Clovis Comet Debate - The Archaeological Conservancy

Clovis Comet Debate - The Archaeological Conservancy

Clovis Comet Debate - The Archaeological Conservancy

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

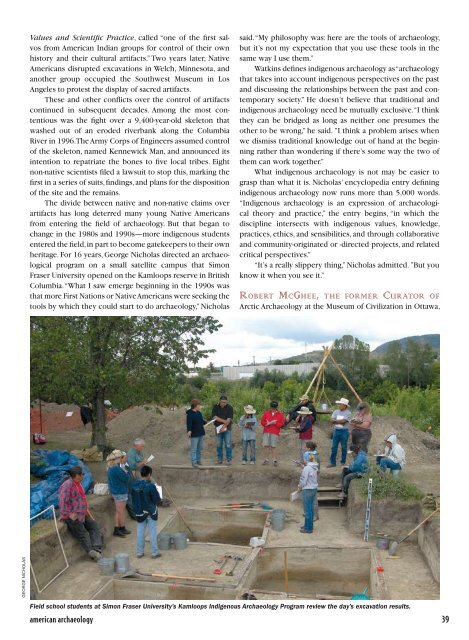

george nicHolaS<br />

Values and Scientific Practice, called “one of the first salvos<br />

from American Indian groups for control of their own<br />

history and their cultural artifacts.” Two years later, Native<br />

Americans disrupted excavations in Welch, Minnesota, and<br />

another group occupied the Southwest Museum in Los<br />

Angeles to protest the display of sacred artifacts.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se and other conflicts over the control of artifacts<br />

continued in subsequent decades. Among the most contentious<br />

was the fight over a 9,400-year-old skeleton that<br />

washed out of an eroded riverbank along the Columbia<br />

River in 1996. <strong>The</strong> Army Corps of Engineers assumed control<br />

of the skeleton, named Kennewick Man, and announced its<br />

intention to repatriate the bones to five local tribes. Eight<br />

non-native scientists filed a lawsuit to stop this, marking the<br />

first in a series of suits, findings, and plans for the disposition<br />

of the site and the remains.<br />

<strong>The</strong> divide between native and non-native claims over<br />

artifacts has long deterred many young Native Americans<br />

from entering the field of archaeology. But that began to<br />

change in the 1980s and 1990s—more indigenous students<br />

entered the field, in part to become gatekeepers to their own<br />

heritage. For 16 years, George Nicholas directed an archaeological<br />

program on a small satellite campus that Simon<br />

Fraser University opened on the Kamloops reserve in British<br />

Columbia. “What I saw emerge beginning in the 1990s was<br />

that more First Nations or Native Americans were seeking the<br />

tools by which they could start to do archaeology,” Nicholas<br />

said. “My philosophy was: here are the tools of archaeology,<br />

but it’s not my expectation that you use these tools in the<br />

same way I use them.”<br />

Watkins defines indigenous archaeology as “archaeology<br />

that takes into account indigenous perspectives on the past<br />

and discussing the relationships between the past and contemporary<br />

society.” He doesn’t believe that traditional and<br />

indigenous archaeology need be mutually exclusive. “I think<br />

they can be bridged as long as neither one presumes the<br />

other to be wrong,” he said. ”I think a problem arises when<br />

we dismiss traditional knowledge out of hand at the beginning<br />

rather than wondering if there’s some way the two of<br />

them can work together.”<br />

What indigenous archaeology is not may be easier to<br />

grasp than what it is. Nicholas’ encyclopedia entry defining<br />

indigenous archaeology now runs more than 5,000 words.<br />

“Indigenous archaeology is an expression of archaeological<br />

theory and practice,” the entry begins, “in which the<br />

discipline intersects with indigenous values, knowledge,<br />

practices, ethics, and sensibilities, and through collaborative<br />

and community-originated or -directed projects, and related<br />

critical perspectives.”<br />

“It’s a really slippery thing,” Nicholas admitted. ”But you<br />

know it when you see it.”<br />

rob e rt mcghe e, t h e f o r m e r cu r at o r o f<br />

Arctic Archaeology at the Museum of Civilization in Ottawa,<br />

Field school students at Simon Fraser University’s Kamloops Indigenous Archaeology Program review the day’s excavation results.<br />

american archaeology 39