 (2012) 12– 22<br />

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect<br />

Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g<br />

j ourna l ho me pag e: www.elsevier.com/locate/landurbplan<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>green</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> <strong>heritage</strong>: <strong>Woody</strong> <strong>plants</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>parks</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>, Indonesia<br />

Sascha Abendroth a,b,∗ , Ingo Kowarik b , Norbert Müller a , Moritz von der Lippe b<br />

a University <strong>of</strong> Applied Sciences Erfurt, Department Landscape Management & Restoration Ecology and Head Office URBIO, Leipziger Straße 77, D-99085 Erfurt, Germany<br />

b Technische Universität Berl<strong>in</strong>, Department <strong>of</strong> Ecology, Rothenburgstraße 12, D-12165 Berl<strong>in</strong>, Germany<br />

a r t i c l e i n f o<br />

Article history:<br />

Available onl<strong>in</strong>e 9 January 2012<br />

Keywords:<br />

Exotic species<br />

Horticulture<br />

Ornamentals<br />

Plant design<br />

Java<br />

1. Introduction<br />

a b s t r a c t<br />

European design styles strongly <strong>in</strong>fluenced the development <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>parks</strong> <strong>in</strong> many tropical cities (Faggi & Ignatieva, 2009; Lawrence,<br />

1993; Santos dos, Rocha, & Bergallo, 2010). Early Europeans sought<br />

a controlled landscape to create nostalgic memories <strong>of</strong> the home<br />

and resist disorderly jungle (Warren, 1991). One characteristic <strong>of</strong><br />

European gardens is the use <strong>of</strong> non-native species, which can prevail<br />

over the planted species assemblages (Säumel, Kowarik, &<br />

Butenschön, 2010). <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>terregional species pool could<br />

homogenize the species composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>green</strong> spaces <strong>in</strong> cases <strong>in</strong><br />

which widespread non-native species (<strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> native species)<br />

are abundantly planted. Furthermore, the use <strong>of</strong> exotic species is<br />

l<strong>in</strong>ked with the risk <strong>of</strong> biological <strong>in</strong>vasions. Horticulture is a major<br />

pathway <strong>of</strong> plant <strong>in</strong>vasions, and plantations <strong>of</strong>ten function as the<br />

foci <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>vasions (Dehnen-Schmutz & Touza, 2008; Kowarik, 2005;<br />

Mack, 2000).<br />

∗ Correspond<strong>in</strong>g author. Present address: Weitl<strong>in</strong>gstraße 103, D-10317 Berl<strong>in</strong>,<br />

Germany. Tel.: +49 30 48814016.<br />

E-mail addresses: abendroth.sascha@gmx.de (S. Abendroth),<br />

kowarik@tu-berl<strong>in</strong>.de (I. Kowarik), n.mueller@fh-erfurt.de (N. Müller),<br />

moritz.vdlippe@tu-berl<strong>in</strong>.de (M. von der Lippe).<br />

0169-2046/$ – see front matter ©<br />

2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.<br />

doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.12.006<br />

Colonial garden architecture with associated use <strong>of</strong> non-native plant species <strong>in</strong>fluences the identity <strong>of</strong><br />

many tropical cities. In Indonesia, <strong>colonial</strong> planners argued for plant<strong>in</strong>g both native and non-native<br />

species. It rema<strong>in</strong>s unclear how far this suggestion was implemented <strong>in</strong> urban <strong>parks</strong> and if species proposed<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> period still occur <strong>in</strong> the <strong>parks</strong> or got replaced by common non-native species, which<br />

are prevail<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> other tropical cities. We first analyzed recommendations on the plant use <strong>in</strong> conceptual<br />

publications on the design <strong>of</strong> <strong>green</strong> structures <strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>. We then <strong>in</strong>vestigated species<br />

pools <strong>of</strong> planted woody species <strong>in</strong> differently aged <strong>parks</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong> to test the hypothesis that remnants<br />

<strong>of</strong> historically recommended species are still present <strong>in</strong> the <strong>colonial</strong> <strong>parks</strong>. We anticipate that native<br />

species still exist <strong>in</strong> older <strong>parks</strong> while more recent <strong>parks</strong> show an <strong>in</strong>creased percentage <strong>of</strong> non-native<br />

species that do not belong to the historical assemblages <strong>of</strong> woody species. <strong>The</strong> results show that species<br />

recommended <strong>in</strong> historical concepts occur more <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>in</strong> such <strong>parks</strong> created <strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> times, than <strong>in</strong><br />

younger <strong>parks</strong>. Contrast<strong>in</strong>g to other <strong>colonial</strong> cities, historical plant<strong>in</strong>g concepts for <strong>Bandung</strong> equally recommended<br />

native and non-native trees and a considerable number <strong>of</strong> species from local Javanese flora<br />

were proposed for city <strong>green</strong><strong>in</strong>g. However, <strong>in</strong> the recent species assemblages, non-native species clearly<br />

prevail (65%). It is thus challeng<strong>in</strong>g for the future development <strong>of</strong> the <strong>parks</strong> to raise awareness <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>green</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> <strong>heritage</strong> and to strengthen the use <strong>of</strong> native species.<br />

© 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.<br />

Colonial garden architecture and plant use can alter the local<br />

identities <strong>of</strong> cities <strong>in</strong> different ways. Design elements that comb<strong>in</strong>e<br />

landscape features with scattered trees, vistas, water bodies,<br />

flowerbeds, and flow<strong>in</strong>g lawns mostly reflect the <strong>in</strong>fluences <strong>of</strong> the<br />

English landscape garden (Ignatieva & Stewart, 2009). Characteristics<br />

<strong>of</strong> tropical gardens, especially <strong>in</strong> royal palaces, are <strong>plants</strong><br />

with high symbolic mean<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>plants</strong> with medic<strong>in</strong>al and foodstock<br />

uses. <strong>The</strong>se features reveal old Asian philosophies <strong>in</strong> which<br />

even royal landscapes appear both practical and aesthetic (Warren,<br />

1991).<br />

A loss <strong>of</strong> local identity is <strong>in</strong>duced when traditional garden elements<br />

<strong>in</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g cities are transformed or replaced by western<br />

garden culture. Yet, with<strong>in</strong> newly founded <strong>colonial</strong> towns, <strong>green</strong><br />

elements and architecture from <strong>colonial</strong> times belong to the specific<br />

urban history and consequently contribute to the identity <strong>of</strong> these<br />

towns (Cobban, 1992; Wiltcher & Affandy, 1993). Analogous to the<br />

risk <strong>of</strong> the homogenization <strong>of</strong> urban floras (La Sorte, McK<strong>in</strong>ney, &<br />

Pyˇsek, 2007), the pool <strong>of</strong> plant species that are cultivated <strong>in</strong> tropical<br />

gardens and <strong>parks</strong> can also be subjected to homogenization.<br />

A trend toward <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly standardized plant use and design <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>green</strong> elements can also endanger the dist<strong>in</strong>ctiveness <strong>of</strong> local flora<br />

(Ignatieva, 2010). Thus, it is challeng<strong>in</strong>g to identify the set <strong>of</strong> plant<br />

species that is typical <strong>of</strong> the <strong>colonial</strong> park design.<br />

This study focuses on <strong>Bandung</strong> <strong>in</strong> Westjava, Indonesia, a <strong>colonial</strong><br />

city established by Dutch settlers at the end <strong>of</strong> the 19th century.

In the 1920s, <strong>Bandung</strong> was slated to become the new <strong>colonial</strong><br />

capital and as a result experienced a rise <strong>in</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>habitants<br />

demand<strong>in</strong>g more controlled expansion <strong>of</strong> settlement areas; <strong>in</strong><br />

response, <strong>colonial</strong> planners such as Thomas Karsten and Macla<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Pont adopted western design styles to some extent for city plann<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and architecture. Yet, Karsten was also well aware <strong>of</strong> the traditional<br />

character <strong>of</strong> places when evaluat<strong>in</strong>g their potential for city<br />

plann<strong>in</strong>g and urban <strong>green</strong><strong>in</strong>g (Cobban, 1992); this was particularly<br />

true for vernacular architecture, which provides harmony between<br />

a build<strong>in</strong>g and its surround<strong>in</strong>g landscape (Jessup, 1985). As a city<br />

beautification movement <strong>in</strong> the 1930s, Bandoeng Vooruit proposed<br />

publicly accessible <strong>green</strong> areas and created aesthetically pleasant<br />

recreation sites, which could be used as research and education<br />

places, expos<strong>in</strong>g tropical flora and natural cycles (Kunto, 1986).<br />

<strong>Bandung</strong> <strong>of</strong>fers an excellent opportunity to shed light on the pr<strong>in</strong>ciples<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> plant use for urban <strong>parks</strong> because (a) conceptual<br />

ideas on the use <strong>of</strong> <strong>plants</strong> are well documented (e.g., Hendriks,<br />

1940), (b) an array <strong>of</strong> <strong>parks</strong> that had been established dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

<strong>colonial</strong> era <strong>in</strong> Indonesia (1812–1942) still exist <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>, and (c)<br />

several <strong>parks</strong> have been subsequently added with likely contrast<strong>in</strong>g<br />

post-<strong>colonial</strong> plant use. Hence, the vary<strong>in</strong>g use <strong>of</strong> species can be<br />

analyzed over a period <strong>of</strong> almost 100 years. <strong>The</strong> results are anticipated<br />

to be useful for better understand<strong>in</strong>g the important features<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>green</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> <strong>heritage</strong>; furthermore, the results can serve<br />

as a stimulus for both the contemporary management and future<br />

development <strong>of</strong> <strong>green</strong> spaces from the <strong>colonial</strong> epoch.<br />

However, the extent to which the <strong>in</strong>itial species selection for<br />

<strong>colonial</strong> <strong>parks</strong> really reflects the conceptual ideas <strong>of</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> planners<br />

regard<strong>in</strong>g plant use rema<strong>in</strong>s an open question. It also rema<strong>in</strong>s<br />

unclear whether the species that were proposed by planners <strong>in</strong> the<br />

<strong>colonial</strong> period still occur <strong>in</strong> the <strong>parks</strong> or were replaced by other<br />

species. Hence, recommendations on the plant use <strong>in</strong> conceptual<br />

publications on the design <strong>of</strong> <strong>green</strong> structures <strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong><br />

were first analyzed. Next, the species pool <strong>of</strong> planted trees, shrubs<br />

and palms <strong>in</strong> differently aged <strong>colonial</strong> and post-<strong>colonial</strong> <strong>parks</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Bandung</strong> were analyzed to test the hypothesis that remnants <strong>of</strong><br />

historically recommended species are still present <strong>in</strong> the <strong>colonial</strong><br />

<strong>parks</strong> and thus contribute to their local identity. <strong>The</strong> roles <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduced<br />

and native species <strong>in</strong> the conceptual papers and the actual<br />

species composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>’s <strong>parks</strong> are then analyzed. As conceptual<br />

papers from <strong>colonial</strong> times also claim the use <strong>of</strong> local species<br />

(Bandoeng Vooruit, 1934; Hendriks, 1940), it is anticipated that<br />

older <strong>parks</strong> still <strong>in</strong>clude species from the local Javanese flora, while<br />

younger <strong>parks</strong> show an <strong>in</strong>creased percentage <strong>of</strong> exotic species,<br />

which do not necessarily correspond to the formerly recommended<br />

woody species assemblages. <strong>The</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g research questions are<br />

used to clarify the local identity <strong>of</strong> the city: (a) which tree, shrub<br />

and palm species were recommended <strong>in</strong> early conceptual papers<br />

and for what purposes; (b) how many <strong>of</strong> these are elements <strong>of</strong> the<br />

local and native Javanese flora and how many were non-native;<br />

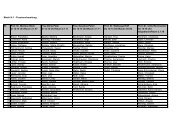

Table 1<br />

Attributes <strong>of</strong> the 10 <strong>parks</strong> <strong>in</strong>vestigated <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong> (see Fig. 1 for their locations).<br />

Park Year <strong>of</strong><br />

park<br />

open<strong>in</strong>g<br />

S. Abendroth et al. / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 106 (2012) 12– 22 13<br />

Age class Estimated age<br />

s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

reconstruction<br />

(c) which <strong>of</strong> these species still occur <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>’s <strong>parks</strong>; and (d) to<br />

what extent do the ages <strong>of</strong> the <strong>parks</strong> affect the species composition?<br />

2. Materials and methods<br />

2.1. Study area<br />

<strong>The</strong> greater <strong>Bandung</strong> area, which is 180 km southeast <strong>of</strong> Jakarta,<br />

is located <strong>in</strong> a large <strong>in</strong>tramontane bas<strong>in</strong> and surrounded by volcanic<br />

highlands (van der Kaars & Dam, 1995). Situated with<strong>in</strong><br />

the equatorial climate zone with dry and ra<strong>in</strong>y seasons, <strong>Bandung</strong><br />

has an average annual ra<strong>in</strong>fall <strong>of</strong> 1700 mm and a mean annual<br />

temperature <strong>of</strong> approximately 24 ◦ C (IWACO-WASECO, 1991). <strong>The</strong><br />

surround<strong>in</strong>g remnant montane forests still possess high numbers<br />

<strong>of</strong> plant species (van Steenis, 2006; Yamada, 1976) and underl<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Indonesia’s status as a hotspot for biodiversity (Sodhi & Brook,<br />

2006). <strong>The</strong> altitude varies from 700 m <strong>in</strong> the southern parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong><br />

to 1300 m <strong>in</strong> the northern city area. <strong>The</strong> montane climate<br />

<strong>in</strong> the Priangan Mounta<strong>in</strong>s corresponded well with the demands<br />

<strong>of</strong> European colonists for good liv<strong>in</strong>g conditions. With <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istrative duties and plans to relocate the national capital to<br />

<strong>Bandung</strong>, a city expansion was planned for the northern part <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong><br />

from the 1920s onward, and the idea to apply the garden city<br />

concept emerged (Karsten, 1920, cf. Siregar, 1990). Atta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g city<br />

status <strong>in</strong> 1906, <strong>Bandung</strong> had plenty <strong>of</strong> <strong>green</strong> areas that covered 87%<br />

and 54% <strong>of</strong> the total municipal area <strong>in</strong> 1906 and 1931, respectively<br />

(Akbar & Pribadi, 1993). In 2004, the area <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Bandung</strong> Municipality<br />

was 16,700 ha, harbor<strong>in</strong>g more than 2.7 million people. Until<br />

this date, the proportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>green</strong> spaces conspicuously decreased<br />

to 1.45% <strong>of</strong> the city area (Pemer<strong>in</strong>tah Kota <strong>Bandung</strong>, 2004). While<br />

all <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>vestigated <strong>parks</strong> rema<strong>in</strong> at their orig<strong>in</strong>al location and<br />

size, the proportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>green</strong> spaces decreased due to an <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

<strong>in</strong> city area.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>’s <strong>parks</strong> were created <strong>in</strong> the period between<br />

1920 and 1930 follow<strong>in</strong>g the scheme <strong>of</strong> European city <strong>parks</strong>. In<br />

some <strong>parks</strong>, typical elements <strong>of</strong> English landscape gardens still<br />

exist, such as scattered groups or solitaires <strong>of</strong> trees, gently roll<strong>in</strong>g<br />

lawn areas, curv<strong>in</strong>g pathways and naturally contoured lakes. <strong>The</strong><br />

oldest park is Merdeka Park, which was established <strong>in</strong> 1885 by R.<br />

Teuscher, a botanist from Bogor Botanical garden. S<strong>in</strong>ce the 1950s,<br />

Tegallega Park and Westerpark are new <strong>parks</strong> that were designed as<br />

<strong>green</strong> open spaces. Between the 1950s and 1970s, a number <strong>of</strong> old<br />

<strong>parks</strong> underwent a reconstruction process, which usually <strong>in</strong>volved<br />

new plant<strong>in</strong>gs and a renam<strong>in</strong>g (see Table 1).<br />

2.2. Data collection<br />

First, the conceptual publications <strong>of</strong> Dutch city planners from<br />

the period <strong>of</strong> time between 1900 and 1950 were analyzed, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation regard<strong>in</strong>g the design <strong>of</strong> <strong>green</strong> structures, the <strong>in</strong>tended<br />

Area (ha) <strong>Woody</strong><br />

species<br />

% extant<br />

historical<br />

species<br />

% native<br />

species<br />

%<br />

non-native<br />

species<br />

Merdeka 1885 Old 125 1.3 55 25.5 40.6 59.4 21.9<br />

Ganesha 1919 Old 50 0.3 25 48.0 22.2 77.8 11.1<br />

Maluku 1919 Old 60 2.4 71 23.9 30.2 65.1 16.3<br />

Cilaki 1920 Old 90 3.3 79 20.3 31.0 66.7 9.5<br />

Pramuka 1920 Old 40 0.2 40 32.5 26.9 61.5 11.5<br />

Insul<strong>in</strong>de 1925 Intermediate 60 3.2 54 42.6 34.1 61.4 11.4<br />

Jubileum 1923–33 Intermediate 77 8.2 142 23.9 29.3 69.5 11.0<br />

St. Ursula 1932 Intermediate 78 1.2 60 29.8 26.5 61.8 12.7<br />

Tegallega 1950–70 New 6 15.5 94 38.1 36.4 70.6 5.9<br />

Westerpark 1970s New 40 0.1 21 16.7 17.6 61.7 5.9<br />

Total 35.6 244 37.8 34.0 62.7 9.0<br />

% local<br />

species

14 S. Abendroth et al. / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 106 (2012) 12– 22<br />

Fig. 1. Historical and recent areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong> with the locations <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>vestigated <strong>parks</strong>.<br />

use <strong>of</strong> woody <strong>plants</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>’s urban <strong>parks</strong> and the underly<strong>in</strong>g<br />

motivations. <strong>The</strong> major sources <strong>of</strong> historical data on plant material<br />

were the guidel<strong>in</strong>es and the species lists for city <strong>green</strong><strong>in</strong>g from<br />

Hendriks (1940). Species that were recommended by this author,<br />

are hereafter referred to as “historical species”. For these species<br />

and all <strong>of</strong> the other species that were recorded <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>’s <strong>parks</strong>,<br />

a database with <strong>in</strong>formation on the time period <strong>of</strong> the species’<br />

<strong>in</strong>troductions to Java was established based on species lists from<br />

the Bogor Botanical Garden (Blume, 1825; Heyne, 1922; Teysmann<br />

& B<strong>in</strong>nendjik, 1866), city floras (Backer, 1907) and garden literature<br />

from the post-<strong>colonial</strong> period (Bruggeman, 1948; van der Pijl,<br />

1950).<br />

As <strong>in</strong> other studies <strong>in</strong> Bangalore (Nagendra & Gopal, 2010) or Beij<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(Weifeng, Zhiyum, Xuesong, & Xiaoke, 2006), it was anticipated<br />

that the different ages <strong>of</strong> the <strong>parks</strong> reflect possibly vary<strong>in</strong>g trends<br />

<strong>in</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> woody species. All large <strong>parks</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong> that are situated<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the 1938 historical city boundaries and cover a total<br />

area <strong>of</strong> 36 ha (Fig. 1; see Kunto, 1986 for a description <strong>of</strong> the <strong>parks</strong>)<br />

were sampled. Each <strong>of</strong> these 10 <strong>parks</strong> was attributed to one <strong>of</strong> three<br />

establishment time periods: ‘old <strong>parks</strong>’ (prior to 1925), ‘<strong>in</strong>termediate<br />

<strong>parks</strong>’ (1925–1940) and post-<strong>colonial</strong> ‘new <strong>parks</strong>’ (s<strong>in</strong>ce 1950),<br />

as listed <strong>in</strong> Table 1.<br />

In each park, the species composition <strong>of</strong> the cultivated trees,<br />

shrubs and palms between August and October 2009 was analyzed<br />

at two scales. First, at the park scale, the overall species number<br />

<strong>of</strong> each park was recorded by <strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>g the entire park area<br />

with its species composition. Further analyses were performed at<br />

a plot scale. Us<strong>in</strong>g aerial pictures, the patches covered with woody<br />

vegetation were identified <strong>in</strong> each park and a 20 m × 20 m grid was<br />

overlaid on the pictures. Cells that were chosen randomly out <strong>of</strong><br />

the grid were selected as sample plots, with 71 total sample plots<br />

for the 10 <strong>parks</strong>.<br />

Depend<strong>in</strong>g on the size <strong>of</strong> the <strong>parks</strong> and the woody areas with<strong>in</strong><br />

the <strong>parks</strong>, the number <strong>of</strong> plots per park ranged from 2 to 17.<br />

With<strong>in</strong> these plots, all planted trees, shrubs and palms with a height<br />

>0.90 m and a diameter breast height (DBH) >0.01 m were sampled.<br />

Historical species that occurred <strong>in</strong> the recent species composition<br />

were regarded as extant historical species, while all other<br />

species were regarded as recent species. <strong>The</strong> nomenclature followed<br />

that <strong>of</strong> Backer and van den Br<strong>in</strong>k (1965–68). Information<br />

on the native range <strong>of</strong> the species was extracted from the same<br />

sources and grouped <strong>in</strong>to the same categories as those <strong>in</strong> Weber<br />

(2003). After human disturbances and modifications, Java’s natural<br />

forests only cover 8% <strong>of</strong> the island (Smiet, 1990); thus, the<br />

rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g elements <strong>of</strong> the surround<strong>in</strong>g forests <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong> played<br />

important roles <strong>in</strong> this study regard<strong>in</strong>g historical plant use and the<br />

recommended species pool from local surround<strong>in</strong>gs. In the 19th<br />

century, the curators from the Bogor and Cibodas Botanical Gardens<br />

had already realized the potential <strong>of</strong> forests on Java to explore<br />

their species assemblage as a natural basel<strong>in</strong>e. Species that naturally<br />

occur on Java were grouped as ‘native species’. As a subset <strong>of</strong><br />

this group, species from the Javanese coll<strong>in</strong>e and sub-montane altitud<strong>in</strong>al<br />

zones (van Steenis, 2006) were addressed as ‘local species’.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se are species that occur with<strong>in</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> 500–1500 m asl and<br />

were thus supposed to represent the vegetation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>’s local<br />

surround<strong>in</strong>g forests (Haberlandt, 1893).<br />

Each woody species was assigned to one or more <strong>of</strong> the three<br />

functional groups based on its potential use for (a) ornamentation,<br />

(b) food or medic<strong>in</strong>e, and (c) timber or construction, based on historical<br />

references (Bandoeng Vooruit, 1934; Hendriks, 1940; van<br />

der Pijl, 1950) or more recent work (Ch<strong>in</strong>, 2003; Hanum & van der<br />

Maesen, 1997; PT. Eisai Indonesia, 1995).<br />

<strong>The</strong> species importance (SI) measure, which is the sum <strong>of</strong> relative<br />

abundance (RA) and relative dom<strong>in</strong>ance (RD) <strong>of</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle species<br />

(McPherson & Rowntree, 1987; Welch 1994), was calculated for the<br />

species with<strong>in</strong> all <strong>of</strong> the plots. In this study, relative abundance (RA)<br />

is represented by the proportion <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>dividual species to the total<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual numbers <strong>in</strong> all <strong>of</strong> the plots belong<strong>in</strong>g to a respective<br />

park age category. Relative dom<strong>in</strong>ance (RD) was calculated from<br />

the percentage <strong>of</strong> the basal area <strong>of</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle species to the total basal<br />

area <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> all <strong>of</strong> the plots belong<strong>in</strong>g to a respective<br />

park age category.<br />

In conclusion, this study divided and compared the follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

specific species categories. (1) Species were subdivided <strong>in</strong>to life<br />

forms based on their status: (a) native, (b) local, or (c) non-native;<br />

(2) Species were subdivided <strong>in</strong>to life forms based on their historical<br />

usage: (a) historical species (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g extant historical) or<br />

(b) recent species; (3) Depend<strong>in</strong>g on their purpose, species were<br />

subdivided <strong>in</strong>to (a) ornamentation, (b) food or medic<strong>in</strong>e, or (c)<br />

timber or construction categories; and f<strong>in</strong>ally, the three park age<br />

classes were categorized as (a) new, (b) <strong>in</strong>termediate, or (c) old<br />

<strong>parks</strong>.

S. Abendroth et al. / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 106 (2012) 12– 22 15<br />

Table 2<br />

Overview <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> woody species, their life forms and statuses <strong>in</strong> historical and recent species compositions <strong>of</strong> the <strong>parks</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>. Local species are considered<br />

as a subset <strong>of</strong> native species. Column A <strong>in</strong>dicates species recommended by Hendriks (1940) and columns B and C refer to species detected on the park scale (10 <strong>parks</strong>).<br />

Species groups with respect to their historical usage Historical species Recent species<br />

A B C<br />

Life form Status Total historical species Extant historical species<br />

Trees Native, non-local 22 15 40<br />

Native, local 16 12 3<br />

Non-native 37 31 69<br />

Unknown 3 1 4<br />

Shrubs and palms Native non-local 4 2 5<br />

Native, local 2 2 4<br />

Non-native 25 17 36<br />

Unknown 2 2 1<br />

Total species 111 82 162<br />

Total non-native (%) 55.9 58.5 64.8<br />

Total native (%) (local and non-local) 39.6 37.8 32.1<br />

Total local (%) 16.2 17.1 4.3<br />

2.3. Statistical analyses<br />

To assess whether specific species categories differ <strong>in</strong> their proportions<br />

<strong>of</strong> non-native species, a chi-squared test was used on the<br />

distribution <strong>of</strong> native/non-native statuses with<strong>in</strong> the categories <strong>of</strong><br />

historical usage and species’ purpose. <strong>The</strong> historical usage analysis<br />

was performed separately for each life form.<br />

To explore whether elements <strong>of</strong> the local forest zone contribute<br />

to the extant historical species, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient<br />

between the number <strong>of</strong> extant historical species and the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> local species with<strong>in</strong> the 71 sample plots was calculated.<br />

<strong>The</strong> correlation between park size and proportion <strong>of</strong> native and<br />

local species with<strong>in</strong> the 10 <strong>parks</strong> was also calculated. To explore<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> park age on recent species composition, Spearman’s rank<br />

correlation coefficient between the respective park ages and the<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> specific species categories was calculated. Proportions<br />

were calculated based on both the species importance (SI)<br />

measure and the species richness.<br />

Next, differences between age class and species categories were<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigated us<strong>in</strong>g two-way analysis <strong>of</strong> variance (ANOVA). To test<br />

the null hypothesis <strong>of</strong> no significant differences <strong>in</strong> the species compositions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the three age classes, the proportion <strong>of</strong> specific species<br />

categories was used as the explanatory variable and the age class <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>parks</strong> was used as the predictor. Significant differences <strong>in</strong> the<br />

dependent variables among the three age classes were revealed<br />

by a Post-Hoc Tukey’s test. Prior to the analysis, the proportions<br />

were transformed by arcs<strong>in</strong>-transformation to stabilize the variances.<br />

To trace the differences <strong>in</strong> the woody species compositions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>vestigated <strong>parks</strong>, a cluster analysis with Euclidean distance<br />

measure was applied, and Ward’s method was applied to<br />

the species data at the park level. Parks were grouped <strong>in</strong>to clusters<br />

<strong>of</strong> similar species composition by a visual <strong>in</strong>spection <strong>of</strong> the<br />

result<strong>in</strong>g cluster dendrogram. To test whether particular species<br />

were related to a particular park cluster, an <strong>in</strong>dicator species analysis<br />

was used (Dufrene & Legendre, 1997); this analysis took the<br />

frequencies <strong>of</strong> the entire species composition with<strong>in</strong> the 10 <strong>parks</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>to account. <strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpreted computer language ‘R’ version 2.10.0<br />

(R Development Core Team, 2009) was used for all <strong>of</strong> the statistical<br />

analyses, and PC-ORD version 4.0 (McCune & Mefford, 1999) was<br />

used for the <strong>in</strong>dicator species analysis.<br />

3. Results<br />

3.1. Historical plant use <strong>in</strong> the <strong>colonial</strong> <strong>parks</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong><br />

3.1.1. Species cultivated <strong>in</strong> the <strong>colonial</strong> period<br />

City planners and gardeners <strong>in</strong> Indonesia can look back on<br />

a flourish<strong>in</strong>g period <strong>of</strong> plant <strong>in</strong>troduction and cultivation. <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> historical species <strong>in</strong> Indonesia can be traced back<br />

from the 9th century, dur<strong>in</strong>g which ornamental flowers were displayed<br />

on the engrav<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> the Borobudur Temples (Sarwono,<br />

1988). With the arrival <strong>of</strong> Portuguese explorers and seamen <strong>in</strong><br />

1511, various <strong>plants</strong>, especially South American species, were cultivated<br />

(Shelton and Brewbaker, 1994). S<strong>in</strong>ce the open<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Bogor Botanical Garden <strong>in</strong> 1817 and the Cibodas Botanical Garden<br />

<strong>in</strong> the 1830s, centers <strong>of</strong> horticulture were established. This underl<strong>in</strong>es<br />

the importance <strong>of</strong> botanical gardens <strong>in</strong> the <strong>colonial</strong> era, dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

which garden<strong>in</strong>g became a leisure pursuit, especially <strong>in</strong> the tropics<br />

(Heywood, 2010; Warren, 1991).<br />

In the guidel<strong>in</strong>es from Hendriks (1940), 111 historical species<br />

are mentioned, conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 78 tree species and 33 shrub and palm<br />

species. Table 2 shows the life forms and statuses <strong>of</strong> these historical<br />

species <strong>in</strong> comparison with the 2009 plant composition. As<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicated <strong>in</strong> column A, the total historical species are comprised<br />

<strong>of</strong> 40% native species and 56% non-native species. If only trees are<br />

considered, native and non-native species each contribute 50% <strong>of</strong><br />

the historical species, whereas non-native species are clearly dom<strong>in</strong>ant<br />

<strong>in</strong> the shrubs and palms. Historical references describe 6 native<br />

shrub and palm species and 25 non-native shrub and palm species.<br />

Approximately 16% <strong>of</strong> the historical species are local elements<br />

<strong>of</strong> the mounta<strong>in</strong> vegetation <strong>in</strong> Java. Other native but non-local<br />

species orig<strong>in</strong>ate from lowland ra<strong>in</strong>forest and Java’s coastal regions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> highest numbers <strong>of</strong> local species are contributed by trees (16<br />

species), followed by palms (2).<br />

3.1.2. Orig<strong>in</strong> and purposes <strong>of</strong> historical species<br />

In particular, shad<strong>in</strong>g trees and colorful ornamental species<br />

were requested <strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong> (Hendriks, 1940; van der Pijl,<br />

1950). From the historical species pool (see Table 3), most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced species come from tropical America (21 species), followed<br />

by Southeast Asia (19) and tropical Africa (9). <strong>The</strong> assignment<br />

<strong>of</strong> the historical species to different (potential) purposes shows that<br />

the non-native species dom<strong>in</strong>ate the group <strong>of</strong> ornamentals. As primarily<br />

<strong>in</strong>tended <strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> concepts, only 18 native species with<br />

high ornamental value were historically recommended. Besides<br />

the 18 species from tropical America, 14 species from the wider<br />

Southeast Asia region are <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the ornamental composition.<br />

Nevertheless, the non-native ornamental species dom<strong>in</strong>ate with<br />

nearly 72% when consider<strong>in</strong>g all historical species. <strong>The</strong> share <strong>of</strong> historical<br />

species with medic<strong>in</strong>al and diet value is noteworthy, which<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong>clude 20 native and local species, such as Elaeocarpus<br />

grandiflorus, Syzygium polyanthum or Cananga odorata. Economic<br />

benefits are provided by the species used for timber production,<br />

such as P<strong>in</strong>us merkusii and Swietenia macrophylla; the latter was also<br />

recommended for <strong>parks</strong> as fast-grow<strong>in</strong>g shelter trees (Hendriks,<br />

1940). Compared to the ornamental species, the native species

16 S. Abendroth et al. / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 106 (2012) 12– 22<br />

Table 3<br />

Areas <strong>of</strong> species orig<strong>in</strong> and the number <strong>of</strong> woody species occurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the <strong>parks</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>. Data are shown for species that were recommended by <strong>colonial</strong> planners <strong>in</strong> 1940<br />

(‘historical species’) and recent species that occur <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>’s <strong>parks</strong> <strong>in</strong> 2009. In addition, potential purposes that can be assigned to these species are shown. One species<br />

can fulfill more than one purpose.<br />

Orig<strong>in</strong> Historical species<br />

(n = 111)<br />

Recent species<br />

(n = 162)<br />

Species groups <strong>in</strong> regard to their purposes,<br />

historical species/recent species<br />

Ornamental<br />

(n = 71)/(n = 102)<br />

Food and<br />

medic<strong>in</strong>e<br />

(n = 50)/(n = 90)<br />

Timber and<br />

construction<br />

(n = 33)/(n = 51)<br />

Native (non-local) 26 45 12 24 7 31 8 23<br />

Native (local) 18 7 6 5 13 3 11 1<br />

Tropical SE Asia 19 29 14 15 13 19 7 13<br />

Temperate Asia 7 13 6 10 3 4 0 0<br />

Australia 3 11 3 9 2 1 1 3<br />

Tropical Africa 10 15 8 11 4 7 2 3<br />

S Europe 2 0 2 0 1 0 0 0<br />

Tropical America 21 37 18 28 4 21 4 7<br />

Unknown 5 5 2 0 3 4 0 1<br />

Total non-native (%) 55.9 64.8 71.8 71.6 54.0 57.8 42.4 51.0<br />

Total native (%) (local and non-local) 39.6 32.1 25.4 28.4 40.0 37.8 57.6 47.1<br />

Total local (%) 16.2 4.3 8.5 4.9 26.0 3.3 33.3 2.0<br />

make up a larger share <strong>of</strong> the species that were historically recommended<br />

for food and medical purposes (54.0%) and timber and<br />

construction (42.4%).<br />

Although many current non-native species were also available<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> Indonesia (Blume 1825; Teysmann & B<strong>in</strong>nendjik, 1866),<br />

<strong>colonial</strong> planners did not recommend these species. Thus, criteria<br />

other than availability, such as miss<strong>in</strong>g site adaptation or usability<br />

for ornamentation or shad<strong>in</strong>g, were likely decisive for their former<br />

limited use.<br />

Ornamental species like Hibiscus rosa-s<strong>in</strong>ensis are already displayed<br />

on the ancient reliefs <strong>of</strong> the Borobodur Temples. Another<br />

species <strong>in</strong>troduced to Southeast Asia prior to 1817 is Leucaena<br />

leucocephala, which was recommended by Hendriks (1940) for<br />

shelter and forage. Historical species <strong>in</strong>troduced after 1900 <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

Jacaranda filicifolia, Galphimia gracilis or Cassia multijuga, which<br />

were both ornamentals from tropical America (Fig. 2).<br />

3.2. Recent species composition and distribution<br />

In the 10 <strong>parks</strong> that were surveyed, 244 woody species were<br />

recorded <strong>in</strong> total, belong<strong>in</strong>g to 181 genera and 62 families. <strong>The</strong><br />

most dom<strong>in</strong>ant families were Legum<strong>in</strong>osaceae (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Caesalp<strong>in</strong>aceae,<br />

Mimosaceae, Fabaceae) with 38 species, Arecaceae<br />

(23 species) and Euphorbiaceae (15 species). Of all <strong>of</strong> the woody<br />

park species, 175 (72%) were trees, 45 (18%) were shrubs and 24<br />

(10%) were palm species. In the sample plots, 70% <strong>of</strong> the total<br />

park species were recorded, with a total <strong>of</strong> 1265 <strong>in</strong>dividuals. <strong>The</strong><br />

most abundant species is the <strong>in</strong>troduced broad-leaved mahogany<br />

7<br />

4<br />

9<br />

before 1817<br />

25<br />

20<br />

41<br />

1817-1850<br />

26<br />

22<br />

34<br />

1850-1900<br />

9<br />

5<br />

21<br />

after 1900<br />

historical species n= 67<br />

extant historical species n =51<br />

recent species n =105<br />

Fig. 2. Time period <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduction and the numbers <strong>of</strong> non-native woody species<br />

that were recommended by <strong>colonial</strong> planners (historical species), extant historical<br />

species and recent species that occur <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>’s <strong>parks</strong>.<br />

(Swietenia macrophylla), followed by the Indonesian bay leaf (Syzygium<br />

polyanthum), which is the most abundant native species (see<br />

Tables 4 and 5).<br />

Approximately three quarters (74%) <strong>of</strong> the 111 historical species<br />

still occur <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>’s <strong>parks</strong>. <strong>The</strong>se represent 38% <strong>of</strong> all recent<br />

woody park species. At the plot scale, 55% <strong>of</strong> the historical species<br />

were documented. Ganesha Park and Insul<strong>in</strong>de Park showed the<br />

highest share (more than 40%) <strong>of</strong> extant historical species (see<br />

Table 1).<br />

Historical sources stated that larger <strong>parks</strong> can be equipped with<br />

large-grow<strong>in</strong>g and canopy<strong>in</strong>g tree species, which symbolize the<br />

natural surround<strong>in</strong>g forest vegetation <strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> Java (Hendriks,<br />

1940). For the 10 <strong>parks</strong>, Spearman’s rank correlation proved that<br />

there is a significant correlation between the park area and the<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> native species (p-value = 0.03) while no significant<br />

correlation was found for local species (p > 0.1). Furthermore, the<br />

park <strong>in</strong>vestigation showed that 9% <strong>of</strong> the local species are present<br />

among the entire 244 park species. At plot scale, 12% <strong>of</strong> local<br />

species could be found. This proportion varied among the 10 <strong>parks</strong><br />

from 5.9% <strong>in</strong> the young <strong>parks</strong> to 21.9% <strong>in</strong> the oldest park (see<br />

Table 1). Remarkable native ornamental species with attractive<br />

flowers and fragrances are Schima wallichii, Alt<strong>in</strong>gia excelsa, Cananga<br />

odorata, C<strong>in</strong>namonum spec., Elaeocarpus grandiflorus, and Lagerstroemia<br />

speciosa as tree species, and Ixora javanica, Mussaenda<br />

frondosa, Clerodendron paniculata or Tallauma candollii represent<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the low number <strong>of</strong> shrub species (see Table 2).<br />

3.3. Differences between the historical and the recent species<br />

compositions<br />

Fig. 3 <strong>in</strong>dicates that a significant disparity exists <strong>in</strong> the shares<br />

<strong>of</strong> native species between the historical and the recent tree species<br />

(chi-squared test, p-value < 0.001). <strong>The</strong> historical plant design recommended<br />

native and non-native tree species equally, whereas<br />

non-native species prevail with over 80% <strong>of</strong> the recent tree composition.<br />

This is primarily based on the fact that another 69 non-native<br />

tree species and 40 native tree species were present <strong>in</strong> 2009 (see<br />

Table 2). Local and native shrubs and palms, which played only a<br />

small role <strong>in</strong> the historical recommendations, show an <strong>in</strong>crease for<br />

recent species; however, their species numbers are much lower<br />

than those <strong>of</strong> non-native species. <strong>The</strong> native statuses <strong>of</strong> historical<br />

and recent shrub and palm species showed no significant differences<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g the chi-squared test (p-value 0.9), and the non-native<br />

species dom<strong>in</strong>ate with<strong>in</strong> both categories at approximately 80% (see<br />

Fig. 3).

S. Abendroth et al. / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 106 (2012) 12– 22 17<br />

Table 4<br />

Size class distribution <strong>of</strong> the most abundant tree species with<strong>in</strong> 71 plots <strong>in</strong> the <strong>parks</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong> (n = number <strong>of</strong> sampled <strong>in</strong>dividuals).<br />

Species Species percentage <strong>of</strong> DBH classes (m) n<br />

0.9<br />

Swietenia macrophylla 1,3 39.6 15.4 8.8 27.5 8.8 0.0 91<br />

Syzygium polyanthum 1,2,4 47.4 33.3 5.3 14.0 0.0 0.0 57<br />

P<strong>in</strong>us merkusii 1,3 2.3 25.6 23.3 48.8 0.0 0.0 43<br />

Bauh<strong>in</strong>ia purpurea & variegata 1,3 12.5 27.5 42.5 17.5 0.0 0.0 40<br />

Elaeocarpus sphaericus 1,2,4 23.7 10.5 5.3 13.2 31.6 15.8 38<br />

Filicium decicpiens 1,3 7.9 7.9 18.4 44.7 18.4 2.6 38<br />

Delonix regia 1,3 2.8 19.4 5.6 44.4 22.2 5.6 36<br />

Pterocarpus <strong>in</strong>dicus 1,2 0.0 15.6 9.4 25.0 12.5 37.5 32<br />

Spathodea campanulata 1,3 4.0 28.0 8.0 16.0 16.0 28.0 25<br />

Lagerstroemia speciosa 1,2 0.0 16.7 41.7 25.0 12.5 4.2 24<br />

Mimusops elengi 1,2 30.0 5.0 15.0 25.0 20.0 5.0 20<br />

Ficus benjam<strong>in</strong>a 1,2,4 0.0 12.5 0.0 6.3 31.3 50.0 16<br />

1 Historical.<br />

2 Native.<br />

3 Non-native.<br />

4 Local.<br />

Furthermore, the analysis <strong>of</strong> the extant historical species<br />

showed that species from local mounta<strong>in</strong> ranges are an <strong>in</strong>tegral<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the historical species assemblage. A significant correlation<br />

between the number <strong>of</strong> historical species and the number <strong>of</strong> local<br />

species with<strong>in</strong> sample plots could be detected (Spearman’s correlation<br />

coefficient 0.34, p-value 0.0025). Seven additional local species<br />

are detected that are not historically recommended but contribute<br />

to the recent species pool (see Table 2), which contrast<strong>in</strong>gly obta<strong>in</strong>s<br />

4.3% local species.<br />

When compar<strong>in</strong>g historical and recent species based on their<br />

potential purposes, the number <strong>of</strong> species with values for food<br />

or medic<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> particular was found to have <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> the<br />

recent species composition. Here, auxiliary species like Artocarpus<br />

spp. (Breadfruit), Nephelium lappaceum (Rambutan) or Syzygium<br />

aqueum (Water Apple) represent a broad range <strong>of</strong> fruit trees (see<br />

Table 5).<br />

3.4. Influence <strong>of</strong> park age on species composition<br />

Table 6 illustrates the relations between park age and species<br />

composition. While the Species Importance and the richness <strong>of</strong><br />

recent species were not correlated with park age, these variables<br />

Table 5<br />

Most important woody species sampled <strong>in</strong> the 71 plots with<strong>in</strong> the 10 <strong>parks</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong> with their orig<strong>in</strong>s, life forms and potential purposes. <strong>The</strong> species list <strong>in</strong>cludes species<br />

that collectively add up to at least 75% <strong>of</strong> all <strong>in</strong>dividuals (n = 942) and show a relative abundance >10%.<br />

Species Family Orig<strong>in</strong> Life-form Purpose Relative<br />

abundance<br />

(n = 71)<br />

Swietenia macrophylla1 Meliaceae Tropical America Tree, deciduous Timber, medic<strong>in</strong>e 43.7 9.3<br />

Pterocarpus <strong>in</strong>dicus1 Fabaceae Tropical Asia, Java Tree, deciduous Timber, medic<strong>in</strong>e 23.9 3.4<br />

Elaeocarpus sphaericus1,4 Elaeocarpaceae Tropical Asia, Java Tree, ever<strong>green</strong> Medic<strong>in</strong>e 25.4 4.0<br />

Delonix regia1 Caesalp<strong>in</strong>aceae Tropical Africa Tree, deciduous Ornamental 28.2 3.8<br />

Filicium decipiens1 Sap<strong>in</strong>daceae Tropical Asia Tree, ever<strong>green</strong> Ornamental 28.2 4.0<br />

P<strong>in</strong>us merkusii1 P<strong>in</strong>aceae Tropical Asia Tree, ever<strong>green</strong> Timber 19.7 4.6<br />

Spathodea campanulata1 Bignoniaceae Tropical Africa Tree, deciduous Ornamental 22.5 2.7<br />

Syzygium polyanthum1,4 Myrtaceae Tropical Asia, Java Tree, deciduous Medic<strong>in</strong>e, timber 29.6 5.7<br />

Bauh<strong>in</strong>ia purpurea & variegata1 Caesalp<strong>in</strong>aceae Tropical Asia Tree, deciduous Ornamental 10.0 4.2<br />

Dypsis lutescens1 Palmae Tropical Africa Palm Ornamental 14.1 2.1<br />

Lagerstroemia speciosa1 Lythraceae Tropical Asia, Java Tree, deciduous Ornamental,<br />

medic<strong>in</strong>e,<br />

construction<br />

15.5 2.5<br />

Roystonea regia1 Palmae Tropical America Palm Ornamental 15.5 1.9<br />

Ficus benjam<strong>in</strong>a1,4 Moraceae Tropical Asia, Java Tree, ever<strong>green</strong> Ornamental,<br />

medic<strong>in</strong>e<br />

19.7 1.7<br />

Mimusops elengi1 Sapotaceae Tropical Asia, Java Tree, ever<strong>green</strong> Ornamental,<br />

medic<strong>in</strong>e, timber<br />

11.3 2.1<br />

Mangifera <strong>in</strong>dica1 Anacardiaceae Unknown, trop. Asia Tree, ever<strong>green</strong> Food, medic<strong>in</strong>e 19.7 3.2<br />

Erythr<strong>in</strong>a crista-galli Fabaceae Tropical America Tree, deciduous Ornamental 16.9 2.3<br />

Artocarpus heterophyllus Moraceae Tropical Asia Tree, ever<strong>green</strong> Food, medic<strong>in</strong>e,<br />

timber<br />

22.5 3.3<br />

Citrus grandis Rutaceae Tropical Asia Tree, ever<strong>green</strong> Food, medic<strong>in</strong>e 10.0 1.3<br />

Samanea saman1 Mimosaceae Tropical America Tree, deciduous Ornamental,<br />

timber<br />

12.7 1.3<br />

Acalypha siamensis1 Euphorbiaceae Tropical Asia Shrub, ever<strong>green</strong> Ornamental 12.7 1.9<br />

Bounga<strong>in</strong>villea sp. 1 Nyctag<strong>in</strong>aceae Tropical America Shrub, ever<strong>green</strong> Ornamental 19.7 2.0<br />

Artocarpus altilis Moraceae Tropical Asia Tree, ever<strong>green</strong> Food 16.9 1.9<br />

Nephelium lappaceum Sap<strong>in</strong>daceae Tropical Asia, Java Tree, ever<strong>green</strong> Food 14.1 2.9<br />

Caesalp<strong>in</strong>a pulcherrima1 Caesalp<strong>in</strong>aceae Tropical America Shrub, ever<strong>green</strong> Ornamental 11.3 1.9<br />

Syzygium aqueum Myrtaceae Tropical Asia, Java Tree, ever<strong>green</strong> Food, ornamental,<br />

medic<strong>in</strong>e<br />

15.5 1.5<br />

1 Historical species.<br />

4 Local species.<br />

Frequency<br />

(n = 942)

18 S. Abendroth et al. / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 106 (2012) 12– 22<br />

49.4<br />

21.3<br />

29.3<br />

trees<br />

80.6 81.0 80.0<br />

6.5 9.5 8.9<br />

12.9 9.5 11.1<br />

shrubs &<br />

palms<br />

historical species<br />

trees<br />

recent species<br />

shrubs &<br />

palms<br />

non-native<br />

local<br />

native<br />

Fig. 3. Status <strong>of</strong> species <strong>in</strong> regards to their historical usage. Shown are the percentages<br />

<strong>of</strong> historical species and recent species with<strong>in</strong> different life forms.<br />

significantly <strong>in</strong>creased with park age for extant historical trees.<br />

Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, non-native tree species show no correlation with<br />

park age. In the sample plots, a significant relationship between<br />

park age and the ratio <strong>of</strong> non-native shrubs is evident. Older <strong>parks</strong><br />

show higher levels <strong>of</strong> richness and species importance <strong>of</strong> nonnative<br />

shrubs compared to younger ones. <strong>The</strong> richness <strong>of</strong> local<br />

native species from the surround<strong>in</strong>g mounta<strong>in</strong> flora <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong><br />

older <strong>parks</strong>.<br />

<strong>The</strong> relations between park age and the share <strong>of</strong> different species<br />

groups were even more pronounced when <strong>parks</strong> were grouped <strong>in</strong>to<br />

three age classes (see Table 7). <strong>The</strong>re were 14, 31, and 26 sample<br />

plots for the categories <strong>of</strong> new, <strong>in</strong>termediate, and old <strong>parks</strong>,<br />

respectively. Support<strong>in</strong>g the correlative results, new <strong>parks</strong> differ<br />

significantly from old <strong>parks</strong> when consider<strong>in</strong>g the number <strong>of</strong> recent<br />

species. Fig. 4a shows that old <strong>parks</strong> accommodate more historical<br />

trees than new <strong>parks</strong>, while the difference between <strong>in</strong>termediate<br />

and old <strong>parks</strong> is not significant. Old and <strong>in</strong>termediate <strong>parks</strong> had<br />

significantly more local species than new <strong>parks</strong> (see Fig. 4).<br />

As shown <strong>in</strong> Fig. 5, old and <strong>in</strong>termediate <strong>parks</strong> have higher<br />

species importance measures (SI) than new <strong>parks</strong> for most<br />

abundant woody species. <strong>The</strong>re are three exceptions: Swietenia<br />

macrophylla, Bauh<strong>in</strong>ia div. spec. and Syzygium polyanthum prevail<br />

<strong>in</strong> newer <strong>parks</strong>. Swietenia macrophylla is the most abundant tree<br />

and clearly dom<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>in</strong> young and <strong>in</strong>termediate <strong>parks</strong>. <strong>The</strong> native<br />

species Pterocarpus <strong>in</strong>dicus and the local species Ficus benjam<strong>in</strong>a<br />

and Elaeocarpus sphaericus dom<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong> <strong>parks</strong> created between<br />

1925 and the 1930s. Native species such as Mimusops elengii or<br />

Table 6<br />

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients between park age as a predictor and specific<br />

species categories as explanatory variables with<strong>in</strong> the 71 sample plots based on the<br />

dependent variables Species Importance and richness.<br />

Explanatory variables Dependent variables<br />

Species Importance (SI) Richness<br />

Proportion <strong>of</strong> species categories <strong>in</strong> regards to their historical usage<br />

Recent species −0.19 −0.06<br />

Extant historical<br />

trees<br />

0.29 * 0.34 **<br />

Proportion <strong>of</strong> species categories <strong>in</strong> regards to their status<br />

Non-native trees −0.05 −0.02<br />

Non-native shrubs<br />

and palms<br />

0.30 * 0.31 **<br />

Local species 0.07 0.33 *<br />

* Two-tailed significance: 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05.<br />

** Two-tailed significance: p ≤ 0.01.<br />

Fig. 4. Boxplots show<strong>in</strong>g the three park age classes with the proportions <strong>of</strong> (a) extant<br />

historical tree species, based on the dependent variable species importance (SI), and<br />

(b) local species, based on the dependent variable species richness. In both figures,<br />

new <strong>parks</strong> differ significantly from <strong>in</strong>termediate and old <strong>parks</strong>.<br />

Lagerstroemia speciosa, which are rarely planted <strong>in</strong> new <strong>parks</strong>,<br />

largely dom<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong> old <strong>parks</strong>.<br />

<strong>The</strong> cluster dendrogram revealed two dist<strong>in</strong>ct groups <strong>of</strong> <strong>parks</strong><br />

accord<strong>in</strong>g to their woody species composition. <strong>The</strong> first group<br />

<strong>in</strong>cludes Jubileumpark (Zoo), Ganesha, Cilaki and St. Ursula Park,<br />

while the second cluster <strong>in</strong>cluded all <strong>of</strong> the other <strong>parks</strong>. While<br />

small branches <strong>in</strong> the second cluster <strong>in</strong>dicate a low variation <strong>in</strong><br />

the group’s species composition, the first cluster is obviously more<br />

heterogeneous <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> species composition. <strong>The</strong> first park cluster<br />

was clearly <strong>in</strong>dicated by 8 historical species and 1 recent species<br />

<strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dicator species analysis (see Table 8). <strong>The</strong> second cluster<br />

showed no significant <strong>in</strong>dicator species and is therefore only negatively<br />

characterized by the lack <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicator species from the first<br />

cluster (Fig. 6).<br />

4. Discussion<br />

Analyz<strong>in</strong>g a city’s history with its <strong>green</strong> structures provides<br />

<strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>to specific historical plant design, which, comb<strong>in</strong>ed with

S. Abendroth et al. / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 106 (2012) 12– 22 19<br />

Table 7<br />

Results <strong>of</strong> a Tukey Test, assess<strong>in</strong>g differences between old, <strong>in</strong>termediate and new <strong>parks</strong> as predictor and specific species compositions as explanatory variables with<strong>in</strong> 71<br />

sample plots based on the dependent variables Species Importance and richness.<br />

Explanatory variables Dependent variables<br />

Species Importance (SI) Richness<br />

Proportion <strong>of</strong> species categories referr<strong>in</strong>g to their<br />

historical usage<br />

Recent trees Old < new * Old < new ***<br />

Extant historical trees Intermediate > new *** old > new *** Intermediate > new *** old > new ***<br />

Proportion <strong>of</strong> species categories referr<strong>in</strong>g to their status<br />

Non-native trees Old > new *** Intermediate > new ** old > new **<br />

Non-native shrubs and palms Intermediate > new *** old > new *** Intermediate > new *** old > new ***<br />

Local species Intermediate > new Intermediate > new *** old > new ***<br />

* Two-tailed significance: 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05.<br />

** Two-tailed significance: p ≤ 0.01.<br />

*** Two-tailed significance: p ≤ 0.001.<br />

Species Importance measure (SI)<br />

18<br />

16<br />

14<br />

12<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

new <strong>parks</strong> SI=38.3<br />

<strong>in</strong>termediate <strong>parks</strong><br />

SI=56.9<br />

old <strong>parks</strong> SI=50.5<br />

Fig. 5. Most abundant tree species <strong>in</strong> the three different age categories <strong>in</strong> the <strong>parks</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>, ranked accord<strong>in</strong>g to decreas<strong>in</strong>g Species Importance (SI) measures. For each<br />

species, the SI is calculated for respective plots belong<strong>in</strong>g to the different age categories. 1 historical, 2 native, 3 non-native, 4 local species.<br />

architecture, created a unique <strong>colonial</strong> <strong>heritage</strong>. Studies on the<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>of</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> plant use for urban <strong>parks</strong> are still limited,<br />

especially for tropical regions. If available, these studies contribute<br />

to a more detailed understand<strong>in</strong>g about historical plant<strong>in</strong>g characteristics<br />

(Santos et al., 2010; Sreetheran et al., 2006). Recent<br />

research <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong> benefits from well-documented plann<strong>in</strong>g concepts<br />

and the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g historical study sites from the Dutch<br />

<strong>colonial</strong> era. Before discuss<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Bandung</strong>’s history <strong>of</strong> <strong>green</strong> spaces<br />

<strong>in</strong> more detail, the role played by colony-wide botanic gardens <strong>in</strong><br />

promot<strong>in</strong>g the use <strong>of</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> species will be clarified. Initially,<br />

the Bogor Botanical Garden served as an <strong>in</strong>troduction agent and<br />

study area for <strong>plants</strong> with domestic and medic<strong>in</strong>al purposes <strong>in</strong><br />

Javanese tradition and, from the 1850s onward, for useful <strong>plants</strong><br />

Table 8<br />

Indicator species for the first park cluster based on the <strong>in</strong>dicator species analysis (7).<br />

Species name p-Value<br />

Lagerstroemia speciosa 1 0.009<br />

Pterocarpus <strong>in</strong>dicus 1 0.014<br />

Delonix regia 1 0.019<br />

Swietenia macrophylla 1 0.019<br />

Artocarpus altilis 0.023<br />

P<strong>in</strong>us merkusii 1 0.028<br />

Bauh<strong>in</strong>ia purpurea & variegata 1 0.032<br />

Tectona grandis 1 0.036<br />

Syzygium polyanthum 1 0.047<br />

1 Historical species.<br />

with nationwide economic and agricultural purposes, such as the<br />

C<strong>in</strong>chona, C<strong>of</strong>fea or Palaquium species. An enormous <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong><br />

the number <strong>of</strong> species cultivated <strong>in</strong> the Bogor Botanical Garden<br />

was documented, with 914 species <strong>in</strong> 1923 and 2800 species <strong>in</strong><br />

1844 (Haberlandt, 1893). With the open<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the Cibodas Botanic<br />

Garden near <strong>Bandung</strong>, the <strong>in</strong>vestigation and observation <strong>of</strong> local<br />

flora was supported as part <strong>of</strong> a theoretical botany with<strong>in</strong> Java<br />

Fig. 6. Cluster dendrogram <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g the 2 major park groups <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>.

20 S. Abendroth et al. / Landscape and Urban Plann<strong>in</strong>g 106 (2012) 12– 22<br />

(Haberlandt, 1893). In <strong>colonial</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>, Dutch members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Bandung</strong> beautification movement with scientific botanical backgrounds,<br />

namely Doctors van Leeuwen and van der Pijl, were<br />

valuable patrons for the new public park models (Kunto, 1986) and<br />

contributed knowledge about surround<strong>in</strong>g local flora <strong>in</strong> the 1920s<br />

and 1930s. <strong>The</strong>refore, the work <strong>of</strong> botanical gardens addressed<br />

not only the <strong>in</strong>troduction and cultivation <strong>of</strong> exotic <strong>plants</strong> but also<br />

research on native tropical forests (van Steenis & van Steenis-<br />

Krusemann, 1953) and the creation <strong>of</strong> public <strong>green</strong> areas <strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong><br />

cities like <strong>Bandung</strong>. <strong>The</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong> at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 20th century co<strong>in</strong>cided with the worldwide movement<br />

<strong>of</strong> Howard’s garden city concept, which addressed the needs for<br />

social improvement and quality <strong>of</strong> open space (Howard, 1902). In<br />

the 1930s, <strong>Bandung</strong>’s beautification movement began ambitious<br />

work and emphasized ecological approaches. Some years earlier,<br />

Christchurch went through a similar process as a young <strong>colonial</strong> city<br />

<strong>in</strong> New Zealand; from its beautification association <strong>in</strong> the 1890s,<br />

the city had valuable protagonists for city <strong>green</strong><strong>in</strong>g and the protection<br />

<strong>of</strong> native elements with<strong>in</strong> the municipality (Faggi & Ignatieva,<br />

2009).<br />

<strong>The</strong> assumption that elements <strong>of</strong> the historically recommended<br />

species pool still exist <strong>in</strong> recent <strong>parks</strong> and contribute to <strong>Bandung</strong>’s<br />

<strong>green</strong> <strong>heritage</strong> was verified by detect<strong>in</strong>g 75% <strong>of</strong> the historically recommended<br />

species with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>vestigated <strong>parks</strong>. <strong>The</strong>se species<br />

assemblages generate a local identity which is also supported by<br />

the species status, where 46% <strong>of</strong> the extant historical tree species<br />

were native to Java (53% were non-native). This amount <strong>of</strong> native<br />

woody park species could be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as a higher local identity<br />

than those <strong>in</strong> other former <strong>colonial</strong> cities, such as Christchurch (16%<br />

native species), Bangalore (34%) or Hong Kong (27%), when referr<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to the <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> tree species <strong>in</strong> urban <strong>parks</strong> (Jim, 2000;<br />

Nagendra & Gopal, 2010; Stewart, Ignatieva, Meurk, & Earl, 2004).<br />

However, also various non-native ornamental species, played<br />

important roles for urban park design and were historically recommended.<br />

<strong>Bandung</strong> had the non-gratuitous reputation as the City <strong>of</strong><br />

Flowers (Kunto, 1986).<br />

Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, the conceptual approaches for park design <strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong><br />

<strong>Bandung</strong> tended to use native species from close surround<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

<strong>in</strong> addition to extraord<strong>in</strong>ary exotic species, which can also be beneficial<br />

for creat<strong>in</strong>g a local identity (Tho et al., 1983). <strong>The</strong> considerable<br />

number <strong>of</strong> local species and the various other native species recommended<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>colonial</strong> era show that these elements can<br />

also be utilized for city <strong>green</strong><strong>in</strong>g, at least for the design <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>’s<br />

larger <strong>parks</strong>, which conta<strong>in</strong> a significantly higher proportion<br />

<strong>of</strong> native species than smaller <strong>parks</strong>. Especially <strong>in</strong> tropical <strong>colonial</strong><br />

cities, this approach was not as a matter <strong>of</strong> course. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

British <strong>colonial</strong> era <strong>in</strong> Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), for <strong>in</strong>stance, little<br />

was known about the properties and needs <strong>of</strong> native species,<br />

and well-known non-native species (e.g., Swietenia spp., Spathodea<br />

campanulata) were <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> the 1920s and 1930s (Sreetheran<br />

et al., 2006).<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g the historical concepts, there were several functions<br />

that were fulfilled by the recommended species, such as good site<br />

adaptation, shad<strong>in</strong>g, and primarily unique ornamental value. Similar<br />

to the approaches <strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong> Brazil, design features like color or<br />

texture were valued, and the use <strong>of</strong> exotic <strong>plants</strong> is still widespread<br />

(Santos dos, Bergallo, & Rocha, 2008). <strong>The</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> native and local<br />

ornamental species <strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong> resulted <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong><br />

several non-native tree and shrub species, ma<strong>in</strong>ly ornamentals<br />

from other New- and Old-World tropics. Similar f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs can be<br />

documented for Beij<strong>in</strong>g’s <strong>parks</strong>, where 63% <strong>of</strong> shrubs are nonnative<br />

ornamentals (Weifeng et al., 2006). However, the <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

<strong>of</strong> species with diet and medic<strong>in</strong>al purposes <strong>in</strong> public open spaces<br />

show that practical issues, <strong>in</strong> addition to ornamental values, tend<br />

to be important today. It could be assumed that the Municipality<br />

encourages the use <strong>of</strong> those species for public use <strong>in</strong> <strong>parks</strong> (e.g., fruit<br />

or flower pick<strong>in</strong>g dur<strong>in</strong>g immense public tree plant<strong>in</strong>g campaigns<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the last 5 years).<br />

<strong>The</strong> results <strong>of</strong> this study conform to those <strong>of</strong> studies <strong>of</strong> <strong>parks</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> Beij<strong>in</strong>g and Bangalore (Nagendra & Gopal, 2010; Weifeng et al.,<br />

2006) when show<strong>in</strong>g that park age is an important factor <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

species composition; however, each study def<strong>in</strong>ed different<br />

age categories. In this study, species recommended <strong>in</strong> historical<br />

concepts occur more <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>in</strong> <strong>parks</strong> that were created <strong>in</strong> <strong>colonial</strong><br />

times than <strong>in</strong> younger, post-<strong>colonial</strong> <strong>parks</strong>. Additionally, it can be<br />

shown that historical plant use significantly <strong>in</strong>corporated more<br />

local species. <strong>The</strong> tree <strong>in</strong>ventory <strong>in</strong> old <strong>parks</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicates an advanced<br />

utilization <strong>of</strong> local tree species, such as Ficus benjam<strong>in</strong>a, Elaeocarpus<br />

sphaericus or Syzygium polyanthum, and native tree species, such as<br />

Pterocarpus <strong>in</strong>dicus or Mimusops elengii. An important f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> this<br />

study is that the proportion <strong>of</strong> historical native and non-native trees<br />

was more balanced than <strong>in</strong> the recent tree composition. As <strong>in</strong> the<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigations <strong>in</strong> Bangalore, the ratio <strong>of</strong> non-native species is higher<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Bandung</strong>’s older <strong>parks</strong>, due to the higher amount <strong>of</strong> ornamental<br />

shrub and palm species.<br />

As <strong>in</strong>dicated <strong>in</strong> the cluster analysis, a group<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>parks</strong> can also<br />

give evidence about specific species compositions or design styles.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first park cluster is comprised <strong>of</strong> either old <strong>parks</strong> or <strong>parks</strong> that<br />

have not been redesigned s<strong>in</strong>ce the 1920s or 1930s. In the second<br />

cluster, most <strong>parks</strong> are either young or have been recently<br />

redesigned. <strong>The</strong> study’s oldest park, which orig<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong> 1885, is<br />

part <strong>of</strong> this rather homogeneous park cluster. <strong>The</strong> study’s focus on<br />

historical species <strong>in</strong>dicates a long development cont<strong>in</strong>uity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>parks</strong>.<br />

A transition <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> species choice with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>colonial</strong> period<br />

and more recent years is evident and was probably <strong>in</strong>fluenced by<br />

the respective bodies <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the design process. <strong>The</strong> oldest<br />

park, Merdeka, which was created by an enthusiastic botanist from<br />

the Bogor Botanical Garden, had the highest amount <strong>of</strong> native and<br />

local species. <strong>The</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g generation <strong>of</strong> park managers and city<br />

planners from the 1920s to 1930s ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed the idea <strong>of</strong> orientat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

on surround<strong>in</strong>g natural vegetation but also employed more<br />

aesthetical and formal aspects when design<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>parks</strong>, us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

additional ornamental species. As the study’s correlations verify,<br />

this generation <strong>of</strong> park managers and city planners differentiated<br />

the <strong>parks</strong> and the respective species <strong>in</strong>ventory <strong>in</strong> regard to park size<br />

and related function <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> pure collections <strong>of</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle species<br />

(Hendriks, 1940).<br />

In recent plant<strong>in</strong>gs (DBH < 0.1 m), Swietenia is most abundant,<br />

but also some native (Mimusops) and even local species (Syzygium,<br />

Elaeocarpus) are used. When referr<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>formal statements <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Municipality, the most frequent tree, Mahogany (Swietenia sp.), is<br />

the easiest species to propagate and grow under urban conditions<br />