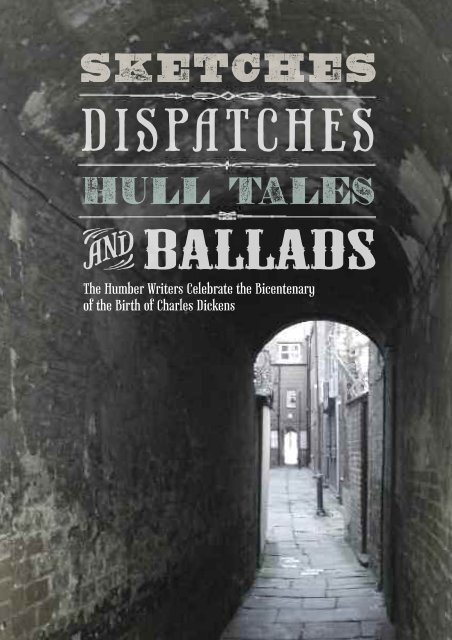

Sketches, Dispatches, Hull Tales and Ballads - University of Hull

Sketches, Dispatches, Hull Tales and Ballads - University of Hull

Sketches, Dispatches, Hull Tales and Ballads - University of Hull

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

A Humber Mouth Special Commission 2012. Copyright <strong>of</strong> individual poems, stories<br />

<strong>and</strong> images resides with the writers <strong>and</strong> artists. Humber Mouth 2012 acknowledges the<br />

financial assistance <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> City Council <strong>and</strong> Arts Council Engl<strong>and</strong>, Yorkshire.<br />

British Library Cataloguing in Publications Data.<br />

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library.<br />

First published 2012<br />

Published by Kingston Press<br />

All rights reserved. No part <strong>of</strong> this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval<br />

system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical,<br />

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission <strong>of</strong> the publishers.<br />

is book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way <strong>of</strong> trade or otherwise,<br />

be lent, resold, hired or otherwise circulated, in any form <strong>of</strong> binding or cover other<br />

than that in which it is published, without the publisher’s prior consent.<br />

e Authors assert the moral right to be identified as the Authors <strong>of</strong> the work in<br />

accordance with the Copyright Design <strong>and</strong> Patents Act 1988.<br />

ISBN 978-1-902039-22-0<br />

Kingston Press is the publishing imprint <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> City Council Library Service,<br />

Central Library, Albion Street, <strong>Hull</strong>, Engl<strong>and</strong>, HU1 3TF<br />

Telephone: +44 (0) 1482 210000<br />

Fax: +44 (0) 1482 616827<br />

e-mail: kingstonpress@hullcc.gov.uk<br />

www.hullcc.co.uk/kingstonpress

We are pleased to present <strong>Sketches</strong>, <strong>Dispatches</strong>, <strong>Hull</strong> <strong>Tales</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Ballads</strong>, the<br />

latest collaboration from the Humber Writers. Here you have an anthology<br />

<strong>of</strong> words <strong>and</strong> images responding, sometimes directly, sometimes more<br />

obliquely, to Dickens, as we celebrate the bicentenary <strong>of</strong> his birth. The book<br />

is a Humber Mouth Special Commission which echoes <strong>and</strong> plays variations<br />

on the themes <strong>of</strong> Hard Times, Great Expectations — the watchwords <strong>of</strong> this<br />

year’s festival.<br />

The Humber Writers is a group <strong>of</strong> poets, fiction writers <strong>and</strong> artists<br />

associated with the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>. Over the years members <strong>of</strong> the group<br />

have collaborated on a number <strong>of</strong> projects specifically focusing on <strong>Hull</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

its neighbouring l<strong>and</strong>scapes, <strong>of</strong>ten resulting in books, performances <strong>and</strong><br />

film for the Humber Mouth Literature Festival: A Case for the Word (theatre<br />

performance, 2006); Architexts (art book, 2007); Dri (book <strong>and</strong> film, 2008);<br />

Hide (book, 2010); <strong>and</strong> Postcards from <strong>Hull</strong> (book, postcards <strong>and</strong> art<br />

exhibition, 2011). 2012 has been particularly productive as this book<br />

follows hard on the heels <strong>of</strong> Under Travelling Skies: Departures from Larkin,<br />

which won the first Larkin25 Words Award, <strong>and</strong> featured a book, a film <strong>and</strong><br />

an exhibition <strong>of</strong> paintings at Artlink in Princes Avenue, <strong>Hull</strong>.<br />

Dickens, <strong>of</strong> course, is most immediately associated with London <strong>and</strong> so<br />

our ‘departures from Dickens’ <strong>of</strong>ten reflect our own city through his themes.<br />

Dickens did visit <strong>Hull</strong>: several <strong>of</strong> the pieces here refer to an incident which<br />

involved him buying silk stockings, presumably for the actress Ellen Ternan,<br />

<strong>and</strong> giving the shop assistant who served him a ticket for one <strong>of</strong> his readings.<br />

There is some doubt as to when (or even if?) this took place. As editors we<br />

have sought an imaginative response, <strong>and</strong> have allowed our writers<br />

sufficient leeway with Gradgrind’s facts to make what they will <strong>of</strong> anecdote,<br />

false report, misremembered date, or for that matter history itself.<br />

It has been a great pleasure editing this anthology <strong>and</strong> we would like to<br />

thank <strong>Hull</strong> City Arts who generously supported the project.<br />

Mary Aherne <strong>and</strong> Cliff Forshaw, <strong>Hull</strong>, June 2012.

2<br />

Painting: Nude with Top Hat 1 by Cliff Forshaw

Contents<br />

Maurice Rutherford.............. Apology for Absence............................. 4<br />

Valerie S<strong>and</strong>ers...................... Dickens <strong>and</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>: An Introduction.... 5<br />

Mary Aherne........................... Imp........................................................... 12<br />

Malcolm Watson.................... Silk Stockings......................................... 14<br />

Carol Rumens.......................... e Gentleman for Nowhere................ 16<br />

Aingeal Clare.......................... e Man <strong>and</strong> the Peregrine <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Chimney.................................................<br />

Cliff Forshaw.......................... A Trinity <strong>of</strong> Genomic Portraits for<br />

30<br />

Charles Darwin...................................... 32<br />

David Wheatley...................... Cat Head eatre................................... 38<br />

Wanna Come Back to Mine................. 40<br />

Cliff Forshaw.......................... A Season in <strong>Hull</strong>.................................... 42<br />

Ingerl<strong>and</strong>................................................. 43<br />

Ray French............................... Insomnia................................................. 48<br />

Cliff Forshaw.......................... Two <strong>Ballads</strong> from the Bush................... 62<br />

David Wheatley...................... Northern Divers..................................... 71<br />

Guns on the Bus..................................... 72<br />

Carol Rumens.......................... Beware this Boy...................................... 74<br />

Aingeal Clare.......................... from Wide Country <strong>and</strong> the Road......<br />

Kath McKay............................ <strong>Hull</strong> <strong>and</strong> Eastern Counties Herald<br />

75<br />

March 1869............................................. 83<br />

Aer the Silk Stockings......................... 84<br />

Aer Abigail Finds the Letter............... 89<br />

Malcolm Watson.................... A Christmas Carol................................. 94<br />

David Wheatley...................... Interview with a Binman...................... 95<br />

Visitors’ Centre....................................... 96<br />

Vacuous <strong>and</strong> Unknown......................... 97<br />

Jane Thomas........................... Charles Dickens <strong>and</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>..................... 98<br />

Mary Aherne........................... Hope on the Horizon............................ 104<br />

birds.........................................................110<br />

Maurice Rutherford.............. Second oughts....................................112<br />

3

4<br />

Maurice Rutherford<br />

Apology for Absence<br />

Dear Editor,<br />

Moved by, <strong>and</strong> grateful for<br />

your invitation to present a script –<br />

something <strong>of</strong> expectations, great or small,<br />

hard times, health, poverty, philanthropy,<br />

<strong>of</strong> which <strong>Hull</strong>’s known its share, both good <strong>and</strong> bad –<br />

I have to say my contribution would<br />

entail recourse to reference books today<br />

<strong>and</strong> here’s the rub: I’ve given them away.<br />

Cerebral palsy, surely blighting births<br />

when Magwitch stirred the marshl<strong>and</strong> mists, still does,<br />

so, heeding a request to donate books<br />

(whose small print now lay fogged beyond my reach)<br />

chancing a bicentenary salute<br />

to one who wrote life as it was, backlit<br />

with love, <strong>and</strong> left a legacy <strong>of</strong> hope,<br />

I bagged my Dickens paperbacks for Scope.<br />

Two feet <strong>of</strong> empty shelf, some disturbed dust,<br />

Pickwick <strong>and</strong> Nickleby – both hardback gifts<br />

from absent friends taken before their time –<br />

remain, reminding me <strong>of</strong> kindnesses<br />

that came my way, like this approach from you<br />

I can’t feel equal to. Forgive me when<br />

with gratitude <strong>and</strong>, yes, resurgent grief<br />

I must, ungraciously, decline this brief.<br />

ps. May I append the shortest gloss:<br />

no giving’s worth its name where there’s no loss.

Valerie S<strong>and</strong>ers<br />

Dickens <strong>and</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>: An Introduction<br />

The <strong>Hull</strong> people (not generally considered excitable, even on<br />

their own showing), were so enthusiastic that we were<br />

obliged to promise to go back there for Two Readings!<br />

(letter, 15 September 1858)<br />

What did Dickens know – or care – about <strong>Hull</strong>? As a ‘southerner’,<br />

born in Portsmouth, but popularly regarded by most people as a<br />

Londoner, he might look like the last person to have anything<br />

interesting to say about a provincial town on the Humber estuary.<br />

As the opening quotation shows, however, he came to <strong>Hull</strong> in<br />

September 1858 on one <strong>of</strong> his famous public reading tours, <strong>and</strong> was<br />

an instant success. His letters record that he made ‘more than £50<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>it at <strong>Hull</strong>’ on his first reading, <strong>and</strong> returned by popular dem<strong>and</strong><br />

a few weeks later. However strapped for cash people were clearly<br />

willing to turn out twice to hear the nation’s best-loved novelist<br />

perform favourite extracts from his works, as they did on his return<br />

visits in 1859 <strong>and</strong> 60. He was back again in 1869 for his farewell<br />

reading tour, when he stayed at the Royal Station Hotel, <strong>and</strong> regaled<br />

an audience at the Assembly Rooms (later the New Theatre) with<br />

another round <strong>of</strong> his old favourites, including ‘Sikes <strong>and</strong> Nancy’ <strong>and</strong><br />

‘Mrs Gamp.’ We know the people <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> loved Dickens on tour, but<br />

apart from these performance pieces, what else in his novels suggests<br />

they might have struck a chord with the audience he entertained?<br />

And given today’s ‘hard times’ what can we still find in Dickens to<br />

speak to our own experience <strong>of</strong> austerity <strong>and</strong> hardship?<br />

The most obvious link between Dickens <strong>and</strong> his <strong>Hull</strong> audience,<br />

both past <strong>and</strong> present, is their shared familiarity with rivers,<br />

estuaries, bridges, the flat, featureless l<strong>and</strong>scape, <strong>and</strong> the varieties <strong>of</strong><br />

shipping which ploughed up <strong>and</strong> down their muddy waters. A<br />

Victorian commentator on <strong>Hull</strong>, the Revd James Sibree, dated his<br />

letters home to his mother as ‘From the fag-end <strong>of</strong> the earth.’<br />

5

6<br />

Reaching Barton after an exhausting twenty-six hour journey from<br />

London in 1831, he remembered how the ‘flatness <strong>of</strong> the country<br />

palled on my spirit’ – <strong>and</strong> there was still the river crossing to make<br />

by small steamboat, loaded with cattle as well as his fellowpassengers<br />

<strong>and</strong> their luggage. 1 Much <strong>of</strong> this apparently dreary<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape might have reminded Dickens <strong>of</strong> the Kent marshes, which<br />

he had known from childhood when his father worked in the Navy<br />

Pay Offices based at Sheerness <strong>and</strong> Chatham, towns which feature<br />

in several <strong>of</strong> his novels including e Pickwick Papers <strong>and</strong> David<br />

Copperfield. At his least charitable, he nicknamed the Kent towns <strong>of</strong><br />

his childhood, especially Rochester, ‘Dullborough’ <strong>and</strong> ‘Mudfog’,<br />

while in Great Expectations (1860-1) his hero Pip overhears a convict<br />

recall the marshes as ‘“A most beastly place. Mudbank, mist, swamp,<br />

<strong>and</strong> work; work, swamp, mist, <strong>and</strong> mudbank”’ (Ch. 28). The banks<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Humber in a dripping November mist might be similarly<br />

described.<br />

The Humber might have reminded Dickens <strong>of</strong> another, gr<strong>and</strong>er<br />

river estuary which became an integral part <strong>of</strong> his life when he<br />

worked at Warren’s blacking warehouse on Hungerford Steps. The<br />

Thames is a murky <strong>and</strong> fairly sinister presence in many <strong>of</strong> his novels,<br />

from Oliver Twist (1838) to Our Mutual Friend (1864-5), which<br />

opens with the image <strong>of</strong> ‘a boat <strong>of</strong> dirty <strong>and</strong> disreputable appearance,<br />

with two figures in it,’ floating between Southwark <strong>and</strong> London<br />

Bridge on an autumn evening. Given the perpetual brown sludgy<br />

appearance <strong>of</strong> today’s Humber it is easy to recognize Dickens’s<br />

references to the ‘slime <strong>and</strong> ooze’ <strong>of</strong> rivers, though what chiefly<br />

interests him in these watery l<strong>and</strong>scapes is the human traffic. Gaffer<br />

Hexam <strong>and</strong> his daughter Lizzie are here shown trawling not for fish,<br />

but for dead bodies, <strong>and</strong> when the river features in Great<br />

Expectations, it is in relation to human cargoes <strong>of</strong> convicts. Opening<br />

in the Kent marshes, the novel plunges the reader straight into<br />

knowledge <strong>of</strong> the ‘Hulks’ or holding vessels for prisoners ready to<br />

be shipped <strong>of</strong>f to Australia. ‘By the light <strong>of</strong> the torches,’ Dickens’s<br />

young autobiographical narrator Pip recalls, when he sees the

terrifying convict Magwitch h<strong>and</strong>ed over to the authorities, ‘we saw<br />

the black Hulk lying out a little way from the mud <strong>of</strong> the shore, like<br />

a wicked Noah’s ark’ (Ch.5). When Magwitch risks his life returning<br />

to Engl<strong>and</strong> over a decade later to visit the boy whose education he<br />

has been secretly subsidising, Pip <strong>and</strong> his friend Herbert Pocket<br />

concoct an elaborate plan to help him escape before he can be caught<br />

a second time. Their intention is to row him down the Thames to<br />

where he can catch a steamer either for Hamburg or for Rotterdam:<br />

destinations he could also have reached from <strong>Hull</strong>, whose grim<br />

prison (1865-70) on Hedon Road was built in the same decade as<br />

the publication <strong>of</strong> Great Expectations. Typically for Dickens, who<br />

rarely allows wrong-doers, however well-meaning, to escape scotfree,<br />

Magwitch is rearrested before he can board either <strong>of</strong> the<br />

European steamers, <strong>and</strong> dies peacefully in jail, instead <strong>of</strong> being<br />

hanged as a returned transport.<br />

Even when Dickens opens a novel by describing the London<br />

streets, as in the famous foggy opening chapter <strong>of</strong> Bleak House<br />

(1853), they seem to blend with the Thames, in one continuous haze<br />

<strong>of</strong> grey shapes <strong>and</strong> adjacent counties – the Essex Marshes <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Kentish heights, ‘fog lying out on the yards, <strong>and</strong> hovering in the<br />

rigging <strong>of</strong> great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales <strong>of</strong> barges <strong>and</strong><br />

small boats.’ Why does Dickens so <strong>of</strong>ten evoke these misty maritime<br />

scenes at the beginnings <strong>of</strong> his novels? Does he want to convey the<br />

common mystery <strong>of</strong> cities <strong>and</strong> rivers as places <strong>of</strong> human traffic so<br />

complex <strong>and</strong> multifaceted, seething below <strong>and</strong> beyond human vision<br />

that only gradually can he begin to pick out faces <strong>and</strong> personal<br />

histories from the general blur? In this passage from Bleak House,<br />

he also notices ‘Chance people on the bridges peeping over the<br />

parapets into a nether sky <strong>of</strong> fog, with fog all round them, as if they<br />

were up in a balloon, <strong>and</strong> hanging in the misty clouds.’<br />

This reminds us that bridges, too, fascinated Dickens, both as<br />

l<strong>and</strong>marks in themselves, <strong>and</strong> places where people pause, take stock<br />

<strong>of</strong> things, <strong>and</strong> arrange secret assignations, as Nancy does at London<br />

Bridge with Mr Brownlow <strong>and</strong> Rose Maylie, Oliver’s protectors, in<br />

7

8<br />

Oliver Twist. Despite its gr<strong>and</strong>eur, the Thames at nearly midnight,<br />

looks as muddy <strong>and</strong> marshy as the Kent l<strong>and</strong>scape, with its riverside<br />

buildings , the old ‘smoke-stained storehouses on either side,’ rising<br />

‘heavy <strong>and</strong> dull from the dense mass <strong>of</strong> ro<strong>of</strong>s <strong>and</strong> gables,’ the ‘forest<br />

<strong>of</strong> shipping below bridge’ almost invisible in the darkness (Ch. 46).<br />

London Bridge makes another fleeting appearance in Great<br />

Expectations, as Magwitch is rowed down river, past the kind <strong>of</strong><br />

waterfront scenery which clearly fascinated Dickens in novel after<br />

novel. However urgent the pressures <strong>of</strong> plot, he always takes time to<br />

note the maritime clutter <strong>of</strong> dockyards, which Pip recalls as ‘rusty<br />

chain-cables, frayed hempen hawsers <strong>and</strong> bobbing buoys,’ down to<br />

the level <strong>of</strong> miscellaneous surface rubbish as their boat momentarily<br />

collides with ‘floating broken baskets, scattering floating chips <strong>of</strong><br />

wood <strong>and</strong> shaving, cleaving floating scum <strong>of</strong> coal’ (Ch.54). There<br />

was clearly little about rivers, or dockyards, which Dickens failed to<br />

observe throughout his life. David Copperfield, on his way to stay<br />

for the first time in Mr Peggotty’s wonderful upturned boat-house<br />

in Yarmouth, notices every scrap <strong>of</strong> nautical debris which builds his<br />

excitement as they near the beach: the ‘lanes bestrewn with bits <strong>of</strong><br />

chips <strong>and</strong> little hillocks <strong>of</strong> s<strong>and</strong>,’ ‘the gas-works, rope-walks, boatbuilders’<br />

yards, shipwrights’ yards, ship-breakers’ yards, caulkers’<br />

yards, riggers’ l<strong>of</strong>ts, smiths’ forges, <strong>and</strong> a great litter <strong>of</strong> such places’<br />

(Ch. 3). In rhythmic, lilting lists like this Dickens is half way towards<br />

a poem, sharing his hero’s excitement about everything to do with<br />

the sea <strong>and</strong> rivers. The strange sound <strong>of</strong> the technical terms –<br />

‘caulkers’, <strong>and</strong> ‘rope-walks’ – fascinates him, removed as it is from<br />

the language <strong>of</strong> everyday life, <strong>and</strong> redolent <strong>of</strong> places where men do<br />

real work in tough physical conditions. His late series <strong>of</strong> essays, e<br />

Uncommercial Traveller (1860-9), takes this further in a chapter on<br />

the bustling life <strong>of</strong> ‘Down by the Docks’: in this case, the Rochester<br />

waterfront, where he lists in dizzying detail the food, drink, oysters,<br />

fishy, scaly-looking vegetables, public-houses, c<strong>of</strong>fee-shops, drunken<br />

seamen with tattooed arms, sausages <strong>and</strong> saveloys, hornpipes,<br />

parrots, waxworks, <strong>and</strong> poetic placards rhyming: ‘Come, cheer up

my lads. We’ve the best liquors here, And you’ll find something new<br />

In our wonderful Beer’ (Ch. 22) – poetry <strong>of</strong> a lesser kind, but still<br />

inspired by a sense <strong>of</strong> place. Dickens, in a word, for all his<br />

associations with London, was steeped in the liminal, perpetually<br />

unsettled, restless world <strong>of</strong> river <strong>and</strong> sea traffic, with all its shoreline<br />

dramas, failed escapes <strong>and</strong> fatal encounters.<br />

The creative writers who have contributed to this volume have<br />

drawn much <strong>of</strong> their inspiration from two <strong>of</strong> the shorter Dickens<br />

texts: Hard Times (1854) <strong>and</strong> Great Expectations. Significantly<br />

different though they are, they share certain themes which still speak<br />

to today’s readers, not least through their interwoven motifs <strong>of</strong> money<br />

<strong>and</strong> poverty, work, aspiration, ambition, <strong>and</strong> education, which<br />

troubled Dickens throughout his career. A pervasive concern <strong>of</strong><br />

Dickens’s writing remains the unbridgeable chasm between rich <strong>and</strong><br />

poor, <strong>and</strong> the ways in which impoverished families scrape together a<br />

basic subsistence. Broken homes <strong>and</strong> families feature in all his novels,<br />

as do the reconstituted ‘families <strong>of</strong> choice,’ where people with no<br />

biological connection share lodgings <strong>and</strong> food, as in David<br />

Copperfield, where Mr Peggotty’s eccentric, but all-inclusive<br />

household numbers – besides his orphaned niece <strong>and</strong> nephew (Little<br />

Emily <strong>and</strong> Ham) – the sorrowful Mrs Gummidge, widow <strong>of</strong> his<br />

partner in a boat. The Peggottys’ ‘ship-looking thing’ (as David calls<br />

their home) is a healthier place to live than the overcrowded city<br />

tenements, like those <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> when cholera epidemics struck the town<br />

in 1832 <strong>and</strong> 1849. James Sibree recalls how the streets ‘were ill-paved,<br />

<strong>and</strong> unfrequently swept’ (p. 10). Unlike the uniform streets <strong>of</strong><br />

Dickens’s Coketown in Hard Times (based on the Lancashire mill<br />

town <strong>of</strong> Preston), the houses <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> ‘were irregularly built- scarcely<br />

any two alike’ (Sibree, p. 10). Sibree was disappointed by the lack <strong>of</strong><br />

gr<strong>and</strong>eur in the public buildings, only Holy Trinity Church, the<br />

Infirmary <strong>and</strong> Public Rooms st<strong>and</strong>ing out from the monotonous<br />

townscape, making them little better than those <strong>of</strong> Coketown, where<br />

‘the jail might have been the infirmary, the infirmary might have been<br />

the jail, the town-hall might have been either, or both, or anything<br />

9

10<br />

else (Book the First: Chapter 5). The <strong>Hull</strong> workhouse – that archetypal<br />

Dickensian symbol <strong>of</strong> social protest – had existed since 1698. Though<br />

Victorian <strong>Hull</strong> had its fair share <strong>of</strong> distinguished visitors, including<br />

Queen Victoria, who in 1854 stayed (like Dickens) at the Station<br />

Hotel, <strong>and</strong> was moved by the sight <strong>of</strong> hundreds <strong>of</strong> loyal Sunday<br />

School children assembling to greet her, it was, by all accounts,<br />

essentially an earnest workaday kind <strong>of</strong> place, sustained economically<br />

by the whaling <strong>and</strong> fishing industries, <strong>and</strong> spiritually by more than<br />

its fair share <strong>of</strong> churches <strong>and</strong> chapels – not unlike Coketown’s chapels<br />

built by members <strong>of</strong> eighteen different religious sects.<br />

Though cotton mills briefly existed in <strong>Hull</strong> 2 the Coketown <strong>of</strong> Hard<br />

Times conveys the sense <strong>of</strong> a more mechanical <strong>and</strong> deadening<br />

industrial l<strong>and</strong>scape than Dickens would have found here. Even<br />

Coketown has its <strong>of</strong>f-duty moments, however, in the form <strong>of</strong> Sleary’s<br />

Horse-Riding, which shares features with the Victorian version <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Hull</strong> Fair: an assembly <strong>of</strong> market stalls, freak-shows, <strong>and</strong> circus acts<br />

as well as the new steam-driven roundabouts. Displays <strong>of</strong><br />

horsemanship, such as those performed by Mr Sleary <strong>and</strong> his troupe,<br />

are known to have been staged in the Market Place in <strong>Hull</strong>, where<br />

visitors might also be treated twice-daily to shows <strong>of</strong> ‘Dancing,<br />

Singing, Tumbling, Learned Ponies, Feats on the Wire.’ 3 Dickens was<br />

always a great advocate <strong>of</strong> popular entertainment, epitomised in Mr<br />

Sleary’s famous lisping insistence that ‘“People must be amuthed,<br />

Thquire, thomehow,”’ <strong>and</strong> ‘“can’t be alwath a working, nor yet they<br />

can’t be alwayth a learning”’ (Book the First: Ch. 6). Hence the<br />

Gradgrind children’s desperation to escape from the ‘mineralogical<br />

cabinets’ <strong>of</strong> their great square lecturing-castle <strong>of</strong> a house, <strong>and</strong> peep<br />

inside the circus tent for a glimpse <strong>of</strong> ‘but a ho<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> the graceful<br />

equestrian Tyrolean flower-act’ (Book the First: Ch. 3). When the<br />

novel ends with another secret mission to ship a criminal abroad<br />

(this time the hapless Tom Gradgrind who has robbed a bank), the<br />

circus people conceal him first in comic livery, <strong>and</strong> then disguise him<br />

afresh as a carter, so that he can escape without attracting notice.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> Dickens’s shortest, most succinctly-written novels, Hard

Times starkly contrasts the monotonous routines <strong>of</strong> the factory with<br />

the bizarre unreality <strong>of</strong> the circus: a wild zone on the edge <strong>of</strong> the<br />

town where for a brief spell the imagination can be indulged <strong>and</strong><br />

the workplace forgotten. The greatest satisfactions, for many<br />

Dickensian characters, come from imaginative reading, such as the<br />

nursery rhymes <strong>and</strong> fairytales the little Gradgrinds are forbidden to<br />

read, or from the real-life experiences <strong>of</strong> going to fairs, circuses <strong>and</strong><br />

Punch <strong>and</strong> Judy shows, which feature in so many <strong>of</strong> Dickens’s novels<br />

– but these are only intervals in a life <strong>of</strong> work, poverty <strong>and</strong><br />

aspiration. Together, Hard Times <strong>and</strong> Great Expectations create<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>of</strong> frustration for their leading characters. Monotony <strong>and</strong><br />

limited opportunity in each place crush the life out <strong>of</strong> anyone who<br />

wants more from existence than the rhythms <strong>of</strong> routine, or an<br />

education that never recognizes the individual potential <strong>of</strong> every<br />

child. In crazy Miss Havisham, jilted at the altar <strong>and</strong> determined for<br />

evermore to have her revenge on men, or Stephen Blackpool, the<br />

dogged factory worker saddled with a drunken addict <strong>of</strong> a wife he<br />

can never divorce, or Louisa Gradgrind, married for convenience to<br />

the bumptious banker, Mr Bounderby, Dickens acknowledges the<br />

hopelessness <strong>of</strong> the mundane domestic tragedies which afflicted<br />

Victorians <strong>of</strong> all classes <strong>and</strong> in all parts <strong>of</strong> the country. Every life is<br />

important to Dickens, just as each piece <strong>of</strong> maritime flotsam catches<br />

his eye. The people on the bridge matter, as do those rowing down<br />

the river to another life, <strong>and</strong> those staying at home to spin cotton,<br />

or carve something wondrous out <strong>of</strong> whalebone brought home from<br />

the distant seas.<br />

1 James Sibree, Fiy Years’ Recollections <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>, or Half-a-Century <strong>of</strong> Public Life <strong>and</strong> Ministry<br />

(<strong>Hull</strong>: A Brown & Sons, 1884), p. 8.<br />

2 David <strong>and</strong> Susan Neave, <strong>Hull</strong> (Pevsner Architectural Guides) (New Haven <strong>and</strong> London: Yale<br />

<strong>University</strong> Press, 2010) , p. 15.<br />

3 See http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/v/victorian-circus/<br />

11

12<br />

Mary Aherne<br />

Imp<br />

‘I saw the angel in the marble <strong>and</strong> carved until I set him free.’<br />

Michelangelo<br />

The day is fading, dusky shadows<br />

creep between pillars, whisper in the crypt,<br />

caress the chancel’s chiaroscuro.<br />

Tucked away, hidden in half-light<br />

he bides his time, keeps watchful guard<br />

outside the door, hovers out <strong>of</strong> sight<br />

<strong>of</strong> pious priests <strong>and</strong> the shuffling horde<br />

<strong>of</strong> tourists. They sense a presence in the air<br />

a curse or promise left unsaid.<br />

Someone, something else is there.<br />

An other-worldly presence skulks,<br />

torments this sacred place <strong>of</strong> prayer.<br />

Crouched beneath the pillar’s bulk,<br />

gurning through cracked, mephitic teeth,<br />

a hacked-out, hunchback takes<br />

you by surprise. Terror tempered with a grin<br />

set free yet harnessed for eternity<br />

its evil mutterings locked in stone.

14<br />

Malcolm Watson<br />

Silk Stockings<br />

‘Mr CHARLES DICKENS, the eminent novelist, gives “readings” in <strong>Hull</strong>.’<br />

<strong>Hull</strong> <strong>and</strong> Eastern Counties Herald, March 10th, 1869<br />

And on the previous day, he signs the register<br />

at the Royal Hotel, pleased by his reception, pleased<br />

by the respectful glances <strong>of</strong> the porters <strong>and</strong> the waiters<br />

glancing <strong>of</strong>f the mirrors at his side, in front, behind.<br />

The mirrors he can never pass, in which he views himself<br />

as spectacle, his smiles, his scowls, his countenance, his eyes,<br />

his carriage, cast, demeanour, diorama, the second-by-second<br />

reflection <strong>of</strong> that vaudeville <strong>of</strong> himself he scrutinizes all his life.<br />

Mirrors that surround him, watching, when he dies.<br />

Later, he takes a glass, a small glass, an abstemious<br />

glass (as is his habit) <strong>of</strong> br<strong>and</strong>y <strong>and</strong> water before<br />

the survey, the very careful survey, <strong>of</strong> the venue for<br />

the reading at the Assembly Rooms tomorrow night.<br />

Stage <strong>and</strong> seating, flat-topped desk <strong>and</strong> crimson cloth,<br />

maroon carpet, maroon screens, gas lamps in shining<br />

tin reflectors lighting up his face amid the shadows.<br />

Acoustics, props, gold watch chain, geranium for<br />

his buttonhole. Nothing less than perfect. Exactly right.<br />

Next day, he searches out a fancy haberdasher, <strong>Hull</strong>’s<br />

leading silk merchant, <strong>and</strong> buys six pairs <strong>of</strong> stockings<br />

for his Nell. He asks the shop lad (who has failed to recognize<br />

this mystery shopper) what does he do in his spare time?<br />

And when he says ‘Why, I read Mr Dickens’, he <strong>of</strong>fers him<br />

a ticket for the evening show. At 8 o’clock, exactly 8 o’clock,<br />

the haberdasher <strong>and</strong> the folk <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> witness the miracle<br />

<strong>of</strong> the master’s metamorphosis, the raising <strong>of</strong> the spirits<br />

he becomes, the blazing eyes, the terror in the dark, the charge,

the shuddering, the rasping then the piping voice,<br />

‘…the pool <strong>of</strong> gore that quivered <strong>and</strong> danced in the sunlight<br />

on the ceiling… such flesh <strong>and</strong> so much blood!!!’<br />

The killer <strong>and</strong> the killed. Killing himself. The more<br />

himself for being someone else. After the awestruck<br />

silence <strong>and</strong> frightened faces come the roars<br />

<strong>and</strong> cheers. A single bow before he goes back to his rooms,<br />

his dripping suit thrown <strong>of</strong>f, to walk <strong>and</strong> walk<br />

<strong>and</strong> come back down <strong>and</strong> come back to the world.<br />

He lies prostrate. His voice has gone. His temples ache.<br />

Dreams <strong>and</strong> visions. His swollen foot <strong>and</strong> rheumatism,<br />

facial pains <strong>and</strong> stomach pains torment him. Less than<br />

the memory <strong>of</strong> ghosts, his father, mother, brothers,<br />

daughter, friends... And Mary. The laudanum to make him sleep<br />

begets more dreams. Of the horse that savaged him, the dog he<br />

had to shoot, <strong>of</strong> his pet raven, Grip, that died (soon to be auctioned<br />

<strong>of</strong>f with his effects after he dies). He aches for Ellen, feels the stockings<br />

slide between his fingers, cascade away <strong>and</strong> hiss like water to the ground.<br />

15

16<br />

Carol Rumens<br />

The Gentleman for Nowhere<br />

As Nella <strong>and</strong> I walked down the Euston Road (I’d insisted we get <strong>of</strong>f<br />

the tube at Baker Street) King’s Cross Station appeared on the<br />

horizon with more than usual ominousness. The twin engine-sheds,<br />

in my opinion, embodied Victorian railway design at its functional<br />

best. But today they seemed to turn their back on London, <strong>and</strong> their<br />

glum, slumped look was disheartening. Who’d believe their claim to<br />

be a gateway to an idea as vast as the North?<br />

And was the North vast any more? I worked there now. It was my<br />

first proper job: Assistant Lecturer in Victorian Literature, Faculty<br />

<strong>of</strong> Arts, Ludology <strong>and</strong> Social Education, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>.<br />

<strong>Hull</strong> had been the last resort. I’d wanted to teach Dickens in<br />

Dickens’s city. I got as far as interviews, but my approach to literature<br />

was judged by the metropolitan grant-rakers to be insufficiently<br />

theoretical. At UCL, for instance, I was told by the muslin-bloused<br />

female chairperson that my monograph would have made an<br />

interesting contribution to Dickens studies had it been published in<br />

1912, but for 2012 it was decidedly retro. The panel had laughed<br />

merrily, <strong>and</strong> so had I. A compliment, then – but not a job-<strong>of</strong>fer.<br />

I’d come home for the holiday, still on probation. Now I was going<br />

back to Yorkshire, having learned from a headed letter from Human<br />

Resources that my contract had been renewed – it seemed,<br />

indefinitely. I shouldn’t have told Nella, but, in a moment <strong>of</strong> feeble<br />

self-congratulation, I had.<br />

We were still ridiculously early, <strong>and</strong> it was my fault, so we looked<br />

around that monstrous folly, St Pancras Station. Nella approved the<br />

idea <strong>of</strong> a cocktail in a glitzy bar, but I dissuaded her. We finally found<br />

an almost-empty bijou Costa looking out over the new concourse<br />

at King’s Cross.<br />

Ever willing to blur the absurdly trivial distinction between<br />

railway-station <strong>and</strong> airport, Network Rail had labelled this smaller<br />

folly, Departures. I called it the Phantom Limb. Shiny, inessential

shops formed a horseshoe shape under a high, branching tree <strong>of</strong><br />

slender veins which glowed at various intensities <strong>of</strong> pinkish-purple.<br />

It had cost five hundred <strong>and</strong> fifty million pounds to assemble this<br />

Olympic fantasy, this corporate c<strong>and</strong>y-floss-machine, spinning dross<br />

where the British Empire used to spin gold. The Victorian equivalent<br />

would have been the Great Exhibition. At least there was a certain<br />

mad gr<strong>and</strong>eur to complacency <strong>and</strong> self-congratulation in those days,<br />

Nella hadn’t seen the phantom limb before. While she pretended<br />

to deplore its vulgarity, she loved it. It made her feel skittish. She had<br />

even taken a picture <strong>of</strong> the sign saying Platform 9¾.<br />

‘You will look at those riverside apartments soon, won’t you?’ she<br />

coaxed as we sipped our Americanos. This was her favourite topic,<br />

her conviction that the riverside was the brightest, trendiest prospect<br />

for young marrieds in <strong>Hull</strong>, vastly preferable to the sedate Avenues,<br />

which settled older colleagues persistently recommended.<br />

Nella’s idea was fundamentally humane: it was the painless<br />

combination <strong>of</strong> our alien desires. She simply wanted a notional<br />

urban elegance – <strong>and</strong> a nice little hall for the pram. Mine, <strong>of</strong> course,<br />

was the foolish desire, the Dickensian fantasy, as she called it.<br />

But she was a br<strong>and</strong> manager, after all, <strong>and</strong> Dickens was inarguably<br />

my br<strong>and</strong>. To her credit, she understood how much He mattered, as<br />

fellow academics never understood. She knew how helpless I was in<br />

the grip <strong>of</strong> my mania, how little <strong>of</strong> the detached scholar informed<br />

my work. My devotion to Dickens was gut-brain stuff, visceral,<br />

based on childhood moral indoctrination, <strong>and</strong>, later, rivalry,<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ound <strong>and</strong> aching – my nine-year-old yearning first to be Master<br />

David Copperfield, <strong>and</strong> then to be the writer <strong>of</strong> David Copperfield.<br />

Nella knew <strong>of</strong> this last ambition, too – though she no longer took<br />

it seriously.<br />

I said I would look around, <strong>and</strong> she squeezed my h<strong>and</strong>.<br />

‘I’m told those riverside apartments reek <strong>of</strong> whale-oil,’ I added,<br />

mischievously.<br />

I’d been re-reading Mugby Junction, a collection <strong>of</strong> linked short<br />

stories by Dickens <strong>and</strong> four other writers. The eponymous hero <strong>of</strong><br />

17

18<br />

the first tale, Barbox Brothers, gets <strong>of</strong>f the train at a stop before his<br />

destination. W<strong>and</strong>ering round the deserted station, he meets Lamps,<br />

whose job is to clean the many station lights. The little room where<br />

his noble toil is based smells, Dickens says, like the cabin <strong>of</strong> a whaler.<br />

I’m still investigating whether he refers to whaling anywhere else.<br />

The analogy between Lamps’s oily room <strong>and</strong> the whaler has been a<br />

comfort to me from the instant I’d thought about applying to <strong>Hull</strong>.<br />

Nella’s too-small blue eyes had become cold, <strong>and</strong> I saw the edges<br />

<strong>of</strong> her smile droop. Then, as the smile-muscles bravely hitched up<br />

that tiny but immense weight <strong>of</strong> disappointment, I imagined I could<br />

smell air-freshener. The perfume was somehow the colour <strong>of</strong> the<br />

lights above our heads – a lilac, rose, hyacinth, violet chemical<br />

cloud possessing that spacious, airy pent-house overlooking the<br />

bloodless water.<br />

She kissed me goodbye without a tear, in fact with a joke about<br />

academic wars <strong>and</strong> brave soldiers. She choreographed our pose to<br />

resemble the giant bronze study <strong>of</strong> embracing lovers in St Pancras –<br />

she could do these ironical things sometimes, <strong>and</strong> I appreciated it.<br />

My war – my work – was no threat. She would have her flat, her air<br />

freshener <strong>and</strong> her faux oil-lamps, <strong>and</strong> then, in less than a year’s time,<br />

she would have ‘our’ baby, <strong>and</strong> so complete the process <strong>of</strong> weaning<br />

me from Dickensian to drab.<br />

With that unhappy thought in mind, I approached the ticket barrier.<br />

I still had twenty minutes till my train. An over-helpful guard,<br />

evidently a graduate <strong>of</strong> an Olympic Games Customer Service<br />

Initiative, twitched open the disabled access gate.<br />

‘There’s nothing the other side,’ he warned, having glimpsed my<br />

ticket, <strong>and</strong> showing he was magnanimously prepared to let me exit<br />

in the gr<strong>and</strong> manner with which I’d entered.<br />

I ignored him <strong>and</strong> went into the grimy, darkened shell that had<br />

been the main concourse. Nothing was what I wanted. I remembered<br />

when enormous docile queues would wind themselves several times<br />

around the hall, inching towards invisibly distant trains to

Newcastle, York, Edinburgh <strong>and</strong>, no doubt, <strong>Hull</strong>. I’d tack myself onto<br />

a queue with a combination <strong>of</strong> deep reluctance <strong>and</strong> deep resignation<br />

that I supposed made me a truly British citizen. My trips in those<br />

days were driven by my pursuit <strong>of</strong> novelistic material, ‘seeing the<br />

world’ as I thought <strong>of</strong> it. Later on, I was a bright, over-aged PhD<br />

student at Goldsmith’s, eager to give careful little papers on Dickens<br />

<strong>and</strong> Premonition, or Dickens <strong>and</strong> Alcohol, in cities I knew He<br />

had visited.<br />

The last Flying Scotsman had left a decade before I was born, but<br />

there was still a certain atmosphere about the station, a lingering<br />

moodiness <strong>of</strong> steam. I walked carefully among the shades <strong>and</strong><br />

shadows. Underfoot, the brown-grey, semi-shiny stone resembled<br />

skin, strangely dimpled in places, patched here <strong>and</strong> darned there. A<br />

rich smell <strong>of</strong> old waiting-rooms drifted over me, <strong>of</strong> damp, s<strong>of</strong>t<br />

wooden floors, impregnated with dirt. I tasted smoke. And then I<br />

saw Him, at the end <strong>of</strong> the platform, a darting human genie made<br />

<strong>of</strong> fire <strong>and</strong> mist, surrounded by a fiery-misty crowd <strong>of</strong> fellow-actors,<br />

including pretty teenaged Ellen <strong>and</strong> her sly mama, their mass <strong>of</strong> bags<br />

in the care <strong>of</strong> fiery-misty, cap-d<strong>of</strong>fing porters. He shouted orders<br />

<strong>and</strong> jokes, he hurried everyone along, he blew kisses to Catherine,<br />

the donkey-wife he was already leaving behind.<br />

My elation died as the Pendolino nosed in. The Pendolino is a<br />

moulded-plastic Disneyl<strong>and</strong>, nursery-school, health-<strong>and</strong>-safety<br />

train, a pretend airplane-train, a train that can’t sing, even when it<br />

manages to reach forty miles per hour, a train whose wheels never<br />

go der-der-der-dum over the rails, a train which, when it stops<br />

precariously in the middle <strong>of</strong> a viaduct, has no furious steam to gush<br />

forth, not even any batteries to re-charge with a reassuring, patienthorse<br />

whinny: a train gloss-coated <strong>and</strong> uneventful as a banker’s<br />

conscience. And here it was, trying to look important.<br />

I queued briefly to get into the Quiet Coach. The backs <strong>of</strong> the seats<br />

had great orange ears sticking out, like some cartoon elephant’s. I<br />

hadn’t made a reservation. Apparently, no-one had. The little<br />

information-screens overhead were innocent <strong>of</strong> information. I sat<br />

19

20<br />

down in an aisle seat in the middle <strong>of</strong> the coach, away from the<br />

ungenerous luggage racks, focus <strong>of</strong> a panicky scrum at every station,<br />

<strong>and</strong> away from the horrible unventilated toilets, which tainted the<br />

local environment with stale nappy-smell, <strong>and</strong> made noises like an<br />

old tea-urn whenever their pumps delivered minutely-measured<br />

two-second squirts <strong>of</strong> water <strong>and</strong> hot air.<br />

The airline-style seats were the only thing I liked about the<br />

Pendolino. I thought <strong>of</strong> them as autism seats – high functioning<br />

autism, <strong>of</strong> course, for those who could cope with the world provided<br />

they didn’t have to strike up conversations with it. Facing a chairback<br />

in such a cramped space was curiously reassuring, provided<br />

the inside seat remained unoccupied.<br />

I switched <strong>of</strong>f my phone, obedient to the Quiet signs on the<br />

windows. No-one joined me. I opened my ragged, much annotated<br />

paperback copy <strong>of</strong> Mugby Junction, then closed it. I didn’t want to<br />

think about Barbox. When he gets out <strong>of</strong> the train, he doesn’t know<br />

where he is or where he’ll go. Mugby Junction is his mysterious<br />

portal to transformation. Whereas I know all the stations, cities <strong>and</strong><br />

towns en route to <strong>Hull</strong>: I could get out at any one <strong>of</strong> them <strong>and</strong> not<br />

abolish my past or discover my future. Tracy-our-train-manager was<br />

announcing them now, each one, from Milton Keynes to Brough, a<br />

hammer-blow to the imagination.<br />

The train moved <strong>of</strong>f at last, <strong>and</strong> I craned over to my sliver <strong>of</strong><br />

window, ravenously hungry for old brick houses, out-buildings <strong>and</strong><br />

redundant iron ladders, pulleys <strong>and</strong> pipes, desolate ancient wagons<br />

<strong>and</strong> rusting rails. And I felt a tremendous pang, almost sob-like, <strong>and</strong><br />

the repressed thought swelled up chokingly: London, London, I’m<br />

leaving you, I’m leaving Him.

No, not so. He had given recitations in <strong>Hull</strong>. He’d been there three<br />

times, in fact: all in the autumn <strong>of</strong> 1858. The first occasion was on<br />

September 14th. The next two performances were on consecutive<br />

evenings, the 26th <strong>and</strong> 27th <strong>of</strong> October, when he stayed at the Royal<br />

Station Hotel. Both times he had been on tour, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> wasn’t much<br />

more than a dot on his itinerary. It seems that he’d travelled down<br />

from Scarborough for the first reading, <strong>and</strong> had returned to the<br />

Royal Hotel in the seaside town the same night. The next time he<br />

had travelled to <strong>Hull</strong> from York, <strong>and</strong> then gone on to Leeds.<br />

His performances had taken place in the Assembly Rooms,<br />

Kingston Square, now, the New Theatre. What consolation there is<br />

in those pale Ionian pillars, like a section from the façade <strong>of</strong><br />

Buckingham Palace, still exactly as he’d seen them in 1858! The<br />

theatre’s Victorian interior had been stripped in the 1920s. But you<br />

could still sense an atmosphere, a tingling <strong>of</strong> the sensations. The<br />

Assembly Hall audience was not inhibited. Among the wealthy <strong>and</strong><br />

protected were men <strong>and</strong> women whose rough, river-side <strong>and</strong> seagoing<br />

trades stained their h<strong>and</strong>s with life <strong>and</strong> death. They still<br />

shuddered, laughed, wept in the fine traces <strong>of</strong> Victorian dust.<br />

I knew exactly the kind <strong>of</strong> figure He made on stage, a thin, intense,<br />

fierce-eyed, elegant figure but a short one in stature, a speciallydesigned<br />

low reading-table in front <strong>of</strong> him. The table was covered<br />

21

22<br />

with baize: green baize, he favoured at first, but later on he had it<br />

refitted, <strong>and</strong> the new cloth was a startling blood-red. Behind him<br />

hung a sheet-like screen, intended to help project his voice into the<br />

audience, but which must have had a magic lantern effect, his<br />

movements repeating in a shadow play behind him. This would have<br />

contributed eerily to his more Gothic performances. His lighting<br />

was provided by two 12-feet high gas-pipes. A gas-man <strong>and</strong> other<br />

roadies came along with the equipment, while he travelled in firstclass<br />

Pullman. He was like a celebrity on tour – an analogy I’d tried<br />

to impress on the students, asking them who their favourite popgroups<br />

were. Their friendly answers confused me. I didn’t know any<br />

<strong>of</strong> the names. If their imaginations had been fired by my<br />

comparison, I couldn’t smell the burning.<br />

In the last five years <strong>of</strong> his life, when the big reading-tours took<br />

place, Dickens hated trains. The Staplehurst accident had nearly<br />

killed him. Some rails across a 42-foot drop had been removed for<br />

maintenance-work, <strong>and</strong> hadn’t been replaced. The foreman<br />

consulted the wrong time-table. He thought the train from Dover,<br />

Dickens’s train, wasn’t due for another two hours.<br />

Dickens’s coach hung suspended over the River Beult, saved by<br />

the coupling which attached it to the second-class coach behind.<br />

Ellen, Mrs Ternan <strong>and</strong> he linked h<strong>and</strong>s so that, in Ellen’s words, they<br />

would die friends. Once freed, he went among the wounded <strong>and</strong><br />

dying with his br<strong>and</strong>y-flask <strong>and</strong> a top-hat filled with river water. He<br />

couldn’t bear to look at some <strong>of</strong> the injuries.<br />

He was never again sure <strong>of</strong> the iron monsters he depended on.<br />

He’d take a long gulp from the flask at the start <strong>of</strong> each trip, but<br />

sooner or later he began to sweat, <strong>and</strong> to count out the passing<br />

stations. Serialised horror! Sometimes, he jumped out at an earlier<br />

station <strong>and</strong> tramped the last miles. It was quite likely he’d walked<br />

from an intermediate station the day he went to <strong>Hull</strong> from<br />

Scarborough – Beverley, perhaps, or Cottingham. I was going to try<br />

it for myself one day.<br />

I trawled around the documents on my laptop, entering the

forbidden regions where I still deluded myself I was a novelist. A<br />

man got on at Crewe, irritatingly occupied the aisle seat across from<br />

me <strong>and</strong> tried to start a conversation. I ignored him. I’d scrolled up<br />

my sketches <strong>of</strong> Gaby <strong>and</strong> Angela, the novel’s love interest. They were<br />

flaccid characters, I feared, although drawn from so-called real life.<br />

Gaby was based on Aimee, a student from some local housing estate,<br />

ditzy <strong>and</strong> tiny in black tights, a flared miniskirt <strong>and</strong> those useless<br />

little fur-topped boots the <strong>Hull</strong> girls were wearing. Angela was<br />

Laura, a mature student, keen in a vague, placid sort <strong>of</strong> way. She was<br />

unhappily married in my story, <strong>and</strong> my protagonist was going to<br />

have an affair with her, if his author could muster the required<br />

energy. I gave her some perfectly constructed sentences, but the idea<br />

<strong>of</strong> her didn’t excite me.<br />

I was bored <strong>and</strong> my calves ached. Blood-clots formed in my veins<br />

like points failures. I got up, stretched <strong>and</strong> took a walk down the<br />

orange plastic coach. It became steadily dimmer <strong>and</strong> narrower, lit<br />

only by faintly gleaming wood. I was st<strong>and</strong>ing in the corridor<br />

outside the saloon where He <strong>and</strong> his male companions had a great<br />

table to themselves, lit with pink-shaded oil-lamps. The men were<br />

playing cards. He wasn’t playing: he was in the corner, cushioned,<br />

asleep. He rolled from side to side with the train <strong>and</strong> I thought I<br />

could hear him groaning.<br />

I gathered my courage, slid open the door, <strong>and</strong> went in. No-one<br />

noticed. I saw his eyelids were those <strong>of</strong> an old man, thin <strong>and</strong><br />

purplish. I pushed through into his dream.<br />

It was a small miserable room with a table <strong>and</strong> chairs, a bedcurtain,<br />

<strong>and</strong> a shelf <strong>of</strong> liquor bottles. Of human occupation I could<br />

see only an arm stretched back, a h<strong>and</strong> gripping what looked like<br />

the stave from a broken cask, <strong>and</strong> a woman’s curly hair, like a wig<br />

thrown onto the tiled floor. It was His arm, I knew from the shirtcuff,<br />

the sham wedding-ring. I felt a sensation like the beginning <strong>of</strong><br />

a big wave or a gust <strong>of</strong> wind, some natural force, full <strong>of</strong> exuberance<br />

<strong>and</strong> heartlessness. It gathered in me with a silent roar, <strong>and</strong> I felt his<br />

joy as he brought the stave down into the mass <strong>of</strong> curling hair.<br />

23

24<br />

The shirt-cuff instantly turned from white to wringing-wet<br />

crimson. I heard a chorus <strong>of</strong> screams, <strong>and</strong> saw lolling, bloody heads<br />

<strong>and</strong> faces, among them the white moulded-looking features which<br />

I knew were those <strong>of</strong> the woman whose skull had been smashed with<br />

such joy. As this hellish vision faded, I saw the card-players were still<br />

engrossed. The sleeper had opened his eyes, <strong>and</strong> was staring, in<br />

glassy terror, at the scene I’d just left.<br />

I leaned over <strong>and</strong> touched His shoulder, noticing the dark cloth<br />

<strong>of</strong> the sleeve <strong>and</strong> the whiteness <strong>of</strong> the shirt-cuff. He felt my touch,<br />

shuddered, looked at me. The train slowed into the shadows <strong>of</strong><br />

a station.<br />

‘Get <strong>of</strong>f here,’ I said, ‘I’ll drive you. I’ve a cab waiting. It will take<br />

no more than an hour longer, <strong>and</strong> you’re not short <strong>of</strong> time.’<br />

My voice sounded very young <strong>and</strong> uncertain in pitch. I’d become<br />

a boy <strong>of</strong> 14 or 15. My h<strong>and</strong>s were sweating.<br />

‘Please, trust me. I’ve read all your dreams. And I’m a writer, too.’<br />

He stared at me with a strange, cold expression.<br />

‘If you can read my dreams, perhaps you ought to be.’<br />

His words thrilled me. I began stuttering but he interrupted.<br />

‘I like killing her. Of course I do. You can surely underst<strong>and</strong> that?’<br />

I whispered yes, <strong>and</strong> he smiled. His movements were slow <strong>and</strong><br />

stiff, but I know he intended to get up <strong>and</strong> follow me.<br />

My body jerked with a sweet sensation near orgasm. It vanished<br />

quickly <strong>and</strong> I found I was in my seat, looking up into a lean <strong>and</strong> wellmade-up<br />

young female face.<br />

She was staring back at me. ‘All tickets <strong>and</strong> rail-passes please,’ she<br />

repeated in a loud Yorkshire voice. ‘Are you intending to go all<br />

the way?’<br />

‘Yes. No. I don’t know,’ I said stupidly.<br />

She waited for me to fumble out my ticket. ‘Change at Bartonbyle-Wold<br />

for ᾽Ull,’ she said, h<strong>and</strong>ing it back.<br />

‘I thought this was the direct train.’ This was the man sitting across<br />

the aisle from me. He looked about 70, <strong>and</strong> seemed dressed for a<br />

walking-tour rather than a business appointment, but he sounded

highly indignant.<br />

‘There’s been an incident <strong>and</strong> we’re not going all the way now.<br />

Change for ᾽Ull at Bartonby-le-Wold, <strong>and</strong> remain on the platform.’<br />

I wiped my palms furtively on my trouser-knees.<br />

‘What sort <strong>of</strong> an incident?’ I asked, dreading the reply.<br />

‘Protestors or rioters or sommat, chucking girders on t’line. Plain<br />

v<strong>and</strong>alism, in’t it?’ Tracy-the-train-manager walked away, with a<br />

gleam-catching movement <strong>of</strong> her pony-tail.<br />

The old fool was excited. ‘Protesting about what?’ he shouted, but<br />

Tracy strode resolutely on.<br />

‘I used to be a protestor! CND. We used to march to Aldermaston,<br />

I remember…’<br />

I put my finger to my lips as another voice, the driver’s, perhaps,<br />

came over the intercom. It was the same announcement, though<br />

garbled <strong>and</strong> choked by poor amplification.<br />

I’d never heard <strong>of</strong> Bartonby-le-Wold. It sounded remote in time<br />

<strong>and</strong> place. How far from <strong>Hull</strong> it was I didn’t know; but it was far<br />

enough. I’d need to make certain phone calls, tell certain white lies,<br />

but it could be done. My heart raced. I zipped up the laptop, packed<br />

away Mugby <strong>and</strong> my unread newspapers.<br />

I saw myself arriving at the tiny rural station. Instead <strong>of</strong> staying<br />

on the platform in the jostle <strong>of</strong> disgruntled passengers, I walked<br />

resolutely away <strong>and</strong> turned down the little approach-road, hearing<br />

birdsong, staring around me <strong>and</strong> storing everything I saw, as I had<br />

in the days when I meant to write David Copperfield, in the days<br />

when I went all over the British Isles because I needed material,<br />

needed to see the world.<br />

I smiled to myself. Not the world, but the wold. A peaceful place,<br />

a room in an old pub, the kind Nella would call Dickensian, <strong>and</strong><br />

time stretching around me like the unassuming countryside.<br />

It wasn’t too late. Nella planned to fall pregnant soon, but I was<br />

pregnant already. My infant was only a few chapters long, cradled<br />

in a rarely-updated Office Word document, but it was going to live<br />

<strong>and</strong> grow, now that He trusted me. I could read His dreams. I ought<br />

25

26<br />

to be a writer, if I could read his dreams.<br />

The train crawled slower <strong>and</strong> slower until it stopped. Weed-hung<br />

embankments rose on either side. It was impossible to see where we<br />

were. How far was Bartonby, I wondered impatiently. Even the old<br />

man didn’t know. He didn’t believe the announcements, anyway,<br />

they were all idiots on Humber Trains. He was pretty sure Beeching<br />

had shut down Bartonby in the sixties. Perhaps we were waiting for<br />

some ancient stretch <strong>of</strong> rail to be weeded, oiled <strong>and</strong> otherwise made<br />

safe, he joked. Oh come on, come on, I thought. My resolve wouldn’t<br />

last for ever.<br />

After an incalculable rest-period, the train decided to crawl<br />

gingerly onwards again <strong>and</strong> Tracy’s voice came triumphant over<br />

the intercom.<br />

‘Humber Trains are pleased to inform passengers that the<br />

obstruction to the track has now been cleared, <strong>and</strong> we will NOT<br />

making an unscheduled stop at Bartonby-le-Wold. We will be<br />

arriving at Doncaster in approximately seventeen minutes.<br />

We apologise for the late running <strong>of</strong> this service <strong>and</strong> any<br />

inconvenience it may have caused to your onward journey.’<br />

The old fool across the aisle from me applauded in a frenzy <strong>of</strong><br />

satirical glee. ‘Any inconvenience, any inconvenience!’ he shouted.<br />

‘Any inconvenience it just may have caused? Any inconvenience it<br />

just may have caused to my onward journey? My onward journey is<br />

an abstraction, it can’t suffer from inconvenience. Whereas I most<br />

definitely can, <strong>and</strong> do!’<br />

Once again, I hushed him. I listened hard as the message was<br />

repeated. In a moment, my pulse-rate returned to normal, my hope<br />

evaporated.<br />

An hour <strong>and</strong> a half later, the last false apology had been uttered,<br />

<strong>and</strong> we were in Paragon Station, <strong>Hull</strong>. I headed across the forecourt<br />

towards the back entrance <strong>of</strong> the hotel. It was where I always stayed.<br />

I have never let on to Nella, because we’re supposed to be saving for<br />

the darling riverside flat. I told her I stayed in the university lodgings<br />

in Tunny-Fish Grove.

I felt shaky, as if I’d just sat an exam <strong>and</strong> knew I’d failed. The rather<br />

ethereal bronze <strong>of</strong> Larkin’s statue met me mid-run; he was, as usual,<br />

late getting away. But getting away he was. His image cheered me<br />

up, a little.<br />

As I walked across the great barn <strong>of</strong> the hotel bar towards<br />

Reception, I heard my name. I turned, <strong>and</strong> there, shipwrecked but<br />

surfacing from a deep oxblood s<strong>of</strong>a, were my student-prototypes <strong>of</strong><br />

Gaby <strong>and</strong> Angela, waving with exaggerated, <strong>and</strong>, it seemed, ironical<br />

gestures. I raised my h<strong>and</strong> to them vaguely, <strong>and</strong> proceeded to the<br />

desk. As I waited to get the clerk’s attention, Aimee came to my side.<br />

‘I wasn’t sure if you saw who it was. You know, us,’ she said, a bit<br />

breathless. ‘You’d be welcome to have a drink with us, Chris, if you’re<br />

not too busy or nothing.’<br />

She grinned at me boldly. Chris. I always insisted my students call<br />

me Dr. Stretton. Her short black ringlets danced. Her eyes were<br />

dilated with alcohol – or perhaps some other vicious substance<br />

popular with her strangely self-abusive generation.<br />

I told her I was going to be busy, <strong>and</strong> asked if she’d started reading<br />

David Copperfield yet.<br />

She wrinkled her nose. ‘Don’t ask. I’m really trying. Some <strong>of</strong> it’s<br />

dead wordy.’<br />

‘You’re right. It is. I’ve decided to change the set text to Oliver<br />

Twist.’<br />

She seemed unaffected by my news.<br />

‘Haven’t you ever seen it serialised on TV? Or Oliver – the<br />

musical?’<br />

She shook her head, mystified. I ploughed on.<br />

‘It’s a shorter book, very dramatic. Lots <strong>of</strong> issues to discuss. You’ll<br />

like it. But <strong>of</strong> course you do need to persevere with Dickens. He<br />

wrote for readers with a long attention-span. The attention-span is<br />

rather like a muscle. Exercise it <strong>and</strong> it will get bigger <strong>and</strong> harder.’<br />

Aimee brought her h<strong>and</strong> to her mouth. There was a shiny metal<br />

ring on every finger. Bling, I think it’s called. She shook with<br />

suppressed laughter.<br />

27

28<br />

‘Good evening Dr Stretton, how are you tonight?’ The young clerk<br />

came over at last <strong>and</strong> h<strong>and</strong>ed me my key. He winked at me. ‘The<br />

Charles Dickens Suite, as usual.’<br />

Aimee stopped gasping for breath beside me. She uncovered her<br />

mouth.<br />

‘Is this where Charles Dickens lives?’<br />

‘Dickens died in 1870, Aimee.’<br />

‘I mean, like, in the olden days?’<br />

She had blushed prettily through her make-up. Her bling sparkled.<br />

Her eyes were lustrously wet <strong>and</strong> wide.<br />

‘No. He stayed at the Royal Station Hotel on a visit. I’ve got his<br />

old room.’<br />

‘You’re kidding! Can I come <strong>and</strong> see it?’<br />

‘It’s nothing special. But if you’re interested in places associated<br />

with Dickens, I can show you a wonderful spot.’ I took a deep breath<br />

as I risked the name – for all I knew, her family might have raised<br />

sheep or cauliflowers there for generations.<br />

‘Bartonby-le-Werld,’ she echoed, dubiously. ‘Is that in France?’<br />

‘No, but it’s a glorious little place. It was where Dickens’s other<br />

girl-friend lived. Not Ellen Ternan. Another one, originally from<br />

<strong>Hull</strong>. A girl no-one knows much about – well, except me, <strong>and</strong> now<br />

you. There’s a lovely Victorian pub there – it’s the pub where they<br />

used to meet. We could have lunch outside, if it’s sunny. It’s not far<br />

– I can drive you. Let’s exchange numbers.’<br />

‘Mint!’ Her eyes shone at me. But the other eyes, behind hers,<br />

seemed to form sharp points <strong>of</strong> ice. They had a dazzle which hurt<br />

me. He was challenging me. I didn’t know the nature <strong>of</strong> the<br />

challenge, but I would find out. I stayed calm, kept my voice <strong>and</strong><br />

focus steady.<br />

‘I’ll give you a ring early tomorrow, Aimee.’ Briefly, I touched her<br />

hair, feeling the shine <strong>and</strong> s<strong>of</strong>tness <strong>and</strong> depth, feeling the idea <strong>of</strong> the<br />

North <strong>and</strong> its infinite vastness. She was happy with that, <strong>and</strong> so<br />

was He.

Image: Malcolm Watson<br />

29

30<br />

Aingeal Clare<br />

The Man <strong>and</strong> the Peregrine <strong>and</strong> the Chimney<br />

There once was a man who lived in the chimney <strong>of</strong> a great empty<br />

factory. At night he could be heard singing the melancholy songs <strong>of</strong><br />

his youth.<br />

On the very top <strong>of</strong> the chimney nested a peregrine falcon, in an<br />

acute state <strong>of</strong> fertility. No-one knew exactly the number <strong>of</strong> chicks it<br />

had reared, but it was a great many. During the day, the bird could<br />

be seen circling dramatically above the tower; but it was never seen<br />

to hunt, for this was an activity reserved for darkness.<br />

Sleepless children who preferred their windows open at night were<br />

intimate with the man’s songs, as were the streetwalkers <strong>of</strong> Dagger<br />

Lane <strong>and</strong> the dockside nightwatchmen. The drunks who made beds<br />

<strong>of</strong> wire benches knew him, as did the hacks <strong>and</strong> editors whose<br />

periodicals were soon to go to press, <strong>and</strong> who had stepped out onto<br />

balconies to light a late night cigarette <strong>and</strong> think.<br />

In his songs, the man <strong>of</strong>ten referenced his friendship with the peregrine.<br />

Hidden somewhere in the vast <strong>and</strong> unruly <strong>and</strong> sometimes desolate<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>of</strong> each ballad was the bird’s secret name, <strong>and</strong> it was a kind <strong>of</strong><br />

game to find it. Listeners had discovered the bird tucked inside an old<br />

oak tree, where two lovers now parted had once pleased to meet;<br />

quarrelling with a farmyard cat, while in the barn a duel was being<br />

fought; drifting near the core <strong>of</strong> some dark cloud, whose rumblings<br />

betokened a ruined harvest; <strong>and</strong> reflected in a young woman’s iris as<br />

she st<strong>and</strong>s alone at the edge <strong>of</strong> a lagoon, aware she has been poisoned<br />

by her jealous cousin <strong>and</strong> will die (these are the songs the man sang).<br />

If the peregrine was not present in name or body, her eggs would<br />

be: in baskets dropped by frail girls or hurled by urchins at funeral<br />

carriages; in tainted omelettes <strong>and</strong> in foxes’ jaws.

‘What if the peregrine’s nest on the factory chimney is just another<br />

hiding place within a bigger song?’ an editor who thought himself<br />

very clever remarked to a hack as they stood smoking on the balcony<br />

after a hard night’s pro<strong>of</strong>reading.<br />

Terrific beauty <strong>and</strong> depth were in his songs, but the most curious<br />

thing about them were these puzzles all who listened learned to<br />

solve. The quickest solutions were found by children woken from<br />

nightmares, who listened at bedroom windows in stiff poses,<br />

because their concentration was the keenest.<br />

Insomniacs were in love with the man, especially during power cuts.<br />

Then one day, the peregrine left the chimney, never to return. Her<br />

name gradually faded from the man’s songs. It was sadder than all<br />

his saddest songs taken together.<br />

By <strong>and</strong> by, another name replaced the peregrine’s, around the time<br />

one <strong>of</strong> her grown chicks took to roosting on the chimney grate.<br />

Many months passed before the first child discovered what this new<br />

name was. The hacks, as usual, were the last to catch on.<br />

The streetwalkers <strong>of</strong> Dagger Lane were the most moved by this<br />

development, who grieved <strong>and</strong> rejoiced all at once, almost frenziedly,<br />

reminded <strong>of</strong> their own lost children, their own lost mothers.<br />

Inside the mouth <strong>of</strong> the factory still crouched its old organs: giant<br />

mangles, looms, <strong>and</strong> saws. These were the fossils <strong>of</strong> industry, the<br />

terrible works. Hunched on the banks <strong>of</strong> a mud canal, the factory,<br />

though menacing to most, was not without charm to this one art<br />

student whose expensive camera swung always at her hip. But even<br />

she ran away when she saw the machines.<br />

Perhaps the man was a ghost?<br />

31

32<br />

Cliff Forshaw<br />

A Trinity <strong>of</strong> Genomic Portraits for Charles Darwin<br />

Marc Quinn’s ‘genomic portrait’ (2001) <strong>of</strong> Sir John Sulston, a key figure in the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> the analysis <strong>of</strong> DNA <strong>and</strong> the definition <strong>of</strong> the human genome,<br />

consists <strong>of</strong> the geneticist’s DNA encased in a frame which mirrors the observer.<br />

Here 23 couplets represent the 23 pairs <strong>of</strong> human chromosomes.<br />

1. In the Name <strong>of</strong> the Father<br />

This kind <strong>of</strong> portrait’s just your name<br />

with DNA in a metal frame.<br />

You look into the glass <strong>and</strong> see<br />

reflected back, both you <strong>and</strong> me.<br />

Long molecules <strong>of</strong> the human race<br />

hold mirrors up to the voyeur’s face.<br />

From Genesis, here’s Revelation:<br />

Creation’s mostly Information.<br />

Magnified, they’re twisted crosses:<br />

X marks the spots <strong>of</strong> gains <strong>and</strong> losses.<br />

Each gene projects just what it means<br />

upon the human plasma screens.<br />

State-<strong>of</strong>-the-art, sharp resolution<br />

in byte-sized, digital Evolution.<br />

Conceptually, now re-creation’s<br />

a pigment <strong>of</strong> the imagination.<br />

Skin-deep, cosmetic − paint betrays<br />

the made-up thing that it portrays.<br />

The stuff that paints eyes brown or blue’s<br />

no medium for catching you.<br />

The family portrait’s now replaced:<br />

ID’s conceived to be defaced.<br />

Your skin’s tattooed, your hair is dyed,<br />

both painting <strong>and</strong> the camera lied.

Your nose is trimmed, your breasts augmented,<br />

your eyes in contacts look demented.<br />

With sculpted cheeks <strong>and</strong> capped white teeth,<br />

God only knows what lies beneath.<br />

Not just the skull beneath the skin,<br />

we want to see what’s deep within.<br />

We want to see what’s really dark<br />

− survival earned through each black mark.<br />

Now, paint-by-numbers DNA<br />

with radioactive markers, say,<br />

might, as the Geiger ticked away,<br />

catch your half-life, hint at decay.<br />

This is the sequence marked down through time<br />

− those narcissistic couplets rhyme.<br />

But duplication’s not so great:<br />

the verses limp, the genes mutate.<br />

Like chromosomes, your tiny doubles,<br />

each wriggling pair now looks for trouble.<br />

Each chromosome’s a mirrored X,<br />

which, naturally, goes wrong with sex.<br />

Y is one at such a loss:<br />

three-legged beast, or broken cross?<br />

2. The Son<br />

X kisses X, or does it lie?<br />

Twenty-two times, then maybe Y.<br />

This snapshot <strong>of</strong> your DNA<br />