Clovis Comet Debate - The Archaeological Conservancy

Clovis Comet Debate - The Archaeological Conservancy

Clovis Comet Debate - The Archaeological Conservancy

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

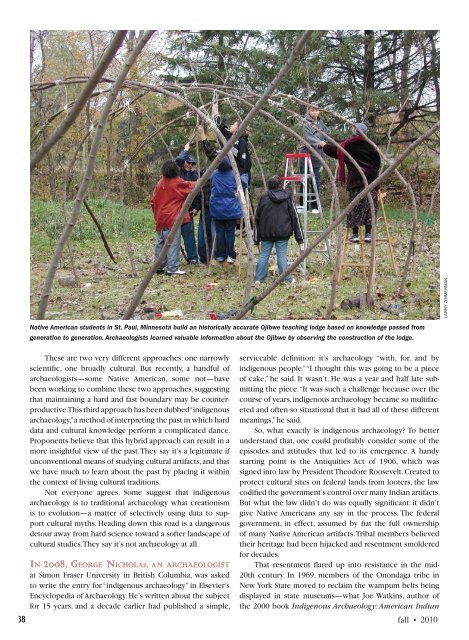

Native American students in St. Paul, Minnesota build an historically accurate Ojibwe teaching lodge based on knowledge passed from<br />

generation to generation. Archaeologists learned valuable information about the Ojibwe by observing the construction of the lodge.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se are two very different approaches: one narrowly<br />

scientific, one broadly cultural. But recently, a handful of<br />

archaeologists—some Native American, some not—have<br />

been working to combine these two approaches, suggesting<br />

that maintaining a hard and fast boundary may be counterproductive.<br />

This third approach has been dubbed “indigenous<br />

archaeology,” a method of interpreting the past in which hard<br />

data and cultural knowledge perform a complicated dance.<br />

Proponents believe that this hybrid approach can result in a<br />

more insightful view of the past. <strong>The</strong>y say it’s a legitimate if<br />

unconventional means of studying cultural artifacts, and that<br />

we have much to learn about the past by placing it within<br />

the context of living cultural traditions.<br />

Not everyone agrees. Some suggest that indigenous<br />

archaeology is to traditional archaeology what creationism<br />

is to evolution—a matter of selectively using data to support<br />

cultural myths. Heading down this road is a dangerous<br />

detour away from hard science toward a softer landscape of<br />

cultural studies. <strong>The</strong>y say it’s not archaeology at all.<br />

In 2008, ge o rg e nI c h o l a s, an a rc h a e o l o g I s t<br />

at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, was asked<br />

to write the entry for “indigenous archaeology” in Elsevier’s<br />

Encyclopedia of Archaeology. He’s written about the subject<br />

for 15 years, and a decade earlier had published a simple,<br />

serviceable definition: it’s archaeology “with, for, and by<br />

indigenous people.” “I thought this was going to be a piece<br />

of cake,” he said. It wasn’t. He was a year and half late submitting<br />

the piece. “It was such a challenge because over the<br />

course of years, indigenous archaeology became so multifaceted<br />

and often so situational that it had all of these different<br />

meanings,” he said.<br />

So, what exactly is indigenous archaeology? To better<br />

understand that, one could profitably consider some of the<br />

episodes and attitudes that led to its emergence. A handy<br />

starting point is the Antiquities Act of 1906, which was<br />

signed into law by President <strong>The</strong>odore Roosevelt. Created to<br />

protect cultural sites on federal lands from looters, the law<br />

codified the government’s control over many Indian artifacts.<br />

But what the law didn’t do was equally significant: it didn’t<br />

give Native Americans any say in the process. <strong>The</strong> federal<br />

government, in effect, assumed by fiat the full ownership<br />

of many Native American artifacts. Tribal members believed<br />

their heritage had been hijacked and resentment smoldered<br />

for decades.<br />

That resentment flared up into resistance in the mid-<br />

20th century. In 1969, members of the Onondaga tribe in<br />

New York State moved to reclaim the wampum belts being<br />

displayed in state museums—what Joe Watkins, author of<br />

the 2000 book Indigenous Archaeology: American Indian<br />

38 fall • 2010<br />

larry zimmerman